1. Introduction

Greenwashing, defined as corporate practices of creating a positive environmental image through false or exaggerated claims to cover up inadequate actual environmental performance, has emerged as a critical strategy for firms to cope with mounting sustainability pressures and gain environmental legitimacy. Against the backdrop of global deepening inter-firm connectivity, the influencing factors and consequences of corporate environmental practices are now transcending organizational boundaries and extending across industrial chains. In response to this phenomenon, scholarly research on greenwashing has expanded beyond firm-level analyses to encompass network-level perspectives, examining how supply chain network centrality influences corporate greenwashing behavior [

1], strategic interactions among nodal firms in industrial chains [

2], and contagious effects within ESG investment frameworks [

3]. Emerging empirical evidence suggests potential inter-firm transmission mechanisms, including how customer firms’ environmental disclosure practices may unintentionally incentivize suppliers to engage in greenwashing behaviors [

4], while systematic literature reviews highlight growing scholarly recognition of the need for coordinated approaches to address environmental opportunism across supply chain networks [

5]. However, whether these patterns represent a fundamental transition from isolated misconduct to systematic coordination, and what governance mechanisms might effectively address such networked challenges, remains an open empirical question that requires further investigation. This emerging research landscape underscores the necessity of examining systematic greenwashing governance mechanisms that are compatible with the complex structure of industrial chains.

This global trend underscores the need for innovative governance mechanisms that can systematically address environmental externalities across complex production networks. Internationally, similar challenges have been approached through varied institutional arrangements. For instance, Germany’s “Industrie 4.0” initiative represents a comprehensive digitalization strategy involving coordinated efforts between government, industry, and research institutions to establish standards and foster collaboration within industrial value chains, though environmental considerations, while present as beneficial outcomes, are not its primary governance focus compared to manufacturing efficiency and digital transformation [

6]. Similarly, Japan’s historically influential practice of administrative guidance (gyosei shido) has demonstrated how government ministries can facilitate coordination with key industries to achieve strategic development objectives through informal yet systematic channels, embodying a form of embedded state facilitation [

7]. However, these models typically lack a dedicated governmental role with explicit mandate and administrative authority to coordinate entire industrial chains—from upstream suppliers to downstream distributors—specifically for mitigating systemic environmental risks such as greenwashing.

These limitations in existing international governance models underscore the need for alternative institutional arrangements capable of systematically addressing chain-level environmental opportunism. Against this backdrop, China’s Chain Leader Policy emerges as a theoretically and empirically significant case meriting rigorous investigation. Unlike the models discussed above, this policy represents a deliberate institutional innovation specifically designed to combat greenwashing through systematic industrial chain coordination. Since its initial implementation in Changsha in 2017, the policy has expanded across multiple Chinese cities, providing a natural experimental setting with sufficient temporal and geographical variation to enable robust causal inference. The policy’s scale and scope—encompassing diverse industries and thousands of enterprises across a 13-year observation window (2011–2023)—offer unprecedented opportunities to examine how embedded autonomy mechanisms operate in environmental governance contexts. This empirical setting addresses a critical gap in the literature; while existing studies have theorized about hybrid governance approaches, systematic evidence regarding their effectiveness in curbing corporate greenwashing remains limited. The Chain Leader Policy’s explicit environmental governance mandate, combined with its distinctive tri-level coordination architecture, positions it as an ideal case for investigating whether and how government-embedded coordination can transform greenwashing behaviors across industrial networks.

China’s ongoing exploration of the “Chain Leader Policy” provides valuable experience for researching effective industrial chain governance models. The Chain Leader Policy represents a fundamentally distinct governance innovation that differs markedly from existing international models in three critical dimensions. First, unlike Germany’s Industrie 4.0, which primarily focuses on digital transformation with environmental benefits as secondary outcomes, the Chain Leader Policy explicitly targets environmental governance as its core objective through systematic greenwashing mitigation. Second, whereas Japan’s administrative guidance (gyosei shido) operates through informal ministerial coordination, the Chain Leader mechanism establishes formal administrative authority with designated government officials who possess explicit mandates and resource allocation powers to coordinate entire industrial chains. Third, in contrast to market-based industry self-regulation prevalent in Western contexts, this policy embodies a hybrid governance approach that combines state administrative capacity with market coordination mechanisms, enabling systematic intervention across upstream–downstream networks specifically for environmental compliance. Unlike traditional top-down industrial policies, the Chain Leader Policy embodies an embedded autonomy mechanism. Under this framework, local government officials serve as chain leaders, leveraging their administrative guidance and resource coordination capabilities to promote deeper structural and functional integration of enterprises within the industrial chain network. This approach strengthens value and goal alignment, thereby activating the latent dynamics of the industrial chain system. Its functions are manifested in: guiding industrial chain development planning and resolving bottlenecks in upstream and downstream linkages; coordinating resources and demands among upstream and downstream firms, enterprises of varying sizes, academic and research institutions, and government departments to mitigate information asymmetry and collaboration barriers [

8]; integrating and optimizing the allocation of industrial chain resources to enhance overall efficiency and resilience [

9]; and providing tailored services to enterprises within the chain to accurately address common developmental challenges and bottlenecks [

10].

Enterprises do not exist as isolated entities but are embedded within multi-stakeholder interactive systems, which substantially increases the governance complexity of addressing greenwashing practices. For example, the convergence of direct greenwashing by enterprises at multiple supply chain levels and “substitutive greenwashing” such as supplier contract breaches results in blurred accountability boundaries and creates significant challenges for assigning responsibility [

11]. Furthermore, the high transaction costs associated with low-carbon technology diffusion and conflicts over the distribution of emission reduction benefits exacerbate enterprises’ green coordination dilemmas and expand the scope for “more talk, less action” opportunism [

12]. However, existing literature exhibits three critical limitations that constrain systematic understanding of greenwashing governance. First, mechanism specification deficit: current studies examine isolated greenwashing drivers [

13,

14,

15] but lack theoretical frameworks explaining how hybrid governance mechanisms systematically address greenwashing across industrial chains. Second, network-level analytical absence: research focuses on dyadic relationships [

1,

2] while overlooking how coordinated governance operates across multi-stakeholder networks to combat greenwashing. Third, institutional contingency gap: although institutional pressures influence environmental behavior [

16,

17], the ways different isomorphic pressures moderate hybrid governance effectiveness remain unexplored. These limitations result in fragmented approaches that cannot address greenwashing’s systemic nature in complex industrial networks.

This study addresses these limitations through three targeted innovations. Theoretically, we extend embedded autonomy theory to industrial chain environmental governance, providing the first systematic framework for dual-coordination mechanisms in greenwashing control. Empirically, we identify and validate four specific pathways through which hybrid governance reduces greenwashing—revealing the operational mechanisms behind policy effectiveness. Methodologically, we integrate institutional pressure theory to systematically examine how different isomorphic pressures moderate governance effectiveness, advancing beyond single-pressure approaches.

This study directly addresses the identified limitations through three distinct contributions that advance existing knowledge. First, we demonstrate how state-embedded coordination creates systematic anti-greenwashing effects that neither pure market mechanisms nor command-and-control approaches achieve, extending embedded autonomy theory to environmental governance contexts and resolving the mechanism specification deficit. Second, we provide empirical evidence of four specific pathways through which the Chain Leader Policy operates—supply–demand stabilization, coordination cost reduction, collaborative innovation, and external scrutiny—resolving the pathway identification absence and the “black box” problem in governance mechanism research. Third, we establish how institutional pressures systematically moderate hybrid governance effectiveness, revealing that coercive isomorphism strengthens while mimetic isomorphism weakens policy impact, addressing the institutional contingency oversight and providing actionable insights for context-sensitive governance design. Our large-scale quantitative analysis using 12,334 firm-year observations addresses the empirical validation gap through rigorous causal identification.

2. Literature Review

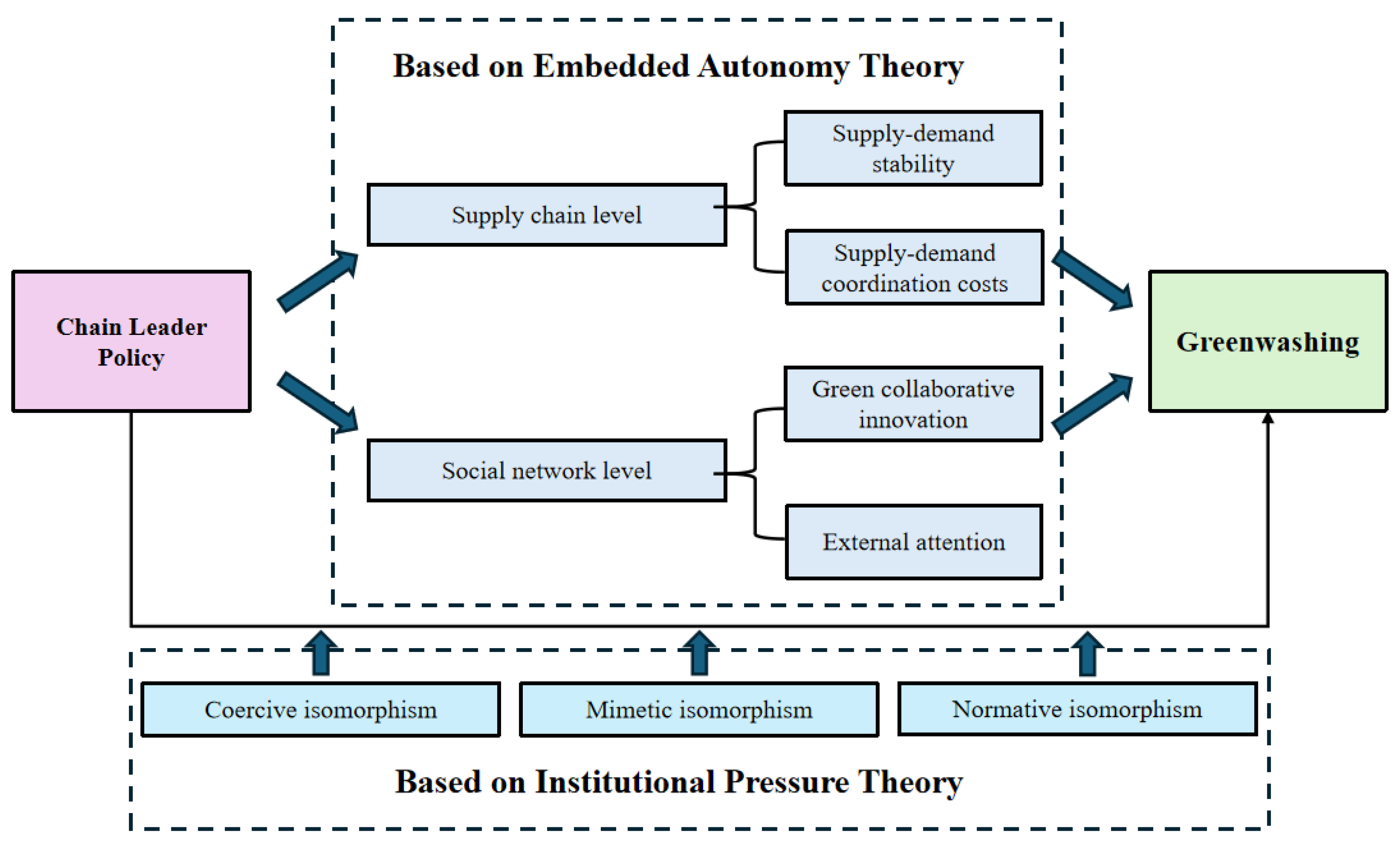

This study adopts a dual-theory integration framework to comprehensively analyze how the Chain Leader Policy influences corporate greenwashing behavior. Embedded autonomy theory serves as the primary theoretical foundation for explaining the policy’s mediating mechanisms—specifically, how government officials, as chain leaders, leverage their embedded position within socio-economic networks to coordinate supply chain relationships and mobilize social network resources, thereby systematically addressing greenwashing practices. Institutional pressure theory complements this framework by explaining the moderating mechanisms—how different types of isomorphic pressures (coercive, mimetic, and normative) from the external institutional environment shape the effectiveness of the Chain Leader Policy. This theoretical integration enables a more nuanced understanding of hybrid governance mechanisms in environmental governance, addressing both the internal coordination logic and external institutional conditions that determine policy effectiveness.

2.1. Theoretical Foundation: Embedded Autonomy Theory

Embedded autonomy theory represents an extension of embeddedness theory [

18] into the realm of governance. Evans [

19] pioneered its development through the core concept of “embedded autonomy,” which explains how states achieve effective governance through deep engagement with society. This theoretical framework posits that governance efficacy stems not from the distant, coercive exercise of power, but rather requires governments to simultaneously maintain “autonomy” (freedom from capture by particularistic interests) and “embeddedness” (close ties with society to obtain information and implementation capacity). In the context of industrial chain governance, this theory provides a structural perspective for understanding how chain leaders achieve development objectives by embedding themselves within socio-economic networks.

Recent literature has expanded upon the embedded autonomy theory by examining its application in specific contexts. Block and Negoita [

20] sought to provide further details regarding the processes through which state officials engage with technocrats and corporations. By developing an economic model incorporating the concept of embedded autonomy, Lyu and Singh [

21] emphasized that close relationships between bureaucrats and industrialists can facilitate the selection of high-growth investments, while also highlighting the importance to guard against corruption resulting from cronyism. Chan and Kwok [

22] contend that under state-led embeddedness, platforms are primarily perceived not as private economic entities but as instruments for delivering public goods and addressing societal challenges. However, most existing studies employ theoretical models or case analysis methods, with few focusing on empirical research regarding specific industrial policies and their implementation effects. This gap in the literature presents an opportunity for this study.

The Chain Leader Policy can be conceptualized as an operationalization of embedded autonomy theory at the meso-level of industrial chains. While Evans’s seminal framework was originally applied to analyze state-society relations at the national level in explaining broad patterns of industrial transformation, the Chain Leader mechanism scales down and adapts this theoretical construct to function within specific sectoral contexts. The “Chain Leader” (a designated government official) embodies the “autonomy” dimension of the state—maintaining bureaucratic capacity and coherence independent from particularistic interests—while their deep engagement in coordinating relationships among firms, universities, and research institutes within the industrial chain exemplifies the “embeddedness” dimension. This institutional design distinguishes the policy from purely hierarchical, top-down industrial interventions and from laissez-faire market governance approaches, thereby providing a concrete empirical context for examining how embedded autonomy operates in contemporary environmental governance—a domain that extends beyond the scope of classical developmental state literature.

Having established embedded autonomy theory as the foundation for understanding the Chain Leader Policy’s coordination mechanisms, we now examine how this theoretical framework intersects with broader institutional environments that shape corporate behavior and policy effectiveness.

2.2. Determinants and Spillover Effects of Greenwashing

Having established embedded autonomy theory as our analytical foundation, we now examine the empirical literature on greenwashing determinants and governance mechanisms. This theoretical lens enables us to systematically analyze how government-market hybrid arrangements can address the coordination failures and information asymmetries that drive greenwashing behavior. The following review follows a logical progression: first examining individual-level and institutional factors that drive greenwashing behavior (

Section 2.2), then analyzing existing governance approaches and their limitations (

Section 2.3), thereby identifying the research gap that our embedded autonomy-based analysis addresses.

Numerous scholars have investigated both internal and external factors influencing corporate greenwashing. External factors encompass inadequate government oversight [

13] and market pressures from consumers [

14], while internal factors involve managerial subjective perceptions regarding greenwashing, such as environmental attitudes [

15] or limited transparency [

23]. However, these studies predominantly adopt singular-factor approaches. Currently, only a limited number of studies examine the impact of institutional pressures on corporate greenwashing from an institutional theory perspective, with findings remaining inconclusive. Chakraborty et al. [

16] demonstrate that coercive isomorphic pressures’ effect on greenwashing remains unaffected by consumer skepticism, whereas economic and normative pressures exhibit varying impacts depending on skepticism contexts. Can and Turker [

17] reveal that public and social welfare logics drive greenwashing, whereas business logic shows no direct effect. Furthermore, corporate greenwashing strategies not only spread contagiously within ESG mutual funds [

3] but also negatively affect purchase intentions for green products from other brands within the same industry [

24]. These findings indicate that while institutional pressures’ influence on corporate greenwashing has gained scholarly attention in recent research, significant gaps remain for further exploration. Moreover, the spillover effects of greenwashing underscore the necessity to investigate industrial chain governance mechanisms for curbing such practices.

2.3. Environmental Governance Mechanisms in Industrial Chains

Building on the understanding of greenwashing determinants and their complex institutional contexts, this section examines how various governance mechanisms have been employed to address these challenges at the industrial chain level. The analysis reveals both the contributions and limitations of existing approaches, providing the foundation for understanding why hybrid governance mechanisms like the Chain Leader Policy merit systematic investigation.

2.3.1. Chain Leader Policy and Environmental Governance: Current Research Status

Recent empirical studies on the Chain Leader Policy have evolved from general economic impact assessments to more specific environmental governance investigations. Early research primarily documented the policy’s effects on enterprise innovation performance, industrial chain resilience, and regional economic development outcomes [

8,

9,

10]. However, emerging evidence suggests significant environmental governance potential that warrants systematic investigation.

Current environmental impact studies reveal three key findings. First, policy implementation correlates with measurable improvements in enterprise environmental performance indicators, including reduced pollution intensity and enhanced green technology adoption rates. Second, industrial chains under Chain Leader coordination exhibit stronger green technology diffusion patterns compared to non-policy chains, with knowledge spillover effects extending across upstream-downstream networks. Third, preliminary evidence suggests that Chain Leader intervention may influence corporate environmental disclosure behavior, though the specific mechanisms through which this occurs remain underspecified.

Despite these promising findings, existing research exhibits critical limitations that constrain systematic understanding of the policy’s anti-greenwashing mechanisms. Methodologically, most studies rely on aggregate environmental outcome measures without examining specific behavioral changes such as greenwashing practices. Theoretically, current analyses lack frameworks explaining how Chain Leader coordination mechanisms systematically address environmental opportunism. Empirically, existing studies overlook institutional contingencies that may moderate policy effectiveness across different contexts. These limitations underscore the need for comprehensive analysis that can illuminate both the operational mechanisms and boundary conditions of Chain Leader environmental governance.

2.3.2. Greenwashing Governance Mechanisms: Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Evidence

Existing literature identifies two predominant modes of environmental governance in industrial chains: government-led governance and market-based governance. As a powerful stakeholder within institutional systems, governments facilitate structural transitions toward sustainability and mitigate greenwashing through proactive policymaking [

25], with specific instruments including government accounting oversight [

26], subsidies [

27], and green financial system regulation [

28]. Market-based governance manifests in two dimensions. First, from a market-position perspective, leading firms employ coordination mechanisms (e.g., reducing supply chain collaboration costs, restructuring trade credit networks) and guidance strategies (e.g., promoting green technology sharing, fostering ecological responsibility awareness) to curb greenwashing [

12,

29], with such governance exhibiting value-creating multiplier effects [

30]. Second, from a cross-organizational perspective, downstream clients’ ESG performance transmits upstream through supply chain power relations, constraining suppliers’ greenwashing [

31].

Building on these governance approaches, theoretical perspectives on greenwashing mitigation draw from multiple disciplinary foundations that illuminate four critical mechanisms. Resource constraint theory suggests that supply–demand relationship stability reduces resource uncertainty that often drives opportunistic environmental behavior. When firms can rely on stable supply chains and predictable demand patterns, they face fewer pressures to engage in short-term environmental deception to maintain competitive position. Transaction cost economics highlights how coordination cost reduction addresses information asymmetries and inefficiencies that create space for environmental opportunism. Lower coordination costs enable better monitoring and verification of environmental claims across supply chain networks.

Resource-based view emphasizes how green collaborative innovation mechanisms transform environmental requirements from external burdens into internal capabilities, reducing incentives for deceptive practices by making genuine environmental performance economically advantageous. Stakeholder theory demonstrates how external scrutiny enhancement creates reputational risks that increase the costs of greenwashing relative to substantive environmental investments. Each mechanism addresses different aspects of the greenwashing problem: resource constraints, information asymmetries, capability deficits, and accountability gaps, respectively.

However, empirical evidence supporting these theoretical mechanisms remains fragmented across different literature streams, with no systematic investigation examining how these mechanisms operate collectively within integrated governance systems like the Chain Leader Policy. This theoretical foundation suggests four specific pathways through which embedded autonomy mechanisms could systematically reduce corporate greenwashing: stabilizing supply–demand relationships to reduce resource constraints, minimizing coordination costs to eliminate information asymmetries, facilitating collaborative innovation to build genuine capabilities, and enhancing external scrutiny to strengthen accountability mechanisms. These theoretical predictions form the basis for our subsequent hypothesis development.

2.3.3. Hybrid Governance Models: Institutional Innovations and Comparative Advantages

International experiences reveal diverse institutional approaches to environmental governance within industrial chains, yet each demonstrates inherent limitations in addressing systemic environmental risks. Market-oriented models such as Germany’s Industrie 4.0 initiative coordinate government-industry-research collaboration primarily for digitalization and manufacturing efficiency rather than systematic environmental governance [

6]. The United States employs voluntary Environmental Protection Agency programs that rely on private sector leadership with limited enforcement mechanisms. Regulatory-driven approaches include France’s extended producer responsibility schemes that mandate lifecycle environmental accountability and the EU’s emerging supply chain due diligence directives. Collaborative governance models are exemplified by Japan’s administrative guidance (gyosei shido), which provides informal coordination between government ministries and industries [

7], and Sweden’s government-facilitated industrial symbiosis networks that foster circular economy principles. However, these international models typically lack a dedicated governmental authority with explicit mandate and comprehensive administrative capacity to coordinate entire industrial chains specifically for mitigating systemic environmental risks such as greenwashing.

China’s Chain Leader Policy represents a distinctive hybrid governance approach that transcends traditional government-market dichotomies through operationalizing embedded autonomy theory. This policy features a unique institutional design wherein local government officials serve as designated “Chain Leaders” who simultaneously maintain bureaucratic independence and deep market engagement [

19]. The policy’s embedded autonomy manifests through four core mechanisms: strategic coordination of industrial chain development planning to resolve upstream-downstream bottlenecks; resource integration among enterprises, academic institutions, and government departments to mitigate information asymmetries [

8]; systemic optimization of industrial chain resource allocation to enhance overall efficiency and resilience [

9]; and targeted intervention providing tailored services to address developmental challenges across chain enterprises [

10]. This institutional architecture enables responsive environmental governance while maintaining necessary autonomy, distinguishing it from both hierarchical state intervention and laissez-faire market mechanisms prevalent internationally.

To contextualize the Chain Leader Policy’s distinctiveness, comparative governance scholarship reveals that different institutional environments have developed varying approaches to industrial coordination challenges [

32,

33].

Table 1 presents a systematic comparison of different governance models across five key dimensions to highlight the Chain Leader Policy’s institutional innovations.

This comparative analysis reveals three critical institutional innovations of the Chain Leader Policy: (1) Formal Cross-Sectoral Authority: Unlike voluntary industry initiatives or informal guidance, Chain Leaders possess explicit administrative mandate spanning entire industrial networks; (2) Systematic Environmental Targeting: While other models treat environmental outcomes as secondary benefits or regulatory compliance issues, this policy explicitly targets environmental opportunism as its primary objective; (3) Hybrid Enforcement Mechanism: The combination of administrative authority with market coordination enables both prevention (through supply chain coordination) and detection (through network monitoring) of greenwashing practices.

The Chain Leader Policy’s hybrid institutional design addresses these limitations by combining formal administrative authority with market coordination mechanisms. Unlike purely voluntary industry initiatives or informal guidance systems, Chain Leaders possess explicit mandate and resource allocation powers to coordinate environmental compliance across entire industrial networks, from upstream suppliers to downstream distributors. This institutional arrangement enables systematic intervention in greenwashing practices while maintaining market efficiency through enterprise-led innovation and competition dynamics.

2.3.4. Research Gaps and Theoretical Opportunities

However, beyond these conventional government-market dichotomies and existing international models, the Chain Leader Policy as a novel embedded autonomy mechanism remains underexplored regarding its systematic impact on corporate greenwashing.

This literature review reveals a fundamental research gap: while environmental governance studies separately examine market coordination [

29,

30] and government regulation [

25,

26], no research systematically investigates how hybrid mechanisms integrate both approaches to address greenwashing’s dual nature—requiring simultaneous coordination and supervision. Existing fragmented approaches cannot explain why traditional single-mechanism governance often fails against sophisticated greenwashing strategies. The Chain Leader Policy represents a unique context to test embedded autonomy theory in environmental governance, yet this opportunity remains unexploited.

This comprehensive review reveals that while existing literature provides valuable insights into greenwashing determinants and various governance approaches, a critical gap remains: systematic empirical analysis of how embedded autonomy mechanisms can coordinate industrial chain-level environmental governance to address greenwashing systematically. Most existing studies examine either government-led or market-based approaches in isolation, without considering hybrid governance forms that integrate state guidance with market coordination through embedded institutional arrangements. Our study addresses this gap by examining China’s Chain Leader Policy as an operationalization of embedded autonomy theory in environmental governance, thereby contributing to both theoretical understanding and practical policy design for sustainable industrial development.

Four interconnected research gaps limit systematic understanding of hybrid governance approaches to environmental opportunism. First, mechanism specification deficit: while existing studies document that various governance approaches can influence environmental behavior, they lack theoretical frameworks explaining how hybrid mechanisms systematically integrate coordination and supervision functions to address greenwashing’s dual nature as both coordination failure and information asymmetry problem. Second, pathway identification absence: current literature treats governance effectiveness as a “black box,” failing to specify the precise channels through which policies like the Chain Leader mechanism operate to reduce environmental opportunism. Third, institutional contingency oversight: although institutional theory suggests that external pressures shape organizational responses to governance interventions, empirical research has not systematically examined how different isomorphic pressures moderate anti-greenwashing policy effectiveness. Fourth, empirical validation gap: despite growing recognition of greenwashing’s systematic nature in industrial chains, large-scale quantitative studies testing hybrid governance approaches remain rare.

These interconnected gaps underscore the need for comprehensive empirical analysis that can illuminate both the operational mechanisms and boundary conditions of embedded autonomy approaches to environmental governance. Our investigation of China’s Chain Leader Policy directly addresses these limitations through systematic examination of mediating pathways (supply–demand stabilization, coordination cost reduction, collaborative innovation enhancement, and external scrutiny amplification) and moderating institutional conditions, thereby contributing to both theoretical advancement and practical policy design for sustainable industrial development. Based on this theoretical analysis and research gap identification, the following section develops specific research hypotheses to guide our empirical investigation.

4. Methodology

Our empirical methodology addresses critical challenges in policy evaluation research through a comprehensive analytical framework grounded in established econometric principles. Policy evaluation in quasi-experimental settings requires careful attention to endogeneity concerns, selection bias, and confounding factors that could compromise statistical inference [

82]. This study employs a multi-period difference-in-differences approach, which is widely recognized as an effective approach for policy evaluation where randomized controlled trials are infeasible [

83]. The method’s effectiveness stems from its ability to simultaneously control for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity through entity fixed effects and common temporal shocks through time fixed effects, thereby isolating the causal impact of the Chain Leader Policy on corporate greenwashing behavior [

84].

Recent methodological advances have addressed concerns about heterogeneous treatment effects in staggered adoption designs, particularly the work by Callaway and Sant’Anna [

85] and Goodman-Bacon [

86], which we incorporate through robust estimation procedures and comprehensive sensitivity analyses. Our variable construction strategy follows established practices in corporate environmental research, with the greenwashing measure building upon the theoretical framework developed by Lyon and Maxwell [

87] and empirically validated by Yu et al. [

88]. The integration of multiple data sources and systematic robustness checks ensures the reliability and validity of our empirical findings, consistent with best practices in corporate governance research [

89].

4.1. Data and Sample

The Chain Leader Policy was first implemented in 2017 in Changsha City, Hunan Province. To ensure symmetry in the pre- and post-policy time windows, this study selects A-share listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2011 to 2023 (six years before and after policy implementation) as the research sample.

To ensure the validity and comparability of our empirical analysis, we implement several sample selection criteria based on established methodological considerations in corporate environmental research. Financial firms are excluded because they operate under fundamentally different regulatory frameworks, accounting standards, and business models compared to non-financial enterprises. Their balance sheet structures, characterized by deposits and loans rather than traditional operating assets and liabilities, make financial ratios and performance metrics non-comparable with industrial firms. Moreover, financial institutions face distinct environmental disclosure requirements and regulatory oversight that differ substantially from the manufacturing and service sectors primarily targeted by the Chain Leader Policy. ST (Special Treatment) companies are excluded due to their financial distress status, which creates systematic differences in strategic behavior, resource allocation decisions, and disclosure incentives. These firms face trading restrictions, heightened delisting risks, and intensive regulatory scrutiny that fundamentally alter their environmental reporting behavior and greenwashing propensity compared to financially healthy enterprises. Including such firms would introduce significant sample heterogeneity and potentially confound the identification of the Chain Leader Policy’s effects on normal operating companies.

Our sample processing follows established methodological protocols in corporate governance research to ensure statistical validity and cross-study comparability. The sample selection criteria are grounded in theoretical and empirical considerations extensively validated in prior research.

We implement four systematic processing steps: (1) Financial firms are excluded following the standard practice established by Fama and French [

90] and widely adopted in corporate governance research. This exclusion is theoretically justified because financial firms operate under distinct regulatory regimes, utilize fundamentally different accounting standards, and face unique capital structure constraints that render traditional financial ratios non-comparable with industrial firms [

91]. (2) Special Treatment (ST) and Particular Transfer (PT) companies are excluded following the methodology established in Chinese corporate governance research [

92]. These firms under regulatory special treatment due to financial distress exhibit systematic differences in strategic behavior and disclosure incentives that could confound our policy evaluation. (3) Firms with missing or abnormal data for key variables are removed following data quality protocols established by Petersen [

93] for panel data analysis. (4) Continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% and 99% percentiles following standard practice [

94] to mitigate the influence of extreme outliers while preserving the underlying data distribution.

The final dataset consists of 12,334 firm-year observations in an unbalanced panel. This processing approach excludes approximately 3.2% of initial observations due to data quality and comparability concerns, consistent with loss rates reported in similar studies using corporate databases [

95].

The raw data on corporate greenwashing are obtained from ESG ratings provided by Bloomberg and HuaZheng. Data on the Chain Leader Policy are manually collected from policy implementation documents published on government websites and economic development zone portals. Data on firms’ green joint patent applications and media coverage come from the CNRDS database, while investor attention data are sourced from Baidu Search Index. Provincial-level environmental NGO counts are manually compiled from the “Environmental Protection” category in the NGO directory on China Development Brief. Other firm-level variables are primarily drawn from the CSMAR database, and city-level data mainly come from relevant years of the China City Statistical Yearbook and government work reports.

Data quality and reliability are ensured through systematic validation procedures following established protocols in large-scale corporate database research [

96]. We implement comprehensive quality controls including: (1) logical consistency verification to ensure financial ratios fall within economically meaningful ranges and percentage variables remain within appropriate bounds; (2) cross-database validation for key firm identifiers and fundamental variables against alternative data sources where available; (3) temporal consistency analysis to identify sudden jumps or structural breaks that could indicate data entry errors, following diagnostic frameworks developed for corporate databases [

97]; and (4) multivariate outlier detection using Mahalanobis distance criteria adapted for panel data applications [

98]. This comprehensive data quality assurance process results in high reliability of our empirical findings and minimizes potential for spurious results arising from data quality issues.

The Chain Leader Policy’s institutional uniqueness lies in its tri-level governance architecture that systematically addresses the coordination failures enabling greenwashing practices. At Level 1, Administrative Coordination Authority operates through Chain Leaders—appointed government officials (typically at vice-mayor or department director level) who possess cross-sectoral coordination authority, resource allocation discretion, and network convening power to coordinate environmental compliance across industry boundaries. At Level 2, Market Coordination Mechanisms leverage Leading Firms (dominant enterprises within each industrial chain) as market-based enforcement agents through green technology spillover requirements, supply chain environmental standards, and competitive benchmarking systems. At Level 3, Social Network Mobilization enables Chain Leaders to activate broader social oversight through media integration, academic collaboration, and public information systems that enable stakeholder monitoring of industrial chain environmental practices.

This tri-level architecture enables the policy to address greenwashing’s multi-stakeholder complexity through institutional mechanisms that traditional environmental regulation lacks.

4.2. Model Settings

The selection of an appropriate empirical methodology is crucial for establishing causal relationships between policy interventions and corporate behavioral outcomes. The Chain Leader Policy exhibits a staggered rollout pattern across different prefecture-level cities over multiple years, creating a quasi-natural experimental setting where firms are exogenously assigned to treatment based on their geographic location and policy timing rather than their own characteristics.

This study employs a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) approach as the primary identification strategy for several reasons. The DID framework allows us to control simultaneously for time-invariant firm heterogeneity through firm fixed effects and common temporal shocks through year fixed effects, thereby isolating the policy’s causal impact on corporate greenwashing behavior from confounding factors. This exogenous assignment mitigates endogeneity concerns that could confound traditional cross-sectional or time-series analyses.

The selection of multi-period difference-in-differences methodology over alternative causal identification strategies is based on systematic evaluation of methodological appropriateness and practical constraints inherent in our research setting. We considered four primary alternatives: instrumental variables (IV), regression discontinuity design (RDD), matching methods, and synthetic control approaches.

Instrumental variables estimation was deemed inappropriate due to the absence of valid instruments that satisfy both relevance and exclusion restrictions for the Chain Leader Policy implementation. Unlike studies examining market-based regulations where natural instruments may exist, the administrative nature of our policy intervention lacks clear exogenous determinants that would not directly affect corporate greenwashing behavior [

99]. Regression discontinuity design was not feasible because the Chain Leader Policy implementation did not follow clear cutoff rules or threshold-based assignment mechanisms required for valid RDD application [

100].

Matching methods, including propensity score matching, were considered but ultimately rejected due to fundamental limitations in addressing time-varying confounders. While matching can control for observable pre-treatment characteristics [

101], it cannot account for unobserved time-varying factors that may simultaneously influence policy adoption and environmental behavior—a critical limitation in our multi-year panel setting. Synthetic control methods, though powerful for aggregate-level policy evaluation [

102], are less suitable for firm-level analysis with large cross-sectional dimensions and limited pre-treatment periods.

In contrast, the multi-period DID approach optimally exploits the staggered implementation pattern of the Chain Leader Policy across cities and years, providing the exogenous variation necessary for causal identification while controlling for both time-invariant firm heterogeneity and common temporal trends [

103]. The method’s robustness has been demonstrated in numerous policy evaluation studies with similar institutional settings [

104,

105].

This study first employs a multi-period DID model to assess the impact of the Chain Leader Policy on corporate greenwashing, as specified in Equation (1). Subsequently, recognizing the endogeneity and efficiency issues associated with the stepwise approach for testing mediation effects, we adopt the two-step method proposed by Jiang [

106]. Equation (2) examines whether the Chain Leader Policy has the expected effect on mechanism variables, while the impact of mechanism variables on the dependent variable is confirmed through theoretical and empirical evidence. Finally, Equation (3) tests whether the three types of institutional pressures moderate the inhibitory effect of the Chain Leader Policy on greenwashing.

In the model specifications, Gws represents the degree of corporate greenwashing, ChainLeader denotes the dummy variable for the Chain Leader Policy, M stands for the mechanism variables, Pressure indicates the moderating variables, and Controls refers to the control variables. The terms μᵢ and μₜ capture firm fixed effects and year fixed effects, respectively, while εᵢ,ₜ represents the random error term. The coefficients α0, β0, and γ0 correspond to constant terms. Subscripts i and t index firms and years, respectively, with standard errors clustered at the city level.

To ensure robust causal identification, this study implements a systematic validation strategy addressing the core identification challenges in quasi-experimental designs. Following established protocols in policy evaluation research for addressing fundamental assumptions underlying difference-in-differences estimation [

103,

107], our comprehensive robustness framework encompasses four critical validation dimensions:

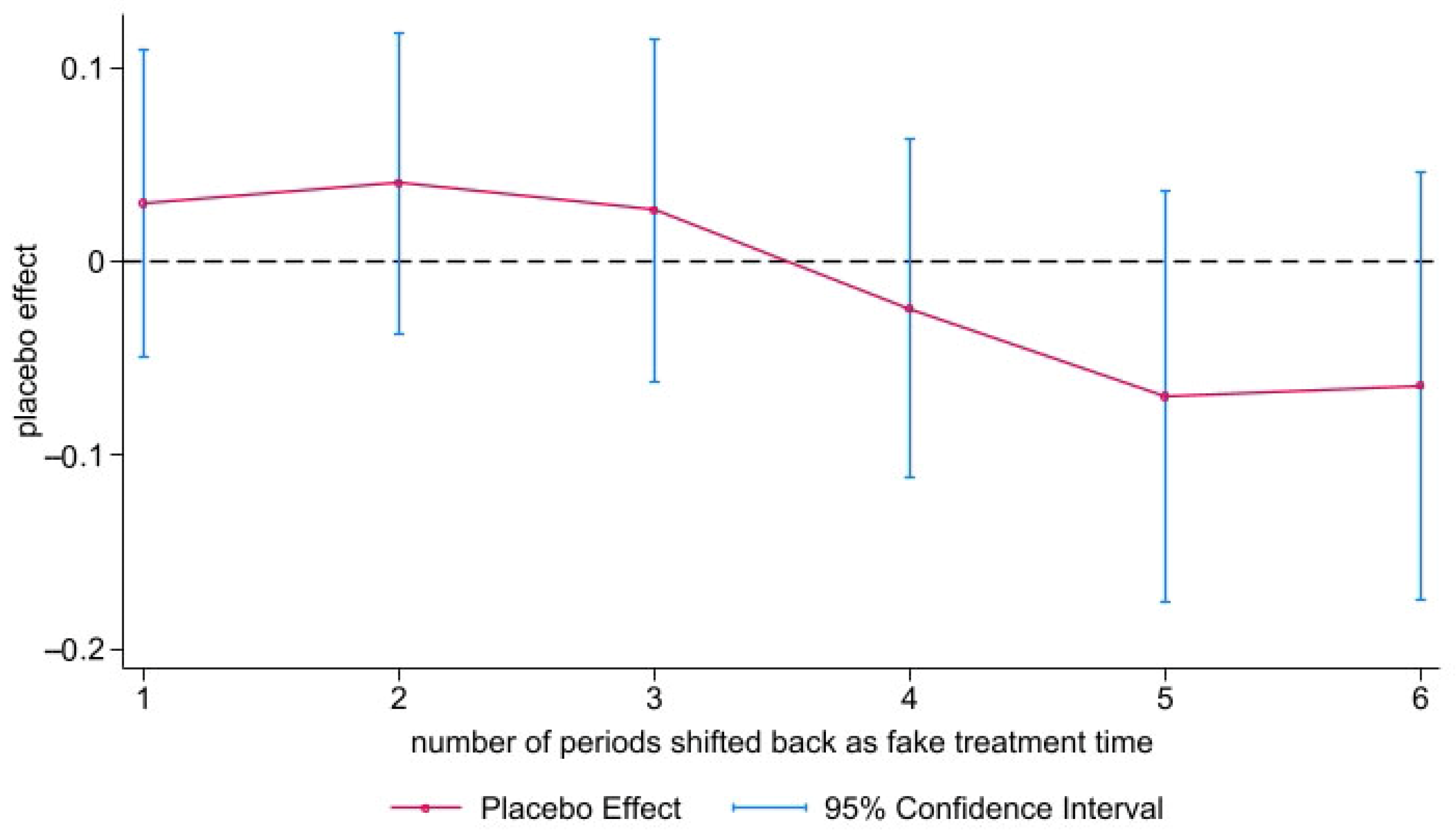

First, parallel trends verification through pre-treatment anticipatory effects testing to validate the fundamental DID assumption that treatment and control groups would follow similar trajectories absent the intervention.

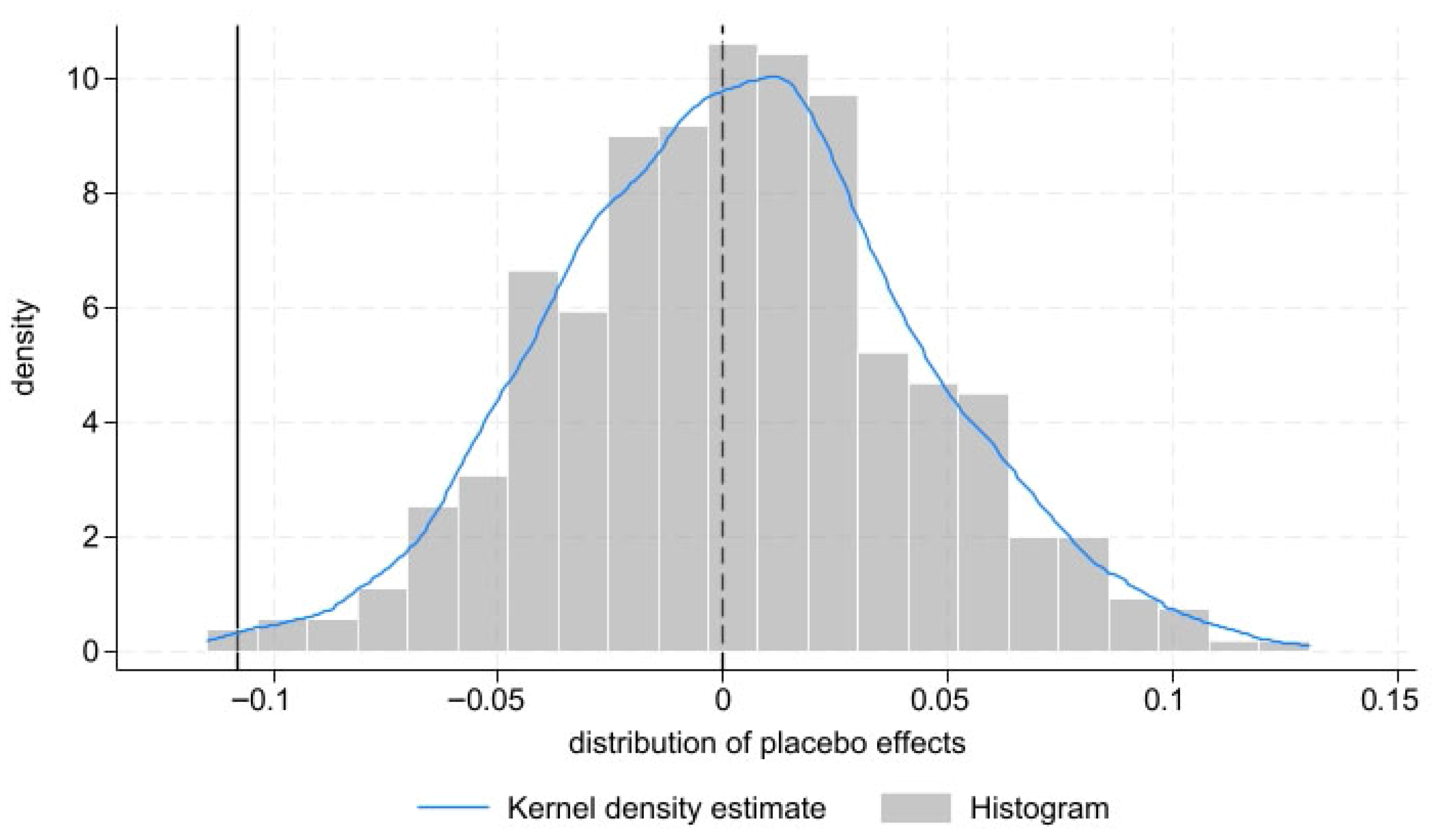

Second, placebo testing using both temporal (testing non-treatment periods) and spatial (testing non-treatment regions) approaches to verify that observed effects are genuinely attributable to the policy intervention rather than spurious correlations or unobserved confounding factors.

Third, selection bias controls through predetermined firm characteristics and propensity score matching techniques to address potential systematic differences between treatment and control groups that could confound our estimates.

Fourth, sensitivity analyses employing alternative model specifications, estimation methods, and sample definitions to assess the stability of our findings across different analytical approaches.

This multi-layered validation strategy addresses the fundamental threats to causal inference in difference-in-differences designs—ensuring treatment exogeneity, ruling out alternative explanations, and validating model assumptions. The detailed implementation of each validation approach is presented in

Section 5.2, providing comprehensive empirical evidence supporting our causal inferences.

4.3. Model Application Conditions and Boundary Analysis

The validity and generalizability of our findings depend on specific theoretical assumptions, methodological requirements, and institutional conditions. This section systematically examines these prerequisites to guide future research applications and policy implementations across different contexts.

4.3.1. Methodological Prerequisites

Our empirical strategy employs three interconnected model specifications—baseline difference-in-differences (Equation (1)), mediation analysis (Equation (2)), and institutional moderation (Equation (3))—each requiring distinct methodological prerequisites.

Our empirical framework requires three methodological foundations for valid causal inference. First, policy exogeneity demands that Chain Leader Policy implementation follows administrative logic rather than firm-specific environmental performance, which our institutional analysis confirms through evidence of administrative hierarchy-driven rollout. Second, temporal stability requires consistent policy mechanisms throughout the analysis period, validated through our robustness checks across multiple implementation phases. Third, treatment independence assumes limited spillover effects between treatment and control groups, though this may be challenged in highly integrated industrial networks where supply chains cross policy boundaries.

The mediation analysis framework operates under distinct validity conditions: mechanism measurability through observable firm behaviors, temporal sequencing following policy implementation, and theoretical independence among proposed pathways. Our four-pathway approach (supply–demand stability, coordination costs, collaborative innovation, external scrutiny) satisfies these requirements through established proxies that demonstrate minimal cross-correlation and clear theoretical distinctions.

4.3.2. Institutional Prerequisites

Cross-context applicability requires three institutional capabilities that determine policy effectiveness:

Administrative Coordination Capacity: Government officials must possess cross-sectoral authority to facilitate multi-stakeholder collaboration. This capacity exists in administrative state traditions (e.g., East Asian developmental states, continental European corporatist systems) but may be limited in market-oriented systems with restricted government roles.

Resource Allocation Authority: Policymakers require meaningful incentives for environmental compliance through regulatory support, financial instruments, or network facilitation. This authority varies significantly across political systems and determines the policy’s enforcement credibility.

Network Convening Legitimacy: Social acceptance of government roles in coordinating business-academia-research partnerships reflects cultural and institutional contexts. High-trust societies with corporatist traditions typically demonstrate greater legitimacy than individualistic, market-oriented environments.

4.3.3. Sectoral and Temporal Conditions

The empirical framework exhibits optimal effectiveness under specific structural conditions:

Industrial Structure Requirements: Manufacturing-intensive economies with clear upstream-downstream relationships facilitate coordination mechanisms central to policy effectiveness. Network-dense industries where firms maintain multiple inter-organizational relationships enable social network mobilization pathways. Our heterogeneity analysis confirms strongest effects in Equipment Manufacturing (−0.160) and Biopharmaceuticals (−0.153), while limited effectiveness appears in rapidly changing sectors like New Energy Vehicles (−0.027).

Temporal Stability Requirements: Model validity requires stable institutional environments, sufficient policy learning periods (typically 2–3 years for coordination mechanisms to mature), and technological stability that maintains supply chain coordination structures. Rapid technological change or major institutional transitions may invalidate core assumptions.

4.3.4. Performance Boundaries and Effect Magnitudes

Our finding of 10.8% greenwashing reduction provides a benchmark for policy effectiveness expectations under optimal conditions. This effect magnitude is conditional on three performance boundaries:

Firm Characteristics: Enhanced effectiveness in state-owned enterprises (coefficient difference: 0.151), firms with stronger green awareness (coefficient difference: 0.172), and highly internationalized companies (coefficient difference: 0.080) suggests that organizational capacity and external pressure amplify policy transmission.

Regional Variations: Effectiveness gradients across Eastern (−0.142), Central (−0.089), and Western (−0.058) regions reflect institutional maturity differences. Eastern regions leverage market coordination mechanisms, while Western regions rely on direct government intervention due to limited coordination infrastructure.

Industrial Chain Specificity: Policy transmission varies systematically across industrial chains, with mature sectors demonstrating stronger effects due to established coordination standards and stable network relationships.

4.3.5. Application Guidelines and Transferability

For practical implementation, policymakers should assess three readiness criteria before adopting similar approaches:

Institutional Readiness Assessment: Evaluate administrative capacity, resource allocation authority, and social legitimacy for government-business coordination

Sectoral Suitability Analysis: Prioritize implementation in sectors with stable supply chains, established technical standards, and mature inter-firm relationships

Regional Adaptation Strategy: Design differentiated approaches reflecting local institutional environments rather than uniform implementation

Transferability Considerations: While context-dependent, the policy’s dual-coordination mechanism (administrative + market) and tri-level governance architecture represent transferable institutional innovations. Countries with strong administrative traditions could emphasize formal coordination components, while market-oriented systems might focus on network mobilization and competitive enforcement mechanisms.

4.4. Variable Measurement

4.4.1. Dependent Variable

Corporate Greenwashing (

Gws) is defined as corporate practices of misleading stakeholders by disclosing extensive ESG data to create a transparent public image while concealing poor actual ESG performance [

88]. Since ESG data are unaudited, the gap between disclosed ESG information and true ESG performance creates opportunities for greenwashing. Following Zhang [

46], this study quantifies corporate greenwashing in ESG disclosures based on ESG rating divergence, calculated as follows:

Here, represents the ESG disclosure score of firm i in year t, while and denote the mean and standard deviation of ESG disclosure scores for firm i’s industry in year t, respectively. These disclosure metrics are measured using Bloomberg ESG scores to assess the volume of disclosed ESG key indicators. Similarly, indicates the ESG performance score of firm i in year t, with and representing the industry mean and standard deviation of ESG performance scores in year t, respectively. The performance metrics are evaluated using HuaZheng ESG scores to capture firms’ actual ESG performance.

4.4.2. Independent Variable

Drawing on the methodology of Zhan and Liang [

10], this study constructs a dummy variable ChainLeader to capture whether a firm was exposed to the Chain Leader Policy shock. It is important to note that this variable specifically measures the policy intervention led by government-appointed Chain Leaders, who are administrative officials, not the presence of Leading Firms, which are dominant enterprises within the industrial chain. The policy effect captured here reflects the government coordination mechanism rather than market-based leadership effects. ChainLeader is defined as ChainLeader = Treat × Post, where the Treat variable equals 1 if: (1) the prefecture-level city where the firm is located implemented the Chain Leader Policy by appointing government officials as Chain Leaders, and (2) the firm operates within the relevant industrial chain designated for this policy intervention; otherwise it is 0. The Post variable equals 1 for years following policy implementation in the firm’s location, and 0 otherwise.

4.4.3. Mediating Variables

(1) Supply–Demand Stability

Following Liu and Zheng [

108], supplier relationship stability (SuppSt) is measured by dividing the number of non-newly-appearing suppliers in a firm’s annual list of top five suppliers by five. Customer relationship stability (CusSt) is calculated analogously. Higher values indicate greater stability in the firm’s supply chain relationships. (The impact of supply chain finance on supplier stability: The mediation role of corporate risk-taking)

(2) Supply–Demand Coordination Costs

Following Cachon et al. [

45], the supply–demand coordination costs (Cost_Coor) is measured by the deviation of a firm’s production volatility from demand volatility. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

In Equation (5), (σ) denotes the standard deviation of the variables, while the numerator and denominator represent the volatility of production and demand, respectively. A larger deviation between production and demand indicates lower precision in supply–demand matching, implying higher supply chain coordination costs for firms. The production quantity of firms is calculated using Equation (6), where Cost represents the firm’s operating costs and Inv denotes the net value of year-end inventory. Firm demand is proxied by operating costs.

(3) Green Collaborative Innovation

Following the approach of Tian and Shi [

109], this study measures firms’ green collaborative innovation level (GreInvja) by summing the number of jointly applied green invention patents and green utility model patents.

(4) External Attention

Following the approach of Li et al. [

110], external attention is captured through investor attention (Index, measured by annual Baidu search frequency for the firm) and media attention (News, measured by annual total news mentions of the firm).

4.4.4. Moderating Variables

Referring to relevant studies [

16,

24], we measure coercive isomorphism using government environmental regulation intensity (Reg, calculated as the ratio of environmental keyword frequency to total words in municipal government work reports [

111], mimetic isomorphism using industry-average greenwashing levels at 2-digit (Imi1) and 3-digit (Imi2) Industry codes, and normative isomorphism using provincial environmental NGO counts by year-end (NGO).

4.4.5. Control Variables

With reference to relevant literature [

88], we control for firm characteristics including size (Size, natural logarithm of total assets plus 1) and age (Age, natural logarithm of listing years plus 1); operational features including leverage ratio (Lev, total debt divided by total assets), return on assets (ROA, net income divided by average total assets), growth opportunities (Growth, revenue growth rate), and cash flow ratio (Cashflow, operating cash flow divided by total assets); governance factors including board size (Board, natural logarithm of directors plus 1), independent director ratio (Indep, independent directors divided by total directors), and top five shareholders’ ownership (Top5); and regional factors including GDP per capita (Gdp), financial development level (Finance, loan balance divided by GDP), and fiscal expenditure ratio (Budget, fiscal expenditure divided by GDP).

6. Contributions and Limitations

Grounded in embedded autonomy theory, this study examines the impact of the Chain Leader Policy on corporate greenwashing behavior using a sample of China’s A-share listed companies (2011–2023). The findings demonstrate that the policy, by complementing both market and administrative mechanisms, effectively reduces corporate greenwashing. This conclusion remains robust after a series of rigorous tests including testing for anticipatory effects, controlling for the interaction term between potential selection criteria and time trends, replacing the dependent variable, placebo tests, assessments of heterogeneous treatment effects, controls for confounding policies, and alternative clustering of standard errors. The results align with prior research and underscore the significance of the Chain Leader Policy in industrial chain governance. More importantly, our findings demonstrate the policy’s concrete contribution to global sustainability agendas. By effectively curbing corporate greenwashing, the Chain Leader Policy facilitates more transparent and substantive environmental practices, which is fundamental to achieving SDG 12. Its role in promoting green collaborative innovation (H2c) directly supports the technological advancement and upgrading of industrial sectors as outlined in SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). Moreover, the policy’s embedded autonomy model, which leverages state-guided partnerships across enterprises, academia, and research institutes, serves as a practical embodiment of the multi-stakeholder partnerships called for by SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

Mechanism analysis results indicate that the Chain Leader Policy—a policy embodying moderate government embedding in markets—inhibits corporate greenwashing through dual pathways; at the supply chain level, it stabilizes corporate supply–demand relationships and reduces coordination costs, and simultaneously, at the social network level, it promotes green collaborative innovation and enhances external scrutiny. The study also incorporates contextual factors to reveal how different institutional pressures moderate the policy’s effectiveness. Specifically, coercive isomorphism strengthens the policy’s impact, mimetic isomorphism weakens it, while normative isomorphism shows no significant moderating effect. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of the Chain Leader Policy on greenwashing is more pronounced in state-owned enterprises, enterprises with stronger green awareness, enterprises with a higher degree of internationalization, and enterprises operating in industries with higher concentration.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several marginal contributions to the literature:

(1) Expanding the research on Chain Leader Policy outcomes from an environmental governance perspective. By enabling authoritative actors to internalize the negative environmental externalities of industrial chains and compensate for the incompleteness of market contracts, this investigation—departing from these institutional characteristics—reveals the system’s effectiveness in curbing greenwashing among chain enterprises through the novel lens of embedded autonomy mechanisms.

(2) This study elucidates the mechanisms through which the Chain Leader Policy inhibits corporate greenwashing. By analyzing four distinct pathways—stabilizing supply–demand relationships, reducing supply–demand coordination costs, promoting green collaborative innovation, and enhancing external scrutiny—operating through both supply chain and social network dimensions, this research provides a micro-theoretical foundation for government-guided green governance.

(3) Addressing gaps in existing literature regarding institutional pressures’ impact on greenwashing. While prior studies have paid limited and inconsistent attention to coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism, we systematically examine their moderating effects within the Chain Leader Policy context. This approach extends the application boundaries of institutional theory while enriching research on corporate greenwashing determinants.

Furthermore, this study demonstrates how hybrid governance mechanisms can advance global sustainability agendas. Our finding of a 10.8% reduction in corporate greenwashing provides empirical support for how national policies can contribute to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) through enhanced corporate environmental integrity. The policy’s role in promoting green collaborative innovation directly supports SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), while its embedded autonomy model exemplifies the multi-stakeholder collaboration advocated by SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

6.2. Policy Heterogeneity Implications

The dual heterogeneity findings across industrial chains and regions reveal critical insights for governance effectiveness and policy design. Our analysis demonstrates that policy effectiveness emerges from systematic alignment between coordination mechanisms, industrial characteristics, and regional institutional environments rather than uniform application.

Three institutional matching principles determine governance outcomes. First, structural stability prerequisite indicates that Chain Leader coordination requires relatively stable supply–demand relationships. The limited effectiveness in New Energy Vehicles and Information Technology reflects coordination failure when confronting rapid structural change. Second, technical standardization foundation demonstrates that effectiveness correlates with industrial maturity, as established standards reduce coordination costs. Third, regulatory complementarity suggests that hybrid governance builds upon existing oversight systems rather than replacing them.

Regional implementation exhibits distinct modalities reflecting adaptive responses to institutional environments. Jiangsu Province employs market-facilitated approaches emphasizing industry alliance coordination and competitive mechanisms. Hunan Province implements guidance-oriented models balancing administrative direction with market incentives. Shaanxi Province adopts support-oriented approaches relying on state-owned enterprises and direct government intervention.

These findings necessitate differentiated policy design rather than uniform implementation approaches. For institutionally mature Eastern regions, emphasis should strengthen market-based coordination functions. For transitional central regions, balanced approaches addressing both coordination failures and capability deficits prove optimal. For developing Western regions, foundational coordination capacity building should precede sophisticated governance mechanisms.

6.3. Practical Implications

This study yields important practical implications for both corporate practice and policy design. Enterprises must embed their operations within the overall ecosystem of the industrial chain, replacing single-link perspectives with collaborative synergy thinking, and leverage the systemic efficacy of the Chain Leader Policy to enhance their green performance. First, establish an internally and externally linked systematic response mechanism to proactively capitalize on the systemic benefits delivered by the Chain Leader Policy. Internally, integrate green development goals into the corporate strategic system, transforming the improved supply–demand stability and reduced supply chain coordination costs resulting from the Chain Leader Policy into advantages in internal resource allocation. For example, synchronize supply chain collaboration data with internal production planning systems, optimize inventory and production rhythms through supply–demand stability, and reduce incentives for greenwashing arising from short-term cost fluctuations. Externally, deeply engage with the industrial chain’s green collaborative innovation system. Rather than treating innovation as an isolated activity, adopt a systems thinking approach to coordinate with upstream and downstream enterprises, participate in co-establishing green technology R&D alliances, share innovation outcomes, and leverage the systemic power of chain-wide collaboration to enhance substantive emission reduction capabilities instead of relying on false claims. Second, incorporate institutional environment responsiveness into the corporate decision-making system. Not only should firms treat it as a mandatory constraint within the industrial chain’s systemic norms—proactively embedding environmental regulations and industry standards set by the Chain Leader into internal compliance systems to strengthen systemic motivation for green transformation through external coercive pressure—but they must also guard against blindly following non-green oriented mimicry behaviors within the industry. Maintain a clear-sighted assessment of their own green capabilities within the industrial chain system, anchor reference standards for substantive emission reduction through participation in chain-wide information sharing systems, and avoid being misled by inefficient imitation logic.

In the green governance of industrial chains, the government must adopt a systematic governance approach and enhance governance efficacy through the logic of holistic coordination. Guided by this principle, the Chain Leader, as a governance hub, needs to systematically leverage its coordination and guidance functions: assist enterprises in establishing relatively stable and healthy supply–demand relationships, gain deep insight into and properly reconcile supply–demand contradictions, and reduce governance challenges at the systemic level by coordinating upstream and downstream relationships. Simultaneously, it should move beyond a siloed support mindset and treat building collaborative platforms for green innovation—encompassing industry, academia, and research—as a systematic project to integrate innovation resources, enabling all parties to form synergies within a collaborative innovation system. Furthermore, it should incorporate supervisory forces such as the media into the pluralistic co-governance system of the industrial chain, establishing coordinated mechanisms among supervisory resources to form systemic supervisory synergy, thereby strengthening the overall effectiveness of green governance in the industrial chain. Additionally, different institutional pressures should be rationally utilized to create systemic linkage effects. From the perspective of whole-industrial-chain system standardization, promote the establishment of industry norms and standards covering the entire industrial chain, systematically embed clear green development responsibilities for enterprises into all nodes of the industrial chain, and ensure the implementation of governance requirements across all segments through institutional constraints. Addressing the contagion of mimetic behaviors, incorporate easily imitated entities such as leading enterprises into the core nodes of the industrial chain guidance system, using them as leverage points to strengthen positive guidance, while linking improved reward-punishment mechanisms to systemic aspects such as industrial chain access and resource allocation, to holistically prevent cross-enterprise collaborative violations such as mimetic greenwashing and collusive greenwashing.

From a global sustainability perspective, the Chain Leader Policy’s demonstrated effectiveness offers insights for international development. Its success in reducing corporate greenwashing while maintaining economic coordination provides a replicable framework for developing economies facing dual challenges of industrial development and environmental protection. This model demonstrates how systematic governance can transform corporate greenwashing into genuine environmental integrity, offering a practical pathway for aligning economic growth with sustainability commitments.

6.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The study identifies several limitations that warrant further research, particularly regarding the generalizability and boundary conditions of our findings across different institutional contexts. The Chain Leader Policy’s replicability depends on three institutional prerequisites: (1) Administrative Coordination Capacity: The ability of government officials to coordinate across sectoral boundaries. (2) Resource Allocation Authority: Government capacity to provide meaningful incentives for environmental compliance. (3) Network Convening Legitimacy: Social acceptance of government roles in facilitating multi-stakeholder coordination. The policy’s dual-coordination mechanism (administrative + market) and tri-level governance architecture represent transferable institutional innovations. Countries with strong administrative traditions (e.g., France, South Korea, Singapore) could potentially adapt the formal coordination authority components, while market-oriented systems (e.g., United States, United Kingdom) might emphasize the network mobilization and market-based enforcement mechanisms.

From a methodological perspective, our ESG rating divergence approach and four-mechanism analysis framework provide replicable tools for evaluating environmental governance interventions across different institutional settings. The difference-in-differences methodology can assess policy impacts in any context with sufficient variation in implementation timing and scope.

Additionally, although our research operationalizes corporate greenwashing through ESG disclosure inaccuracies, firms in complex supply networks increasingly adopt sophisticated strategies including covert carbon accounting manipulation and transferring polluting operations to less-scrutinized subsidiaries. Future studies should develop more comprehensive measurement frameworks capturing these evolving manifestations to generate more nuanced and robust findings.

In addition, the current analysis does not fully embed firms within their industrial chain ecosystems, potentially limiting complete understanding of behavioral logic and policy transmission pathways. Subsequent research could quantify nodal relationship intensities to examine their moderating effects on policy outcomes, trace inter-firm interaction mechanisms, and analyze how the policy influences these network dynamics to produce chain-wide impacts—thereby generating more actionable optimization recommendations. These proposed directions would significantly advance both theoretical and practical understanding of hybrid governance systems’ implementation and effectiveness.