From Denial to Acceptance—Leveraging the Five Stages of Grief to Unlock Climate Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

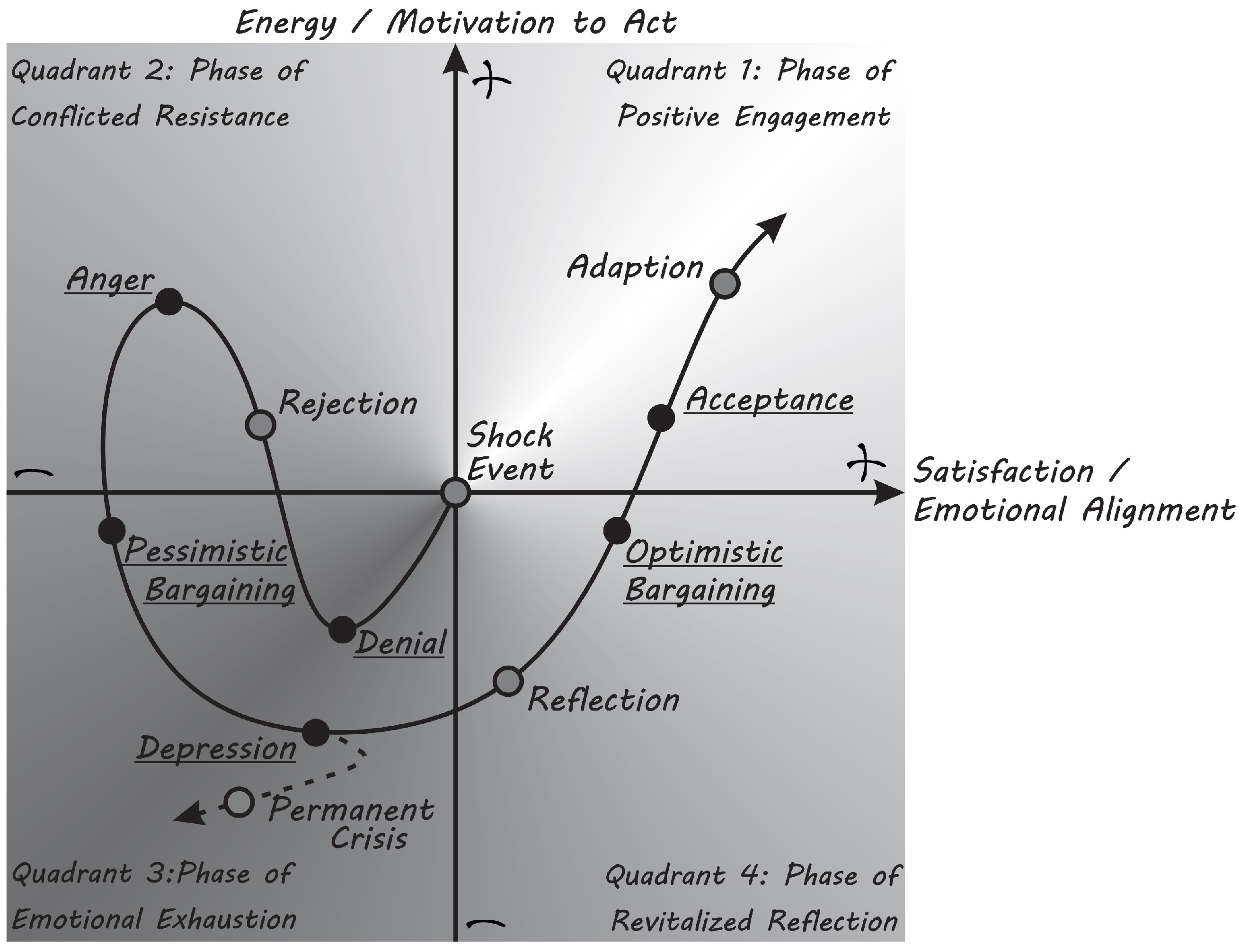

2. Materials and Methods: Comparative Analysis of the Five Stages of Grief in Response to Climate Change

- the Phase of Conflicted Resistance (high energy, low satisfaction);

- the Phase of Emotional Exhaustion (low energy, low satisfaction);

- the Phase of Revitalised Reflection (low energy, increasing satisfaction);

- the Phase of Positive Engagement (high energy, high satisfaction).

3. Results—Strategies for Overcoming the Stages of Grief in the Context of Climate Change

3.1. Denial

3.1.1. Psychological Foundations

3.1.2. Climate-Related Expressions and Societal Manifestations

- Scientific denial is the refusal to accept scientific evidence and proven data of climate change. Individuals may dispute the validity of climate change research or believe that natural climate cycles, not human activities, are responsible for the observed rapid changes in the climate. For example, in the 1960s and 1970s, scientists like Charles David Keeling systematically measured rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations, providing early empirical support for the greenhouse effect [43]. However, these findings received limited political and public attention at the time, partly because short-term cooling trends and scientific uncertainties led to widespread hesitation and undermined early recognition of the data’s significance [44]. As shown in Lewandowsky et al. (2015) [45], such denial can even influence the scientific community itself, leading to an overemphasis on uncertainty and a shift in language that aligns with contrarian narratives.

- Personal denial is the belief that climate change will not affect oneself or one’s community. Individuals may believe that they are immune to the effects of climate change, such as extreme weather events, rising sea levels, or food and water scarcity.

- Cultural denial is the belief that climate change is not a significant issue or that it is not a priority compared to other societal concerns. Individuals may believe that economic growth, national security, or other issues are more important than addressing climate change.

- Temporal denial is the belief that climate change is a problem for the future and not the present. Individuals may believe that the impacts of climate change will not affect them in their lifetime or that future technologies will solve the problem.

- Political denial is the failure of governments to acknowledge or act on climate change. Governments may be influenced by powerful lobbyists, short-term political goals, or public opinion that denies the existence or severity of climate change. For example, after the discovery of the ozone hole by British Antarctic Survey researchers in 1985 [46], the scientific link between chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and stratospheric ozone depletion gained new urgency. Nevertheless, leading chemical manufacturers such as DuPont initially questioned the strength of the evidence, referring to it as speculative and based on uncertain models [47]. Company representatives warned that a premature ban on CFCs could impose substantial economic risks without conclusive proof of environmental harm. Political actors and industry lobby groups echoed this scepticism, often downplaying the issue and calling for further study before regulatory measures were adopted [44,48]. Ultimately, these objections were overcome, and the 1987 Montreal Protocol phased out several industrial chemicals, including CFCs. Several fossil fuel companies, most notably ExxonMobil and the American Petroleum Institute, actively funded campaigns from the 1980s onwards that cast doubt on climate science. These campaigns sought to undermine public trust in climate models and emphasised economic harms of regulatory measures, despite internal knowledge of the risks associated with greenhouse gas emissions [49,50,51]. Furthermore, when the Kyoto Protocol was introduced in 1997 to limit greenhouse gas emissions, several governments and industry representatives opposed binding commitments, arguing that such measures would harm economic competitiveness and disproportionately affect developed nations. In the United States, the Senate pre-emptively rejected any treaty excluding developing countries, and the administration later withdrew from the protocol entirely [44,48]. In the early 2000s, certain political leaders and media figures continued to challenge the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change, framing it instead as a natural or cyclical phenomenon and downplaying the urgency of action [44,51].

- Redirecting responsibility shifts accountability away from systemic change by emphasising individual responsibility (e.g., carbon footprints) or by using “whataboutism” to argue that someone else, other countries or sectors should take action first.

- "Promoting non-transformative solutions" refers to arguments suggesting that disruptive change is unnecessary. Instead, they favour minimal or incremental approaches, such as technological optimism, which assumes that future innovations will resolve climate issues without significant policy shifts, or “fossil fuel solutionism,” where fossil fuel companies portray themselves as part of the solution to climate change.

- Emphasising the downsides focuses on the social and economic costs of climate policies, suggesting they may be more harmful than climate impacts themselves. Examples include arguments that climate policies threaten jobs or well-being, which may appeal to marginalised communities. This category also includes “policy perfectionism,” which argues for limited actions out of fear that ambitious policies could harm public support.

- Surrendering to climate change conveys doubt about the feasibility of climate mitigation. It includes “doomism”, the belief that catastrophic climate change is inevitable, mitigation efforts are pointless, and change is impossible, which portrays socio-economic reorientation as unrealistic. These views can foster resignation and hinder collective action.

3.1.3. Strategy: Education Drowns Denial

3.2. Anger

3.2.1. Psychological Foundations

3.2.2. Climate-Related Expressions and Societal Manifestations

3.2.3. Strategy: Dialogue Alleviates Anger

3.3. Bargaining

3.3.1. Psychological Foundations

3.3.2. Climate-Related Expressions and Societal Manifestations

3.3.3. Strategy: Empathy Guides Bargaining

3.4. Depression

3.4.1. Psychological Foundations

3.4.2. Climate-Related Expressions and Societal Manifestations

3.4.3. Strategy: Community Heals Depression

3.5. Acceptance

3.5.1. Psychological Foundations

3.5.2. Climate-Related Expressions and Societal Manifestations

3.5.3. Strategy: Acceptance Drives Adaptation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The temporal progression of emotional stages needs empirical validation: It is unclear whether and how individuals or communities move linearly through the five stages, revisit certain phases, or experience hybrid emotional states. Longitudinal and comparative studies could provide deeper insights into emotional trajectories in different social and cultural contexts. In addition, future research should examine whether and how targeted interventions, such as message framing or participatory formats, can support transitions between emotional stages and foster greater engagement.

- Emotions beyond the original Kübler-Ross model, such as hope, guilt, shame, or apathy, warrant closer examination. These affective states may play a crucial role in transitions between stages or in sustaining action, yet remain under-represented in grief-based models of engagement.

- Future research should explore emotional transitions in collective settings: How do emotional stages manifest in groups, institutions, or movements? Do communities share emotional trajectories, or are emotional responses fragmented across sectors and generations?

- There is a need for intervention studies that assess how psychologically informed communication, climate education, and therapeutic approaches can facilitate emotional readiness and support movement toward constructive engagement and acceptance.

- A promising avenue lies in educational and professional training. As highlighted by recent findings [123], the integration of climate-related emotional competence into psychology and education curricula remains limited. Research into pedagogical models and learning outcomes is essential to prepare future practitioners for the emotional complexities of climate change.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAPTNOW | ADAPTation Capacity Strengthening for Highly Affected and Exposed Territories |

| in the Alps NOW | |

| CFC | chlorofluorocarbon |

| ACT | acceptance and commitment therapy |

References

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; et al. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report: Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Koder, J.; Dunk, J.; Rhodes, P. Climate Distress: A Review of Current Psychological Research and Practice. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Zhao, K.; Ma, D.; Liu, H.; Amin, S.; Yasin, I. Global Climate Change, Mental Health, and Socio-Economic Stressors: Toward Sustainable Interventions across Regions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués-Bravo, D.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, F.; Orsini, L.; de Boer, E.; Jansson, R.; Morlon, H.; Fordham, D.A.; Jackson, S.T. Cracking the Code of Biodiversity Responses to Past Climate Change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselt, I.; Heinze, T. Rain, Snow and Frozen Soil: Open Questions from a Porescale Perspective with Implications for Geohazards. Geosciences 2021, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.M.; Berdugo, M.; Saez-Sandino, T.; Tao, D.; Ren, T.; Zhou, G.; Liu, Y.R.; Terrer, C.; Reich, P.B.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Temperature thresholds induce abrupt shifts in biodiversity and ecosystem services in montane ecosystems worldwide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2413981122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglis, J. Grief, Grit, and Gratitude: Finding Resilience in the Face of Climate Change. In From Environmental Loss to Resistance; Loadenthal, M., Rekow, L., Eds.; University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosh, S.M.; Ryan, R.; Fallander, K.; Robinson, K.; Tognela, J.; Tully, P.J.; Lykins, A.D. The relationship between climate change and mental health: A systematic review of the association between eco-anxiety, psychological distress, and symptoms of major affective disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrance, E.L.; Thompson, R.; Le Newberry Vay, J.; Page, L.; Jennings, N. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence, and its Implications. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2022, 34, 443–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Climate Grief: How We Mourn a Changing Planet. BBC. 3 April 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200402-climate-grief-mourning-loss-due-to-climate-change (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comtesse, H.; Ertl, V.; Hengst, S.M.C.; Rosner, R.; Smid, G.E. Ecological Grief as a Response to Environmental Change: A Mental Health Risk or Functional Response? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, J. The Psychology of Climate Anxiety. BJPsych Bull. 2021, 45, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, H.; Olson, J.; Paul, P. Eco-anxiety in youth: An integrative literature review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 633–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, M.; Redican, E.; Shevlin, M.; Nolan, E. Psychometric assessment of climate-related emotional responses: A systematic review of measures for eco-anxiety and related constructs. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 4883–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselt, I. Climate Change Adaptation in the Alpine Territories: Risk Perception, Obstacles and Adaptation Strategies. In Proceedings of the Interpraevent 2024—Conference Proceedings, Vienna, Austria, 10–13 June 2024; pp. 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver, J.S. Climate Change Adaptation: Civil and Environmental Engineering Challenge. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 01820001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, E.L.F.; Maharaj, S.S.; Pecl, G.T. Scientists have emotional responses to climate change too. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 1010–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naustdalslid, J. Climate change–the challenge of translating scientific knowledge into action. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2011, 18, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, S. Knowledge for a just climate. Clim. Chang. 2021, 169, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Haunschild, R.; Boyack, K.; Marx, W.; Minx, J.C. How relevant is climate change research for climate change policy? An empirical analysis based on Overton data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N. The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal. Off. Publ. Soc. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, A.; Ariccio, S.; de Dominicis, S.; Cancellieri, U.G.; Petruccelli, I.; Ilin, C.; Bonaiuto, M. The better the bond, the better we cope. The effects of place attachment intensity and place attachment styles on the link between perception of risk and emotional and behavioral coping. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnelli, F.; Pedoth, L. Enhancing risk governance by addressing key risk communication barriers during the prevention and preparedness phase in South Tyrol (Italy). Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1538–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Massazza, A.; Akhter-Khan, S.C.; Wray, B.; Husain, M.I.; Lawrance, E.L. Mental health and psychosocial interventions in the context of climate change: A scoping review. npj Ment. Health Res. 2024, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlatter, L.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, P. Climate Change and Mental Health Nexus in National Climate Policy-Gaps and Challenges. Ann. Glob. Health 2025, 91, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying, 1st ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, K.J. Grief Is a Journey: Finding Your Path Through Loss; Atria Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Running, S.W. The 5 Stages of Climate Grief. Available online: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/ntsg_pubs/173 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, E.; Wüstenhagen, R. Leading Organizations Through the Stages of Grief. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 186–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H. The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement: Rationale and Description. Death Stud. 1999, 23, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O.; Rohrmann, B. Cross-Cultural Risk Perception: State and Challenges. In Cross-Cultural Risk Perception; Renn, O., Rohrmann, B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change, 1st ed.; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jikybebna. Kübler-Ross Grieving Curve (Edited). Own Work; Licensed Under CC BY-SA 4.0. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International. 2021. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:K%C3%BCbler_Ross_grieving_curve_(edited).svg (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Norgaard, K.M. Climate Denial: Emotion, Psychology, Culture, and Political Economy: Chapter 27. In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society; Dryzek, J.S., Norgaard, R.B., Schlosberg, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, C.D. The Concentration and Isotopic Abundances of Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere. Tellus 1960, 12, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weart, S.R. The Discovery of Global Warming: Revised and Expanded Edition; New Histories of Science, Technology, and Medicine Series; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Oreskes, N.; Risbey, J.S.; Newell, B.R.; Smithson, M. Seepage: Climate change denial and its effect on the scientific community. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farman, J.C.; Gardiner, B.G.; Shanklin, J.D. Large losses of total ozone in Antarctica reveal seasonal ClOx/NOx interaction. Nature 1985, 315, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, R.P. What Can Be Learned from DuPont and the Freon Ban: A Case Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 40, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parson, E. Protecting the Ozone Layer: Science and Strategy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, E.M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA; Berlin, Germany; London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frumhoff, P.C.; Heede, R.; Oreskes, N. The climate responsibilities of industrial carbon producers. Clim. Chang. 2015, 132, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supran, G.; Oreskes, N. Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications (1977–2014). Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 084019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, W.F.; Mattioli, G.; Levi, S.; Roberts, J.T.; Capstick, S.; Creutzig, F.; Minx, J.C.; Müller-Hansen, F.; Culhane, T.; Steinberger, J.K. Discourses of climate delay. Glob. Sustain. 2020, 3, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Sustainability. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliacci, F.; Defrancesco, E.; Bettella, F.; D’Agostino, V. Mitigation of Urban Pluvial Flooding: What Drives Residents’ Willingness to Implement Green or Grey Stormwater Infrastructures on Their Property? Water 2020, 12, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choon, S.W.; Ong, H.B.; Tan, S.H. Does risk perception limit the climate change mitigation behaviors? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1891–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedoth, L.; Stawinoga, A.E.; Thaler, T.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Carnelli, F.; Damyanovic, D. Impacts of hazard maps on individual reaction? Results from a case study in South Tyrol, Italy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 130, 105803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, L.S.; Paivio, S.C. Working with Emotions in Psychotherapy; The Practicing Professional; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, S.C. Getting real about it: Navigating the psychological and social demands of a world in distress. In Environmental Leadership: A Reference Handbook; Gallagher, D.R., Ed.; The SAGE Reference Series on Leadership; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 2012; pp. 432–440. [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen, T.; Andersen, G.; Tvinnereim, E. The strength and content of climate anger. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2023, 82, 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, L.N.; Jordan, G.; Berglund, F.; Holden, B.; Niehoff, E.; Pohl, F.; Younssi, M.; Zevallos, I.; Ágoston, C.; Varga, A.; et al. Acting as we feel: Which emotional responses to the climate crisis motivate climate action. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 96, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehleb, R.I.; Kallis, G.; Zografos, C. A discourse analysis of yellow-vest resistance against carbon taxes. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2021, 40, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, D. Coal Mine Protests in Germany and Poland Highlight Phase-Out Challenges. 2020. Available online: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/coal-mine-protests-germany-and-poland-highlight-phase-out-challenges (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Via AP News Wire. Polish miners, power workers, protest shift away from coal Solidarity Czech Republic Prague Warsaw European Union. The Independent, 9 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, T.; Sander, H.; Fünfgeld, A.; Mey, F. Climate obstruction at work: Right-wing populism and the German heating law. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 123, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukirch, M. Grinding the grid: Contextualizing protest networks against energy transmission projects in Southern Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, A.; Smith, M. How Local Opposition Can Thwart Renewable Energy Projects. POWER Magazine, 1 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Foehringer Merchant, E. Community Opposition and Grid Challenges Slow the Pace of Renewable Efforts, National Survey of Developers Shows. Inside Climate News. 23 February 2024. Available online: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/23022024/community-opposition-and-grid-challenges-slow-pace-of-renewable-efforts/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- EHN Curators. Europe’s renewable energy growth faces backlash as communities demand more benefits and engagement. Environmental Health News, 7 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, C. Why Greta Thunberg and Other Climate Activists Are Protesting Wind Farms in Norway. Time, 28 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Töller, A.E.; Garske, B.; Rasch, D.; Weigel, A.; Hahn, H. Failing successfully? Local referendums and ENGOs’ lawsuits as challenges to wind energy expansion in Germany. Z. Vgl. Polit. 2024, 18, 273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polczer, S. Alberta communities unite in grassroots protest against solar farms. Western Standard, 17 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- The Brussels Times with Belga. Associations call for a moratorium on wind and solar farms in the EU. The Brussels Times, 4 June 2025. Available online: https://www.brusselstimes.com/1611672/associations-call-for-a-moratorium-on-wind-and-solar-farms-in-the-eu (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Cain, N.L.; Nelson, H.T. What drives opposition to high-voltage transmission lines? Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Big Bad Biomass International Action: Protests in Indonesia against Biomass Co-Firing. Trend Asia, 21 October 2022.

- Bower, A. Community members protest planned biofuel plant near Peace Arch border. CityNews Vancouver, 30 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Protest against ethanol plant turns violent in Gadwal. Times of India, 5 June 2025.

- Wetzels, H. How a Nitrogen Crisis Turned Dutch Farmers to Rage. ARC2020, 12 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Darroch, G. Farmers to stage new protest against nitrogen plans on October 16. DutchNews. 7 October 2019. Available online: https://www.dutchnews.nl/2019/10/farmers-to-stage-new-protest-against-nitrogen-plans-on-october-16/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A. What Is Climate Grief? 2019. Available online: www.climateandmind.org/what-is-climate-grief (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Hamilton, J. “Alchemizing Sorrow Into Deep Determination”: Emotional Reflexivity and Climate Change Engagement. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 786631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J. Overcoming the ‘value–action gap’ in environmental policy: Tensions between national policy and local experience. Local Environ. 1999, 4, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Kweh, Q.L.; Goh, K.W.; Wider, W. Redefining marketing strategies through sustainability: Influencing consumer behavior in the circular economy: A systematic review and future research roadmap. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 18, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N. Addressing scandals and greenwashing in carbon offset markets: A framework for reform. Glob. Transitions 2025, 7, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Márquez, A.J.; González-González, J.M.; Zamora-Ramírez, C. An international empirical study of greenwashing and voluntary carbon disclosure. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, N.; Probst, B. The negligible role of carbon offsetting in corporate climate strategies. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Fu, W.; Guo, P.; Zhang, Z.; Khan, F. Unpacking greenwashing: The impact of environmental attitude, proactive strategies, and network embeddedness on corporate environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiyo, B.; Field, C.B. Embracing imperfection: Carbon offset markets must learn to mitigate the risk of overcrediting. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4, pgaf091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, A. Carbon Credit Caution: Lessons from Kenya’s Offset Controversy. FurtherAfrica, 6 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Biogradlija, A. Carbon Offsets in Kenya: Scrutiny Over Conservation, Community Rights, and Profit Distribution. EnergyNews. 13 January 2025. Available online: https://energynews.biz/carbon-offsets-in-kenya-scrutiny-over-conservation-community-rights-and-profit-distribution/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Cisneros, E.; Kis-Katos, K.; Nuryartono, N. Palm oil and the politics of deforestation in Indonesia. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 108, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfgott, A.; Midgley, G.; Chaudhury, A.; Vervoort, J.; Sova, C.; Ryan, A. Multi-level participation in integrative, systemic planning: The case of climate adaptation in Ghana. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 309, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulis, E.; Pilet, J.B.; Vittori, D.; Rojon, S. When climate assemblies call for stringent climate mitigation policies: Unlocking public acceptance or fighting a losing battle? Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 171, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Loorbach, D.; Meadowcroft, J. Governing societal transitions to sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M. Empowering Actors in Transition Management in and for Cities. In Co-creating Sustainable Urban Futures; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11, pp. 131–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reianu, D.G.; Dobra, D.M. Digital Public Consultation and the Opportunities for Participatory Democracy: An Exploratory Study. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabria, L.; Marks, E. A scoping review of the impact of eco-distress and coping with distress on the mental health experiences of climate scientists. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1351428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihkala, P. Klimakummer, Klimadepression und Solastalgie. In Climate Emotions: Klimakrise und Psychische Gesundheit; Psychosozial-Verlag: Gießen, Germany, 2022; pp. 97–128. Available online: https://researchportal.helsinki.fi/en/publications/klimakummer-klimadepression-und-solastalgie (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, M.; Gal-Oz, R.; Safer, D.L. Community-Based Resilience: The Influence of Collective Efficacy and Positive Deviance on Climate Change-Related Mental Health. In Storytelling to Accelerate Climate Solutions; Coren, E., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.; Blashki, G.; Wiseman, J.; Burke, S.; Reifels, L. Climate change and mental health: Risks, impacts and priority actions. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, T.; Costa, J.; Santos, O.; Sousa, J.; Ribeiro, T.; Freire, E. Evidence on the contribution of community gardens to promote physical and mental health and well-being of non-institutionalized individuals: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, C.; Grieger, J.A.; Kalamkarian, A.; D’Onise, K.; Smithers, L.G. Community gardens and their effects on diet, health, psychosocial and community outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellehumeur, C.R.; Carignan, L.M.; Robinson, N. Acceptance and commitment therapy to alleviate climate-induced psychological distress. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, B.; Swart, R.; Marinova, N.; van Hove, B.; Jacobs, C.; Klostermann, J.; Kazmierczak, A.; Peltonen, L.; Kopperoinen, L.; Oinonen, K.; et al. Urban Adaptation to Climate Change in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities for Cities Together with Supportive National and European Policies; EEA Report; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- ClimaSTORY—l’Adaptation au Changement Climatique. Available online: https://climastory.fr/ (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Bokhove, O.; Hicks, T.; Zweers, W.; Kent, T. Wetropolis extreme rainfall and flood demonstrator: From mathematical design to outreach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 2483–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselt, I.; Großmann, L.; Rieger, W. Naturgefahrenmodelle—Interaktive Tools für eine erfolgreiche Risikokommunikation. Wildbach- Lawinen- Eros.- Steinschlagschutz 2023, 87, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sermet, Y.; Demir, I. Virtual and augmented reality applications for environmental science education and training: Chapter 17. In New Perspectives on Virtual and Augmented Reality; Daniela, L., Ed.; Perspectives on Education in the Digital Age; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselt, I. Study of Physical Natural Hazard Models: Final Report: Technical Report. Available online: https://www.capa-eusalp.eu (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Bär, C.; Johnsen, L.; Gölz, S. Potenzial von Serious Games als Instrument zur Beförderung von Nachhaltigkeit: Eine Betrachtung aus Sicht des Umweltbundesamtes: UBA TEXTE 80/2023. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/potenzial-von-serious-games-als-instrument-zur (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- HQ50 Serious Game: Hochwasser in Ihrer Gemeinde! 2024. Available online: https://howapro.de/howa-hq50-game/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Wachinger, G.; Renn, O.; Begg, C.; Kuhlicke, C. The risk perception paradox–implications for governance and communication of natural hazards. Risk Anal. Off. Publ. Soc. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, B.R.; Star, C.; Leal Filho, W. Effectiveness of the Local Adaptation Plan of Action to support climate change adaptation in Nepal. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2016, 21, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizikova, L.; Pinter, L.; Tubiello, F.N. Recent Progress in Applying Participatory Scenario Development in Climate Change Adaptation in Developing Countries. Part II. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/participatory-scenario-development-climate-change-adaptation-part-ii.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Wolff, E.; French, M.; Ilhamsyah, N.; Sawailau, M.J.; Ramírez-Lovering, D. Collaborating With Communities: Citizen Science Flood Monitoring in Urban Informal Settlements. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteaw, B.O.; Amoah, A.B.; Boadi, J.; Awuah, P.; Dorcoo, S. Accelerating climate action through increased knowledge: Transitional learning innovations for subnational adaptation planning in Ghana. Soc. Impacts 2025, 6, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, R.; Bruine de Bruin, W.; Dessai, S.; Taylor, A. Envisioning Climate Change Adaptation Futures Using Storytelling Workshops. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Cabeza, M. Indigenous Storytelling and Climate Change Adaptation. In Resilience Through Knowledge Co-Production; Roué, M., Nakashima, D., Krupnik, I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, C.; Norris, K. Climate change and mental health: Postgraduate psychology student and program coordinator perspectives from Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Aust. Psychol. 2024, 59, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grief Stage | Prevailing Barrier | Message Framing Cue | Participatory Lever | Indicator of Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denial | Psychological distancing, minimisation of risk | “These changes affect our community now.” | Localised education, infographics, serious games | Willingness to acknowledge local climate impacts |

| Anger | Distrust, blame, perceived unfairness | “Your frustration is valid. Let’s talk about just solutions.” | Structured dialogue forums, climate assemblies | Initial openness to hear opposing views or collaborate |

| Pessimistic Bargaining | Overwhelm, disengagement, symbolic actions | “Small steps matter, but we must act meaningfully together.” | Low-threshold involvement (e.g., idea boxes, surveys, consultations) | Participation in small-scale or token efforts |

| Depression | Powerlessness, grief, withdrawal | “You’re not alone. Together we can make a difference.” | Community-building, peer support, creative formats | Renewed interest in group activity or shared emotional expression |

| Optimistic Bargaining | Strategic avoidance of deeper change | “These actions are a step forward, How can we do more?” | Co-creation workshops, feedback loops, deliberative processes | Proactive suggestions or demand for deeper, systemic engagement |

| Acceptance | Emotional fatigue, residual uncertainty | “Adaptation is possible. Here’s how we already succeed.” | Institutional commitment, scenario planning, youth leadership | Integration of adaptation into strategies, policies, or long-term vision |

| No. | Recommendation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Frame Climate Change with Local Relevance | Highlight tangible climate and weather impacts that resonate with local experiences, and frame adaptation measures through their co-benefits, such as improved infrastructure, job creation, and public well-being. |

| 2. | Acknowledge and Support Emotional Responses | Recognise emotions such as grief, anxiety, and frustration as valid reactions. Integrate emotional literacy and mental health resources into climate strategies, including peer support and safe spaces for open dialogue. |

| 3. | Engage Diverse and Trusted Voices | Tailor communication to different cultural and social contexts, involving under-represented groups, and collaborate with trusted community figures to counter misinformation, strengthen credibility, and increase relevance. |

| 4. | Bridge Psychological Distance | Use relatable narratives and local examples to connect abstract climate science with everyday life, reducing denial and disengagement. |

| 5. | Empower Constructive Engagement | Channel emotional responses into action by enabling participatory forums, co-creation of solutions, and citizen-led contributions to policy. |

| 6. | Encourage Realistic and Inclusive Change | Promote practical behavioural shifts framed as “win-win” actions and emphasise their contribution to broader systemic change. |

| 7. | Foster Hope and Long-Term Resilience | Present climate change as solvable. Support education, citizen science, and intergenerational dialogue to build shared purpose, agency, and emotional resilience. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baselt, I.; Erber, S.; Monnet, L.; Berger, F.; Carnelli, F.; Pedoth, L.; Moro, A.; Bazzan, E.; Bonilla, R. From Denial to Acceptance—Leveraging the Five Stages of Grief to Unlock Climate Action. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198929

Baselt I, Erber S, Monnet L, Berger F, Carnelli F, Pedoth L, Moro A, Bazzan E, Bonilla R. From Denial to Acceptance—Leveraging the Five Stages of Grief to Unlock Climate Action. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198929

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaselt, Ivo, Sabine Erber, Laurence Monnet, Frédéric Berger, Fabio Carnelli, Lydia Pedoth, Andrea Moro, Elena Bazzan, and Rogelio Bonilla. 2025. "From Denial to Acceptance—Leveraging the Five Stages of Grief to Unlock Climate Action" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198929

APA StyleBaselt, I., Erber, S., Monnet, L., Berger, F., Carnelli, F., Pedoth, L., Moro, A., Bazzan, E., & Bonilla, R. (2025). From Denial to Acceptance—Leveraging the Five Stages of Grief to Unlock Climate Action. Sustainability, 17(19), 8929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198929