The Social Image of Inland Angling in Poland Within the Concept of Sustainability: A Factual and Stereotypical Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review on Angling as a Source of Stereotypes

1.2. Research Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Design of the Survey

2.2. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

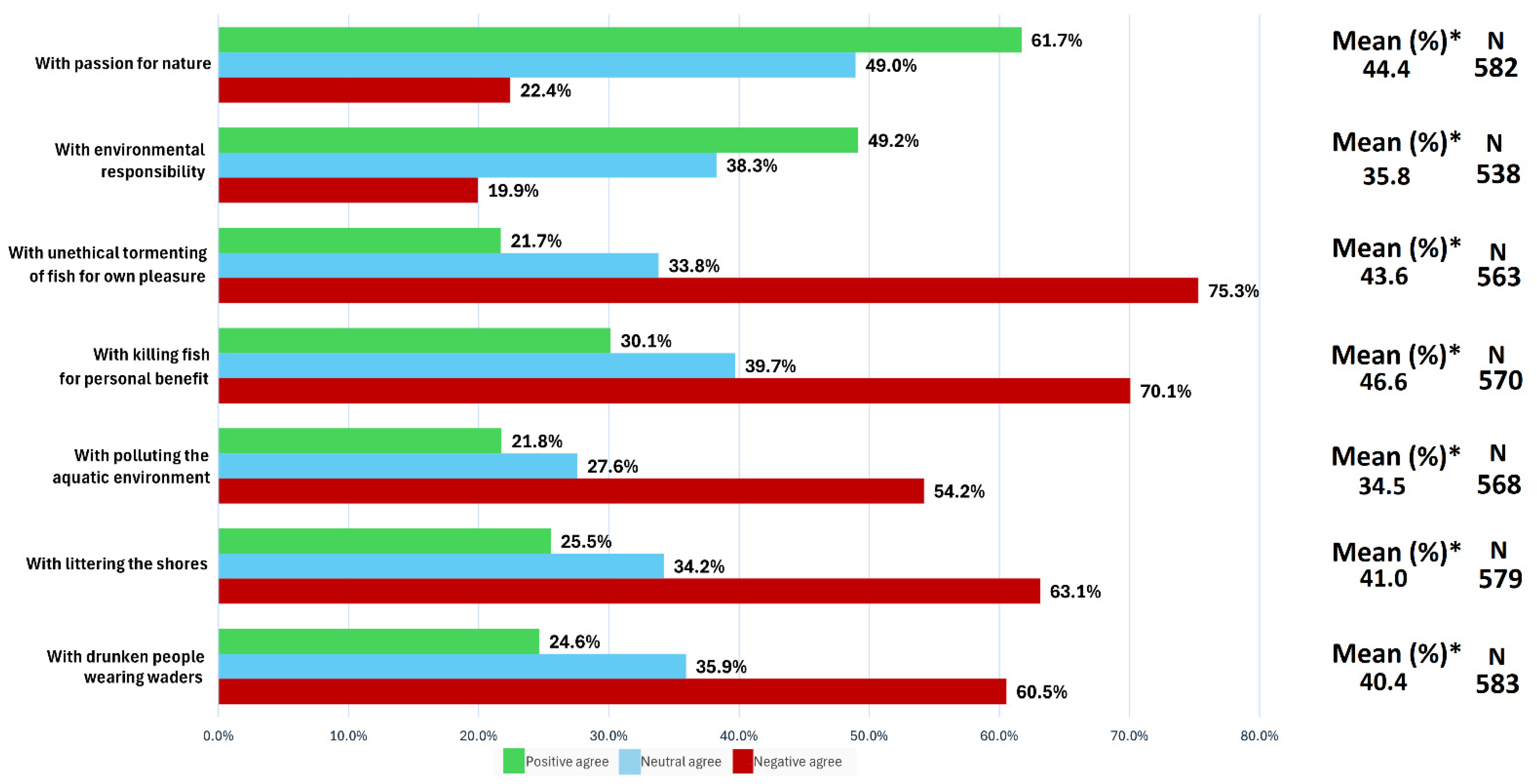

3.1. The Strength of Stereotypes and Associations Depending on Opinions About Anglers

3.2. Verification of Stereotypes and Associations About Angling and Anglers

3.2.1. Angling Versus Other Leisure Activities on the Water

3.2.2. Angling as a Time-Consuming and Costly Hobby Practised in Solitude

3.2.3. Angling as a Pursuit of Big Fish and Sporting Competition

3.2.4. Non-Anglers’ Perceptions of Provisioning

3.2.5. Angling as an Opportunity to Spend Time with Family and Friends

3.2.6. Angling as Unethical Tormenting of Fish for Own Pleasure

3.2.7. Angling as a Passion for Nature

3.2.8. Public Perceptions of Angling in the Context of Associations and Stereotypical Beliefs

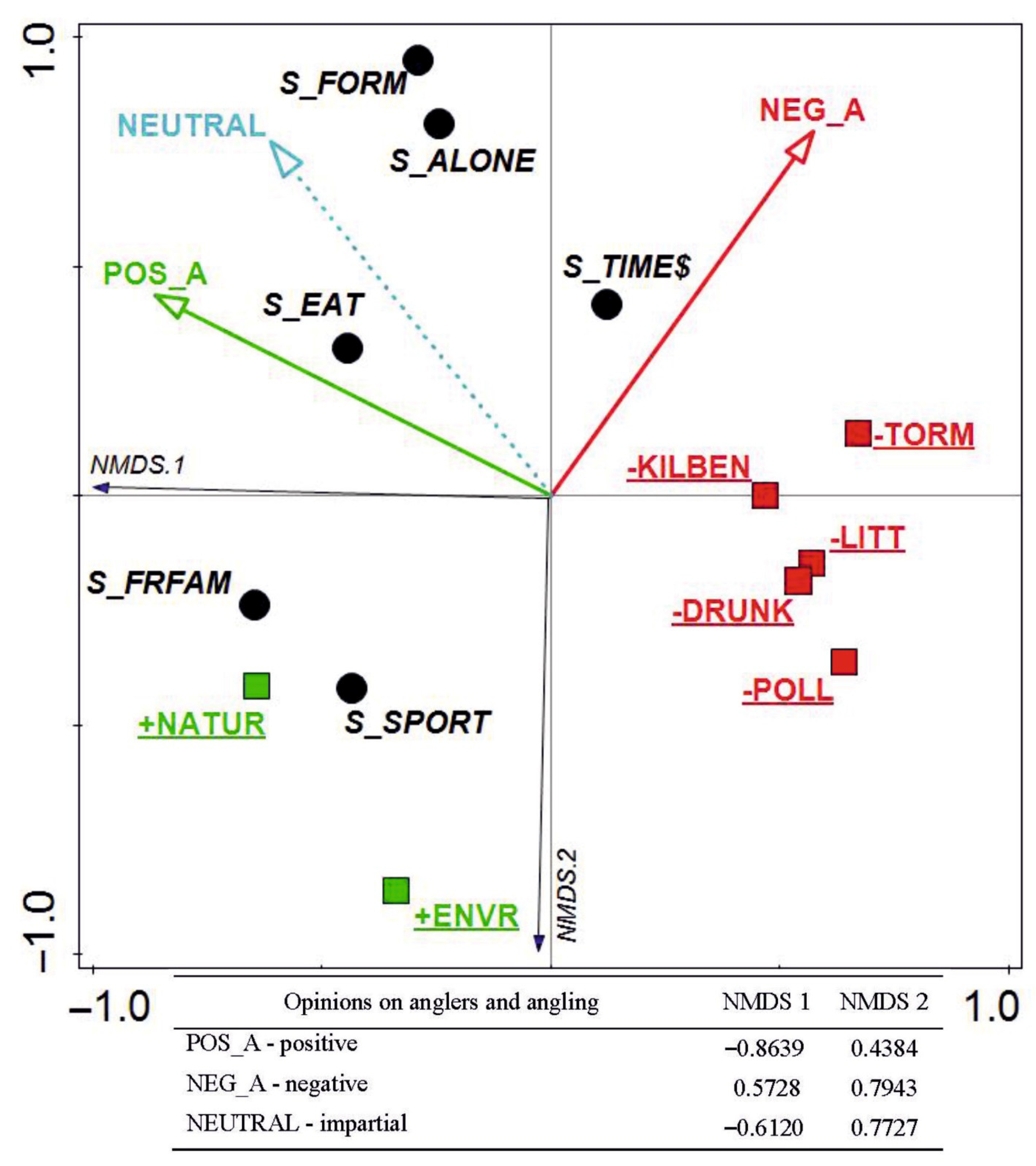

3.3. Factors Shaping Positive and Negative Opinions About Anglers

4. Discussion

4.1. Sustainable Development-Related Stereotypes and Associations About Fishing

4.2. Main Determinants of Associations and Stereotypes About Angling

5. Conclusions and Managerial Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. The Hidden Harvest, the Global Contribution of Capture Fisheries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/11873 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Organa, A. The role of recreational fisheries in the sustainable management of marine resources. In Globefish Highlights a Quarterly Update on World Seafood Markets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Tillner, R.; Bork, M. Explaining participation rates in recreational fishing across industrialised countries. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2015, 22, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołos, A.; Kapusta, A.; Mickiewicz, M.; Czerwiński, T. Aktualne problemy gospodarki rybacko-wędkarskiej i wędkarskiej w pytaniach i odpowiedziach [Current problems of fishing and angling management in questions and answers]. Komun. Rybackie 2016, 3, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Demographic Yearbook of Poland 2024; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Uczestnictwo Polaków w Sporcie i Rekreacji Ruchowej w 2012 r. 2013. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/kultura-turystyka-sport/sport/uczestnictwo-polakow-w-sporcie-i-rekreacji-ruchowej-w-2012-r-,5,1.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Cooke, S.J.; Cowx, I.G. The role of recreational fisheries in global fish crises. Bioscience 2004, 54, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M.B. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.1 and Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure. 2018. Available online: http://cices.eu/content/uploads/sites/8/2018/01/Guidance-V51-01012018.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Karpiński, E.A. Angling in cultural and provisioning ecosystem services. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2022, 37, 407–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, J.; Herr, A. Hunting and fishing tourism. In Wildlife Tourism: Impacts, Management and Planning; Higginbottom, K., Ed.; Common Ground Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Recreational hunting: Ethics, experiences and commoditization. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2014, 39, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, T.J.; Hollingworth, C.E. Fishing for fun: Where’s the catch. In Recreational Fisheries: Ecological, Economic and Social Evaluation; Pitcher, T.J., Hollingworth, C.E., Eds.; Blackwell Science: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordue, T. Angling in modernity: A tour through society, nature and embodied passion. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policansky, D. Catch-and-release recreational fishing: A historical perspective. In Recreational Fisheries: Ecological, Economic and Social Evaluation; Pitcher, T.J., Hollingworth, C.E., Eds.; Blackwell Science: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawak, J. Traktat o Wędkarstwie; Pieśniak, M., Ed.; Red Tag sp. z o.o.: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, H. Leisure value systems and recreational specialization: The case of trout fishermen. J. Leis. Res. 1977, 9, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Cooke, S.J.; Lyman, J.; Policansky, D.; Schwab, A.; Suski, C.; Sutton, S.G.; Thorstad, E.B. Understanding the complexity of catch-and-release in recreational fishing: An integrative synthesis of global knowledge from historical, ethical, social, and biological perspectives. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2007, 15, 75–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Alós, J.; Beardmore, B.; Daedlow, K.; Dorow, M.; Fujitani, M.; Hühn, D.; Haider, W.; Hunt, L.M.; Johnson, B.M.; et al. Understanding and managing freshwater recreational fisheries as complex adaptive social-ecological systems. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2017, 25, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panelli, R. More-than-human social geographies: Posthuman and other possibilities. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 34, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordue, T.; Wilson, S. More-than-human encounters with fish in the City: From careful angling practice to deadly indifference. Leis. Stud. 2022, 42, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, W.-C.; Arlinghaus, R.; Mehner, T. Documented and potential biological impacts of recreational fishing: Insights for management and conservation. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2006, 14, 305–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, S. Indirect consequences of recreational fishing in freshwater ecosystems: An exploration from an Australian perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmach, H. Wizerunek mężczyzny w nazwach wódek [The image of man in vodka brand names]. Probl. Nauk. Stosow. 2018, 8, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, A.; Bohnsack, J.A. A review of catch-and-release angling mortality with implications for no-take reserves. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2005, 15, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.D.; Arlinghaus, R.; Cooke, S.J.; Diggles, B.K.; Sawynok, W.; Stevens, E.D.; Wynne, C.D. Can fish really feel pain? Fish Fish. 2014, 15, 97–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownscombe, J.W.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Chapman, J.M.; Gutowsky, L.F.; Cooke, S.J. Best practices for catch-and-release recreational fisheries–Angling tools and tactics. Fish. Res. 2017, 186, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Driver, B.L.; Tarrant, M.A. Measuring leisure motivation: A metaanalysis of the recreation experience preference scales. J. Leis. Res. 1996, 28, 188–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, H.L.; Gerard, P.D. Temporal changes in fishing motivation among fishing club anglers in the United States. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2004, 11, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardmore, B.; Haider, W.; Hunt, L.M.; Arlinghaus, R. The importance of trip context for determining primary angler motivations: Are more specialized anglers more catch-oriented than previously believed? N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2011, 31, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, A.R.; Karpiński, E.A. New insight into the motivations of anglers and fish release practices in view of the invasiveness of angling. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, T. Mental health benefits of outdoor recreation. In Social Benefits of Outdoor Recreation; Kelly, J.R., Ed.; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Champaign, IL, USA, 1981; pp. 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Midway, S.R.; Lynch, A.J.; Peoples, B.K.; Dance, M.; Caffey, R. COVID-19 influences on US recreational angler behavior. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpiński, E.A.; Skrzypczak, A.R. The significance of angling in stress reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic—Environmental and socio-economic implications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, C.O.; Ditton, R.B. Using recreation specialization to understand conservation support. J. Leis. Res. 2008, 40, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.L. One haunted river: Histories and Spectres of the Odra. Shima 2025, 19, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickley, P. Recreational fisheries—Social economic and management aspects. In Fisheries, Sustainability and Development; Wramner, P., Ackefors, H., Cullberg, M., Eds.; Royal Swedish Academy of Agriculture and Forestry: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009; pp. 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Tufts, B.L.; Holden, J.; DeMille, M. Benefits arising from sustainable use of North America’s fishery resources. Economic and conservation impacts of recreational angling. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 72, 850–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarkowski, T.K.; Wołos, A.; Kapusta, A. Socio-economic portrait of Polish anglers: Implications for recreational fisheries management in freshwater bodies. Aquat. Living Resour. 2021, 34, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W.; Clark, K.; Pettigrew, T. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Glick, P.; Rudman, L.A. (Eds.) On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years After Allport; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhesi, J. Made to Stick? A Cognition and Culture Account of Social Group Stereotypes. Ph.D.; Thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kundra, Z.; Sinclair, L. Motivated reasoning with stereotypes: Activation, application, and inhibition. Psychol. Inq. 1999, 10, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, E.D.; Hox, J.; Dillman, D. International Handbook of Survey Methodology; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariadna. Badania CAWI [CAWI Research]. 2025. Available online: http://panelariadna.pl/wiedza/badania-cawi (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Limesurvey. A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding Margin of Error. 2024. Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org/blog/tutorials/a-comprehensive-guide-to-understanding-margin-of-error (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ter Braak, C.J.F.; Šmilauer, P. Canoco Reference Manual and User’s Guide: Software for Ordination (Version 5.10); Microcomputer Power: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, A.D. An Overview of the Social Norms Approach; W: Changing the culture of college drinking. A socially situated health communication campaign; Lederman, L., Stewart, L., Goodhart, F., Laitman, L., Eds.; Hampton Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery, E.L.; Voelker, C.C.; Nussenbaum, B.; Rich, J.T.; Paniello, R.C.; Neely, J.G. A practical guide to surveys and questionnaires. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2011, 144, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bova, C.S.; Halse, S.J.; Aswani, S.; Potts, W.M. Assessing a social norms approach for improving recreational fisheries compliance. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2017, 24, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S.A.; Fulton, D.C.; Currie, L.; Goeman, T. He said, she said: Gender and angling specialization, motivations, ethics, and behaviors. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2006, 11, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.A. The meaning of leisure for women: An integrative review of the research. J. Leis. Res. 1990, 22, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, R.M.; Weber, J.D. Female anglers in a predominantly male sport: Portrayals in five popular fishing-related magazines. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2015, 52, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożewicz, M. Komunikat z Badań nr 151/2019: Konsumpcja Alkoholu w Polsce; Research report no. 151/219: Alcohol consumption in Poland; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wedgbury, A. The Meme Masculinity in the Online Angling Community. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Worcester, Worcester, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus, R. Understanding recreational angling participation in Germany: Preparing for demographic change. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2006, 11, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, P.; Arlinghaus, R. Differences between organized and non-organized anglers in an urban environment (Berlin, Germany) and the social capital of angler organizations. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 2008, 67, 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- EIFAC 2008. EIFAC Code of Practice for Recreational Fisheries. FAO EIFAC Occasional Paper 42, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rzym. Available online: http://fao.org/docrep/012/i0363e/i0363e00.htm (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Young, T.J. Questionnaires and surveys. In Research Methods in Intercultural Communication: A Practical Guide; Zhu, H., Ed.; Wiley: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyboer, E.A.; Embke, H.S.; Robertson, A.M.; Arlinghaus, R.; Bower, S.; Baigun, C.; Beard, D.; Cooke, S.J.; Cowx, I.G.; Koehn, J.D.; et al. Overturning stereotypes: The fuzzy boundary between recreational and subsistence inland fisheries. Fish Fish. 2022, 23, 1282–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurobarometer. Attitudes of European Citizens Towards the Environment; (No. 295); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aas, Ø.; Thailing, C.E.; Ditton, R.B. Controversy over catch-and-release recreational fishing in Europe. In Recreational Fisheries: Ecological, Economic and Social Evaluation; Pitcher, T.J., Hollingworth, C.E., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradidge, S.; Zawisza, M.; Harvey, A.J.; McDermott, D.T. A structured literature review of the meat paradox. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, L. Carbon offsets and shifting harms. Erasmus J. Philos. Econ. 2024, 17, 234–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulecka, O.; Czerwiński, T. Ryby małocenne—Kierunki wykorzystania [Low-value fish—Directions for use]. In Działalność Podmiotów Rybackich i Wędkarskich w 2017 Roku [Activities of Fishing and Angling Entities in 2017]; Mickiewicz, M., Wołos, A., Eds.; IRS: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, A.L.; Mulligan, H.; Kaemingk, M.A.; Coulter, A.A. Angler knowledge of live bait regulations and invasive species: Insights for invasive species prevention. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 3219–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumser-Lupson, K. Conflict and Coastal Aquatic Sports: A Management Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK, 2004. Available online: http://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/gees-theses/350 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Shilling, F.; Boggs, J.; Reed, S. Recreational system optimization to reduce conflict on public lands. Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, I. Endowment effect theory, prediction bias and publicly provided goods: An experimental study. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2008, 39, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inland Fisheries Act. Ustawa z dnia 18.04.1985r. o rybactwie śródlądowym. Dz. Ustaw 1985, 21, 91. [Google Scholar]

| Attitude Toward Angling | Average Non-Angler | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Neutral | Negative | |||||

| What is angling in your opinion? (stereotypes) | N | % | N | % | N | % | % |

| One of the many forms of spending time on the water 1 | 195 a | 92.0% | 239 a | 86.9% | 45 b | 75.0% | 87.1 |

| Sitting by the water for hours in solitude 2 | 142 a | 69.3% | 195 ab | 76.8% | 49 b | 83.1% | 74.3 |

| A time-consuming and costly hobby 3 | 76 a | 42.5% | 112 b | 55.4% | 45 c | 80.4% | 52.8 |

| Sporting competition and the pursuit of big fish 4 | 109 a | 59.9% | 96 b | 45.3% | 17 b | 35.4% | 49.8 |

| The opportunity to obtain fish to eat 5 | 142 a | 72.8% | 173 a | 68.7% | 28 b | 50.0% | 68.0 |

| Opportunity to spend time with family and friends 6 | 130 a | 65.0% | 131 a | 56.0% | 16 b | 27.6% | 55.8 |

| Associations with the sight of an angler near the water | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Likert | |||

| With drunken people wearing waders 7 | 1.90 a | 2.40 b | 3.45 c | 2.35 | |||

| With littering the shores 8 | 1.95 a | 2.33 b | 3.56 c | 2.34 | |||

| With polluting the aquatic environment 9 | 1.77 a | 2.04 b | 3.17 c | 2.07 | |||

| With killing fish for personal benefit 10 | 2.15 a | 2.56 b | 3.86 c | 2.57 | |||

| With unethical tormenting of fish for own pleasure 11 | 1.78 a | 2.30 b | 4.10 c | 2.33 | |||

| With environmental responsibility 12 | 2.96 a | 2.51 b | 1.70 c | 2.58 | |||

| With passion for nature 13 | 3.49 a | 2.96 b | 1.81 c | 3.02 | |||

| Social Associations and Stereotypes About Angling | One of Many Ways to Spend Time on the Water | Sitting by the Water for Hours in Solitude | Time-Consuming and Costly Hobby | Sport and the Pursuit of Big Fish | Provisioning | Opportunity to Spend Time with Family and Friends | Unethical Tormenting of Fish for Pleasure | Passion for Nature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglers’ Self-Reported Behavior | |||||||||

| Angling as non-primary activity % | 46.0% | ||||||||

| Different activities anglers (mean) | 3.93 1 | ||||||||

| Angling cumulative time/year (hours) | 296.83 2 | ||||||||

| Frequency of angling/year (days) | 61.33 3 | ||||||||

| Hours/day | 4.84 4 | ||||||||

| Angling alone | 65.7% | ||||||||

| Costs/year [EUR] | 551 5 | ||||||||

| Motivation to catch fish | 64.3% | ||||||||

| Motivation to experience emotions/thrills | 66.4% | ||||||||

| Motivation to sport rivalry | 16.7% | ||||||||

| Complying with C&K rules | 33.6% | ||||||||

| Motivation to supply diet with healthy meat | 27.9% | ||||||||

| Motivation to obtain additional income | 5.5% | ||||||||

| Angling with friends | 63.9% | ||||||||

| Angling with family | 57.2% | ||||||||

| Member of angling association | 49.6% | ||||||||

| Motivation to meet with friends | 46.6% | ||||||||

| Motivation to meet with family | 30.9% | ||||||||

| Complying with C&R rules | 62.6% | ||||||||

| Motivation to contact with nature | 88.4% | ||||||||

| Significant Predictors 1 | Positive Opinion (N = 158) | Negative Opinion (N = 42) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | W | b | W | |

| Participate in sailing, kitesurfing, windsurfing etc. | −1.494 | 5.915 * | 0.498 | 0.317 |

| Need for contact with nature | −0.403 | 7.339 ** | 0.104 | 0.161 |

| Need for acquiring knowledge and new skills | 0.308 | 5.748 * | −0.189 | 0.810 |

| Opinion that angling is sporting competition and chasing big fish | 0.685 | 7.403 ** | −0.242 | 0.275 |

| Connotation with passion for nature | 0.295 | 4.031 * | −0.493 | 4.137 * |

| Connotation with unethical tormenting of fish for pleasure | −0.373 | 6.350 * | 0.850 | 16.330 *** |

| Connotation with responsibility for the environment | 0.397 | 8.543 ** | −0.544 | 4.661 * |

| Connotation with a drunken man in waders | −0.455 | 9.434 ** | 0.273 | 1.598 |

| Model fit criteria | ||||

| −2 log Likelihood | 508.227 | |||

| χ2 goodness of fit (df = 680) | 2219.646 *** | |||

| Pseudo R2 of Nagelkerke | 0.473 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karpiński, E.A.; Skrzypczak, A. The Social Image of Inland Angling in Poland Within the Concept of Sustainability: A Factual and Stereotypical Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188444

Karpiński EA, Skrzypczak A. The Social Image of Inland Angling in Poland Within the Concept of Sustainability: A Factual and Stereotypical Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188444

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarpiński, Emil Andrzej, and Andrzej Skrzypczak. 2025. "The Social Image of Inland Angling in Poland Within the Concept of Sustainability: A Factual and Stereotypical Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188444

APA StyleKarpiński, E. A., & Skrzypczak, A. (2025). The Social Image of Inland Angling in Poland Within the Concept of Sustainability: A Factual and Stereotypical Analysis. Sustainability, 17(18), 8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188444