Abstract

Driven by China’s “dual carbon” strategy, concerns about channel fairness and green investment have become key frontier issues in supply chain management. This study focuses on a two-tier supply chain under a low-carbon background and innovatively incorporates both fairness concerns and green investment perspectives. It systematically explores the impact mechanisms of fairness concern coefficients and green investment levels on channel pricing and profit distribution across four scenarios: information symmetry vs. asymmetry and the presence vs. absence of channel encroachment. The simulation results reveal the following: (1) Under information symmetry and without channel encroachment, an increase in the retailer’s fairness concern significantly enhances its bargaining power and profit margin, while the supplier actively adjusts the wholesale price to maintain cooperation stability. (2) Channel encroachment and changes in information structure intensify the nonlinearity and complexity of profit distribution. The marginal benefit of green investment for supply chain members shows a diminishing return, indicating the existence of an optimal investment range. (3) The green premium is predominantly captured by the supplier, while the retailer’s profit margin tends to be compressed, and order quantity exhibits rigidity in response to green investment. (4) The synergy between fairness concerns and green investment drives dynamic adjustments in channel strategies and the overall profit structure of the supply chain. This study not only reveals new equilibrium patterns under the interaction of multidimensional behavioral factors but also provides theoretical support for achieving both economic efficiency and sustainable development goals in supply chains. Based on these findings, it is recommended that managers optimize fairness incentives and green benefit-sharing mechanisms, improve information-sharing platforms, and promote collaborative upgrading of green supply chains to better integrate social responsibility with business performance.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of online retail has created numerous opportunities for suppliers. Besides the traditional resale channels through retailers, they can establish their own sales channels and directly sell products to end consumers, which is often referred to as “supplier channel encroachment” [1,2]. In practice, upstream suppliers can adopt various forms to introduce direct sales channels, such as company-owned franchises, factory outlets, online stores, etc. Currently, more and more suppliers choose to sell products directly through their own official websites, e-commerce platforms, and direct stores. Nike implemented the “Direct-to-Consumer Acceleration Program” in 2020, selling directly through official websites, apps, and flagship stores, reducing reliance on third-party retailers. According to Nike’s FY2023 annual report, Nike Direct revenue reached USD 21.3 billion, accounting for approximately 41.6% of total revenue (USD 51.2 billion), representing an increase of about 50% compared with its share in FY2017. Moutai and Wuliangye, among other liquor enterprises, directly reach consumers through “cloud commerce platforms” and direct stores. The sales volume of Moutai’s iMoutai platform exceeded CNY 20 billion in 2024, accounting for 18% of the total revenue. This trend has become increasingly evident with the popularity of e-commerce and digital marketing, not only changing the traditional supply chain structure but also posing new challenges and requirements for middlemen and retailers. Nike’s DTC strategy has led to channel conflicts. Retailers, due to Nike’s priority in ensuring direct sales channel supplies, have seen a 12% increase in offline store out-of-stock rates. Its wholesale business revenue decreased by 2% in 2023, and the sales of core retailers decreased by 15–20%. Meanwhile, the direct sales model of Moutai, Wuliangye, and other liquor enterprises has impacted retailers, with 60% of distributors experiencing inventory accumulation and a 52.1% decrease in sales in 2024, as well as a 68.8% decrease in average transaction value. Distributors protested against the factory’s “quantity control and price guarantee” policy, resulting in terminal price discrepancies. In 2024, the wholesale price of Wuliangye was 15% lower than the guidance price. This highlights the urgent need for practitioners to better understand how to manage these conflicts and develop strategies that ensure a more balanced and efficient cooperation model between suppliers and retailers. By optimizing pricing, fairness mechanisms, and information-sharing systems, they can reduce conflicts and enhance long-term supply chain stability. In this context, retailers’ concerns about fairness have also gradually increased. The cooperation model between suppliers and retailers urgently needs to be optimized to balance the interests of both parties and reduce potential conflicts.

In the operation of a dual-channel supply chain, retailers often need to invest more in human resources, equipment, and technology to enhance channel efficiency, thus incurring higher operational costs. If manufacturers “free ride” in the direct sales channel and do not bear the corresponding costs of the additional investments in the retail sector, it will trigger retailers’ concerns about fairness. Such concerns not only relate to the reasonable distribution of channel profits but also pose higher requirements for the sustainable development of the entire supply chain. To resolve the conflicts of interest caused by uneven cost-sharing, green cooperation has emerged as a key approach to addressing supply chain complexity and enhancing sustainability. By jointly promoting green investment, all parties in the supply chain can not only improve overall operational efficiency but also effectively reduce environmental impact, thereby achieving dual value growth in economic and ecological benefits. Take Apple as an example. It collaborates with upstream and downstream partners in its global supply chain to set carbon neutrality goals, and through measures such as using recycled materials, optimizing packaging design, and improving energy utilization efficiency, it drives the green transformation of the entire network. Alibaba, relying on Cainiao Network, jointly promotes environmentally friendly packaging and green delivery solutions with logistics partners, effectively reducing carbon emissions. This green cooperation model of sharing costs and creating value not only helps to alleviate the conflicts of interest between suppliers and retailers but also provides strong support for building a sustainable dual-channel system. However, for suppliers who are launching direct sales channels for the first time, due to the lack of complete consumer demand information and the need to pay high channel construction costs, they still need to be cautious in strategic planning to ensure that they pursue green benefits while maintaining the stability of market expansion. Moreover, external carbon reduction schemes, such as carbon taxes and cap-and-trade mechanisms, also play a crucial role in shaping firms′ low-carbon strategies. Recent studies show that current carbon tax levels are often insufficient to directly induce a circular economy transition, but they affect the balance between environmental and economic objectives, thereby influencing green investment decisions (Panza & Peron, 2025) [1]. Similarly, carbon tariffs may fail to incentivize remanufacturing because costs can be passed on to consumers, whereas carbon taxes increase the marginal cost of emissions and indirectly affect exporters′ willingness to reduce emissions (Li et al., 2024) [2]. Therefore, this study provides practitioners with crucial insights on how to optimize supply chain cooperation under the dual pressures of green investments and fairness concerns. By establishing fair cost-sharing mechanisms and green cooperation models, all parties in the supply chain can better align their interests, reduce conflicts, and improve overall operational efficiency and sustainability.

2. Literature Review

This paper investigates supplier encroachment and fairness concerns within the context of green and sustainable supply chains, with particular attention to the influence of information structures and behavioral preferences on strategic decision-making. To provide a comprehensive theoretical foundation, we review the relevant literature from three key perspectives: (1) the effects of supplier encroachment strategies on supply chain performance, (2) the role of fairness concerns in channel coordination and cooperation, and (3) the relationship between fairness preferences and green investment behaviors in sustainable supply chains. These three strands of research offer valuable insights for understanding the complex dynamics of dual-channel systems under sustainability considerations.

2.1. Supplier Encroachment from the Perspective of Dual Effects

Existing studies have examined the dual effects of supplier encroachment, yielding different conclusions through both theoretical models and empirical analyses. Liu et al. (2006) and Zhang et al. (2021), under the assumption of symmetric information in a two-stage dual-channel model, found that supplier entry into the direct channel tends to significantly reduce the retailer’s profit due to intensified horizontal competition and may negatively affect overall supply chain efficiency [3,4]. In contrast, Sun et al. (2019, 2021) introduced cost heterogeneity and showed that when the cost of direct sales is sufficiently low, supplier encroachment can improve the supplier’s profit and even generate marginal benefits for the retailer under high-cost conditions [5,6]. These findings suggest that cost structures and market conditions play a moderating role in shaping the outcomes of encroachment strategies. Arya et al. (2007) further demonstrated that when accounting for double marginalization, a mixed channel strategy could lead to Pareto improvements for both parties [7,8,9,10,11,12]. However, the low-carbon transformation adds a new dimension to these dynamics. Through green investments, suppliers can enhance product value, strengthen market competitiveness, and shift the supply chain power balance. This advantage allows them to charge higher prices and gain more resources for channel encroachment, potentially increasing direct sales priority and intensifying profit negotiation pressures for retailers. This shift is supported by existing studies on green supply chains, such as those by Huang et al. (2018), who demonstrated that green investments could enhance product quality and competitiveness, leading to greater market power for suppliers [13]. Moreover, Shao et al. (2021) argued that the increase in fairness concerns due to green investment pressures can lead suppliers to adjust their strategies to maintain cooperation with retailers [14]. Likewise, Cao and Mei (2022) showed that fairness concerns and risk aversion jointly shape green supply chain decisions, directly affecting product greenness and profit distribution [15]. These studies reinforce the view that supplier encroachment must be analyzed under the dual influence of behavioral preferences and sustainability considerations.

Nevertheless, most of the existing literature concentrates on static factors, such as cost and product quality, while less attention has been given to the influence of information structures on the outcomes of supplier encroachment. Building upon these foundations, the present study extends the analysis by incorporating both symmetric and asymmetric information conditions alongside fairness concerns. Using an evolutionary game framework, it explores how repeated strategic interactions may evolve under different informational settings and how these dynamics affect channel behavior and coordination. This approach aims to provide new insights into the interaction between information asymmetry, behavioral preferences, and supply chain strategies under sustainability considerations.

2.2. Fairness Concerns and Supply Chain Coordination

Although some studies have introduced product durability [16], advertising cost-sharing [17], private labels [18], strategic inventory [19,20], and moderate product differentiation [21] into two-stage dual-channel models, few have integrated both information structure (especially asymmetry) and fairness concerns in a unified framework under a low-carbon context. The existing research has shown that retailers, who often bear higher operational costs, may perceive supplier-led direct sales expansion as a form of free-riding, which triggers fairness-driven responses, such as reducing order quantities or engaging in price competition [22,23]. In a low-carbon transformation, these fairness concerns may be amplified, as suppliers leveraging green investments can strengthen their bargaining power, potentially increasing perceived inequities in profit distribution [13]. Conversely, fairness preferences can motivate suppliers to adapt their encroachment strategies to sustain long-term cooperation [23]. Lin et al. (2024) further showed that properly addressed fairness concerns—through service investments or contract mechanisms—can align with coordination goals and enhance supply chain stability [24]. In the context of remanufacturing, Zhang (2022) analyzed how fairness concerns in a reverse supply chain affect strategic behavior and utility under a game-theoretic framework [25]. Additionally, Zhang (2019) modeled how a retailer′s fairness concern influences the manufacturer’s decision to adopt a green manufacturing strategy in a dual-channel setting, highlighting the role of government subsidies and fairness in promoting sustainability [26]. However, in a green supply chain, fairness concerns and low-carbon strategies interact dynamically, influencing both pricing and channel coordination [14].

While these studies highlight the behavioral dimension of channel relationships, most rely on static fairness assumptions and symmetric information settings. Building upon these insights, the present study considers both symmetric and asymmetric information conditions and incorporates dynamic fairness concerns into an evolutionary game framework. This approach allows for the examination of how fairness preferences evolve over time through repeated interactions and how information asymmetry—such as incomplete knowledge of cost structures or green investment efforts—affects negotiation strategies, contract design, and coordination outcomes. By doing so, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of fairness-driven dynamics in dual-channel supply chains.

2.3. Fairness Preferences and Green Investment in Sustainable Supply Chains

In recent years, as sustainability and the low-carbon transformation have become increasingly central, scholars have gradually incorporated fairness concerns into green supply chain research to explore how fairness preferences affect green investment decisions and carbon reduction performance. Huang et al. (2018), by introducing retailers’ fairness preferences into a dual-channel model, found that such preferences may contribute to improving the quality level of green products manufactured by suppliers and enhance both economic and environmental performance of the supply chain [13]. Similarly, Shao et al. (2021) argued that a higher level of fairness concern among retailers tends to strengthen suppliers’ willingness to invest in green transformation and also boosts the market acceptance of green products [14]. From the perspective of incentive mechanisms, Zou et al. (2024) suggested that fairness preferences could serve as an endogenous motivational factor, encouraging supply chain members to engage in joint green investment and benefit sharing [27].

However, alternative views have also been presented. Li et al. (2021) found that when suppliers place excessive emphasis on the fairness of profit distribution, their willingness to invest in green technology may decline, potentially leading to reduced overall carbon reduction performance [28]. Jian et al. (2021), using an evolutionary game model, suggested that while moderate fairness concerns can promote collaborative green innovation, overly strong fairness preferences may trigger adverse reactions, undermining long-term cooperation [29]. Ye et al. (2021) further distinguished between the fairness concerns of suppliers and retailers, arguing that suppliers, being more sensitive to their own returns, may delay green transformation efforts, whereas moderate fairness preferences from retailers could play a more constructive role in building long-term low-carbon partnerships [30]. Fernández et al. (2025) provided a broader behavioral–environmental nexus perspective, analyzing how fairness dynamics interact with environmental outcomes in digitalized circular economy contexts [31].

In the low-carbon context, green investments not only incur additional costs but also reshape the power structure in the supply chain, which may amplify fairness concerns and affect cooperation incentives. This dynamic interaction was highlighted by Jian et al. (2021), who showed that fairness concerns in green closed-loop supply chains can significantly influence pricing, investment strategies, and coordination effectiveness under sustainability goals [29]. Yet, most prior research addresses these issues in a static and unilateral manner, often under symmetric information. To bridge this gap, the present study considers differences in information structure and employs an evolutionary game framework to examine how fairness concerns and green investment strategies evolve under incomplete information, focusing on the conditions that enable stable and mutually beneficial green cooperation.

2.4. Research Gap

A review of the literature shows that, although fairness concerns in supplier channel encroachment have been widely examined, few studies systematically integrate green investment and information structure differences under the “dual carbon” goals. The low-carbon transformation can alter supply chain power dynamics through green investment, potentially amplifying or easing fairness concerns. These effects intensify when suppliers engage in channel encroachment, as the allocation of the “green premium” may heighten perceived inequities.

Most existing studies analyze fairness concerns under the assumption of symmetric information, whereas, in reality, suppliers and retailers often operate under asymmetric information due to differences in market positions and access to demand data. Evolutionary game theory offers a suitable analytical tool for modeling the repeated strategic interactions of supply chain members, particularly under conditions of information asymmetry and bounded rationality, making it well suited to studying how fairness concerns and green investment decisions evolve in a low-carbon supply chain. Therefore, this study incorporates the perspectives of green investment and information asymmetry into the research on supplier channel encroachment and fairness concern, enriching the existing theoretical framework and providing new theoretical support for the coordination of green supply chains.

Based on these gaps, this paper investigates the following: (1) how the fairness concern coefficient affects the interests of suppliers and retailers under both symmetric and asymmetric information; (2) how the level of green investment influences the interests of both parties under different information structures; and (3) under information asymmetry, the conditions under which suppliers and retailers can achieve a win–win outcome. To address these questions, four scenarios are constructed, namely, the supplier non-encroachment model (SN) under symmetric information, the supplier encroachment model (SE) under symmetric information, the supplier non-encroachment model (AN) under asymmetric information, and the supplier encroachment model (AE) under asymmetric information. For each scenario, a game-theoretic model is developed and solved to identify optimal strategies that balance economic performance and sustainable development objectives.

3. Model Description and Assumptions

3.1. Model Description

This study constructs a supply chain system, composed of suppliers and retailers with green emission reduction investment cooperation, and investigates the influence mechanism of fairness concern and green investment level on the channel encroachment strategy of suppliers under both information symmetry and information asymmetry. In line with many dual-channel supply chain studies (e.g., Li et al., 2014; Ha et al., 2022), we assume that only retailers exhibit fairness concerns, while suppliers are fairness-neutral in their strategic decision-making [23,32]. This modeling choice is based on the observation that downstream retailers often bear higher operational costs and are more sensitive to perceived inequities in profit distribution, especially when suppliers engage in direct sales. Retailers are typically the primary recipients of potential channel conflicts, making fairness concerns a more salient behavioral factor for them. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that in real low-carbon supply chains, dominant suppliers may also consider fairness in profit distribution to maintain long-term cooperation stability, particularly when green investment and the “green premium” are involved. Exploring dual fairness concerns would be a valuable extension for future research.

First, the information transmission mechanism of retailers needs to be systematically analyzed. The fairness concern behavior of retailers directly affects the authenticity of their information sharing, which, in turn, affects the decisions of suppliers. This influence mechanism needs to be deeply explored through game theory. Therefore, we construct a game model to systematically explore the impact of the fairness concern coefficient on the channel encroachment strategy of suppliers and the profits of both parties.

Second, there is asymmetry in market demand information. The complexity and uncertainty in the market environment make it difficult for upstream suppliers to accurately grasp the real market demand situation. Although suppliers can obtain demand information through retailers, the fairness concern behavior of retailers will affect the accuracy of their information sharing, thereby affecting the channel encroachment decision of suppliers. Therefore, we conduct research under both information symmetry and information asymmetry scenarios to make this study more practical.

Third, the green investment level in the supply chain has significant research value. Under the dual effects of information asymmetry and retailer fairness concern, the green investment cooperation between suppliers and retailers becomes a key factor in regulating the supply chain relationship and influencing the channel encroachment decision of suppliers. Moreover, the green investment level not only reflects the environmental responsibility of enterprises but also affects the channel encroachment strategy choice of suppliers. An increase in green investment level enhances the market attractiveness of products, thereby motivating suppliers to take channel encroachment actions; on the other hand, the green investment level directly affects the profit performance of suppliers and retailers. Therefore, we consider the green cost-sharing coefficient and the green investment level coefficient of suppliers and retailers in the game model.

Furthermore, under channel encroachment, the retailer’s fairness reference is assumed to be the supplier’s direct-channel profit rather than its total profit. This assumption aligns with fairness-preference theory and supply chain fairness studies [33,34], which suggest that decision makers anchor fairness concerns to the outcomes of the most salient competitor. Since the supplier’s direct channel competes directly with the retailer, it becomes the most relevant benchmark.

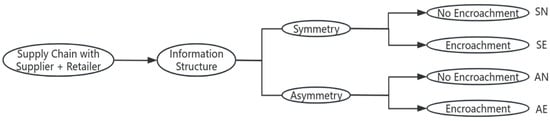

Based on the above reasons, this study designs four game scenarios: no channel encroachment by suppliers under symmetric information (SN), channel encroachment by suppliers under symmetric information (SE), no channel encroachment by suppliers under asymmetric information (AN), and channel encroachment by suppliers under asymmetric information (AE) as shown in Figure 1. Through optimal decision analysis and comparative research, we systematically explore the impact of retailer fairness concern, demand information symmetry, and green investment on the channel encroachment strategy of suppliers. This research framework provides a theoretical decision-making basis for supply chain management and promotes the sustainable development of the supply chain. In addition, to explicitly link green investment with environmental outcomes, Assumption 5 introduces an emissions function that connects the level of green input to abatement performance, and it can also accommodate policy mechanisms, such as carbon taxes and cap-and-trade schemes.

Figure 1.

Scenario map of the four supply chain cases.

3.2. Model Assumptions

A supply chain composed of a profit-oriented supplier and a retailer is established under both information symmetry and asymmetry scenarios. In this chain, the retailer and the supplier cooperate on green investment, and the retailer has a sense of fairness concern. The manufacturer decides whether to encroach on the channel. This study examines the impact of the fairness concern coefficient and the level of green investment on the supplier’s channel encroachment strategy and the profits of both parties.

Assumption 1.

Supply chain production cost and sales cost. According to the research of Li et al. (2014) [32], this paper standardizes the production cost of the supplier and the sales cost of the retailer to 0. Considering that the efficiency of the supplier in the retail business may be lower than that of the retailer, this paper assumes that the sales cost per unit of product for the supplier selling directly to consumers is d.

Assumption 2.

Consumer inverse demand function. Referring to the studies by HA et al. (2022) [35], HSU et al. (2019) [36], and CAO et al. (2022) [37], consumer demand follows a linear downward-sloping inverse demand function, , where > 0, b > 0, r > 0, represents the potential market demand size; the larger a is, the greater the potential market demand; b is the sensitivity coefficient of sales volume to price; Q is the total sales volume of the product; e is the manufacturer’s green input level; and r is the sensitivity coefficient of consumers to the green input level of the product. Here, (when there is no supplier encroachment), and (when there is supplier encroachment). Under information asymmetry, it is assumed that the retailer has full knowledge of the actual market demand, while the supplier only knows its probability distribution [23,32]. In practice, retailers may transmit demand-related information through observable signals, such as order volumes, pricing strategies, and promotional intensity [33]. Fairness concerns may influence the authenticity and completeness of this information transmission: when the fairness concern coefficient is high, retailers may strategically distort signals to protect their profit share or strengthen bargaining power [38,39]. This, in turn, could lead suppliers to misestimate market potential, affecting their willingness to engage in channel encroachment and altering their optimal green investment levels. For example, understated demand signals might discourage encroachment or limit green investment, whereas exaggerated signals could induce over-encroachment and excessive green input. While such signaling behaviors are not explicitly modeled in this study, incorporating strategic information transmission under fairness concerns represents a meaningful extension for future research.

Assumption 3.

Market distribution. Reference assumes that the market distribution information held by the supplier is an uncertain two-point random distribution function. When , the probability is , where ; when , the probability is . During this period, the expected market demand and variance are, respectively, and . Since the same product is sold through different sales channels, the potential market size remains unchanged at v. To ensure that the order quantity in the supply chain is positive, it is assumed that . As the products sold through the two sales channels of the supplier are the same, the supplier’s channel encroachment behavior will not affect the change in the total market demand v.

Assumption 4.

Green investment costs are shared proportionally. In the green supply chain cooperation, the supply chain entities will share the green investment costs proportionally. A reasonable cost-sharing mechanism is crucial for maintaining the cooperative relationship among members. This paper assumes that the supplier and the retailer share the green investment costs in the same proportion, mainly considering fairness and incentive compatibility. Cachon and Lariviere’s research indicates that average sharing, as a simple and fair mechanism, helps enhance the sustainability of cooperation and reduces conflicts caused by uneven responsibility allocation [40]. Therefore, sharing green investment costs proportionally not only has theoretical rationality but also conforms to management practices in reality.

Assumption 5.

Environmental linkage assumption. To explicitly connect green input and abatement, we define an emissions function with , , capturing diminishing marginal abatement. Without altering optimization or simulations (for reporting only), we set:

where is baseline emissions () and are scaling parameters. In each scenario (SN/SE/AN/AE), keeping the already-optimized e, we report alongside profits: abatement and abatement rate /.

In the decision-making sequence of the supply chain, before the start of the sales season, the supplier first sets the wholesale price w. After receiving the wholesale price w, the retailer decides to order a quantity of products from the supplier. After receiving the retailer’s order quantity, the supplier, after judging the actual market distribution situation, decides whether to open a direct sales channel to encroach on the traditional market. The sales volume of the direct sales channel is . In the mode where the supplier does not conduct channel encroachment, there is only a single retail channel at this time, so the total sales volume of the product is ; in the mode where the supplier conducts channel encroachment, there are two channels, namely, the retail channel and the supplier’s direct sales channel, at this time, so the sales volume of the product is . After the start of the sales season, the retailer and the supplier sell to consumers at the market clearance price p.

For supply chain entities with a concern for fairness, their utility depends on the profits they obtain and the gap from the fairness reference. For ease of calculation, without loss of generality, this paper, referring to the research of Du et al. [41], uses a linear form to represent the profit of supply chain decision-making entities. Following Fehr and Schmidt (1999) and Cui et al. (2007), we adopt the disadvantageous inequity aversion form, which captures the situation where the retailer’s utility decreases when its profit is lower than the supplier’s [33,34]. Accordingly, the retailer’s utility function is specified as:

where is the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient. This form is chosen because, in the low-carbon supply chain scenarios considered here, suppliers—being dominant channel members—rarely earn less than retailers; hence, advantageous inequity aversion is negligible.

Although in real low-carbon supply chains, suppliers may also pay attention to the fairness of profit distribution (e.g., when formulating wholesale prices and direct sales strategies to maintain long-term cooperation), we intentionally omit supplier fairness concerns for two reasons: (1) Cui et al. (2007) show that downstream members’ fairness reactions are more pronounced and have stronger behavioral impact than upstream members’ in asymmetric power structures [33] and (2) excluding supplier fairness keeps the analytical model tractable and isolates the marginal effect of retailer fairness on green investment and encroachment strategies. This simplifying assumption does not qualitatively alter the main comparative statics, but future research could relax it to explore bilateral fairness concerns.

The corresponding parameters of this paper are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notation table.

4. Supply Chain Decision-Making Considering Fairness Concerns Under Information Symmetry

Firstly, this paper explores supply chain decisions under information symmetry. In a supply chain where the retailer has fairness concerns and information is symmetric, both the supplier and the retailer are aware of the true market demand. At this stage, the situations where the supplier does not encroach and where the supplier encroaches under information symmetry are, respectively, denoted by the superscripts “SN” and “SE”.

4.1. No Supplier Encroachment (SN)

In this subsection, we first explore the situation where the supplier does not encroach. Under information symmetry, if the retailer has a sense of fairness and the supplier does not enter the market, due to the complete symmetry of information, the decision-making sequence of the supply chain is as follows: the supplier sets the wholesale price w; the retailer, who has access to market information, determines its order quantity based on maximizing its own profit and, finally, sells to consumers at the price . At this time, the profits of the retailer and the supplier are, respectively:

By using the reverse solution method, the optimal order quantity for the retailer and the optimal wholesale price for the supplier are first calculated. Substituting these values into the solution yields Theorem 1.

Theorem 1.

In the SN scenario, the optimal wholesale price of the supplier, the optimal order quantity of the retailer, and the optimal profit of the decision-making entity are, respectively:

From Theorem 1, it can be known that the optimal decision is related to the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient and the level of green investment. Meanwhile, the influence of the fairness concern coefficient on the optimal decision and the retailer can be obtained, as shown in Proposition 1.

Proposition 1.

; ; ; ; .

According to Proposition 1, when information is symmetric and the supplier does not conduct channel encroachment, the supplier’s optimal wholesale price w and optimal profit π decrease as the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient θ increases; the retailer’s profit π increases with the growth of the fairness concern coefficient θ, but the retailer’s market clearing price p and order quantity (sales volume) q are not affected by the fairness concern coefficient. In the realistic situation where information is symmetric and the supplier does not implement channel encroachment, the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient has a significant impact on the supplier’s wholesale price and profit. Specifically, as the retailer’s fairness concern increases, the supplier’s optimal wholesale price and profit both show a downward trend. The formation of this phenomenon mainly stems from the supply chain members’ cognition and behavioral adjustments regarding fairness. When the retailer’s fairness concern intensifies, they pay more attention to the rationality of profit distribution and the protection of their own interests. To maintain a long-term cooperative relationship with the retailer and avoid channel conflicts and cooperation breakdowns caused by unfair profit distribution, the supplier voluntarily lowers the wholesale price to alleviate the retailer’s fairness concerns, thereby sacrificing some of its own profits. Meanwhile, the retailer’s market clearing price and order quantity are basically unaffected by the fairness concern coefficient, indicating that the retailer’s pricing and purchasing decisions are mainly determined by market demand and price elasticity rather than fairness concern factors. However, the retailer’s profit increases with an increase in the fairness concern coefficient because the supplier’s reduction in the wholesale price directly reduces the retailer’s procurement cost and expands its profit margin.

This result indicates that fairness concern is not only an important behavioral norm in channel relationships but can also promote coordination and cooperation among supply chain members, alleviate the double markup problem in traditional channels, and thereby enhance the overall efficiency of the supply chain.

Meanwhile, the impact of the green input level on the optimal decision and the supplier and retailer can be obtained, as shown in Proposition 2.

Proposition 2.

- (1)

- ; ; ;

- (2)

- , , ; otherwise, .

From Proposition 2, it can be known that in the case of information symmetry and no channel encroachment by suppliers, the level of green investment and the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient have a significant impact on the pricing decisions and profit distribution of supply chain members. Specifically, as the level of green investment increases, the wholesale price of the supplier and the retailer’s order quantity (sales volume) both show an upward trend, while the retailer’s market clearing price decreases accordingly. At the same time, the profits of both the supplier and the retailer are jointly affected by the level of green investment in a nonlinear manner: Firstly, when the fairness concern coefficient is low and the level of green investment is below a certain critical threshold, the profits of both parties increase with the increase in the level of green investment; however, when the level of green investment exceeds this threshold, profits decrease. As the level of green investment increases, the supplier enhances the environmental attributes and quality image of the product by adopting more environmentally friendly technologies and processes, thereby increasing the product’s market competitiveness and consumer recognition. This enables the supplier to set a higher wholesale price, and the retailer adjusts the market clearing price to reflect the added value of the product, thereby increasing the retailer’s order quantity. This conforms to the general manifestation of the green product premium effect in the market. Secondly, the benefits brought by green investment can effectively increase the profits of both parties, but when the level of green investment exceeds a certain critical threshold, the input cost rises rapidly, and the marginal cost exceeds the marginal benefit, leading to a decrease in profits. This inverted U-shaped trend in profit changes reflects the law of diminishing marginal returns of green investment.

4.2. Supplier Encroachment (SE)

Under information symmetry, if the retailer has fairness concerns and the supplier adopts an encroachment strategy, the decision-making sequence of the supply chain is as follows: Similar to the SN strategy, the retailer and the supplier first negotiate to determine the wholesale price w. Then, the retailer places an order with the supplier. Subsequently, the supplier formulates the production strategy for the direct sales channel. Generally, the supplier’s approach to launching a direct sales channel usually involves opening a direct sales store or conducting e-commerce operations, which includes store costs, sales staff employment costs, social media account operation costs, etc. Therefore, the direct sales cost is relatively high. To simplify the calculation, it is assumed that the unit direct sales cost set by the supplier is an exogenous fixed variable d. Finally, consumers purchase the product at the market clearing price , and thus, the supplier and the retailer obtain profits.

At this point, as suppliers encroach on the market, when retailers exhibit fair concern behavior, the retailer’s fairness reference point will no longer be the overall profit of the supplier but the profit of the invading channel. At this time, the profits of the retailer and the supplier are, respectively:

Theorem 2 can be obtained through the reverse solution method.

Theorem 2.

Under the SE strategy, the optimal direct sales quantity of the supplier, the optimal order quantity of the retailer, the optimal wholesale price of the supplier, and the optimal profit function of the decision-making subject are, respectively:

According to Theorem 2, the relationships between the optimal wholesale price, the optimal order quantity of the retailer, the optimal direct sales volume of the supplier, and the retailer’s fairness concern can be further obtained, as shown in Proposition 3.

Proposition 3.

; ; ; when , otherwise, ; when , otherwise, ; when otherwise, . is the root of .

Proposition 3 indicates that in a situation where information is symmetric and there is channel encroachment by the supplier, the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient has a complex and profound impact on the pricing, ordering decisions, and profit distribution of all parties in the supply chain. Specifically, as the fairness concern coefficient increases, the sales volume of the supplier’s direct sales channel shows a downward trend. The supplier’s wholesale price and profit are nonlinearly affected by the fairness concern coefficient: (1) When the fairness concern coefficient is low, the wholesale price is positively correlated with the fairness concern coefficient; otherwise, it is negatively correlated. (2) When the fairness concern coefficient is higher than the threshold, the supplier’s profit is positively correlated with the fairness concern coefficient; otherwise, it is negatively correlated. The retailer’s market clearing price increases with an increase in the fairness concern coefficient, but its order quantity (sales volume) shows a downward trend. In addition, the retailer’s profit is also nonlinearly affected by the fairness concern coefficient: when the fairness concern coefficient is higher than the threshold, the retailer’s profit is positively correlated with the fairness concern coefficient; otherwise, it is negatively correlated. Specifically, an increase in the fairness concern coefficient means that the retailer is more concerned about the profit gap between itself and the supplier, which prompts the supplier to balance between direct sales and wholesale. If the retailer’s fairness concern is low, the supplier can increase its profit by raising the wholesale price—at this time, both parties still focus on maximizing efficiency, and the contradiction in profit distribution is not prominent. However, when the fairness concern gradually strengthens and exceeds a certain critical threshold, if the supplier continues to raise the wholesale price, it will face the risk of retailer resistance or reduced orders. To avoid channel conflicts, the supplier has to offer concessions, thereby causing the wholesale price and its own profit to decrease as the fairness concern further increases. At this time, the retailer’s profit benefits from the “concession” and is positively correlated with the fairness concern. At the same time, the retailer’s order quantity decreases as the fairness concern strengthens because, in the pursuit of fairness, the retailer pays more attention to profit distribution, rather than simply expanding the sales scale, and partially “actively contracts” to improve its bargaining position. Although the retail price will increase because of the supplier’s strategy adjustment, the retailer’s overall sales volume is difficult to grow simultaneously.

Proposition 4.

; ; ; ; ; when , ; otherwise, .

From Proposition 4, it can be known that under the circumstances of information symmetry and the existence of supplier channel encroachment, as the level of green investment increases, the wholesale price set by the supplier and its optimal sales volume in the direct sales channel, as well as the market clearing price of the retailer, all show an upward trend. However, the retailer’s order quantity is not sensitive to changes in green investment and remains unchanged. The retailer’s profit decreases as the level of green investment increases, while the supplier’s profit is nonlinearly affected by the level of green investment: when the level of green investment is below a certain threshold (), the supplier’s profit is positively correlated with the level of green investment; otherwise, it is negatively correlated. In reality, this conclusion reflects the real challenges in the distribution of benefits and incentive mechanisms in the green supply chain. Firstly, as the supplier increases green investment (such as the use of environmentally friendly raw materials and green technologies), consumers’ recognition of the product improves, and the market, as a whole, is willing to pay a higher premium for “green” products. This enables the supplier not only to reasonably increase the wholesale price but also to achieve higher sales volumes in the direct sales channel, and the retailer’s terminal selling price also rises accordingly. However, most of the costs brought by green investment are borne by the supplier. Although high investment can enhance the product’s attractiveness and the supplier’s premium space in the short term, the cost of investment increases at an accelerating rate with the increase in e. Therefore, the supplier’s profit will continue to benefit when the level of green investment is below a certain threshold, but it will decline after exceeding that threshold due to excessively high marginal costs. On the other hand, the reason why the retailer’s order quantity is not sensitive to green investment is that its ordering decision is mainly influenced by market demand, channel structure, and fairness concerns. Although green investment increases the product’s value, it also simultaneously raises the wholesale price and the market retail price. The demand elasticity and the retailer’s sensitivity to profit distribution keep its sales volume stable, and it does not actively expand due to simple green investment. More importantly, the benefits of the green premium are mainly controlled by the supplier. The retailer can only passively accept higher purchase prices and cost-sharing, but it cannot effectively increase its sales volume and profit space by relying on the green label, resulting in its profit continuously decreasing as the level of green investment increases.

5. Supply Chain Decision-Making Considering Fairness Concerns Under Information Asymmetry

In this subsection, the problem of the supplier’s encroachment strategy under the condition of information asymmetry and fairness concern is considered. Based on the relevant assumptions in the previous text, the retailer has a better understanding of the real market information than the supplier, while the supplier can only obtain the probability of a high-demand market distribution. Under this background, this subsection represents the supplier’s non-encroachment and encroachment strategies under information asymmetry by superscripts “AN” and “AE”, respectively.

5.1. No Supplier Encroachment (AN)

Under the non-encroaching strategy of the supplier in the context of information asymmetry, if the retailer exhibits fairness concern behavior, the decision-making sequence of the supply chain is as follows: Firstly, the supplier sets the wholesale price w based on the expected market demand it acquires. Then, the retailer determines a reasonable order quantity based on the wholesale price set by the supplier. Finally, the product is sold to consumers at the market clearing price . At this point, the profit functions of the retailer and the supplier are, respectively:

By using the reverse solution method, Theorem 3 can be obtained.

Theorem 3.

Under the AN strategy, the optimal direct sales quantity of the supplier, the optimal order quantity of the retailer, the optimal wholesale price of the supplier, and the optimal profit function of the decision-making subject are, respectively:

According to Theorem 3, the influence of the fairness concern coefficient on the optimal decision and the supplier and retailer can be obtained, as shown in Proposition 5.

Proposition 5.

When : ; ; ; ; .

Proposition 5 indicates that in the context of information asymmetry and without channel encroachment by the supplier: the supplier’s wholesale price and its profit decrease as the fairness concern coefficient increases; the retailer’s market clearing price and the retailer’s order quantity (sales volume) are not affected by the fairness concern coefficient, but its profit increases as the fairness concern coefficient increases. This is because as the retailer’s degree of fairness concern rises, the supplier, in order to maintain the channel relationship and avoid unfair profit distribution, voluntarily lowers the wholesale price, thereby leading to a decline in its profit level. This phenomenon stems from the fact that under information asymmetry, when the supplier is under the pressure of the retailer’s fairness concern, it must balance its own profit with the stability of the channel, choosing to offer concessions to alleviate the retailer’s fairness concerns and prevent the deterioration of the cooperative relationship or the intensification of channel conflicts. Meanwhile, the retailer’s market clearing price and order quantity are basically unaffected by changes in the fairness concern coefficient, indicating that the retailer’s pricing and purchasing decisions are mainly determined by market demand and price elasticity rather than fairness concern factors. However, the retailer’s profit increases as the fairness concern coefficient increases, as the supplier’s wholesale price reduction directly lowers the retailer’s procurement cost and expands its profit margin. It is worth noting that under information asymmetry, the retailer’s role as the holder of real market demand information also enables it to influence the supplier’s perception of demand through strategic signal transmission, such as adjusting order volumes or pricing, as discussed by Li et al. (2014) [32]. When the fairness concern coefficient θ is high, the retailer may deliberately understate demand to pressure the supplier into lowering wholesale prices, thereby securing a more favorable profit split, a behavior consistent with the findings of Cui et al. (2007) and Wang et al. (2019) [33,38]. Such under-reporting of demand can further reduce the supplier’s perceived market potential, discouraging channel encroachment and lowering incentives for green investment, as suggested by Xiao and Yu (2006) [39]. Although this signaling effect is not explicitly modeled in the analytical framework, it provides an important behavioral interpretation for the observed declines in wholesale prices and supplier profits as θ increases.

This result suggests that in the real supply chain, retailers can effectively enhance their bargaining power by expressing fairness concerns, which prompts suppliers to adjust wholesale prices to maintain the cooperative relationship. Meanwhile, suppliers need to balance between profit sacrifice and channel stability.

Meanwhile, the impact of the level of green investment on the optimal decision and the supplier and retailer can be obtained, as shown in Proposition 6.

Proposition 6.

- (1)

- ; ; ;

- (2)

- : when , ; otherwise ;

- (3)

- and , remains valid under all specified conditions.

Proposition 6 indicates that in the case of information asymmetry and no supplier channel encroachment, the wholesale prices of suppliers and the market clearing prices of retailers both increase as the level of green input rises, but the order quantity (sales volume) of retailers is not affected by the level of green input. The profits of both the supply chain parties vary differently under different market demands in relation to the level of green input: when the actual market demand held by retailers is greater than the expected market demand of suppliers, only when the level of green input is below the threshold, the profits of both parties are positively correlated with the green input level; when the actual market demand held by retailers is less than the expected market demand of suppliers, the profits of both parties decrease as the level of green input increases. In reality, this result reflects the challenges of green supply chain benefit distribution under the condition of information asymmetry. Increasing green input by suppliers will enhance the premium ability of products in the market, so they can raise the wholesale price, and retailers will also increase the retail price accordingly. However, since retailers have access to real demand information and are more cautious, the order quantity will not change due to green input. When the market demand is high (the actual demand held by retailers is greater than the expected demand of suppliers), moderate green input can enhance the overall profit of the channel, but once the input exceeds the threshold, the cost increase will erode the profits of both parties; when the market demand is lower than the expectation, regardless of the amount of green input, the market returns are limited, and the profits of both parties will decrease as the green input increases. This shows that green input can truly bring win–win results to the supply chain only when the market demand is sufficient and the input is moderate; if information asymmetry leads to overestimation or misjudgment of the market demand, blindly increasing green input may cause overall channel profits to be damaged. Therefore, enterprises in green supply chain decision-making should attach importance to market information sharing and real demand assessment, reasonably set the intensity of green input, and promote channel collaboration and win–win results.

5.2. Supplier Encroachment (AE)

Under the encroaching strategy of the supplier in the context of information asymmetry, the decision-making sequence of the supply chain at this time is as follows: First, the supplier sets the wholesale price w based on the expected demand. Then, the retailer, after obtaining the wholesale price, determines the order quantity to maximize its own profit based on the actual market demand. At the same time, the supplier makes the decision on the direct sales quantity by considering the expected market demand and the unit direct sales cost d. Finally, the market clearing price flows to the consumers.

Similar to the SE strategy, the retailer’s fairness concern in the case of an encroachment only focuses on the profits of the direct sales channel. At this time, the profit functions for the retailer and the supplier are, respectively:

By using the backward-solving method, Theorem 4 can be obtained.

Theorem 4.

Under the AE strategy, the optimal direct sales quantity for the supplier, the optimal order quantity for the retailer, the optimal wholesale price for the supplier, and the optimal profit function for the decision-making entity are as follows:

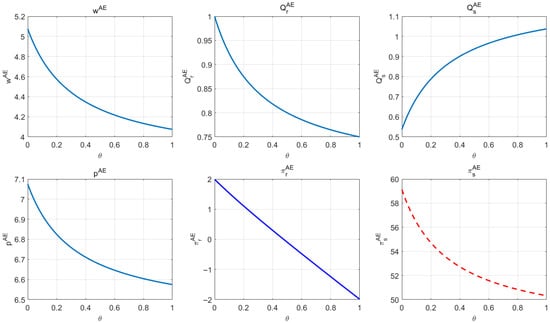

According to Theorem 4, by further exploring the relationship between each optimal decision and the fairness concern coefficient, the influence of the fairness concern coefficient on the optimal decision, as well as on the suppliers and retailers, can be obtained, as shown in Proposition 7.

Proposition 7.

; ; ; ; ; when , ; where is the root of .

Proposition 7 indicates that in the case of information asymmetry and supplier channel encroachment, when the fairness concern coefficient θ increases, the wholesale pricing and the profits of the suppliers, as well as the market-clearing prices and the order quantities (sales volumes) of the retailers, will show a monotonically decreasing trend. However, the sales volume of the supplier’s direct sales channel is positively correlated with the fairness concern coefficient. The retailer’s profits are nonlinearly affected by the fairness concern coefficient: when the fairness concern coefficient is low, the retailer’s profits are negatively correlated with the fairness concern coefficient; when the fairness concern coefficient is high, it is positively correlated. This phenomenon has a clear economic logic in reality. Firstly, as the fairness concern coefficient increases, the retailer’s sensitivity to the fairness of profit distribution increases. To alleviate the retailer’s fairness concerns, suppliers usually lower the wholesale prices to maintain the channel relationship, which directly leads to the decrease in wholesale prices and the sales volume of the supplier’s direct sales channel. The reason for the decrease in the sales volume of the supplier’s direct sales channel is that the higher fairness concern limits the space for the supplier to excessively invade the retail market through the direct sales channel to avoid intensifying channel conflicts. However, despite the decrease in wholesale prices and direct sales volume, the supplier’s profits are positively correlated with the fairness concern coefficient. This is because the supplier reduces the conflict of interests with the retailer by lowering the wholesale price, which enhances the stability of channel cooperation and the overall supply chain efficiency, thus achieving profit improvement in the long-term game. At the same time, the market-clearing price of the retailer increases with the increase in the fairness concern coefficient, reflecting the retailer’s enhanced bargaining power in channel negotiations and the pursuit of fair returns. However, the order quantity of the retailer shows a decreasing trend, mainly due to the intensified market competition caused by the supplier’s channel encroachment, which compresses the retailer’s sales space. The nonlinear response of the retailer’s profits to the fairness concern coefficient reflects the complex bargaining mechanism of channel cooperation in reality: when the fairness concern coefficient is low, the retailer’s profits decrease, possibly due to the fact that the supplier has not fully made concessions and the channel conflicts are relatively intense; when the fairness concern coefficient exceeds a certain threshold, the supplier’s willingness to make concessions and cooperate increases, and the retailer’s profits start to rise. In the case of channel encroachment under information asymmetry, strategic information transmission becomes even more critical. Retailers with high fairness concerns (large θ) may distort demand signals—through order quantities or pricing strategies—not only to protect their own profit share but also to limit the supplier’s ability to expand its direct sales channel, as highlighted by Ha et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2019) [23,38]. This behavior can cause the supplier to underestimate actual market demand, leading to more conservative encroachment decisions and potentially reducing green investment levels, as argued by Xiao and Yu (2006) [39]. Conversely, if the retailer overstates demand, it could induce over-encroachment and over-investment in green technology, both of which may result in inefficiencies.

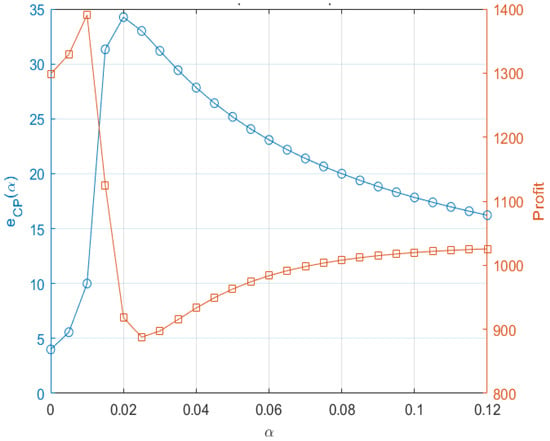

At the same time, the impact of the green input level e on the optimal decision-making and the suppliers and retailers can be obtained, as shown in Proposition 8.

Proposition 8.

; ; ; ; ; when , ; otherwise, .

Proposition 8 indicates that in the case of information asymmetry and the existence of supplier channel infringement, the wholesale price of the supplier, the sales volume through the direct sales channel, and the market clearing price of the retailer will all increase as the level of green input e increases. However, the order quantity of the retailer, that is, the sales volume, is not affected by the level of green input, and the retailer’s profit is negatively correlated with the level of green input. At the same time, the profit of the supplier is nonlinearly affected by the level of green input: when the level of green input is below the threshold, its profit is proportional to the level of green input, and when it is above the threshold (), it is inversely proportional. First, as green input increases, the supplier enhances the environmental attributes and market recognition of the product through the adoption of more advanced environmental protection technologies and green processes, thereby increasing the added value of the product. This enables the supplier to set a higher wholesale price and also enhances the profitability of its own direct sales channel, prompting the supplier to increase the sales volume through direct sales to fully utilize the market advantage brought by the green premium. The market clearing price of the retailer also increases due to the increase in the value of green products, reflecting the increased willingness of consumers to pay a premium for green products and the improved market acceptance. However, the order quantity of the retailer shows strong rigidity in response to changes in the level of green input. The main reason is that the retailer’s purchasing decisions are more dependent on market demand and price elasticity, and the price adjustment brought by green input does not significantly change the purchase quantity of consumers or the inventory strategy of the retailer. At the same time, the retailer’s profit is negatively correlated with the level of green input, mainly because the green input raises the wholesale price of the supplier, increases the procurement cost of the retailer, and compresses its profit margin. The profit of the supplier shows a clear nonlinear characteristic: when the level of green input is below a certain critical threshold, the market recognition and price premium effect brought by green input can cover the input cost, and the supplier’s profit increases accordingly; when the green input exceeds this threshold, the input cost rises rapidly, the marginal cost exceeds the marginal revenue, and the profit decreases. This inverted U-shaped relationship reflects the law of diminishing marginal benefits of green input and cost pressure.

For completeness, we also provide proof sketches for limiting cases (e.g., no green investment e, direct-only encroachment ) in Appendix A, which show that our model reduces to the classic double marginalization and DM-relief versus cannibalization results.

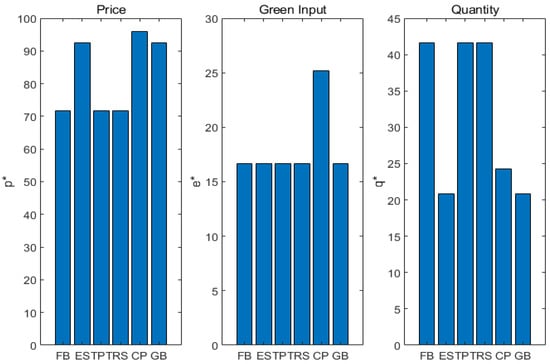

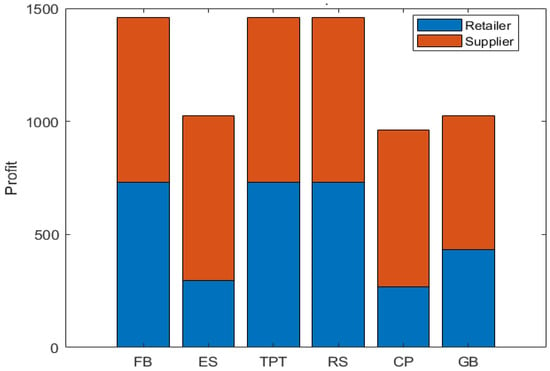

6. Simulation Analysis

In order to analyze the actual impacts of the fairness concern coefficient and the green input level on both suppliers and retailers, this study conducted numerical simulation analysis of four scenarios under information symmetry: no supplier encroachment (SN), supplier encroachment under information symmetry (SE), no supplier encroachment under information asymmetry (AN), and supplier encroachment under information asymmetry (AE) using Matlab 2020a. By adjusting the variable parameters and monitoring the simulation process, the possible optimal stable strategies can be identified. To map the scale of the real market to the model parameters, this paper takes the 2023 online retail sales of physical goods in China at CNY 15.42 trillion as the overall market benchmark (https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202401/17/content_WS65a73b30c6d0868f4e8e32d7.html, accessed on 28 July 2025) and sets v = 10 to reflect the potential value of the mainstream channels. Considering that the live-streaming e-commerce channel accounted for approximately 31.9% of the overall market that year and had an annual growth rate of over 30% (https://www.nextmsc.com/news/live-commerce-how-china-leads-and-the-world-follows, accessed on 28 July 2025), its combined market share and growth premium make its potential about 1.2 times that of the mainstream channels. Therefore, the high-potential sub-market is set as vₕ = 12. Meanwhile, the online retail sales in rural and remote areas only accounted for about 27.6% of the overall market (https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202401/17/content_WS65a73b30c6d0868f4e8e32d7.html, accessed on 28 July 2025), with a corresponding potential of approximately 0.415 times that of the mainstream channels. After mapping, the low-potential sub-market is set as vₗ = 4 to reflect its relatively high maturity and limited penetration rate. While this proportion reflects the overall rural e-commerce market, it may not precisely represent the demand structure for high-priced, low-carbon products, which generally have a smaller penetration in rural markets. Therefore, the parameter setting should be interpreted as an approximation for market potential differences between high-demand and low-demand segments, rather than an exact measure for specific product categories. Future studies could calibrate vₕ and vₗ using product-specific sales data when available. According to the basic assumptions of the model, the parameter values are set as Table 2:

Table 2.

Parameter assignment.

6.1. No Supplier Encroachment Under Information Symmetry (SN)

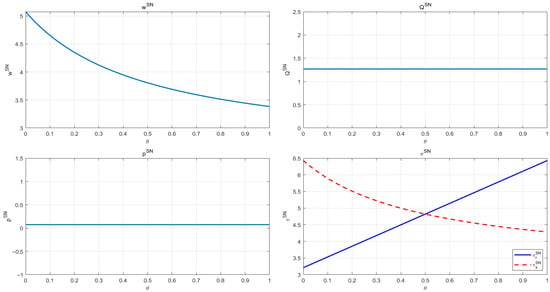

Figure 2 shows that under the condition of information symmetry and no channel invasion by the supplier, as the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient θ increases, the supplier’s optimal wholesale price and profit both show a significant downward trend, and the retailer’s profit increases significantly with the increase in the fairness concern coefficient. At the same time, the retailer’s market clearing price and order quantity remain basically unchanged and are not affected by the change in the fairness concern coefficient. This simulation result is completely consistent with Inference 1.1, verifying its theoretical expectation: in order to maintain the cooperative relationship with the retailer with enhanced fairness concern, the supplier will proactively lower the wholesale price to alleviate the retailer’s fairness demands, thereby leading to a decrease in its own profit, while the retailer benefits from the reduction in procurement costs. This indicates that in the context of information symmetry and no channel invasion by the supplier, the retailer’s fairness concern not only significantly affects the supplier’s pricing and profit distribution behavior but also promotes the reduction in wholesale prices, thereby enhancing the retailer’s own profit level. Meanwhile, the retailer’s market clearing price and order quantity remain stable and are not affected by the change in the fairness concern coefficient. This finding suggests that fairness concern, as a channel behavior norm, can effectively alleviate the double markup problem in the supply chain, enhance the cooperation willingness among channel members, and further improve the coordination and efficiency of the entire supply chain.

Figure 2.

Impact of the fairness concern coefficient on , , and under SN (e = 0.5).

Therefore, it is recommended that suppliers in actual operations should attach importance to and actively respond to the fairness concern demands of downstream retailers by reasonably adjusting the wholesale price to enhance trust and cooperation among channel members and prevent channel conflicts caused by uneven profit distribution. At the same time, supply chain managers can take fairness concern as an important means to improve channel coordination and optimize overall efficiency, thereby achieving a win–win situation and long-term cooperation among supply chain members.

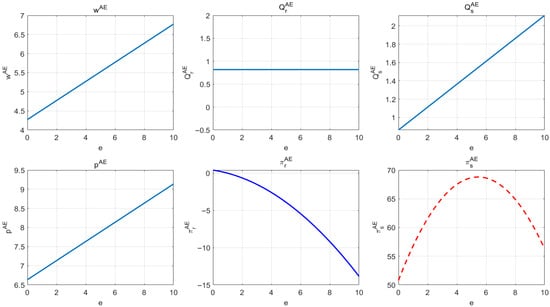

Figure 3 shows that under the condition of information symmetry and no channel invasion by suppliers, the increase in the level of green investment e significantly affects the decision-making behaviors and profit distribution of all members in the supply chain. Specifically, as the level of green investment increases, the optimal wholesale price of the supplier and the order quantity of the retailer both show a monotonically increasing trend, while the market clearing price of the retailer continues to decline. The profits of both the supplier and the retailer exhibit a typical inverted U-shaped change trend: when the level of green investment is low, profits increase with the increase in the level of green investment; when the investment level exceeds a certain critical value, profits gradually decrease. This simulation result is completely consistent with Proposition 2, verifying the nonlinear impact of the level of green investment on the pricing and profit distribution decisions of supply chain members. The formation mechanism lies in the following: On the one hand, moderate green investment enhances the environmental image and market competitiveness of the product, enabling the supplier to increase the wholesale price, and the retailer’s sales volume increases accordingly. On the other hand, excessive green investment leads to a significant increase in costs and diminishing marginal returns, which instead erodes the profits of both parties. This change reflects the law of diminishing marginal benefits of green investment.

Figure 3.

Impact of the green investment level on , , and under SN ( = 0.3).

In conclusion, this research finds that there is an optimal range for the level of green investment for all parties in the supply chain. It is necessary to neither ignore the premium effect brought by green attributes nor be overly cautious about the cost pressure caused by excessive investment. Therefore, it is suggested that suppliers should scientifically grasp the level of green investment in actual decision-making, seek a balance point between investment and returns, and achieve profit maximization. At the same time, retailers should dynamically adjust their pricing strategies based on market demand, jointly promoting the green upgrade and sustainable development of the supply chain.

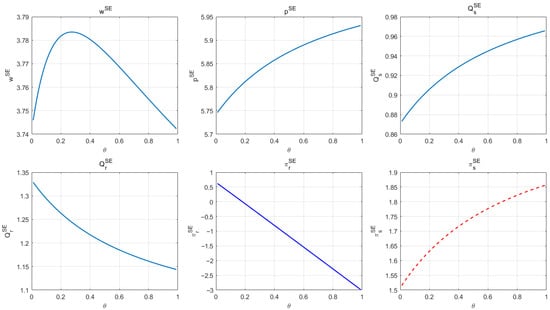

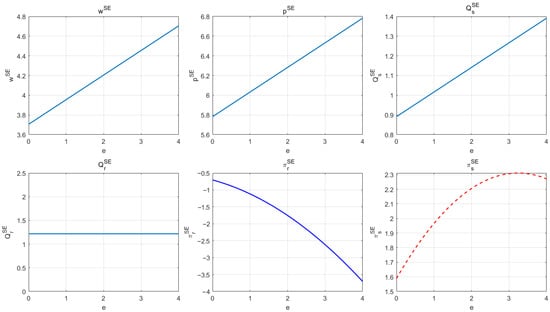

6.2. Supplier Encroachment Under Information Symmetry (SE)

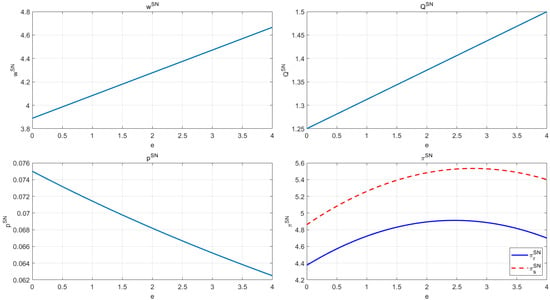

Figure 4 shows that in the case of information symmetry and the existence of supplier channel encroachment, the increase in the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient θ brings complex and nonlinear impacts on the pricing, ordering decisions, and profit distribution of all parties in the supply chain. As the fairness concern coefficient increases, the sales volume of the supplier’s direct sales channel shows a downward trend, and the sales volume of the retailer’s channel also continues to decrease. The changes in the supplier’s wholesale price and profit both exhibit nonlinear characteristics: the wholesale price increases with the increase in the fairness concern coefficient in the low fairness concern range but turns to decrease after exceeding the threshold, and the supplier’s profit shows a similar trend. At the same time, the market clearing price of the retailer increases with the increase in the fairness concern coefficient, while the retailer’s profit only starts to increase with the increase in the fairness concern coefficient after it exceeds the threshold. The above simulation results are completely consistent with Inference 2.1, verifying the mechanism of fairness concern in the dual-channel game. The internal logic is as follows: when the retailer’s fairness concern is weak, the supplier can increase the wholesale price to obtain greater profits. At this time, the channel game is dominated by efficiency maximization, and the retailer’s profit is suppressed. However, as the fairness concern coefficient gradually increases, the retailer’s attention to profit distribution significantly increases. If the supplier continues to increase the wholesale price, it will encounter the retailer’s resistance or purchase reduction, eventually forcing the supplier to lower the wholesale price and benefit the retailer, reversing the profit structure. At the same time, the retailer’s sales volume actively shrinks due to a greater focus on profit distribution, enhancing its bargaining power, and the market clearing price rises accordingly, but the overall sales volume cannot increase simultaneously.

Figure 4.

Impact of the fairness concern coefficient on , , and under SE (e = 0.5).

In conclusion, this research finds that fairness concern in a dual-channel environment triggers complex profit and pricing dynamics, with prominent nonlinear game characteristics. It is suggested that suppliers should pay attention to the fairness demands of downstream retailers when formulating pricing and channel strategies and dynamically adjust the wholesale price and profit distribution methods to prevent channel conflicts and efficiency losses caused by imbalanced profit distribution. Retailers need to rationally evaluate the bargaining power gains and sales volume changes brought about by the increase in fairness concern and find the balance point that maximizes their own interests. Through dynamic coordination and benefit balance, the continuous healthy development of the dual-channel supply chain can be achieved.

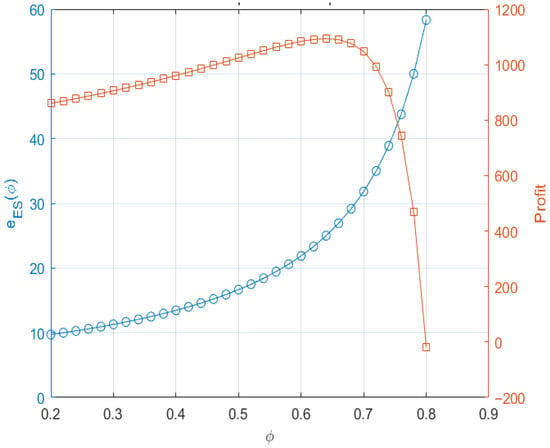

Figure 5 shows that under the condition of information symmetry and the existence of supplier channel invasion, as the level of green investment e increases, the supplier’s optimal wholesale price, direct sales channel sales volume, and the market clearing price of the retailer all show a continuous upward trend. However, the retailer’s order quantity is almost unaffected by the level of green investment and remains stable. In terms of profit, the retailer’s profit continuously decreases as the level of green investment increases, while the supplier’s profit shows a typical inverted U-shaped change: when the level of green investment is below a certain critical threshold, the profit increases with the increase in the investment level, but after exceeding the threshold, it declines due to the rapid increase in investment costs. The above simulation results are consistent with Inference 2.2, fully verifying the complex impact mechanism of the level of green investment on the distribution of benefits in the dual-channel game. Specifically, as the level of green investment increases, the supplier can obtain a market premium through higher environmental attributes, thus increasing the wholesale price and direct sales volume, while the retailer’s terminal selling price also rises simultaneously. However, due to the increasing marginal cost of green investment, the supplier’s profit only benefits within a moderate investment range; once the investment is too high, the cost pressure erodes the profit margin. At the same time, the retailer’s ordering decision is mainly driven by market demand and channel structure. Although the additional value brought by green attributes increases the price, it does not effectively stimulate the expansion in sales volume. Instead, due to the increase in purchase costs, the profit continues to decline.

Figure 5.

Impact of the green investment level on , , and under SE ( = 0.3).

In conclusion, this research finds that the green premium benefits in a dual-channel supply chain are mainly controlled by the supplier, and the retailer is in a passive position during the process of increasing green investment, with its profit space being squeezed. When promoting the transformation of the green supply chain, the supplier should reasonably control the level of green investment to avoid the diminishing marginal returns caused by excessive investment. At the same time, supply chain managers should optimize the distribution mechanism of green premium benefits to enhance the retailer’s enthusiasm for participating in the green transformation, achieving the coordinated development and long-term sustainability of the green supply chain.

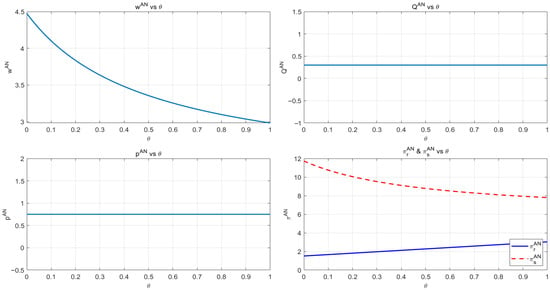

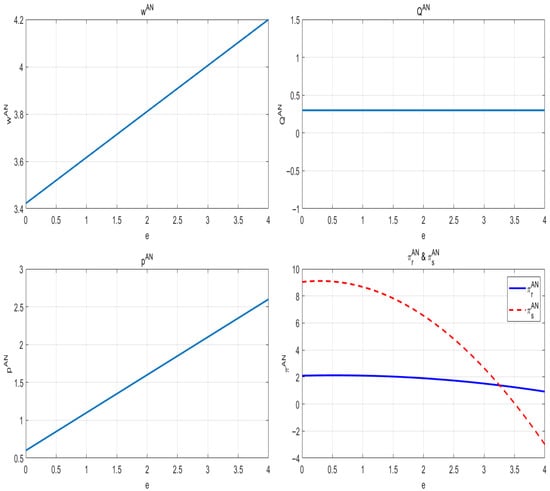

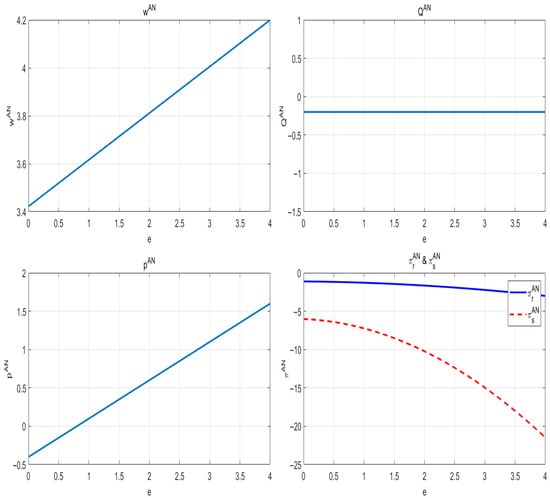

6.3. No Supplier Encroachment Under Information Asymmetry (AN)

Figure 6 shows that in the context of information asymmetry and without channel encroachment by the supplier, as the retailer’s fairness concern coefficient θ increases, the supplier’s wholesale price and profit both exhibit a monotonically decreasing trend; meanwhile, the retailer’s market clearing price and order quantity remain largely unchanged, unaffected by the variation in the fairness concern coefficient. At the same time, the retailer’s profit gradually increases as the fairness concern coefficient rises. These simulation results are consistent with Inference 3.1, verifying the impact mechanism of fairness concern on supply chain pricing and profit distribution under information asymmetry. The underlying logic is that as the retailer’s degree of fairness concern increases, the supplier, to avoid deterioration of the channel relationship and conflicts over profit distribution, voluntarily lowers the wholesale price to respond to the retailer’s demands, sacrificing some of its own profits to maintain the stability of the cooperation. The retailer, due to the reduction in procurement costs, gains a larger profit margin, but its pricing and order quantity are still mainly determined by market demand and price elasticity and do not change significantly due to the fairness concern factor.

Figure 6.

Impact of the fairness concern coefficient on , , and under AN (e = 0.5).

Under information asymmetry, the retailer’s enhancement in fairness concern helps to strengthen its bargaining power, prompting the supplier to adjust the wholesale price to maintain channel cooperation, but it also forces the supplier to make a trade-off between profit transfer and the channel relationship. In reality, suppliers should closely monitor changes in the retailer’s fairness concern, proactively optimize the profit distribution mechanism, and enhance the stability of channel cooperation. Retailers, on the other hand, can strengthen their bargaining power by reasonably expressing fairness concern, obtain more favorable cooperation conditions, and promote the long-term healthy development of the entire supply chain.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate the impact of the level of green investment on the key decision variables of supply chain members in the context of information asymmetry. Figure 7 shows the situation where the retailer’s expected market demand is higher than that of the supplier, while in Figure 8, the retailer’s expected market demand is lower than that of the supplier.

Figure 7.

Impact of the green investment level on , , and under AN ( = 0.3, ).

Figure 8.

Impact of the green investment level on , , and under SN ( = 0.3, ).