1. Introduction

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) defines climate change as “a change of climate that is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere…over comparable time periods” [

1] (p. 1). The alterations in the composition of the atmosphere, driven chiefly by the increase in fossil fuel use, have caused the planet’s average surface temperature to rise—a process referred to as global warming [

2]. The term,

climate crisis, is used to emphasize that climate change is the “crisis of our time,” and that the warming effects are “happening even more quickly than we feared” [

3] (p. 1). Since the beginning of data collection in the late 1800s, the hottest years on record have occurred in the last two decades, signaling an increase in frequency and intensity of extreme weather events [

4]. This study is significantly important for the research community and companies struggling with the adaptation of sustainability in their everyday business practices. This study provides theoretical contributions in (a) attending to actionable outcomes related to a company leadership and culture toward change; (b) extending research on the triple bottom line (TBL) by providing a qualitative lens to an area that has largely been quantitatively examined; and (c) extending the work on TBL by noting that the three components do not necessarily overlap but, instead, tend to move fluidly based on what a company deems important. Altogether, this work enhances the lens on environmental sustainability practices implemented by organizations.

According to the United Nations, humanity has 10 years to drastically change how the climate crisis is solved [

5]. At the helm of global warming is fossil fuel use by large businesses [

6,

7,

8]. While the use of stable energy supports economic growth and global dominance, 71% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions since 1988 can be attributed to 100 fossil fuel companies [

6,

9]. Perhaps in response, extreme climate events (e.g., floods, droughts, hurricanes, wildfires, heatwaves, warming of the ocean, and pollution) are heavily influencing decision-making within the transportation industry [

3,

10]. As Hamad has indicated, sustainability is one of the most imperative issues at play with regard to the increasing overpopulation, climate change, pollution, and resource depletion [

11]. While the trucking industry serves as a major participant in the fulfilment of transportation needs, consideration must now be given to the environmental effects and the specific role of the trucking industry in terms of environmental sustainability, as the industry navigates societal expectations and financial outcomes [

12]. Recently, ITS Logistics, a business with a high carbon footprint, adopted sustainability as a core value. This single case study explored how this company with a high fossil fuel use has adapted to the triple bottom line components of social, environmental, and economic sustainability.

2. Literature

2.1. Fossil Fuel Use, Emissions, and the Trucking Industry

As early as 1859, scientists found that certain gases were opaque when released into the atmosphere [

13]. Tyndall executed hundreds of atmospheric experiments to test the relationship between fossil fuel use and opaque emission observations [

14]. Tyndall confirmed that more energy absorption occurs by carbon dioxide and methane with radiant heat [

15]. Additional atmospheric work through observations of invisible infrared radiation led to the discovery of the greenhouse effect [

13]. Greenhouse gases, due to their concentration and abundance of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases, contain heat in the atmosphere and warm the planet’s surface [

16]. With the discovery of GHG, scientific research on how humans exhaust energy through the release of fossil fuels helped advance research on the detrimental effects of global warming [

15].

Extracting fossil fuels (e.g., oil, coal, and natural gas) from the ground and burning the fossil fuels through consumption releases an unprecedented amount of GHG into the atmosphere [

17]. In turn, as these gases warm the planet’s surface, weather events drastically change and increase in intensity, leading to extensive biodiversity loss [

18]. Without global solutions to mitigate the climate change crisis, humans could trigger the next mass extinction event.

As the 20th century unfolded, scientists continued to examine fossil fuel pollution, global warming, and the negative consequences of human activity [

19,

20]. By 1960, the world’s population reached three billion people, leading to an increased demand for fossil fuel use and in turn expanding the damage to the atmosphere inflicted by GHGs [

21]. Increased population growth further increases consumption resources, which also drives energy use. Scientists have advised that population stress with a warming climate could lead to a scarcity of clean air, water, and land [

21]. For instance, Mercer has contended that the West Antarctic ice sheet is vulnerable to the continuing warmth of the surface [

22]. Mercer has reported that ice below sea level would be impacted along with any environmental change that might destroy ice shelves [

22]. These changes to the ice sheet could result in the loss of populated areas, as a sea level rise is predicted in the 21st century [

23].

Scientists expanded their research on global GHGs to include the release of fossil fuels [

24]. Part of the reasoning for this expansion is that fossil fuel use is deeply ingrained in the transportation industry even as global markets grow to include “new technologies, manufacturing methods, materials, information channels, transportation capacity, and trade policies” [

25]. Within the global market, a supply chain, or how goods are moved, is defined as the “network of entities through which material flows” and “encompasses every effort involved in producing and delivering a final product [

26].

Notably, the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals defines logistics as “part of the supply chain process that plans, implements and controls the flow and storage of goods and services between the point of origin” [

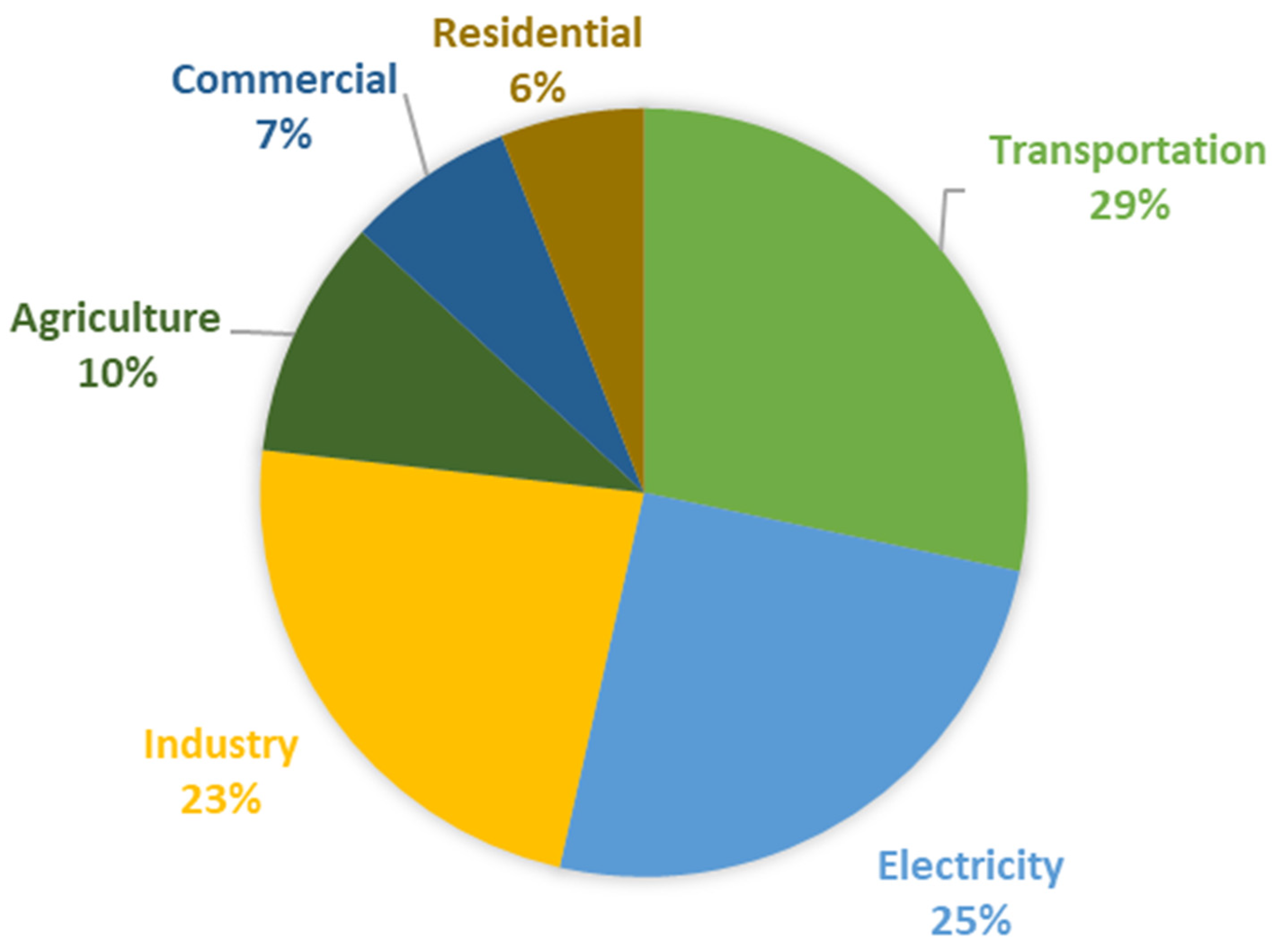

27] (p. 1). In understanding the environmental effects of the supply chain process and logistics within the transportation industry, a 2017 report indicates that transportation accounts for nearly 30% of its total emissions for greenhouse gas in the United States and that this percentage had risen more than any other emissions segment in the previous two decades [

28]. See

Figure 1 for GHG emissions per economic sector.

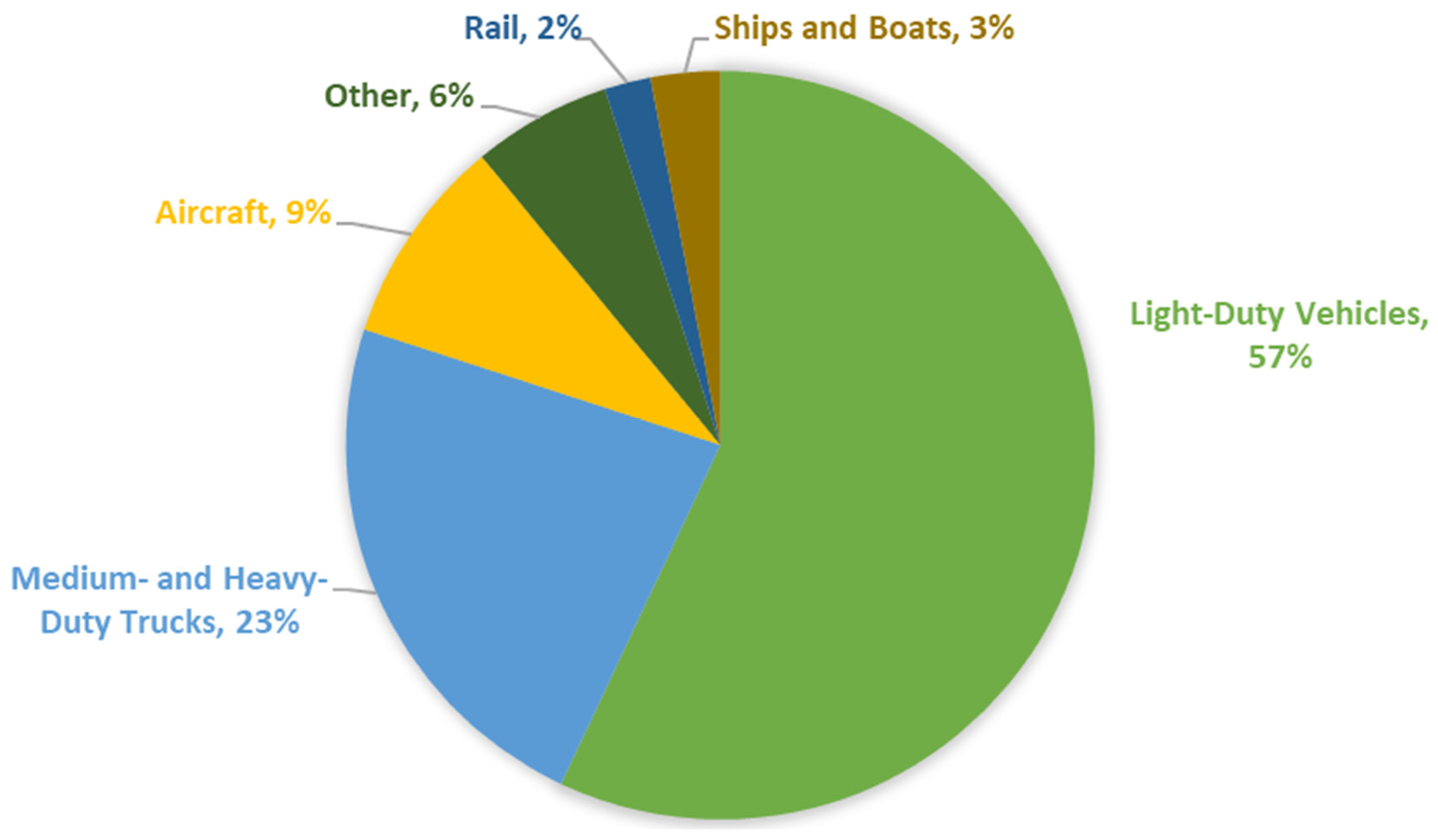

Within the transportation sector, light-duty vehicles accounted for most of the transportation portion (see

Figure 2). Importantly, in 2015, the U.S. logistics industry “moved more than 49.5 million tons of goods worth nearly USD 52.7 billion every day,” as a response to significant demand for goods over long distances [

25] (p. 1). This program also listed heavy-duty trucks as the fastest-growing contributor to U.S. emissions. It is projected that, by 2025, this would account for an additional 23.5% growth, potentially reaching shipments of U.S. goods to 45% [

25].

With the world population anticipated to reach nine billion people by 2050 and energy consumption expected to rise to unprecedented levels, researchers argue that the increased energy consumption will require industries to rethink their fossil fuel use, their contribution to society, and their contribution to biodiversity loss [

31]. With the transport of people and goods continuing to surge, economic growth remains entangled with carbon use and its environmental impacts. Value chains cannot operate without the involvement of the transportation industry to move people and goods. Increasingly, businesses need to find new ways to do business and create new business models, and, though our study was conducted just before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge that this need for new ways was magnified during the pandemic, with major impacts on logistics processes and supply chains [

32]. One model for change that businesses have explored is the triple bottom line, particularly due to calls for reductions in fossil fuel usage. However, few research studies, if any, have explored how companies with high fossil fuel usage incorporate the TBL components. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore how a single company with high fossil fuel usage, ITS Logistics, adapted to the TBL components of social, environmental, and economic sustainability.

2.2. Theoretical Background

This study is situated in the theoretical background related to the TBL, which has increasingly been incorporated by companies when orienting their corporate practices toward environmental sustainability. In alignment with these efforts, corporate social responsibility (CSR) can help guide the vision toward such improvement efforts. As such, the organizational culture also gives grounding to company aspirations with regard to becoming environmentally sustainable. These three areas are discussed in further detail, along with empirical studies related to environmental sustainability through the TBL.

2.2.1. Triple Bottom Line, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Organizational Culture

The TBL magnifies the economic component in traditional accounting frameworks so as to include social and environmental components in business evaluations and operations [

33]. The TBL is often referenced as the three Ps—people, planet, profit—that bring focus to social and environmental impacts, in conjunction with the economic impact throughout the organization’s value chain [

34]. Typically, the social, environmental, and economic components of the TBL overlap to bring forth the area in which optimal business performance and strategic sustainable development occur, as shown in

Figure 3 [

33,

35].

An essential component of the TBL is a focus on environmental sustainability. This refers to when a company works to better understand its unique and specific impacts on the natural environment. As business leaders provide opportunities for employees to become environmentally conscious, adaptable processes are created that meaningfully impact the planet while maintaining dedication to society and stakeholders [

37]. Additionally, if a leader is credible and sincere, there is a greater chance of them being effective at motivating employees so as to help identify sound solutions for company implementation [

37]. Leaders can capitalize on the inundation of competing priorities with resilience to combat environmental scarcity [

38].

As awareness is brought to light, this is further enhanced with attention toward social sustainability, which centers on accountability toward its stakeholders, such as employees, families, customers, suppliers, communities, and any other person influenced or affected by the organization [

39]. Within social sustainability, leaders can invest company resources on a larger scale to support workers’ rights and health, promote diversity and equity, and strengthen safety-related issues. Therefore, stakeholders are affected by organizational activities at many levels [

40]. However, a company must gain public trust, as personal opinions, assumptions, and political affiliation can outweigh scientific research [

41,

42]. To help gain trust, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has released reports to highlight global warming data and its effects on social sustainability [

43].

Global warming reports have also given rise to public attention to environmental sustainability, including public calls for logistics companies to fully consider their energy consumption and contribution to waste and emissions [

44]. In 2019, 3.6 million people across 169 countries protested inaction and pressured leaders among the United Nations, governments, and many companies, such as fossil fuel producers, to address climate change [

45]. Additionally, with 28 countries at various levels of economic development and social sustainability, results demonstrate that social actions can influence change, so a heightened momentum to enact social sustainability has targeted polluting industries [

46,

47]. Leaders who are successful in shifting global economies away from capitalism and resource management have reduced the burning of fossil fuels and decreased waste, while meeting desired growth and community needs [

46,

47]. Centobelli et al. have indicated how businesses can consider environmental sustainability in operations [

48]. They noted that critical cost reductions include financial incentives, energy efficiency, and tax relief. Increases in sales are attributed to an increase in customer demand for sustainable services, improved customer relationships, and the ability of the company and its employees to participate in sustainability programs.

The transportation industry relies heavily on economic vitality as the shipment of goods increases when growth is strong. International trade agreements impact global deliveries that, in turn, impact local progress. Global disagreements between nations can hinder progress in international trade, therefore impacting national companies. For example, Saka has reported that the dispute between China and the United States continues to address an increase in tariffs with potential trade wars and no clear winner, but that what can be observed is a reshaping of the logistics industry that is undergoing constant change [

49]. With an increased focus on government and state regulations, businesses are expected to meet basic business expectations while adhering to forces outside their control. To illustrate, the California Air Resources Board continues to set California’s emissions standards, creating an industry shift to continue business with the state and its port [

50]. Requirements by states with large economies drive change throughout the country and accelerate the expectation that logistics providers comply. With thin margins to support operations, environmentally sustainable practices have shown economic benefits through increased fuel efficiency, incentive programs for drivers, and by promoting technological advances [

44,

48,

51]. In their search for trends to enhance business, the logistics industry has shown that using environmentally sustainable practices results in economic benefits.

Corporate social responsibility, an organization’s vision to responsibly support society’s well-being, is integral to the TBL [

52]. Aguinis has defined CSR as “context-specific organizational action and policy that takes into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance” [

53] (p. 855). Negative impacts on the economic, social, and environmental aspects of TBL through the transportation industry’s depletion of non-renewable sources have been clearly identified (

Table 1), but strategies exist to support each component.

It is suggested that, to develop an effective CSR platform, business leaders cultivate followers who are aware of the need for corporate social responsibility in order to establish processes prior to focusing on the business decisions that impact greater social responsibility practices [

54]. Businesses will typically adopt a CSR platform to address the TBL components. One type of CSR effort involves detailed attention to environmental issues. For example, in consideration of the natural environment, researchers have focused on sustainable transportation through various business topics. When a company focuses on environmentally sustainable transportation through an economic perspective, it is able to serve its customers and support the planet while minimizing its logistics costs [

44]. As a result, sustainability efforts should not lead to tradeoffs among the three areas; rather, a company must find long term strategies to support all three TBL components within the logistics industry [

51].

To embed long-term strategies toward environmental sustainability, a company’s organizational culture becomes an essential aspect of change, which includes an opportunity to enhance the company’s image [

51]. An examination of the organizational culture is a strategy that has been used to identify why U.S. companies might not perform well [

55]. Schein defined organizational culture as “the set of basic assumptions invented, discovered or developed by a particular group, when learning how to deal with problems of external adaptation and internal integration” [

56] (p. 12), aligning the ways in which people think and feel in relation to such problems. In its modern application, a company can have competitive advantage when its culture creates an internal and external form of entrepreneurial-type value that is supportive in such settings [

57]. Confidence grows and ideas are encouraged with a specific focus on innovation, learning, and a future orientation [

57]. Additionally, the culture influences decision-making among leaders by performance through rules and standards, existing support tools, and learning from relationships [

58]. Relationships are considered “one of the strongest mechanisms of how the influence of the organizational culture in the decision-making of a certain company works” [

58] (p. 20). Altogether, the leader impacts the organizational culture with strong implications toward change [

59,

60]. If this change includes sustainability performance, financial capacity also impacts efforts because stakeholders act against environmentally irresponsible companies [

61].

Through an organizational culture, values are foundational and support various degrees of interactions, beliefs, and behaviors shared among members [

62]. These values form through the organization’s history, and different actions are established by dominant leaders. Finally, the organization’s members interpret and make sense of ongoing actions [

62]. Core values are essential to the organization’s identity, with many mission-driven dimensions [

63]. These values enable everyone to function through shared assumptions, with reduced feelings of anxiety or concern, while increasing organizational commitment [

64]. As the trucking industry works to fulfill transportation needs, consideration must now be given to its culture and its values, through the lens of environmental sustainability, in terms of the industry’s attention to societal expectations [

12]. Mahfouz and Muhumed found that there does not need to be a preference for certain values, but that when the values align with whatever type of organizational culture is desired, a business is able to reap positive financial benefits [

65].

2.2.2. Sustainability in Business Practice

Considering the many benefits sought through environmental sustainability, Iqbal et al. explored the influence of sustainable leadership on sustainable performance [

66]. They noted that sustainable leadership keeps the focus on profits but attends to the quality of life for all stakeholders as a priority when implementing the TBL. Their results reveal that sustainable leadership, through organizational learning and empowerment, influences sustainable performance among employees. Marić et al. also found a direct effect of environmental practices on employee commitment, although they did not find a direct link of corporate social responsibility efforts on company performance [

67]. Their study opted to focus on stakeholder theory, with the notion that stakeholders are taken into account with all business actions, and their work acknowledged that the TBL approach harmonizes a synergy of people, planet, and profit in business activities. More specifically, they argued that their link between corporate social responsibility and enhanced employee commitment could, in turn, contribute to long-term company benefits based on numerous related outcomes, like higher productivity, longevity, and job satisfaction.

Empirical studies have consistently identified company benefits with the adoption of environmentally friendly models in their business. For example, Heimerl et al. explored the fashion industry in Malaysia and found that developing countries are adopting environmentally sustainable efforts with textiles [

68]. Whether in developing or developed countries, the companies who adopted environmental sustainability saw higher firm performance over the course of three years than those who did not adopt sustainability practices. They argue that this type of empirical validation can allow others to better understand consumer behaviors as companies manage sustainability. Even from a more inward-facing view, researchers have identified company benefits. For example, Guo et al. found that the adoption of environmental efforts positively influences a company’s internal work regarding innovative practices [

69].

While the aforementioned studies explored company environmental impacts on employees or their company, Agyei et al.’s work centered on customer engagement [

70]. Their work acknowledged that many studies explore company performance, but that the mediating role of customer engagement is of paramount importance with increased marketing demands. They found that companies engaging in environmental practices can yield positive emotional connections with their consumers. Similarly, a study with a more external focus to a company was conducted by Boonsiritomachai and Phonthanukitithaworn, who sought resident perceptions through the TBL approach for sports event tourism [

71]. They highlighted the value in using the TBL for community participation, which was found instrumental in influencing residents’ perceptions toward TBL and tourism impacts.

Positive impacts were also identified by Xu et al., who found that companies who used sustainable practices reduced debt concerns that, in turn, supported long-term financial growth [

72]. Wu et al. similarly considered TBL in tourism by exploring sustainability through residents’ attitudes [

73]. Specific aspects of economic, social, and environmental issues were revealed by residents and the authors affirmed that more qualitative work could identify needs related to company efforts toward environmental sustainability [

73]. Ultimately, environmental sustainability has been deemed a phenomenon that is demanded by customers, which makes it strategically essential if a company is to thrive [

74]. As such, this study was guided by the following research question: How and why did ITS Logistics, a company with high fossil fuel use, adopt sustainability as a core value?

3. Methodology

To explore the research question, a qualitative methodology guided this work using a single case study design with sensemaking. A case study design explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) over time with multiple sources, in-depth data collection, and a detailed case description. The bounded system for this case was ITS Logistics, and the case helped to understand how leaders and employees made sense of environmental sustainability as a core value at the company [

75]. This created an opportunity to focus on employee perspectives and provide context to business activities [

76]. Additionally, sensemaking highlights the ability for a person to understand what is happening and what the event means in a greater context [

77]. Sensemaking helps to shed light on the different meanings held by employees within the context of environmental sustainability [

78]. Therefore, an in-depth examination using publicly available documents, observations, and semi-structured interviews was conducted to explore how ITS Logistics integrated the components of social, environmental, and economic sustainability.

The first data source included publicly available documents. Documents were used to gain a general understanding of the formal aspects of the company. Company documents included its mission, scope of work, and sales information. Documents from competitors were also used to support and clarify data from the observations and interviews. These reports helped determine the economic forces that drive decisions at the company and support data collected during observations and interviews. Annual reports from competitors on their website included environmental reports, standards, and agreements. Other documentation included public information on federal and state legislation and regulations on the industry. Transportation magazines were also obtained for information on pertinent issues and to understand leadership in the industry.

Observations took place at ITS Logistics in the Sparks and Reno, Nevada operations, as they were the locations of the company’s headquarters, warehouse, fleet services, and transportation management divisions. The northern Nevada locations provided the best outlet with which to view the company’s total operation. Observations focused on daily activities in November 2019, the company’s busiest time of year. This enhanced the opportunity to observe a diverse range of company operations, activities, and employee participation in daily tasks. The three-day observation schedule was set by the company’s director of marketing and included the following:

The fleet office, including terminal and driver operations.

The corporate office, including executive leadership, finance, marketing, and sales.

The distribution center, including office, warehouse operations, and customer service.

The integrated national capacity office, including management, sales, and customer service operations.

Field notes were written after observing the sequence and flow of daily operations.

Additionally, face-to-face, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a focus on the following three levels of employees: (a) executive leadership, (b) managers, and (c) hourly employees and drivers. The executive leaders and managers were asked one particular set of questions, and the hourly employees and drivers were asked another. These questions are as follows for the executive leaders and managers:

- (1)

Please indicate what your title is and describe your career journey in attaining this role.

- (2)

How would you describe your company to someone who has never heard of it?

- (3)

What is the one thing about your product/service that you love?

- (4)

On the flipside, is there anything you would change and why?

- (5)

How does your company promote and/or support leadership?

- (6)

What keeps you up at night when thinking about ITS?

- (a)

How would you overcome these concerns?

- (7)

If I were to say “ITS is a very successful company” what is the first thing that comes to your mind? Specifically, how do you define a successful company and why would ITS be included in that definition?

- (8)

Where do you see ITS in 5 years?

- (9)

What outside influences affect operations?

- (10)

What company core values do you best represent in your line of work?

- (11)

Tell me about your organization’s key environmental initiatives.

- (12)

ITS recently added sustainability as a core value. Can you tell me about how that decision came about?

- (13)

How has adding sustainability as core value changed the way you do business?

- (14)

If you had a magic wand, what would you do to achieve the core value of sustainability for ITS?

- (15)

How are strategic decisions made at ITS?

- (a)

Social.

- (b)

Economic.

- (c)

Political.

- (16)

Is environmental sustainability considered when discussing strategy? If yes, then how so?

- (17)

Do you see yourself as an environmental leader? If yes, how so?

- (a)

Environmental initiatives.

- (b)

Actions.

- (c)

Efforts.

- (18)

Do you see monetary savings at ITS with environmental initiatives?

The hourly employees and drivers were asked the following set of interview questions:

- (1)

Please describe your career journey in attaining this role.

- (2)

How would you describe ITS Logistics to someone who has never heard of it?

- (3)

What is your favorite success story from the past 6 months?

- (4)

What is the one thing about your product/service that you love?

- (5)

On the flipside, is there anything you would change and why?

- (6)

What does a great workplace culture look like to you?

- (7)

Under what conditions do you do your very best work?

- (8)

Describe an instance in which you were very concerned about business operations.

- (9)

How does ITS Logistics promote and/or support leadership?

- (10)

How do you perceive power in the leadership roles?

- (a)

How does that influence the way processes/operations/strategy is implemented?

- (b)

What is your role in executing/implementing strategy and development?

- (11)

Can you describe situations where you can make decisions, or change a process?

- (12)

Do you see ITS as an environmental leader? Why or why not?

- (13)

What qualities would you expect an environmental leader to have?

- (14)

Do you see yourself as an environmental leader? If yes, how so?

- (15)

Tell me about your organization’s key environmental initiatives.

- (16)

What do you do here at ITS to support environmentalism?

- (17)

Do you have ideas of how ITS could be more environmentally friendly? Please elaborate if you do.

All communication with participants was conducted one-on-one to protect their privacy. The length of time for the semi-structured interviews was up to one hour and 15 minutes per participant. Additional questions were asked, depending on the pace of the interview or the need for further clarification and prompting. Memos after each interview were written to acknowledge tone, body language, and setting of the interview during questioning. Executives were interviewed first, followed by managers, hourly employees, and the truck driver. The researcher used a professional manner, asked questions with a neutral tone, and rephrased questions for clarification when the question was unclear to the participant. The researchers did not interject feelings, thoughts, or counter arguments in the interview to give participants full control over the interview. Setting the correct tone in the interview enhanced the respect and credibility of the data collection process.

Throughout the interviews, questions, and responses were recorded through the Voice Recorder application on the researcher’s laptop, as well as through the Otter.ai application on the researcher’s cell phone. Both items recorded the entire interview in case an application failed during the interview. Audio recordings were then transcribed, verbatim, through the Otter.ai program and reviewed by the researcher, in full, for transcription accuracy. Once the audio recordings were transcribed, they were kept in the original form on the researcher’s desktop and stored digitally in a secure location.

Notably, environmental concerns were a family topic for the primary researcher of this study when they were growing up. As a native to Lake Tahoe, one of the most pristine lakes in the world, support for pro-environmental behavior became second nature. After completion of their bachelors of science degree in business administration/entrepreneurship, the researcher started an outdoor equipment company committed to building products that closed the loop in manufacturing and created less waste. Throughout the primary researcher’s studies for their master of business administration degree, the researcher explored sustainable actions that industries can employ to remain viable in an environmentally conscious culture. To act and address the business’s relationship to global climate change, the researcher began to advocate for environmental policy and regulations during political campaigns, as well as by attending national climate change training sessions. For over a decade, the primary researcher has built strong expertise in environmental sustainability, with a focus on business operations. The secondary researcher carries the self-perception of being environmentally conscious and values climate change efforts. However, the focus of the secondary researcher is predominantly academic, which was centered on organizational culture and leadership expertise, rather than environmental sustainability. This dynamic among the researchers created an opportunity for expert analysis and reduction of bias across the study. The researchers acknowledge, however, that some level of bias may exist but recognize the value in scholar-practitioner insight and efforts to establish the context for why global climate change is an issue. As such, the researchers aimed to examine only sensemaking principles related to environmental sustainability within the unique company, ITS Logistics.

3.1. The Case

Since 1999, ITS Logistics has been a third-party logistics (3PL) provider on the west coast of the United States. Specifically, ITS Logistics provides supply chain management to businesses seeking to outsource elements of fleet services, fulfillment services, and complete transportation management. Through these three logistics channels, the company is the intermediary between the raw material supplier, the manufacturer, and the retailer. ITS Logistics has over 530 employees for a range of services; 42 employees were in management or executive positions, 125 staff members supported the integrated national capacity division, and 405 staff members supported their dedicated fleet services, distribution services, or were truck drivers. Temporary employees from outside staffing agencies accounted for an additional 50 employees, which doubled in size during the peak holiday season. With its purpose to “improve the quality of life by delivering excellence in everything we do” [

79] (pg. 1), the company brought in over USD 365 million during the time of this study, which was USD 150 million over their anticipated revenue.

ITS Logistics uses 10 core values to guide their work, with the most recent being sustainability. In its pursuit of becoming environmentally sustainable, ITS Logistics boasts a modern fleet of trucks with an average age of fewer than two years or an average of less than three years for trailers. Overall, ITS Logistics’ marketing materials showcase the company as an industry leader in average miles per gallon driven and successful GHG initiatives [

79]. Their newly renovated locations in Nevada are equipped with LED lighting, motion sensors, skylights, 100% low-flow plumbing, air circulation systems, and xeriscaping, alongside a multi-faceted recycling program.

Participants

Participants included three executive leaders, three directors, four managers, three hourly employees, and one truck driver. One employee, a warehouse floor leader, started her career at ITS Logistics two weeks prior to the interview. Being novice to the company, she was excluded from the findings. Executives were selected based on their division of oversight, and additional interviewees were selected by the Director of Marketing or in collaboration with the researcher by random selection of individuals. Because of the public availability of information regarding the executives, and in association with their unique roles in the company, they agreed to have their names used and these are noted below, whereas other participants are noted by title and numerical order (

Table 2).

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection occurred under the auspices of the university’s Institutional Review Board. Three sources of data were used: publicly available documents, semi-structured interviews with 14 participants, and company observations. First, publicly available documents from the ITS Logistics website, competitor websites, and online or print industry news were examined for a general understanding of the organization and operations. Publicly available online documents through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and California Air Resources Board were reviewed, and relevant sales presentations, marketing information, and company figures were provided by the Director of Marketing. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in a one-on-one format, for 10–90 min, upon attaining verbal consent. Written memos acknowledged tone, body language, and the interview setting. ITS Logistics executives were interviewed first, followed by managers, hourly employees, and the truck driver. Finally, observations occurred during the company’s peak season in both northern Nevada locations; these consisted of normal job duties with no interaction with employees. Observations occurred at different times and days over two weeks. Field notes were also written and stored on a ReMarkable tablet as part of the dataset.

The order of the data collection process was important in supporting the data analysis efforts. Document analysis occurred in two phases. The first phase was completed by reviewing websites and highlighting important information. The purpose of this initial analysis was to gain a broad understanding of the company, including its mission, scope of work, sales information, and operations. During the second phase, documents collected after the observations and interviews were examined. During this second phase, the researcher clarified information found during observations and interviews. The field notes described daily settings and experiences. This provided an understanding of how the company operated during peak times with rich descriptions to support the case study.

Data analysis of the transcripts for the 14 interviews was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, transcriptions and memos were read to better understand the content provided and the role and background of each participant. This first phase provided a holistic view of the data. In the second phase, a priori coding was used to segment the data. A priori coding established codes as a template to analyze the data as a “tool for framing data into coherent construct” [

80] (p. 17). A priori coding was used to separate key concepts throughout the transcripts. Transcripts were printed, read, and highlighted with five codes, as follows: (a) the TBL components of social, environmental, and economic sustainability; (b) leadership; (c) core values; (d) economics and growth; and (e) work style and empowerment.

Data from the printed transcripts were then cross-referenced with the electronic copies and highlighted areas were separated into separate documents under the five codes. Keywords, concepts, and explanations helped determine how the themes were identified. Specific interview questions were asked in order to identify core values, culture, and sustainability, leading to a clear analysis of those codes. The identified core values, as indicated by the interviews, were tallied by hand for each executive leader, director, and manager. The top three core values were determined from that list. Data signifying core value concepts were also found through keywords identified in how the core values were described. Content discussed during the interviews were categorized to reflect how environmentally sustainable practices were discussed and what, if any, outside influences (i.e., customers, suppliers, regulations, economy, policy, and community) impacted operations.

3.3. Limitations

ITS Logistics is a trucking company headquartered in northern Nevada. The company has seen sizeable growth in location, team members, and clients within the past five years. However, compared with the worldwide transportation industry, ITS Logistics is a small logistics company with less than a dozen locations to serve its national trucking fleet and warehouse services. Findings cannot be generalized to other carbon-heavy industries or trucking companies. This study cannot address the other sources that are known to contribute to greenhouse gases, such as light-duty passenger vehicles, aircraft, trains, ships, and boats. Importantly, while frontline employees were selected for participation, this was based on availability and random sampling, which may not reflect all experiences or could have introduced bias through the selection process. For example, responses were very positive leaning, which may not reflect the day-to-day realities regarding the pushback, challenges, concerns, or ongoing hesitations that may arise with more trust-building data-seeking efforts that are undertaken over sustained observation periods. However, additional measures to reduce this possible bias were implemented by fostering an open and critical dialogue during the interviews and by verifying interview content through the on-site company observations. This case study represents a snapshot in time and does not explore longitudinal changes at ITS Logistics. As a result, observations and interviews cannot offer a full view of how the company adapts and mitigates climate change concerns, particularly with limited onsite observations.

4. Findings

The observations made on the site of ITS logistics enabled us to situate the case and thus support the triangulation of the findings. While it is recognized that the observations were only a snapshot in time, and which come with limitations, they support the holistic review of the single-case study design. The observations revealed a focused client engagement with its corporate image, insights into the operational infrastructure, and alignment to sustainability practices. When focused on client engagement and the corporate image, both facilities demonstrated an emphasis on projecting a professional and client-oriented environment. At the Sparks location, the lobby was carefully maintained and featured promotional videos detailing ITS’s service offerings. The receptionist exhibited attentiveness and professionalism, creating an impression that the facility routinely accommodates clients and business partners. Leadership accessibility was also emphasized, as members of the executive team—including the Chief Executive Officer, Chief Financial Officer, and Chief Operating Officer—were introduced during the visit. Similarly, the downtown Reno facility placed a strong emphasis on corporate identity and marketing. Branding and promotional murals were prominently displayed throughout sales floors, particularly near conference rooms and elevator areas. Ceiling-mounted monitors continuously broadcast ITS marketing campaigns, industry updates, and sales performance data. These features reinforced a consistent and intentional focus on cultivating brand presence and communicating organizational priorities. With regard to operational infrastructure, the Sparks facility provided direct insight into ITS’s transportation and warehouse operations. Truck drivers were introduced during the tour, and the fleet was prominently displayed. Many trucks carried the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) SmartWay Partner logo, indicating voluntary program affiliation. Vehicles were fitted with aerodynamic side wings designed to reduce drag and improve fuel efficiency. The majority of the fleet appeared recently acquired, and numerous trailers displayed promotional graphics supporting the University of Nevada, Reno football program, underscoring both investment in modern equipment and cultivation of community ties.

Within the warehouse, operations were extensive in scale, with a large square footage and clearly defined client-specific aisles. Active packing areas were observed, in which employees transferred goods from conveyor belts into shipping containers. An orientation session for newly recruited truck drivers was also underway at the time of the visit, highlighting structured onboarding practices. By contrast, the downtown Reno facility primarily housed sales and administrative personnel. Operational activity was centered on office functions rather than logistics, with staff supported by digital infrastructure, including computers and large monitors displaying real-time organizational metrics. Importantly, environmental and sustainability practices were uneven across facilities. At Sparks, recycling bins for cardboard and designated areas for stacked pallets were evident, yet large volumes of plastic wrapping were discarded in general trash bins without a recycling system in place. Moreover, there was no signage or employee-facing communications that suggested the existence of broader sustainability initiatives. Although office space was allocated to the staff member responsible for managing the EPA SmartWay program, that individual was not present at the time of the observation. At the downtown Reno site, sustainability-related practices were minimal. Breakrooms across both floors relied exclusively on disposable dining items, with no reusable alternatives available. Recycling bins were present but ineffective, as materials were not properly sorted. Despite extensive use of branding and marketing imagery throughout the facility, there was no visible signage referencing environmental stewardship or corporate sustainability commitments. The focus on sustainability appeared to remain centered on the macro efforts of the company, given the observational distinctions for the customer who might be walking through the facility, as was the case for these observations.

Indeed, the document review, including website content revealed the broadly encompassing focus of the TBL for company outcomes. For example, on the website’s page the bold emphasis on sustainability speared to reinforce the serious nature of its commitment to the macro-level emphasis on sustainability. For example, the content of sustainability displayed its sustainability term in bright white against a black backdrop (

Figure 4).

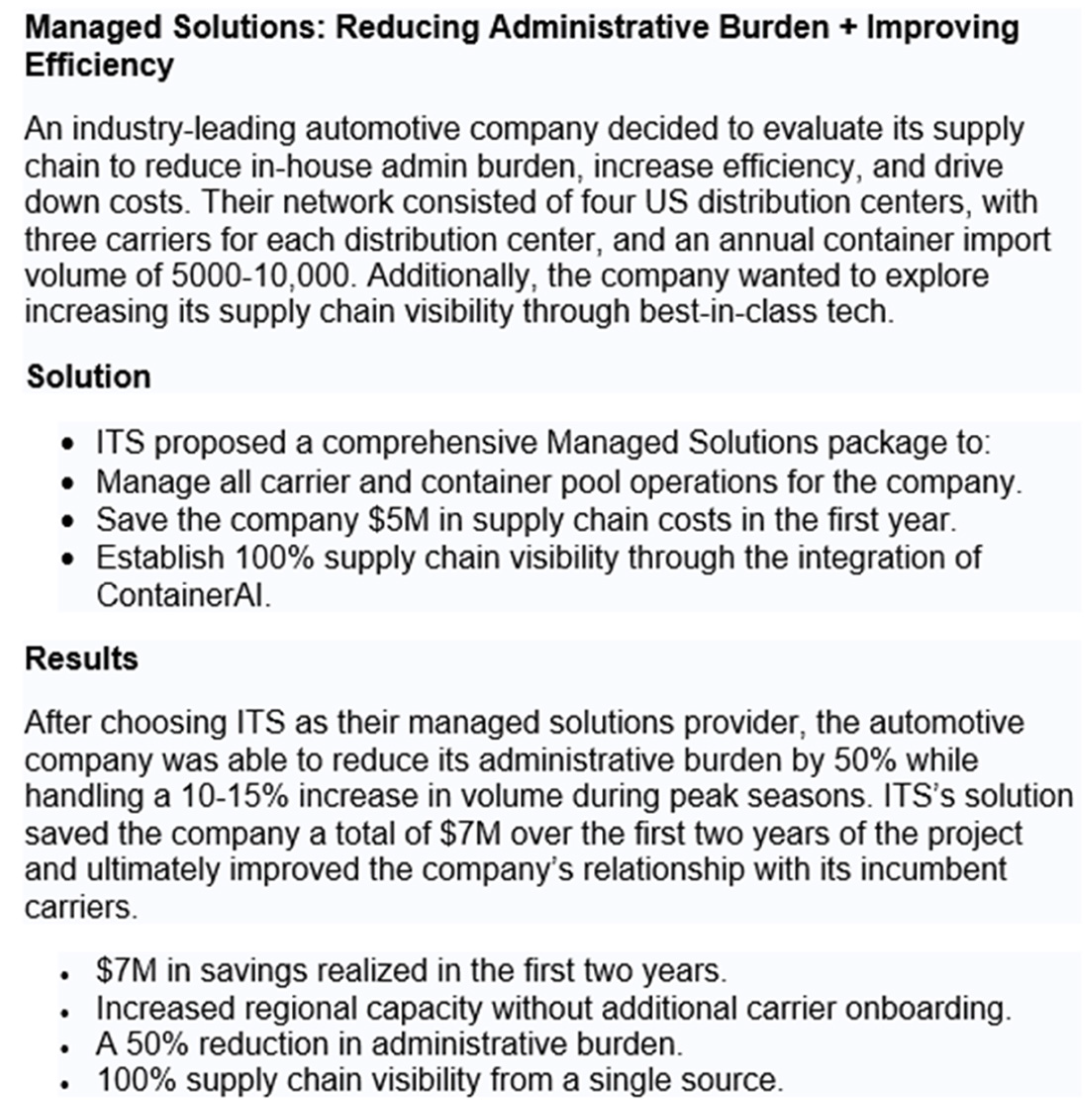

The document analysis also reviewed numerous cases where the company addressed solutions-based efforts around sustainability demands. Some of these were based on their own initiatives and goals, while others were centered on helping to drive solutions for clients that seemed to be addressed in alignment with the company’s efforts around the TBL demands. To illustrate, notes from the publicly available document that synthesize one case study are provided (

Figure 5). The company’s illustrative case study centers on the need, solution, and results.

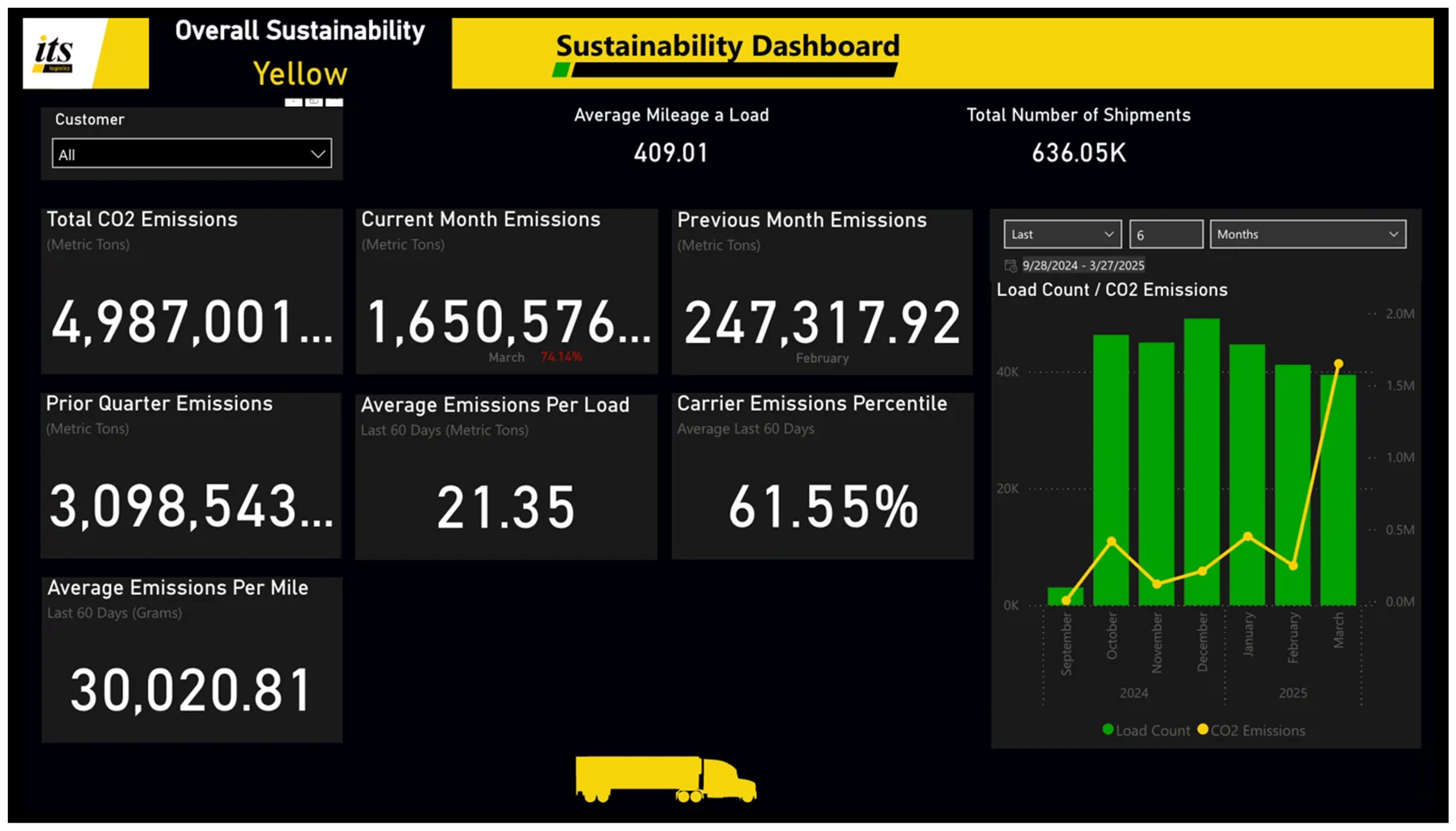

In examining the company’s public-facing tracking of sustainability efforts, their primary data point was focused on carbon dioxide emissions. This includes the total emissions, the quarterly emissions, and the average emissions per mile. Additionally, the monthly emissions, per load emissions, and career emissions percentiles were noted. Finally, a seemingly user-friendly chart also allows website visitors to examine shipment total numbers, and the load count per carbon dioxide emissions, as shown in

Figure 6.

Finally, when triangulating the three data sources of the observations, documents, and interviews, the findings of this case study revealed two themes in response to identifying how and why the company adopted sustainability as a core value. The first theme is centered on leadership, particularly through the company’s historical founding (how). The second theme is centered on the organizational culture contributing to physical and financial growth practices (why).

Table 3 provides an overview of the themes in alignment with the research question that guided this study; this tabular view is intended to help support a visual understanding of the findings.

4.1. Leadership for Strategy and Growth

In examining how ITS Logistics worked to integrate sustainability as a core value, it was evident that leadership matters. Across the many interviews conducted for this study, one constant remark was on discussing the history of the company—participants recounted similar information, like a story. As such, we coined this the history, reflecting the history of ITS Logistics and the employees seeming emphasis on the story-telling efforts in sharing how leadership is a key contributor to environmental sustainability practices.

Leadership was found to be a key theme when participants discussed strategy and growth opportunities. Beginning with its founders, three remain active on committees in the company, and its CEO, Scott Pruneau, intentionally worked to assess the company’s core values to add sustainability as the 10th core value. Supported by company documents, responses from the interviews consistently focused on the long-term sustainability of the company. Two of the TBL components, economic sustainability and social sustainability, were in strong evidence. With the leader as facilitator for growth and change, the founding principles and guiding values appeared to have created opportunities for growth and prompted significant changes in how ITS Logistics executives led the company’s three divisions. With two decades of business in northern Nevada, ITS Logistics grew in profits (economic) and in people (social).

Economic growth was discussed as having occurred through the expansion of national shipping, the incorporation of global goods, and the increased need and acquisition of warehouse space. Participants shared opportunities and struggles with growth, but executives and managers all expressed a role- or division-specific variation of growth. Many participants were specific in stating that ITS Logistics will become a billion-dollar company.

Imbedded in the same belief that growth must be part of ITS Logistics, executives noted challenges toward transformation. Many indicated that ITS Logistics had the right leadership to put expansion in place. However, Ryan shared that leadership was not going to “just plop up a building and move on to the next. We want to be ingrained as much as we can within the community, build up our fleet services, really create a presence within the communities…” The infrastructure for change beyond northern Nevada was described as a struggle due to the nature of the logistics industry and its role in the U.S. economy. Paul Brashier, Director of Intermodal, noted that factors outside the company’s control could determine growth, “it’s going to depend on what the economy does overall. Right? Because we are closely aligned with the ups and downs in the economy.” Even with a future tied to the economy, politics, and consumer behavior, participants exhibited individual confidence that their company would improve.

Leaders also discussed the nature of the logistics industry and the volatility of the economy with adaptability to create new markets and produce a competitive advantage. Even so, it was clear that part of the initial impetus for change was driven by legislative changes leading to stricture regulations. This was in balance with increasing stakeholder accountability, and the desire to gain partnerships with larger market reach, like Patagonia, a company that had affirmed efforts to radically reduce carbon emission through systems changes. As such, in order to gain such partnerships, alignment in values of environmental sustainability needed to exist.

The federal and state government’s role in ITS Logistics’ organizational strategy was shared by many but its director of marketing specifically noted outside factors and influences under consideration:

The biggest one’s legislation. There’s a lot of laws that go into place at either federal or state level that we have to navigate. And that directly affects us in real-time. So, you know, take for instance AB5 that just went to the California legislature. That has a big impact on the folks that we contract out the work for us. Anytime that the Department of Transportation in DC implements e-logs or hours of service requirements or clean, you know, truck requirements, that affects us.

In all, participants shared in a sense of pride, admiration, and optimism regarding personal and organizational growth. However, they shared this sense of excitement with a sense of trepidation regarding the economic vitality and the meeting of environmental compliances alongside standards and industry practices.

The trepidations, however, appeared to be navigated by the leaders’ intentionality in hiring the right people for the appropriate positions. This strategy was described as leaders being able “put the right people in the right place, and they’re going to do whatever they can to support those people” (Manager #3). Indeed, many executives described a long courtship with the founders when detailing their interview process to ensure hiring processes not only supported longevity but also company performance outcomes. For example, during one company observation, it was clear that this intentional leadership effort allowed for employee risk-taking and innovation as employees shared ideas with the CEO using current client examples. After the observation, interviews confirmed the power and influence executives appeared to have and use for long-term vitality. As CEO, Scott shared, “it’s just making sure you act, you’re disciplined enough to act according to your values all the time.” Comments from all levels of participants focused on the legacy of the founders, support from senior leaders, and the competitive atmosphere upon which ITS Logistics was built.

This meant that at all levels, there was a clear understanding of structured leadership efforts and systems of support. Additionally, with a structured leadership team, executives commented that strategic decisions would be impossible without a strong team of managers, employees, and truck drivers. Notably, 11 of 14 participants began their career at ITS Logistics in a lower position than during the time of this study, all of whom spoke highly of their promotional pathways and future possibilities. The other three participants were able to describe opportunities available for others, and their personal aspirations for growth in the future, and employees in all three divisions (i.e., fleet, distribution, and brokerage) said they could enhance their work through pay-based skill development, cross-training, and leadership programs. Mike Crawford, President of the Integrated National Capacity division, explained that supporting his staff meant everything to him when describing the long-term, internal leadership, and development of others. Altogether, aspirations were discussed in terms of social sustainability, such as personal growth, team performance, and individual goals.

4.2. Organizational Culture as Family

Motivation from senior leadership to keep the company’s core values intact and maintain the organizational culture played a significant role in the physical and financial growth at ITS Logistics. Eight participants, in particular, directly used the term family to describe the culture of ITS Logistics. Ownership of the company’s culture, its role in their employee’s lives, and among the community were thoroughly discussed by senior leaders, directors, and managers. The culture built by the three founders clearly defined company practices to care for its employees and community. To poise the company for growth, ITS Logistics strategically created leadership opportunities that fit within the established values. Specific goals included doubling the size of employees from 500 to 1000, expanding its building facilities, having operations east of the Mississippi River, and seeking to donate one-quarter of a million dollars locally. As such, this culture was also driven by a deep connection to the local area. The emphasis on the connection to the geographical area helped to further reinforce a sense of family throughout the company practices.

The sense of family presented itself as a reason why candidates wanted to work for ITS Logistics, and why employees believed they had found a career there. Employees specifically remarked on the benefits to providing input on decisions by being able to access all employees and the company’s leaders. As such, the family culture was strongly situated within the company’s decision-making efforts, which appeared to increase everyone’s ownership of the company’s performance.

Through this ownership, employees also took stakeholder considerations into account. The use of stakeholder considerations created a direct bridge between the company and its positive relationships with customers. Specifically, interview data revealed that desired success for the company focused beyond internal employee relationships. Beyond the internal relationships, long-term connections with suppliers, customers, and the community were described as helping ITS Logistics improve sales and operations against competitors. Participants spoke of the company’s long-term strategy built on its relationship with customers and which tied back to the organizational culture. As one leader noted, “the culture itself leads to being invested in what you’re doing and working hard for the company” (Patrick).

The organizational culture helped to solidify the why for creating change toward environmental sustainability. The bottom-up approach in its decision-making meant the company was very interactive, valued opinions from all levels, and incorporated decision-making efforts beyond executives. Appropriate, autonomous decision-making was also remarked as energetic and supportive of the family-oriented culture. Employees expressed being supported in their ideas and decisions, and some of them even discussed scenarios in which decisions had to be made in the middle of the night, thousands of miles away from its headquarters, and without the help of the customer service department.

Aspirations to be the best at their job, to contribute positively to the culture, and develop others, were frequently discussed during the interviews with employees. The culture also played a significant part in how participants described their work conditions, goals, and their understanding of leadership. Thus, success was highlighted by ability to do what is right by the company through the extension of its family values beyond desks and building walls of ITS Logistics.

Environmental Sustainability

In 2018, ITS Logistics added sustainability to its core values as part of its organizational culture. To understand the role of core values in the work lives of participants, specific attention was placed on to how core values were described. Executives were aware of their impact on the company and its employees in relation to the 10 established core values. Participants at each level described the support they received to successfully navigate the established core values. Each interviewee also showed respect around the discussion of core values and could describe the value that best fit their work and personal values in depth. Responsibility to ensure that employees live, work, and act according to the core values falls on the company’s leaders and mentors. Additionally, as participants discussed the way in which a key leader was let go for not meeting the expectations of the core values, it was clear that the preservation of long-term leadership was not always successful. While employees and truck drivers were not expected to exhibit all of the core values, leaders were expected to act in accordance with the values at all times and appeared in discussions of physical company growth. Participants even described the process of executive leaders coming together to evaluate what ITS Logistics stood for, including changing the image used to describe the initiatives. Paul shared, “it wasn’t like, you know, Moses, and came down from on high with the stone tablets and everybody will march to these orders. There was a lot of collaboration, ground level, all the way up, to what those were.”

The 10 core values (i.e., safety first, integrity, respect, teamwork, compassion, quality, continuous improvement, having fun, results, and sustainability) were prominently featured in offices, at employee’s desks, and displayed on the walls on the brokerage floor.

Figure 7 demonstrates the sustainability core value. Interview data revealed that employees focused on some of the values more than others. For example, the core value most cited in the interviews was teamwork; this was followed by having fun, and integrity. Each participant was asked specifically about sustainability as a core value, which was visually added to the list of core values with an imagery featuring a cupped hand, holding a newly sprouted plant. Along with the imagery, the accompanying tag line for sustainability read “Driving towards a cleaner future” [

79]. Spurred by inspiration from living and working in the local area, several interviewees remarked on their respect for companies with like-minded environmental efforts to aspire and emulate.

Leaders described the way in which sustainability was adopted as a core value because awareness was the first step toward environmentally sustainable growth. The literal inclusion into their known core values was not just seen as an opportunity for awareness, but it could also be used to leverage accountability and employee practices in this effort. Uniquely, although this core value was deemed important among its leaders, it was also the core value that most participants struggled to define, implement, and measure. Even so, a belief in the potential for a better quality of life was reflected across participant interviews and demonstrated a strong awareness about sustainability. When discussing how the company was a good steward in the community, leaders remarked that they saw employment, benefits, and a path for career betterment as meeting the expectations of the core value, so they were more specific in identifying measurable outcomes of environmental sustainability. Interviews also referred to community involvement through monetary and time donations. Several participants, in discussing the continuation of socially sustainable efforts toward company growth were able to elaborate ideas with clear familiarity.

In consideration of the social element in sustainability, ITS Logistics was described as a stable and actionable company. However, environmentally sustainable efforts due to concentrated and deliberate actions were stated as a personal concern. As shown in other aspects of the company, several participants noted the desire to be the best environmentally sustainable company in the industry. For example, there was a shared belief around the core value of sustainability that allowed them the right to tout their successes in terms of the company’s ability to navigate environmental efforts mandated by the EPA and the California Air Resources Board. Managers from the fleet and brokerage divisions saw this as the chance to fit it, gain market share, and enhance day-to-day operations. Additionally, in the effort to define what sustainability means to ITS Logistics, its employees, and the community, only a few participants struggled to define environmental sustainability and their role in the integration of the sustainability as a core value. For the most part, participants indicated that the company would be successful in its efforts because of the successful track record shown with the previously existing core values, even if the intended traction for the core value of sustainability was not at optimal levels.

The motivation toward the attainment of the optimal levels to be environmentally sustainable was shared across company employees. First, many participants, including the truck driver, commented on the compliance to industry standards set by competitors, the EPA, and state legislatures. Second, ITS Logistics adopted a monetary incentive program for truck drivers to recognize efficient driving and increase the miles per gallon attained by the trucks. Several senior executives, directors, managers, and the truck driver described how this program began as a means to save the company money through fuel costs, but that positive impacts towards the environment were realized with the increased efficiency. Third, the assets the company leases are newer and have shorter contracts, which has allowed the company to use the latest technology with environmental features. Citing that environmental sustainability was bigger than one person, or even one company, those at ITS Logistics clearly described these actions as positive and dedicated their efforts to work toward environmental sustainability.

5. Discussion

The literature reflects a plethora of quantitative studies in which factors are examined in relation to the TBL and desired company outcomes. However, there is only a dearth of studies that provide a qualitive lens into how and why leaders opt to integrate environmental sustainability into their companies. Khan has argued that companies cannot simply attend to profit-only endeavors but must consider the TBL approach for long-term survival and success [

74]. The most notable qualitative findings of this study center on the role of leadership and the importance of a strong organizational culture, both of which reinforce quantitatively explored factors associated with the TBL.

Tied to the role of leadership, this qualitative single case study of ITS Logistics demonstrated that a company’s history can continue to play a critical role in establishing processes and expectations towards its trajectory of success. The history of ITS Logistics appeared to be fundamental to its long-term strategy; their shared story was clearly intertwined with the company’s current leaders. As Iqbal et al. affirmed, contextual factors are important, and, in the case of this work, the history and leadership mattered [

66]. Additionally, when leadership was described by the participants at ITS Logistics, they indicated that leaders acted as role-models for their employees. This mirrors the way in which leaders can ask of other employees only that which they are willing to do themselves [

81,

82]. Importantly, this qualitative work brings to light the significance of sustainable leadership, but with an opportunity to examine it in action [

66]. Sustainable leadership requires the leader to promote sustainable practices across all levels of the organization, as was evidenced in the present study [

66]. In exploring this through an international perspective, the leaders’ actions can be considered as aspects tied to social duty or intergenerational responsibility. This attends more to collectivist perspectives that can help shape new insights that do not merely focus on Western-style values. Consensus building may be approached differently through an increased sense of loyalty, rather than a more top-down hierarchical approach. In doing so, attention to cultural traditions and collectivism could still contribute to desired storytelling and organizational cultural ties that help empower members and support overall performance outcomes and goals. Additionally, international endeavors may attend to company values and environmental sustainability to drive cost-saving initiatives by also tying those values to already-existing collectivists beliefs, such as respect for nature, communal ethic, or spiritual beliefs. These relevant distinctions can help address differing meanings and sense-making efforts that are designed to embed environmental sustainability as a core value whereby the company metrics may not necessarily be the prominent driving force for change in the TBL.

The leaders at ITS Logistics were instrumental in establishing a need and guiding a vision toward environmental sustainability. The company’s current leaders were described as upholding values that were linked to the company’s culture, with concrete practices to support employee development, guide customer service, and grow. They allowed their employees to make decisions and resolve issues, which also reiterates alignment with sustainable leadership and problem solving [

83]. Nevertheless, challenges can contribute to full adoption of the TBL. For example, in this case study, leaders were often focused on the broader goals by which to meet legislative demands, stakeholder expectations, and the company’s economic growth. However, among employees, a disconnect was often indicated, supported by the interviews and observations, whereby smaller actions toward environmental sustainability were still needed within the company. For example, break room supplies often had single-use items, or recyclable materials were often an afterthought. This created a difficult barrier in both communication and action. The employees knew the vision included the core value of environmental sustainability, but this came at odds with those small but impactful changes that they wanted to incorporate from a day-to-day perspective. Thus, these views and alignment with action cannot be understated with the leadership’s efforts to fully implement change across the company’s operations. Through the sense-making exploration, employees selectively interpreted the specific meaning of environmental sustainability from the fuel-saving incentive program, and how they retained this concept of sustainability, which is linked to economic benefits, through interactions within the family-feel culture within the organization. As such, the varying positional roles and power dynamics within the organization contributed to individual sensemaking distinctions across the company’s aims to embed environmental sustainability as a core value within the organizational culture.

Through its organizational culture, ITS Logistics demonstrated an investment in its employees and increased customer support beyond industry standards. These practices seemed to have improved as the newly appointed executive leaders supported the established culture and integrated their own expectations to the existing company values. The ITS Logistics’ leaders work in this regard reflected a form of cultural synergy and respect, as described by Costache et al., particularly as the leaders provided opportunities to embrace and improve upon the company’s core values [

57]. This form of organizational culture allows for capacity-building among its individuals in order to enhance learning and support overall company growth [

84].

Marchisotti et al. have emphasized that executive leaders could directly impact employee development and add strength to decision-making processes based on their relationships with peers [

58]. Employee development, decision-making, and relationships were similarly described within the organizational culture, the expansion of the core values, and the execution of the company strategy at ITS Logistics. Employees shared their personal views of the influential individuals in leadership roles, often referencing a family-oriented culture as a defining characteristic at ITS Logistics, all of which were consistent with the literature. Ultimately, all stakeholders appeared to be reaping the benefits of environmental sustainability, as discussed by Marić et al. and Guo et al., whose work has identified numerous internal benefits to a company [

67,

69]. As company leaders continue to seek concrete benefits, it is essential to highlight that sustainable leadership is still in the infancy stage, so that these qualitative findings can support the examination of leaders’ actions toward environmental sustainability [

85].

5.1. Use of the Triple Bottom Line

Centered on the TBL approach, environmental sustainability had not quite risen to the level of being a shared value among its members. For example, the term sustainability could not be clearly defined by executives and managers, nor could they indicate what it meant to the company, its employees, and the community. Nevertheless, sustainability was most frequently described as a means to incentivize economic growth, and it reflected a personal value with a direct connection to the local geography and its nature, along with an aspiration to the goals of environmentally sustainable companies.

The areas of social, environmental, and economic sustainability are complex topics to examine, especially when each must function harmoniously [

67]. Furthermore, the interactions between the TBL components within a business are difficult to articulate, but the complexity of this study and an effort to visually depict the TBL approach at ITS Logistics are demonstrated in

Figure 8. Our findings enhance existing theory in this area as we observed that the three TBL components do not completely overlap but, instead, move fluidly based on what company leaders deem important. In an organizational culture characterized by strong networks of relationships, social sustainability is a prerequisite for achieving economic sustainability. For industries with thin profit margins, economic benefits are the primary driving force for companies to adopt environmental practices that go beyond compliance requirements. Ultimately, when the foundational drivers differ, the fluidity of the TBL changes. It is as though existing antecedents within the company create a broader focus on one of the TBL components, even if all three are contributing factors to the overall model of people, planet, and profit. Certainly, Litman and Burwell have cautioned that trade-offs among the three components should not occur [

51]. At ITS Logistics, the focus on the TBL components appears to have begun with its people, as the social aspect was entangled with the family-oriented culture, employee development, customer relations, and an effort to attend to all stakeholder needs. The positive impact of the workforce was referenced at all levels, but economic outcomes remained a consistent goal, which confirmed the need for the alignment of values with organizational culture [

65,

86].

Findings suggest that the success of its people was perceived to strengthen the company’s profits and economic capabilities. The participants’ desires to maintain operations and grow were dependent on their ability to leverage the economic benefits, with data presenting economic sustainability to implement environmental actions. These actions were listed as being highly dependent on environmental regulations, a healthy society, fuel efficiency, and a viable fleet, all of which were seen as an economic advantage when accounting for environmental benefits [

46,

47,

87]. Sustainability as a core value supported the commitment ITS Logistics has made toward the environment through cost-saving measures. As ITS Logistics leveraged its economic benefits toward environmental sustainability, as similarly identified by Xu, sustainability as its core value became the next logical action for the company [

72].

This work is important to consider in comparison to other recent efforts. For example, Pham et al. have found that corporate values do contribute to positive employee performance [

88], thus supporting a more fluid process of the TBL, one for which the social component reflects a stronger linkage to the economic aspect and which in turn contributes to the initially intended environmental impacts through company operations. In the quantitative findings by Pham et al., employee beliefs were critical to building trust, and this was in alignment with the leadership style of the corporation. Their cohesion functioned to establish opportunities to guide the creation of core values that could be integrated into the ongoing organizational culture [

88]. This was similarly reaffirmed in the work by Kwok et al., whose results identified two critical factors supporting the implementation of values that supported corporate sustainability [

89]. Specifically, Kwon et al.’s focus on the factor of empowering the business process management can be seen as the organizational culture of the functions within the company, while the customer-centric excellence can be likened to the TBL emphasis on people, achieved through stakeholder-driven demands [

89]. In their quantitative analyses, these factors remained interlaced with a third factor of sustainable progress, all of which was in alignment with efforts toward the bottom line of economic performance. The findings of the current study provide qualitative insight into these past quantitative analyses, and ongoing qualitative endeavors similarly note the responsibility of the leader and the corporation’s history, evolution, and vision in creating new directions for progress and sustainability. To illustrate, Kantabutra explored the unique relationship among company values toward sustainability through leadership vision [

90]. Ultimately, the vision must include clarity, imagery, and performance indicators that can be communicated effectively across the company’s numerous channels for long-term opportunities that drive environmental sustainability. ITS Logistics’ efforts to navigate interstate regulations, particularly California’s stringent emissions standards, demonstrate the critical role of environmental regulation in driving firms’ transition to sustainable growth, a phenomenon also confirmed in broader macroeconomic research [

91].

5.2. Macro-Level Sustainability