A Dual-Axis Framework for Social Innovation: Mapping Dynamic Transitions Through 121 Social Businesses in Developing Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Defining Social Innovation

2.2. Social Business and Its Relationship with Social Innovation

2.3. Contextual Factors in Developing Countries

2.4. Proposing a Dual-Axis Framework for Social Innovation Typology

2.4.1. Pathway of Institutional Change: Peripheral–Integrated–Embedded

Peripheral Pathway of Institutional Change

Integrated Pathway of Institutional Change

Embedded Pathway of Institutional Change

2.4.2. Level of Innovation: User–Service–System

User-Level

Service-Level

System-Level

2.4.3. A Dual-Axis Framework for Social Innovation Typology

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Case Selection and Data Collection

3.3. Variable Definitions

3.4. Operationalization and Coding

3.5. Coding Criteria Examples

3.5.1. Pathway of Institutional Change

3.5.2. Level of Innovation

3.6. Hypothesis Development

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

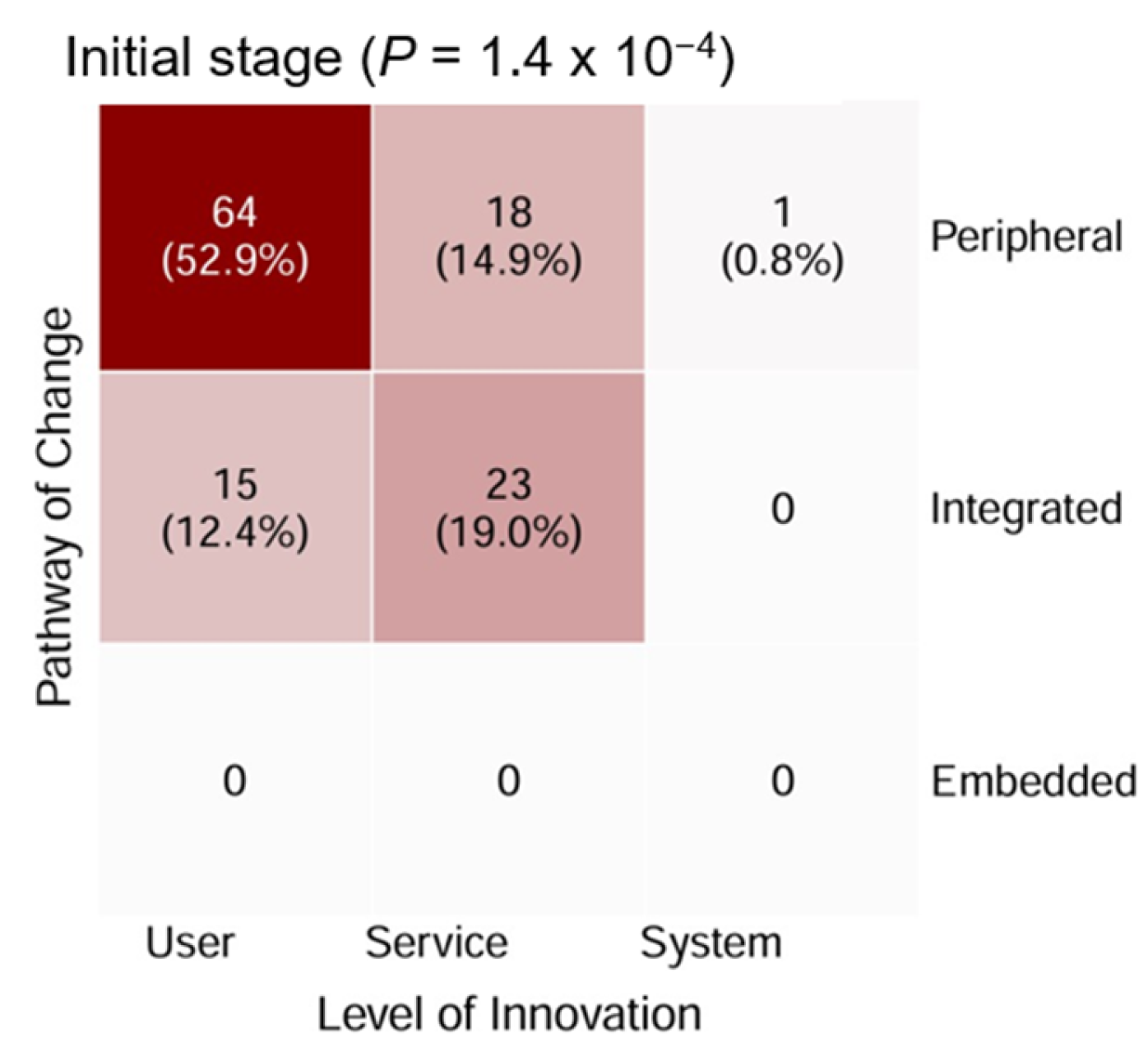

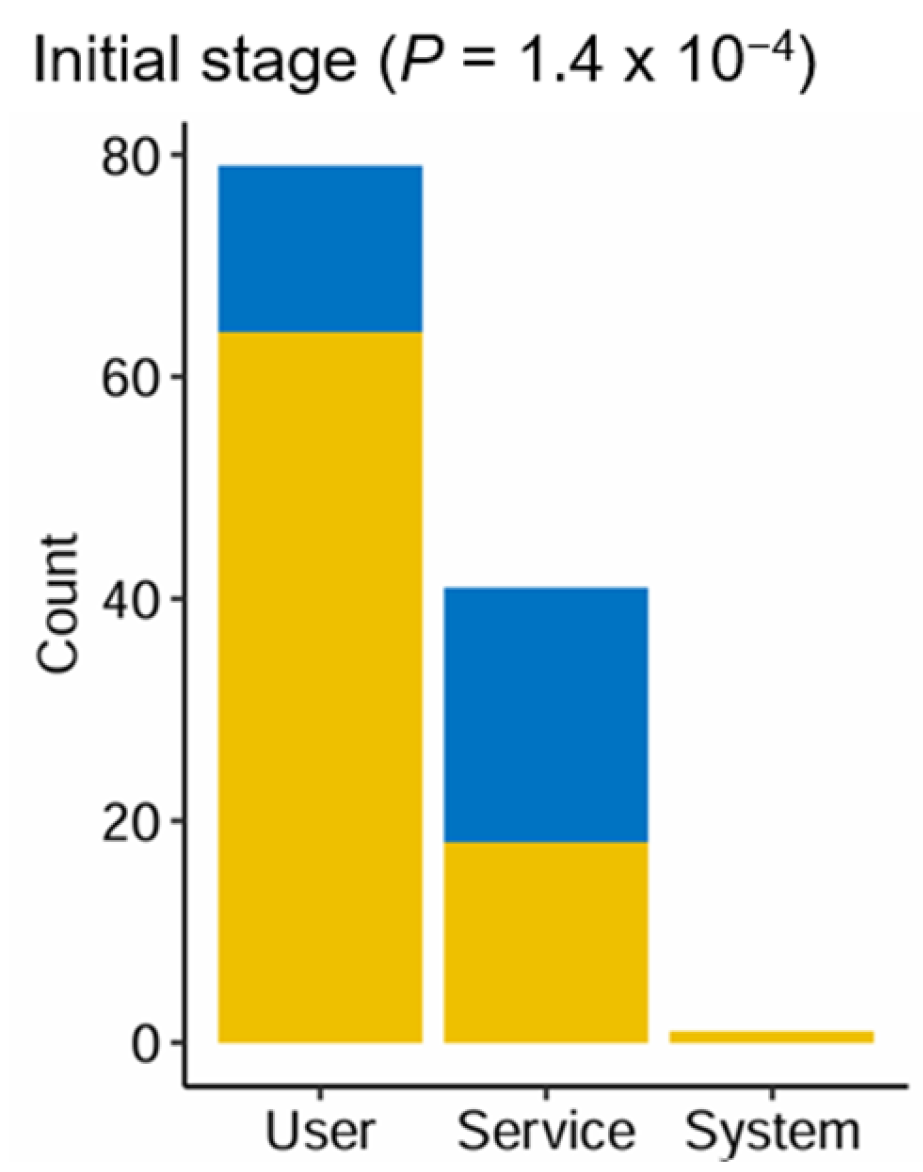

4.1. H1—Initial Distribution of Innovation Types

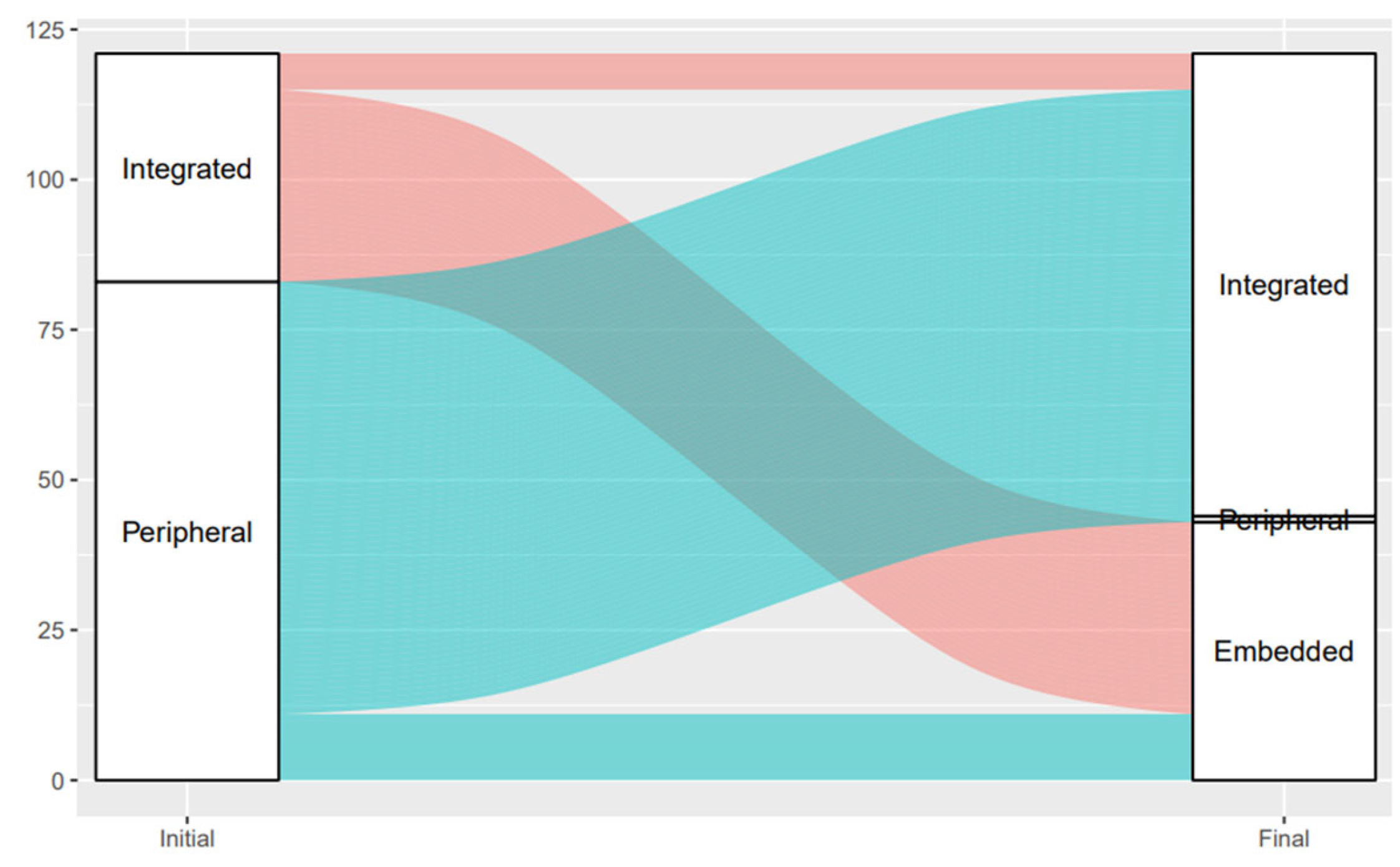

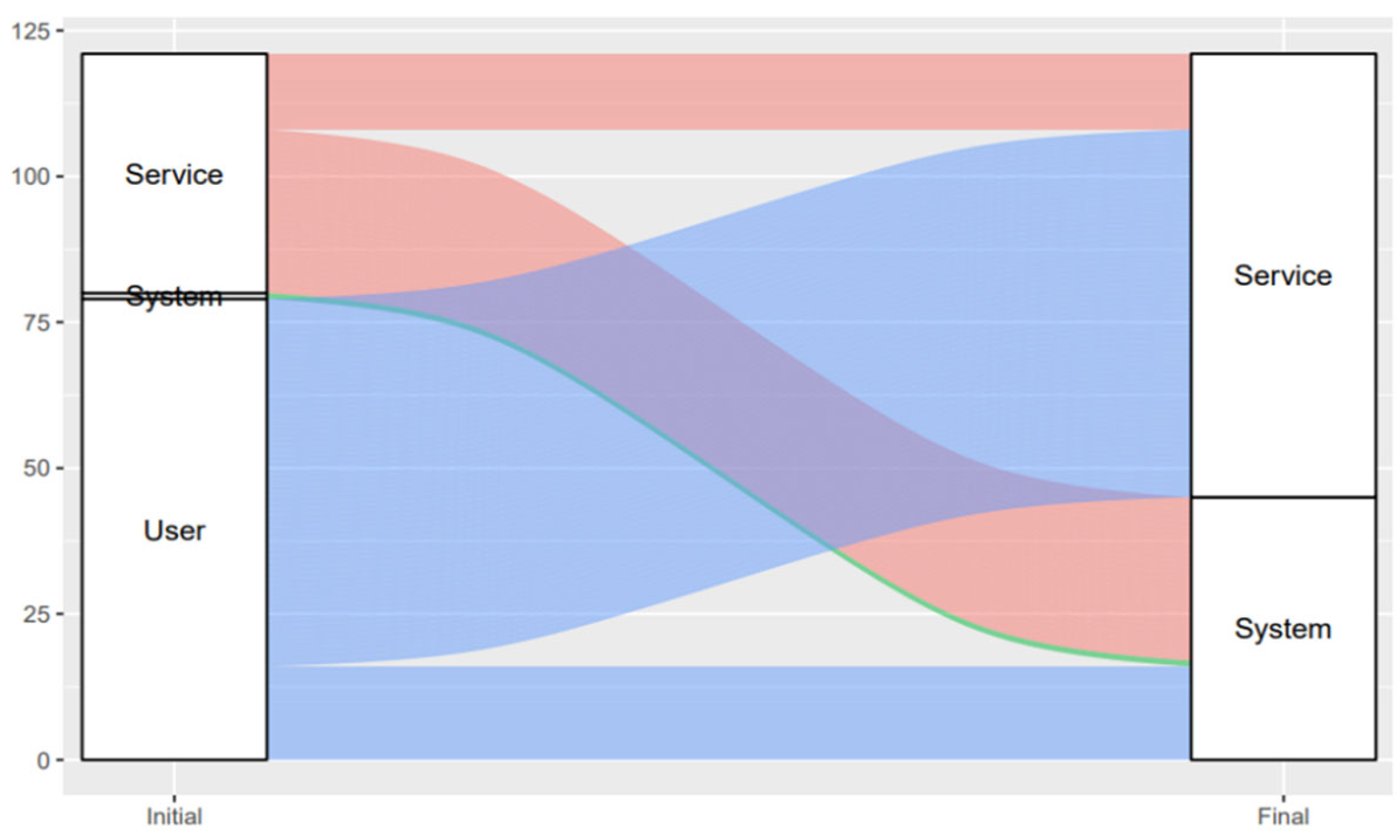

4.2. H2a & H2b—Upward Transitions in Pathway and Level

4.3. RQ3—Dominant Transition Patterns

4.4. Summary of Key Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Overview of Key Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.2.1. Social Innovation Dynamics

5.2.2. Institutional Embeddedness

5.2.3. Role of Context in Developing Countries

5.3. Practical and Policy Implications

5.4. Critical Reflections and Limitations

5.4.1. Path Dependency and Structural Constraints

5.4.2. Survivorship Bias

5.4.3. Limitation of Secondary Data Dependence and Data Bias

5.4.4. Economic Level as an Omitted Contextual Factor

5.5. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Typology | Description of Typology | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral - User Innovation | Outside existing institutions and market structures Individual- or community-level interventions Changing behavior, perception, and capabilities Operating at the periphery, disconnected from policies Positive but small-scale individual change Improved access to information and basic skills Short-term and temporary impact Foundation for higher-level innovation | Stage: Early Since the focus of change is on the individual and activities take place outside institutional efforts, this results in strengthening individual capability rather than changing the system eventually. This type represents the initial stage of social innovation and can advance to the mid-stage (integrated) or late stage (embedded) |

| Peripheral - Service Innovation | Developing new business models outside institutions Peripheral market operations Introducing new ways of solving social problems Addressing gaps in existing service or delivery mechanism Focusing on service delivery platform or business model level Improving access, efficiency, and social impact Remaining outside government policy or system Not being part of institutional frameworks Impact not at the level of the system or policy | Stage: Early & Middle This innovation can emerge at the early stage innovation phase. This is meant to test its marketability or propelled into a mid-stage phase through which gradual integration with institution is attained. It only affects local community levels or small markets but demonstrates a future possibility for ultimate integration with the institutional framework. |

| Peripheral - System Innovation | Initiating schemes like local currency or microfinance Lacking official recognition by institutions or policy Aiming for system change without altering core operations Duplicating some public institution functions Operating informally outside formal systems No impact on policy or institutional structures Operating in the informal realm Not influencing policy acceptance or institutional structures | Stage: Middle & Late At this stage, social businesses primarily emanate from early innovation and are linked to either institutions or markets. In some instances, the system becomes a necessary infrastructure at the local level, moving to the later stage of development. |

| Integrated - User Innovation | Changing user behavior and enhancing capabilities Becoming a part of existing programs or policies Extending beyond temporary campaigns Embedding in schools or public institutions for sustainability Operating within existing systems Promoting behavioral, cognitive, and capacity changes Emerging at the early or middle stages of social business | Stage: Early & Middle Initially, such initiatives operate in partnership-less within existing systems, focusing solely on individual change. In the mid-stage, impacts gradually integrate with existing systems, expanding their scope. |

| Integrated - Service Innovation | Collaborating with governments or public institutions Co-creation of new service models or operating systems Embedding services into public systems Redesigning existing service models without undergoing a complete structural overhaul Introducing changes at the service-delivery level Evolving from private-sector initiatives to public integration Incorporating through government policies or programs Enabling public–private collaboration for service delivery | Stage: Early, Middle, & Late This innovation can emerge at any stage of social business, most often beginning outside the system and then occurring in the middle stage. As its novelty begins to establish connections with systems, it can move on to the late stage in which novelty spreads its wings and scope. |

| Integrated - System Innovation | Connecting partially with public policy, law, or formal institutions Driving structural changes in operations or organizational structures Extending beyond a single region, organization, or individual Remaining limited in effect on the overall public system Creating and managing new systems with institutional cooperation Providing supplemental support to components of the formal system | Stage: Middle & Late This appears in the middle stage as partial linkages with policies or institutions take root, influencing the models or structures of operation. With demonstrated effectiveness, it receives institutional recognition evolving in the late stage into a supplemental but acknowledged part of a broader system increasing its structural impact and sustainability. |

| Embedded - User Innovation | Developing individual capacity within public institutions Ensuring continuity and periodicity inside formal systems Going beyond time-bound private projects Getting under public standards or policies Strengthening the rights, accessibility, and status of disadvantaged groups Creating new social norms Initiated as private programs then formalized through partnerships and policies Scaling programs to create permanent social impact | Stage: Middle & Late Such innovation emanates at the mid-stage when successful private initiatives start attracting public institutional support and later get formalized within the public systems as a guarantee of their future existence and ability to scale up. In the late stage, they become standard practice and wide-ranging social impact. |

| Embedded - Service Innovation | Institutionalizing social business service models within public systems Becoming a part of official public services Evolving from private-sector models to public service standards Incorporating into administrative manuals for sustained use Developing gradually, not instantaneously Accumulating results in markets and communities Obtaining public sector recognition for system integration | Stage: Middle & Late This innovation usually develops in the middle stage. Once their effectiveness is understood, they attract public sector attention which then gets formalized as official public service standards. In the later stages, these models become part of the stable and scalable components of public services. |

| Embedded - System Innovation | Embedding innovation within government policies, laws, or institutions Driving decisive changes in core structures or operating principles Creating new systems or orders beyond service or user levels Altering the structure and principles of the broader system Becoming part of national legislation or industry standards Restructuring value chains and market rules Achieving systemic change through official policies and laws | Stage: Late This innovation surfaces at the advanced stages of the social business resulting from considerable evidence of performance and validation of policy. Over a period, innovation upgrades from mere initial linkages to full institutional incorporation changing principles of operation, value chains, or even legislation. |

Appendix B

| Variable | Code & Definition | Application Criteria | Illustrative Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway of institutional change (initial/final) | Code 1 = Peripheral pathway Activities outside the institutional system operate autonomously without altering existing rules. | Initiatives not linked to public institutions, acting independently at margins. | “At the age of 20, José began volunteering to support vulnerable families in rural areas, creating grassroots solutions driven by community needs.” |

| Code 2 = Integrated pathway Partly connected with the institutional system, aligning with existing institutions without being fully embedded. | Programs are typically co-developed with government agencies or adapted from existing institutional structures. | “Over the past 20 years Marcelo has been evolving this platform, creating partnerships that link grassroots efforts to institutional frameworks for sustainable impact.” | |

| Code 3 = Embedded pathway Institutionalized within the system, structurally absorbed into public or regulatory frameworks. | The program becomes part of a formal system or is adopted as policy. | The organization continually works to promote specific legal regulation to change the status of sustainable development for rural areas to allow indigenous communities’ inclusion in disruptive and scalable industries, such as the energy and technology sectors, enabling them as business actors.” | |

| Innovation level (initial/final) | Code 1 = User level Focus on changing individual behavior, awareness, or capacity. | Training, education, or empowering individuals. | “Thismodel seeks to empower small coffee producers with knowledge and tools to improve their productivity and resilience.” |

| Code 2 = Service level Organizational or business model innovation delivering new services. | Introducing a platform, product, or new delivery mechanism. | “Theydeveloped structured programs and partnerships that provide scalable services to communities, from technical training to market access.” | |

| Code 3 = System level Innovation reshaping systems, markets, or institutional logics. | Establishing new value chains, financial systems, or ecosystem-wide models. | “Through its collaborative platform,itis shaping systemic solutions in the Amazon, integrating value chains and influencing markets and policies.” |

References

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; McGahan, A.M.; Prabhu, J. Innovation for Inclusive Growth: Towards a Theoretical Framework and a Research Agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. Risk Sharing and Transactions Costs: Evidence from Kenya’s Mobile Money Revolution. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 183–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregas, R.; Kremer, M.; Schilbach, F. Realizing the Potential of Digital Development: The Case of Agricultural Advice. Science 2019, 366, eaay3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J. Innovation and Scaling for Impact: How Effective Social Enterprises Do It; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5036-0099-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, N.; Schankerman, M.; Van Reenen, J. Identifying Technology Spillovers and Product Market Rivalry. Econometrica 2013, 81, 1347–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Wincent, J.; Chase, S.R. What If We Are the WEIRD Ones? A Call (and Roadmap) for More Non-WEIRD Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2025, 49, 1223–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, D.; Holt, D. Social Entrepreneurship in South Africa: Exploring the Influence of Environment. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 525–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Santos, M.; Holt, D.; Littlewood, D.; Kolk, A. Social Entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 29, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Leca, B.; Boxenbaum, E. 2 How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 65–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, G.; Basu, S. Optimization or Bricolage? Overcoming Resource Constraints in Global Social Entrepreneurship. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Acad. Manage. J. 2013, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F. The Evolution of Social Innovation: Building Resilience Through Transitions; McGowan, K., Tjörnbo, O., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-78643-114-1. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, R. Rural Social Enterprises as Embedded Intermediaries: The Innovative Power of Connecting Rural Communities with Supra-Regional Networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G. The Process of Social Innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phills, J.A.J.; Deiglmeier, K.; Miller, D.T. Rediscovering Social Innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2008, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S. Exploring Social Innovation through Hybridity: The Case of a Norwegian Social Enterprise. Soc. Enterp. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F.; Antadze, N. Making a Difference: Strategies for Scaling Social Innovation for Greater Impact. Innov. J. 2010, 15, 519532. [Google Scholar]

- Cajaiba-Santana, G. Social Innovation: Moving the Field Forward. A Conceptual Framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 82, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölsgens, R.; Lübke, S.; Hasselkuß, M. Social Innovations in the German Energy Transition: An Attempt to Use the Heuristics of the Multi-Level Perspective of Transitions to Analyze the Diffusion Process of Social Innovations. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2018, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavul, S.; Chavez, H.; Bruton, G.D. When Institutional Change Outruns the Change Agent: The Contested Terrain of Entrepreneurial Microfinance for Those in Poverty. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative Social Innovation and (Dis)Empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, N.; Lonie, S. M-PESA: Mobile Money for the “Unbanked” Turning Cellphones into 24-Hour Tellers in Kenya. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2007, 2, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. Mobile Money: The Economics of M-PESA. 2011. NBER Working Paper, No 16721. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w16721/w16721.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G. Models of Core/Periphery Structures. Soc. Netw. 2000, 21, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; The information age; Second edition with a new preface.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4443-1951-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzichristos, G.; Nagopoulos, N. Social Entrepreneurs as Institutional Entrepreneurs: Evidence from a Comparative Case Study. Soc. Enterp. J. 2021, 17, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Mair, J.; Beckman, C.M. Researching Social Innovation: How the Unit of Analysis Informs the Questions We Ask. Rutgers Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, 153–165. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4317265 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Comini, G.M.; Fischer, R.M.; D’Amario, E.Q. Social Business and Social Innovation: The Brazilian Experience. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2021, 19, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Conceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and Divergences. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M.T.; Dacin, P.A.; Tracey, P. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 12031213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Entrepreneurship in and around Institutional Voids: A Case Study from Bangladesh. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 419435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashitew, A.A.; van Tulder, R.; Muche, L. Social Value Creation in Institutional Voids: A Business Model Perspective. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 1992–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, R.; Silalahi, M.; Sambodo, M.T.; Juwono, V. Understanding Rural Context in the Social Innovation Knowledge Structure and Its Sector Implementations. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 73, 1873–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, Y.; Kerlin, J.A. Social Entrepreneurship in Context: Pathways for New Contributions in the Field. J. Asian Public Policy 2021, 14, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello, G.; Fu, X.; Mohnen, P.; Ventresca, M. The Creation and Diffusion of Innovation in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Econ. Surv. 2016, 30, 884–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation; National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84875-071-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley-Duff, R.; Bull, M. Understanding Social Enterprise: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, LA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4462-9552-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gallouj, F.; Weinstein, O. Innovation in Services. Res. Policy 1997, 26, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.; Panetta, D. Savings Groups: What Are They? The SEEP Network, Saings-Led Financial Services Working Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; p. 64. Available online: https://www.findevgateway.org/paper/2010/06/savings-groups-what-are-they (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Mahedi, M.; Saha, A.; Pervez, A.K.M.K.; Shaili, S.J. Micro-Credit in Bangladesh: A Comprehensive Review of Its Evolution, Impact, and Challenges Using Quantitative and Qualitative Evidences. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2025, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwell, K. Digital Solutions for Poor Indian Farmers. 2019. The Borgen Project. Available online: https://borgenproject.org/digital-solutions-for-poor-indian-farmers/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Fund, G.C. Farmerline: Empowering Smallholder Farmers and Governments to Create Climate-Resilient Agribusinesses. 2024. Green Climate Fund. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/story/farmerline-empowering-smallholder-farmers-and-governments-create-climate-resilient (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Ashoka. Ashoka Envisions a World in Which Everyone Is a Changemaker. Available online: https://www.ashoka.org/en-us/about-ashoka (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Kauffman, S.A. At Home in the Universe: The Search for Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-19-509599-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Gegenhuber, T.; Thäter, L.; Lührsen, R. Pathways and Mechanisms for Catalyzing Social Impact through Orchestration: Insights from an Open Social Innovation Project. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2023, 19, e00366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.M.; Murdock, A. Social Innovation. Blurring Boundaries to Reconfigure Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 13:9780230280175. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Jacobi, N.; Chiappero-Martinetti, E.; Maestripieri, L.; Giroletti, T. Creating Social Value by Empowering People: A Social Innovation Perspective. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2024, 95, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, J.; Schwarz, M. Social Innovation: Concepts, Research Fields and International Trends. In Studies for Innovation in a Modern Working Environment-International Monitoring; IMA/ZLW & IfU: Aachen, Germany, 2010; Volume 5, Available online: https://sfs.sowi.tu-dortmund.de/storages/sfs-sowi/r/Publikationen/Soziale_Innovation_Publikationen/Social_Innovation_Concepts__Research_Fields_and_Trends.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Kshetri, N. 1 Blockchain’s Roles in Meeting Key Supply Chain Management Objectives. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Clegg, S.; Pollack, J. The Effect of Public–Private Partnerships on Innovation in Infrastructure Delivery. Proj. Manag. J. 2024, 55, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X. Vining in the Blind: The Perils of Survivorship Bias. Adv. Econ. Manag. Polit. Sci. 2024, 72, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| User-Level | Service-Level | System-Level | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral pathway | Type 1. Peripheral–User Focus on individual change. Outside the institutional system Early | Type 2. Peripheral–Service Focus on service change. Outside the institutional system Early & Middle | Type 3. Peripheral–System Focus on system change. Outside the institutional system Middle & Late |

| Integrated pathway | Type 4. Integrated–User Focus on individual change. Partly connected to the institutional system Early & Middle | Type 5. Integrated–Service Focus on service change. Partly connected to the institutional system Early & Middle & Late | Type 6. Integrated–System Focus on system change. Partly connected to the institutional system Middle & Late |

| Embedded pathway | Type 7. Embedded–User Focus on individual change. Institutionalized within the system Middle & Late | Type 8. Embedded–Service Focus on service change. Institutionalized within the system Middle & Late | Type 9. Embedded-System Focus on system change. Institutionalized within the system Late |

| Variable Name | Definition | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Initial pathway of institutional change | Extent to which social business relates to or works beyond the institutional systems at its origin Whether the business starts functioning on the periphery, in partial integration, or in an embedded way with existing structure | Peripheral pathway = 1 Runs outside existing systems, no degree of functional integration Integrated pathway = 2 Connected to or working together with existing systems Embedded pathway = 3 Functionally integrated into, or taking the place of, existing systems |

| Final pathway of institutional change | Present degree of integration with institutional systems that the social business has attained by the year 2025. This illustrates whether, across time, the business has sustained a peripheral status, undergone integration, or been implanted into formal structures | Same coding criteria as initial pathway of institutional change |

| Initial innovation level | Extent of innovation characterizing business at commencement, differentiating whether innovation mainly addressed individual users, organizational services, or broader systemic arrangements | User-level innovation = 1 Focuses on changes in individual capabilities, behaviors, or awareness Service-level innovation = 2 Innovates the service itself, its delivery method, or business model at the level of a specific organization, community, or market segment System-level innovation = 3 Establishes or reshapes structural systems (e.g., value chains & distribution and standardization systems) to create sustainable ecosystems involving multiple stakeholders |

| Final innovation level | Present degree of innovation the business displays by 2025, reflecting whether its effect remains at the user level, has developed into new services and models, or has grown through systemic change | Same coding criteria as initial innovation level |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.H. A Dual-Axis Framework for Social Innovation: Mapping Dynamic Transitions Through 121 Social Businesses in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198964

Han JH. A Dual-Axis Framework for Social Innovation: Mapping Dynamic Transitions Through 121 Social Businesses in Developing Countries. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198964

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Joon Hye. 2025. "A Dual-Axis Framework for Social Innovation: Mapping Dynamic Transitions Through 121 Social Businesses in Developing Countries" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198964

APA StyleHan, J. H. (2025). A Dual-Axis Framework for Social Innovation: Mapping Dynamic Transitions Through 121 Social Businesses in Developing Countries. Sustainability, 17(19), 8964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198964