1. Introduction

Sustainability is a critical global objective, and green energy, particularly photovoltaic (PV) technology, plays a pivotal role in achieving it [

1]. While the literature provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing PV product purchase intentions, to fully achieve sustainability goals, it is essential to consider the potential of integrating environmental, social, and economic dimensions [

2,

3,

4]. In brief, green energy is generated from renewable resources and is naturally replenished, resulting in minimal environmental impact [

5]. Among the possible alternatives to generate green energy, solar photovoltaic is recognised as one of the most prevalent and least expensive forms of renewable energy because it does not require an existing public infrastructure [

5]. Technically, PV systems convert sunlight into electricity, offering a renewable and clean energy source that can significantly reduce reliance on fossil fuels and decrease greenhouse gas emissions [

6]. The use of PV products is a promising approach to reducing energy waste and promoting sustainability [

7]. Due to technological advancements, PVs promise higher efficiency and lower material consumption, which further enhances the sustainability of solar energy systems [

8]. This transition to solar energy is essential for sustainable development, as it provides a reliable and nearly limitless power source.

Utilising these photovoltaic products is perceived as one of the efforts in contributing to the 12th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG): Responsible Consumption and Production. As consumers become more environmentally conscious, they are more likely to switch to eco-friendly purchases. Ref. [

9] noted that Generation Z in emerging markets such as China are more aware of environmental issues and tend to purchase more sustainable products. In addition, approximately 40 per cent of the Asian population in 2035 will be Generation Z [

10], and they are expected to dominate the consumer market over the next decade. Given their uniqueness in this context, it is essential to study pro-environmental behaviour, such as PV product PI, among Chinese Gen Z. Due to the vast potential of this generation, this study aimed to reveal the purchase intent (PI) of Chinese Gen Z on PV products in China, as they tend to demonstrate their environmental consciousness by purchasing environmentally friendly products [

11].

Empirically, numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the determining factors of consumers’ pro-environmental behaviour in different contexts [

12,

13]. However, the study that particularly focused on PV products is relatively scarce. For instance, Ref. [

14] focused on sustainable products, Ref. [

15] studied organic products, and Ref. [

16] investigated green products. Therefore, there is an urge to examine the determining factor that significantly influences the PI of PV products, especially for Chinese Gen Z. In fact, past studies have integrated environmental factors into the TPB to provide a more comprehensive understanding of Gen Z’s intentions and behaviours, especially in areas like green tourism [

17] and waste management [

18]. However, there is a lack of studies that incorporate environmental responsibility and consciousness into the TPB to reveal the purchase intentions of PV products through the lens of Gen Z. This study is deemed to fulfil the underlying gaps, and most importantly, this demographic is increasingly recognised for its potential to drive sustainable practices due to its unique values and behaviours [

19].

Theoretically, consumers’ behavioural intention (BI) could be explained by utilising the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) as has been conducted previously [

20]. However, the literature has not yet reached a consistent result regarding the effect of the three dimensions in the TPB on behavioural intention. For instance, Ref. [

15] found an insignificant effect of attitudes (ATT) towards BI, while Ref. [

14] found otherwise. Similarly, inconclusive findings were also found in subjective norms (SN), in which Refs. [

16,

20] found a significant effect of SN, but an insignificant effect was also documented [

12,

21]. Moreover, although the significant influence of perceived behavioural control (PBC) is dominant in the literature [

22], an insignificant role of PBC is still found in a few studies [

15].

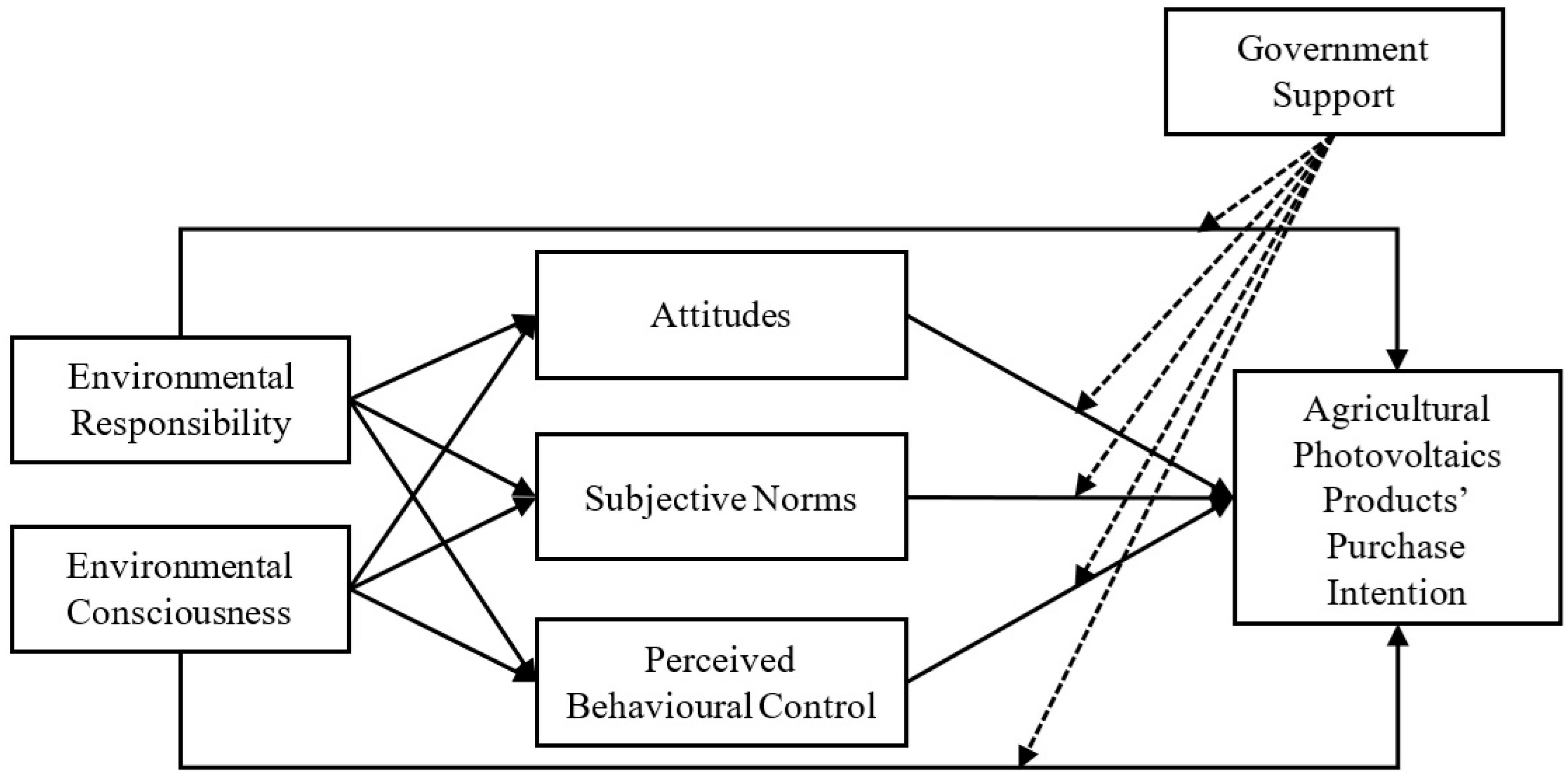

In addition, as the TPB was introduced to predict general behaviour, therefore, it has to be extended by other constructs to better explain pro-environmental behaviours such as PV product purchase intention. In addition to that, the TPB emphasises more on self-interest and social approval, while overlooking other influences such as personal norms [

23], even though an individual’s behaviour could be influenced by an individual’s green motivations and obligated morality [

12]. Therefore, extending the TPB model with two exogenous variables to reflect the influence of personal norms (environmental responsibility (ER) and environmental consciousness (EC)) could address the paradoxical strain and comprehensively predict Gen Z PI towards PV products. ER and EC are chosen as their substantial effect in influencing the sustainable behaviour has been widely recognised in past studies [

22,

24,

25,

26]. Therefore, this study further postulates that both ER and EC have a direct and indirect impact on PI on PV products as well.

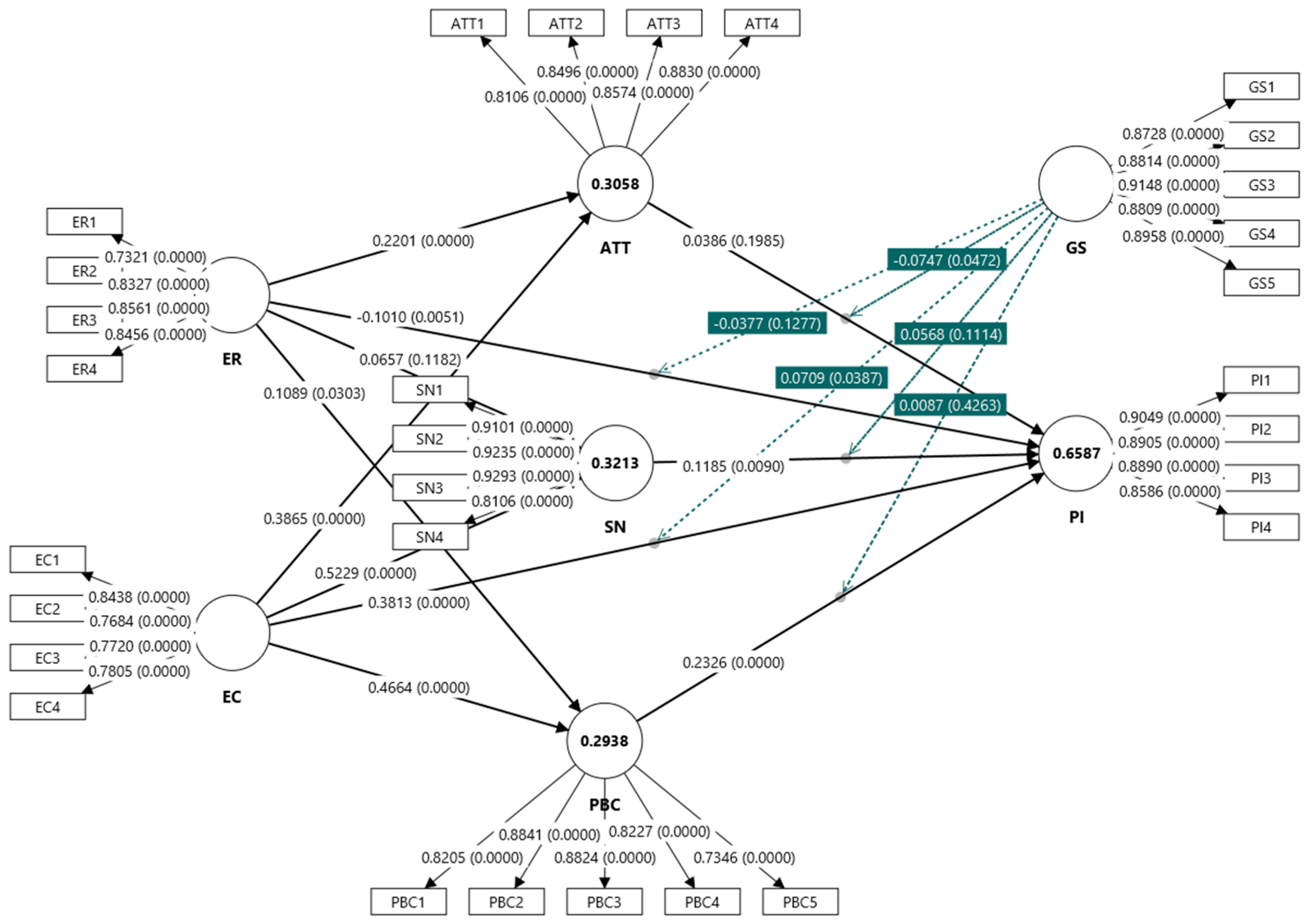

Overall, three research questions have been raised in the study, including (1) what are the factors that significantly determine Gen Z to purchase PV products? (2) Do three dimensions of the TPB (i.e., ATT, SN, and PBC) significantly mediate the relationships between ER and EC on PI? and (3) does government support (GS) strengthen the effect on the direct relationships between proposed antecedents and the PI of PV products? Therefore, based on these research questions, this study aims to examine the determinant factors of Gen Z in purchasing PV products by extending the TPB with two exogenous variables that reflect personal norms (ER and EC) and by examining the mediating effect of the three dimensions in the TPB in the relationship between the two exogenous variables and PI on PV products. This study examines the moderating effect of GS on the direct relationship between the antecedents and the PI of PV products, recognising the government’s crucial role in promoting environmentally friendly behaviours. The contribution of this study is fourfold: Firstly, contextually, this study examines the factors that determine the PI of PV products. Secondly, a novel framework is proposed in this study by extending the TPB with two exogenous variables that reflect the influence of personal norms in explaining the PI of Generation Z towards PV products. Thirdly, the research demonstrated that SN and PBC can significantly mediate the associations between exogenous variables and PI on PV products. Lastly, the study details the significant moderating effect of GS on the association between EC and PV product PI.

5. Discussion

The factors that significantly influenced the younger generation in China to purchase PV products were examined in this study. Surprisingly, ATT has no significant influence on PI, and this contradicts Refs. [

14,

20,

32]. This implies that the PI of PV products is not influenced by ATT, and thus, the personal evaluation of sustainability is not a decisive factor for their sustainable behaviour. As remarked by Ref. [

45], the sustainable behaviour of Gen Z is influenced by factors other than ATT, such as the influence from the social circle, as well as the feasibility of the behaviour, as proven in the study. This further signified that the younger generation in China are more collectivist, whereas their behaviour tends to be affected by others. In addition, the respondents might have limited knowledge and experience with PV products, and this could be the reason for the lack of significant results, as the term PV is more technical or jargon for them, compared to other sustainable products.

As hypothesised, both SN and PBC have a significant relationship with PI. These findings validate the results of Refs. [

16,

22], which emphasised the significant influence of SN and PBC on the PI. Gen Z in China are likely to purchase PV products if the people who are important to them and surrounding them feel that purchasing these PV products is good and protects the environment. Moreover, if consumers perceive that purchasing these products is easy to perform and does not require any additional effort or cost, then they will buy them.

In addition, inconsistent findings were reported for the two exogenous variables that reflect personal norms. The results revealed that ER has a significant negative influence on PI, and this finding is in disagreement with Refs. [

21,

24,

25]. This indicates that even though the younger generation feel they are aware of environmental problems and obligated to protect the environment, it will reduce their PI on PV products. One of the possible reasons is that Gen Z might not be familiar with the benefits of PV products, as they might have limited involvement with PV products. With that, they may not understand how PV products can mitigate environmental issues, although they feel responsible for them. In addition, the study further found that EC has a significant positive effect on PI, which coincides with prior studies [

22,

26,

35]. This showed that Chinese consumers are willing to purchase PV products if they are conscious of environmental issues.

Moreover, ER only significantly affects two of the three dimensions in the TPB, except SN. The significant influence of ER on ATT is similar to Refs. [

12,

31], which means consumers will have favourable and positive attitudes if they feel responsible for protecting the environment. The significant relationship between ER and PBC is in line with Ref. [

31] but contradicts Ref. [

12]. This result proved that a higher level of ER will increase the ability of the younger generation to purchase PV products, and thus make it easier to purchase them. However, the insignificant connection between ER and SN refutes the works of Ref. [

31] and shows that individual responsibility does not influence SN. Although Gen Z feel that they are responsible for environmental problems, their responsibility does not necessarily become an external influence that will eventually affect their behaviour. With that, no significant effect of ER on SN is found.

Additionally, as hypothesised, the three dimensions of the TPB are significantly influenced by EC. Similar findings were also revealed in previous studies such as Refs. [

12,

22,

37]. The findings indicated that Gen Z have favourable ATT, greater social pressure, and strong PBC if they are more conscious of environmental issues. Furthermore, two of the three dimensions in the TPB were proven to significantly mediate the association between EC and PI. Specifically, SN and PBC significantly mediated the relationship between EC and PI. As suggested by Ref. [

39], a stronger PBC would be established with high environmental concern and thus influence the green concept adoption intention. With that, the study proved that SN and PBC could play a mediating role in influencing PV products’ PI. However, the three dimensions of the TPB are found to have an insignificant mediating effect on the relationships between ER and PI. This is consistent with the direct effect of ER on PI. The sense of environmental responsibility still does not affect the PI on PV products, although the three dimensions of the TPB’s presence act as mediators. As explained earlier, the limited understanding of PV products of the younger generation could be the main reason. As this generation have insufficient understanding of PV products, the personal evaluation of PV products, influence from others in the social circle, as well as the feasibility of purchasing PV products, did not mediate the influence of ER on PI.

Lastly, the significant moderating role of GS is also found in this study, especially in the relationship between EC and PI. The finding is similar to Refs. [

44,

46], and showed that the association between EC and PI could be further strengthened with the presence of support from the government. This signified that the Chinese Gen Z perceived that GS is important to reinforce the relationship of EC towards PI in purchasing PV products.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study provides substantial contributions to the existing literature from a different research context that focuses on PV products. Firstly, two exogenous variables were added to the proposed model to reflect the influence of personal norms, and it was discovered that one of these variables has a significant direct influence on the PI of PV products. In addition, the results demonstrated that two exogenous variables had a significant impact on the three dimensions of the TPB. This indicates that the two exogenous variables not only have a direct effect on PI, but also have a direct correlation with the three dimensions of the TPB. As the initial model only explained the general behaviour, the TPB model should be expanded with additional variables that can capture the specific and unique characteristics of the research context. Moreover, the three dimensions of the TPB were used as mediators in the relationship between two exogenous variables and PI, and the results demonstrated that SN and PBC could significantly mediate the relationship between EC and PI. Finally, GS was proposed as a moderator to examine its moderating effect on the relationship between direct relationships and PI. The results indicated that GS significantly moderates the relationship between EC and PI to purchase PV products. Therefore, the moderating role of GS should not be overlooked, as it may influence the BI of consumers to engage in specific pro-environmental actions.

6.2. Practical Implications

In terms of practical perspectives, this study also offers several practical implications for stakeholders to increase the PI of Chinese Gen Z on PV products. Firstly, the results showed that SN, PBC, and EC have a significant effect on PI. Therefore, to achieve SDG 12, stakeholders such as government agencies, PV product manufacturers, and marketers have to focus on these three variables to increase the PI of consumers on PV products. For example, government agencies have to disseminate information regarding ecological problems to the public, as this could increase their awareness and consciousness. As found in this study, EC is important in influencing all three dimensions of the TPB and also the PI to purchase PV products. Therefore, increasing consciousness could bring a favourable ATT, greater social pressure, and also stronger PBC for them to purchase PV products. In addition, when consumers receive more information and are aware of ecological issues, they will feel more responsible and become more obligated to protect the environment by purchasing environmentally friendly products.

The influences of people surrounding Gen Z are also important, as they could put social pressure on them to purchase PV products. As Gen Z are youth consumers, therefore, they are likely to seek an opinion from those who are important to them. For instance, the marketers of PV products have to spread and share the benefit of purchasing PV products with people who are important to the younger generation, such as families and friends. Consumers are likely to purchase PV products if people surrounding them encourage them to purchase or have a favourable perception of those products as the findings indicated that the younger generation are more towards collectivism rather than individualism. Moreover, the marketers and sellers of PV products have to reduce the difficulty of purchasing PV products. For example, PV products have to be labelled with a special label or packaging for consumers to easily identify them. Shops may also allocate a designated place to market all the products that are produced through this concept. In addition, special discounts or promotions or marketing events to promote these PV products may be implemented by the businesses to attract greater PI.

In addition, PV manufacturers have to reform the PV products to make them more user-friendly. As explained earlier, this younger generation may have limited exposure and experience with PV products, and this has led them to be unaware of the benefits of PV products. With that, PV manufacturers are required to redesign the PV products so that they can be used more easily. The way of installation and the instructions of operation also have to be clearly provided so that they will reduce the difficulty level of Gen Z when they want to use it.

Furthermore, to increase the PI of PV products, policymakers have to play their role. For instance, government and their agencies have to articulate some policies and strategies to increase consumers’ willingness to purchase these PV products. Governments may provide certain incentives or rewards to consumers who purchase PV products, as well as give publicity support regarding the benefits of PV products, as this is important to enhance the awareness and consciousness of the younger generation and result in increasing their PI. Therefore, to increase the PI of the Chinese Gen Z, all stakeholders, including governments and businesses, have to play their role, as this is not the sole responsibility of consumers.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Recommendations

This study aims to investigate the significant factors that determine Gen Z in China to purchase PV products. Two exogenous variables have been integrated with the TPB to reflect the personal norms to examine their influence on PI on PV products. In addition to that, the three dimensions of the TPB were also utilised as mediators to examine the indirect influence of two exogenous variables on PI. Moreover, this study further included GS as a moderator to examine its moderating effect on the relationships. With the responses gathered from 675 Gen Z in China, the study revealed that PI is significantly influenced by SN, PBC, and EC. Moreover, ER significantly affects ATT and PBC, while the three dimensions of the TPB are significantly impacted by EC. The mediating test further found that SN and PBC significantly mediated the relationships between EC and PI. Additionally, the moderating analysis revealed that the association between EC and PI is significantly strengthened by GS.

Although several contributions were provided, several other limitations appear in this study. Firstly, this study only focused on general PV products and was not specific enough on which type of PV products. Therefore, future study is encouraged to narrow down the context of the study to focus on more specific PV products, as they may have different results. In addition to that, this study solely focused on Gen Z. Thus, it would be interesting if future studies could include other consumer groups, such as working adults and older generations, as different behaviour may be found. In addition, this study assumed all respondents were homogeneous, but different subcultures may exist. This would open an opportunity for future studies to consider the heterogeneity of the respondents, such as male vs. female, younger vs. older, and parent-subsidised vs. self-earning respondents. Moreover, the future study also suggested utilising other theories to examine the subject matter, such as social cognitive theory or the norm activation model, as this study employed the most commonly used theory (TPB) to understand the BI of Gen Z in purchasing PV products.