Research on the Effect of Economics and Management Major Teachers’ Teaching on Students’ Course Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Customer Satisfaction

2.2. Research on Student Satisfaction

2.3. Perceived Value Theory

2.4. SOR Theory

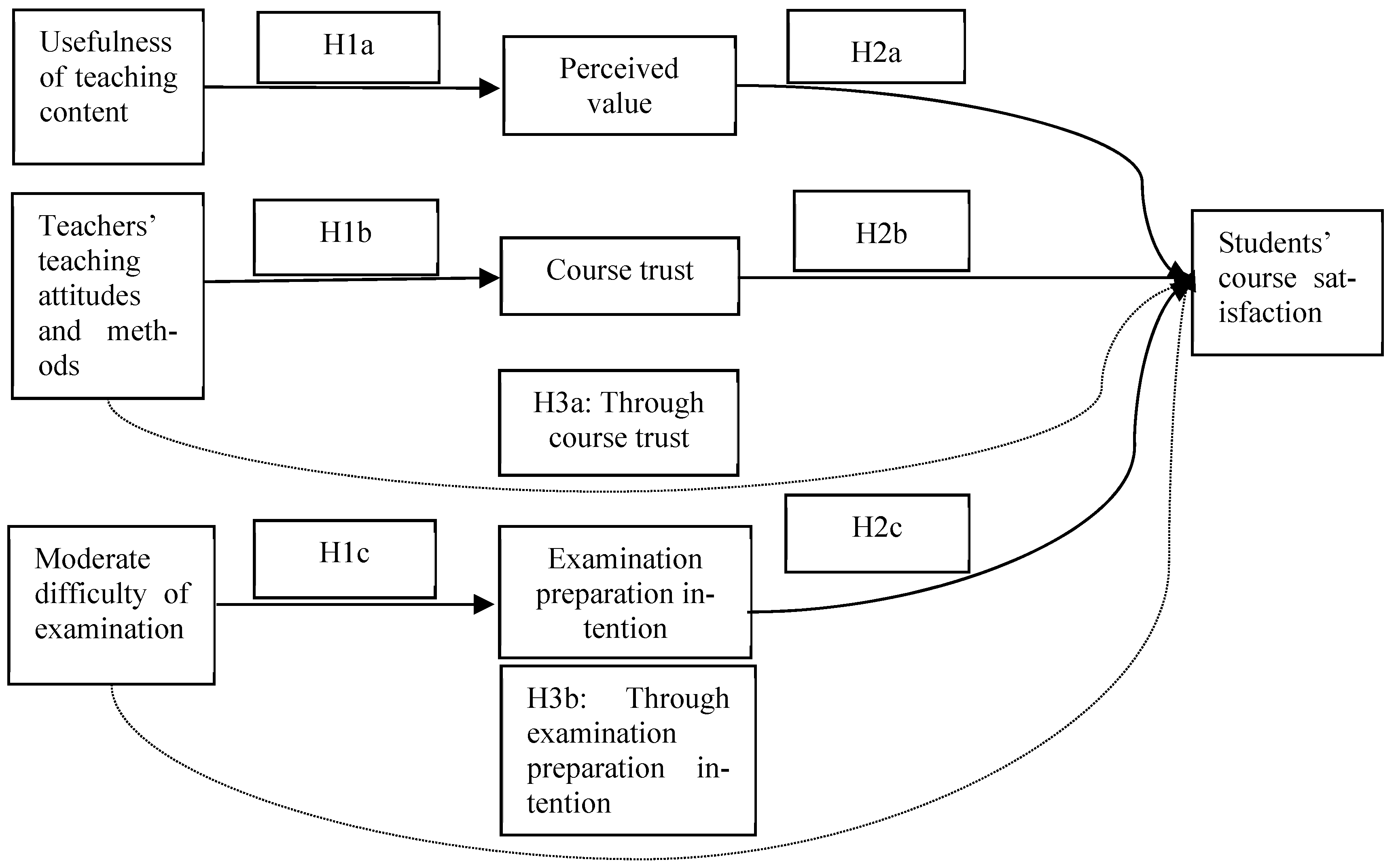

3. Research Hypotheses and Model Construction

3.1. Research Hypotheses

3.1.1. Influence of Teachers’ Teaching on Students’ Psychology

3.1.2. Influence of Students’ Psychology on Their Course Satisfaction

3.1.3. Mediating Effect of Course Trust and Examination Preparation Intention

3.2. Model Construction

4. Method

4.1. Questionnaire Design

4.2. Data Collection

5. Result

5.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

5.1.1. Reliability Test

5.1.2. Validity Test

5.2. Normality Test

5.3. Correlation Analysis

5.4. Regression Analysis

5.4.1. Impact of Teachers’ Teaching on Students’ Psychology

5.4.2. Impact of Students’ Psychology on Students’ Course Satisfaction

5.5. Mediating Effect Test

5.6. Summary of Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion on Key Findings

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Teachers’ teaching has a differentiated driving effect on students’ psychology: the usefulness of teaching content is the key path to enhancing students’ perceived value; teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods are the core means to building trust in a course; and the moderate difficulty of examination drives students’ examination preparation intention.

- (2)

- Students’ psychology is the core means for the transformation of course satisfaction: perceived value directly drives course satisfaction; course trust is the cornerstone of course satisfaction and plays a significant mediating role between teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods and students’ course satisfaction, and students’ examination preparation intention positively promotes course satisfaction and plays a significant mediating role between moderate difficulty of examination and course satisfaction.

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tran, Q.H.; Nguyen, T.M. Determinants in student satisfaction with online learning: A survey study of second-year students at private universities in HCMC. Int. J. TESOL. Educ. 2022, 2, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarenko, Y.; Mavondo, F.T.; Gabbot, M. International and local student satisfaction: Resources and capabilities perspective. J. Market. High Educ. 2004, 14, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, L.A. Comparative study between UK and US: The student satisfaction in higher education and its influential factors. J. Market. Manag. 2005, 21, 859–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Kim, P.B.; Poulston, J.; Hosp, J. An examination of university student workers’ motivations: A New Zealand hospitality industry case study. Tour. Educ. 2020, 32, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanova, N. Assessment of satisfaction with the quality of education: Customer satisfaction index. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 182, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleford, K.; Lee, K. Online Postgraduate Education: Re-imagining Openness, Distance and Interaction; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, M.R. Students are not customers: Reframing student’s role in higher education through value Co-creation and service-dominant logic. In Improving the Evaluation of Scholarly Work; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, G.; Wood, G. Are university students really customers? When illusion may lead to delusion for all. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 21, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- De-Juan-Vigaray, M.D.; Ledesma-Chaves, P.; Eloy Gil-Cordero, E.G.-G. Student satisfaction: Examining capacity development and environmental factors in higher education institutions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, V.F.; Galina, S.V.R. Experiential learning in entrepreneurship education: A systematic literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 121, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Becker, J.A.H.; Buckley, M.R. Considering the labor contributions of students: An alternative to the student-as-customer metaphor. J. Educ. Bus. 2003, 78, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, S.; Lalitha, F. Students’ satisfaction in higher education literature review. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 533–539. [Google Scholar]

- Borishade, T.T.; Ogunnaike, O.O.; Salau, O.; Motilewa, B.D.; Dirisu, J.I. Assessing the relationship among service quality, student satisfaction and loyalty: The NIGERIAN higher education experience. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danjuma, I.; Raslia, A. Imperatives of service innovation and service quality for customer satisfaction: Perspective on higher education. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 40, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. The role played by the broadening of marketing movement in the history of marketing thought. J. Publ. Pol. Market. 2005, 24, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Rabinovich, E.; Hou, H. Customers complaints in online shopping: The role of signal credibility. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2015, 16, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Suh, Y.H. Why do users switch to a disruptive technology? An empirical study based on expectation-disconfirmation theory. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilatinova, N. Social commerce: Factors affecting customer repurchase and word of- mouth intentions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Liu, F.; Cho, D.; Jia, Z. Investigating switching intention of e-commerce live streaming users. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Market. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, T.; Liu, C. An empirical study on the effect of e-service quality on online customer satisfaction and loyalty. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2010, 1, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaily, L.; Soelasih, Y. What effects repurchase intention of online shopping. Int. Bus. Res. 2017, 10, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C. The customer satisfaction–loyalty relation in an interactive e-service setting: The mediators. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.; Lee, Y.; Kim, E.; Griffin, M. Modeling consumer satisfaction and word-of-mouth: Restaurant patronage in. Korea J. Serv. Mark. 2005, 19, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Dalla Pozza, I.; Ganesh, J. Revisiting the satisfaction–loyalty relationship: Empirical generalizations and directions for future research. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, G.; Divya, A. A study on satisfaction of students of private and government schools. IJRA—Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2019, 6, 753–756. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, P.C.; Huang, R. A study on the factors influencing student satisfaction in vocational college based on the customer satisfaction theory model. Adv. Vocat. Tech. Educ. 2024, 6, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.M.; Asimiran, S.; Kadir, S.A. Student satisfaction of university service quality in Malaysia: A review. Inter J. Acad. 2022, 11, 677–688. [Google Scholar]

- Pezeshki, R.E.; Sabokro, M.; Jalilian, N. Developing customer satisfaction index in Iranian public higher education. Int. J. Edu. Manag. 2020, 34, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Demtriou, C. Arguments against applying a customer-service paradigm. Acad. Adv. J. 2008, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, Z.; Gao, Q. Satisfaction Index in Higher Education. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2008, 3, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Jingyi, M. The estimation and test for CSI model. Stat. Decis. 2006, 2, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Andrich, D. Advanced Social and Educational Measurement; Murdoch University Press: Perth, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, N.C. Factors affecting student satisfaction with higher education service quality in Vietnam. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.M.; Iglesias, M.P.; Torres, P.R. A new management element for universities: Satisfaction with the offered courses. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2005, 19, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.H.; Galambos, N. What satisfies students? Mining student-opinion data with regression and decision tree analysis. Res. High. Educ. 2004, 45, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-Y.; Wang, J.C.; Li, T.H.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Chung, S.-C. Teacher and student satisfaction with air conditioners in elementary schools: A coastal Taiwan case study. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 123, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcadu, M.; Cataldo, R.; Migliorini, L. Eating away from home: A quantitative analysis of food neophobia (FNS) and satisfaction with food life (SWFLS) scales among university students. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 131, 05573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J.; Port, G. Life satisfaction. Encycl. Adolesc. 2017, 2, 2165–2176. [Google Scholar]

- Steare, T.; Munoz, C.G.; Sullivan, A.; Lewis, G. The association between academic pressure and adolescent mental health problems: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.; Linley, P.A. Life satisfaction in youth. In Increasing Psychological Well-being in Clinical and Educational Settings: Interventions and Cultural Contexts; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Wang, X.; Bian, Y.; Wang, L. The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between stress and life satisfaction among Chinese medical students: Across-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.T.Q.; Nguyen, B.T.N.; Nguyen, N.P.H. Academic stress and depression among Vietnamese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of life satisfaction and resilience. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 27217–27227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, F.; Gao, C.; Zhu, X.; Lian, L. How to enhance student satisfaction in Chinese open education? A serial multiple mediating model based on academic buoyancy and flow experience. Acta Psychol. 2025, 256, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D.W.; Daly, A.L.; Chamberlain, S.; Sadreddini, S. ‘Sink or swim’: Buoyancy and coping in the cognitive test anxiety-academic performance relationship. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 36, 1807–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Rajala, R. Continued use of mobile instant messaging apps: A new perspective on theories of consumption, flow, and planned behavior. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2020, 38, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josefina, P.; Gemma, R.; Serra, L.; Marianna, S.; Angels, X. Influence of learning styles on undergraduate nursing students’ satisfaction with the flipped course methodology. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 153, 106807. [Google Scholar]

- Willingham, D.T.; Hughes, E.M.; Dobolyi, D.G. The scientific status of learning styles theories. Teach. Psychol. 2015, 42, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elntib, S. Instructor Maladaptive and Adaptive Relational Styles (I-MARS) as drivers of online-student retention and satisfaction. Comput. Educ. Open 2025, 8, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; He, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Chen, C.; He, Y. Acceptance or satisfaction of blended learning among undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 147, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.A.; Roach, E.J.; Natarajan, J.; Karkada, S.; Cayaban, A.R.R. Flipped course improves Omani nursing students performance and satisfaction in anatomy and physiology. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missildine, K.; Fountain, R.; Summers, L.; Gosselin, K. Flipping the course to improve student performance and satisfaction. J. Nurs. Educ. 2013, 52, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.M.; Natarajan, J.; Labrague, L.; Omari, O.A. Paradoxical effect of flipped course on nursing students’ learning ability and satisfaction in a fundamental of nursing clinical course: A quasi-experimental study. J. Prof. Nurs. 2025, 57, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routon, P.W.; Walker, J.K. Relative age, college satisfaction, and student perceptions of skills gained. Res. Econ. 2025, 79, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appuhamilage, K.S.M.; Torii, H. The impact of loyalty on the student satisfaction in higher education: A structural equation modelling analysis. High. Educ. Eval. Dev. 2019, 13, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton-Knapp, S.L.; Krentler, K.A. Measuring student expectations and their effects on satisfaction: The importance of managing student expectations. J. Mark. Educ. 2006, 28, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, A.V. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 3, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, N.; Kalini, Z.; Francisco, J.L.-C. Assessing determinants influencing continued use of live streaming services: An extended perceived value theory of streaming addiction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sinha, N.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J. Determining factors in the adoption and recommendation of mobile wallet services in India: Analysis of the effect of innovativeness, stress to use and social influence. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveena, K.; Thomas, S. Continuance behavioural intention Facebook: A study of perceived enjoyment and TAM. Bonfring Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2014, 4, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, D.; Triyason, T. User intention towards a music streaming service: A Thailand case study. KnE Soc. Sci. 2018, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Peterson, R.T. Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: The role of switching costs. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Cumiskey, K.J.; Xiao, Q.; Alford, B.L. The impact of perceived value on behavior intention: An empirical study. J. Glob. Bus. Manag. 2010, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sengoz, A.; Cavusoglu, M.; Kement, U.; Bayar, B.S. Unveiling the symphony of experience: Exploring flow, inspiration, and revisit intentions among music festival attendees within the SOR model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Cai, L.; Ma, F.; Wang, X. Revenge buying after the lockdown: Based on the SOR framework and TPB model. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, R.-S.; Zhang, C.-X. Live streaming E-commerce platform characteristics: Influencing consumer value co-creation and co-destruction behavior. Acta Psychol. 2024, 243, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, T.L.; Schenk, C.T. An empirical investigation of the S-O-R paradigm of consumer involvement. Adv. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 696. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, D.; John, R. Store atmosphere: An environmental psychology approach. J. Retailing. 1982, 58, 34–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Hooi, T.D.; Zaib, A.A.; Rehman, U. Integrating the SOR model to examine purchase intention based on Instagram sponsored advertising. J. Promot. Manag. 2023, 29, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiranto, R.; Slameto, S. Alumni satisfaction in terms of course infrastructure, lecturer professionalism, and curriculum. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, J.; Douglas, A.; Barnes, B. Measuring student satisfaction at a UK university. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2006, 14, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovitch, N.; Yavich, R. Classroom climate and student self-efficacy in e-learning. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2022, 80, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.M.; Healy, M.A. Key factors influencing student satisfaction related to recruitment and retention. J. Market. High Educ. 2008, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahara, M.F.; Castro, A.L. Teaching strategies to promote immediacy in online graduate courses. Open Prax. 2015, 7, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, A.; Chang, J.; Dufy, T.; del Valle, R. The effects of teacher social presence on student satisfaction, engagement, and learning. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2004, 31, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, M.T. Students’ expectations and students’ satisfaction: The mediating role of excellent teacher behaviors. Teach. Psychol. 2021, 48, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, A. Caring teachers: The key to student learning. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 2007, 43, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.; Choi, S.; Lim, C.; Leem, J. Effects of different types of interaction on learning achievement, satisfaction and participation in web-based instruction. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2002, 39, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.; Shepherd, D.A.; Prentice, C. Using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis for a finer-grained understanding of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putulowski, J.R.; Crosby, R.G. Effect of personalized instructor-student e-mail and text messages on online students’ perceived course quality, social integration with faculty, and institutional commitment. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2019, 21, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazier, R.A. Connecting in the Online Classroom: Building Rapport Between Teachers and Students; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius-White, J. Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, W.J.; Gillaspy, J.A., Jr.; Hancock, F. Predicting academic success with early, middle, and late semester assessment of student–instructor rapport. Teach. Psychol. 2017, 44, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipayung, F. The impact of service quality factors on college student satisfaction. Int. J. Manag. Stud. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 6, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, A.; Kiran, R. The technology interface and student engagement are significant stimuli in sustainable student satisfaction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-L.; Hwang, G.-J. A self-regulated flipped classroom approach to improving students’ learning performance in a mathematics course. Comput. Educ. 2016, 100, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, C.; Schuessler, J.B. A preliminary framework to guide implementation of the flipped course method in nursing education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 34, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Lee, S.E.; Bae, J.; Kang, S.; Choi, S.; Tate, J.A.; Yang, Y.L. Undergraduate nursing students’ experience of learning respiratory system assessment using flipped course: A mixed methods study. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 98, 104664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Kim, S. An online communication skills training program for nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rincón, Y.R.; Munárriz, A.; Ruiz, A.M. Flipped classroom or flip to foster self-regulation competencies in mathematics in economics and business students. Int. J. Educ. Res 2025, 130, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, G.D.; Carrasco-Poyatos, M.; Burgueño, R.; Granero-Gallegos, A. Teaching style and academic engagement in pre-service teachers during the COVID-19 lockdown: Mediation of motivational climate. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 992665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, N. Who is the main influencer on safety performance of dangerous goods air transportation in China? J. Air Transp. Manag. 2019, 75, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ariffin, S.K.; Richardson, C.; Wang, Y. Influencing factors of customer loyalty in mobile payment: A consumption value perspective and the role of alternative attractiveness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | Measurement Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Teachers’ teaching | Usefulness of teaching content (UTC) | Q5. In class, the teacher will explain theoretical knowledge in connection with practical situations. |

| Q6. In class, the teacher will focus on explaining the corresponding course content based on students’ future needs for job hunting, postgraduate entrance examination, civil service examination and entrepreneurship. | ||

| Q7. In class, the teacher will conduct relevant case analyses and problem discussions based on students’ future needs for job hunting, postgraduate entrance examination, civil service examination and entrepreneurship. | ||

| Teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods (TTAM) | Q8. Teachers prepare lessons carefully. | |

| Q9. Teachers have a proper attitude towards course, arrive at the classroom early and do not change or miss courses without reason. | ||

| Q10. Teachers actively manage the course, care for and attract students. | ||

| Q11. Teachers adopt appropriate teaching methods such as case teaching, problem discussion and artificial intelligence teaching based on the course content explanation, and try to give lectures based on the teaching materials as much as possible. | ||

| Moderate difficulty of examination (MDE) | Q12. Teachers try to impart more and newer knowledge when teaching. | |

| Q13. During the examination, teachers will set questions based on the textbooks. | ||

| Q14. Teachers assess students with an attitude that does not make examination too difficult or too easy for students. | ||

| Student psychology | Perceived value (PV) | Q15. The content of the course is practical and resonates with me. |

| Q16. The content of the course can meet my actual needs (such as job hunting, postgraduate entrance examination, civil service examination, and entrepreneurship.). | ||

| Q17. Learning this course knowledge from the teacher makes me feel a sense of achievement. | ||

| Course trust (CT) | Q18. I believe the teacher wants to do her/his best to teach this course well. | |

| Q19. The teacher treats all students equally in class. | ||

| Q20. I think the content explained by the teacher is reliable and trustworthy. | ||

| Examination preparation intention (EPI) | Q21. I believe that by studying hard for the examination, I will achieve good grades. | |

| Q22. If I don’t study hard for the examination, my grades will be poor or I may even fail. | ||

| Q23. I am willing to prepare for the examination actively. | ||

| Student course satisfaction (SCS) | Q24. I’m satisfied with the course content. | |

| Q25. I’m satisfied with the teaching attitude and methods of the teachers in course. | ||

| Q26. My grade is in line with my efforts. | ||

| Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient | Number of Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Usefulness of teaching content | 0.785 | 3 |

| Teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods | 0.819 | 4 |

| Moderate difficulty of examination | 0.751 | 3 |

| Perceived value | 0.766 | 3 |

| Course trust | 0.784 | 3 |

| Examination preparation intention | 0.744 | 3 |

| Students’ course satisfaction | 0.779 | 3 |

| The overall questionnaire | 0.937 | 22 |

| Variables | Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test | Shapiro–Wilke Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | p | W | p | |

| Usefulness of teaching content | 0.235 | <0.001 | 0.894 | <0.001 |

| Teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods | 0.246 | <0.001 | 0.891 | <0.001 |

| Moderate difficulty of examination | 0.240 | <0.001 | 0.894 | <0.001 |

| Perceived value | 0.215 | <0.001 | 0.913 | <0.001 |

| Course trust | 0.195 | <0.001 | 0.929 | <0.001 |

| Examination preparation intention | 0.207 | <0.001 | 0.913 | <0.001 |

| Students’ course satisfaction | 0.213 | <0.001 | 0.909 | <0.001 |

| UTC | TTAM | MDE | PV | CT | EPI | SCS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UTC | 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| TTAM | 0.415 ** | 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| MDE | 0.469 ** | 0.432 ** | 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| PV | 0.485 ** | 0.501 ** | 0.470 ** | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| CT | 0.476 ** | 0.505 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.636 ** | 1 | -- | -- |

| EPI | 0.515 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.533 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.542 ** | 1 | -- |

| SCS | 0.436 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.524 ** | 0.569 ** | 0.453 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable: Perceived Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 30 June 2025 Time: 23:47 | ||||

| Sample: 1270 | ||||

| Included observations: 270 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| C | 4.410212 | 0.225781 | 19.53315 | 0.0000 |

| Age | −0.156387 | 0.043788 | −3.571491 | 0.0004 |

| Monthly consumption level | −0.534004 | 0.068891 | −7.751400 | 0.0000 |

| Usefulness of teaching content | 0.190705 | 0.038140 | 5.000153 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.567998 | Mean dependent var | 3.520988 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.563126 | S.D. dependent var | 0.820138 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.542082 | Akaike info criterion | 1.627906 | |

| Sum squared resid | 78.16494 | Schwarz criterion | 1.681216 | |

| Log likelihood | −215.7673 | Hannan-Quinn criter. | 1.649313 | |

| F-statistic | 116.5794 | Durbin-Watson stat | 1.832119 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

| Dependent Variable: Course Trust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 1 July 2025 Time: 00:00 | ||||

| Sample: 1270 | ||||

| Included observations: 270 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| C | 4.571563 | 0.249943 | 18.29042 | 0.0000 |

| Age | −0.147845 | 0.044688 | −3.308377 | 0.0011 |

| Monthly consumption level | −0.629257 | 0.071773 | −8.767273 | 0.0000 |

| Teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods | 0.176540 | 0.042075 | 4.195784 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.591703 | Mean dependent var | 3.446296 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.587098 | S.D. dependent var | 0.862199 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.554027 | Akaike info criterion | 1.671498 | |

| Sum squared resid | 81.64771 | Schwarz criterion | 1.724808 | |

| Log likelihood | −221.6523 | Hannan-Quinn criter. | 1.692905 | |

| F-statistic | 128.4954 | Durbin-Watson stat | 2.065585 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

| Dependent Variable: Examination Preparation Intention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 1 July 2025 Time: 00:06 | ||||

| Sample: 1270 | ||||

| Included observations: 270 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| C | 3.761809 | 0.262486 | 14.33146 | 0.0000 |

| Age | −0.255389 | 0.049280 | −5.182362 | 0.0000 |

| Monthly consumption level | −0.304632 | 0.082676 | −3.684663 | 0.0003 |

| The moderate difficulty of examination | 0.287768 | 0.043966 | 6.545274 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.510917 | Mean dependent var | 3.492593 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.505401 | S.D. dependent var | 0.886674 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.623577 | Akaike info criterion | 1.908016 | |

| Sum squared resid | 103.4337 | Schwarz criterion | 1.961326 | |

| Log likelihood | −253.5821 | Hannan-Quinn criter. | 1.929423 | |

| F-statistic | 92.62516 | Durbin-Watson stat | 1.646767 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

| Dependent Variable: Course satisfaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 30 June 2025 Time: 22:28 | ||||

| Sample: 1270 | ||||

| Included observations: 270 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| C | 0.390187 | 0.161029 | 2.423089 | 0.0161 |

| Perceived value | 0.370156 | 0.069221 | 5.347417 | 0.0000 |

| Course trust | 0.321658 | 0.062408 | 5.154145 | 0.0000 |

| Examination preparation intention | 0.191889 | 0.056100 | 3.420462 | 0.0007 |

| R-squared | 0.592295 | Mean dependent var | 3.472222 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.587696 | S.D. dependent var | 0.878368 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.564008 | Akaike info criterion | 1.707207 | |

| Sum squared resid | 84.61588 | Schwarz criterion | 1.760517 | |

| Log likelihood | −226.4729 | Hannan-Quinn criter. | 1.728614 | |

| F-statistic | 128.8106 | Durbin-Watson stat | 2.018525 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

| Path | Effect Types | Effect Value | 95% Confidence Interval | p | Effectiveness Ratio | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Limit | Lower Limit | ||||||

| Teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods course trust students’ course satisfaction | Total effect | 0.5004 | 0.4112 | 0.5895 | <0.001 | -- | Supported |

| Direct effect | 0.2149 | 0.1253 | 0.3049 | <0.001 | 42.9% | ||

| Indirect effect | 0.2854 | 0.2206 | 0.3487 | <0.001 | 57.1% | ||

| Moderate difficulty of examination students’ examination preparation intention students’ course satisfaction | Total effect | 0.4981 | 0.4129 | 0.5833 | <0.001 | -- | Supported |

| Direct effect | 0.2711 | 0.1793 | 0.3630 | <0.001 | 54.4% | ||

| Indirect effect | 0.2270 | 0.1473 | 0.3085 | <0.001 | 45.6% | ||

| Number | Research Hypothesis | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| H1a | Usefulness of teaching content positively influences students’ perceived value. | Supported |

| H1b | Teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods have a positive impact on course trust. | Supported |

| H1c | Moderate difficulty of examination positively influences examination preparation intention. | Supported |

| H2a | Perceived value positively influences students’ course satisfaction. | Supported |

| H2b | Course trust positively promotes students’ course satisfaction. | Supported |

| H2c | Examination preparation intention positively promotes students’ course satisfaction. | Supported |

| H3a | Course trust mediates the relationship between teachers’ teaching attitudes and methods and students’ course satisfaction. The stronger the course trust, the stronger the positive relationship between the two. | Supported |

| H3b | Examination preparation intention mediates the relationship between moderate difficulty of examination and students’ course satisfaction. The stronger the examination preparation intention, the stronger the positive relationship between the two. | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, Y.; Zhang, N. Research on the Effect of Economics and Management Major Teachers’ Teaching on Students’ Course Satisfaction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198755

Zeng Y, Zhang N. Research on the Effect of Economics and Management Major Teachers’ Teaching on Students’ Course Satisfaction. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198755

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Youzhi, and Ning Zhang. 2025. "Research on the Effect of Economics and Management Major Teachers’ Teaching on Students’ Course Satisfaction" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198755

APA StyleZeng, Y., & Zhang, N. (2025). Research on the Effect of Economics and Management Major Teachers’ Teaching on Students’ Course Satisfaction. Sustainability, 17(19), 8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198755