1. Introduction

Since the United Nations introduced the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) in 2006, emphasizing corporate social responsibility, ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) has emerged as a major topic in both academia and the business world. However, the global adoption of ESG practices remains highly uneven. While Europe and North America enforce strong ESG-related regulations, leading to active corporate participation, other regions show relatively lower adoption rates [

1]. For example, especially in emerging markets experiencing rapid economic growth, firms’ profitability tends to be prioritized over corporate social responsibility. South Korea, having only recently joined the ranks of developed nations, falls into this category.

This study empirically examines how ESG performance influences financial performance and firm value in Korean firms. Prior research suggests that Western investors pay close attention to the ESG performance of target companies, and firms with strong ESG performance tend to achieve superior financial outcomes compared to their peers [

2]. This raises the following question: Can publicly listed companies in South Korea enhance their financial performance and firm value through ESG initiatives to the same extent as Western companies? This study aims to provide a concrete answer to this question.

Recognizing that ESG investment and performance may be shaped by the institutional and cultural environment that firms face [

3], this research explores the moderating effects of three corporate governance factors deemed particularly relevant to the Korean context: (1) CEO tenure, (2) the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, and (3) foreign ownership ratio.

In Korea, the business landscape is heavily influenced by so-called chaebol, large, family-controlled business conglomerates [

4,

5]. Family businesses benefit from a stable governance structure that enables long-term and consistent policy implementation. Thus, this study investigates whether prolonged CEO tenure and the high shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder encourage proactive ESG investment in Korean firms. Additionally, Korean firms with high foreign ownership are generally expected to exhibit greater management transparency due to the demands of diverse stakeholders [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Given this, we explore how foreign ownership—measured as a proxy for management transparency—moderates the ESG performance–financial performance and ESG performance–firm value relationships.

Ultimately, this study evaluates whether the common assertion that ESG activities positively influence firm performance and shareholder value remains valid in the context of Korea’s unique corporate governance structure. While corporate governance in the United States and Europe underwent significant improvements following the Enron scandal [

10], such progress has been relatively slow in Korea. However, awareness of the need for governance reform to enhance global competitiveness has also been growing in Korea, prompting increased financial and non-financial disclosures by companies [

11]. Notably, the number of firms publishing sustainability reports, which are directly linked to ESG activities, rose from 38 in 2020 to 131 in 2022. With an expanding dataset, this study leverages these disclosures to conduct its analysis.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. ESG Management

ESG management refers to a corporate strategy that integrates non-financial values derived from environmental, social, and governance factors into business operations to achieve sustainable management, going beyond merely maximizing shareholder value [

12]. A related concept is Creating Shared Value (CSV), which emphasizes that businesses can simultaneously generate economic and social value [

13]. Unlike CSV, which focuses on practical methodologies for achieving this dual objective, ESG focuses instead on establishing formal guidelines and evaluation frameworks for corporate responsibility and sustainability.

In Korea, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy introduced the ‘K-ESG (Korean Environmental, Social, and Governance) Guidelines’ in 2021 to support corporate sustainability. This framework includes five ESG reporting indicators (e.g., formalities, content), 17 environmental indicators (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption), 22 social indicators (e.g., employee retention, industrial accident rates), and 17 governance indicators (e.g., board independence, audit committee effectiveness). As ESG gains traction beyond regulatory compliance, the concept has also begun to encompass what is known as ‘socially responsible investing’, along with related terms such as ‘ethical investing’ and ‘impact investing’.

ESG consists of the following three pillars. First, the “E”, which stands for “Environmental”, encompasses aspects such as carbon emissions, resource efficiency, and pollution control with the aim of achieving long-term environmental sustainability [

14]. Korea’s Green New Deal, introduced in 2020, aligns with these objectives. Today, many countries around the world are implementing a variety of environmental regulations based on international climate change agreements. As a result, corporate efforts to protect the environment have a significant impact on a company’s image and brand value, making the consideration of environmental factors in business operations no longer a choice, but a necessity.

Second, the “S”, which stands for “Social”, encompasses corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, including fair trade, transparency, community engagement, and labor rights [

15]. While CSR is generally perceived as beneficial, some Korean studies suggest that it may negatively impact financial performance by reducing net profits, particularly in the context of the Korean management environment [

16,

17]. However, since the 1990s, growing calls for companies to actively fulfill their responsibilities as members of society have led CSR activities—especially among large multinational corporations—to be recognized as a critical aspect of business management.

Lastly, the “G”, which stands for “Governance”, refers to a transparent and reliable decision-making and execution system that enables companies to create both environmental and social value by companies. This includes, for example, the proper composition of the board of directors, the establishment of audit committees, internal controls, and ethical management. In South Korea, governance issues have often been prominent due to the chaebol system, which is based on familial ownership and control. In fact, public perception of chaebols was largely negative, at least until the early 2000s, due to issues such as power struggles within families during management succession and closed decision-making processes [

18,

19]. The governance structure of chaebols has been heavily criticized for concentrating ownership within a specific family, thereby facilitating the hereditary succession of management rights and allowing those in control to easily evade responsibility even in cases of managerial failure. However, chaebol governance also has the advantage of enabling the active use of internal markets, thereby creating unique economic and synergistic effects. As a result, recent studies have begun to explore how chaebol governance influences ESG activities [

20].

2.2. Relationship Between ESG Performance and Firm Performance

This study considers firm performance in two dimensions: (1) financial performance (operating return on assets, OROA), and (2) firm value (Tobin’s q). Financial performance emphasizes past achievements and corporate stability, serving as a retrospective, results-oriented indicator primarily used for communication with internal stakeholders. In contrast, firm value highlights the potential for long-term value creation and functions as an investment-focused, forward-looking indicator mainly used in communication with external stakeholders. Therefore, analyzing these two complementary indicators together is expected to provide a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of how ESG performance impacts overall firm performance.

A series of previous studies examining the relationship between ESG performance and firm performance have yet to reach a definitive conclusion. Empirical research conducted on Korean firms has reported that ESG performance positively impacts profitability and cash-generating ability [

21], discretionary accruals [

22], firm value [

23,

24], free cash flow [

25], and corporate bond credit ratings [

26]. Similar findings are also evident in international research. For example, one of the meta-analyses reported that out of approximately 2000 studies analyzing the ESG–firm performance relationship, 62.6% confirmed a positive correlation between the two variables [

27]. Likewise, companies with above-average ESG ratings exhibited significantly higher financial performance and corporate value compared to those with lower ratings [

28].

However, not all studies report such positive outcomes. Empirical evidence indicates a negative relationship between K-ESG environmental indicators and cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) [

29]. A similar pattern is observed for ESG—particularly the environmental and social dimensions—in relation to firm value [

30]. In an international context, an analysis of 599 companies across 28 countries suggests that the link between corporate social responsibility and performance is not direct but is mediated by firms’ intangible resources [

31]. Furthermore, firms’ participation in voluntary environmental programs targeting greenhouse gas reduction has been associated with a decline in CAR [

32].

How, then, can these conflicting research findings be interpreted? The rationale—or, more precisely, the normative justification—of ESG activities can largely be explained through the following three theoretical perspectives: (1) stakeholder theory, (2) institutional theory, and (3) legitimacy theory.

Stakeholder theory emphasizes the importance of balancing the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders, while institutional theory adds that organizations adapt to societal norms and industry practices to secure legitimacy [

33], and legitimacy theory further explains that such alignment with social values is essential for maintaining societal approval [

34]. All these three theoretical perspectives certainly provide a normative rationale for why companies should engage in ESG activities. However, strictly speaking, they do not address whether ESG activities yield positive returns. Certainly, various inferences can be drawn in this regard. Yet, one crucial point must be emphasized: all of the aforementioned theories fundamentally underscore the importance of the social environment surrounding firms’ business. Therefore, the outcomes of ESG activities are likely to vary greatly depending on the specific societal context and the perceptions of individuals within that society.

This implies that studies examining the impact of ESG on firm performance must adequately account for the unique social factors of the society in which the firm operates. Certainly, there is a clear need for future studies to approach this issue from a comparative perspective. Against this backdrop, the present study aims to empirically investigate the relationship between ESG performance and firm performance, specifically focusing on Korean firms. Based on discussion thus far, the study proposes the following working hypotheses:

H1a. ESG performance positively influences financial performance.

H1b. ESG performance positively influences firm value.

2.3. Moderating Effect of CEO Tenure

As ultimate decision-makers, CEOs play a critical role in determining corporate strategy and resource allocation, and their decisions directly impact the implementation of ESG management. According to upper echelons theory, a company’s ESG activities can be largely influenced by the CEO’s cognitive paradigm (e.g., their attitude toward ESG) and the degree of alignment between this cognitive paradigm and the external environment in which the firm operates (e.g., the presence of a board of directors capable of overseeing the CEO’s decisions) [

35]. In this context, CEO tenure serves as a meaningful moderating variable [

36].

CEOs with shorter tenures, acting as agents of shareholders, tend to focus on gaining the trust of the board of directors. As a result, they are more likely to prioritize short-term financial performance, which may limit their ability or willingness to develop and implement long-term, non-financial strategies such as ESG initiatives [

37,

38]. In contrast, long-tenured CEOs acquire greater firm-specific knowledge and have more opportunities to build strong relationships with stakeholders. This enables them to pursue higher-risk, long-term strategies including those related to ESG.

In other words, CEOs in the early stages of their tenure are more likely to focus on achieving short-term results by leveraging existing resources and capabilities, whereas CEOs with longer tenure are more inclined to focus on the creation of new value—such as ESG activities—that contributes to long-term performance. As CEO tenure increases, opportunities to consolidate power within the firm also grow. This not only reduces the pressure they face from the board regarding performance but also increases their influence over corporate decision-making [

39].

Of course, an opposing line of reasoning can also be considered. In general, newly appointed CEOs tend to prefer aggressive decision-making to demonstrate their capabilities, whereas long-tenured CEOs often favor safer decisions as part of a risk management approach [

40]. In this regard, compared to their long-tenured counterparts, short-tenured CEOs are more likely to engage in greater levels of strategic investment [

41]. This suggests that investment decisions made early in a CEO’s tenure may have a greater impact on the firm’s long-term performance. Within this context, CEOs may in fact be more active in pursuing ESG activities during the early stages of their tenure, potentially leading to higher ESG performance. Conversely, as CEO tenure increases, reduced pressure from the board and other stakeholders may lead to a decline in ESG engagement.

The coexistence of these opposing arguments ultimately suggests that the effect of CEO tenure on ESG management is largely contingent upon the prevailing cultural or institutional context within a given society. In this context, the present study expects that the former logic is more applicable in the Korean context—namely, that longer CEO tenure strengthens the positive relationship between ESG performance and both financial performance and firm value. In many Korean conglomerates (chaebols), key strategic decisions are often made by family members who are also among the firm’s largest shareholders, many of them concurrently serve as both CEO and chair of the board. This implies that, in many large Korean firms, CEOs often hold substantial control over corporate operations through extended tenures, enabling them to exert considerable influence on overall management.

Within this context—and particularly in light of the structural characteristics of Korean firms—longer CEO tenure is expected to be associated with more sophisticated and strategically oriented long-term investments, including those related to ESG management. Based on the above discussion, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2a. The longer CEOs’ tenure, the greater the positive impact ESG performance will have on financial performance.

H2b. The longer CEOs’ tenure, the greater the positive impact ESG performance will have on firm value.

2.4. Moderating Effect of the Shareholding Ratio of the Largest Shareholder

When a CEO holds a significant equity stake, they acquire substantial decision-making authority and control over the company. According to agency theory, unlike dispersed shareholders, majority shareholders tend to prioritize long-term value creation over short-term financial performance [

42]. In this context, CEOs with high ownership stakes are expected to engage more actively in ESG management, leveraging a stable management environment to enhance shareholder value over the long term.

However, an opposing perspective suggests that when a CEO has high stake of ownership, the firm may be less vulnerable to hostile takeovers or external governance pressures. This reduced external discipline can lead to managerial complacency, which may ultimately result in a decline in firm performance and a diminished emphasis on ESG management. Supporting this view, firms with high ownership concentration among controlling shareholders tend to exhibit lower corporate value compared to those with more dispersed ownership structures [

24].

In the same vein as CEO tenure, this study argues that the effect of the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder on ESG management is also contingent upon the cultural or institutional context of a society. More specifically, the former reasoning based on agency theory is expected to offer a more accurate explanation of corporate behavior in the Korean context where owner-CEO duality persists. Thus, it is assumed that majority shareholders not only pursue private benefits but also invest in ESG initiatives to cultivate positive stakeholder relationships, thereby enhancing the firm’s long-term firm performance. Based on this assumption, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a. The higher the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, the stronger the positive effect of ESG performance on financial performance.

H3b. The higher the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, the stronger the positive effect of ESG performance on firm value.

2.5. Moderting Effect of Foreign Ownership

In Korea, investors in the stock market are typically categorized into three groups: foreign investors, institutional investors, and retail investors. Among these, foreign investors—such as global investment banks, insurance firms, pension funds, and sovereign investment funds—hold substantial capital (accounting for over 30% of total market value) and, unlike domestic institutional investors, generally maintain more independent relationships with the firms in which they invest. As a result, they have strong incentives to actively monitor corporate management.

Given this context, foreign institutional investors are likely to be particularly responsive to long-term performance drivers, such as ESG management. Prominent global financial institutions, such as BlackRock, Inc., have played a pivotal role in elevating ESG management to a mainstream investment consideration. The number of institutional investors incorporating ESG factors into their investment decisions-making has also grown steadily [

43]. Therefore, firms with higher levels of foreign ownership are expected to place greater emphasis on ESG management.

Several studies have confirmed that Korean firms with high foreign ownership tend to be more responsive to shareholder demands and adopt more transparent management practices, ultimately achieving higher firm value. For instance, firms with higher foreign ownership incur lower entertainment expenses—an indicator of more transparent management—and, as a result, exhibit higher firm value [

6]. Similarly, firms with greater foreign ownership receive higher credit ratings and exhibit lower earnings forecast errors, suggesting more transparent financial management [

7]. More recent evidence indicates that foreign equity participation enhances firms’ accounting transparency in Korea, thereby contributing to improved stock market performance [

9].

In addition, higher foreign ownership has been associated with increased dividend payouts, which serve as an important criterion in evaluating corporate social responsibility (CSR) [

44]. A positive relationship between foreign ownership and firm value has also been empirically confirmed [

45]. Furthermore, firms with higher foreign ownership tend to be more actively engaged in CSR activities [

46].

Clearly, the positive effects of foreign ownership—or more precisely, the inflow of external capital—are not unique to Korea. Nevertheless, such effects are likely to be particularly salient in the Korean context, where corporate governance is predominantly owner-centered and closed in nature, while the economy simultaneously maintains a small, open-market orientation that renders firms highly sensitive to external pressures. Based on the argument, this study hypothesizes that firms with higher levels of foreign ownership are more likely to adopt ESG management practices due to the stringent monitoring exercised by foreign investors. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4a. The higher the foreign ownership ratio, the stronger the positive effect of ESG performance on financial performance.

H4b. The higher the foreign ownership ratio, the stronger the positive effect of ESG performance on firm value.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The sample used in this study consists of balanced panel data from 1860 publicly listed firms in Korea over the 2020–2022 period (620 firms per year). The data were sourced from DART (Data Analysis, Retrieval and Transfer System), an electronic disclosure platform operated by the Financial Supervisory Service of South Korea. Given that ESG disclosures remain voluntary in Korea, previous studies have often relied on various types of sustainability reports with differing assessment criteria to increase sample size. However, this study exclusively utilizes ESG ratings provided by Korea ESG Standards Institute (K-ESG), which comply with Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) 4.0 and K-ESG Guidelines. Firms with missing financial data or ESG ratings were excluded from the sample.

The variables are measured as follows. The independent variable, ESG performance, is assessed using K-ESG’s ESG ratings. Since its establishment in 2002, K-ESG has played a pivotal role in promoting corporate governance reform in Korea. In 2011, it expanded its assessment framework to include the environmental (“E”) and social (“S”) dimensions, resulting in a comprehensive ESG rating system with seven levels: S, A+, A, B+, B, C, and D. K-ESG rating methodology is well aligned with international standards such as OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) Principles of Corporate Governance and ISO (International Organization for Standardization) 26000 [

47], while also reflecting Korea’s unique legal and business environment. This study incorporates both the composite ESG ratings and the individual scores for each of the three subcomponents—environmental, social, and governance performance.

The dependent variables—financial performance and firm value—are measured using Operating Return on Assets (OROA) and Tobin’s q, respectively. OROA is calculated by dividing firms’ operating income by their total assets and is considered more appropriate than traditional ROA for evaluating the efficiency of a firm’s core business operations. Tobin’s q is calculated by dividing firms’ total market value by its total asset value; a ratio greater than 1 suggests overvaluation, while a ratio below 1 indicates undervaluation. One potential concern is that firm performance during the 2020–2022 period may have been unevenly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. To address this, the study uses the average values over the three-year period (2020–2022) to mitigate potential distortions.

The moderating variables—CEO tenure, the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, and foreign ownership ratio—are obtained from KIS-Value, a financial data platform operated by NICE information service Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea. The control variables include sustainability report disclosure status, firm size, CEO age, CEO duality (i.e., whether the CEO also serves as board chair), industry classification, firm age, and debt ratio.

Sustainability report disclosure status is a binary variable coded as 1 if a firm regularly publishes sustainability reports and 0 otherwise. Firm size is measured by market capitalization. CEO age is obtained from publicly disclosed records available through DART. CEO duality is coded as 1 if the CEO serves as board chair and 0 otherwise. Industry classification is based on the KIS-IC (Korea Information System Industrial Classification) code. Data on firm age and debt ratio are sourced from KIS-Value.

3.2. Research Model

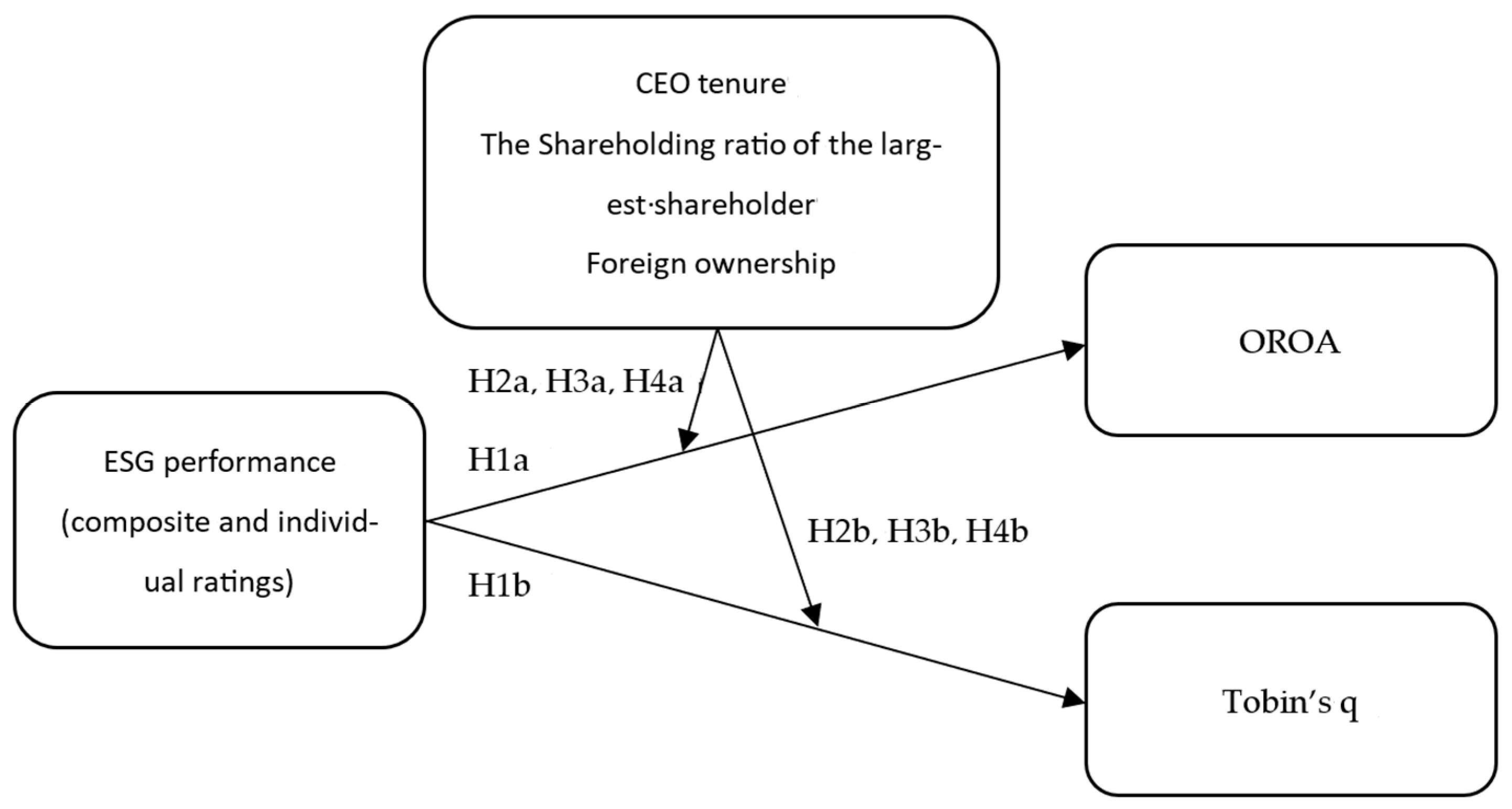

Based on the hypotheses developed in the preceding sections, the research model is illustrated in

Figure 1. The model is also represented in Equations (1) and (2), which incorporate all control variables. A brief description of each variable is attached in

Table 1.

4. Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

This study collected ESG composite scores, along with individual scores for the environmental, social, and governance dimensions, as disclosed by K-ESG from 2020 to 2022. A total of 7440 ratings were obtained, and their distribution of scores across rating categories is presented in

Table 2 below. Notably, while an “S” rating category exists, the number of firms that received this rating was extremely small. Therefore, it was combined with the A+ category. With the exception of the social performance dimension, the proportion of firms receiving an A+ rating was approximately 1%.

Next,

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study.

Table 4 presents sample distribution by industry. The mean value of OROA, the dependent variable, is 0.028, with a minimum of −0.682 and a maximum of 0.274. The mean value of Tobin’s q, another dependent variable representing firm value, is 0.080, with a minimum of 0.011 and a maximum of 0.400.

With regard to ESG performance, the mean values are as follows: 2.980 for composite ESG performance, 2.564 for environmental performance, 3.344 for social performance, and 3.204 for governance performance. Among these, environmental performance score is the lowest, likely due to the presence of stricter evaluation criteria defined by international standards such as ISO 14001 [

48] and ISO 26000.

The average CEO tenure is 12.884 years, and this variable was rescaled to a standardized range between 0 and 1 for analysis. Among the control variables (CAGE, CEOD, DETR, FAGE, INDS, SIZE, SUST), firm size (SIZE) was measured as the natural logarithm of total assets in the corresponding year and was likewise scaled between 0 and 1. CEO age (CAGE) and firm age (FAGE) was also rescaled for consistency. CEO duality and sustainability report disclosure (SUST) are measured as dummy variables.

For industry classification, this study employed the KIS-IC system, which is modeled after the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS), originally developed jointly by Standard &Poor’s Global, New York, USA and MSCI, New York, USA for application in securities markets. The sample was classified according to the first two digits of the KIS-IC code, corresponding to the sector level.

Table 4 presents the correlation coefficient among the variables used in this study. ESG composite performance shows a positive correlation with both financial performance (r = 0.221,

p < 0.01) and corporate value (r = 0.190,

p < 0.01). Environmental performance is positively correlated with financial performance (r = 0.240,

p < 0.01) and corporate value (r = 0.163,

p < 0.01). Social performance is positively correlated with financial performance (r = 0.220,

p < 0.01) and corporate value (r = 0.189,

p < 0.01). Finally, governance performance also shows a positive correlation with financial performance (r = 0.172,

p < 0.01) and corporate value (r = 0.149,

p < 0.01). To check for multicollinearity, a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis was conducted. All VIF values were found to be below 5, indicating that multicollinearity is not a significant concern in the model.

Table 5 presents the correlation coefficient among the variables used in this study. ESG composite performance shows a positive correlation with both financial performance (r = 0.221,

p < 0.01) and firm value (r = 0.190,

p < 0.01). Environmental performance is positively correlated with financial performance (r = 0.240,

p <

0.01) and firm value (r = 0.163,

p < 0.01). Social performance is positively correlated with financial performance (r = 0.220,

p < 0.01) and firm value (r = 0.189,

p < 0.01). Finally, governance performance also shows a positive correlation with financial performance (r = 0.172,

p < 0.01) and firm value (r = 0.149,

p < 0.01). To check for multicollinearity, a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis was conducted. All VIF values were found to be below 5, indicating that multicollinearity is not a significant concern in the model.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

Table 6 presents the multiple regression analysis results for H1a and H1b. The findings indicate that ESG composite performance, as well as its individual components are all positively and statistically significantly associated with both financial performance and firm value.

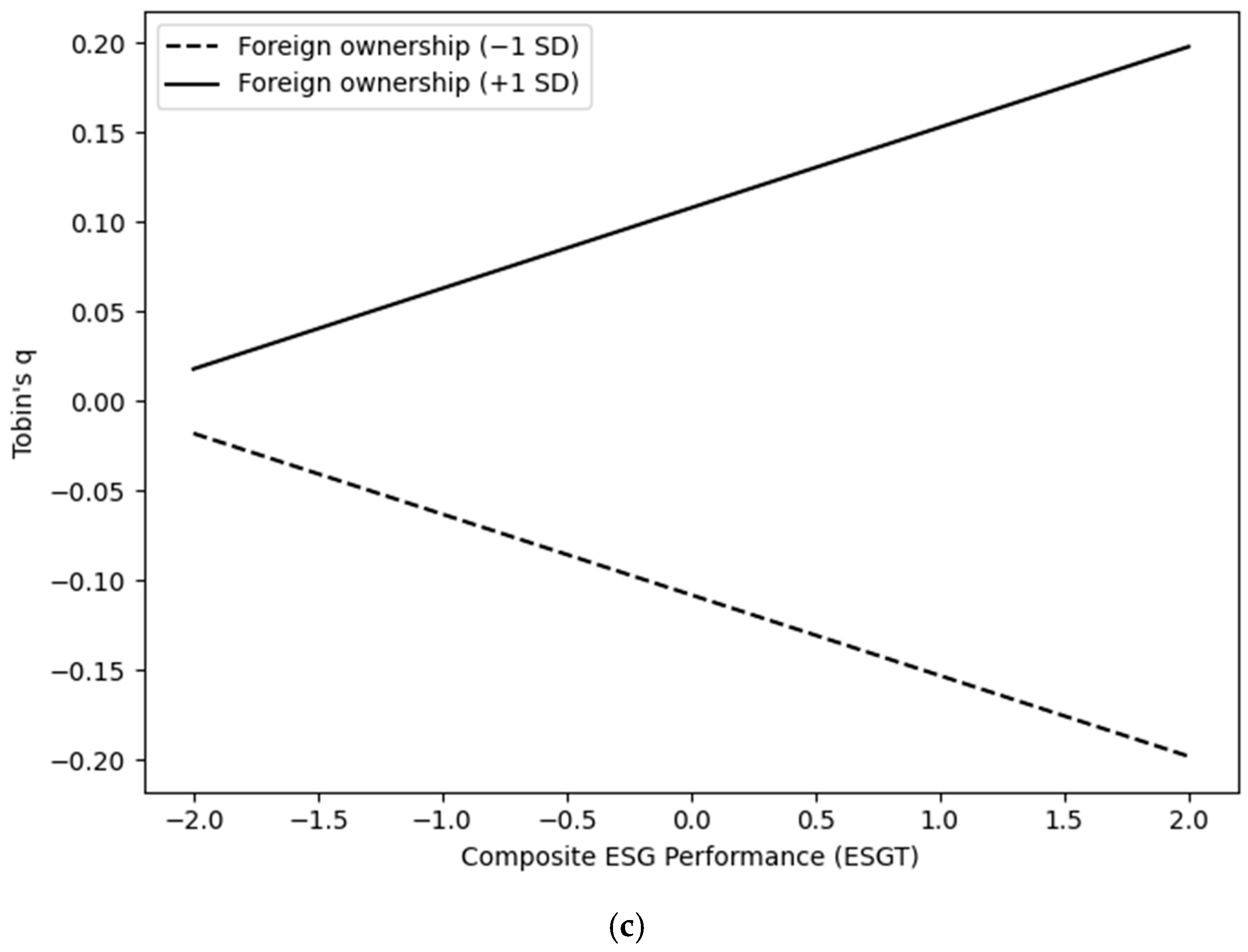

Table 7 presents the results of the moderation analysis, testing the effects of CEO tenure, the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, and foreign ownership ratio on the relationship between ESG composite performance and firm performance. When firm performance is measured using OROA (financial performance), only the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder demonstrates a statistically significant moderating effect. In contrast, when firm performance is measured using Tobin’s q (firm value), both CEO tenure and the foreign ownership ratio show statistically significant moderating effects.

Figure 2 provides interaction plots that visually illustrate each of these moderating effects.

Table 8 summarizes the results of the hypothesis testing.

To further rigorously test the moderating effects of these three variables, a multiple regression analysis was conducted using the individual ESG performance components—environmental, social, and governance performance—as independent variable. The results were consistent with those obtained when ESG composite performance was used as the independent variable.

First, when financial performance was used as the dependent variable, only the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder showed a statistically significant moderating effect across all three dimensions. Specifically, when environmental performance was used as the independent variable, the interaction term coefficient (ESCR × OWNR) was 0.022 (p = 0.036). When social performance was used instead, the interaction term coefficient (SSCR × OWNR) was 0.034 (p = 0.001). Lastly, when governance performance was used, the interaction term coefficient (GSCR × OWNR) was 0.029 (p = 0.026).

Next, when firm value was used as the dependent variable, only CEO tenure and foreign ownership showed statistically significant moderating effects across all three ESG components. Specifically, when environmental performance was used as the independent variable, the interaction terms coefficients (ESCR × CEOY and ESCR × FRGN) were 0.016 (p = 0.039) and 0.020 (p = 0.012), respectively. When social performance was used, the interaction terms coefficients (SSCR × CEOY and SSCR × FRGN) were 0.013 (p = 0.056) and 0.044 (p = 0.000), respectively. Lastly, for governance performance, the interaction terms coefficients (GSCR × CEOY and GSCR × FRGN) were 0.024 (p = 0.018) and 0.052 (p = 0.000), respectively.

In addition, the same regression analysis was conducted on the extended sample collected at the early stage of the study to test the robustness of the model. This sample consists of a total of 2279 observations and includes firms with only one or two years of ESG ratings as well. (The original sample included 620 firms with 1860 observations for which ESG ratings were available spanning three years). The analysis showed that the direction of the coefficients was consistent across both analyses; however, some differences in statistical significance were observed, particularly regarding the moderating effects. Specifically, the interaction term between ESG Composite Performance and CEO tenure was statistically significant in the regression model using OROA as the dependent variable, but not in the model with Tobin’s q.

Subsequently, the study also conducted the same regression analysis separately for subsamples of firms classified as manufacturing and service sectors. The analysis revealed differences between the two sectors with respect to the moderating effects. Specifically, the moderating effect of CEO tenure was significant only in the service sector, whereas that of the foreign ownership ratio was significant only in the manufacturing sector. These findings indicate the importance of considering industry-specific characteristics in future ESG research.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to examine the impact of ESG performance on firm performance using Korean firms as the sample. It also sought to empirically verify whether the unique characteristics of Korea’s corporate governance structure have a moderating effect on the relationship between these two variables. The findings of the study can be summarized as follows. First, ESG performance was found to have a statistically significant positive effect on both financial performance and firm value. These results are largely consistent with those reported in prior international research.

However, as shown in

Table 3, it is worth noting that the average environmental score (M = 2.564) was significantly lower than that of social (M = 3.344) and governance dimensions (M = 3.204). As mentioned earlier, while clear standards for environmental performance have been established by various international certification bodies, it is likely that the social and governance dimensions are more strongly influenced by the unique institutional and cultural contexts of individual countries. Given the growing importance of supply chain collaboration in achieving superior ESG performance, this suggests that K-ESG should consider further aligning its social and governance assessment criteria with global standards.

Several factors may explain why Korean firms exhibit relatively lower environmental performance. One likely explanation is that many Korean companies have yet to establish fully integrated, company-wide environmental management systems, resulting in lower ratings. In addition, unexpected incidents such as explosions, fires, or hazardous material leaks may have negatively impacted environmental ratings for some firms. For instance, S-Oil’s environmental rating dropped significantly in 2022 following an explosion at its Onsan plant. Carbon neutrality also presents a distinct challenge, as compliance with carbon regulations requires sustained, long-term efforts. Furthermore, since environmental standards differ significantly across industries, environmental performance varies according to sector-specific characteristics. Given Korea’s relatively high concentration of manufacturing industries compared to other countries of similar economic scale, Korean firms may face greater structural challenges in meeting environmental criteria.

With respect to moderating effects, CEO tenure and foreign ownership significantly strengthened the link between ESG performance and firm value but showed no such effect on financial performance. In contrast, the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder enhanced the ESG-financial performance relationship but did not influence the ESG-firm value relationship. These findings suggest that the impact of ESG management may differ depending on whether performance is measured in financial or market-based terms.

Although financial performance and firm value are closely linked, the former focuses on short-term profitability, while the latter reflects long-term value based on stock price expectations. The findings suggest that majority shareholders tend to focus on the immediate impact of ESG investments on financial performance (e.g., profit maximization and dividends), whereas CEOs and foreign investors are more concerned with the long-term effects of ESG investments on firm value (e.g., stakeholder relationships and share price growth). One possible explanation for this difference is that, within the Korean context, majority shareholders may be particularly sensitive to the short-term financial implications of ESG investments.

The finding that the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder does not positively moderate the ESG–firm value relationship contradicts prior research. When the ownership stake of the largest shareholder is relatively low, internal and external monitoring mechanisms may function effectively, promoting stable and accountable governance that enhances firm value. However, when ownership concentration becomes too high, these monitoring mechanisms may weaken, potentially amplifying the adverse effects of concentrated control. This implies that the relationship between majority shareholder ownership and firm value may follow a U-shaped pattern rather than a simple positive or negative linear form. Supporting this notion, prior evidence shows that firm value tends to increase as ownership by the largest shareholder rises to 7%, decreases as it approaches 38%, and then increases again once it exceeds 38% [

49]. Future studies should consider examining this non-linear relationship between ownership concentration and firm value.

Despite the differential impacts of ESG management on financial performance and firm value, the interaction term coefficients for all moderating variables were positive, in line with the study’s hypotheses. This suggests that firms with longer CEO tenure, a higher shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, and greater foreign ownership are more likely to engage actively in ESG initiatives and implement them successfully. ESG should be viewed as a long-term strategic commitment rather than a short-term project. Effective ESG management requires a stable corporate governance structure—characterized by sustained CEO leadership, balanced shareholder control, and active monitoring by foreign investors and other external stakeholders.

From a policy perspective, the findings of this study highlight the critical role of stable governance structures in facilitating the adoption and success of ESG management. At the same time, they also suggest that excessive stability in governance may risk fostering short-termism, such as greenwashing, and thus requires careful monitoring. While the present study is limited to Korean firms and cannot confirm whether this relationship is stronger in Korea than in other countries, the prevalence of owner-CEO duality in Korea suggests that governance stability may play a particularly important role in driving successful ESG outcomes. This implies that in the Korean context, effective ESG implementation is likely to depend less on external push factors, such as regulatory pressure or stakeholder demands, and more on internal pull factors, notably the will and commitment of top executives. These insights point to the need for policies that not only strengthen institutional frameworks but also incentivize and cultivate leadership commitment to ESG values within firms.

From the perspective of institutional investors, the implications of this study are as follows. First, the findings suggest that ESG ratings can serve as a meaningful indicator for identifying potential investment targets among Korean firms. Second, while the corporate governance of Korean firms has long been considered relatively opaque by international standards, its impact on ESG management appears to be highly nuanced, likely due to Korea’s unique cultural and institutional characteristics. Institutional investors should therefore take these factors carefully into account when making investment decisions. Finally, the results indicate that foreign institutional investors have significant potential to exert a positive influence on the ESG management practices of Korean firms.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, as the disclosure of sustainability reports in Korea is still voluntary, there were limitations in obtaining a fully representative sample. Once sustainability reporting becomes mandatory in 2025 and ESG disclosure standards are further institutionalized, more comprehensive and accurate research will become feasible. In this study, all company-produced sustainability reports not disclosed via DART were excluded to ensure consistency and transparency in data collection.

Second, although industry classification was controlled using dummy variables, ESG standards and expectations vary widely across industries. For example, chemical companies are required to make substantial investments in carbon neutrality and resource recycling, whereas service-sector companies are subject to fewer environmental regulations and may achieve high ESG ratings with minimal investment. Future studies should examine the ESG–performance relationship at the industry level using sector-specific samples for more nuanced insights.

Third, due to the limited availability of ESG data for Korean firms, this study was unable to conduct full-scale panel analyses. Expanding the dataset to cover a longer period would improve the robustness of future research. While this study utilized three years of data (2020–2022), ESG evaluations were not widely available prior to 2020, limiting the feasibility of longitudinal analysis. However, beginning in 2025, with mandatory ESG reporting in place, a larger pool of firms with ESG ratings will emerge, enabling more advanced methodologies such as longitudinal and panel data regression.

ESG management has become one of the most important components of modern corporate strategy, with many firms actively planning and implementing ESG initiatives. As ESG compliance becomes a global norm, Korean companies must adapt swiftly to remain competitive. Future research will play a critical role in guiding the evolution of ESG management in Korea and enhancing the global competitiveness of Korean firms.