Abstract

This study examines the challenges and opportunities of managing electronic waste (e-waste) in the Galapagos Islands, a globally significant yet vulnerable subnational insular jurisdiction (SNIJ). Drawing on theories of Circular Economy (CE) and Political Industrial Ecology (PIE), the research investigates the status of e-waste in the archipelago, the barriers to implementing CE practices, and the institutional dynamics shaping material flows. Using a mixed-methods approach—including archival analysis, participant observation, and semi-structured interviews with key informants from government, private, and nonprofit sectors—the findings presented here demonstrate that e-waste management is hindered by limited capital, infrastructure, public awareness, and fragmented governance. While some high-capital institutions can export e-waste to mainland Ecuador, most residents and low-capital entities lack viable disposal options, leading to accumulation and improper disposal. The PIE analysis yielded findings that highlight how institutional power and financial capacity dictate the sustainability of e-waste pathways, with CE loops remaining largely incomplete. Despite national policy support for CE, implementation in Galapagos remains aspirational without targeted financial and logistical support. This case contributes to broader discussions on waste governance in island settings and underscores the need for integrated, equity-focused strategies to address e-waste in small island developing states (SIDS) and SNIJs globally.

1. Introduction

Waste management in island settings is incredibly challenging due to limited space, isolation, lack of capital and infrastructure, extreme weather, and small market sizes [1,2,3]. Presence of endemic species and ecosystems are often particularly sensitive to human disturbances including but not limited to waste accumulation [4]. Consequently, waste management in island settings involves diverse “institutional, financial, technical and educational” arrangements, and problems that arise often require the involvement of numerous societal sectors [3] (p. 546). It is thus often complicated by polycentric governance issues, including gaps in responsibility from institutions, policy adaptability, and local political jockeying [5]. With exponential growth in island tourism in recent decades [6], responsible institutions have struggled to keep pace with growing management needs, often resulting in stagnation of material flows of waste [3,5,7,8]. This waste accumulation produces further human and environmental health concerns, as well as degradation of visual aesthetic quality for tourists and residents [2,7]. Growing human population (both visitors and residents) on islands will drive even greater concern for waste management and governance in the coming years.

One material that, if left stagnant, can have particularly dangerous socioecological consequences is electronic waste, or e-waste. Within the scholarly literature, the term ‘e-waste,’ commonly interchanged or substituted with ‘waste electrical and electronic equipment’ (WEEE), refers to ‘electrical and electronic equipment’ (EEE) that has reached its end of life (EoL) either by necessity or by choice, and has moved to the waste stream [9,10]. Examples of e-waste can include, but are not limited to, electro-domestic household devices (e.g., microwaves, blenders, refrigerators), medical devices, electric vehicles (e.g., bikes and cars), desktop and portable computers, batteries, and cell phones. The documented growth of e-waste is occurring at a rapid pace [10,11,12] and is estimated to grow to 74 Mt globally by 2030 [13] as more EEE products enter the market and the middle class grows [10,14]. As WEEE accumulates, so do the consequences for humans. E-waste can contaminate nearby water, soil, air, and crops [15,16,17,18] and contribute to severe health problems, such as decreased thyroid and cellular function, as well as birth defects [19,20].

According to UNEP [8], e-waste, listed under hazardous waste, is considered a top priority for small island developing states, or SIDS. The relative deficiency of institutional resources in developing countries creates even greater e-waste management challenges in those settings, including but not limited to lack of infrastructure and e-waste-specific legislation [21,22]. E-waste recycling facilities typically require a high level of startup funds and advanced technology that are often unobtainable, particularly when collection and management systems are already deficient [18,21]. Subnational island jurisdictions (SNIJs) in lesser developed countries frequently represent the periphery of state-level infrastructure [23] and thus face even greater challenges in managing e-waste on developing islands experiencing growing tourism visitation [4,6].

Nowhere is it more critical to understand the management of waste (and e-waste) than in the world’s most treasured natural area and its first UNESCO World Heritage Site—the Galapagos Islands. Despite having no native human population and total population that remained under 1500 people as of 1950, scholars have estimated that the official population numbers of 28,583 permanent residents is actually closer to 35,000 when including estimates of the informal population sector [24,25]. Furthermore, the Galapagos experienced close to 330,000 tourist arrivals in 2023 [26] and 280,000 in 2024 [27], both higher than previous years, leading to growing concerns about overtourism [28] and the first changes to the visitor fee since 1998 [29]. The growing human presence in the islands threatens fragile endemic species, introduces invasive species that threaten them, and disrupts their habitats. Yet, tourism also brings critical resources to the Galapagos National Park and local provincial and municipal governments, and the expectation is that tourism will continue to grow, as will the local population, the majority of whose livelihoods are directly linked to tourism [30]. Despite lack of data on volumes of e-waste accumulation on the islands, there is documentation that Ecuador produced 99,000 metric tons of WEEE in 2022 [31], and in the same year 14 tons of e-waste were collected and shipped off island in Santa Cruz [32]. Ecuador has seen a steady rise in e-waste production since 2015 [31,33]. As local and tourist populations have increased in Galapagos, we can only assume that so too has the volume of WEEE increased, reflecting mainland Ecuador’s trajectory.

The purpose of this study is to understand waste management issues in the Galapagos Islands. Given the disproportionate health impacts of e-waste and lack of relevant data in the islands, we focus on the management of e-waste in the archipelago. The first objective is to answer a key descriptive question: (1) What is the current status of e-waste in Galapagos, and how did it evolve into its current configuration? Then, drawing on circular economy (CE) and political industrial ecology (PIE) theories, we seek answers to the following more theoretically driven questions: (2) What are the current challenges to adopting a CE approach to e-waste management, and drawing upon lessons from other contexts, what opportunities exist—if any—to overcome these challenges to an e-waste CE involving Galapagos? and (3) How are institutions—municipal, provincial and national—and the associated political processes among them differentially enabling or inhibiting the material flows and accumulation of e-waste in Galapagos?

To answer these questions, this study draws upon years of experience with various ethnographic and field-based research projects in Galapagos among the author team, extensive participant observation associated with this prior work, thorough archival document analysis related to waste management in the islands, and semi-structured key informant interviews with purposively selected key informants most knowledgeable about waste management practices in Galapagos. This combination of interview, participant observation, and archival data analysis permit triangulation of the findings and conclusions drawn from them. While this work focused on one specific setting, it will be of interest to scholars and practitioners interested in solutions to growing waste management challenges in other SIDs and SNIJs settings around the globe.

Theoretical Framing

Stemming from the sustainable development paradigm focused on combatting human-driven environmental degradation associated with the Anthropocene [34], the theory of a circular economy (CE) emerged in the 1990s in China as a response to economic growth and natural resource limitations [35,36]. Echoing ideas originated as early as the 1940s and 1950s about linking industry inputs and outputs and responding to Limits to Growth concerns [37], CE principles focus on maintaining cycles or loops of material or resource flows (e.g., of energy or water) in systems entirely within the planetary boundaries, with no need for further extraction [36,38,39,40]. CE incorporates solutions drawn from the discipline of industrial ecology (IE), which makes an explicit effort to describe industrial systems in the terms used to describe living, biological systems [39,41]. As such, CE scholars differentially explore “policy instruments and approaches; value chains, material flows, and products; and technology, organizational, and social innovation” as various means of creating closed-loop CE systems [35] (p. 825).

With the blossoming of CE and IE literature in recent decades criticism has followed. Critics emphasize that these concepts rarely incorporate a system’s social components in a meaningful way [38,42,43,44]. As Pickren [45] highlights, “to date, studies of e-waste have been dominated by the fields of waste management, engineering, chemistry, and public policy” (p. 111). In an effort to place greater emphasis on critical social aspects of CE and IE, political industrial ecology (PIE) emerged. PIE endeavors to shed light on issues of equity, power, justice, and governance in a given system [46,47]. PIE thus merges an awareness of local politics, ethics, and power dynamics with the traditional logistical and design emphasized in IE scholarship to better account for the relationships between resource flows and “environmental, socio-economic, and political processes” [47] (p. 319). Therefore, PIE enables more holistic analyses of socioecological systems around waste management issues. As seen in Table 1, a review of the goals, strategies, and associated concepts of CE and PIE offers a comparison of the two theoretical frameworks. E-waste is an essential material flow given the highly limited nature of the raw mineral resources needed to develop the original electronic materials. Limiting the need for further extraction of raw metals and also minimizing waste piles that contribute to human and environmental health issues are both strong rationales for greater application of CE principles to e-waste management [48].

Table 1.

Comparative table of relevant theoretical frameworks.

While there has been relatively little integration of CE scholarship into the PIE literature, and vice versa, there is some overlap in the ways that both bodies of scholarship engage with the concept of institutions (Table 1; e.g., [42,43,44,49]). Institutions are “economic and industrial systems that entail multidimensional configurations of economic and political agencies,” and usually have significant power in dictating whether or not CE or other waste management models will be successfully adopted [42] (p. 152). Schulz et al. [44] argue that institutions “determine social practices and affect regulation and policymaking” in a CE system (p. 4). Scholarship to date further suggests that it is in local institutions where the power resides to influence policies, cost distributions, and movement towards or away from a CE model [43,44,49,50]. Integrating an institutional focus into a PIE analysis can thus identify which individuals or institutions hold power and the associated social and economic significance needed to implement (e-)waste management solutions.

Waste, including WEEE, is a growing issue as consumption continues to skyrocket globally [14]. In addition to more mindful and responsible consumption (near the beginning of the EEE lifecycle), islands in particular are in need of stronger institutional responsibility surrounding waste management (the end of the EEE lifecycle) [3,4,5,23]. Governance of e-waste management systems can be difficult on islands as many are governed by a national government on a remote mainland [51]. Further challenges to e-waste management in these settings exist due to “lack of available land and financing resources, vulnerability to extreme weather events, higher operational expenditures, small internal markets, and changing community norms” [12] (p. 2), in addition to lack of local awareness surrounding problems and consequences of unmanaged e-waste [7,12]. Collection and transportation costs are also often disproportionally higher on islands due to their isolation and decentralized populations, making it most common for islands to export their waste [52]. Yet even when options to export more mainstream waste exist, many islands still see accumulation of e-waste due to the lack of means for proper disposal or export [52]. This lack of proper management directly impacts biodiversity, community recreational opportunities, and aesthetics for tourist visitors and residents [12,18,23].

In keeping with a PIE approach to CE, better understanding of e-waste management responsibilities in island settings requires categorizing the formal (and informal) institutions that dictate the “rules” of e-waste management, as evidence through regulations and policies implemented locally [5]. With institutional arrangements resulting from the relationships among powerful stakeholders dictating the structure of waste governance, it is prudent that institutions be included in discussions pertaining to applications of CE to e-waste. Despite the clear relevance of the perspectives to e-waste management on islands, they have not been theoretically integrated nor empirically explored in island settings facing e-waste management challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

The Galapagos Islands, named a National Park in 1959 and the first UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978, consist of 19 islands in the Pacific Ocean governed by Ecuador. While 97% of the terrestrial area of this archipelago is within the National Park boundaries, humans use is permitted in the remaining 3%. Four islands have population centers: Santa Cruz (approximately 20,000 residents), San Cristobal (approximately 9000 residents), Isabela (approximately 4000 residents), and Floreana (approximately 300 residents). The islands are a province of Ecuador yet governed by a unique Special Organic Law (LOREG) established in 1998 that created a biosecurity agency to control the influx of invasive species as well as a governing council for Galapagos (CGREG), separates immigration and residency status, manages cruise-boat berths, determines national park entrance fees, and provides other policy devices designed to protect the islands’ globally significant endemic biodiversity. The president of CGREG serves at the pleasure of the president of Ecuador, as do the national environmental ministry that oversees the National Park and those in the national ministry of Tourism. These non-elected positions are characterized by high turnover. For instance, between 2019 and 2025, no less than five individuals have served as president of CGREG, while the Galapagos National Park has had at least nine directors between 2012 and 2025. Meanwhile, local mayors and municipal government leadership are elected. This polycentric governance milieu in the islands complicates long-term planning for sustainability in the islands. Case in point, the Galapagos has yet to establish and implement an e-waste usage and management plan. Through advisement from the Charles Darwin Foundation, who identified e-waste as a high importance issue, this study was developed.

2.2. Data Collection

Primary data collection techniques consisted of archival retrieval, semi-structured key informant interviews, and participant observation over multiple field seasons in Galapagos [53]. Archival documentation related to waste management planning was collected before, during, and after in situ fieldwork for this project. This documentation was sourced from key governmental informants as well as public documents available on the Ministry of the Environment and other Ecuadorian governmental institutions’ websites. To obtain the online public documents, several search terms were utilized, including combinations of circular economy, WEEE, waste, electronics, Santa Cruz, Galapagos (searched in the Spanish translation). The relevant documents were deductively analyzed in MAXQDA 12 to find additional information pertaining to institutions, waste and e-waste management, and circular economy.

Semi-structured key informant interview participants were purposively selected with the criteria that they hold a role in EEE management within their represented institution [54,55]. Table 2 demonstrates the number of key informants and their institutional representation. Governmental institutions represented by the interviewed individuals include the Ministry of Agriculture, Galapagos National Park, and Municipal Government. Private refurbishing and collecting businesses operating locally were also represented. Lastly, the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), the oldest institution in the archipelago, together with the Galapagos National Park, is represented in the interviews. Furthermore, the CDF aided in driving this study with the intention of gazing inward to become better stewards of (e-)waste management within their own operations and thus serve as an inspiration for other institutions in the islands. Interview participants could only be part of this study if their institution formally responded to a letter distributed by the CDF. Institutions were selected by the CDF, more of which were contacted during this study but did not formally respond. Private businesses were selected through snowball method, where interviewees identified the private businesses that their institutions work with for collection and refurbishing.

Table 2.

Institutions represented by the key informants in this study.

In June and July 2023, all semi-structured interviews were conducted in Spanish on Santa Cruz Island after verbal consent was provided in accordance with the Institutional Review Board overseeing the Ethical Conduct of this Research (see Statement at the end of this paper). Each interview began with a conversation on what qualifies as WEEE to ensure all participants shared understanding of terminology incorporated into the subsequent questions. The interview then proceeded with a “grand tour” question regarding the existence and current management of e-waste in Galapagos [56]. Interview questions then focused in on descriptions of the following topics: specific types of e-waste that institutions producing; existence of or need for an e-waste management plan; who should be responsible for such a plan; what limitations exist in creating a management plan; and level of comparative concern for e-waste in Galapagos.

2.3. Data Analysis

Archival, participant observation, and semi-structured interview data were imported into a corpus of text in MAXQDA 12. In that software environment, structural and thematic coding of this body of text was conducted [57]. Due to the semi-structured nature of these interviews, interview question order was not always consistent as the interviewer occasionally pivoted to other questions in the interview guide in response to content provided by the interviewee. Therefore, to assist with retrieval of relevant information, the first coding pass focused on structural coding based on the structure of the interview guide and associated question. From there, thematic analysis of the entire corpus of text (i.e., archival, participant observation, and interview data) proceeded on the basis of both deductive coding of content of theoretical interest (e.g., material flows of EEE) as well as exploratory inductive coding of additional themes that emerged due to patterns and repetitions in interviewee responses, metaphors, comparisons, emic categorizations, expressed similarities and differences, and linguistic connectors employed by the key informants [57,58]. When possible in vivo codes were developed to reflect informants’ emic views and language. Focused coding was used to identify and categorize data, and pattern coding was used to find possible “rules” or explanations within these categories and processes associated with the management of e-waste in the islands [58].

3. Findings

3.1. Current State of E-Waste in Galapagos

Key informants indicate that users have multiple pathways for purchasing electronics, including on-island internal vendors, purchases of smaller electronics made outside of the islands and then transported on one’s person to the islands, or off-island purchases of larger electronics and appliances through external vendors that then arrange for cargo transport to the islands. Once electronics are inside of the island boundary and are determined to be ready to discard, different disposal avenues again exist. If the user is a small private company or individual household, then options for disposal include bringing the e-waste to the Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado Municipal de Santa Cruz (municipality of Santa Cruz, the most populous island in the archipelago) or putting items in the recycling or garbage bins for collection. Items that are accepted by the municipality are later collected by a private Galapagueño company that ships the materials to mainland Ecuador.

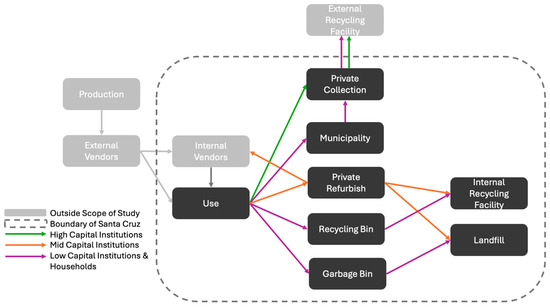

However, the municipality will not take any e-waste that is not completely intact nor considered hazardous. Because most e-waste consists of hazardous materials, the key informants indicated that the most utilized option for residents is to dispose of smaller e-waste items in garbage or recycling bins. They also cited little public awareness of information regarding landfill and recycling facility management, leaving timeframes and procedures for shipping e-waste materials off island largely unknown, even among the majority of the key informants interviewed here. For larger items, informants identified several private companies that collect e-waste in Santa Cruz, often in the interest of refurbishing and reselling it. Other companies simply ship it off island and back to mainland Ecuador. If the user is an institution, then the e-waste is counted in inventory and awaits private collection. Figure 1 demonstrates these current flows of electronic materials in Santa Cruz Island. The dotted line represents the boundary of the island.

Figure 1.

Conceptual map of the material flow of e-waste in Santa Cruz, Galapagos.

3.2. Challenges to the Adoption of a CE Approach to E-Waste Management

Key informants proceeded to identify four main challenges or limitations to e-waste management in Galapagos. Not surprisingly, the challenges identified overlap considerably with the four broader challenges the nation of Ecuador faces in waste management, as indicated in our archival data analysis: (1) lack of capital, (2) lack of infrastructure, (3) limited public awareness, and (4) ineffective policies [59]. Elaborating first on lack of capital, key informants identified cost as the most prominent e-waste management challenge in Galapagos. While a few well-funded governmental and non-governmental institutions have the capital to pay for private companies that ship materials off island, this process is often prohibitively expensive for smaller businesses and individuals. This type of e-waste recycling effort is costly as materials must be collected, shipped, and then transported to a major city, such as Guayaquil or Quito on mainland Ecuador. Rather than ship items to the mainland, lesser-funded institutions rely on private companies to refurbish materials locally as this option is more affordable and still something that key informants characterized as an effort to be more sustainable. For individuals and households without financial means to pay a private e-waste collection company, their options are limited to dropping off their discarded materials at the municipal office, putting e-waste out for curbside recycling or garbage collection, or simply allowing materials to accumulate in or around their households.

Key informants also identified lack of infrastructure and public awareness as challenges for more sustainable e-waste management in Galapagos. One private business representative noted, “I think that there should be infrastructure, because…within Ecuador, Galapagos is the best in garbage management [and] recycling.” This comment reflects that of many key informants that Galapagos, as a globally significant national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site, should be setting the standard for sustainable practices in Ecuador, including its standards for waste management. Nevertheless, there is a consensus view among key informants that the islands’ currently lack infrastructure for e-waste management and that its capacity for traditional waste and recycling is likewise challenged. However, the landfill and recycling center on Santa Cruz islands are removed from public view, thereby limiting broader public awareness of the growing problem of waste management. As an interviewee from a governmental institution explained, “If people saw the trash and impact, they would change.” Echoing the concerns of other informants, this individual believes that until the magnitude of waste generated on Santa Cruz is made more visible to the public, including e-waste accumulating in particular locations, there will be little political will to adjust the practices of residents, businesses and institutions in Galapagos.

As noted, these challenges are not unique to the province of Galapagos. Ecuadorian government policy documents (e.g., [59,60]) make frequent reference to circular economy practices, including in relation to waste management. There has additionally been an assessment of CE adoption in mainland Ecuador [33]. According to such documentation, strategies for CE should include education, awareness raising, and “responsible consumption to promote reuse, reuse, repair, remanufacturing, and recycling” [59]. Stronger regulations and infrastructure are also encouraged [33]. There is thus recognition amongst the national government and academics of a need to overcome limitations to managing waste, including its collection, separation, disposal, and the infrastructure and technology needed to achieve circular economy practices [59]. However, e-waste is not directly addressed within existing national CE guides or other waste management documentation.

Where e-waste does appear in relation to CE is in blog postings published by the Ministerio de Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica (Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition), or MAATE. A blogpost relaying the WEEE collection activities in Galagos in 2022 [32] states that the e-waste collected will be “reincorporated into the production processes, thus promoting the country’s circular economy.” A different post in 2022 discussing e-waste recycling for the whole of Ecuador provides the following quote: “’Recycling and giving new life to this waste is an action I have promoted for several years, and this, in turn, has allowed me to be part of the circular economy chain that has benefited many families in the province of El Oro”’ [61]. Archival government documents and other online blog data demonstrate that MAATE has collected and dismantled tons of e-waste into raw materials to be repurposed and reproduced, thereby achieving key objectives of CE management. Yet archival analysis and key informant data make it clear that, despite limited evidence of successful CE practices in mainland Ecuador [33], to date no provincial plans or guides have manifested on e-waste management that connect the province of Galapagos to ongoing CE materials loops on the mainland.

3.3. Institutional Arrangements Related to E-Waste Management

A few isolated initiatives serve as exceptions to the lack of focus on e-waste collection needs in Galapagos. In 2013, the municipality of Santa Cruz conducted a large collection of e-waste and shipped it off-island for disposal [62]. To carry out this initiative, the local municipal government partnered with the Galapagos National Park Directorate as well as the World Wildlife Fund, or WWF [62]. Again in 2022, a MAATE collection led to the shipment of e-waste, along with other hazardous wastes, which was enabled with support from the United Nations Development Programme, or UNDP [32]. As the previous time, this MAATE initiative was described as being the first of many hazardous waste transfers from Galapagos to mainland Ecuador. Nevertheless, no further e-waste shipments have been documented by MAATE since.

Key informants identified the lack of action by MAATE as concerning since they identified it as the national governmental entity responsible for all regulations and policy related to waste and recyclables [59]. In the Galapagos, the municipalities must adhere to waste and recycling regulations administered by MAATE from mainland Ecuador, including the provision of e-waste drop-offs. Still, key informants see MAATE’s responsibility as being both financial and logistical. Their responses highlight the much smaller operational budget of municipal governments in relation to large corporate companies, national public institutions, and even the CGREG provincial governing council. Key informants viewed collaborative planning between national, provincial, and municipal institutions, including “regulations with certificates,” as the only means of implementing more effective and sustainable CE approaches to e-waste management. Informants also identified large manufacturing EEE companies as playing a key role in the financing of e-waste management. Additional financial responsibility is seen with the CGREG provincial government, perhaps as allocation of visitor fees. At least a couple of informants also mentioned that residents share some responsibility in paying for any collection service for e-waste as residents bring in much of the electronic materials themselves. Whereas there is high consensus of the need for improved waste and e-waste management among key informants, there is less consensus regarding the logistics, financing, and implementation of more sustainable CE approaches to e-waste management.

3.4. Current and Future Planning

E-waste is labeled as a hazardous, special category of waste in Ecuador. Although e-waste is not specifically mentioned in regulatory archival documents, there are directions from MAATE on how to handle hazardous and/or special waste that dictate the practices that municipalities in Galapagos follow. General policies regarding e-waste are “for both State institutions, at their various levels of government, as well as for public or private, community or mixed, national or foreign individuals or legal entities” [63] (p. 16). Therefore, all institutions have a legal responsibility to properly manage e-waste, and utilize tools such as minimizing waste generation, reusing, and recycling [63]. Final disposal of hazardous and/or special waste can be in a landfill as long as it has the proper governmental permits.

Key informants had multiple ideas on how to solve the e-waste problem in Galapagos. For instance, one individual believes that the protocol of dropping WEEE off at the municipality should be eliminated. Instead, they recommend there be household collection once a week. Other informants believe more public education is vital to improved e-waste management plans. Still, other informant comments drew attention to a need to regulate and potentially limit the importation of EEE to the islands to long lifespan products only, though how such categorization would be determined was not clear. Most informants emphasized the reuse of materials, with one indication from a private business representative that, “here, most of us get a spare part, so the answer would be to reuse.” Reuse and repurposing materials is clearly already practiced in Santa Cruz, more out of necessity than out of any ideological alignment with CE philosophies. Still another private business representative suggested the use of cargo planes to ship e-waste to the mainland, sharing the view that cargo planes would ultimately be “more efficient and less expensive” in the long run than using boats, as is the current practice. Again, while many ideas exist, little consensus exists regarding the best paths forward for improved e-waste management and most ideas remain highly theoretical and beyond current logistical and financial means present among the insular municipal and provincial institutions.

4. Discussion

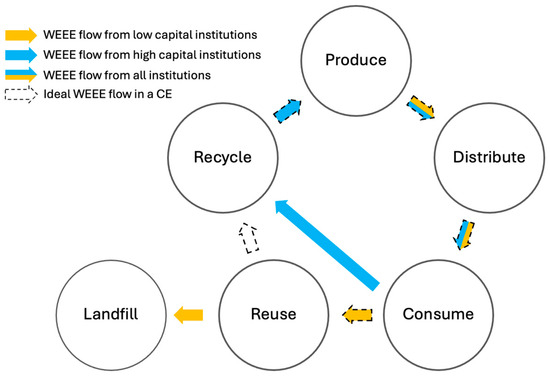

The analysis of data gathered from the subnational insular Galapagos jurisdiction puts the financial and logistical challenges of e-waste management in island settings into sharp relief [4]. Echoing the literature reviewed earlier, Figure 2 illustrates an ideal flow (dotted arrows) that corresponds with ideal CE practices, where after consumption, materials are reused before being recycled. Figure 2 then illustrates more specifically where CE loops in Santa Cruz exist (blue arrows) as well as where they are broken (orange arrows) depending on institutional captial. To achieve circularity, e-waste items must be brought closer to their original production sites by being shipped back to mainland Ecuador. With certain private institutions (e.g., businesses) and NGOs (e.g., the CDF) self-financing such shipments, for the bulk of the population in the islands, the insular island institutions at either the municipal or provincial level must often shoulder the burden of shipping gathered e-waste back to mainland Ecuador. When these institutions have had financial partners (e.g., WWF, UNDP), shipments have been possible. Otherwise, little active e-waste management occurs. While out of broader public view, accumulation of e-waste is evident in particular areas of the islands, such as the recycling center and the “artisanal park,” a largely industrial site where much appliance, boat, and vehicle repair occur. Thus, as noted in other island settings [4,7], the “sustainability” of e-waste management in Galapagos, at the moment at least, depends on external financial support.

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating an ideal circular economy flow of WEEE (dotted arrows), the flow of WEEE produced by low capital institutions on Santa Cruz Island (green arrows), and the flow of WEEE produced by high capital institutions on Santa Cruz (orange arrows).

The data also reflect how SNIJs and SIDs face challenges in maintaining closed, CE loops in relation to waste and e-waste management [7,64]. In the present study, informants representing many of the key institutions were rarely familiar with the destination of e-waste sent to the mainland. Furthermore, when institutions were successful in shipping e-waste items back to the mainland once they were no longer useful, this further demonstrated the lack of opportunities for value-added refurbishment in the islands (e.g., blue arrows in Figure 2). In any case, at the present, selling items to refurbishing companies that promote the practice of refurbishing and reusing is not realistic nor truly circular until items arrive on the mainland. As a result, the majority of leftover e-waste materials that cannot be refurbished locally on the islands are then sent to the landfill. Our archival documentation, key informant interviews, and participant observation of waste management practices in Galapagos indicate that regardless of the e-waste disposal scenario chosen by businesses and local institutions, true CE loops are not currently complete. Even though connections do occasionally exist between particular elements, current regulations, public awareness, availability of financial support, and logistical capacities more consistently inhibit linkages between these elements and thus the closing of CE loops [4]. This places e-waste in island settings in a similar category with construction and demolition waste [65].

Furthermore, from a PIE framework, the flow of e-waste in Santa Cruz reflects the ways in which institutional power influences material flows (linear vs. circular) on islands [5]. As Pickren [45] reinforces, “e-waste and e-waste landscapes…[are] always shaped by asymmetrical relationships of power” (p. 119). In this setting, power is embodied by access to sufficient capital to self-finance e-waste management. The more capital an institution has, the more “sustainable” it can appear to be. Regarding stated MAATE CE goals of eliminating e-waste from the archipelago and bringing it to recycling facilities on the mainland, few institutions have the financial means to do so. Institutions with mid-level capital have the option to pay for a private refurbishing company to take the materials away but cannot pay for the materials to be shipped off island. Institutions with low capital, individuals, and households have the least sustainable pathways. They can bring items to the municipality, but only if the items are nonhazardous and completely intact. Otherwise, low capital entities must keep their items or discard them improperly in the garbage or recycling bins. Mohammadi et al. [12] demonstrate the importance of public awareness and participation to achieve a successful CE of e-waste. However, in the case of Galapagos, even if awareness and willingness to participate existed, there would be limited options to properly discard WEEE. Regional and national governments play a vital role in financing and implementing e-waste management on islands [3,7,12]. Nevertheless, overarching governmental institutions on mainland Ecuador with access to capital do not provide sufficient financial, infrastructural, or logistical aid to on-island waste management institutions.

As aforementioned, institutional power (or lack thereof) helps shape whether or not waste management models (like CE) will be effective [42,49]. By adopting a PIE approach, it becomes clear that power via capital within institutions dictates WEEE material flow in Galapagos [42,47]. This study (e.g., Figure 2) aids in filling the gap regarding the integration of CE scholarship into PIE literature [7,55]. The ideal e-waste CE loop is currently not achieved in Galapagos, despite CE integration into Ecuadorian policy, due to disproportionate institutional capital. To implement a successful WEEE CE loop, institutions with high capital would need to adopt ‘reuse’ practices before collecting their e-waste for shipment. Lower capital institutions would require additional financial and logistical support in order to ship their waste to the mainland after refurbishing and reusing materials [64].

Kalmykova et al. [39] suggest utilizing material flow analysis (MFA) to monitor CE implementation. MFA is defined as “a systematic assessment of the material flows and stocks, based on the mass balance principle, within space and time boundaries” [12] (p. 3). Islands offer prime conditions to apply techniques like MFA [7]. Because this exploratory and qualitative social science research focuses on institutions and power, components of PIE rather than IE, the quantification of stocks and physical flows materials were not a specific focus. Future research could more rigorously employ the techniques of material flow analysis to more clearly quantify the magnitude of EEE arriving to Galapagos as well as the WEEE being produced in the islands. Nevertheless, through this purely qualitative PIE lens, it is evident why EEE materials are flowing or stalling in Galapagos based on institutional power and capital as well as the inherent inequities of e-waste management given that individuals and institutions with disproportionately fewer resources have less or no options to ship their waste off island.

As seen in other island settings [5,66,67], national governmental entities operating in Galapagos (e.g., MAATE) provide policies and regulations that indicate what needs to be done regarding e-waste in a CE, but do not clarify how local-level institutions are to enact these policies nor do they provide adequate financial and logistical resources to do so [42,68]. The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Handbook highlights that in the development of an e-waste management scheme, implementation must coincide with enforcement, infrastructure, and stakeholder cooperation [10]. The Ecuadorian policies indicate how e-waste ought to be managed for the mainland, not for the SNIJ of Galapagos where conditions are different [23]. Further complicating more sustainable CE approaches to e-waste management in Galapagos is the lack of public awareness of existing policies and the existing problem as well as the geographic isolation. As seen in other island contexts (e.g., [51]), lack of public awareness has aided in poorly managing waste (including WEEE) in SIDS. Scholars such as Mohammadi et al. [12] and Gollakota et al. [11] emphasize that raising public awareness of the problem at hand is necessary for behavioral change regarding e-waste. Geographic isolation has likewise been seen to inhibit the closing of CE loops in other SIDs and/or SNIJs [12].

Despite these limitations to achieving greater CE outcomes, our analysis revealed improving management of e-waste over time in Galapagos. For instance, in 2010, a summary of waste management indicated that there was still no separation, collection, or treatment of e-waste [69]. Yet by 2014, there was a street-side collection location for bulky and special waste, including e-waste, which was separated, packaged, and sent to mainland Ecuador [70]. In contrast with this historical documentation, no such option was mentioned by the key informants interviewed in this study. More recently, as previously mentioned, there have been large collection and shipment events in Santa Cruz in 2013 and again in 2022 [32,62]. As other scholars point out (e.g., [7,21,52]), setting up improved e-waste management requires extensive capital investment [12], as was the case in Galapagos when external institutions with more capital (i.e., WWF and UNDP) supported specific e-waste recycling campaigns. This analysis focused on the most populous island, Santa Cruz. Other Galapagos islands are likely to face even greater challenges of economies of scale, public awareness, shipment costs, etc. To the extent that additional capital from external institutions is available, lessons learned on Santa Cruz can inform future collection, separation, and shipment on all populated islands in the archipelago. Yet the question of how to sustainably finance such activities remains unanswered. Greater sharing of best practices among scholars working in diverse SID and SNIJ settings could help reveal existing answers to such questions in the future.

All stakeholders interviewed believe that e-waste is an issue that needs to be addressed in Galapagos. According to key informants, there needs to be some kind of household collection service or a more inclusive drop-off option. Some individuals indicated they were willing to pay for the service if the government will not. To incorporate CE practices, if WEEE is collected, it should be first given to refurbishing companies so that materials can be reused. When the material can no longer be reused, it should be recycled on mainland Ecuador. There are several organizations recycling WEEE on the mainland [68,71], which could create collaborations with Galapagueño institutions in the future. It is worth noting that despite documented recycling facilities in mainland Ecuador, other authors [33] argue that Ecuador does not yet have the legislation or infrastructure needed to adequately recycle e-waste. Further conversations between recycling managers and governments are vital to tackling the problem of e-waste [10,72].

Again, this exploratory and qualitative analysis represents a valuable first step in understanding the opportunities for more sustainable and circular waste and e-waste management in Galapagos specifically, as well as in other SIDS and SNIJs. By using a PIE lens, it is clear that institutions with more capital in Santa Cruz have more opportunities to make a material loop, whereas those with mid to low capital are more restricted. Yet, each institutional category seems to have pros and cons. Despite getting WEEE closer to its production site, high capital institutions do not reuse materials first, which can lead to more consumption of new products. On the other hand, mid and low institutions, as well as individual households, are more likely to initiate reuse practices, but disposed materials will stay on the island.

Future research could build on these findings to develop a broader survey of individuals and institutions in this and other settings to confirm the challenges identified and seek viability tests of the strategies proposed for improving e-waste management in the future [73]. Additionally, given the absence of emic reference to state-of-the-art electronic waste processing technologies (e.g., hydro-metallurgy, pyrolysis) and other etic terms consistent with the state-of-the-knowledge of e-waste management [10,13,72,74], this qualitative analysis could be complimented by quantitative research such as local hydrometallurgical and pyrolysis processing capabilities, chemical stability of decaying electronic components, other health and environmental risks associated with refurbishing and decay of materials in the islands, and the carbon implications of transportation of e-waste along the material’s life cycle to mainland Ecuador. Importantly, potential cancer risks in proximity to WEEE disposal sites in Santa Cruz were mentioned by numerous interviewees, though it did not fit within the scope of this particular project. Therefore, health implications associated with e-waste would be a welcome addition to future quantitative and qualitative analyses in Galapagos.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to understand waste management issues in the Galapagos Islands. A combination of key informant interviews, participant observation, and archival data analysis permitted triangulation of several findings and conclusions. First, this analysis highlights how space, isolation, limited capital and lack of infrastructure in island settings create limitations for e-waste management using circular economy principles. As Henrysson & Nuur [42] point out, more studies need to address “the CE model in a regional context” (p. 150). Second, it demonstrates the diverse and polycentric “institutional, financial, technical and educational” arrangements involved with managing such materials [3] (p. 546) and how this relates to power differentials regarding the ability to engage in more sustainable e-waste management practices. Third, it reveals how even when consensus concerns about e-waste impacts are present, these diverse arrangements and power differentials can contribute to a lack of consensus regarding the most effective and sustainable paths forward for improved e-waste management.

These findings can be used by institutions in the Galapagos to assess their contribution to WEEE accumulation on the islands. They can also be used by decision-makers to identify where the flow of materials is stalled and why. In doing so, governing entities can pinpoint where to provide financial and logistical support to achieve a CE of e-waste. For future management of WEEE in Galapagos, and elsewhere, implementing a circular model will be essential [13]. This study can be complimented by additional quantitative research, as previously mentioned, by principles of producer responsibility, and by helpful guides for creating WEEE management systems and policies [67].

With population and tourism growth increasing exponentially in Galapagos and other island settings, institutions responsible for waste management are struggling to keep pace with material flows [3,5,7,8,64]. With concerns for the implications of waste accumulation in island settings on human and environmental health poised to increase in the coming years, the type of research undertaken here is thus urgently needed. As a critical first step towards describing the current systems and envisioning future scenarios, this work helps the CDF take this important first step and ideally inspires other conservation and sustainable development-forward organizations to take similar steps in other island settings. Recent articles such as [11,66,67] have analyzed the adoption of CE for solid and e-waste management in SIDs and SNIJs in Africa, Indonesia, and the Caribbean. This study adds the region of South America and the addition of PIE as a theoretical framework to the growing conversation around waste management on islands. As such, this work will be of interest to scholars and practitioners interested in formulating solutions to growing waste management challenges in other SIDs and SNIJs settings around the globe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.J., M.J.B.-P. and C.A.H.; methodology, M.E.J.; formal analysis, M.E.J.; investigation, M.E.J.; resources, M.E.J., M.J.B.-P. and C.A.H.; data curation, M.E.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.J.; writing—review and editing, M.E.J., M.J.B.-P. and C.A.H.; visualization, M.E.J.; supervision, M.J.B.-P. and C.A.H.; project administration, M.E.J., M.J.B.-P. and C.A.H.; funding acquisition, M.E.J. and C.A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under Grants No. BCS#2020555, DGE#2105726, and BCS#2417019. A Fellowship in Sustainability Science at the Charles Darwin Foundation also supported the work undertaken here.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Penn State University (STUDY00015419, 8 June 2020 & STUDY00022651, 14 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and privacy concerns regarding participant consent process.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all interviewees for their candid perspectives and the Charles Darwin Research Station for administrative and technical support related to this project. This publication is contribution number 2764 of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Circular Economy |

| IE | Industrial Ecology |

| PIE | Political Industrial Ecology |

| WEEE | Waste electrical and electronic equipment |

| EEE | Electrical and electronic equipment |

| LOREG | Ley Orgánico del Régimen Especial de Galápagos (Galapagos Special Organic Law) |

| CGREG | Consejo de Gobierno de Régimen Especial de Galápagos (Governing Council of Galapagos) |

| PNG | Parque Nacional Galápagos (Galapagos National Park) |

| CDF | The Charles Darwin Foundation |

References

- Agamuthu, P.; Herat, S. Sustainable waste management in Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 681–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri-Fenech, M.; Oliver-Solà, J.; Farreny, R.; Gabarrell, X. Where do islands put their waste?—A material flow and carbon footprint analysis of municipal waste management in the Maltese Islands. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohee, R.; Mauthoor, S.; Bundhoo, Z.M.A.; Somaroo, G.; Soobhany, N.; Gunasee, S. Current status of solid waste management in small island developing states: A review. Waste Manag. 2015, 43, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschenes, P.J.; Chertow, M. An island approach to industrial ecology: Towards sustainability in the island context. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.M.; Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M. Solid Waste Management in Small Tourism Islands: An Evolutionary Governance Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, M. Island tourism: Past, present, and prospects. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Ashton, W.; Arakaki, Y.; Hanaki, K.; Nagashima, S.; Malone-Lee, L.C. Island Waste Management Systems: Statistics, Challenges, and Opportunities for Applied Industrial Ecology. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Small Island Developing States Waste Management Outlook; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Widmer, R.; Oswald-Krapf, H.; Sinha-Khetriwal, D.; Schnellmann, M.; Böni, H. Global perspectives on e-waste. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 436–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodship, V.; Stevels, A.; Huisman, J. Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Handbook; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gollakota, A.R.K.; Gautam, S.; Shu, C.-M. Inconsistencies of e-waste management in developing nations—Facts and plausible solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Singh, S.J.; Habib, K. How big is circular economy potential on Caribbean islands considering e-waste? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, V.; Baldé, C.P.; Kuehr, R.; Bel, G. The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, Flows and the Circular Economy Potential; United Nations University (UNU)/United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR)—Co-hosted SCYCLE Programme, International Telecommunication Union (ITU) & International Solid Waste Association (ISWA): Bonn, Germany; Geneva, Switzerland; Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parajuly, K.; Kuehr, R.; Awasthi, A.K.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Lepawsky, J.; Smith, E.; Widmer, R.; Zeng, X. Future E-Waste Scenarios; StEP Initiative, UNU ViE-SCYCLE, and UNEP IETC: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akese, G.; Little, P. Centering the Korle Lagoon: Exploring blue political ecologies of E-Waste in Ghana. J. Political Ecol. 2019, 26, 448–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barapatre, S.; Rastogi, M. e-Waste Management: A Transition Towards a Circular Economy. In Handbook of Solid Waste Management; Baskar, C., Ramakrishna, S., Baskar, S., Sharma, R., Chinnappan, A., Sehrawat, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, D.N.; Brune Drisse, M.-N.; Nxele, T.; Sly, P.D. E-Waste: A Global Hazard. Ann. Glob. Health 2014, 80, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouyamanesh, S.; Kowsari, E.; Ramakrishna, S.; Chinnappan, A. A review of various strategies in e-waste management in line with circular economics. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 93462–93490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.; Goldizen, F.C.; Sly, P.D.; Brune, M.-N.; Neira, M.; Van Den Berg, M.; Norman, R.E. Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: A systematic review. Lancet Glob. Health 2013, 1, e350–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withanage, S.V.; Habib, K. Life Cycle Assessment and Material Flow Analysis: Two Under-Utilized Tools for Informing E-Waste Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osibanjo, O.; Nnorom, I.C. The challenge of electronic waste (e-waste) management in developing countries. Waste Manag. Res. 2007, 25, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meylan, G.; Lai, A.; Hensley, J.; Stauffacher, M.; Krütli, P. Solid waste management of small island developing states—The case of the Seychelles: A systemic and collaborative study of Swiss and Seychellois students to support policy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 35791–35804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldacchino, G. (Ed.) Archipelago Tourism: Policies and Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). Censo de Población y Vivienda: Reporte Técnico; INEC: Quito, Ecuador, 2022; Available online: https://www.censoecuador.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/CPV_2022_Reporte_Tecnico_mar2024.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Mena, C. El suministro de alimentos en Galápagos: Enlazando agricultura, importaciones y turismo para crear escenarios futuros. In Symposium 60 Years of Science and Research; Galapagos National Park, Charles Darwin Foundation: Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección del Parque Nacional de Galápagos (DPNP). Informe Anual de Visitantes 2023; Dirección del Parque Nacional de Galápagos (DPNP): Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2023; Available online: https://galapagos.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/INFORME_ANUAL_VISITANTES-2023_WEB-LQ.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Dirección del Parque Nacional de Galápagos (DPNP). Informe Anual de Visitantes 2024; Dirección del Parque Nacional de Galápagos (DPNP): Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2024; Available online: https://galapagos.gob.ec/2024/informe_anual_visitantes_2024.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hunt, C.A. The Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. In Overtourism: Lessons for a Better Future; Honey, M., Frenkiel, K., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo de Gobierno de Régimen Especial de Galápagos (CGREG). Tasa de Ingreso al Parque Nacional Galápagos; CGREG: Isla San Cristóbal, Ecuador, 2025; Available online: https://www.gobiernogalapagos.gob.ec/tasa-ingreso-parque-nacional-galapagos/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Hunt, C.A.; Barragán-Paladines, M.J.; Izurieta, J.C.; Ordóñez, L.A. Tourism, compounding crises, and struggles for sovereignty. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2381–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. E-waste: Generación de Residuos-e en Ecuador. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1218688/generacion-residuos-electronicos-ecuador/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ministerio del Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica (MAATE). MAATE Gestionará 14 Toneladas de Residuos y Desechos Especiales Peligrosos Provenientes de Galápagos; MAATE: Quito, Ecuador, 2022; Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/maate-gestionara-14-toneladas-de-residuos-y-desechos-especiales-peligrosos-provenientes-de-galapagos/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Morales-Urrutia, D.; Pereira, Á. A Review of E-Waste Management and a Proposal for Effectively Implementing a Circular Model in Ecuador. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, e240053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The great acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winans, K.; Kendall, A.; Deng, H. The history and current applications of the circular economy concept. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Eiroa, B.; Fernández, E.; Méndez-Martínez, G.; Soto-Oñate, D. Operational principles of circular economy for sustainable development: Linking theory and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens III, W.W. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, K. The limits of the loops: Critical environmental politics and the Circular Economy. Environ. Politics 2021, 30, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular economy—From review of theories and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, P.; Gedam, V.; Unnikrishnan, S.; Verma, S. Circular economy in built environment—Literature review and theory development. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosch, R.A.; Gallopoulos, N.E. Strategies for Manufacturing. Sci. Am. 1989, 261, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrysson, M.; Nuur, C. The Role of Institutions in Creating Circular Economy Pathways for Regional Development. J. Environ. Dev. 2021, 30, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Ritala, P.; Mäkinen, S.J. Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Hjaltadóttir, R.E.; Hild, P. Practising circles: Studying institutional change and circular economy practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickren, G. Geographies of E—waste: Towards a Political Ecology Approach to E—waste and Digital Technologies. Geogr. Compass 2014, 8, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power: A Radical View, 3rd ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2021; pp. 19–193. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, J.P.; Cousins, J.J.; Baka, J. Political-industrial ecology: An introduction. Geoforum 2017, 85, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.K.; Li, J.; Koh, L.; Ogunseitan, O.A. Circular economy and electronic waste. Nat. Electron. 2019, 2, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, V.; Sahakian, M.; van Griethuysen, P.; Vuille, F. Coming Full Circle: Why Social and Institutional Dimensions Matter for the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.J.; Munro, A.J. Waste Management in the Small Island Developing States of the South Pacific: An Overview. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 1999, 6, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yken, J.; Boxall, N.J.; Cheng, K.Y.; Nikoloski, A.N.; Moheimani, N.R.; Kaksonen, A.H. E-Waste Recycling and Resource Recovery: A Review on Technologies, Barriers and Enablers with a Focus on Oceania. Metals 2021, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 5th ed.; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, J.P. The Ethnographic Interview; Waveland Press, Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R.; Wutich, A.; Ryan, G.W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca (MPCEIP); Ministerio del Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica (MAATE). Estrategia Nacional de Economia Circular Inclusiva; MAATE: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2024/10/Estrategia-Nacional-de-Economia-Circular-Inclusiva-ENECI.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Villalobos, A.S.; Ruiz, A.G.; Jiménez, J.S.; Chávez, J.Q. Guía: Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado Circular; Ministerio del Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica (MAATE): Quito, Ecuador, 2022; Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2023/07/9.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Ministerio del Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica (MAATE). Ecuador Reciclará 700 Toneladas de Residuos Electrónicos y Eléctricos; MAATE: Quito, Ecuador, 2022; Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/ecuador-reciclara-700-toneladas-de-residuos-electronicos-y-electricos/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Ministerio del Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica (MAATE). Habitantes de Santa Cruz Reciclan Desechos Electrónicos; MAATE: Quito, Ecuador, 2013; Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/habitantes-de-santa-cruz-reciclan-desechos-electronicos/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Ministerio del Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica (MAATE). Reforma del Libro VI del Texto Unificado de Legislación Secundaria; MAATE: Quito, Ecuador, 2022; Available online: https://www.gob.ec/regulaciones/acuerdo-ministerial-no-061-reforma-libro-vi-texto-unificado-legislacion-secundaria (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Singh, S.J.; Elgie, A.; Noll, D.; Eckelman, M.J. The challenge of solid waste on Small Islands: Proposing a Socio-metabolic Research (SMR) framework. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 62, 101274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.B.; Johansen, M.R.; Buchard, M.V.; Glarborg, C.N. Closing the material loops for construction and demolition waste: The circular economy on the island Bornholm, Denmark. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamahefazafy, M.; Failler, P. Towards a Circular Economy for African Islands: An Analysis of Existing Baselines and Strategies. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, T.A.; Rachmawati, Y. The Prospect of Implementing Circular Economy of Solid Waste in Small Islands: A Case Study of Karimunjawa Islands District, Central Java-Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 799, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copara, M.; Pilamunga, A.; Ibarra, F.; Oyaque-Mora, S.-M.; Morales-Urrutia, D.; Córdova, P. A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis for the Design of a Traceable and Sustainable Model for WEEE Information Management in Ecuador Based on the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardter, U.T.; Oña, I.L.; Butt, K.M.; Chitwood, J. Waste Management Blueprint for the Galápagos Islands; World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Toyota: Puerto Ayora, Galapagos, Ecuador, 2010; Available online: http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/waste_mgmt_blueprint_galapagos_mar2010_final.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Ragazzi, M.; Catellani, R.; Rada, E.; Torretta, V.; Salazar-Valenzuela, X. Management of Municipal Solid Waste in One of the Galapagos Islands. Sustainability 2014, 6, 9080–9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, P.; Martínez-Moscoso, A.; Sucozhañay, D.; Paño, P.; Tello, A.; Abril, A.; Izquierdo, I.; Pacheco, G.; Craps, M. E-waste management in Ecuador, current situation and perspectives. In Handbook of Electronic Waste Management; Vara, M.N., Prasad, M., Vithanage, A., Borthakur, Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 479–515. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, S.C.A.; Ott, D.; Lora Reyes, N. Transboundary Movement of WEEE in Latin America; StEP Initiative: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Poma, P.; Polanco, M.; Usca, K.; Casella, C.; Toulkeridis, T. An Evaluation of the Public Service of the Integrated Municipal Management of Urban Solid Waste in the Galapagos and the Amazonian Region of Ecuador. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solving the E-Waste Problem: Guiding Principles to Develop E-Waste Management Systems and Legislation; United Nations University and StEP Initiative: Bonn, Germany, 2016. Available online: https://www.step-initiative.org/files/_documents/whitepapers/Step_WP_WEEE%20systems%20and%20legislation_final.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).