Abstract

Greenery and its significance in fostering sustainable urban development constitute a fundamental theme in contemporary urban planning. This study focuses on allotment gardens as a potential means of enhancing the quality of urban living environments, seeking to establish whether this form of urban greenery—often perceived as an anachronism—continues to play a meaningful role in promoting the well-being of city residents. The objective of the article was to examine whether allotment gardens exhibit the characteristics of spaces conducive to well-being within residential contexts, drawing upon scientific knowledge and expert opinions. The research employed a literature review, qualitative data analysis of material collected through individual in-depth and focus group interviews, and a final matrix analysis to assess the extent to which existing benefits satisfy contemporary demands. The findings identify current well-being features associated with allotment gardens, addressing residents’ needs regarding the benefits they offer, including recreation and leisure, and their impact on physical and mental health, as well as the formation of social relationships. Nutrition was further characterised by the self-production of healthy, affordable, and extraordinary food. The results also underscore the importance of accessibility in shaping the well-being benefits of allotment gardens, emphasising the acquisition of new competencies, the strengthening of social relations, and opportunities for health and recreation as their primary contributions.

1. Introduction

Well-being in the urban housing environment, as understood in the presented research, refers to an individual’s overall state of health and life satisfaction, encompassing physical, mental, and emotional dimensions, as well as social coexistence within a community, which together contribute to happiness and quality of life [1,2]. This topic has become a major concern for both sociologists and housing researchers in the context of today’s complex urban challenges. In considering contemporary cities and communities, it is essential to recognise not only the natural values of urban greenery but also its broader social and spatial functions [3].

Allotment gardens, which form an integral element of the green infrastructure in many European cities, embody a wide range of values. Their significance can be examined in relation to the social, economic, and spatial factors shaping residents’ quality of life. From a sociological perspective, residential well-being refers to the subjective sense of satisfaction derived from interaction with the social environment [4,5]. Research indicates that well-being is influenced by factors such as neighbourhood relations, levels of social capital, safety, and access to social infrastructure including educational, cultural, and care institutions [6,7]. Socio-economic inequalities are also critical, frequently generating disparities in quality of life [8,9]. In contrast, scholars of the residential environment often emphasise the physical and spatial characteristics of urban settlements and their effects on health and well-being, focusing on issues such as access to green spaces and their functional qualities, analogous to the functionality of dwellings and buildings [10,11]. Empirical studies demonstrate that greenery in residential areas has a positive effect on mental health and stress reduction [12,13]. Horticultural activities in cities likewise foster mental and physical health, while enhancing satisfaction with one’s living environment [14,15,16]. From the perspective of environmental psychology, the aesthetics of land use are also important, as they may significantly affect residents’ mental health and well-being [17,18]. Consequently, access to green spaces that enable horticultural practices can be interpreted as an expression of spatial justice [19,20].

The particular historical development of Warsaw, shaped by extensive destruction during the Second World War and subsequent rebuilding, produced numerous areas suitable for horticultural use. Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs) exemplify this legacy. In Poland, allotment gardens have a long-standing tradition, dating back to the late nineteenth century, when they were established as a means of supporting workers and their families, aiming to improve living conditions during rapid industrialisation. The oldest allotment garden in Warsaw, still in existence today, “Obrońców Pokoju”, was founded in 1903. After the First World War, new gardens were often created on land formerly owned by the Tsarist army, which after 1918 became property of the State Treasury. By the start of the Second World War, Warsaw already had ten allotment gardens [21].

During the socialist era, the importance of family gardens grew significantly: they served both as a government propaganda tool and as a vital source of food, recreation, and symbolic access to land for residents of large housing estates [22,23]. After 1989, productive functions gradually shifted towards recreational purposes, a change widely linked to generational differences [24,25]. Simultaneously, allotment gardens, especially those in central districts, began to be seen as sites with investment potential. In the early twenty-first century, allotment gardeners started to mobilise, emphasising the recreational, social, and ecological roles of these areas. Legal disputes over ownership and land use were addressed through the Allotment Gardens Act of 2005, along with its 2013 amendment, which established a uniform regulatory framework governing the rights of allotment holders, land use, and restrictions on the liquidation of gardens [26].

Despite ongoing development pressures, Warsaw’s allotment gardens have preserved their role as essential green spaces within an increasingly urbanised landscape. In recent years, awareness of their ecological, social, and cultural importance has grown [27,28], especially in light of climate change [29] and the need for social cohesion [30]. Their future, however, depends on balancing the demands of urban growth with the protection of their ecological and social roles. Currently, there are 154 allotment garden complexes in Warsaw. FAGs cover 17 km2, representing 2.6% of the city’s area, and are used by approximately 26,000 allotment holders (excluding their family members), which accounts for 1.7% of Warsaw’s total population [24,31]. FAGs mainly operate on land owned by the State Treasury, local governments, or the Polish Allotment Gardeners’ Association (PZD), while the allotment holders have the right to use the plots but do not own the land. Maintenance is managed by the FAG management board, elected by the allotment holders, which oversees infrastructure, finances, and order [32]. Allotment holders must pay annual fees for garden upkeep and adhere to regulations.

The need to update knowledge in this field arises from two main considerations. First, over the past five years, there has been a noticeable resurgence of interest in allotment gardens, particularly among younger Warsaw residents aged 20–30, a trend that was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 [25,33]. During this period, Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs) emerged as one of the few spaces offering opportunities for outdoor recreation due to their semi-private character. Second, municipal authorities in Warsaw initiated a new study questioning the continued presence of many FAGs in the urban landscape, advocating instead for land reallocation to residential development [34]. Although subsequent amendments to planning law temporarily halted such decisions, the preparation of a new master plan for Warsaw—without provisions for officially designated protection zones for FAGs—ensures that the issue remains highly relevant and subject to ongoing public debate.

The legitimacy of maintaining large allotment garden areas in investment-friendly locations, especially those close to the city centre with existing infrastructure, has become a matter of debate. At the same time, their rising popularity among younger generations suggests that they fulfil a unique role not easily replaced by other types of green or recreational spaces. The research presented in this article demonstrates the wide range of functions, attributes, and benefits associated with allotment gardens, which effectively complement the limited space of flats in multi-family housing estates.

The research aimed to determine the contemporary needs of allotment gardeners and the benefits they achieve from city allotment gardens, in light of scientific knowledge and expert opinions

- Accordingly, the authors posed the following research questions:Q1—What features of residential well-being are perceived in the scientific literature?Q2—What are residents’ needs regarding benefits that came from FAGs’?Q3—What do FAGs supply residents with? What benefits do they offer?Q4—Do FAGs create well-being in residential areas?

2. Materials and Methods

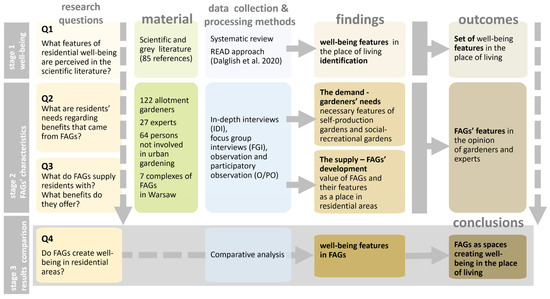

The research was carried out in three stages. In the first stage, the features of well-being in residential environments were identified through a systematic review of scientific and grey literature on well-being and urban housing contexts. The second stage focused on characterising Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs). Drawing on community surveys with allotment gardeners and experts, information was gathered regarding the perceived value of FAGs and their role as components of residential areas.

In the third stage, the results of the first two stages were compared to determine which features reported by allotment gardeners and experts, and identified in the gardens themselves, corresponded with recognised well-being attributes of residential environments. This triangulated approach demonstrated that FAGs can be understood as spaces that foster well-being within the residential context (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the research procedure. Source: own elaboration. READ approach adopted from Dalglish et al. [35].

2.1. Stage 1—Well-Being Features in the Place of Living Identification

The search for well-being characteristics in the context of residential environments required a comprehensive review of foundational data. The literature analysis drew on three academic databases: Scopus, ScienceDirect (SD), and Web of Science (WoS). In addition, grey literature concerning principles and standards of well-being in residential contexts in various cities worldwide—such as Bursa (Turkey), Thessaloniki (Greece), Oslo (Norway), Famagusta (Cyprus), Winnipeg (Canada), and Minneapolis (United States)—was also considered.

The READ approach [35] was employed as the method of analysis. This involves four steps: reading the material (Read your materials), extracting relevant data (Extract data), analysing it (Analyse data), and distilling the findings (Distil your findings). Originally developed for document analysis, the READ method has also proven useful in examining both grey and scientific literature. An initial meta-analysis, based on keyword searches including well-being, housing satisfaction, residential satisfaction, quality of life, happiness, community well-being, mental health, and food security, produced 85 records, which were subsequently examined using this approach. A summary of the literature analysis is provided in the Appendix A.

Although the reviewed material derived from diverse contexts and regions, the broad range of well-being features identified offered a robust foundation for subsequent research, while minimising the risk of subjective bias rooted in specific local contexts.

2.2. Stage 2—The Survey on ‘Demand’ and ‘Supply’ of Benefits Offered by the Allotment Gardens

To determine the value of Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs) and their characteristics as living spaces from the perspective of allotment gardeners and experts, a community survey was conducted. The study employed three complementary methods:

- Individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) [36]—a total of 149 interviews were conducted, each lasting between 45 and 75 min. The sample included 122 allotment gardeners from seven FAG complexes in Warsaw: FAG Kinowa and FAG Jerzego Waszyngtona (30 respondents), FAG Obrońców Pokoju (23), FAG Pratulińska (20), FAG Rakowiec (27), FAG Sielanka (14), and FAG Służewiec (8). In addition, interviews were carried out with six municipal officials (experts in ecology, climate, urban planning, architecture, and cultural animation related to community gardens), four respondents active in community gardening, six community gardeners who were also NGO activists, and eleven NGO activists not directly engaged in gardening.

- Focus group interviews (FGIs) [37]—the purposive sample comprised 64 individuals aged 20–30, studying humanities or social sciences at a university in Warsaw. The sessions lasted approximately 120 min. While not active in urban gardening, most had limited experience with balcony or windowsill cultivation. Although not representative of all non-gardeners in Warsaw, this group was chosen for its educational background, which was expected to foster sensitivity to and understanding of social issues—central to the study’s aims.

- Observation and participatory observation (O/PO) [38]—were conducted to confirm and further identify urban gardening functions. O/PO took place during gardening activities in communal spaces, public events, and training sessions, involving gardeners who had previously participated in IDIs. This approach provided insights into behaviours in natural settings, as well as the ways participants expressed views and emotions, offering a deeper understanding of the social dynamics under study [39].

Data analysis involved transcription of the interview recordings (.mp3 files) using the Trint application, followed by coding using an open tag list. Following the principles of grounded theory [40,41], the coding remained open throughout the process, allowing theory to emerge from the data itself. Using a multi-case comparison method, general categories were generated, aligned with the content of the material, and social processes were described until saturation was reached. Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5 in Appendix A summarise the interview analysis. Triangulation was applied in both data collection and analysis, involving multiple sources and the engagement of a diverse research team to ensure varied perspectives and methodological robustness [42,43].

Regarding sampling strategy, respondents for the IDIs were recruited using the snowball method. An initial set of stakeholders connected with FAGs in Warsaw was identified, including urban gardeners, community activists, municipal officials, and experts in urban planning, architecture, natural and horticultural sciences, earth sciences, social sciences, and environmental and climate policy. Respondents often belonged to multiple categories, reflecting overlapping roles. Each participant was asked to recommend further respondents with relevant expertise, thereby expanding the sample. The recruitment strategy ensured diversity in age, gender, and educational background, while prioritising the saturation of results [44].

2.3. Stage 3—Well-Being Supply—The Benefits in FAGs

Based on the literature review, the well-being features identified in Stage 1 were systematically compared, in tabular form, with those obtained in Stage 2 through the social survey. This comparison confirmed that Warsaw’s Family Allotment Gardens fulfil the criteria of well-being spaces within the residential environment.

3. Results

3.1. Features Influencing the Sense of Well-Being at the Place of Living

A review of existing literature reveals that definitions of subjective well-being are found across various scientific disciplines, including economics [45,46,47], epidemiology [48], and psychology [13,49]. They also appear in studies related to public policy [50,51,52,53], housing [54,55], and urbanisation [56,57]. Neighbourhood satisfaction results from the interaction of three main factors: socio-demographic attributes, subjective neighbourhood assessments, and objective neighbourhood features [58]. Constraints that limit a household’s ability to adapt have been classified into categories such as resources (income and human capital), predisposition (apathy or activism), organisation (problem-solving skills), discrimination (based on race, gender, or socio-economic status), market conditions, and cultural norms [59]. Housing adaptation theory suggests that, despite these constraints, dissatisfaction with housing tends to decline over time as households ‘assimilate’ into their neighbourhoods [60,61]. Descriptive statistics and univariate analyses are often employed to explore the links between well-being and individual factors (such as gender, age, marital status, ethnicity, homeownership, length of residence, education, income, and social capital) and neighbourhood conditions (including safety, local services, social capital, and social cohesion). Therefore, the debate around ‘good housing’ centres on understanding the causal relationships between housing and subjective well-being [62]. Some researchers contend that individual characteristics (like health or financial situation) are more closely associated with well-being [48,63,64]. Others challenge this ‘dualistic’ perspective, arguing that the effects of individual and contextual factors are inseparable and that well-being should be viewed as a network of mutually reinforcing relationships between personal traits, the community, and the environment [51,65]. Beyond the physical features of dwellings, well-being can also be influenced by residents’ rights and responsibilities regarding their living environment, typically linked to dwelling ownership [66].

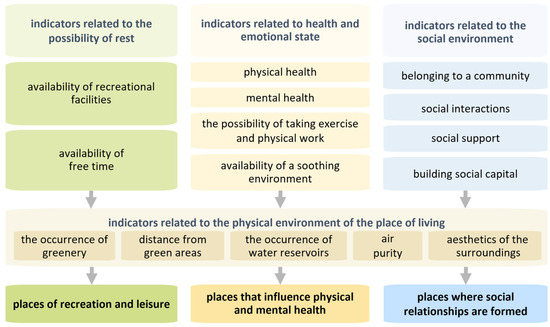

In some studies, well-being has been primarily defined through indicators such as green space availability, cleanliness, accessibility, safety, and perceived importance within the local environment [67]. These studies often measure the area of green space surrounding each participant’s home—including parks, woodlands, scrubland, and other publicly accessible natural areas—with stress and psychological well-being as the main outcome variables. The study we identified as the most systematic addressed indicators across several domains—leisure, health and emotional responses, social relationships, residential environment, and work and travel. These domains were proposed as a framework for structuring the interface between objective environmental conditions and the subjective feelings of space users, who are highly sensitive to individual factors. The researchers examined how neighbourhood satisfaction relates to components of subjective well-being and presented a model testing the links between satisfaction with commuting, neighbourhood, housing, and other life domains and subjective well-being [68]. This approach proved particularly useful for our research on the well-being of allotment garden users. Following this study and our review of the literature on well-being, we compiled a list of the most frequently cited features used to assess well-being in relation to inhabited space and its surroundings (Figure 2). Indicators relating to work and travel were excluded, as they fall outside the scope of gardening and allotments. While work and travel could be tangentially linked to allotment gardens (for instance, working in the garden or travelling to it), Mourtidis’ framework [68] isolates broad spheres of urban life in which employment is treated as an income-generating activity and commuting as routine travel to work or school. In our research, the topic of gardening arose within the health domain, whereas commuting appeared in the leisure domain. In response to Question 1, the indicators most frequently mentioned by researchers of residential well-being can be readily assigned to four spheres. As the physical environment continually interacts with the other three spheres to create well-being, our research focused on Family Allotment Gardens as:

- -

- Places of recreation and leisure,

- -

- Places that influence physical and mental health,

- -

- Places where social relationships are formed.

Figure 2.

Features of residents’ well-being. Source: own elaboration.

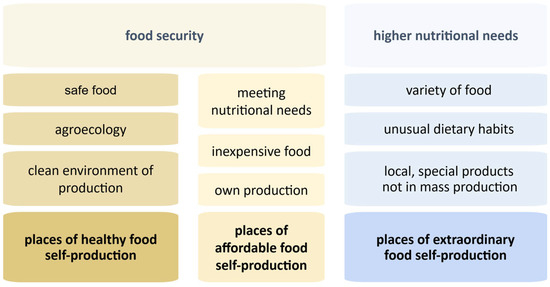

However, the above collection did not fully address our interests, as the topic of food self-production had been a core focus from the outset. In this context, ‘food self-production’ refers exclusively to the provision of food for personal nutritional needs rather than to commercial agricultural production. Although health factors are frequently cited among the determinants of well-being, we found no studies directly linking place of residence with nutrition. Researchers rarely examine how the living environment shapes the satisfaction of one of the most basic biological needs, even though food security strongly influences health and is closely tied to financial circumstances.

When investigating allotment gardens, it is impossible to overlook their connection to food self-production and its implications for food security, understood as ensuring access to sufficient and good-quality food in both physical and economic terms [69]. The satisfaction of nutritional needs and its contribution to a sense of security among urban dwellers have been observed historically, including in pre-industrial and even prehistoric urban structures [70]. The modernist model—which conceptualised urban life as distinct from rural life and regarded urban food cultivation as obsolete in a futuristic city—now appears outdated. Urban food self-production should be viewed not as the antithesis of the city, but as an integrated activity that offers accessible, energy-efficient ways of producing food and reducing the length and complexity of supply chains.

In this light, researchers have examined the effects of small-scale urban cultivation on individual self-sufficiency and food security [71], as well as the broader benefits of urban gardening in its diverse forms [72,73,74]. The COVID-19 pandemic further intensified concerns about food access and stimulated initiatives promoting food self-sufficiency [75,76,77]. The importance of urban gardens as key elements of nearby nature has been widely acknowledged, with reported benefits including enhanced food security, support for household budgets, improved mental health and well-being, strengthened social interaction, and positive effects on local community development and activation [78,79]. Food security also encompasses preventing emergencies and severe hunger, as well as fulfilling higher-order needs such as access to organic, ecological or otherwise scarce food products.

The revival of traditional cultivation practices contributes to biodiversity and, consequently, soil health, accommodating diverse species, root structures and rich organic matter [80]. Viewed globally, this trend towards food self-production aligns with the concept of agroecology—simultaneously a science, a practice and a social movement—which fosters grassroots and regional processes and strengthens community agency [81]. For instance, horticulture and community food cultivation have proved crucial for Alaska Natives [82], offering affordable access to high-quality fruits, vegetables and other locally grown produce, while Havana represents another well-documented case [83]. As a strategic supplement to the food supply chain, urban gardening increases resource diversity. In contemporary gastronomy, renewed interest in traditional and regional cuisine has led chefs to revisit local dishes, further stimulating demand for locally sourced produce [84].

Thus, continuing our response to Question 1, the additional literature review enabled us to broaden our research framework to three areas (Figure 3), viewing Family Allotment Gardens as:

- -

- Places of healthy food self-production;

- -

- Places of affordable food self-production;

- -

- Places of extraordinary food self-production.

Figure 3.

Features of residents’ well-being in the area of nutrition. Source: own elaboration.

3.2. Demand for the Determinants of a Sense of Well-Being in the Place of Living, Created by Family Allotment Gardens

The second stage of the research revealed that users of Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs) can be divided into several groups according to the needs they satisfy through their plots. These groups can be distinguished by the functions of their allotments that they regard as most important. The functions identified include socio-recreational uses—such as leisure, play and psychological benefits—and productive uses, primarily food self-production (vegetables, herbs, fruit and, more rarely, small-scale animal husbandry). Even within a single plot, multiple generations may use the space in different ways, so that one site can fulfil several functions simultaneously. The way an allotment is used therefore reflects the diverse motivations and needs guiding individual users. Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A present excerpts from interviews with allotment holders and experts, illustrating the empirical basis for the summary below.

Answering Question 2, the motivations and needs most frequently mentioned by respondents in relation to socio-recreational functions were:

- -

- The need for an inexpensive method of recreation and leisure, where the financial aspect related to lifestyle and lack of free time are important.

- -

- The need to take care of mental and physical fitness is important for many younger and active people.

- -

- The needs related to integration, belonging to a group (sociability), motivations to make friends, build social relationships, family and friendship ties.

By contrast, with respect to self-production functions, the motivations and needs most frequently identified by respondents were:

- -

- Self-production of healthy food—for personal and family consumption, motivated by the perception that it is increasingly difficult to purchase healthy, organic food in Polish shops. Respondents emphasised the importance of growing food from unprocessed mineral or biological sources without the use of chemical fertilisers or pesticides.

- -

- Self-production of inexpensive food—to offset rising food prices, which place a growing burden on the budgets of allotment holders and their families, many of whom are not among the most affluent.

- -

- Self-production of extraordinary food—cultivating varieties not widely available commercially, including heirloom or regional species once grown by earlier generations (e.g., parsnips, rutabagas, Jerusalem artichokes, rare apple varieties). New and distinctive varieties, such as multicoloured carrots, stem lettuce or uncommon herbs, were also mentioned. Respondents highlighted how growing rare or unusual plants fosters community, facilitates the exchange of knowledge and skills, preserves tradition and strengthens intergenerational ties, while also enhancing the diversity and quality of yields.

3.3. Supply of the Benefits of FAGs and Their Facilities

Another component of the survey involved assessing the potential of Family Allotment Gardens to meet the identified demand, as perceived by respondents in terms of the availability of spatial elements and their functions.

3.3.1. Accessibility

When examining how Warsaw residents perceive their ability to satisfy their gardening needs through the use of Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs), the key factor is access to gardening space and activities, which can be assessed across several dimensions (Appendix A Table A3):

- -

- Land ownership—the availability of land for gardening—understood as the right to use and manage it—is a critical factor in all horticultural activities. Many FAGs operate on land with unresolved legal status, exposing them to the risk of liquidation. This uncertainty can discourage potential users. Current allotment holders, however, experience some sense of security because access is granted on the basis of lease agreements.

- -

- Goods ownership—linked to plot ownership is ownership of crops and equipment. FAGs are fenced and access is usually restricted, making them relatively resistant to encroachment. Nonetheless, thefts occur, particularly outside the main growing season (autumn and winter), when plots are less frequented and darkness falls earlier. Respondents reported losses ranging from tools and metal objects to occasional theft of crops. Some interviewees claimed that theft problems are sometimes underestimated by garden management. Inadequate security may also lead to vandalism or visits from individuals in crisis of homelessness.

- -

- Proximity to residence—originally, allotment gardens were intended to be located near the homes of their target users—urban workers [85]. This remains largely the case: many FAG users live nearby and see this proximity as a major advantage. The vast majority of interviewees stressed that closeness to their home facilitates their engagement in gardening activities.

- -

- Financial availability—allotment holders are obliged to contribute to the operating costs of the FAG attributable to their plot. These fees cover investment, repairs and ongoing maintenance; utilities (electricity, heat, gas and water) related to public facilities; insurance, taxes and public levies; cleanliness and order; and management costs [86].

- -

- Accessibility for outsiders—none of the experts interviewed supported the wholesale abolition of allotment gardens. Opinions differed, however, regarding the degree to which FAGs should be opened to the public. Most experts accepted some level of access to common areas, either as walking spaces or during specific organised events. Some highlighted ongoing initiatives by NGOs and the arts community to open up FAGs, while others argued that individual plots should remain under the exclusive control of allotment holders to preserve tradition and maintenance standards. The survey also revealed that many allotment gardeners are themselves open to the idea of expanding FAGs and increasing public accessibility.

3.3.2. Benefits from FAGs

Another aspect examined was the actual benefits that residents derive from Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs) through their interaction with the natural and social environment. The survey highlighted the wide range of functions that allotment gardens provide to their users (Appendix A Table A4):

- -

- Health and recreation—allotment gardens support health through physical activity and regular work, provide opportunities for recreation and leisure, and facilitate contact with nature. Activities must be carried out at a specific time and with some regularity; this ethos of steady commitment underpins the allotment-holder tradition. Interviewees compared this obligation to ‘adopting an animal’: while gardening can be enjoyable and recreational, it also involves responsibility. In today’s social and economic context, maintaining such commitment is increasingly challenging.

- -

- Enhancing gardening competencies—FAGs hold socio-educational importance, fostering creativity and maintaining a form of socio-ecological memory. When asked about the sources of their gardening knowledge, allotment holders most often cited the Internet, books, magazines, and television. Introductory training or workshops organised by FAG boards were rarely mentioned, and some respondents reported never having heard of such initiatives. According to interviewees, ‘allotment knowledge’ is often transmitted across generations or exchanged between gardeners, with experienced users playing a vital mentoring role. Many also learn through direct experimentation. Respondents emphasised that the most valuable knowledge is gained through personal effort rather than easily available information.

- -

- Social relations—allotment gardens play a long-standing role in community building, strengthening interpersonal ties and fostering a sense of connection to place. Respondents noted that the form and intensity of social interaction depend on the socio-cultural specificity of each FAG, reflecting its composition of individual knowledge, skills, attitudes, beliefs and values, as well as its history, customs and practices. This cultural transmission shapes how relationships evolve. Two contrasting styles of FAG use emerged from the interviews: ‘privatised’ versus ‘community’. In the former, common areas are minimal and purely utilitarian (pathways, waste segregation), while in the latter, shared spaces are more developed physically (facilities for gatherings and integration) and symbolically (as spaces of collective meaning). These differences influence how individual plots are organised and used. Regardless of style, relatively few people typically work a single plot, ranging from a lone enthusiast to a small group of close family members.

- -

- Consumption—FAGs provide flowers, herbs, vegetables, fruit, and mushrooms. Respondents distinguished between traditional and modern self-production models. The traditional approach, dating back to employee allotment gardens—the predecessors of FAGs—maintains a balance between cultivation and recreation (approximately one-third fruit and vegetables, one-third ornamental planting, and one-third leisure space). One interviewee described this as the ‘granny garden’ model, which, despite its name, remains popular with gardeners of all ages.

3.3.3. Equipment of FAGs

The interviews with allotment holders and experts also explored users’ opinions regarding the condition of Family Allotment Garden (FAG) facilities as functional entities (Appendix A Table A5). FAG management is responsible for maintaining infrastructure, order and cleanliness in communal areas, and for equipping the gardens with essential facilities, including perimeter fencing; garden paths and roads; parking spaces; utility yards; recreation and sports areas; children’s playgrounds and other common-use spaces; buildings; hydro-boiler stations; sanitary facilities; garden greenery and protective green belts; as well as water, electricity and other utility networks. Management is also obliged to ensure that persons with motor disabilities can access their plots by vehicle without obstruction [86].

Numerous concerns emerged during our study about the discharge of these responsibilities. Cleanliness and tidiness were among the most frequently raised issues. Problems reported included: insufficient rubbish bins; lack of specific containers (e.g., for green waste); bins located too far from plots; irregular waste collection; lack of waste segregation or incorrect segregation; the practice of bringing household waste for disposal at the FAG; littering of publicly accessible alleys; and contamination with dog faeces. Respondents also highlighted inadequate tree maintenance, deficiencies in small-scale architecture of communal areas, neglected plots and a lack of consequences for non-compliant allotment holders. However, these problems were not universal—some FAGs were positively assessed by users regarding order and cleanliness. Sanitation emerged as a related concern. Not all FAGs are equipped with adequate facilities, making plot use more difficult. Respondents also drew attention to the condition of pavements and equipment in common areas, particularly small architectural features, lighting, public toilets, bins for waste and animal faeces, benches and bicycle racks. The need for infrastructure supporting social integration—such as common rooms—was repeatedly mentioned. According to some allotment holders and authors [87,88], creating such facilities would be beneficial. Given the risk of theft and prevailing climatic conditions for much of the year, allotment holders preferred equipment that could be stored within their garden gazebos (e.g., seats, hammocks, tables, barbecues, folding gazebos, sports equipment, inflatable pools).

Summarising these findings (Section 3.3, answering Question 3), respondents identified a wide array of benefits associated with FAGs. These included: relatively high security of tenure and protection of goods; proximity and ease of access; affordability of acquisition and maintenance; reasonable control over the area; positive effects on health and recreation; opportunities for gardening education; community-building and social relations; and the development of food self-production.

3.4. The Impact of the Supply of Beneficial Features of FAGs and Their Facilities on Meeting the Demand in the Scope of Determinants of Residents’ Well-Being

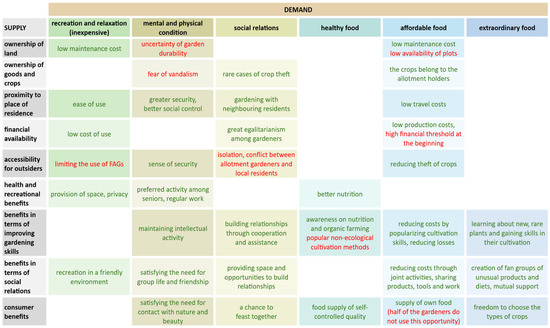

In the third phase of the research, we compared six domains of residents’ needs—whose fulfilment significantly influences their well-being and whose importance was confirmed by respondents—with the advantages (and disadvantages) of Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs) and the benefits users derive from them. The availability of these benefits can affect the extent to which the identified needs are met. Analysis of the collected data revealed several correlations, highlighting areas of demand that FAGs can satisfy particularly well, as well as a few cases where their characteristics hinder demand satisfaction.

The most comprehensive answer to Question 4 is illustrated in the proposed matrix (Figure 4). Overall, the basic demand for social and recreational functions appears to be well addressed by FAGs. However, analysis of respondents’ statements revealed variations between different gardens (Appendix A Table A1).

Figure 4.

Well-being matrix—the visualisation of strengths (green text) and weaknesses (red text) of benefits’ supply from FAGs vs. demand caused by resident’s needs. Source: own elaboration.

The matrix shows that most of the gardeners’ demands are well met across all areas of supply, encompassing both socio-recreational and self-production needs. In the second domain, however, aspects linked to accessibility respond only weakly to issues of healthy or unusual food. Most other cells of the matrix are populated with positive findings. The question of accessibility for outsiders produced more ambiguous results. On the one hand, restrictions enhance the safety of people and crops; on the other, they limit the social and recreational potential of FAGs. Allotment holders’ goals and interests are sometimes oriented less towards establishing social ties with other gardeners or neighbouring residents than towards privacy and self-use.

Other reservations identified were relatively balanced. Although acquiring and maintaining a plot can be complex, respondents generally considered FAGs financially affordable. Perceived safety hazards in densely used gardens were not supported by evidence, with reported incidents of theft being rare. Despite frequent declarations that self-production functions are in decline, our findings show that most features of FAGs continue to support food self-production. While respondents noted the costs of establishing and maintaining a plot, which makes home-grown produce difficult to describe as inexpensive, the availability of these foods—obtained through personal effort—was widely appreciated.

Answering Question 4, it can be stated that the needs identified by our respondents appear to be met at a highly satisfactory level through the benefits and services provided by Family Allotment Gardens, which in turn contribute positively to well-being in the place of residence.

4. Discussion

4.1. Features of Residential Well-Being at the Place of Living Are an Interdisciplinary Concept, Depending Not Only on the Quality of the Environment

As early as the late 1960s [89], theories of neighbourhood satisfaction emphasised the standard view that an individual’s satisfaction with their neighbourhood derives primarily from the congruence between their actual and desired circumstances. A key implication of housing adjustment theory is that choice plays a decisive role in determining satisfaction: the more options individuals have in selecting where they live, the more likely they are to reside in a place compatible with their needs and preferences [59]. For example, according to housing adjustment theory [60], individuals evaluate their housing in relation to cultural norms regarding housing standards and neighbourhood conditions, alongside their personal and family needs. When the current housing situation approximates these cultural norms or family aspirations, satisfaction is higher; conversely, a mismatch between the two generates dissatisfaction.

The multiple origins of this theory underline its inherently interdisciplinary character, which can be regarded as one of its strengths. Yet this interdisciplinarity also constitutes a weakness: efforts to create a universal description of neighbourhood satisfaction have revealed considerable variation in definitions [52,90] and approaches [91,92,93]. Measuring satisfaction with one’s residential environment is therefore far from straightforward. Researchers may use direct questions such as ‘To what extent are you satisfied with…?’, but face parallel difficulties in defining objective satisfaction levels [92]. Some studies adopt simple definitions and measures [90,94], focusing on life satisfaction, while others emphasise psychological factors [8,49,63] considered fundamental to subjective well-being. Indicators such as agency, self-esteem, social identity and similarity have been used to assess the effects of housing change [95].

From this, it may be inferred that the space of allotment gardens indirectly influences several indicators of life satisfaction. Consequently, the features of Family Allotment Gardens can be viewed as indicative of the quality of life within particular residential environments.

4.2. Residents’ Needs Regarding Benefits That Came from FAGs’ Focus on Growing Food, the Self-Therapy, Activeness and Sociability

Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs) often provide a practical response to the financial constraints faced by many households that cannot afford holidays, weekend trips, a house with a private garden or a plot of land outside the city. In this respect, FAGs play a significant role in promoting spatial justice, even though they are not public spaces in the strict sense [18,19].

Situated within residential areas, allotment gardens enable younger and more active users to escape the pressures of everyday life and long working hours, to relax, reduce stress and counteract information overload or ‘fear of missing out’ (FOMO) [96]. For many, cultivating an allotment functions as a form of self-therapy, closely linked to childhood memories and primary socialisation, as well as associations with loved ones, carefree leisure and happy family life [97,98]. For older people, who are often no longer economically active, the opportunity for food self-production and traditional recreation provides activity, purpose and a sense of being needed [99]. In many cases, the allotment is also an important component of family identity [21].

The specific character of allotment gardens fosters close connections and the formation of small local communities. Gardeners often describe their community as a family, where members support one another, share advice, lend tools and exchange crops or recipes. Beyond their instrumental dimension, these practices also serve socialising and integrative functions [97,100]. This broadly non-commercial exchange shapes a culture in which attitudes, norms, values and beliefs are transmitted to younger generations. By contrast, individuals who primarily use the plots for recreation and do not cultivate them are more likely to report disengagement from the life of the garden community and the sharing economy more broadly.

Intergenerational interaction among people with diverse skills and forms of capital—social, economic, cultural and educational—as well as differing lifestyles, enables participants to acquire both ‘hard’ competences (such as cultivating and processing produce, repairing garden equipment) and ‘soft’ competences (such as communication, cooperation and conflict resolution). FAGs offer a secure and supportive environment in which participants can work collaboratively and build networks. This safe and welcoming atmosphere is particularly attractive to young families with children [87], and relationships forged within the gardens often extend beyond their physical boundaries and may even be ‘inherited’ by successive generations [12].

Rising awareness among allotment holders of the health benefits of nutritious food has strengthened the emphasis on growing healthy produce [88]. Other studies confirm that the value of organically grown fruit and vegetables is particularly recognised by relatively young people with small children, as well as by those over fifty [99,101]. Many explicitly state that they grow crops for the benefit of their loved ones, especially grandchildren. They persist in these practices despite the widespread availability of fruit and vegetables on the commercial market, the perception of unprofitability of allotment cultivation and the stereotype that vegetables grown in urban environments are harmful [102].

4.3. FAGs Supply Residents with a Close, Cheap, Self-Created and Accessible Environment and Give Opportunities to Create Bottom-Up Facilities

Based on the statements of allotment holders and experts, the current situation is generally favourable for existing plot holders. However, it offers little hope for potential new gardeners, as the turnover of plots is limited and unrelated to their actual upkeep or use [103]. Although the land itself does not belong to the allotment holder, plots are leased on an indefinite basis and the right of use can be inherited [104]. Allotment holders may use their plots provided they do so in accordance with the designated purpose, comply with the regulations and pay the requisite fees [86]. The plantings, equipment and facilities on the plot, financed by the allotment holder, remain their property [103]. Even symbolic demarcation of garden space fosters community building by strengthening control over the shared space perceived as ‘one’s own’ [105]. Such demarcation also discourages outsiders from entering areas clearly marked as belonging to an organised community.

If an allotment holder falls into arrears with garden fees, they may offset this debt by carrying out work (personally or through a relative) for the benefit of the FAG with the board’s consent [106]. Thus, fees are not necessarily a barrier to plot use, even for less affluent gardeners. Plot cultivation costs, however, vary widely and are determined by individual financial capacity and imagination. In practice, there is also an informal market for plots. In the Warsaw area in 2024, the price of ‘spacing’ (i.e., payment for the transfer of a plot) ranged from PLN 30,000 to PLN 200,000 depending on location and condition of development, particularly the quality of the gazebo or summerhouse. For an average 400–500 m2 plot, the price was approximately PLN 50,000. Respondents emphasised that this high entry threshold contradicts the original purpose of FAGs—to provide recreational space for low-income residents of nearby housing estates.

Proximity to the place of residence emerged as one of the most important benefits of FAGs. In the literature, 500–600 m is often cited as the distance conferring a sense of proximity, assuming one visit per day, whereas with multiple visits the optimal distance is 300–350 m [107]. Shorter distances substantially enhance the possibility of informal social control. The most advantageous FAG locations are therefore near residential developments and visible from upper-floor windows.

FAGs constitute extensive green areas that support the urban ecosystem and benefit gardeners and non-gardeners alike [108]. Yet fulfilling gardeners’ needs may conflict with the wider public’s desire to access these spaces. Debate on opening FAGs to all city residents has persisted for years [88]. At one extreme, some advocate complete liquidation and transfer of the land to urban development; at the other, preservation of gardens as semi-enclosed spaces accessible only to a limited group. Between these positions lie various proposals to increase public access—from limited opening during events to conversion into public parks [109]. Critics of park conversion argue that, due to their plantings and cultivation practices, allotment gardens possess ecological characteristics distinct from those of parks [27].

Gardening itself is cyclical and requires sustained seasonal commitment [110,111]. Even FAG boards acknowledge an erosion of the traditional ‘allotment’ model, with a shift—possibly reversible—from the ‘granny’s garden’ to a ‘daisy and lawn’ model [21]. Gardening knowledge is typically transmitted intergenerationally or exchanged among gardeners. As a result, many possess tacit knowledge—skills difficult to articulate but acquired through hands-on experience and mentor–apprentice relationships [112].

Observations confirm that allotment holders’ knowledge is primarily practice-based. This is both a strength, underpinning successful cultivation, and a limitation, potentially fostering resistance to new horticultural trends. Some researchers have criticised allotment holders for non-ecological practices [113]. Plots are not cultivated collectively by all members of a given FAG, but mutual support is common—watering each other’s crops, lending tools and sharing experience. The intensity of such sharing depends on the specific community dynamics, including informal leadership. Those who use plots mainly for recreation participate less in this exchange than those engaged in productive gardening. In more communal settings, the transfer of services, resources and knowledge is more pronounced, supported by both the physical and symbolic characteristics of shared spaces [114]. Respondents suggested that FAG boards could be supported systemically in fostering community (e.g., by creating shared spaces, integration activities and educational programmes).

Allotment holders may freely manage their crops and are under no obligation to share produce with others; commercial activity on plots is, however, prohibited [103]. The contemporary trend is towards prioritising recreation over cultivation, leading to more lawns and fewer cultivated areas—at its extreme, the ‘daisy and lawn’ model or ‘urban dacha’ with minimal horticultural function. The presence of coniferous plants in only a minority of plots challenges stereotypes about FAG landscaping [27]. This style of use gained popularity during the pandemic. In summary, respondents indicated that food self-production is no longer the primary function of FAGs, in line with the historical tradition of Warsaw’s allotment gardens [88].

4.4. FAGs Create Well-Being in Residential Areas. Beneficial Features of FAGs and Their Facilities on Meeting the Demand in the Scope of Determinants of Residents’ Well-Being

The diverse dimensions of land availability make allotment gardens an attractive, lower-cost alternative for leisure [104]. The multiple benefits derived from FAGs range from physical activity to social interaction, thereby improving the overall well-being of allotment holders. Social ties develop more readily in environments close to home, where residents share common interests and identify with a distinct area.

A particularly notable aspect is the cultivation of unusual or heritage varieties of vegetables and fruit, which increases crop diversity and revives species not grown for decades. Such crops are often low-maintenance and well adapted to local conditions. The opportunity to enhance horticultural competence, practise organic cultivation and popularise extraordinary edible plants also emerged as an important benefit [99]. Consequently, the consumption-related offer of FAGs appears rich, varied and competitive with neighbourhood vegetable shops [104].

The most frequently discussed and controversial issue remains the question of opening FAGs to outsiders. While greater accessibility could expand recreational opportunities within residential areas and foster broader social networking [24,27], it also raises concerns over privacy, security and the preservation of community identity.

5. Conclusions

The analysis confirmed that the features of residential well-being identified in the scientific literature—recreation and leisure, support for physical and mental health, formation of social relationships, and healthy, affordable and distinctive food self-production—are all characteristics of Family Allotment Gardens (FAGs). FAGs effectively address residents’ needs, particularly in terms of socio-recreational and productive functions. Their accessibility promotes their use as an economical and health-enhancing form of recreation, contributing to physical well-being and strengthening social bonds within local communities. Nevertheless, respondents’ attitudes towards social integration varied, indicating an increasing individualisation of allotment use. Overall, FAGs support the satisfaction of all six identified domains of residents’ needs.

Although self-production functions were frequently reported to be in decline, the analysis demonstrated that FAGs still strongly favour food self-production. While the costs of maintaining a plot may undermine its economic profitability, its value is understood in terms of the quality and availability of produce and the acquisition of horticultural skills. In this context, allotments offer a viable alternative to local fruit and vegetable outlets.

Data analysis revealed a relative balance between the number of socio-recreational plots and self-production plots, reflecting the diversity of residents’ needs. Facilities largely support both recreational and productive functions, confirming their multifaceted importance. Many infrastructural elements simultaneously serve both spheres—for example, green spaces enhance aesthetics and comfort for recreation while also providing space for cultivation and safety of use. As a result, FAGs play a complementary role, combining relaxation and food production in ways that allow flexible adaptation to individual preferences. FAGs can thus be regarded as a tool for fostering well-being in residential areas.

The research design proved fit for purpose. Against the backdrop of existing knowledge on FAGs, the qualitative study elicited richer and more detailed insights into the characteristics of FAGs influencing residential well-being. A key limitation is that the sample was confined to Warsaw; future studies should compare results with other European cities and supplement qualitative findings with quantitative research on representative populations.

The study clearly demonstrates the benefits of urban gardening for residents’ well-being and, at the same time, provides evidence to inform contemporary urban policy. One example is the “Adaptation Strategy of the City of Warsaw until 2030” [115], which highlights ‘high adaptability’ in areas such as human health, agriculture, forestry and the urban natural system. The strategy anticipates significant improvements in the quality of life and health protection, as well as enhanced safety and comfort for residents.

Accordingly, the well-being matrix developed in this study (Figure 4)—which identifies strengths and weaknesses in the supply of urban-gardening benefits relative to residents’ needs—can be a valuable tool for urban planning decisions. By making better use of the FAG network already present in the city, public authorities can actively improve residents’ well-being. Yet Warsaw still lacks a coherent policy on allotment gardens. They are typically perceived as private rather than public spaces and managed by their own boards or by the Polish Association of Allotment Gardeners. For reasons of security and privacy, most FAGs remain closed to outsiders, and public debate focuses largely on access for walkers. Moreover, fragmented responsibilities across at least seven municipal offices hinder the development of an integrated urban policy for urban gardening.

For these reasons, research on FAGs and the dissemination of knowledge about their significance in enhancing residents’ well-being are crucial. The research team is confident that the findings presented here provide strong evidence against any displacement of FAGs and will support their continued inclusion in future spatial and strategic planning by the municipal authorities of Warsaw.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and B.J.G.; methodology, M.L., B.J.G. and P.M.; investigation, P.M., A.S., D.D., M.K., M.M. and K.Z.-C.; data curation, M.L., B.J.G., D.D. and K.Z.-C.; writing—original draft, M.L., B.J.G., P.M., A.S., M.R., R.G., D.D., M.K. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, B.J.G., M.L. and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, within the EN-UTC Program that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No 101003758 (agreement with NCN no. UMO-2021/03/Y/HS4/00201). This research was funded in whole or in part by NCN, UMO-2021/03/Y/HS4/00201. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

Institutional Review Board Statement

After consulting with the WULS Research Ethics Committee, ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its anonymity. The survey was conducted in complete agreement with the national and international regulations in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000). The personal information and data of the participants were anonymous according to the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Parliament (GDPR 679/2016). The survey did not require approval by the ethics committee because of the anonymous nature of the survey and the impossibility of tracking sensitive personal data. A brief description of the study and its aim and the declaration of anonymity and confidentiality of data was given to the participants before the start of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting reported results can be found in the Appendix A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The needs of residents in the scope of social-recreational functions in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

Table A1.

The needs of residents in the scope of social-recreational functions in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

| No. | Social-Recreational Functions | Quotes—Translated from Polish to English + (Age Range) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Need for affordable recreation and rest | Especially, since it’s five minutes from home. We can come here by bike in five minutes and play some ball or do anything else. (18–30 y/o) | Need for proximity to the FAG—opportunity for daily relaxation. |

| a2 | It’s a great escape because you’re technically still in the city, but it feels like you’re in the countryside, (...). (18–30 y/o) | Recreation close to home, FAG. | |

| a3 | We were taught to go to the allotment to take a walk, water the plants, (...). (30–40 y/o) | Family tradition of cultivating FAG. | |

| a4 | We wanted lots of fresh air, lots of greenery. We decided to buy a family allotment so that daughters, grandchildren, and grandparents could all come together (...). (60+ seniors) | Need for a private garden space for family and loved ones. | |

| a5 | Grandparents definitely like to rest there. (...) they don’t really feel like taking long trips to the seaside. (18–30 y/o) | Nearby resting place as an alternative for long-distance trips. | |

| b1 | Need to take care of mental and physical well-being | There are plenty of advantages (...) it definitely has a therapeutic, calming, and relaxing effect, making you more aware. (30–40 y/o) | FAG as a therapeutic space allowing for a slower pace of life. |

| b2 | Friends, family, the dog (...) I mostly like lying on a blanket and listening to the birds sing. (18–30 y/o) | FAG providing relaxation and contact with nature. | |

| b3 | I like to mow the lawn, (...) have an occasional barbecue, a deck chair, and good music. The very model of a Polish allotment gardener. (40–50 y/o) | Simple pleasures bring the most joy. | |

| b4 | My in-laws have an allotment in Ochota district, and we regularly go there to have picnics. (40–50 y/o) | A place for regular family gatherings. | |

| b5 | But the main goal is for twenty strangers to meet, talk, do something together, and maybe even become friends. (40–50 y/o) | FAG as a space for social integration through events and joint activities. | |

| c1 | Needs related to social integration, motivation to build social and family bonds, and friendships | A common language, the soil, and the plants just break down all the barriers. Whether you’re eighty, sixty, or twenty-something, it just doesn’t matter. (60+ seniors) | Community and intergenerational integration. |

| c2 | |||

| c3 | It was easy to form them (bonds) because our plots are next to each other, and in times of need, you find true friends. Real people who can help. (40–50 y/o) | Ease of forming bonds, shared goals, and support groups. | |

| c4 | We are friends here, we exchange plants. (...) Young guys also come here and we use this plot together. (40–50 y/o) | Sharing and cooperation s the foundation of FAG | |

| c5 | Everyone helps each other. (...) You’re not alone here. It’s not like everyone has their own plot with a high fence, we have a real community here. (40–50 y/o) | Community support and creation of FAG-based community |

Table A2.

The needs of residents in the scope of self-production functions in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

Table A2.

The needs of residents in the scope of self-production functions in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

| No. | Self-Production Functions | Quotes—Translated from Polish to English + (Age Range) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| d1 | Self- production of healthy food | I know I haven’t used any chemicals on these vegetables and fruits—I know what I’m eating. I like having that awareness and eating healthily. (30–40 y/o) | Awareness of healthy food |

| d2 | Almost entirely natural. We have our own compost. (...) We want to avoid all kinds of chemicals in our fruits and vegetables (...). (30–40 y/o) | Awareness and need for a clean environment | |

| d3 | Everything is natural. Zero chemicals, nothing that could harm my and my children’s healths. (30–40 y/o) | Need to care for family health | |

| e1 | Self- production of affordable food | You’d just brush the dirt off the carrot and eat it or rinse it under a little tap. (...) You didn’t go to the store for carrots—you went to the allotment. (30–40 y/o) | FAG provides access to homegrown vegetables |

| e2 | The prices of fruits and vegetables in Warsaw have become extremely high lately, so we decided that we can save money and enjoy the results of our work, it’s a win-win. (30–40 y/o) | Combining economic and recreational benefits. | |

| e3 | With hard times ahead, here we will have cucumbers, here a bit of onion, carrots, parsnips in a row, and tomatoes over there. (40–50 y/o) | Safety buffer for difficult times | |

| e4 | We need to take a step back—maybe the functions of food production and housing have separated too much, and the urban food system has been pushed out of the city. (40–50 y/o) | Increasing the role of food self-production in the city | |

| f1 | Self-production of extraordinary food | We have a whole vegetable garden to ourselves. We grow our own fresh vegetables at a low cost, and it’s a pleasure to eat something fresh that hasn’t been stored in any warehouse. (30–40 y/o) | Availability of vegetables fresh from the field |

| f2 | (...) I started promoting plants that have been forgotten in our culture. They might not be directly considered edible, but they absolutely are. (...) by doing this, we can diversify our diet and improve our health with various herbs, flowers, and seeds full of great microelements, vitamins, and nutrients. (30–40 y/o) | Possibility of growing rare and forgotten edible plants—expanding the diet and cultivation variety |

Table A3.

The supply of accessibility to FAGs in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

Table A3.

The supply of accessibility to FAGs in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

| No. | Types of Accessibility | Quotes—Translated from Polish to English + (Age Range) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | Land ownership | Well, with plots it’s like this—they are usually private property (...). There’s always an owner, and people who have these plots either lease them or rent them and actually produce some fruits and vegetables there, and nobody else will enter. (30–40 y/o) | Sense of ownership providing feeling of durability and stability |

| a2 | (...) there are lots of people who own plots solely in the hope of getting compensation if something is built on their land in the future (...) so (...) they keep the plot just in case of such compensation (...). (30–40 y/o) | Speculative interest in FAG | |

| b1 | Ownership of crops | I had the opportunity to work on my friends’ plot for a year quite often (...). However, formally, according to the FAG regulations, there’s no provision allowing friends to take care of the plot when the owners can’t. It’s against the rules (30–40 y/o) | Sharing plots with third parties as a grey area |

| c1 | Proximity | For us it’s great, when we retire, we’ll have a barbecue, sit in the garden (...). Especially since it’s only five minutes from home. We can ride a bike here in five minutes (...) Going somewhere outside Warsaw is a whole journey. (30–40 y/o) | Advantage of proximity to home, quick access |

| d1 | Financial accessibility | Only people with money can afford allotments. Or those with the right connections (...). During the pandemic allotments became a luxury commodity. (30–40 y/o) | Allotment gardens as a luxury commodity |

| d2 | (...) people tend to value their work highly because they want to get more money. (...) this is because (...) someone put a lot of effort into the allotment and thinks it’s worth a lot. And market conditions naw are such that there’s a lot of demand, and indeed, these plots are expensive. (30–40 y/o) | Allotment price reflecting the work and investment put into it | |

| d3 | (...) plot prices aren’t regulated; it depends on the price set by the seller—so the city should somehow intervene or at least take an interest in this issue (...) (30–40 y/o) | Lack of FAG price regulation | |

| e1 | Accessibility for outsiders | A major downside is visitors who don’t respect the shared space. They think it’s something everyone has to take care of, but not them. (...) I think an open FAG could function well as a park as well. (40–50 y/o) | Limiting access for outsiders |

| e2 | In my opinion, all existing garden plots within the city should absolutely be preserved as green spaces. However, as spaces balance between public and private—because this, in my opinion, gives them greater legitimacy as public urban spaces. (40–50 y/o) | Private/public status of FAG | |

| e3 | Even two or three plots were designated for communal cultivation (...) Like a program for kids from nearby preschools, where they can plant vegetables and fruits, that kind of thing. (30–40 y/o) | Opportunities for cultivation and interaction for non-FAG members |

Table A4.

Supply of benefits from FAGs in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

Table A4.

Supply of benefits from FAGs in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

| No. | Types of Benefits | Quotes—Translated from Polish to English + (Age Range) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | Health and recreation | Gardening really draws people in. Once you start, it’s hard to stop (...) you return to natural ways of taking care of your body and mind (30–40 y/o) | Enjoyment of working in FAG, passion for gardening |

| a2 | (...) especially during the pandemic, it became a therapeutic space, a safe haven where you could come and spend some time. (30–40 y/o) | FAG as a relaxation space, opportunity for a change of environment | |

| a3 | So those [who cultivated their own plots] didn’t get sick because they ate sourdough bread and homemade pickles (...) they lived in harmony with the environment’s rhythm (...). (30–40 y/o) | Belief in health through return to nature | |

| a4 | A return to the primal human behaviors. Getting dirty, getting tired, feeling satisfaction when something’s watered, a strawberry grows, or a path is laid properly, or something gets painted. (30–40 y/o) | Joy of returning to fundamental activities | |

| a5 | (...) allotment gardens are super important for the city (...) their history is part of the city’s history. [For the users], they are spaces to be free. (30–40 y/o) | Need to ensure freedom of choice in activities | |

| a6 | The whole heritage of being an allotment gardener (...) has many dimensions. First a (...) therapeutic one (...) being in a relaxation space, creating your own harmony, calming down (...). (30–40 y/o) | FAG as spaces of relaxation | |

| a7 | (...) above all it’s a green space (...) on hot summer days it’s clearly cooler there, (...). So (...) it improves the quality of urban life, it’s a positive thing. (30–40 y/o) | Heat island reduction, improving urban comfort | |

| b1 | Enhancing gardening skills | (...) besides the summer season, when we cultivate and meet, we also learn gardening skills from one another. It has, let’s say, this element of horizontal education, where we teach each other (30–40 y/o) | Gardening and social skill-building |

| b2 | With the climate changing to extreme heat, I want to know how to cope. For me the plot is a bit of an experimental field, a learning ground. For some others it is (...) some sort of gardening school (30–40 y/o) | Gaining new adaptive skills | |

| b3 | Allotment gardeners are cautious or hostile towards knowledge they haven’t gained themselves. | Experience and FAG work are highly valued by users | |

| c1 | Building social relations | I think the pandemic made us realize we’re social beings (...) when we’re alone, we don’t function well mentally, and we need to gather around common ideas. This green idea inspires many people. (...) (30–40 y/o) | Community-building, ensuring security through togetherness |

| c2 | (...) some allotment gardens have communal spaces, like a clubhouse for meetings (...) where there is a playground for children, (..) and children from different plots are playing there. These spaces encourage people to spend time together. (30–40 y/o) | Creating communal spaces within FAG strengthens social interactions | |

| c3 | Perhaps better cooperation (...) with municipal services? Because we often called about some vandals entering (...), and we were often ignored by these services. (30–40 y/o) | Issues related to vandalism threats | |

| d1 | Consumption | (...) allotment gardens [can be] a food source for individuals (...) ann additional element of the food system. (40–50 y/o) | FAG as part of the food system |

| d2 | I like the old allotment style (...) 30% vegetables and fruits, 30% shrubs, and 30% recreation. (60+ seniors) | Returning to the roots of utilitarian cultivation | |

| d3 | I think allotments are the largest and the best places for this. There you can really produce some food, and we should prioritize protecting this function. (30–40 y/o) | Haigh value and tradition of food production in FAG |

Table A5.

Supply of equipment in FAGs in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

Table A5.

Supply of equipment in FAGs in statements of stakeholders. Source: own elaboration.

| No. | Types of Equipment | Quotes—Translated from Polish to English + (Age Range) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maintaining order | In my opinion, we need an additional waste container there. (30–40 y/o) | Need for larger waste capacity |

| 2 | And in my opinion it should be like in some other gardens. There they have these green waste containers. People bring the waste and the city cleans it periodically. (30–40 y/o) | Difficulty managing organic waste | |

| 3 | I think [nothing’s] really missing (...) for example there is drinking water available for visitors, and that’s great. (30–40 y/o) | Unlimited access to drinking water | |

| 4 | Previously there were no waste bins here (...). Now they’ve built a large bin shelter, so waste disposal is no longer a problem. (30–40 y/o) | Waste bins as a basic need | |

| 5 | Managing communal spaces | They could use some infrastructure—walking paths, benches (which sometimes are there and sometimes are missing), trash cans (sometimes missing). The lighting is bad. (...) Also there’s no public toilet. (30–40 y/o) | Lack of urban furniture and essential amenities |

| 6 | (...) and for example, based on conversations with allotment gardeners, I came up with something like a tool rental service, so that people wouldn’t have to buy everything themselves, but could borrow equipment and then return it, creating something shared. (30–40 y/o) | Tool sharing system | |

| 7 | It might be nice to create a shared space, like a common room or a clubhouse (...). (40–50 y/o) | Need for communal spaces, e.g., a clubhouse | |

| 8 | (...) The paths are uneven in height, there’s grass and the strollers tip over. For older people, like those with crutches, it can be a problem. There are uneven surfaces (...) some lighting would also be nice, especially if it could support surveillance. (30–40 y/o) | Accessibility issues for all, e.g., lack of lighting | |

| 9 | There are no toilets for people who might want to come for a walk. (30–40 y/o) | Need for public toilets | |

| 10 | [There’s a lack of] bike racks. (30–40 y/o) | Need for bike racks | |

| 11 | It’s generally a requirement to have your own compost bin, but it’s… not enforced. No one checks it. (30–40 y/o) | Need for oversight of recycling requirements |

References

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Bennett, J.; Edwards, R.; Jacobs, D.; Nathan, K.; Ormandy, D. Review of the Impact of Housing Quality on Inequalities in Health and Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 44, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Liao, C. Examining the importance of neighborhood natural, and built environment factors in predicting older adults’ mental well-being: An XGBoost-SHAP approach. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratidis, K. Compact city, urban sprawl, and subjective well-being. Cities 2019, 92, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In Culture and Politics: A Reader; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, W. Where you live does matter: Impact of residents’ place image on their subjective well-being. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maykrantz, A.S.; Kost, E.J.; Neck, C.B.; Houghton, J.D. The relationship between neighborly social capital and health outcomes. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33 (Suppl. S2), ckad160.1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węziak-Białowolska, D. Quality of life in cities—Empirical evidence in comparative European perspective. Cities 2016, 58, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasocki, M.; Majewski, P.; Zinowiec-Cieplik, K.; Szczeblewska, A.; Melon, M.; Dzieduszyński, T.; Grochulska-Salak, M.; Kaczorowska, M.; Derewońko, D.; Gawryszewska, B. Urban garden communities’ social capital as a support for climate change adaptations—A case study of Warsaw. Misc. Geogr. 2025, 29, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfreddo, C.S.; Moreira, C.H.C.; Nicolau, B.; Ortiz, F.R.; Ardenghi, T.M. Socioeconomic inequalities in oral health-related quality of life in adolescents: A cohort study. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 2491–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The New Urban Crisis: Gentrification, Housing Bubbles, Growing Inequality, and What We Can Do About It; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W. The built environment and mental health. J. Urban Health 2003, 80, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkel, E.D.; de Vries, S. Nearby green space and human health: Evaluating accessibility metrics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, A.; Lorenzon, A.; Veitch, J.; Macleod, A.; Sugiyama, T. Is greenery associated with mental health among residents of aged care facilities? A systematic search and narrative review. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Liu, H.; Lu, H. Can Even a Small Amount of Greenery Be Helpful in Reducing Stress? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; van Winsum-Westra, M.; de Vries, S.; van Dillen, S.M. Allotment gardening and health: A comparative survey among allotment gardeners and their neighbors without an allotment. Environ. Health 2010, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soga, M.; Cox, D.T.C.; Yamaura, Y.; Gaston, K.J.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Health Benefits of Urban Allotment Gardening: Improved Physical and Psychological Well-Being and Social Integration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsrud, M.; Goth, U.S.; Skjerve, H. The Impact of Urban Allotment Gardens on Physical and Mental Health in Norway. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y. Architectural Lessons from Environmental Psychology: The Case of Biophilic Architecture. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2007, 11, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, M.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M. Health effects of viewing landscapes—Landscape types in environmental psychology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]