Sustainable Fashion in Slovenia: Circular Economy Strategies, Design Processes, and Regional Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Scale and contextual biases persist as sustainability solutions developed for multinational companies are poorly tested in SMEs within transitional economies.

- Post-socialist sustainability trajectories remain underexplored compared to established fashion economies, leaving critical gaps in comparative analysis.

- Cultural heritage is insufficiently integrated into sustainability frameworks, limiting the potential of traditional knowledge for innovative solutions.

- Community engagement in small-scale fashion contexts is insufficiently addressed despite its increasing recognition as a key sustainability strategy.

- Design innovations (zero-/low-waste techniques, modularity, upcycling),

- Production sustainability (energy and water efficiency, local/regional sourcing),

- Dematerialization approaches (leasing, repair, co-creation models),

- Digital engagement (transparency, traceability, advocacy),

- Cultural engagement (revival of traditional craftsmanship, DIY culture).

2. Research Design

- Explicitly reference or demonstrate sustainability in design, production, communication or community engagement; and

- Present collections at fashion events consistently over a number of years to ensure sustained activity rather than short-term initiatives.

- Participant observation at 15 industry events (fashion shows, exhibitions, stakeholder meetings and talks, and sustainability workshops) which allowed for first-hand documentation of sustainability practices and discursive trends.

- Semi-structured interviews with 24 participants (18 designers and brand representatives, 1 producer and 5 media actors). Interviews were recorded where permitted (n = 20) and otherwise documented through detailed notes and immediate post-conversation write ups (n = 24).

- Archival and literature review encompassed materials spanning from 1954 to 2024, including trade reports, policy documents and historical analyses of the Slovenian textile and apparel sector.

- 1.

- Qualitative thematic analysis:

- Interview transcripts, observation notes, and archival materials were coded following Braun & Clarke’s [8] reflexive thematic analysis approach.

- Codes were developed inductively and then refined into categories such as waste reduction, supply chain localization, design innovation, cultural engagement and digital transparency.

- The intersection of three approaches—interviews, observation and media sources—ensures validity and reduces reliance on self-reporting.

- 2.

- Quantitative description mapping:

- Practices were recorded for each of the 52 brands.

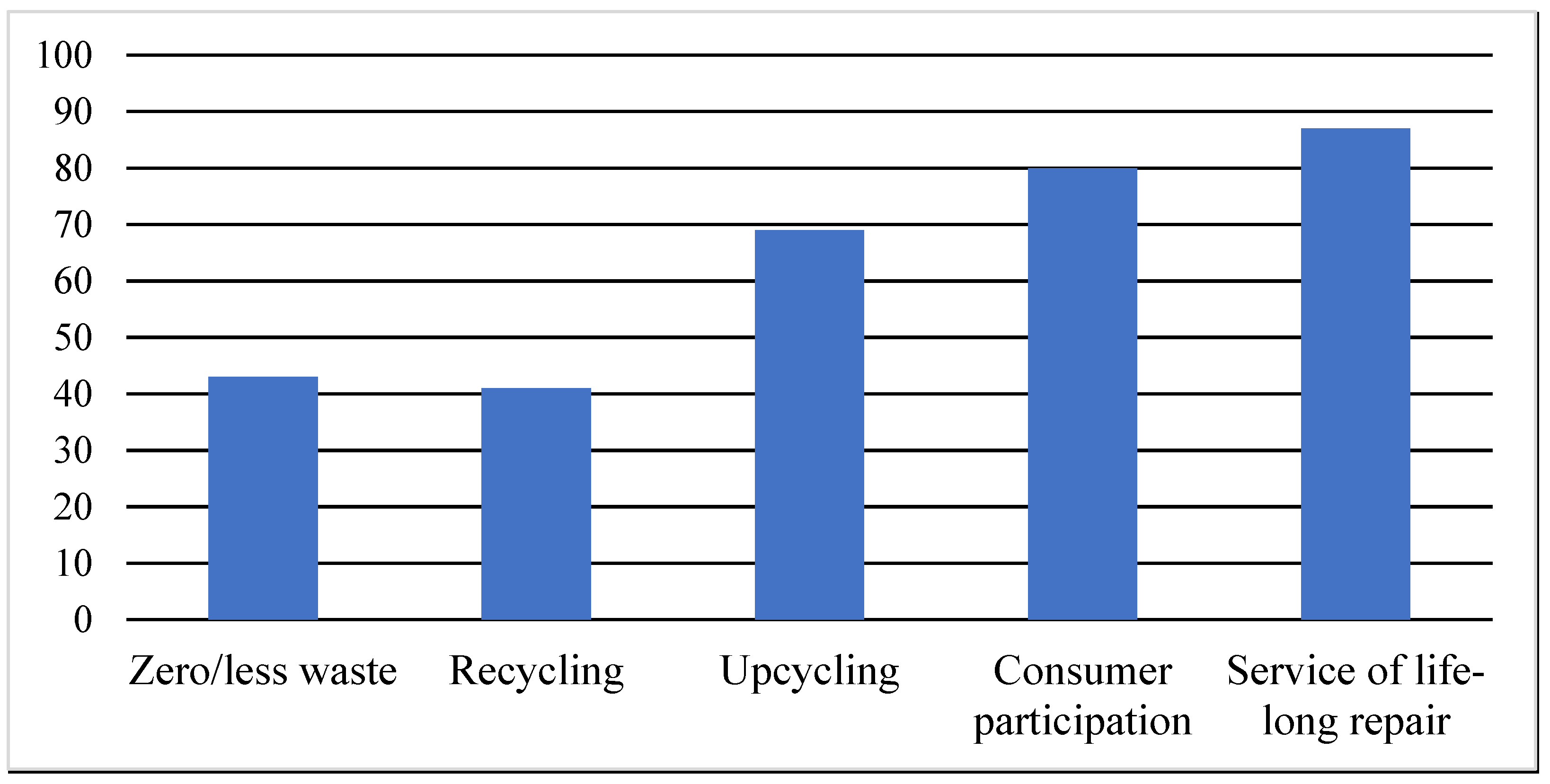

- The results showed that 69% employed some form of upcycling, 87% offered repair or alteration services, 41% integrated zero- or less-waste tailoring and 40% actively revived traditional craft techniques.

- These statistics provided a baseline for assessing the prevalence and diversity of sustainability strategies in Slovenia’s fashion sector.

3. Sustainability Concepts of Slovenian Fashion Brands in the Socialist and Post-Socialist Periods

3.1. Historical Sustainability-Oriented Foundations of Slovenian Fashion: A Legacy for Contemporary Practices

3.2. Current Practices: Analysis of Contemporary Sustainability-Oriented Slovenian Fashion

- Zero-waste or reduced-waste tailoring, emphasizing pattern efficiency and material optimization;

- Recycling and upcycling, with a particular focus on how existing garments are reintroduced into circulation;

- Design for adaptability and longevity, involving modularity, repairability, and continuous product improvement;

- Consumer participation in the design process, highlighting co-creation as a means of extending product value;

- Digital engagement through social media, used both as an educational tool for sustainable fashion and as a platform for sharing brand narratives;

- Community-building practices where brands initiate and foster fashion communities around sustainability values;

- Repair services, offered as lifelong product support to slow down fashion consumption and counteract the prevailing ‘clothing metabolism’ [4] (p. 89).

4. Contemporary Sustainability-Oriented Fashion Identity in Slovenia

4.1. Sustainable Fashion Practices in Slovenia

4.2. Strategic Opportunities for Local Production

4.3. The Role of Craftsmanship and Cultural Heritage

5. Discussion

5.1. Strategic Vision for Slovenian Sustainable Fashion

- Institutional leadership: Establishment of a professional chamber, or governing body to serve as the custodian of the sector’s vision in fulfilling sustainability strategies. This organization should foster cross-sectoral collaboration across policy makers, educational institutions, designers and entrepreneurs.

- Digital platforms: Developing a comprehensive platform for Slovenian fashion brands with clear sustainability strategies, intended for presentations, promotion and education.

- Promotion and market positioning: Strengthening both domestic and international promotion of Slovenian sustainability-oriented fashion brands. The emphasis should be on niche, sustainably focused production to increase market differentiation. The label ‘Made in Slovenia’ could include a segment dedicated to sustainable fashion, thereby reinforcing cultural authenticity and sustainable value.

- Sustainability and heritage integration: Preservation and innovation in traditional handicrafts, linking heritage techniques with sustainable practices such as zero-waste design, natural dyeing and the use of locally sourced materials. A hybrid integration of craft and modern technology can create high-value, export-oriented products.

- Circular economy theory: Craft-based micro-production supports circularity with local sources, minimal waste and short supply chains.

- Post-socialist transition insights: Fashion, whose development has been influenced by economic, political and social changes, struggles with small-scale production, restrictions on the global market and structural obstacles in transition economies.

- Cultural heritage preservation theory: It emphasizes the importance of incorporating and developing handicraft skills in the preservation of intangible cultural assets while also linking heritage preservation with economic and environmental sustainability outcomes.

- Policy recommendations: Priority should be placed on supporting cooperative production hubs and providing targeted grants to strengthen small-scale textile manufacturing. Financial support for sustainable artisanal innovation needs to be further developed and sustainability certification schemes should be developed to ensure cultural sustainability and authenticity.

- Industry guidelines: Hybrid integration of craft and technology, collaborative production models and transparency through the use of digital tools should be promoted to increase efficiency and competitiveness in the market.

- Impact on education: Curricula that combine traditional craft skills with sustainable design principles should be developed for the education of future fashion designers.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

- Conduct studies to monitor changes in the implementation of sustainable practices or strategies over time.

- Undertake cross-national comparisons with other post-socialist transitional and small-scale fashion systems.

- Explore digital platforms to preserve artisanal heritage, increase transparency and develop a sustainable fashion identity.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sdgs.un.org. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- McCracken, G. Culture and Consumption: A Theoretical Account of Structure and Movement of the Cultural Meaning of Consumer Goods. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion & Sustainability: Fashion for Change; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Design, when Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Statista.com. Number of Enterprises in the Manufacturing of Wearing Apparel Sector in Slovenia from 2021 to 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/369990/number-of-enterprises-in-the-manufacturing-of-wearing-apparel-sector-in-slovenia/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Centre for Creativity. Sektor Mode v Sloveniji. In Proceedings of the Focus Group Workshop on Fashion, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 17 April 2025; Centre for Creativity: Ljubljana, Slovenia. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clark, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psycology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terdiman, R. Present Past: Modernity and the Memory Crisis; Cornell University Press: Ithaca: NY, USA; London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Oblak Japelj, N. Knjižnica Industrije usnja Vrhnika:pridobitev domoznanske zbirke Cankarjeve knjižnice Vrhnike. In Proceedings of the Usnjarstvo na Slovenskem, Šoštanj, Slovenia, 23 September 2013; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Podbevšek, A. Nihče nam ne gleda pod prste. Jana 1983, 23, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kobe Arzenšek, K. Pletenina: Tovarna Trikotažnega Perila: Zgodovinski Zapis ob Trojnem Jubileju; Pletenina, tovarna trikotažnega perila Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ladika, N. Problematika tekstilne industrije. Vezilo 1975, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Babič, K.; Dabič Perica, S. Brazde.org. Aplikativna Analiza Stanja na Področju Socialne Ekonomije v Republiki Sloveniji. 2018. Available online: http://brazde.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Analiza-stanja-na-podro%C4%8Dju-socialne-ekonomije-v-Sloveniji.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Coscieme, L.; Manshoven, S.; Gillabel, J.; Grossi, F.; Mortensen, L.F. A Framework of circular business models for fashion and textiles: The role of business-model, technical, and social innovation. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista.com. Apparel-Slovenia. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/apparel/slovenia (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Celcar, D. Trajnost in tehnologija v modni industriji. In Preteklost Oblikuje Sedanjost: Zbornik ob Razstavi Alpska Modna Industrija Almira-Preteklost Oblikuje Sedanjost; Devetak, T., Ed.; Muzeji Radovljiške Občine: Radovljica, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vivrebypetrajeric.com. Available online: https://www.vivrebypetrajeric.com/about-3 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Lužovec, I.; Kokol, L. Srednjeročni Program Razvoja Tekstilne Industrije SR Slovenije 1976–1980: D.3.–Ekonomski del; Tekstilni Inštitut: Ljubljana, Slovenija, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Eržen, S. Shirting. Mladina 2016, 32, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, A. Vestoj.com. Decolonizing Fashion: Defying the ‘White Man’s Gaze’. Available online: http://vestoj.com/decolonialising-fashion/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Cater, L. Politico.com. Brussels Turns to ‘Artisanal Skills’ to Mend the Textile Industry. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/brussels-artisanal-skills-mend-textiles-industry-europe-fast-fashion/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Stupica, M. Naša tekstilna industrija. Maneken 1957, 2, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Von Busch, O. Fashion-Able: Hactivism and Engaged Fashion Design. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg: School of Design and Craft (HDK), Gotheburg, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gaberščik, V. Odprte Glave 2/III–Vesna Gaberščik 16. 11. 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=02_uF2Vr71c (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Blejski pušeljc v Tekstilindusovih oblekah. Jana 1979, 21, 7.

- Anselma.si. Available online: https://anselma.si/about (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Britovšek, S. Večer.com. Mariborska Ustvarjalka Tina Princ: Česar ne Najde, kar Pogreš, Tisto Ustvari. Available online: https://vecer.com/v-nedeljo/mariborska-ustvarjalka-tina-princ-cesar-ne-najde-kar-pogresa-tisto-ustvari-10236259 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Czk.si. Available online: https://czk.si/priloznosti/vili-van-style-odprti-poziv-za-vse-mlade-blagovne-znamke/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Hishka.com. Available online: https://hishka.com/about/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Big See.eu. Available online: https://bigsee.eu/sewists-appetite/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- D’Itria, E.; Aus, R. Circular fashion: Evolving practices in a changing industry. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2023, 19, 2220592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernejčič Dolinar, B.; Bojnec, Š. Dynamics of Enterprises and Employees in the Slovenian Textile Industry in the period from 1995 to 2017. Tekstilec 2022, 65, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pub. norden.org. Post-Consumer Textile Circularity in the Baltic Countries: Current Status and Recommendations for the Future. Available online: https://pub.norden.org/temanord2020-526/# (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Polajnar Horvat, K.; Šrimpf Vendramin, K. Issues Surrounding Behavior towards Descarded Textiles and Garments in Ljubljana. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Craft of Use: Post-Growth Fashion; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

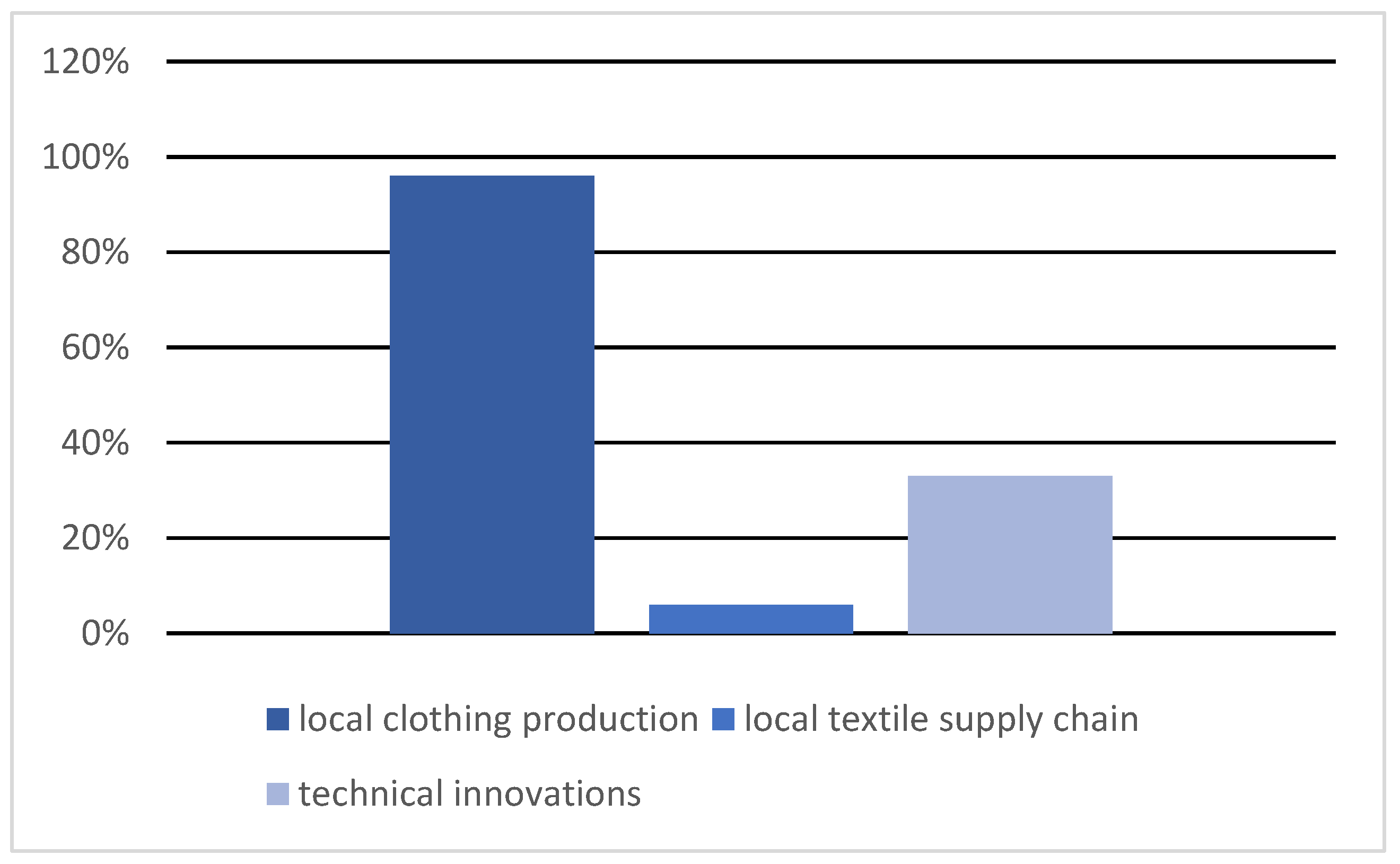

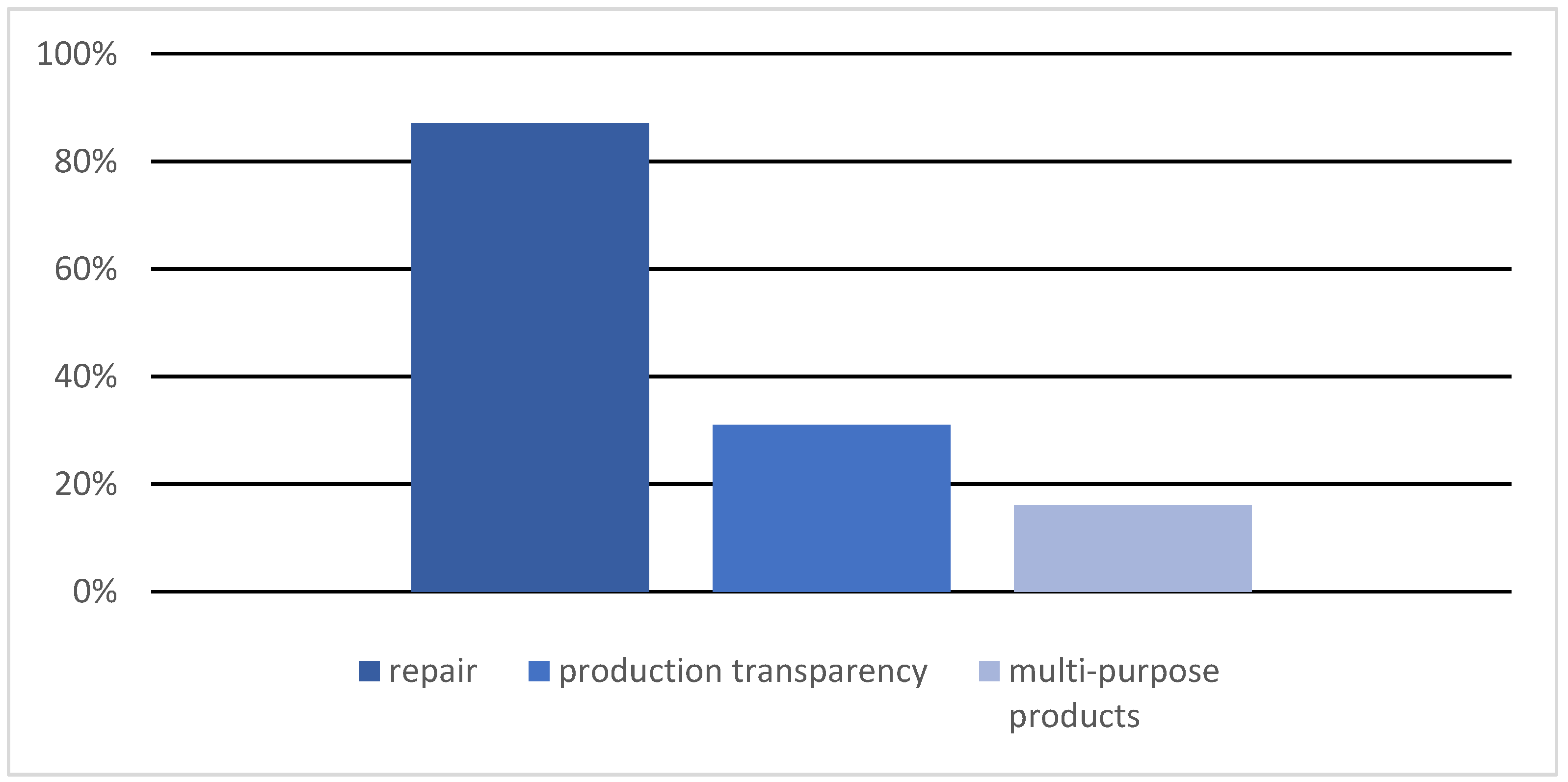

| Sustainable Practice | Adoption Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Product life-long repairs | 87% | Strong alignment with circular economy principles. |

| Consumer participation and repair/upcycling | 80% | Builds community engagement. |

| Zero- or low-waste design | 47% | Move closer to sustainable fashion production. |

| Use of locally produced textiles | 6% | Major supply chain gap. |

| Local garment production | 96% | Strong asset for transparency and traceability. |

| Publicly verifiable accurate production data | 31% | Indicates low transparency adoption. |

| Technique | Share of Brands (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Knitting | 13 | Associated with historical use, but underexploited in volume and export. |

| Handmade Screen Printing | 13 | Used in small batches, in artisanal environments. |

| Embroidery | 5 | Historically significant but currently rare. |

| Other Crafts (e.g., weaving, felting) | Minimal | Initiatives aimed at promoting local flax cultivation and small-scale production of woven textiles. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Devetak, T.; Pavko Čuden, A. Sustainable Fashion in Slovenia: Circular Economy Strategies, Design Processes, and Regional Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198890

Devetak T, Pavko Čuden A. Sustainable Fashion in Slovenia: Circular Economy Strategies, Design Processes, and Regional Innovation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198890

Chicago/Turabian StyleDevetak, Tanja, and Alenka Pavko Čuden. 2025. "Sustainable Fashion in Slovenia: Circular Economy Strategies, Design Processes, and Regional Innovation" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198890

APA StyleDevetak, T., & Pavko Čuden, A. (2025). Sustainable Fashion in Slovenia: Circular Economy Strategies, Design Processes, and Regional Innovation. Sustainability, 17(19), 8890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198890