Sustainable Agritourism Heritage as a Response to the Abandonment of Rural Areas: The Case of Buenavista Del Norte (Tenerife)

Abstract

1. Introduction and Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- This research team carried out an analysis of the macroenvironment. This allowed for an exercise in analysing the territorial reality and, with it, the establishment and creation of a list of pre-existing projects.

- (b)

- Interviews with public representatives of the municipality of Buenavista del Norte, to gain knowledge of the projects under development, being executed or planned for the municipality.

- (c)

- A series of interviews with key sources from the different strategic sectors (institutional and private) was also considered, which served as a reference for a better understanding of the proposal’s reality and development and the information gathered from the field trips in situ.

- Semi-structured interviews with public representatives and key informants from strategic sectors (agriculture, tourism, heritage, local government).

- Focus group sessions and participatory dynamics, organised in phases, where participants first worked individually and then collectively to identify resources, projects, and priorities. Tools such as poster boards, post-it notes, and structured group debates were used to stimulate reflection and consensus.

- Direct observation and field visits, carried out by the research team together with local actors, to validate proposals in situ and verify the actual state of resources and infrastructures (see Figure 3).

- Careful selection of key informants based on their representativeness and knowledge of the territory (municipal technicians, private stakeholders, associations, community members).

- Triangulation of information, by cross-checking data obtained from interviews, group dynamics, and field observations.

- Consensus-building exercises, in which proposals were debated and validated collectively, reducing the risk of individual bias.

- Systematic transcription, coding, and categorization of responses, which allowed the information to be organised transparently and in a replicable manner.

- The expertise and diversity of participants, coming from both public and private sectors, including municipal staff and technicians from the Tenerife Island Council (Cabildo).

- The depth of qualitative work, carried out through in-depth interviews and collaborative workshops held between February and April 2023, which provided rich and sufficient information to meet the study’s objectives.

- (1)

- Group dynamics using poster boards, post-its notes and office supplies.

- (2)

- With the technicians of the Municipality of Buenavista del Norte, the focus was on the identification of resources and development opportunities in the municipality with a debate session on the resources and projects that were discussed in parallel. During the debate, all proposals were analysed, and a list of possible projects and associated infrastructure was created.

- (3)

- The group dynamics fostered collaboration and creativity among the team members, allowing for the identification of possible synergies between existing resources and proposed projects.

- (4)

- With the Buenavista del Norte business sector group, the focus was on continuing the dynamics developed with the technical roundtable. The group was divided into two teams and given the specific task of working separately on the identification and creation of proposals for local development. Once each team had completed its task, all ideas were reflected on all participants. During the debate and discussion process, the analysis of the resources and infrastructures of the municipality was worked on, and the projects were discussed in parallel, which allowed the participants to relate some ideas and suggest new ones that could be used to develop future projects in the municipality. Furthermore, the active discussion of the ideas allowed the participants to connect the projects with the possible infrastructures where they could be developed, which allowed them to identify synergies between both and to generate a list of ideas with a comprehensive and collaborative vision.

- (5)

- In the case of the group dynamics developed with key informants from the public sector, four people were involved and divided into two groups of two. Each group was given a specific task: one group was asked to create a list of idle resources or infrastructure in the municipality, while the other was asked to draw up a list of possible projects to be developed in the Municipality. After approximately 20 min of work, each group was asked to write down each idea and/or proposal and make them visible to all participants. The meeting was fruitful, as it allowed for active discussion and collaboration between the team members, which led to the identification of possible synergies between the projects and existing resources in the Municipality.

2.1. Information Processing

- (a)

- Collection and organisation of the information from the sessions: During the process of conducting the sessions, the information derived from the dynamics carried out by the participating group was collected (Table 2).

- (b)

- Transcription, coding and organisation of the information: The information collected was transcribed for later analysis. It was coded into key areas of resources, ideas and projects. The information was organised considering the responses related to the specified tasks.

- (c)

- Analysis and interpretation: Based on the information obtained from the interviewees, a process of analysis and interpretation of the resources, ideas and projects was established to identify similarities, and characterisation of common problems, as well as to focus on the more proactive part of seeking and identifying the potential of the projects in line with the overall view of the group.

- (d)

- Feasibility presentation: In this phase, the main projects derived from the previous phase were identified as the highest priorities from an economic and social point of view for the municipality.

- (e)

- Contrasting information and territorial viability: This process focused on contrasting the information collected with the subsequent territorial analysis within the municipality, through specific field trips and personal interviews with different people who could not participate in the aforementioned sessions.

2.2. Analysis Phase-Field Trips for the Diagnosis of the Resources and Infrastructures of the Municipality

3. Results

3.1. Rural Development Positions

3.2. Response Through Local Participation to the Demographic Challenge Characterised by the Unique Nature of a Fragmented Territory

- (a)

- Community Response: Wine Tourism as a Means of Recovering Agricultural Landscapes and Fostering Economic Sustainability

- (b)

- Community Response: Revitalisation of Local Cheesemaking to Preserve Traditional Livestock Farming and Boost Tourism

- (c)

- Community Response: Opportunities in Agri-food Spaces

4. Discussion

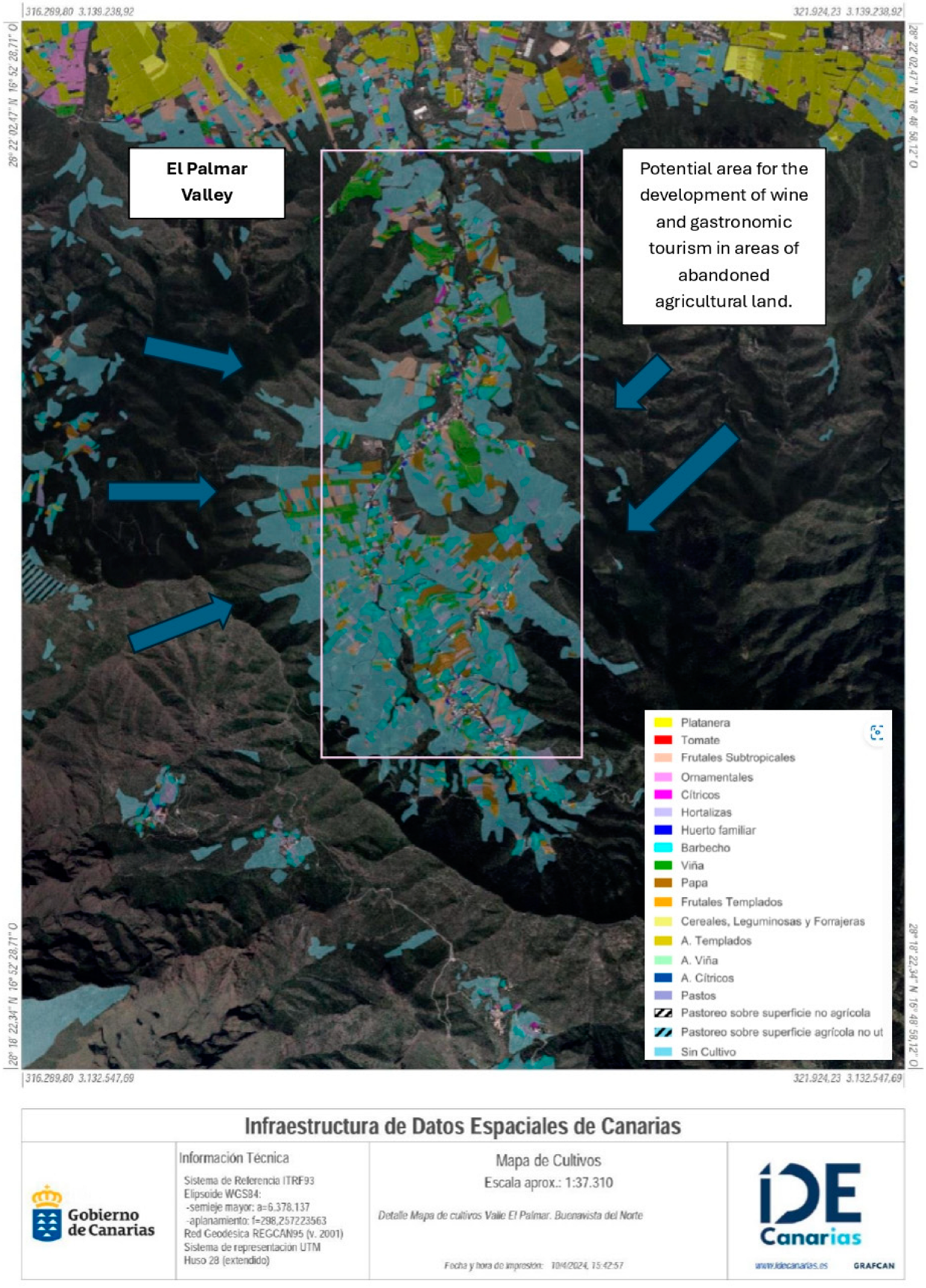

- Regenerating the landscape and recovering uncultivated areas.

- Distinguishing the municipality through a unique viticulture product, as no active wineries currently exist under the DO.

- Establishing a strategic tourist attraction for the municipality, given that the road through Valle de El Palmar serves as a critical route (north–south corridor) for vehicles travelling between Buenavista del Norte and the popular Valle de Masca/Santiago del Teide area, one of Tenerife’s most recognised tourist destinations.

- Creating jobs and opportunities for the region’s youth.

- Encouraging entrepreneurship in activities related to winery operations (e.g., distribution, marketing, specialised shops, wine bars, guides, tourist intermediaries, wine clubs).

- Supporting the circular and local economy, enabling restaurants in the valley to offer zero-kilometre products.

- 1.

- Non-formal education and training to prevent the complete disappearance of the sector

- 2.

- Local institutional support for the recovery of abandoned cheesemaking facilities

Public Institutions Participation in the Face of the Demographic Challenge

- Rescue of ethnographic uses and traditions of Manuel Lorenzo Perera.

- Advice for entrepreneurs and companies

- The Project: archaeological diagnosis, archaeoethnographic park. carried out by the company PRORED SOC. COOP. since May 2023 around ‘Salto del Aljube’ on the archaeological potential of the ravine within the project of repopulation and activation of the Valley of El Palmar.

- The adaptation of playgrounds in Valle de El Palmar.

- Development of the OROBAL programme through economic funds from Next Generation aimed at supporting women in rural and urban areas and which has had participation in the municipality with the training of unemployed women including advice on sustainable rural tourism.

- The holding of several editions of the Mesas con Salitre gastronomic fair as a space for training and development of the gastronomic fabric of the municipality based on the enhancement of local produce with training sessions for professionals in the catering sector in the Municipality, show-cooking, tastings, combining music and gastronomy.

- Development of online courses on entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector and training for the hotel and catering sector in the Municipality.

- Development of Traditions Day with the potato harvest in the neighbourhood of Las Portelas.

- Celebration of the first edition of “Puebleando Buenavista” (2024) as an activity within the repopulation and activation project for El Valle de El Palmar, featuring various routes and tastings of local products from businesses in the region to promote the development of the circular economy.

5. Conclusions

6. Future Research and Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Navarro-Valverde, F.; Cejudo-García, E.; Cañete-Pérez, J.A. The Lack of Attention Given by Neoendogenous Rural Development Practice to Areas Highly Affected by Depopulation. The Case of Andalusia (Spain) in the 2015--2020 Period. Eur. Countrys. 2021, 13, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraja, E.; Herrero, D.; Martínez, M. Política Agraria Común y despoblación en los territorios de la España interior (Castilla y León). AGER Rev. Estud. Sobre Despoblación Desarro. Rural. (J. Depopulation Rural. Dev. Stud.) 2021, 2021, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello Paredes, S.A. La despoblación en España: Balance de las políticas públicas implantadas y propuestas de futuro. Rev. De Estud. De La Adm. Local Y Autonómica 2023, 2023, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefănescu, M.S.; Colesca, S.E.; Păceşilă, M.; Precup, I.M.; Hărătău, T. Sustainability of Local and Rural Development: Challenges of Extremely Deprived Communities. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence. Buchar. Univ. Econ. Stud. 2023, 17, 1628–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercher, N. The Role of Actors in Social Innovation in Rural Areas. Land 2022, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, V.; Sáez, L.A. La despoblación rural en España. Características, causas e implicaciones para las políticas públicas. Presup. Y Gasto Público 2021, 102, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Laaser, U. Population ageing from 1950 to 2010 in seventeen transitional countries in the wider region of South Eastern Europe. South East. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosta, P.; Szukalski, P.; Czibere, I.; Kovách, I. Depopulation and Public Policies in Rural Central Europe. The Hungarian and Polish Cases. Ager 2021, 33, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.G.; Baltas, P. Rural Depopulation in Greece: Trends, Processes, and Interpretations. Geographies 2024, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntele, I.; Istrate, M.; Horea-Șerban, R.I.; Banica, A. Demographic Resilience in the Rural Area of Romania. A Statistical-Territorial Approach of the Last Hundred Years. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, I. Assessing the problem of affordable housing in Greece. Discov. Cities 2024, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryzhevska, Y.; Karácsonyi, D. Rural population in Ukraine: Assessing reality, looking for revitalization. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2012, 61, 49–78. Available online: https://ojs3.mtak.hu/index.php/hungeobull/article/view/2991 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Rizzo, A. Declining, transition and slow rural territories in southern Italy: Characterizing the intra-rural divides. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 24, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdzińska, A. Depopulation and population ageing in Europe in the 2010s: A regional approach. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2024, 31, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickovic, B.; Mijanovic, D.; Spalevic, V.; Skataric, G.; Dudic, B. Contribution to the Analysis of Depopulation in Rural Areas of the Balkans: Case Study of the Municipality of Niksic, Montenegro. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M.; Zapletalová, J.; Nováková, E. Is the European countryside depopulating? Case study Moravia. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 80, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancsóné, Z.; Kupi, M.; Happ, E. The role of tourism management for sustainable tourism development in nature reserves in Hungary. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2023, 49, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borović, S.; Stojanović, K.; Cvijanović, D. The future of rural tourism in the Republic of Serbia. Ekon. Poljopr. 2022, 69, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A. How has rural tourism influenced the sustainable development of traditional villages? A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F.; Martellozzo, F. Is Rural Tourism-Induced Built-up Growth a Threat for the Sustainability of Rural Areas? The Case Study of Tuscany. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltean, R.-C.; Dahlman, C.T.; Arion, F.-H. Visualizing a Sustainable Future in Rural Romania: Agrotourism and Vernacular Architecture. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasteva, N.; Alexova, D. Marketing for rural tourism—strategy and realisation in Bulgaria. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 30, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, G.; Cavallo, A. Rural Identity, Authenticity, and Sustainability in Italian Inner Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pripoaie, R.; Turtureanu, A.-G.; Schin, G.-C.; Matic, A.-E.; Crețu, C.-M.; Pătrașcu, C.-G.; Sîrbu, C.-G.; Marinescu, E.Ș. The Contribution of Tourism to the Development of Central and Eastern European Countries in the New Post-Endemic and Geostrategic Context. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Ouyang, B.; Quayson, M. Navigating the Nexus between Rural Revitalization and Sustainable Development: A Bibliometric Analyses of Current Status, Progress, and Prospects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živanović, V.; Joksimović, M.; Golić, R.; Malinić, V.; Krstić, F.; Sedlak, M.; Kovjanić, A. Depopulated and Abandoned Areas in Serbia in the 21st Century—From a Local to a National Problem. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, Ł. Digitalisation as a Challenge for Smart Villages: The Case of Poland. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collantes, F.; Pinilla, V.; Sáez, L.A.; Silvestre, J. Reducing Depopulation in Rural Spain: The Impact of Immigration. Popul. Space Place 2014, 20, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, A.; Felsenstein, D. Support for rural tourism: Does it make a difference? Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyara, G.; Jones, E. Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E.; Hernández, M.; Coca, A.; Cantero, P.; Del Campo, A. Turismo comunitario en Ecuador: Comprendiendo el community-based tourism desde la comunidad. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2008, 6, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Feria, R.; Hernández-Ramírez, M.; Ruiz-Ballesteros, E. Depopulation, community-based tourism, and community resilience in southwest Spain. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 88, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funduk, M.; Biondić, I.; Simonić, A.L. Revitalizing Rural Tourism: A Croatian Case Study in Sustainable Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable Development and Rural Tourism in Depopulated Areas. Land 2021, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz Val, P.; Puche Regaliza, J.C.; Antón Maraña, P.; Aparicio Castillo, S. Factores determinantes para la satisfacción del turista en destinos de interior: Impacto sobre el problema de la despoblación. Investig. Turísticas 2024, 27, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, S.; Hunter, C.; Blackstock, K. A typology for defining agri-tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, A.; Barbieri, C.; Rozier Rich, S. Defining agritourism. A comparative study of Stakeholders. Perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Xu, X.; Gil-Arroyo, C.; Rich, S.R. Agritourism, Farm Visit, or... ? A Branding Assessment for Recreation Farms. J. Travel Res. 2015, 55, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A. Cultural and touristic aspects of Gamalost, a local cheese from the Fjord of Norway. J. Gastron. Tour. 2019, 3, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, M.D.L.; da Cunha, J.A.C.; Passador, J.L. Gastronomic tourism and regional development: A study based on the minas artisanal cheese of Serro. Cad. Virtual De Tur. 2018, 18, 168–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ermolaev, V.A.; Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A. Cheese as a tourism resource in Russia: The first report and relevance to sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrande-Moreau, A.; Courvoisier, F.H.; Bocquet, A.M. Le nouvel agritourisme intégré, une ttendance du ttourisme durable. Téoros—Rev. De Rech. En Tour. 2017, 36, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Matzanke, A.; Vidal-González, P. Hiking accommodation provision in the mountain areas of Valencia Region, Spain: A tool for combating the depopulation of rural areas. J. Sport Tour. 2022, 26, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declaración del Cork 2.0. Una Vida Mejor en el Medio Rural; Oficina de Publicaciones de la Unión Europea: Luxembourg, 2016; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/enrd/sites/default/files/cork-declaration_es.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Promotour. Informe Sobre Perfil del Turista, Canarias e Islas. 2023. Available online: https://www.turismodeislascanarias.com (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Dorta Rodriguez, A.; Quintela, J.A. The Potential of Wine Tourism in the Innovation Processes of Tourism Experiences in the Canary Islands—An Approach to the Case of the Canary Brand. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de Canarias. Sistema de Información Territorial de Canarias. 2025. Available online: https://visor.grafcan.es (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Informe Sobre los Proyectos Para la Reactivación Socioeconómica y la Lucha Contra la Despoblación—Convocatoria 2022. Ministerio Para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Gobierno de España. 2023. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/reto-demografico/formacion/INFORME%20FINAL%20DE%20SINTESIS%20SOBRE%20CONVOCATORIA%20DE%20SUBVENCIONES%202022.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Rivera Escribano, M.J. Migración prorrural a áreas remotas en tiempo de crisis. Recer. Rev. De Pensam. I Anàlisi 2023, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E.; Gálvez-García, C.; Jaraíz-Arroyo, G. Community-based tourism and rural demographic decline: Reflections from Extremadura (Spain). Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 28, 2329–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapley, T. Sampling strategies in qualitative research. SAGE Handb. Qual. Data Anal. 2014, 4, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Carrasco Pleite, F.; Colino Sueiras, J. Rural Depopulation in Spain: A Delphi Analysis on the Need for the Reorientation of Public Policies. Agriculture 2024, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R.; Christmann, G.B. On the role of key players in rural social innovation processes. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 99, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías Hernández, A.M. El paisaje vitícola de Canarias. Cinco siglos de historia. Ería 2005, 68, 351–364. Available online: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/RCG/article/view/1525 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Fusté Forné, F. El queso como recurso turístico para el desarrollo regional: La Vall de Boí como caso de estudio. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2015, 14, 243–251. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/881/88143642017/html/ (accessed on 18 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- PFAE. 2024. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/good-practices/pfae-plan-de-formacion-en-alternancia-con-el-empleo (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Fusté-Forné, F. Developing cheese tourism: A local-based perspective from Valle de Roncal (Navarra, Spain). J. Ethn. Food 2020, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A.; Wang, R.; Jiang, K.; Yu, H. The Lost View: Villager-Centered Scale Development and Validation Due to Rural Tourism for Traditional Villages in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, T.; Fürnkranz-Prskawetz, A. Demographic change in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Trends, determinants and challenges. In 30 Years of Transition in Europe; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 196–222. [Google Scholar]

| Participatory Dynamics | Explanation | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1. Diagnosis | ||

| Participatory Dynamics 1 | Separated into 2 groups, individually (10 min) and in a group session (30 min). | Think about proposals on the assigned theme |

| Participatory Dynamics 2 | Once they have been presented, the other group has time to complement the proposals presented. | Share the contributions of each group. |

| Phase 2. Good practices in the sector that respect the environment | ||

| Participatory Dynamics 3 | Split into groups, exchanging the themes. | Select the 10 most important resources from each one. |

| Phase 3. Set of personalised recommendations on actions to improve sustainability | ||

| Conclusion | Sharing session | Share the 10 proposals selected by each group. |

| Sector | Area | Agency/Entity |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Informants (Buenavista del Norte Town) | Technician Employment and Local Development Agency AEDL (3) | Buenavista del Norte Town |

| Culture and Events | ||

| Tourism | ||

| Sports | ||

| Technical Office | ||

| Strategic Interest Informants (Private Sector) | Manager | Birding Canarias S.L.U |

| Farmer | Ecological farm ‘La Econtenta’. | |

| Oficial Tourist Guide | Autonomous. Buenavista del Norte | |

| Coordinator/Animator | Canary Islands Agency for Research, Innovation and the Information Society. Fundación Empresa University of La Laguna | |

| Technician | Territorial and Environmental Management and Planning, S.A. | |

| Manager | El Cardon Educación Ambiental S.L. | |

| Professor/Technician/Geographer | Government of the Canary Islands | |

| Archaeologist | PRORED, Soc. Coop. | |

| Strategic Interest Informants (Public Sector) | Technician | Teno Rural Park Management Office. Cabildo of Tenerife |

| Codirector | Chair of management and cultural policies of the ULL-FECAM. | |

| Assistant Direction | Product Department. Tourism of Tenerife. | |

| Agent | Council of Tenerife |

| Places | Activities | Aim |

|---|---|---|

| Town Centre of the Municipality | To observe the different buildings and underused infrastructures, such as the buildings annexed to the Granary, Teleclub, Casa de D. Nicolás, Antiguo Convento de San Francisco, Casa Comunal de los Vecinos de Teno Alto. | To highlight their capacity as versatile spaces for the development of business activities and actions related to the ecotourism sector, culture, tradition and history. |

| Triana Ravine | The observation of this unique space in the municipality was taken into account for its possible revitalisation, dynamisation and use. | The aim is to turn it into a recreational space for the community, tourists and visitors, as well as a useful place to carry out sustainable activities and experiences safely and attractively and to generate new business niches in the area through the improvement of the local footpath, agrotourism or the training of young people in the field of urban gardens. |

| Realisation of the local footpath from the town centre to the Hacienda del Conde Meliá Collection Golf & Spa | The research team’s interest in improving, modernising, and conditioning this space is highlighted. | |

| Coastal stretch of the Golf Course, Los Barqueros—Las Arenas—El Fraile | The visit aimed to improve the stretch and its key points, as well as the creation of new spaces for enjoyment, which would allow new economic activities to be generated at a local level. It is committed to a local development and employment approach that takes into account sustainability and environmental protection. In this way, the aim is to achieve economic growth that is respectful of nature and beneficial for the community and the local development of the Municipality. | |

| Punta de Teno | This visit aimed to implement a series of actions to revalue the Punta de Teno area, making the most of existing spaces to improve their use and creating new spaces and ecotourism products. To this end, the project visited areas such as the Monja viewpoint, the greenhouse and farming area, the old hermitage, and the surrounding area of Ballenita Beach, car parks and the lighthouse. These initiatives seek to catalyse innovative projects in the area and encourage economic development, always from an ecological and environmentally friendly perspective. The aim is to promote a green economy in the region, in line with its cultural and territorial characteristics, thus avoiding any negative impact on the environment. | |

| Valle El Palmar and Complejo Agroalimentario de los Pedregales | The objective of this visit was to directly observe the potential of the valley for the development of activities and actions related to the agro-astro-tourism sector, considering the progressive abandonment of the cultivated area. The potential of the existing agri-food complex and the underutilization of most of its spaces were identified in this hamlet. | |

| Teno Alto | The visit was aimed at revitalising the local economy through the Km 0 gastronomic product in the hamlet of Teno Alto where it can be achieved by revitalising livestock farming through its cheese dairies, highlighting the value of the cheese production process and allowing visitors to connect with it sustainably. | |

| Farmhouses of Masca, Portelas-Bolico and Carrizales | By providing an authentic rural gastronomic experience, visitors will be able to learn first-hand how cheese is produced and enjoy the final product in its original environment. |

| Theme | Key Proposals |

|---|---|

| Enhancement of the Primary Sector | Promote local products and consumption—Develop a local product agenda—Recover agricultural areas (e.g., Valle del Palmar, Los Carrizales)—Focus on vineyards, potatoes, cereals, onions |

| Agricultural Estates & Winery Development | Create a visitable, traditional banana plantation—Support organic coastal farming—Revive wine production in El Palmar Valley |

| Wine/Gastro—tourism Innovation | Develop digital platform linking restaurants by specialty—Educate consumers on local food systems |

| Traditional Trades & Heritage | Restore buildings linked to traditional trades—Create interactive public spaces in historic centre |

| Focus Area | Identified Challenges | Proposed Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Vineyards and Wine Tourism | Abandonment of vineyards—Low profitability-Youth migration | Strategic plan to recover vineyards—Develop wine tourism to boost economy |

| Local Cheesemaking (Teno Alto) | Ageing producers—No generational renewal-Few active cheesemakers | Preserve traditional livestock farming—Promote cheese tourism |

| Agri-food Spaces (Barranco de Triana) | Limited engagement with agri-food education—Underused spaces | Develop spaces for farming, composting, and training—Create rental/lease model |

| Project | Objective | Context | Funding (€) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composta Buenavista | To provide the municipality with a composting plant and the necessary machinery to transform organic waste into high quality worm compost and improve the quality of the municipality’s agricultural soils. | Plan de Apoyo a la implementación de la normativa de residuos y al fomento de la economía circular” comprendida en el Componente 12 “Política Industrial España 2030” del Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia (PRTR), financiado por la Unión Europea–NextGenerationEU (Línea 2) | 248,790.50 € (IGIC included), 90% of which is co-financed by the European Union through the Next Generation EU funds, and the rest, some 24,879.05 €, by the Buenavista del Norte Town Council itself. |

| Buenavista Recupera | To provide the municipality with the necessary material for the collection of this waste from both the general population and large generators, including both containers and the selective collection lorry. It also includes a line of information, dissemination and awareness-raising for both the general public and large generators. In this way, the correct treatment of municipal organic waste is ensured. | Medidas de apoyo para proyectos de construcción, adaptación y mejora de instalaciones específicas para el tratamiento de los biorresiduos recogidos separadamente, dentro del “Plan de Apoyo a la implementación de la normativa de residuos y al fomento de la economía circular” comprendida en el Componente 12 “Política Industrial España 2030” del Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia (PRTR), financiado por la Unión Europea– NextGenerationEU (Línea 1) | 84,092.85 (IGIC included), 90% of which will be co-financed by the European Union through the Next Generation EU funds, and the rest by the Buenavista del Norte Town Council itself, some 8409.28 euros. |

| Rehabilitation of municipally owned housing | The so-called civil servants’ dwellings are three blocks of four dwellings each, which were built in the 1980s to house civil servants and their families who had to travel to Buenavista to provide their services. Over the years, they have lost this main function and have been used for social housing, although they have never had a proper maintenance plan. This grant will allow for the refurbishment of one of the blocks and its use as social rental housing. | Programa para Combatir la Despoblación en el medio rural del Instituto Canario de la Vivienda | 149,000 € |

| Repopulation and activation of Valle de El Palmar, Buenavista del Norte. | Project within the area of ‘Structures for coordination and promotion of entrepreneurship’. | Projects for socio-economic reactivation and the fight against depopulation—Call 2022. Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge | 148,872 € |

| Creation of the Museo de Las Libreas de El Palmar | Convention between the Cabildo and Ayuntamiento de Buenavista del Norte for the creation of Museo de Las Libreas de El Palmar. | Not available Pending implementation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorta Rodríguez, A.; Quintela, J.A.; Albuquerque, H. Sustainable Agritourism Heritage as a Response to the Abandonment of Rural Areas: The Case of Buenavista Del Norte (Tenerife). Sustainability 2025, 17, 8605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198605

Dorta Rodríguez A, Quintela JA, Albuquerque H. Sustainable Agritourism Heritage as a Response to the Abandonment of Rural Areas: The Case of Buenavista Del Norte (Tenerife). Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198605

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorta Rodríguez, Agustín, Joana A. Quintela, and Helena Albuquerque. 2025. "Sustainable Agritourism Heritage as a Response to the Abandonment of Rural Areas: The Case of Buenavista Del Norte (Tenerife)" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198605

APA StyleDorta Rodríguez, A., Quintela, J. A., & Albuquerque, H. (2025). Sustainable Agritourism Heritage as a Response to the Abandonment of Rural Areas: The Case of Buenavista Del Norte (Tenerife). Sustainability, 17(19), 8605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198605