2.1. Business Model Innovation

The concept of BMI is multifaceted and has been interpreted through diverse theoretical perspectives. On one hand, some definitions adopt a broad systems-based view, conceptualizing BMI as an activity system that serves as the level of analysis and emphasizes the mechanisms through which value is created [

16]. On the other hand, BMI has also been examined at a more granular level, focusing on specific components of the business model, such as the “who,” “what,” “when,” “why,” “where,” “how,” and “how much”, to explain how firms innovate across various dimensions of their operations [

17]. In both approaches, BMI is not seen as a mere technological upgrade [

18], but rather as a strategic and essential process [

19], involving the reconfiguration of a firm’s value creation mechanisms or even a complete reinvention of its business model [

4].

Broadly defined, BMI refers to the design, transformation, or reinvention of a firm’s business model to create, deliver, and capture value in novel ways [

20]. This transformation often includes modifications to value propositions, customer segments, revenue models, and supply chain structures, typically in response to technological developments and dynamic market conditions. Digital technologies and platforms play a central role in enabling the development of new, scalable, and customer-centric business models that enhance competitiveness [

21]. BMI increasingly relies on innovations such as digital platforms, the Internet of Things (IoT), AI, and big data analytics to deliver agile, personalized, and efficient solutions [

22,

23].

Simultaneously, a notable shift in consumer behavior toward environmentally and socially responsible consumption has prompted firms to integrate sustainability and ethical considerations into their business models. Aligning business strategies with these values has become essential not only for long-term competitiveness but also for fulfilling corporate social responsibility (CSR) goals. Companies are encouraged to leverage internal assets, such as leadership, corporate culture, and dynamic capabilities, to institutionalize these sustainability values within their organizational DNA [

24]. Sustainability-oriented business models not only contribute to reducing environmental and social harm, but also create long-term advantages, both financial and non-financial, by strengthening legitimacy, reputation, and consumer engagement [

25,

26].

SRC, guided by prosocial values and ethical norms, has become an increasingly influential factor in shaping consumer expectations of corporate behavior [

27]. While SRC is partly influenced by socio-economic factors and personal identity, it also encompasses consumer demands for eco-friendly products, transparent supply chains, fair trade, and socially conscious innovations [

28,

29,

30]. Consumers who identify with SRC view their purchasing decisions as opportunities to drive positive environmental and social change. Accordingly, they are more inclined to support firms that actively demonstrate commitment to these ideals, suggesting that consumer perceptions of innovation are driven by both technological advancement and moral alignment [

12].

Thus, the relationship between BMI and SRC can be framed through the lens of customer value co-creation. Increasingly, firms are redesigning their business models to reflect sustainability-driven motivations, such as lowering carbon emissions, adopting circular economy principles, ensuring supply chain transparency, and embedding ethical innovation practices into core operations [

29,

31,

32]. When aligned with these values, BMI strengthens competitive positioning, enhances brand perception, and builds trust with socially conscious customers [

26,

33].

Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

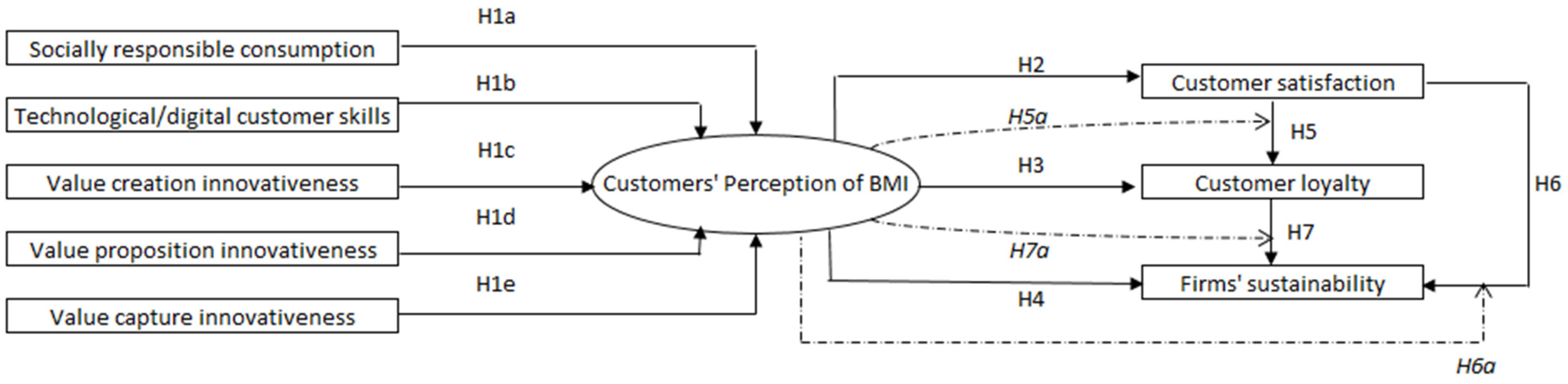

H1a. Socially responsible consumption influences customers’ perception of business model innovation.

The rise of digital platforms and e-commerce has significantly increased consumer access to information about corporate practices, enabling more informed and socially responsible purchasing decisions [

34]. This digital empowerment has occurred in parallel with the evolution of TCS, defined as individuals’ ability to interact with, utilize, and derive value from digital technologies, services, and platforms. As firms increasingly deliver personalized and data-driven experiences, TCS has emerged as a critical determinant of consumer behavior with shaping expectations, engagement patterns, and loyalty [

35]. A central element of TCS is digital literacy, which determines how effectively consumers interact with digital interfaces and how readily they adopt innovative products and services. This creates a feedback loop: firms rely on digitally competent users to test, refine, and co-create effective BMI strategies [

36]. Therefore, BMI is driven not only by technological capabilities but also by the digital sophistication of end-users.

Empirical studies support a positive relationship between TCS and BMI. Digitally literate consumers increasingly expect seamless, personalized, and omnichannel experiences, prompting firms to embed capabilities such as automation, AI-powered services, and predictive analytics into their business models [

37,

38]. In response, firms have redesigned customer interaction channels, integrating tools such as chatbots, virtual assistants, and AI-driven service interfaces, which have become core components of digital BMI strategies [

39]. TCS also plays a central role in how firms capture value. Many businesses are shifting toward platform-based and subscription-driven models, which depend on sustained customer interaction with digital ecosystems. These models enable continuous data collection and monetization, allowing companies to offer insight-driven, value-added services. However, the effectiveness of these models depends on customers’ ability to understand, navigate, and trust digital environments, reinforcing the positive influence of TCS on BMI [

40].

In sum, the relationship between TCS and BMI is mutually reinforcing. As digital environments evolve, customer digital proficiency becomes an increasingly powerful force shaping business innovation strategies. Firms that align their models with the digital capabilities of their customers are better positioned to succeed in a rapidly transforming market. Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1b. Technological/digital customer skills influences customers’ perception of business model innovation.

VCrI refers to a firm’s capability to deliver novel and impactful solutions that meet evolving customer needs and foster long-term relationships [

41]. It involves the continuous improvement of products, services, and internal processes, anchoring the firm’s capacity to differentiate itself in competitive markets through innovation-driven strategies [

42].

Existing literature confirms a strong positive relationship between BMI and VCrI. Customers who perceive a firm’s offerings as innovative and relevant are more likely to demonstrate higher levels of satisfaction, loyalty, and engagement, thereby reinforcing the firm’s strategic positioning [

38]. Often, perceived innovativeness is associated with technological sophistication and functional enhancement, positioning the firm as a leader within its industry. This, in turn, encourages customer advocacy and deeper engagement [

40]. Furthermore, customer participation in the co-creation of innovation through feedback, collaborative development, or direct interaction, which ensures that innovations reflect not only technological advancements but also customer expectations and values [

43]. Trust, transparency, and a customer-centric approach to innovation enhance the credibility and perceived authenticity of BMI. As firms adopt these strategies, customer perceptions of innovativeness improve, bolstering brand affinity, customer confidence, and long-term competitiveness. Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1c. Value creation innovativeness influences customers’ perception of business model innovation.

VPI reflects a firm’s ability to creatively differentiate itself in the market by addressing new or previously unmet customer needs. This may include the development of novel products and services, increased personalization, or the delivery of enhanced and seamless customer experiences [

44,

45]. VPI often necessitates fundamental changes in how value is created, delivered, and captured, making it a core driver of BMI strategies [

46].

Empirical evidence shows that customers react positively to innovative value propositions, especially when such innovations address quality improvements, emerging needs, and the use of advanced technologies [

47,

48]. The effectiveness of BMI is shaped in large part by customer expectations and perceptions. Firms that align their value propositions with dynamic consumer demands are more likely to achieve higher CS and brand loyalty. Moreover, this alignment improves both financial and non-financial outcomes, strengthening the firm’s market relevance and competitive positioning [

49]. Based on this foundation, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1d. Value proposition innovativeness influences customers’ perception of business model innovation.

VCI refers to a firm’s strategic capability to extract value, such as profits, revenue, and competitive advantage, by adapting its revenue generation mechanisms to changing market conditions and technological developments [

14]. This often includes innovating pricing strategies, forming strategic alliances, and managing intellectual property to ensure sustainable growth and long-term market relevance [

4].

Given that BMI inherently involves redesigning value creation and delivery processes, including revenue models, customer engagement strategies, and distribution channels, the relationship between VCI and BMI is reciprocal and mutually reinforcing. On one hand, innovative value capture mechanisms provide the necessary resources and strategic incentives for firms to pursue and implement BMI. On the other hand, as business models evolve in response to external pressures, they often require a recalibration of value capture strategies to remain competitive and relevant to customer expectations and technological trends [

13]. Recent studies also highlight the growing role of sustainability in shaping VCI. Firms committed to sustainable business practices are increasingly adopting alternative revenue models, such as carbon credits, pay-per-use schemes, and circular economy approaches, to align value extraction with ethical, environmental, and social objectives [

15]. These transformations show that VCI not only supports the renewal of business models but also enhances alignment with the values of socially conscious consumers, ultimately strengthening brand image and market positioning. Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1e. Value capture innovativeness influences customers’ perception of business model innovation.

The individual hypotheses (H1a–H1e) illustrate how each specific dimension whether ethical, technological, or strategic independently contributes to customers’ perception of BMI. Each factor captures a distinct aspect of consumer value orientation or firm-level innovation capacity, influencing how customers evaluate the novelty, relevance, and strategic value of a firm’s business model. In practice, however, these factors rarely function in isolation. Customer perceptions of BMI are shaped by a multidimensional interplay of socially grounded values (e.g., SRC), digital competencies (e.g., TCS), and innovation strategies (e.g., VCrI, VPI, and VCI). This integrated view reflects the reality that consumers form holistic judgments of firms based on the simultaneous expression of ethical alignment, technological sophistication, and the perceived innovativeness of value delivery. Therefore, synthesizing the theoretical and empirical evidence from all BMI components, we propose the following comprehensive hypothesis:

H1. Socially responsible consumption (SRC), Technological/digital customer skills (TCS), Value creation innovativeness (VCrI), Value proposition innovativeness (VPI), and Value capture innovativeness (VCI) collectively influence customers’ perception of business model innovation (BMI).

2.4. Firm Sustainability

FS extends beyond corporate growth and profitability to encompass broader societal goals, including environmental protection, social equity, and economic resilience [

66]. This multidimensional concept integrates economic, environmental, and social pillars, all of which are essential for achieving genuine long-term sustainability. However, the degree to which firms can effectively implement sustainability strategies varies depending on factors such as organizational size, maturity, and strategic capacity [

67]. While sustainability reporting, such as adherence to GRI standards, is commonly used to signal commitment [

67,

68], genuine sustainability requires deeper structural transformation in business operations and logic. In general, financially stronger firms are better positioned to adopt sustainability practices, as they can allocate greater resources to such initiatives [

69].

A growing body of research highlights a strong positive association between sustainability performance and financial outcomes [

70]. The real impact, however, emerges when firms embed sustainability principles directly into their core strategies through BMI. Sustainable BMI enables firms to deliver socially and environmentally responsible products, expand into new markets, and develop novel revenue streams, thereby reinforcing long-term viability and competitive advantage [

71,

72]. Moreover, customer perception plays a crucial role in driving FS. As consumer awareness of ethical and environmental issues increases, firms that innovate responsibly are more likely to gain trust, enhance brand reputation, and strengthen CL. A business model perceived as both innovative and sustainability-oriented not only garners public support but also contributes to financial resilience and long-term business success. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4. Customers’ perception of business model innovation positively influences firm sustainability.

CS is widely recognized as a foundational element in the development of CL. While these two concepts are closely linked, they differ in nature: satisfaction typically represents a post-usage evaluation, which is more immediate and situational, whereas loyalty reflects an enduring commitment and a deeper emotional attachment to the brand [

73]. Loyalty develops progressively across multiple stages, such as cognitive, affective, conative, and behavioral, indicating that it is not merely a transactional outcome but rather a multi-layered process shaped by product perceptions, individual preferences, and social dynamics [

73,

74]. Extensive empirical research confirms that CS plays a critical role in shaping CL. Satisfied customers are more likely to repurchase from firms that consistently meet or exceed their expectations [

75], and CS is considered essential in building both attitudinal and behavioral loyalty [

76,

77]. Interestingly, the relationship between CS and CL may exhibit a nonlinear pattern, where incremental increases in satisfaction can result in disproportionately stronger loyalty [

78]. Based on this evidence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5. Customer satisfaction positively influences customer loyalty.

While CS is a key determinant of CL, the strength of this relationship can be influenced by contextual factors. One important factor is customers’ perception BMI. When customers perceive that a firm is innovating not only in its products and services but also in how it creates, delivers, and captures value, satisfaction is more likely to translate into long-term loyalty, reinforcing the firm’s strategic relevance and competitive advantage [

38]. Understanding customer priorities enables firms to tailor offerings to align with expectations, while trust and perceived quality further strengthen this bond [

79,

80].

In this sense, BMI may act as a moderating mechanism that enhances the CS–CL relationship. Firms that demonstrate visible, customer-centric innovation, such as transparent operational processes, personalized service models, and adaptive engagement strategies, are more likely to convert satisfied customers into loyal advocates [

64,

65]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5a. Customers’ perception of business model innovation moderates the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty.

CS is instrumental in achieving FS. As noted by [

81], CS directly contributes to customer retention, revenue growth, and long-term profitability, which are key pillars of sustainable performance. As sustainability becomes a global priority, consumers increasingly favor companies that demonstrate social and environmental responsibility. In response, firms are embedding sustainability into their business strategies, frequently adopting models such as the circular economy, which require significant operational adaptations and enhanced capabilities [

82,

83]. Sustainable practices align with customer values and drive satisfaction. For instance, green initiatives have been shown to significantly enhance CS, which, in turn, increases repurchase intentions and long-term engagement [

84]. Satisfied customers reinforce FS by promoting consistent interactions, brand loyalty, and reputational resilience [

85]. Based on this evidence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6. Customer satisfaction positively influences firm sustainability.

While CS contributes significantly to FS, the strength of this relationship may be amplified by customers’ perception of BMI. When firms adopt innovative business models that integrate sustainability principles, such as transparency, circularity, and social equity, and customers are more likely to interpret their satisfaction as part of a broader ethical alignment [

12]. This perception increases consumer trust, advocacy, and willingness to support the firm over time, thereby strengthening the CS–FS connection. Thus, BMI acts as a moderating factor that deepens the impact of satisfaction on FS by enhancing alignment with customer expectations and shared values [

27,

85]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6a. Customers’ perception of business model innovation moderates the relationship between customer satisfaction and firm sustainability.

CL plays a vital role in enhancing FS, particularly by reinforcing the economic dimension of long-term viability [

86]. Loyal customers contribute to consistent revenue through repeat purchases, premium pricing, and reduced acquisition costs. They also act as brand advocates, strengthening market positioning and defending against competitive pressures [

86,

87]. This sustained profitability motivates firms across industries to adopt sustainability-oriented strategies as a form of differentiation [

29,

32], However, the magnitude of loyalty’s impact on FS may vary depending on whether a firm operates in product- or service-based industries [

81]. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7. Customer loyalty positively influences firm sustainability.

Beyond financial contributions, CL influences FS strategies both strategically and reputationally. Loyal customers often expect firms to align with ethical and environmental standards, creating pressure and opportunities for companies to adopt sustainability initiatives [

88,

89]. This expectation encourages firms to embed sustainability within their core business models to maintain and strengthen loyalty relationships [

90]. Moreover, socially responsible innovation enhances brand reputation and increases customers’ willingness to support and advocate for the firm [

91]. In this regard, customers’ perception of BMI acts as a critical moderating factor. When customers view a firm’s business model as innovative, particularly in its sustainability orientation, they are more likely to associate their loyalty with shared values [

15,

51]. This perception amplifies the impact of CL on FS, reinforcing both economic and reputational sustainability outcomes. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7a. Customers’ perception of business model innovation moderates the relationship between customer loyalty and firm sustainability.