Advancing Hospital Sustainability: A Multidimensional Index Integrating ESG and Digital Transformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Hospital Sustainability Evaluation

2.2. The Nexus of ESG and DX Practices and Hospital Performance

3. Materials and Methods

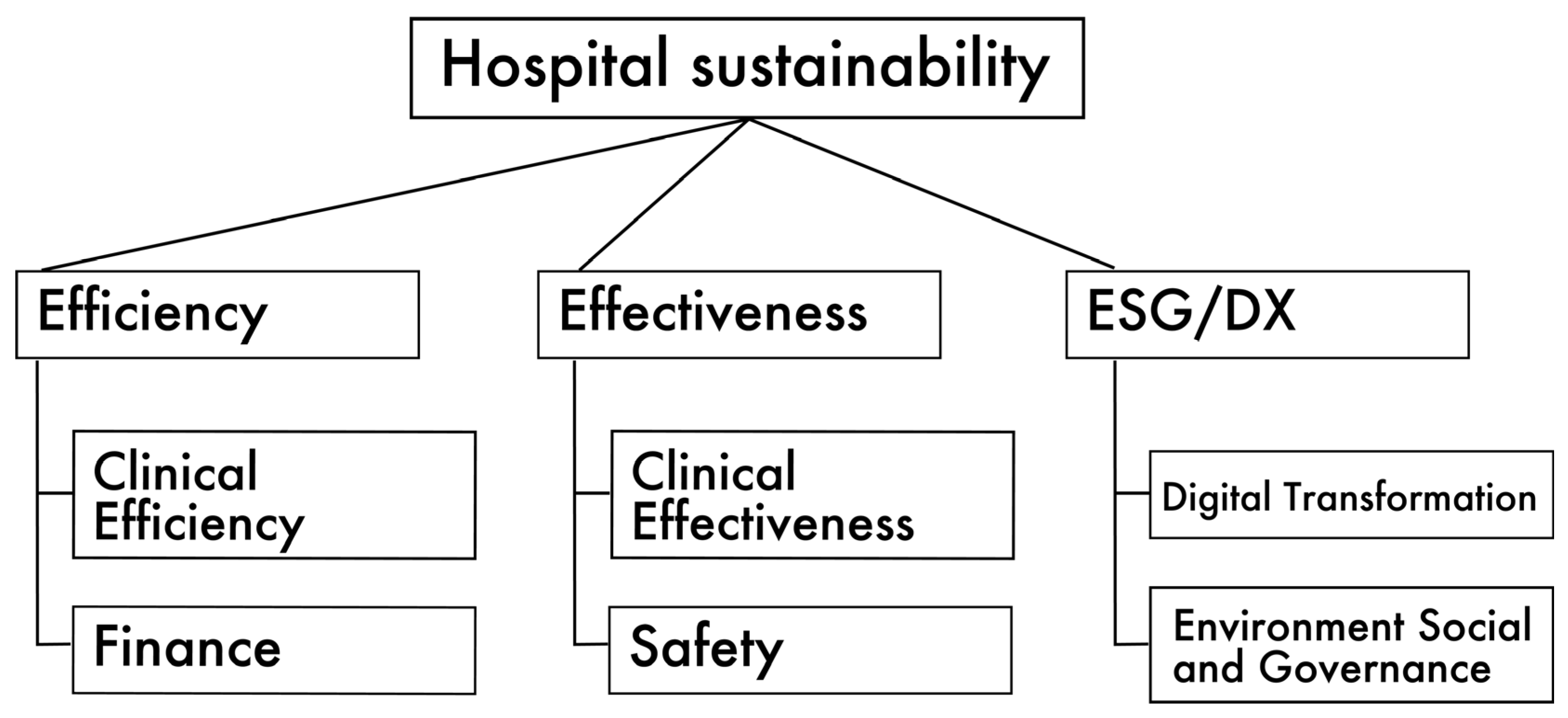

3.1. Concept of the Hospital Sustainability Evaluation System

3.2. DEA Model

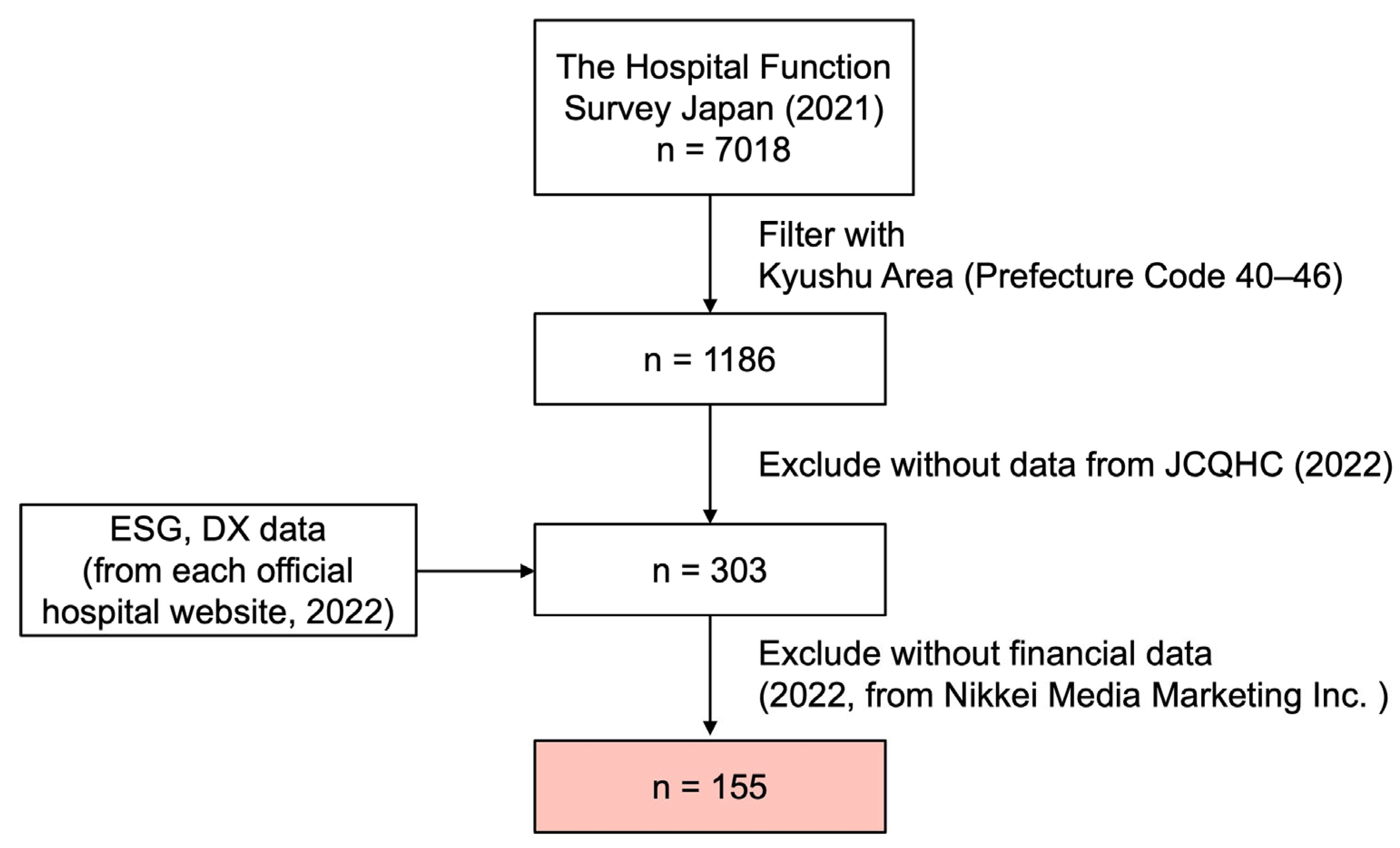

3.3. Data and Sample

4. Results

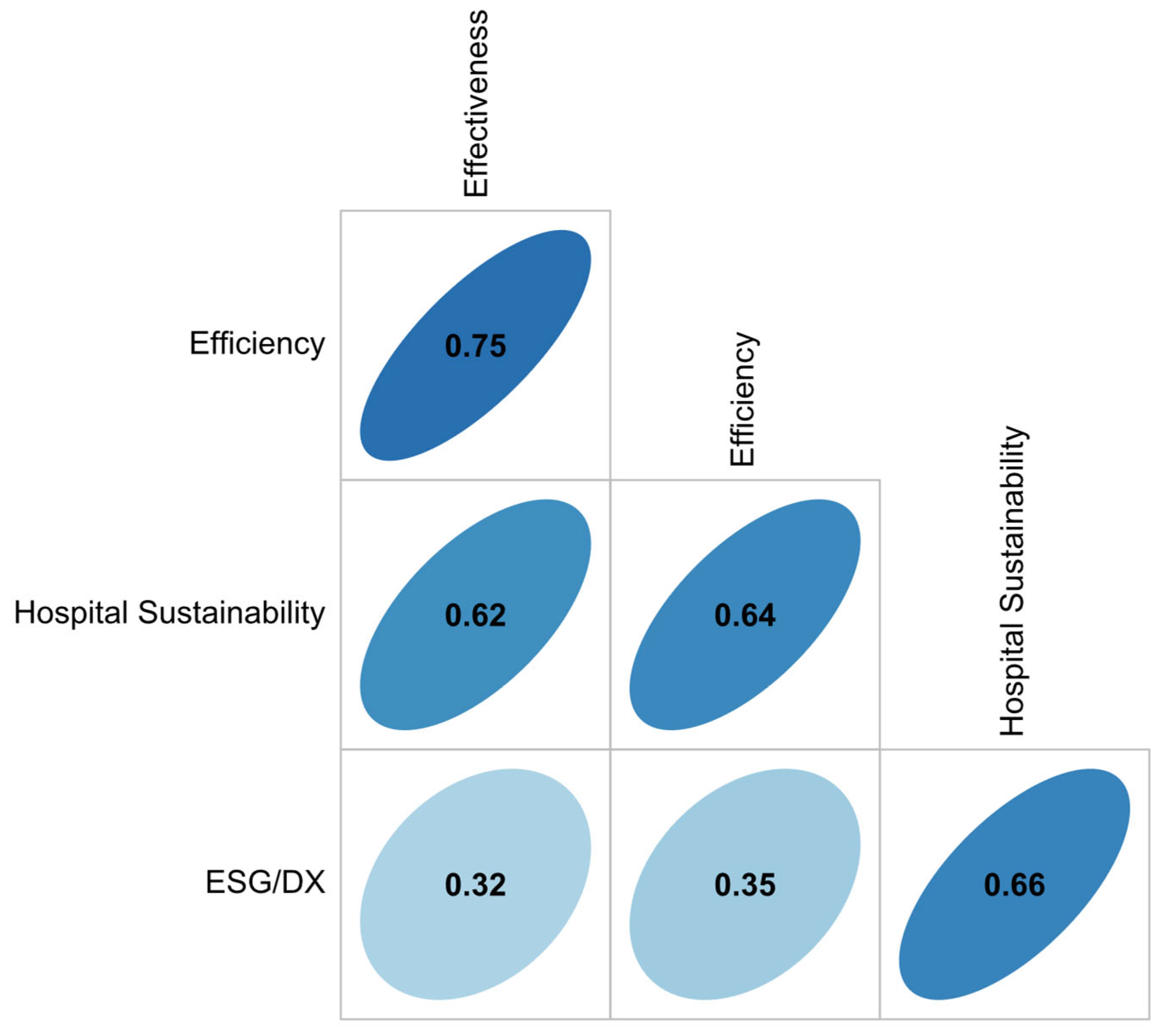

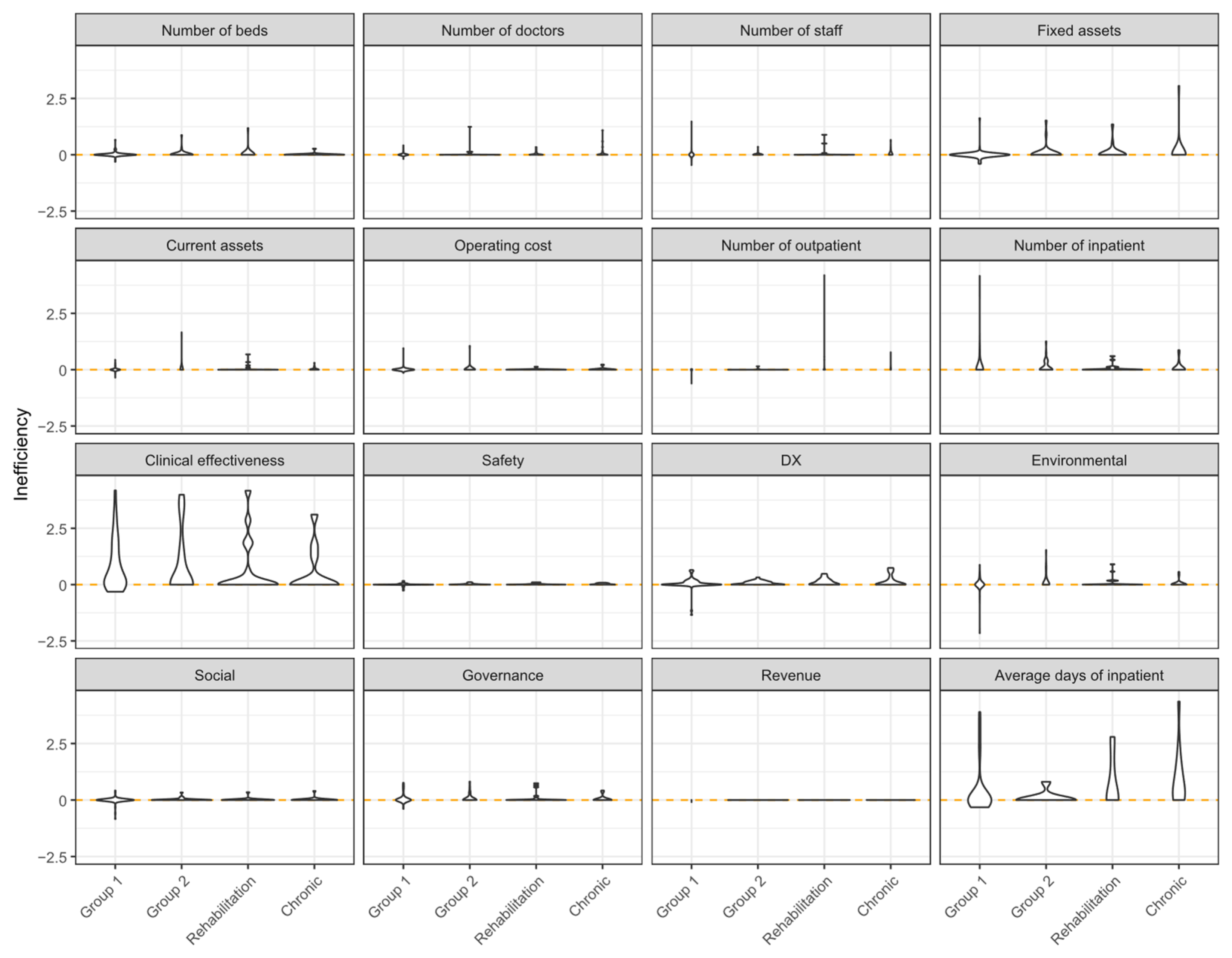

4.1. Estimated Hospital Performance

4.2. Financial Implications of ESG Transparency in Hospitals

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Practical and Policy Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, P. ESG and Responsible Institutional Investing Around the World: A Critical Review; CFA Institute Research Foundation: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.-T.; Wang, K.; Sueyoshi, T.; Wang, D.D. ESG: Research progress and future prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGain, F.; Naylor, C. Environmental sustainability in hospitals—A systematic review and research agenda. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2014, 19, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepetis, A. Sustainable finance in sustainable health care system. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 8, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakielski, M.L. Moving Forward with ESG, Sustainability, and Corporate Responsibility. Front. Health Serv. Manag. 2023, 40, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of the Japanese Health Care System. 2023. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryouhoken/iryouhoken01/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Ferreira, D.; Marques, R. Do quality and access to hospital services impact on their technical efficiency? Omega 2019, 86, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.; Pang, R.-Z.; Liu, S.-T.; Bai, X.-J. Most productive types of hospitals: An empirical analysis. Omega 2021, 99, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimprich, A.; Young, S.B. Environmental footprinting of hospitals: Organizational life cycle assessment of a Canadian hospital. J. Ind. Ecol. 2023, 27, 1335–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.H.; Noor, F.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Asghar, S.; Yusuf, A.A.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Hussain, A.; Badran, M.F.; Shahapurkar, K. Environmental performance of alternative hospital waste management strategies using life cycle assessment (LCA) approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Adardour, Z.; Derj, A.; Bami, A.; Hussainey, K. A PRISMA-Based Systematic Review on Economic, Social, and Governance Practices: Insights and Research Agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1896–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, M.; Bhan, I.; Seth, S. Digitalisation and firm-level ESG performance and disclosures: A scientometric review and research agenda. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, A.R.; Chapman, A.J.; Yoshida, K.; Xie, J.; Imbulana, J.; Takeda, S.; Manag, S. ESG metrics and social equity: Investigating commensurability. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 920955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Tanaka, Y.; Keeley, A.R.; Fujii, H.; Managi, S. Do investors incorporate financial materiality? Remapping the environmental information in corporate sustainability reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2924–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J. Corporate Environmental Sustainability and DEA. In Handbook of Operations Analytics Using Data Envelopment Analysis; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 483–498. [Google Scholar]

- İlgün, G.; Konca, M. Assessment of efficiency levels of training and research hospitals in Turkey and the factors affecting their efficiencies. Health Policy Technol. 2019, 8, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Gong, J. Impacts of comprehensive reform on the efficiency of Guangdong’s county public hospitals in 2014–2019, China. Health Policy Technol. 2022, 11, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top, M.; Konca, M.; Sapaz, B. Technical efficiency of healthcare systems in African countries: An application based on data envelopment analysis. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetim, B.; Sönmez, S.; Konca, M.; İlgün, G. Benchmarking countries’ technical efficiency using AHP-based weighted slack-based measurement (W-SBM): A cross-national perspective. Health Policy Technol. 2023, 12, 100782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J. Data envelopment analysis application in sustainability: The origins, development and future directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, G.D.; Trivitt, J.S. Incorporating quality into the measurement of hospital efficiency: A double DEA approach. J. Product. Anal. 2013, 40, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lys, T.; Naughton, J.P.; Wang, C. Signaling through corporate accountability reporting. J. Account. Econ. 2015, 60, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 434–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, F. CSR initiatives as market signals: A review and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Nozawa, W.; Yagi, M.; Fujii, H.; Managi, S. Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billi, A.; Bernardo, A. The effects of digital transformation, IT innovation, and sustainability strategies on firms’ performances: An empirical study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimene, S.; Coluccia, D.; Fontana, S.; Bernardo, A. Formal Institutions and Voluntary CSR/ESG Disclosure: The Role of Institutional Diversity and Firm Size. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 5147–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimene, S.; Coluccia, D.; Fontana, S.; Gulluscio, C.; Bernardo, A.; Carnegie, G.D. Discerning the state of the art in Italy of voluntary disclosure on biodiversity and endemic species. Meditari Account. Res. 2024, 32, 2348–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, Y.A. Health Care Benchmarking and Performance Evaluation; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-C.; Yu, M.-M.; Chang, C.-C.; Hsu, S.-H.; Managi, S. The enhanced Russell-based directional distance measure with undesirable outputs: Numerical example considering CO2 emissions. Omega 2015, 53, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toloo, M.; Tone, K.; Izadikhah, M. Selecting slacks-based data envelopment analysis models. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 308, 1302–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.P.; Managi, S.; Matousek, R. The technical efficiency of the Japanese banks: Non-radial directional performance measurement with undesirable output. Omega 2012, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chou, S.-Y.; Zhu, J. Incorporating health outcomes in Pennsylvania hospital efficiency: An additive super-efficiency DEA approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2014, 221, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. Variations on the theme of slacks-based measure of efficiency in DEA. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 200, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.W.; Seiford, L.M.; Tone, K. Data Envelopment Analysis: A Comprehensive Text with Models, Applications, References and DEA-Solver Software; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Halkos, G.; Petrou, K.N. Treating undesirable outputs in DEA: A critical review. Econ. Anal. Policy 2019, 62, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of super-efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 143, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. On the Consistency of Slacks-based Measure-max Model and Super-slacks-based Measure Model. Univers. J. Manag. 2017, 5, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, E.; Gabutti, I.; Frisicale, E.M.; Di Pilla, A.; Pezzullo, A.M.; de Waure, C.; Cicchetti, A.; Boccia, S.; Specchia, M.L. Assessing hospital performance indicators. What dimensions? Evidence from an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsantonis, S.; Pinney, C.; Serafeim, G. ESG integration in investment management: Myths and realities. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanchel, I.; Lassoued, N. ESG disclosure and the cost of capital: Is there a ratcheting effect over time? Sustainability 2022, 14, 9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Milne, B.; Parker, K.; Hider, P.; Lay-Yee, R.; Cumming, J.; Graham, P. Efficiency, effectiveness, equity (E3). Evaluating hospital performance in three dimensions. Health Policy 2013, 112, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gok, M.S.; Sezen, B. Analyzing the ambiguous relationship between efficiency, quality and patient satisfaction in healthcare services: The case of public hospitals in Turkey. Health Policy 2013, 111, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Sub-Indicators | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Variable Type | Efficiency | Effectiveness | ESG/DX | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of beds | 170.71 | 128.32 | 27.00 | 1137.00 | Input | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Number of doctors | 22.38 | 28.05 | 3.73 | 270.80 | Input | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Number of employees | 254.07 | 208.58 | 26.00 | 1658.00 | Input | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Number of outpatients | 172.96 | 140.05 | 1.97 | 842.86 | Output | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Number of inpatients | 151.98 | 107.39 | 8.65 | 718.05 | Output | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Average days of inpatient | 54.68 | 64.95 | 4.50 | 556.93 | Undesirable output | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Clinical effectiveness | 8.56 | 0.52 | 6.84 | 9.61 | Output | Yes | Yes | |||

| Quality improvement | 2.76 | 0.29 | 2.00 | 3.40 | ||||||

| Medical treatment | 2.91 | 0.13 | 2.42 | 3.09 | ||||||

| Clinical function | 2.90 | 0.18 | 2.18 | 3.33 | ||||||

| Safety | 5.49 | 0.41 | 4.46 | 6.33 | Output | Yes | Yes | |||

| Patient safety | 2.83 | 0.15 | 2.31 | 3.23 | ||||||

| Infection control | 2.66 | 0.31 | 2.00 | 3.33 | ||||||

| Digital transformation | 1.74 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 7.00 | Output | Yes | Yes | |||

| Environmental | Environmental disclosure | 2.12 | 1.22 | 1.00 | 8.00 | Output | Yes | Yes | ||

| Social | 9.91 | 2.81 | 4.43 | 17.00 | Output | Yes | Yes | |||

| Social disclosure | 4.08 | 2.67 | 0.00 | 11.00 | ||||||

| Local collaboration | 2.91 | 0.34 | 2.00 | 4.00 | ||||||

| Accessibility | 2.92 | 0.18 | 2.43 | 3.43 | ||||||

| Governance | 5.69 | 1.30 | 2.48 | 8.23 | Output | Yes | Yes | |||

| Governance disclosure | 2.90 | 1.26 | 0.00 | 5.00 | ||||||

| Governance assessment | 2.79 | 0.18 | 2.23 | 3.23 | ||||||

| Fixed assets (million JPY) | 4734.44 | 6324.33 | 64.96 | 34,453.41 | Input | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Current assets (million JPY) | 2729.27 | 3968.14 | 226.68 | 24,461.30 | Input | Yes | Yes | |||

| Operation cost (million JPY) | 5363.98 | 6967.41 | 411.42 | 35,298.21 | Input | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Revenue (million JPY) | 5566.28 | 7406.41 | 335.50 | 37,262.28 | Output | Yes |

| # of Hospitals | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | |||||

| Efficiency score | 155 | 0.93 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 2.38 |

| Effectiveness score | 155 | 0.97 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 1.54 |

| ESG/DX score | 155 | 0.89 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 2.05 |

| Sustainability score | 155 | 1.09 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 2.04 |

| ROA (%) | 155 | 1.38 | 5.18 | −20.58 | 29.54 |

| Leverage (%) | 154 | 192.25 | 203.11 | 3.57 | 586.14 |

| Group 1 hospital | |||||

| Efficiency score | 84 | 0.84 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 2.38 |

| Effectiveness score | 84 | 0.91 | 0.2 | 0.07 | 1.37 |

| ESG/DX score | 84 | 0.77 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 1.93 |

| Sustainability score | 84 | 1.05 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 2.04 |

| Group 2 hospital | |||||

| Efficiency score | 30 | 1.08 | 0.24 | 0.74 | 1.84 |

| Effectiveness score | 30 | 1.03 | 0.16 | 0.74 | 1.52 |

| ESG/DX score | 30 | 1.07 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 2.05 |

| Sustainability score | 30 | 1.13 | 0.16 | 1.01 | 1.82 |

| Rehabilitation hospital | |||||

| Efficiency score | 20 | 0.98 | 0.3 | 0.28 | 1.4 |

| Effectiveness score | 20 | 1.01 | 0.21 | 0.58 | 1.54 |

| ESG/DX score | 20 | 1.05 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 1.71 |

| Sustainability score | 20 | 1.14 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 1.39 |

| Chronic hospital | |||||

| Efficiency score | 21 | 1.05 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 1.77 |

| Effectiveness score | 21 | 1.06 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 1.54 |

| ESG/DX score | 21 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.3 | 1.79 |

| Sustainability score | 21 | 1.17 | 0.19 | 1.02 | 1.7 |

| Dependent Variable: Efficiency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | Group 1 Hospital | Group 2 Hospital | Rehabilitation Hospital | Chronic-Care Hospital | |

| ESG/DX | 0.092 * | 0.129 * | −0.009 | 0.196 | −0.245 |

| (0.054) | (0.077) | (0.121) | (0.182) | (0.168) | |

| Effectiveness | 1.184 *** | 1.185 *** | 1.354 *** | 1.086 *** | 1.155 *** |

| (0.094) | (0.133) | (0.253) | (0.270) | (0.363) | |

| Hospital group fixed | Yes | ||||

| Location fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 155 | 84 | 30 | 20 | 21 |

| R2 | 0.609 | 0.575 | 0.713 | 0.672 | 0.74 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.579 | 0.529 | 0.603 | 0.481 | 0.599 |

| Dependent Variable: ROA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | Group 1 Hospital | Group 2 Hospital | Rehabilitation Hospital | Chronic-Care Hospital | |

| ESG/DX | −2.208 * | −4.189 ** | −0.793 | −3.802 * | −1.358 |

| (1.218) | (1.863) | (3.463) | (1.982) | (2.660) | |

| Effectiveness | −0.882 | −2.131 | 2.378 | −7.479 ** | −0.277 |

| (2.137) | (3.237) | (7.199) | (2.952) | (5.209) | |

| Leverage | −0.005 ** | −0.004 | −0.008 * | −0.007 * | −0.005 |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.005) | |

| Hospital group fixed | Yes | ||||

| Location fixed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 84 | 30 | 19 | 21 |

| R2 | 0.182 | 0.213 | 0.318 | 0.694 | 0.516 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.112 | 0.117 | 0.011 | 0.449 | 0.193 |

| Outcome Variable | Key Explanatory Factors | Main Results | Hospital Group Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlations among scores | Efficiency, Effectiveness, Sustainability | Strong positive correlations | Consistent across groups |

| ESG/DX | Weaker but still positive correlations with other scores | Higher variance: ESG/DX awareness still limited in most hospitals | |

| Efficiency | Effectiveness | Positive and significant for all hospital groups | Consistent across groups |

| ESG/DX | Positive relationship with efficiency | Significant in small–middle-scale hospitals (Group 1); not significant in other hospitals | |

| ROA (Profitability) | Effectiveness | Negative association with ROA | Significant in rehabilitation hospitals; not significant in other hospitals |

| ESG/DX | Negative association with ROA | Stronger in small–middle-scale (Group 1) and rehabilitation hospitals; not significant in other hospitals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takeda, M.; Xie, J.; Kurita, K.; Managi, S. Advancing Hospital Sustainability: A Multidimensional Index Integrating ESG and Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198787

Takeda M, Xie J, Kurita K, Managi S. Advancing Hospital Sustainability: A Multidimensional Index Integrating ESG and Digital Transformation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198787

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakeda, Midori, Jun Xie, Kenichi Kurita, and Shunsuke Managi. 2025. "Advancing Hospital Sustainability: A Multidimensional Index Integrating ESG and Digital Transformation" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198787

APA StyleTakeda, M., Xie, J., Kurita, K., & Managi, S. (2025). Advancing Hospital Sustainability: A Multidimensional Index Integrating ESG and Digital Transformation. Sustainability, 17(19), 8787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198787