Abstract

This study examines how employees’ perceptions of environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) activities shape organizational commitment (OC), organizational identification (OI), and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in IT manufacturing firms. We further examine whether generational cohort membership moderates the relationship between ESG and OCB, comparing the MZ generation (Millennials, born 1981 to 1996; Generation Z, born 1997 to 2012) with the older generation. Using survey data from 374 employees across four Korean IT manufacturers and structural equation modeling, we find that S and G positively predict OC; E negatively predicts OC. G positively predicts OI, whereas E negatively predicts OI, and S is not significant. Both OC and OI positively predict OCB and mediate ESG→OCB links (OC mediates E, S, G; OI mediates E and G). Multi-group analysis shows a stronger G→OCB path for the MZ cohort than for the older cohort. In summary, the empirical analysis results of this study are expected to be helpful to executives and managers of IT manufacturing companies that are conducting or promoting ESG activities.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the necessity for businesses to align their strategies with the broader interests of humanity, society, and stakeholders, demonstrating that corporate growth and even survival cannot be sustained in isolation. This realization has significantly accelerated global interest in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles. An increasing number of firms, including large corporations, publicly listed companies, and multinational supply chain partners, are adopting ESG practices in response to evolving legal mandates and stakeholder expectations. ESG management refers to a company’s proactive efforts to protect the environment, promote social value, and establish robust and transparent governance systems. It extends beyond the pursuit of short-term profitability by incorporating a commitment to sustainable development, ethical conduct, and the minimization of adverse environmental and social impacts.

In today’s rapidly evolving business landscape, sustainability, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and the pursuit of shared value have emerged as critical priorities in organizational management, particularly for ensuring long-term survival and growth. While the initial discourse on ESG management primarily centered around private-sector corporations, it has since expanded to encompass a wide range of public institutions, including government agencies and state-funded organizations [1]. A strong organizational orientation toward ESG is increasingly recognized as a strategic asset, enhancing a firm’s ability to attract and retain talented employees while also fostering a heightened sense of purpose among internal stakeholders, thereby contributing to improved organizational productivity [2].

A review of the existing academic literature on ESG activities reveals that most studies have predominantly focused on financial, strategic, or marketing perspectives, often neglecting the organizational and behavioral dimensions. This narrow scope has hindered the evolution of ESG into a holistic, organization-wide initiative that engages all members of the firm. To address this gap, it is essential to empirically examine the causal mechanisms through which ESG initiatives influence key internal variables such as managerial performance, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), and employee productivity. Furthermore, as ESG management inherently reflects a transformation in corporate value systems, it is crucial to elucidate the dynamic interplay between a firm’s underlying values and its ESG orientation.

Between 2012 and 2021, the predominant keywords of domestic ESG-related research included “performance,” “value,” “investment,” “management,” and “sustainability,” reflecting a strong emphasis on financial and investment-oriented perspectives. Although references to environmental and carbon-related issues increased notably in 2021, scholarly attention to the implications of ESG for internal organizational members—such as employees’ perceptions, behaviors, and engagement—remained limited [3]. Accordingly, most prior studies examining the relationship between ESG management and organizational performance have primarily relied on ESG ratings published by external evaluation agencies as proxies for a firm’s ESG performance [4].

However, a review of the existing literature on corporate ESG activities reveals a notable gap in studies that explicitly examine the relationship between organizational identification and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). This gap is particularly salient in the information technology (IT) sector, where firms exhibit a high reliance on human capital. In such contexts, ESG initiatives are likely to play a critical role in fostering employees’ perceptions of meaningful work, thereby enhancing their engagement in discretionary behaviors such as OCB [5].

In the case of IT manufacturing firms, sustained investment in research and development is critical for maintaining competitiveness in rapidly evolving technological environments. The development and commercialization of advanced IT technologies heavily depend on the training and retention of highly skilled professionals. As such, systematic talent development and human resource management have become urgent strategic priorities. Against this backdrop, there is a growing need to investigate how ESG performance is perceived by internal organizational members and how these perceptions shape their attitudes and behaviors. Rather than examining ESG solely from a corporate-level or external stakeholder perspective, future research should focus on the lived experiences of employees who are directly involved in the implementation of ESG initiatives. This study aims to explore how employees in ESG-active organizations perceive their relationship with the organization and how such perceptions influence organizational attitudes.

Ultimately, this research seeks to reconfirm that ESG management has the potential to generate positive outcomes not only for internal members but also for a broader array of stakeholders. It further aims to provide practical insights into how organizations can effectively engage and empower their workforce in the pursuit of sustainability goals.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. ESG Activities and Organizational Commitment

ESG is a convenient word made up of the first letters of Environment, Social, and Governance. ESG management refers to management activities that transparently manage a company’s environmental responsibility, social responsibility, and governance [6], and ESG activities are recognized as a factor that has a significant impact on the sustainability and long-term value of a company by minimizing the disadvantages that a company may cause to the environment and society and maximizing the effectiveness of the governance structure [7]. In ESG, Environment refers to activities to protect the environment, such as carbon emission reduction, resource consumption reduction, waste discharge reduction, resource conservation, and eco-friendly production. Social includes responsibility for products, human rights protection, and respect for local communities and stakeholders. Governance is related to corporate efforts such as corporate management responsibility, protection of shareholder rights, and establishment of a monitoring system for the board of directors [8].

In addition, according to the empirical analysis results of Broadstock et al. [9], the results of a meta-analysis of Bloomberg’s ESG index on environmental responsibility activities, social responsibility activities, and governance activities confirmed that it had a positive effect on innovation capabilities, such as R&D activities, and financial performance, such as total profit. In a study on the effects of corporate ESG activities on internal employees’ organizational cohesion and organizational citizenship behavior, it was reported that conducting ESG management activities affects mid- to long-term corporate value and has a positive impact on the company and society [10]. Meanwhile, ESG, a non-financial factor, requires that a company’s economic activities be conducted on a sustainable basis, and investors evaluate the sustainability of the invested company from a long-term perspective. This serves as the basis for investors to consider non-financial performance, which is the company’s impact on the environment and society, along with financial performance [11].

Therefore, since the performance of ESG activities is very closely related to the company’s core stakeholders, effective ESG activities are expected to have a significant impact on the management of internal organization members and morale enhancement.

Organizational commitment is basically the tendency to identify with the organization and its members and to be absorbed in one’s job. It includes the desire to remain a member of the organization and trust in the organization’s goals, values, and behaviors and attitudes that strive for the benefit of the organization [12,13]. In addition, organizational commitment in the relationship between an organization and its members has been shown to have a broad positive effect on organizational behavior, such as increasing the job performance of organizational members and reducing turnover, absenteeism, and stress [14]. Regarding this type of organizational commitment, Meyer & Allen [15] divided it into three factors: affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment. The three elements of organizational commitment reflect desire, need, and obligation, respectively, so even if organizational commitment is only a single concept, it can have different effects on both goal intention and goal behavior through the three elements [16,17]. Looking at previous studies on operational commitment so far, most of them basically present emotional commitment as a component of organizational commitment [12,18], and when discussing organizational commitment in general, it refers to emotional commitment [19,20].

Recent empirical findings highlight ESG’s influence on commitment. Oh and Park [21] demonstrated that CSR activities—economic, social, and environmental—significantly shape organizational commitment. Kim and Kim [22] further confirmed that ESG practices in restaurant firms positively affect employee commitment. In SMEs, perceived authenticity of ESG practices was found to enhance all three forms of commitment—affective, normative, and continuance [17]. More recently, Lee et al. [23] showed that ESG-driven commitment among employees mediates improvements in internal satisfaction and alignment with organizational values. Based on these prior findings, the following hypotheses are proposed to examine the relationship between ESG management activities and organizational commitment:

Hypothesis 1:

ESG activities will have a significant impact on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 1-1:

Environmental (E) activities will have a significant impact on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 1-2:

Social (S) activities will have a significant impact on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 1-3:

Governance (G) activities will significantly impact organizational commitment.

2.2. ESG Activities and Organizational Identification

According to social identity theory [24], individuals tend to classify and identify themselves with various demographic and social categories, and furthermore, individuals use the social reputation or status of the organization to which they belong to evaluate their own worth. For this reason, individuals are more likely to identify with organizations that have an image that enhances their self-worth. Ashforth & Mael [25] presented the results of their analysis that when organizational members experience a high level of organizational identification, they accept the organization’s values and goals, and these values are internalized, which, in turn, leads to behaviors that gradually help the organization achieve its goals. It was reported that when organizational members experience a high level of organizational identification, they accept the organization’s values and goals, and these values are internalized, which, in turn, leads to behaviors that gradually help the organization achieve its goals [26]. Zappalà’s [27] research results show that organizational identification fully mediated continuance commitment to change and partially mediated emotional and normative commitment to change.

In addition, Lee and Jeon [28] stated that the higher the level of organizational identification, the more likely it is for members of the organization to engage in illegal activities for the benefit of the organization and its members. On the other hand, there are also research results showing that organizational identification has a negative effect on organizational members.

Recent studies have examined the role of ESG practices in strengthening organizational identification. Nguyen et al. [29] demonstrated that corporate social responsibility initiatives enhance both organizational identification and trust, which subsequently promote affective commitment. Yang and Hwang [30] found that ESG practices in travel platform firms improve employees’ organizational identification by elevating self-esteem and deepening psychological immersion. Likewise, Jeong et al. [31] reported that call center employees who perceive ESG practices positively exhibit stronger belongingness and pride, thereby enhancing identification and reducing turnover intentions.

Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed to explore the relationship between ESG activities and organizational identification:

Hypothesis 2:

ESG activities will have a significant impact on organizational identification.

Hypothesis 2-1:

Environmental (E) activities will have a significant impact on organizational identification.

Hypothesis 2-2:

Social (S) activities will have a significant impact on organizational identification.

Hypothesis 2-3:

Governance (G) activities will have a significant impact on organizational identification.

2.3. Organizational Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) is known to be a concept first used by Smith et al. [32], which refers to the voluntary and altruistic action by members of an organization for the benefit of the organization. Organizational citizenship behavior is organizational behavior that is performed voluntarily by members of the organization, unlike behavior that members are required to perform for official duties, and is helpful to the organization or colleagues. Therefore, it is conceptualized as voluntary behaviors performed by members to advance organizational interests without the expectation of formal compensation [33]. Izhar [34] also stated that organizational citizenship behavior is not a formal requirement for organizations to practice it. However, it was argued that it is the behavior of organizational members that helps them move in a better direction to effectively achieve the organization’s goals.

Meanwhile, McNeely & Meglino [35] classified organizational citizenship behavior based on whether the target of the behavior is an individual or an organization. It was divided into Organizational Citizenship Behavior Individual (OCBI) toward colleagues and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Organization (OCBO). OCBI stands for voluntary helping behavior toward colleagues. And empathy for the other person is considered an important related variable. OCBO refers to a behavior that takes the lead for the organization, and empathy for the other person is considered an important related variable.

OCBO stands for Taking Action for the Organization, and perception of fairness was said to be an important influencing factor. It is true that there are various criticisms in domestic studies due to confusion over the concept and definition of organizational citizenship behavior, but it is a well-known fact that organizational citizenship behavior is being studied as a factor that greatly influences job performance by expanding the concept of organizational performance [36,37,38]. For these ESG activities to be successful, factors such as voluntary participation of members, support, solidarity, and cooperation with colleagues are important. However, when empirically analyzing the relationship between these organizational behavior variables, there are methodological and realistic limitations in applying all organizational citizenship behavior variables that have been studied so far.

Therefore, we can see that researchers are conducting research focusing on some specific sub-dimensions. As an example, Kim Nam-Hyeon et al. [39] analyzed various components of organizational citizenship behavior as a single dimension through exploratory factor analysis to simplify the research model.

Prior empirical research consistently identifies organizational commitment as a critical antecedent of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), highlighting its role in motivating employees’ discretionary efforts that enhance organizational functioning [23,40,41]. Among its dimensions, affective commitment—employees’ emotional attachment and sense of belonging—has been most strongly associated with OCB. From the perspective of social exchange theory, such attachment fosters reciprocal behaviors that extend beyond formal role expectations.

Hwang and Min [42], in a study of nursing personnel, demonstrated that affective commitment significantly predicts OCB. Their results further revealed that perceptions of distributive justice shape affective commitment, which, in turn, fully mediates the link between justice perceptions and OCB dimensions such as altruism, conscientiousness, and civic virtue. Complementary evidence from Yang and Hwang [30] shows that ESG-driven organizational identification enhances self-esteem and organizational immersion, indirectly suggesting that psychological attachment facilitates positive discretionary behaviors.

Taken together, these findings underscore a robust link between organizational commitment and OCB. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3:

Organizational commitment will have a significant positive effect on the organizational citizenship behavior of organizational members.

2.4. Organizational Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

When organizational members attain a high degree of identification, they not only endorse the organization’s stated values and objectives but also internalize these principles as self-referent standards, thereby enacting behaviors that incrementally advance collective goals [26]. Organizational identification is conceptualized as the extent to which individuals construe their self-identity in terms of membership within a specific organization, exerting a pervasive influence on employees’ attitudes, discretionary behaviors, and commitment to organizational success [43,44,45]. Kim and Kim [46] further contend that such identification is fortified when there is substantive congruence between the organization’s articulated vision or mission and the personal value frameworks of its members. This effect is especially salient in public institutions, where high levels of identification are more likely to develop when an organization’s demonstrated commitment to social responsibility aligns with employees’ own social value orientations (SVO), thereby fostering stronger organizational attachment and prosocial engagement.

Park et al. [47], in their study on authentic leadership and employee performance, found that stronger social identification was positively associated with peer-oriented OCB. Similarly, previous research has demonstrated that OI positively influences organizational commitment (Kim, 2009, [48]) and enhances OCB across various organizational contexts [49,50].

In light of these findings, it is reasonable to posit a direct relationship between organizational identification and OCB. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4:

Organizational identification will have a significant impact on organizational citizenship behavior.

2.5. The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Identification

Recent empirical studies have increasingly positioned organizational commitment and organizational identification as sequential mediators that elucidate how organizational interventions yield critical outcomes ranging from productivity gains to enhanced cohesion and discretionary behaviors. Organizational commitment is conceptualized as the affective and normative bond that employees form with their organization, serving as a vital conduit through which strategic initiatives translate into heightened task performance and collective efficacy. By fostering emotional attachment and a sense of obligation, commitment motivates individuals to align their efforts with organizational objectives and to contribute beyond prescribed role requirements. Organizational identification, defined as the degree to which employees internalize their organization’s values and perceive its successes and failures as their own, further strengthens this mechanism by incorporating organizational goals into the self-concept. As identification intensifies, employees demonstrate increased propensity for organizational citizenship behaviors, voluntarily engaging in actions that support peer performance, innovation, and the broader organizational mission without expectation of formal rewards.

According to Dutton et al. [51], two core elements influence the process of organizational identification: the organization’s internal identity and its external image as perceived by employees. Perceived organizational identity refers to employees’ internalized beliefs about the essential characteristics of their organization. This identity emerges from employees’ subjective assessments, and when organizational attributes are perceived as attractive or meaningful, individuals are more likely to align themselves with the organization [52].

In general, job passion is known to foster both organizational identification and affective commitment, serving as a mediating mechanism for key outcomes such as reduced turnover intention and enhanced OCB [53]. Organizational identification has been shown to positively influence members’ proactive behaviors, job attitudes, commitment, and overall performance while negatively affecting turnover intention, absenteeism, and deviant behaviors [54,55].

Ngo et al. [56] demonstrated that organizational identification mediates the relationship between perceived organizational support and outcomes such as organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Similarly, Kim and Kwon [57], in a study of travel agency employees, found that organizational identification mediated the relationship between perceived ethical climate and turnover intention.

Collectively, these findings indicate that organizational identification plays a critical mediating role in shaping employees’ discretionary behaviors, including OCB. Building on this body of literature, the present study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5:

Organizational commitment will mediate the relationship between ESG activities and organizational citizenship behavior.

Hypothesis 6:

Organizational identification will mediate the relationship between ESG activities and organizational citizenship behavior.

2.6. Moderating Effect Depending on the Distinction Between the MZ Generation and the Older Generation

A moderating effect refers to the influence of an external variable that alters the strength or direction of the relationship between an independent and a dependent variable. In statistical terms, a moderator interacts with the independent variable, thereby changing its impact on the dependent variable.

The term MZ generation refers collectively to Millennials (born between 1980 and 1996) and Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012). This cohort matured during a period of rapid digital transformation, developed strong proficiency with emerging technologies, and, in many cases, grew up as only children, often internalizing a heightened sense of individual significance shaped by concentrated parental attention and affection [58].

These generational characteristics have also shaped their workplace attitudes and expectations. For instance, a study titled A Study on the Generation Gap between Millennial and Z Generations confirmed notable differences in job-related values and attitudes between Millennial and Generation Z public servants [59]. In addition, Yoo and Lee [60] conducted an empirical analysis on office workers in large corporations and found that generational differences influenced the relationships among turnover intention, organizational justice, pay satisfaction, career development support, and work engagement.

Building upon these findings, the present study posits that generational differences may moderate the relationship between ESG management activities (as the independent variable) and organizational citizenship behavior (as the dependent variable) in the context of IT manufacturing firms. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 7:

Generational differences will moderate the relationship between ESG management activities and organizational citizenship behavior in IT manufacturing companies.

Hypothesis 7-1:

Generational differences will moderate the relationship between environmental (E) activities and organizational citizenship behavior in IT manufacturing companies.

Hypothesis 7-2:

Generational differences will moderate the relationship between social (S) activities and organizational citizenship behavior in IT manufacturing companies.

Hypothesis 7-3:

Generational differences will moderate the relationship between governance (G) activities and organizational citizenship behavior in IT manufacturing companies

2.7. Research Model

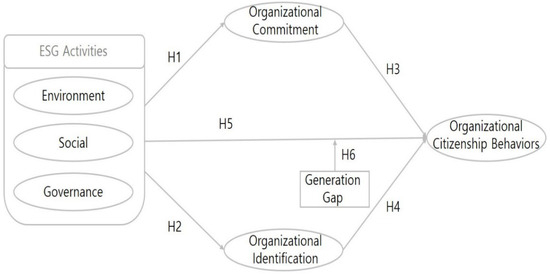

This study defined ESG activities as three factors: environment (E), society (S), and governance activities (G). The research model designed to achieve these purposes is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Operational Definition of Variables

3.1.1. ESG Activities

We conceptualize ESG activities as firm-level initiatives that proactively address climate change and environmental stewardship, promote societal well-being by supporting key stakeholders (e.g., employees and customers), and uphold legal and ethical standards. To operationalize this construct, the measurement items employed in the empirical analysis were adapted from the survey instrument originally developed by Kang [61] to align with the specific context of the present study.

The final questionnaire comprised 16 items, categorized into three dimensions: environmental (E; 4 items), social (S; 4 items), and governance (G; 4 items). Sample items included statements such as “My company makes efforts to conserve energy and resources” on a five-point Likert scale.

3.1.2. Organizational Commitment

In this study, organizational commitment is defined as a psychological state reflecting an individual’s proactive engagement with the organization, manifesting as a form of voluntary, intrinsic motivation and a willingness to support its survival and growth [62]. To measure organizational commitment, six items were developed based on the scale used in Hwang [63]. Example items include statements such as “I am proud to belong to my company” and “My company makes sincere efforts to listen to employees’ opinions.” All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale.

3.1.3. Organizational Identification

Building on prior research, this study views organizational identification as the cognitive process by which members embrace and integrate their organization’s goals and values into their own identity [64]. The measurement of organizational identification was adapted from the instrument developed by Lee [65]. The scale comprised five items, including statements such as “When someone praises the company I work for, I feel as though I am receiving a personal compliment.” Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale indicating the degree of agreement.

3.1.4. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) denotes discretionary actions that, while not formally rewarded, advance both individual development and organizational functioning [66]. Fundamentally, OCB comprises voluntary efforts beyond prescribed role requirements undertaken to bolster organizational effectiveness without anticipation of extrinsic rewards [33].

In this study, OCB was measured using six items adapted from the instruments developed by Senge [67] and Park et al. [68], revised to align with the research context. Sample items include “Employees in our company provide colleagues with useful work-related information” and “Employees help co-workers with excessive workloads, even when it is not part of their own responsibilities.” All items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2. Data Collection and Research Methods

Data for the empirical analysis were collected through a self-administered survey administered to employees in four leading IT manufacturing firms in South Korea. Firms were selected based on their industry prominence, market capitalization, and active engagement in ESG-related initiatives. Within each firm, human resource departments assisted in distributing the questionnaire to a stratified pool of employees across diverse functional areas (e.g., R&D, production, marketing, administration) to ensure representativeness.

The IT manufacturing sector was selected because it represents one of the most dynamic and globally competitive industries in South Korea, characterized by rapid technological change and substantial engagement in ESG initiatives. This context provides a relevant setting in which to examine how ESG practices influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors.

A total of 400 questionnaires (100 per firm) were distributed between 10 and 20 December 2024. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. Of the 400 surveys, 391 were returned (response rate = 97.8%). After data screening, 12 cases with more than 10 percent missing values and 5 cases failing attention-check items were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 374 valid responses for analysis. The final sample comprised 61.5% male and 38.5% female employees, with an average age of 35.7 years (SD = 7.9). Participants’ average organizational tenure was 7.2 years, and 71% held non-managerial positions. Descriptive and inferential analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 27.0, and confirmatory factor analyses and structural equation modeling were conducted with AMOS 27.0.

4. Results of the Empirical Analysis

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The results of frequency analysis to determine the demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

To evaluate the measurement model, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 27.0 to assess both reliability and validity of our constructs. Internal consistency was examined via Cronbach’s alpha coefficients computed in SPSS 29.0, where values of 0.60 or greater denote acceptable reliability. As reported in Table 2, Cronbach’s alpha for the environmental, social, and governance dimensions, as well as for organizational commitment, organizational identification, and organizational citizenship behaviors, all exceeded 0.80, indicating robust internal consistency across all scales. Convergent validity was established by inspecting standardized factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE). All standardized loadings were above 0.70; composite reliability values exceeded 0.70, and AVE values surpassed the 0.50 threshold. Discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which showed that the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded its correlations with other constructs.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity for the measurement model.

The goodness-of-fit indices for the measurement model were as follows: χ2 = 418.039 (df = 137, p < 0.001), χ2/df = 3.051, GFI = 0.902 (≥0.8), IFI = 0.946 (≥0.9), TLI = 0.933 (≥0.9), CFI = 0.946 (≥0.9), and RMR = 0.036 (≤0.05). These values indicate that the model meets the required fit criteria. Convergent validity was assessed based on standardized factor loadings of 0.5 or higher, composite reliability (C.R.) of at least 0.7, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.5 or higher, as recommended by Fornell and Larcker [69]. As presented in Table 2, all measurement items in this study met these thresholds, confirming convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the square root of the AVE for each construct with the correlation coefficients between constructs. As shown in Table 3, the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded the correlation coefficients between constructs, confirming that discriminant validity was achieved.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

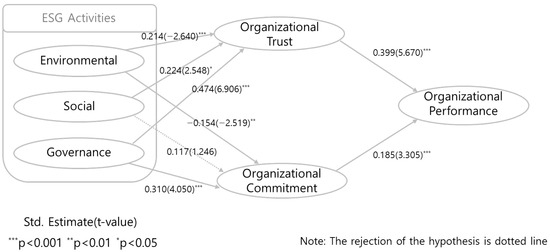

This study employed structural equation modeling (SEM) path analysis to examine the impact of ESG management activities on organizational commitment, organizational identification, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Additionally, it investigated the mediating effect of organizational commitment and organizational identification. Also, the moderating effect of the generation gap between ESG activities and organizational citizenship behavior was verified. The measurement model’s reliability and validity were confirmed, providing a solid foundation for testing the structural model. The results of the structural model fit analysis indicated χ2 = 418.039 (df = 137, p < 0.001) and χ2/df = 3.051, meeting the recommended significance level (p > 0.05). Moreover, the fit indices—NFI = 0.922, RFI = 0.903, IFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.933, CFI = 0.946, and RMSEA = 0.074—suggest that the model demonstrates an overall good fit. The results of hypothesis testing using structural equation modeling are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 2.

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis testing.

Figure 2.

Structural results of the proposed model.

First, Hypothesis 1 examined the impact of ESG activities in IT manufacturing corporations on organizational commitment. The analysis revealed that the environmental (E) factor (standardized coefficient = −0.292, t = −3.843, p < 0.001) was found to have a significant negative effect on organizational commitment, social (S) factor (standardized coefficient = 0.251, t = 2.548, p < 0.05), and the governance (G) factor (standardized coefficient = 0.577, t = 6.906, p < 0.001) had statistically significant positive effects on organizational commitment. Consequently, Hypotheses 1-1, 1-2, and 1-3 were all supported.

Hypothesis 2 examined the impact of IT manufacturing corporations’ ESG management activities on organizational identification. The analysis revealed that the environmental (E) factor (standardized coefficient = −0.171, t = −2.519, p < 0.05) had a statistically significant negative effect, while the social (S) factor (standardized coefficient = 0.107, t = 1.246, p = 0.213) was not statistically significant but the governance (G) factor (standardized coefficient = 0.309, t = 4.050, p < 0.001) had statistically significant positive effects on Organizational Identification.

Hypothesis 3 assessed the relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. The analysis showed a standardized coefficient of 0.374 (t = 5.670, p < 0.001), confirming statistical significance and leading to the acceptance of Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4 examined the impact of organizational identification on organizational citizenship behavior. The analysis results indicated a standardized coefficient of 0.213 (t = 3.305, p < 0.001), demonstrating a statistically significant positive effect. Hypothesis 4 was supported. According to previous studies on the relationship between organizational identification and organizational citizenship behavior, there are research results showing that organizational identification affects organizational citizenship behavior over a long period of time [70,71], and organizational identification is highly related to attitudinal variables such as job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment, and is closely related to non-job outcomes such as the organization’s job performance and organizational citizenship behavior [72]. These studies were also found to be consistent with the research results of Mael and Ashforth [73] and Van Der Vegt et al. [74].

Hypotheses 5 and 6 investigated the mediating effect of organizational commitment and organizational identification in the relationship between ESG management and organizational citizenship behavior. According to the analysis results, in the relationship between ESG management and organizational citizenship behavior, the organizational commitment was analyzed to have a mediating effect of environmental (E) factors, social (S) factors, and governance (G) factors, while organizational identification was found to have a mediating effect of environmental (E) factors and governance (G) factors.

The differential mediating roles of organizational commitment and organizational identification yield several theoretical insights. First, the finding that organizational commitment fully mediates the effects of environmental, social, and governance dimensions on organizational citizenship behavior underscores the centrality of social exchange processes in explaining how responsible management translates into discretionary employee actions. By demonstrating that each ESG component fosters a sense of obligation and reciprocity, these results extend stakeholder theory and social exchange theory, suggesting that ethical treatment of both external and internal stakeholders strengthens employees’ affective bonds and motivates voluntary contributions beyond formal role requirements.

Second, the selective mediation of organizational identification for environmental and governance factors but not for social factors highlights the boundary conditions under which identity-based mechanisms operate. Specifically, initiatives that signal a genuine commitment to environmental stewardship and governance integrity appear more likely to resonate with employees’ self-concept and become internalized as part of their work identity. In contrast, social initiatives, while effective in building commitment, may not by themselves evoke a strong sense of shared identity, implying the existence of alternative psychological pathways such as perceived organizational support or trust that warrant further theoretical investigation. Together, these insights support a dual-process model in which social exchange-driven commitment and identity internalization operate in tandem yet differentially to channel the impact of ESG management on organizational citizenship behavior. Table 5 presents the mediation effects tested for Hypotheses 5 and 6.

Table 5.

Mediating effect testing.

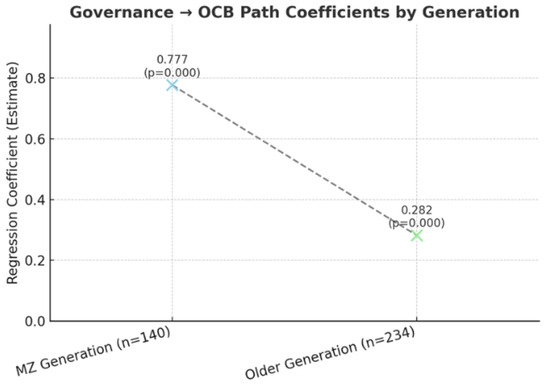

Hypothesis 7 examines the moderating effect of the generation gap on the relationship between ESG management activities and organizational citizenship behavior in IT manufacturing corporations. According to the analysis results, the governance factor (t = 5.834, p < 0.01) among the ESG activities of the MZ generation (30s and younger) showed a statistically significant positive result. Therefore, it was analyzed that there was a moderating effect of the generation gap. In addition, as a result of analyzing the moderating effect of the older generation (40s and older), it was found that the governance factor (t = 4.370, p < 0.001) among ESG activities had a moderating effect.

The finding that governance practices exert a stronger influence on organizational citizenship behavior among both younger (MZ) and older cohorts offers several theoretical implications. First, it underscores the universal salience of governance as a legitimacy-enhancing mechanism that transcends life-stage differences. Second, the differential strength of the governance–OCB link across cohorts invites integration with generational identity theory. Whereas environmental and social initiatives may resonate variably depending on career stage and personal priorities, governance appears to constitute a core organizational attribute that both younger and older employees internalize as part of their professional identity.

The chi-square difference test using AMOS was conducted to examine the moderating effect of the generation gap on the relationship between ESG activities and organizational citizenship behavior. The comparison between the unconstrained model and the constrained model showed a chi-square difference of Δχ2(1) = 16.052, with χ2 = 16.052, p = 0.001 (unconstrained model: χ2 = 921.166, constrained model: χ2 = 937.218; 937.218 − 921.166 = 16.052). Since this value exceeds the critical threshold of 7.81, the results indicate that the generation gap has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between ESG activities and organizational citizenship behavior. Consequently, Hypothesis 7 was supported. The significant moderating effect of generational cohort reveals that the strength of the linkage between ESG management and organizational citizenship behavior is contingent upon employees’ age group. Table 6 reports the moderating effects related to Hypothesis 7.

Table 6.

Moderating effect testing.

Table 7 compares the alternative models to evaluate the robustness of the findings. The results in Table 7 reveal that the constrained model exhibited superior goodness-of-fit, as evidenced by higher NFI, IFI, RFI, and TLI values, confirming the robustness of the proposed framework.

Table 7.

Comparison of models.

Figure 3 illustrates the moderating effect of generational cohort on the governance–OCB pathway. For the MZ generation, the path coefficient is both substantial (β = 0.777) and highly significant, whereas for the older generation, the corresponding coefficient is smaller (β = 0.282) yet remains statistically significant. This divergence in effect sizes underscores the presence of a generational moderation effect in the relationship between governance-oriented ESG activities and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior.

Figure 3.

Moderating Effect of Generation on Governance to OCB.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Integrated Summary of Empirical Findings

Overall, the empirical results of this study provide detailed insights into the ways in which ESG activities influence employee attitudes and behaviors in IT manufacturing firms. The social and governance dimensions of ESG exhibit a significant positive relationship with both organizational commitment and organizational identification. These findings suggest that transparent governance and responsible social practices encourage employees to internalize organizational values and strengthen their psychological connection with the firm. By contrast, the environmental dimension exhibits a weaker or, in some cases, even negative association with employee attitudes. One possible explanation is that employees often perceive environmental initiatives as distant from their immediate work responsibilities or as yielding benefits primarily for external stakeholders rather than for themselves. From the perspective of social exchange theory, individuals may reciprocate only when they perceive direct or tangible benefits; thus, initiatives such as carbon reduction or eco-friendly production may not generate the same sense of obligation or attachment as socially oriented practices. Moreover, the present analysis confirms that both organizational commitment and organizational identification act as critical mediating mechanisms through which ESG practices influence organizational citizenship behavior. This implies that ESG activities do not directly elicit prosocial behaviors; rather, they do so by fostering deeper emotional engagement and identification with the organization. Importantly, the limited or negative effects of environmental initiatives highlight the need for organizations to design environmental strategies that are perceived as authentic, employee-relevant, and aligned with internal, as well as external, stakeholder interests. Importantly, the moderating role of generational differences was also substantiated, revealing that MZ generation employees and older cohorts respond differently to ESG initiatives in shaping their behavioral outcomes. While governance and social practices generally elicited positive responses across groups, the environmental dimension showed weaker or even negative associations, particularly among older employees who often perceived such initiatives as peripheral to their immediate job relevance. This pattern resonates with prior evidence suggesting that environmental activities, when viewed as symbolic or externally oriented, can foster employee skepticism or disengagement [75,76]

Overall, the findings of this research broaden the ESG literature by redirecting attention from external stakeholders such as investors and consumers to employees and by empirically demonstrating the psychological mechanisms through which ESG initiatives yield positive organizational outcomes. The results underscore the importance of designing ESG strategies that focus on employees and cultivate both awareness of sustainability efforts and a shared sense of purpose within the organization.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The results of this study offer several theoretical and practical implications.

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

First, while extant research has extensively examined the effects of ESG activities on external stakeholders such as investors and consumers, empirical investigations into their impact on internal stakeholders, namely, organizational members, remain scarce. This study contributes to the literature by empirically investigating ESG management from the perspective of internal stakeholders, thereby expanding the scope of ESG research into the field of organizational behavior. Continued research in this area is warranted to deepen our understanding of the internal dynamics of ESG practices. Second, as ESG management becomes increasingly institutionalized across both public and private sectors worldwide, this study provides timely insights into which ESG dimensions companies should prioritize from an internal stakeholder perspective. Specifically, the findings suggest that before implementing ESG management strategies, organizations must first enhance employees’ awareness and understanding of ESG principles. This study further demonstrates that when employees exhibit strong organizational commitment and identification, they are more likely to display attachment to the organization and engage in organizational citizenship behavior.

This study contributes to theory by underscoring the cultural contingencies in how organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is perceived and enacted. In the Korean IT manufacturing context, shaped by collectivist norms and hierarchical structures, discretionary behaviors such as altruism, courtesy, and civic virtue may be viewed less as voluntary contributions and more as normative role obligations. This suggests that the pathways linking ESG activities to organizational commitment, identification, and ultimately OCB may operate differently than in Western settings, where OCB is often conceptualized as purely discretionary. Theoretically, these findings call for a more context-sensitive understanding of OCB and highlight the importance of embedding ESG–employee behavior models within cultural frameworks. By doing so, this study extends cross-cultural organizational behavior research and enriches theory on the boundary conditions under which ESG practices shape employee attitudes and behaviors.

5.2.2. Practical Implications

From a practical standpoint, this study underscores the shift in ESG-related research from traditional domains such as accounting and finance toward the field of organizational behavior. By focusing on internal stakeholders, this study encourages future research that connects ESG performance with behavioral and attitudinal outcomes within organizations.

Secondly, within IT manufacturing firms, environmental and governance aspects of ESG initiatives enhanced organizational commitment and identification, although their overall impact remained relatively modest. This highlights the need for firms to diversify and deepen their ESG initiatives. Establishing cross-functional ESG forums or internal communication channels could serve to strengthen employee engagement and raise awareness of ESG goals across organizational levels.

Third, the findings reinforce the importance of cultivating positive attitudes among internal members as a means of enhancing organizational performance. This study confirmed that both organizational commitment and organizational identification function as mediators in the relationship between ESG activities and OCB.

From a practical perspective, the results underscore that ESG strategies cannot be universally applied. Firms in knowledge-intensive sectors, such as IT and R&D-driven industries, may benefit from emphasizing governance and social initiatives that directly foster employee identification and commitment. By contrast, companies in resource-intensive or environmentally sensitive sectors should carefully design environmental initiatives to ensure their authenticity and perceived relevance to employees, thereby mitigating risks of skepticism or disengagement. Overall, the findings highlight the need for sector-specific ESG implementation strategies that not only enhance external legitimacy but also cultivate positive employee attitudes and discretionary behaviors within organizations.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study examined employees’ perceptions of ESG activities, a subject of growing interest among scholars and practitioners, and offered meaningful implications for both theory and practice. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged, which, in turn, provide opportunities for future research.

First, the generalizability of the findings is constrained by the sample and industry selection. Data were collected exclusively from employees of IT manufacturing firms in South Korea, which may limit applicability to other regions or sectors. Future research should broaden the sampling frame by including diverse industries and geographical contexts to enhance external validity.

Second, while this study focused on organizational commitment and organizational identification as mediating mechanisms between ESG management and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), additional factors may play important roles. Variables such as perceived organizational support, ethical climate, or employee engagement could further enrich the explanatory framework.

Third, the cross-sectional design of this study restricts causal inference. The observed associations between ESG activities, mediators, and OCB may reflect correlation rather than causality. Future studies would benefit from adopting longitudinal designs to capture temporal dynamics or experimental approaches to establish causal pathways more robustly.

Finally, although the research model was empirically tested, certain methodological limitations remain. Specifically, this study did not incorporate all dimensions of OCB identified in the prior literature, which may restrict the scope of interpretation. Therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing these results, and future research should aim to adopt more comprehensive frameworks that reflect the multifaceted nature of organizational behavior constructs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-C.J. and D.-S.C.; methodology, S.-C.J.; software, S.-C.J.; validation, D.-S.C.; formal analysis, S.-C.J.; investigation, S.-C.J.; resources, S.-C.J.; data curation, D.-S.C.; writing-original draft preparation, S.-C.J.; writing-review and editing, D.-S.C.; visualization, D.-S.C.; supervision, D.-S.C.; project administration, D.-S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as it involves no collection or handling of personally identifiable or sensitive information, and does not include any intervention or interaction with human subjects by Changwon National University Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This research used the sustainability reports which are freely available from each company’s webstie.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, S.M.; Lee, D.M. A Study on Analysis of Priority and Promotion Strategy for the Introduction of ESG Management in Public Institution. Korean Manag. Consult. Rev. 2022, 22, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Henisz, W.; Koller, T.; Nuttall, R. Five ways that ESG creates value. McKinsey Q. 2019, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Min, B.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kong, I.W. A study on the effect of ESG Perception of Organizational Members on Social Value Orientation, Organizational Identification, and Organizational Citizenship behavior. J. Soc. Value Enterp. 2022, 15, 57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, D.G. A Study on the Effect of ESG Management Performance Perceived by Employees on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Loyalty. Rev. Account. Policy Stud. 2024, 29, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.R.; Park, J.C. A Study on the Effects of ESG Activities of IT Companies on Employees’ Job Crafting and Job Satisfaction. Korea Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.S.; Seo, J.H. An analysis of the real estate value influenced by the characteristics of ESG management. J. Korea Real Estate Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, B.J.; Lee, H.Y. The effect of ESG activities on organizational trust, and organizational identity through employees’ organizational justice. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2022, 28, 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.N.; Han, S.L. The Effect of ESG Activities on Corporate Image, Perceived Price Fairness, and Consumer Responses. Korean Manag. Rev. 2021, 50, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Matousek, R.; Meyer, M.; Tzeremes, N.G. Does corporate social responsibility impact firms’ innovation capacity? The indirect link between environmental & social governance implementation and innovation performance. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Wang, Y.; Kim, J.Y.; An, D.C. The Effects of Corporate ESG Activities on Organizational Commitment of Employees and Their Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Korea Res. Acad. Distrib. Manag. Rev. 2022, 25, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.Y.; Pak, Y.S. The Effect of ESG Performance Feedback on the Internal and External Search Behaviors of Firms. Korean Manag. Rev. 2022, 51, 1409–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.Y.; Park, I.A.; Kim, H.N. The effects of perceived ESG attributions of LCC airline employees on ESG authenticity, organizational commitment, and loyalty. J. Tour. Sci. 2023, 47, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee–Organizational Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Organizational Commitment: Toward a Three-Component Model; Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario: London, ON, Canada, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, A.F.; Fayolle, A. Bridging the entrepreneurial intention–behaviour gap: The role of commitment and implementation intention. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2015, 25, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, S.K.; Kang, Y.J. A Study on the Effect of ESG Perception of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Employees on Organizational Commitment. Future Growth Stud. 2022, 8, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Boulian, P.V. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.; Wilson, C. Development of affective organizational commitment: A cross-sequential examination of change with tenure. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 56, 114–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. A Study on the Relationship between Organizational Culture and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Perceived by Naval Personnel: Mediating Effects of Affective Commitment and Moderating Effects of Interactional Justice and Coworker Social Loafing. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Soongsil University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.H.; Park, H.S. The Effect of Management Innovation on the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance. J. Digit. Converg. 2018, 16, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.O. The Effect of ESG Management Activities of Food Service Companies on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. J. Ind. Innov. 2023, 39, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.J.; Yang, J.M.; Kim, M.J. The Impact of ESG Management by Financial Institutions on Organizational Performance. Korean Corp. Manag. Rev. 2023, 30, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Masood, M. Transformational leadership, creative self-efficacy, trust in supervisor, uncertainty avoidance, and innovative work behavior of nurses. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2018, 54, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F.; Licciardello, S.A. Towards sustainable organizations: Supervisor support, commitment to change and the mediating role of organizational identification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Jeon, S.G. The Effect of Organizational Identification on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Focusing on Moderating Effect of Perceived Ethical Organizational Culture. Korean J. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2016, 19, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Pham, T.; Le, Q.; Bui, T. Impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment through organizational trust and organizational identification. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3453–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Hwang, Y.H. Effects of ESG initiatives on Employees’ Sense of Belonging and Self-Esteem in Travel Platform Companies. J. Sustain. Manag. Res. Soc. 2024, 8, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.S.; Choi, S.R.; Park, S.R. Emotional workers’ ESG activities recognition on organizational identification, and intention to stay: Focusing on call center workers in major insurance companies in Gwangju. Korea J. Bus. Adm. 2023, 36, 577–608. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H. Relationship Between ESG Activities, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Productivity, and Management Performance—Focusing on the Moderating Effect of Corporate Values Perception. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Convergence Industry, Graduate School of Seoul Venture University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Izhar, O. Organizational citizenship behavior in teaching: The consequences for teachers, pupils and the school. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2009, 23, 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- McNeely, B.L.; Meglino, B.M. The role of dispositional and situational antecedents in prosocial organizational behavior: An examination of the intended beneficiaries of prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.S. Organizational Citizenship Behavior of New Venture Employees: Antecedents and Consequence. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.H. The Effects of Transformational and Transactional Leadership on LMX, Organizational Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior -Focused on Local Workers of Korean Small and Medium Sized Firms in China-. J. Chin. Stud. 2019, 89, 199–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, S.H. Analyzing the Impact of Airline Cabin Crew s Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Citizenship Behavior on the Effect of Leader-Member Exchange Relationship. Korea Acad. Soc. Tour. Manag. 2019, 34, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.H.; Park, B.G.; Song, K.S. A Study on the Relationships among Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Personal Characteristics, Job Characteristics, and Attitudes of Organizational Members. J. Organ. Manag. 1999, 23, 51–82. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhshi, A.; Sharma, A.D.; Kumar, K. Organizational commitment as predictor of organizational citizenship behavior. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.A.; Min, H.Y. Influence of Clinical Nurses’ Organizational Silence on Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment Moderated by Organizational Justice. J. Korean Nurs. Adm. Acad. Soc. 2024, 30, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Jang, K.R. Antecedents of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors among Employees in Sport Organizations. Korean Soc. Sociol. Sport 2005, 18, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.W.; Chung, T.W. The Relationships among Group Cohesiveness, Organizational Commitment, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Sport Organizations. J. Sport Leis. Stud. 2008, 32, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.M.; Choi, K.K. Structural relationship among Leader-Member Exchange, Organizational Commitment, Organizational Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Sports Center. Korean Soc. Sports Sci. 2022, 31, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.H. The Impact of Public Sports Organization Members’ Perception of ESG Management on Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Focusing on the Mediating Effect of Social Value Orientation and the Moderating Effect of Employment Type. Asia-Pac. J. Converg. Res. Interchange 2024, 10, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.Y.; Seol, H.D.; Lee, J.H. The Relationship between Authentic Leadership and Employee Performance: Mediating Effect of Social Identity and Moderating Effect of 7Perceived Social Exchange Relationship. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 27, 2013–2039. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H. The Individual-Organizational Identity and Organizational Involvement. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2009, 16, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ersoya, N.C.; Borna, M.P.; Derousa, E.; Van der Molena, H.T. Antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior among blue- and white-collar workers in Turkey. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2010, 35, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Cho, D.H. The Effects of Person-Organization Fit, Organization-Based Self-Esteem on Organizational Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2015, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effelsberg, D.; Solga, M.; Gurt, J. Transformational leadership and follower’s unethical behavior for the benefit of the company: A two-study investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, D.; Tamplin, A.; Park, R.J.; Kyte, Z.A.; Goodyer, I.M. Development of a short leyton obsessional inventory for children and adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chung, H.I. The Influence on Organizational Performance of Job Passion, and the Mediating Effects of Organizational Identification. Korean Bus. Educ. Rev. 2022, 37, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.; Loi, R.; Foley, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L. Perceptions of organizational context and job attitudes: The mediating effect of organizational identification. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kwon, M.H. Ethical Climate and Turnover Intentions in Travel Agency -Mediating of Trust and Organizational Identification-. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2011, 11, 496–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shon, J.H.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, H.S. A study on the response of each generation to the communication characteristics of the MZ generation-Focusing on Generation MZ, Generation X, and Baby Boomers-. J. Commun. Des. 2021, 77, 202–215. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lim, S.G.; Lee, G.; Kim, H.J. A Study on the Generation Gap between Millennial and Z Generations. Korean Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 36, 23–46. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Yoo, S.W.; Lee, C. The Relationships among Turnover Intention, Organizational Justice, Pay Satisfaction, Support for Career Development and Work Engagement of the Millennial Generation and Z Generation Office Workers in Large-sized Enterprises. J. Corp. Educ. Talent. Res. 2022, 24, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.T. A Study on the Effect of ESG management on Financial Performance in Hotel Companies: Focused on Mediating Effects of Authentic Leadership and Affective Organizational Commitment. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Kyonggi University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, Y.K. The Effect of Empowerment Adoption on the Relationship Between Leadership and Organization Commitment in Hotel Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Kyonggi University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.Y. A Study on the influence of perceptions of organizational politics and perceived organizational support on Organizational Commitment in Public Organizations: Focused on intermediary effects of organizational trust and job satisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Soongsil University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.R. Role of Hi-Tech Call Center Employees’ ESG Activity Recognition in Increasing Corporate Performance via Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction. J. Digit. Contents Soc. 2024, 25, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. The Impact of ESG on casino employees’ Organizational Identification, Self-Esteem, and Job Satisfaction: Group Differences between K and P Casinos in Korea. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, T.S.; Organ, D.W. Job Satisfaction and The God Soldier: The Relationship between Affect and Employee “citizenship”. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Crown Pub: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, J.H.; Jeong, Y.A. Relationship of Personal and Organizational Value with Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Korean Corp. Manag. Rev. 2014, 21, 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergami, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self—Categorization, Affective Commitment and Group Self—Esteem as Distinct Aspects of Social Identity in the Organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, R.; Grojean, M.W.; Christ, O.; Wieseke, J. Identity and the Extra Mile Relationships between Organizational Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y. The Impact of Organizational Members’ Perceptions of Travel Companies’ ESG(Environment Social Governance) Activities on Organizational Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Tour. Enhanc. 2024, 12, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.A.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vegt, G.S.; Van De Vliert, E.; Oosterhof, A. International Dissimilarity and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Inter a Team Interdependence and Team Identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. J. Bus. Ethics. 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Skarlicki, D.P.; Paddock, E.L.; Kim, T.Y.; Nadisic, T. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: The moderating role of CSR-specific relative autonomy and individualism. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).