1. Introduction

The international second-hand clothing trade is a huge global commercial network that provides the main source of garments for millions of impoverished consumers in the world’s poorest countries. The wholesale trade was valued at over 4.9 billion dollars in 2024, and an estimated 24.2 billion individual items of apparel were exported from developed economies (see explanation in

Section 3.2) [

1] (UN Comtrade, 2025). Used apparel is primarily traded from affluent societies in Asia, Europe and North America to sub-Sharan Africa, Central America, Eastern Europe and some of the developing economies of Asia. It has a direct impact on the livelihoods of many of the world’s poorest people and the economies of low-income countries [

2] (Grüneisl, 2025). Fashion is one of the world’s most expansive and resource-intensive consumer sectors [

3] (Fletcher, 2013). The export of 4,848,586 metric tons per year of used clothing, as reported in the UN Comtrade, shapes the sustainability of the entire industry. Despite this large economic and environmental silhouette, the trade receives limited attention from policy makers, only occasional mentions in the international media, and it has been under-explored within the academic literature on sustainability [

4] (Brooks, 2019).

In addition to this empirical lacuna, the international second-hand clothing trade demands further critical attention due to new market trends that are disrupting the onward sale of high-value garments, and the way in which the used clothing networks fits within conceptions of a ‘circular economy’ [

5] (Brooks et al. 2017). First, the growth in peer-to-peer retail via online platforms, such as Vinted, is using digitalization and connectivity to enable new patterns of used clothing commerce within developed economies [

6] (Failory, 2023). Vinted’s economic model is characteristic of the growth of industry 4.0 as a platform dependent on the integration of digital technologies into everyday life [

7] (Da Costa et al., 2019). Secondly, within the fashion sector, as sustainability has become an important value for brands, retailers and consumers, the way in which garments are re-sold, at either national or global scales, has become an important indicator of the sector’s contribution to a circular economy [

8] (MacArthur, 2013). Despite the avowed enthusiasm among key industry players for a circular fashion economy, evidence suggests that there has been limited progress towards this objective. Rather, the used clothing trade may be undermining any transition towards a truly sustainable fashion sector [

9] (The OR, 2025). Lower levels of material and energy use would require a more fundamental transformation of market relations. Slowing cycles of production and consumption is the type of radical action that is ultimately required to disrupt the dominant fast-fashion production and retail model. A shift towards a slow fashion approach that prioritizes sustainability, ethical production and the longevity of garments could meet this goal [

10] (Sellitto et al. 2021).

The research gaps this article addresses provide an overview of the international used clothing trade patterns and discuss its contribution to sustainability and the circular economy. The article sets out the main features of the international second-hand clothing trade and explores its economic and environmental impacts. The first results section (

Section 3.1) provides an overview of the origins and structure of the trading networks, drawing on evidence from historical and contemporary source material. Next, the most important export patterns are mapped out to indicate the major sources and sinks of used garments, via analysis of UN Comtrade data (

Section 3.2). Thirdly, the economic impact of imports on sink nations are investigated (

Section 3.3), highlighting the ways in which low-value used clothes have out-competed domestic clothing industries or crowded out the opportunities for industrial development. Here, evidence focuses on under-development in sub-Sharan Africa and draws on data from key nations. The next section of results (

Section 3.4) considers the environmental impacts of the trade, both on destination countries— drawing on local reporting—and conceptually at a global scale. The final section of results (

Section 3.5) sketches out the recent growth in peer-to-peer retail in Europe.

Following the presentation of this research evidence, the used garment networks are discussed in relation to the circular economy, examining both the current contribution and the potential and limits of clothing re-use systems. The conclusion section serves the main aim of the paper in evaluating if the second-hand clothing trade is a sustainable industry, with reference to not just the environmental impacts, but also the cultural and economic sustainability of the international second-hand clothing trade for the world’s poorest people.

2. Materials and Methods

In a study which maps processes across different global locals and is based upon an industry where there is limited public documentation of trade patterns, there are practical methodological difficulties to navigate. The research objective was to map the main features of the international second-hand clothing trade and explore if and how the sector contributes to sustainability. This was undertaken by looking at the current state of the sector on a global scale, but with a focus on the UK and sub-Saharan Africa. The methodology involved both drawing on previous studies and being reflexive to the topic under enquiry. Rather than testing a single hypothesis, a broader evaluation of the used clothing trade was completed. The central research question was ‘Is the international second-hand clothing trade economically and environmentally sustainable?’

When reviewing the literature prior to research design, identifying past studies that had explored comparable global trade networks that could inform the methodology was difficult. To undertake this research, multiple steps were followed. The first objective was to understand the collection of used clothing commodities in the Global North. This was addressed through secondary data and analysis of reports on used clothing collection activities by key industry actors. As the UK is one of the largest exporters in the international trade, it was selected as the focus for the research. To find the principal organizations involved in the sector, a systematic online research process was undertaken using key terms. From this careful process the most prominent and reoccurring organizations were identified via online mapping. The qualifying criteria for selecting sources was that they must be a national scale organization with a long-standing involvement, spanning over 5 years in the international second-hand clothing trade.

The principal organizations involved that were selected for the research sample were the following NGOs: Human, Oxfam, Salvation and the Textile Recycling Association. The most prominent key industry players from the fast-fashion and circular economy include the following: H&M, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and Vinted as the largest peer-to-peer resale organization. To triangulate this, publicly available resources for the UK government’s All Party Parliamentary Group on Ethics and Sustainability in Fashion and the industry group The Textile Think Tank were consulted, as well as the limited academic literature, all of which further corroborated the importance of these organizations in the international second-hand clothing trade. Once identified, the websites of the organizations were analyzed as well as publicly accessible reports from the last three years. These were reviewed and sections of text relating to five different key areas were identified: clothing collections, clothing exports and imports, economic impacts, environmental impacts and peer-to-peer retail. Due to the variety of data sources and different formats of outputs, they were manually coded. This involved reading through websites and other documents at least three times and assigning descriptive labels (codes) to segments of text associated with different elements of sustainability. The data were then grouped by codes into broader categories to identify patterns of industry practice, and the original sources were re-read to validate the findings and address the research questions. Data from these qualitative texts provided the basis for the sub-sections of Results (

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

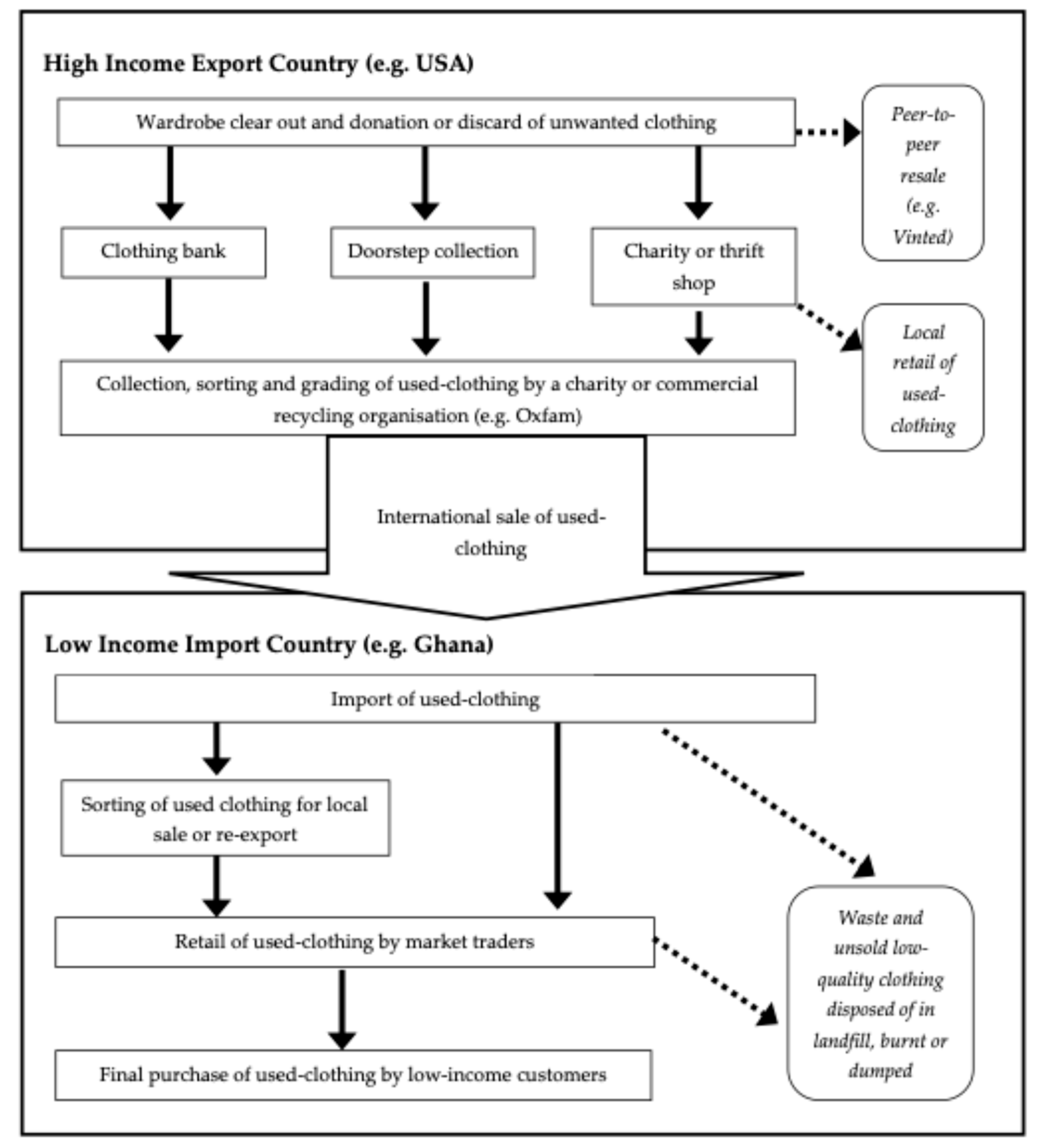

Section 3.4) and enabled an accessible overview of the second-hand clothing trade to be mapped out as a conceptual flow chart (

Figure 1). However, this review process did not provide sufficient information on two key aspects: the major global patterns in the used clothing trade and the national impacts of used clothing imports in the world’s poorest countries.

As the qualitative data did not provide evidence of the overarching global patterns of trade, the second stage was quantitative research. Taking a mixed methods approach helps to provide a holistic picture and validate the trade patterns that were described in qualitative texts. Quantitative research was based on analysis of the United Nations Comtrade data set. Here, the most recent data was accessed. The primary quantitative evidence in

Section 3.2 draws upon analysis of UN Comtrade data and follows the approach of Frazer (2008) [

11]. The most recent available UN data was cleaned (with missing and incomplete data removed), tabulated (appropriately summed and ranked by size) and presented in table format. All the UN Comtrade statistics quoted are under SITC code 26901 ‘Bulk textile waste, old clothing traded in bulk or in bales’, and all commodity values are converted from national currency into US dollars using exchange rates supplied by the reporter countries or derived from monthly market rates and volume of trade. Export figures are used in place of import figures, due to the greater reliability of export reporting in the used clothing trade. This methodological approach followed an earlier study. See Brooks and Simon (2012) [

12] for further discussion. Across the study, the temporal dimensions were the most recent data from UN Comtrade, accessed in 2025, but mapping 2024 data, and publications primarily from the last three years, although older, as appropriate from the qualitative data. On a geographical scale, the UN data is global, and the qualitative data was from the UK and linked English language resources.

It was beyond the scope of this project to undertake new primary field research into the national impacts of used clothing imports in the world’s poorest countries. However, the author has previously undertaken extensive field work in sub-Saharan Africa and multiple field studies since 2010 that have been previously published elsewhere. See [

4,

13,

14] (Brooks, 2019; Ericsson and Brooks, 2014; Brooks 2013). To build upon this and to investigate the wider economic impacts of the second-hand clothing trade at a macro level (

Section 3.3), existing trade reports (as detailed above) were consulted. Additionally, the work of advocacy and campaign NGOs, academic studies and other gray literature were systematically reviewed. Like the review of textile recycling organizations, key search terms on the economic, social and cultural impacts of used clothing imports in Africa were used. The environmental assessment also drew upon a range of published sources, including Greenpeace and the OR.

3. Results

3.1. The International Second-Hand Clothing Trade

The starting point of the international second-hand clothing trade is the overconsumption of cheap fast fashion, primarily in Europe and North America [

15] (Cline, 2013). The persistent marketing of new product lines and the constant cycles of buying, wearing and discarding clothing means there is an abundant supply of billions of re-useable garments that have limited economic value in their local markets. For the majority of people who can readily afford to buy new items, unwanted clothes that are outgrown, worn-out, unfashionable or no longer needed are either discarded as part of the household waste for commercial disposal, deposited for recycling or donated for resale by charities. Alongside the limited number of clothes resold via peer-to-peer networks (e.g., Depop, eBay, Vinted, discussed in

Section 3.4), the local sale of used clothing in charity stores (as predominant in the UK) or thrift stores (commonplace in the USA) represents sustainable re-use of clothing. However, due to the limited demand for second-hand clothing in developed economies, the majority of collected used garments are processed for export, via large and well-established networks, including many of the donations made to charities such as Oxfam [

16] (Gregson and Beale, 2004).

Used clothes are typically sourced via doorstep collections, clothing banks or in-store donations. From there, the majority will never reach over-saturated domestic second-hand markets and instead will be processed for export (see

Figure 1). Processing plants work to transform disorderly and random deposits of garments into valuable export commodities. Clothes pass along conveyor belts where pickers sort out different categories—such as women’s blue jeans or men’s colored t-shirts—and discard soiled items, unwearable rags and rubbish. The industry standard is for sorted clothes to be wrapped in 100 lbs/45 kg bales and packed into shipping containers. Sometimes, unsorted clothing is shipped directly to a low-income country where the garments are sorted before being re-exported. However, as transport costs are high, relative to the value of the commodity, and the highest-grade clothing is disproportionately profitable, sorting prior to export is more common. Intricate and perplexing supply networks have long been a feature of the global trade [

17,

18] (Haggblade, 1990; Velia et al., 2006), but what is clear is that this is overwhelmingly a commercial trade pattern, and the used clothes collected by charities and clothing recyclers alike are exported to the Global South and sold for profit [

19] (Baden and Barber, 2005). Across used clothing networks, there is limited knowledge among those who donate unwanted garments of their ultimate destinations, and the final consumers in countries such as Kenya, Mozambique and Zambia are equally unfamiliar with their previous lifecycles [

20] (Hansen, 2000). The world’s richest and poorest people are intimately linked when the latter pull a t-shirt over their head that months earlier someone a world away took off and threw away.

3.2. Import and Export Patterns

The second-hand clothing sector is global in reach but is not universal. It has particular geographies shaped by economic, political and social forces. The low value of used clothing means that it may be used as mark-up cargo to fill vessels to capacity, or act as the return freight on shipping routes, so it can be shaped by other economic relationships. Diaspora networks can link export and import countries; these are especially beneficial as there is frequently a lack of trust between commercial partners in second-hand clothing businesses due to the inherent variability of the goods [

21] (Abimbola, 2012). Cultural values can also be important as clothing products from some export countries are of greater value as they suit particular downstream markets.

UN Comtrade data shows 4,848,586,806 kg of clothing was exported in 2024. This includes a mix of light (e.g., underwear), medium (e.g., shirts) and heavyweight items (e.g., coats). Less bulky, lightweight items are most commonly traded internationally, and light apparel is preferred in primarily warm and tropical climates of export destinations. Therefore, taking the average item to be a 0.2 kg t-shirt, the total weight of the global exports is equal to 24.2 billion items.

3.2.1. Exports

As shown in

Table 1, the top 20 export countries account for 90% of the global trade in used clothing by value (USD 4.5 billion). As the two largest economies in the world, it is as expected that the USA and China fill the top two positions, but they are there for different reasons. The USA is the world’s biggest fast-fashion market and has long been the most significant source of used clothing, with its primary destination being Central America. However, American used clothing is not the most desirable type in many foreign markets and has a lower value because it is often ill-fitting. For instance, in West Africa, clothing shipments from the USA are typically cheaper than items from the UK because the average waist size in the USA is greater and clothes are less likely to fit slimmer African bodies. After the UK, which is a clear third by value and has strong cultural ties with many destination countries and a long history of domestic clothing recycling, most of the exporters are the advanced EU economies, as well as South Korea and Australia.

Chinese exports of used clothing have risen dramatically over the last 10 years, from 133 million kg in 2015 to 1.147 billon kg in 2024. Chinese exports are now greater than the combined weight of UK and USA exports but are only worth half the amount in dollars. As the UN data includes bulk textile waste, and China is the world’s largest manufacturer of clothing, which is primarily fast fashion for high-income countries, much of the Chinese exports are of waste rather than pre-worn clothes. This can include faulty clothing goods (seconds) and shoddy (torn textiles) apparel waste to be used in industrial processes, as well as used clothes.

Pakistan, Malaysia and India all feature as major exporters. For the two South Asian nations, there is clear evidence of their roles as re-exporters. Indeed, in India, used clothing imports for the domestic market have been banned. Clothing sorting plants operate in special economic zones where they export sorted and graded used clothing to secondary markets, primarily in East Africa [

22] (Norris, 2010). As the value of imports exceeds Malaysian exports, it suggests that Malaysia (see

Table 2) follows a similar pattern to Pakistan.

3.2.2. Imports

Used clothing is primarily exported to a wide range of low income-countries from a narrower set of rich nations. To determine the twenty major importers of used clothing, the destination of exports from the twenty largest exporters was used (

Table 2). The most significant destination is Pakistan, which has an important domestic market for used clothes—especially from the UK where diaspora networks link supply and demand—but also serves as a processing hub for re-export. The presence of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) comes in second among the top destination for exports, despite it being a relatively advanced economy with a small population. Its absence from the list of exporters (

Table 1) suggests that either used clothing is very popular in the UAE—a hypothesis we can reject given the limited retail market for second-hand clothes—or it acts as a shipping hub, and the second-hand clothes are re-exported. This demonstrates a limit of the UN Comtrade data (which is the best available data set) in recording the ultimate destination for used clothing exports.

The remainder of the top twenty listed is mainly populated by low-income countries in Central and South America, Africa and Asia. It is in these marketplaces where large volumes of used clothing imports provide the major sources of clothing for local people [

23] (Maclean, 2014). Ukraine is the eighth biggest destination, but, by weight, imports far fewer garments than nations with comparable dollar values of imports such as Ghana, the Philippines and Poland. This is most likely accounted for by the re-sale of used military clothing and other high-value items to meet demand from the countries’ armed forces. Poland has historically been a major recipient of out-of-season styles from Western Europe.

A notable outlier at number 20 is Japan, one of the world’s most affluent consumer societies; this is for a very particular reason. Japan imports a small volume of high-value collectable vintage clothing primarily from the USA. In Japan, items such as distressed denim jeans, leather jackets and iconic fashion labels are highly prized, with interest in Americana stemming from the post-war era when many US troops were stationed in Japan and influenced the fashion culture [

24] (Yoshimi and Buist, 2003). This type of high-value, niche re-use of fashion is very different to the overwhelming pattern of the international second-hand clothing trade, but serves as an example of the ways in which economic value can be restored in used clothing articles, and showcases that there is the potential to foster regimes of re-use that value previously discarded garments [

25] (Fletcher, 2016).

3.3. Economic Impacts

Imported used clothing provides a cheaper source of garments than equivalent new apparel and is thus preferred by low-income consumers in the impoverished nations which import the bulk of global exports. In countries where there are sorting and grading facilities, often in export processing zones, this work provides opportunities for value adding and revenue generation. However, large imports of used clothing to economies with persistent real trade deficits, such as Ghana and Kenya, harms their economic situation [

26] (Stop Waste Colonialism, 2025). Moreover, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, the trade has faced persistent attempts to ban and control imports, due to its negative economic and cultural impacts. This includes the case of Rwanda, where imports face a punitive tariff of

$2.50 per kilogram [

27] (Africanews, 2024). “The objective is to see many more companies produce clothes here in Rwanda,” said Telesphore Mugwiza, an official at Rwanda’s ministry of trade and industry, speaking when the ban was first implemented [

28] (quoted by Gambino 2017). Rwanda has faced recent pressure from the United States to relax trade controls, but other more powerful countries have persistently regulated the trade. India has long successfully maintained an outright ban on used clothing imports and protected their domestic industry. Regarding culture, Mugwiza continues to explain how there is an issue of human dignity and independence for Rwandans: “It is also about protecting our people in terms of hygiene. If Rwanda produces its own clothes, our people won’t have to wear T-shirts or jeans used by someone else. People need to shift to [this] kind of mindset.” Sales of used underwear are common in Africa (see

Figure 2). Global economic structures have left some consumers so impoverished that the only underwear they can afford are previously worn items discarded by affluent consumers in rich countries. The international second-hand clothing trade is not providing a dignified sustainable solution to these consumers.

Counter perspectives are that it was economic liberalization in the 1990s that killed the African clothing industries and that eliminating used clothing imports will not address the underlying economic problem [

11] (Frazer, 2008). Additionally, some advocates for the trade highlight the entrepreneurial opportunities enabled by second-hand clothing imports, which can be tailored, adding value and recreating new commodities [

29] (Textile Recycling Association, 2020). However, these are niche enterprises; most pre-worn garments are simply re-sold in the same condition as they were discarded in the Global North.

Today, the African continent lacks an industrial base. Previously, there were periods of economic modernization in the 1970s and 80s that built fashion industries, which used African-grown cotton to manufacture garments for local and international markets; this helped boost local economies and met indigenous culture desires for appropriate clothing. Since then the closure of clothing factories in countries including Mozambique, Nigeria and Zambia has been directly attributed to the import of used clothing [

12] (Brooks and Simon, 2012), and in countries like Rwanda, with limited manufacturing capacity, the imports crowd out the opportunity for local producers to establish themselves in domestic markets. However, the same is true of cheap new clothing imports. It is also common for used clothing to be illegally imported into African countries like Zimbabwe where import duties are circumvented and cheap used clothes have had widespread negative impacts on local businesses [

30] (Mafundikwa, 2024).

Trade controls on second-hand clothing could contribute to sustainable industrial development as part of a wider economic policy. Continued uncontrolled imports of used clothes from the West present a barrier to the development of infant clothing industries. Furthermore, it is concerning that organizations such as Oxfam, Humana and the Salvation Army that champion sustainability and charitable values, are among the major beneficiaries of the international second-hand clothing trade. Despite their knowledge of the harms caused by the trade, the following has been said: “Oxfam GB recognizes the potential negative impact that the export of donated textiles can have on the countries where they are sent to, which include impacts on human rights, local economies and the environment.” [

31] (Oxfam, 2021). But they argue Oxfam must “extract the most value out of the donations we have been entrusted with”. Any broad positive impacts these NGOs have in pursuing an agenda of advocacy and direct action in their wider policy work on sustainability and poverty reduction must be measured against their immediate roles in the used clothing trade and the broader effect they play as figureheads in the used clothing trade. NGOs promote the legitimacy of the entire international second-hand clothing sector that holds the poor in a relationship of dependency and furnishes them with garments like used underwear, which undermines their dignity. The trade is both a symptom and a cause of Africa’s persistent impoverishment.

3.4. Environmental Impacts

The international second-hand clothing trade is frequently cited as a socially and environmentally sustainable sector because it reuses materials. Oxfam for instance argues that “Donating and buying clothes with Oxfam is a powerful choice to support people around the world to tackle the inequality that fuels poverty.” [

32] (Oxfam, 2024). As discussed, this positioning of the trade as an anti-poverty initiative is problematic, especially as Oxfam is a major exporter of used clothing, which it does for the following reason: “In order to extract the most value out of the donations we have been entrusted with, we sell thousands of tonnes a year of textiles to third-party customers, and often that is with a view to those textiles being exported” [

33] (Oxfam, 2021). Oxfam subsequently highlighted what they frame as the environmental benefits: “When you’re buying second hand clothes, you’re promoting circular fashion by ensuring that existing clothing is worn until the end of its lifespan” [

32] (Oxfam, 2024), and while it is the case that it is sustainable to reuse wearable clothing goods rather than recycle the materials, suggesting that by donating used clothing you are also contributing to a circular fashion system elides the wider position of the trade within the fast-fashion ecosystem. Most collected used clothing is exported and the trade is an efficient system of transferring garments from places where there is limited market demand to new places where there is a ready market for cheap apparel, but this is just pushing the problems of fast fashion downstream from rich to poor countries, and many collected clothes will never be re-worn but end up as unrecycled waste. The root cause of the problem is the rampant overconsumption of new fashion. The process of disposing unwanted clothing provides the space for more unsustainable new clothing consumption. If consumers want to contribute to sustainability, the message for them is simple: do not buy new fast fashion, and re-wear useable clothes rather than get rid of them. When viewed from a systems perspective, rather than addressing the fundamental unsustainability of the fast-fashion sector, the used clothing sector serves to provide a seemingly virtuous outlet for old garments. As Oxfam put it, the trade is good as it will “tackle the inequality that fuels poverty” [

32] (2024).

In addition to the role the second-hand clothing trade plays within the wider material culture of the fast-fashion sector, the huge volume of imports has negative environmental impacts in the low-income countries that are acting as a sink for the textile waste of rich societies. The effect of the billions of unsold used clothing items that are shipped to poor countries is difficult to quantify; it is one of the many hidden aspects of the trade. Opponents of the trade have gone as far as to call the trade a form of ‘waste colonialism’, a term used to demonstrate how power relationships are articulated through the dumping of rubbish, pollutants and hazardous materials in impoverished countries [

26] (Stop Waste Colonialism). For instance, it is estimated that nearly half of the 15 million items of clothing imported to Ghana every week are unsellable. Many go to informal dumpsites or are burned in public warehouses, leading to air, soil and water contamination [

9] (The OR, 2025). Greenpeace [

33] (Omondi, 2024) reports dangerously high levels of toxic substances in indoor air at processing facilities, microplastics pollution and the accumulation of textile waste smothering ecosystems, polluting rivers, and creating ‘plastic beaches’ covered in apparel waste along the coast of Ghana. Like many sub-Saharan African countries, in Ghana, there is little or no infrastructure for recycling unsold garments, and these textiles ultimately become rubbish that is dumped, buried or burnt.

3.5. Peer-to-Peer Retail

The international-second hand clothing trade is all about creating new value from old clothes, and while the sector is as old as the clothing industry itself [

34] (Strasser, 1999), it continues to evolve and find new means to enhance profitability. The new technology characteristics of Industry 4.0 are utilizing digitalization to this effect. A new evolution in the second-hand clothing trade draws on the abundance of decentralized information technologies, namely the way that any smartphone can be used as a shopfront for the re-sale of secondhand clothes. Retail platforms that use peer-to-peer technologies including Depop, eBay, and especially Vinted have led to a boom in pre-loved and vintage fashion. This Lithuanian company, that started in 2008, has grown to become Europe’s largest online clothing marketplace with over 100 million users across 22 countries. As a smartphone-first platform, it makes selling old clothes directly to other peer consumers as frictionless as possible, with no seller fees, and by integrating the postal process.

What is different about peer-to-peer trade networks is that due to the proportionately high postage costs associated with individual clothing purchases, they are centered on domestic markets. What drives profitability is the way in which Vinted specializes in helping vendors to maximize the price of their old garments and uses algorithms to pitch items to browsing online shoppers. Fashionable goods with designer labels are prized and the existence of a frictionless medium for reselling designer fashion may deprive the charity stores and thrift shops of these commodities. The platform even enables authentication services to build trust between peers. This model of reuse is more sustainable than exporting large volumes of used clothing, especially if it deters the consumer from buying more new fast fashion. However, this requires further investigating as, rather than being a simple solution, on a wider scale, Vinted could be promoting a culture of overconsumption if it is feeding the growth of the overall clothing market in a new way. By encouraging consumers to clear out their wardrobe and make some extra income, it could be catalyzing another cycle of new retail fast-fashion consumption, rather than facilitating a circular economy. At a global systems-level, rather than being a sustainable solution, peer-to-peer selling may be enabling an ever-greater, ever-faster consumption of new fashion.

4. Discussion

The central research question was “Is the international second-hand clothing trade economically and environmentally sustainability?”. Evidence from the research has clearly demonstrated the unsustainable practices that are reproduced through these global economic networks that contribute to economic inequality and mass consumption of fast fashion. The economic and environmental impacts of the trade are discussed here. The international second-hand clothing trade maps the contours of inequality in the world economy. Exports shipped to the top 20 import countries represent 55% of the total value of all global used clothing exports, whereas the top 20 exporters send out 90% of the total value of used clothing exports. In simple terms, this means that there is greater variety in the used clothing import destinations than the export origins. This is in keeping with an unequal world: there is a concentration of wealth in the richest economies and far greater levels of fast-fashion consumption, whereas most of the world in lower-income economies have fewer opportunities to buy clothes. In marketplaces flooded with used-clothing imports, there is little space for affordable alternatives to wearing discarded garments. As well as being a marker of income inequality, the shipment of waste clothing to impoverished countries is a system of exporting rubbish from societies with unsustainable patterns of fast-fashion consumption. This waste colonialism has negative impacts on the environments and livelihoods of the world’s poorest people and inhibits their prospects of developing their economies.

Advocates for the international second-hand clothing trade such as [

35] The Textile Think Tank (2025) argue that the sector is ‘a pillar of circularity’ citing three ways in which the trade contributes to sustainability: (i) it reduces textile waste by diverting clothing form landfill, (ii) lowers the carbon and water footprint of clothing consumption as reusing garments requires 70% less emission, and (iii) it boosts secondhand markets in Africa, Asia and Latin America, creating jobs and affordable fashions. As the results demonstrate, each of these three conceptions is flawed.

First, in terms of reducing waste, what is really required is to slow cycles of consumption in the Global North rather than push the problem of clothing rubbish downstream. When old clothes ‘go away’ to charities or textile recyclers, people are not confronted by their unsustainable consumption patterns. Conversely, by providing a virtuous outlet for consumers to have a wardrobe clear-out, both the international used clothing trade and, potentially, peer-to-peer selling, are providing more space for consumption, although more research is required to map the broader life cycle impacts and sustainability of peer-to-peer resale at a global systems-level.

Secondly, in terms of water footprint and emissions, both issues would be better addressed by lower consumption of sustainably produced garments or slow fashion—that is, treating the root cause rather than trying to ameliorate the consequences of overconsumption. Furthermore, from a social justice perspective, if the world market routed new clothing manufacturing directly to marketplaces in the Global South, rather than excess clothing transiting through the wardrobes of the world’s most affluent consumers, then the poor would have access to newer garments, and less energy would have been expended in their transport.

This leads on to the third and final issue. While retailing used garments does provide a livelihood for people in low-income countries such as Mozambique, one of the major global importers, my own field research has demonstrated that these livelihoods still leave the traders in poverty [

13] (Ericsson and Brooks, 2014). Moreover, the work is less profitable than the equivalent trading work of selling imported new clothing. Beyond retail employment, the impact of clothing imports on deepening trade deficits in low-income countries is a chronic issue. Low-income countries would be boosted by building—or resurrecting—infant industries like clothing manufacturing. That would contribute to their industrialization and further their independent development in place of deepening the relationships of structural dependency.

5. Conclusions

There is a simple oft-repeated maxim in sustainability: “reduce-reuse-recycle”. It is better to reuse old clothes than recycle them. Less energy and material inputs are required to deliver wearable second-hand clothes, and making effective use of the current global stock of garments encapsulates the type of approach we should be taking towards consumption. A vibrant trade in used clothing could contribute to making the fashion sector more sustainable, but only as something which displaces the fast-fashion industry rather than as a secondary economic system that feeds off the excesses of overconsumption in rich societies. The second-hand clothing trade is pitched as a sustainable solution by its advocates. However, ultimately it is the reduction in consumption of new clothing in the first place which is the only way to transition to sustainability in the fashion sector. It is easy for advocates of the trade to make the simple, intuitive argument that the international second-hand clothing trade, as well as peer-to-peer retail, are sustainable circular systems that re-use billions of items and should be commended. However, as the results presented here illustrate, the international trade has detrimental downstream economic, cultural and environmental effects in low-income countries. Both the export of clothing and peer-to-peer sales facilitate wardrobe clear-outs, and fuel increasingly fast-fashion consumption in rich societies. Potential donors of used clothes to Oxfam and other clothing recyclers should be made aware that the most sustainable clothes they can wear are those they already own. Old clothes do not go away; they go somewhere to people with less power and choice, and the trade can contribute to locking them into relationships of dependency, cultural deprivation, and cause environmental harm.

In terms of policy recommendations, key players in the second-hand clothing trade should look to maximize domestic retail if they are serious about sustainability. Here, they could mimic some of the strategies used by peer-to-peer platforms to enhance their profitability. For fashion producers that want to move toward a more circular business model, a focus on fewer high-quality durable lines and a shift towards slow fashion principles could resolve some of the underlying challenges, but this is difficult to achieve in a cultural context that prizes that aesthetic value of ever-changing fast-fashion designs. Future research could further interrogate the social and cultural impacts of used clothing consumption in low-income countries. Additionally, more work is needed to investigate the linkages between fast-fashion consumption and peer-to-peer sales.