Paving the Way to Success: Linking the Strategic Ecosystem of Entrepreneurial Start-Ups with Market Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

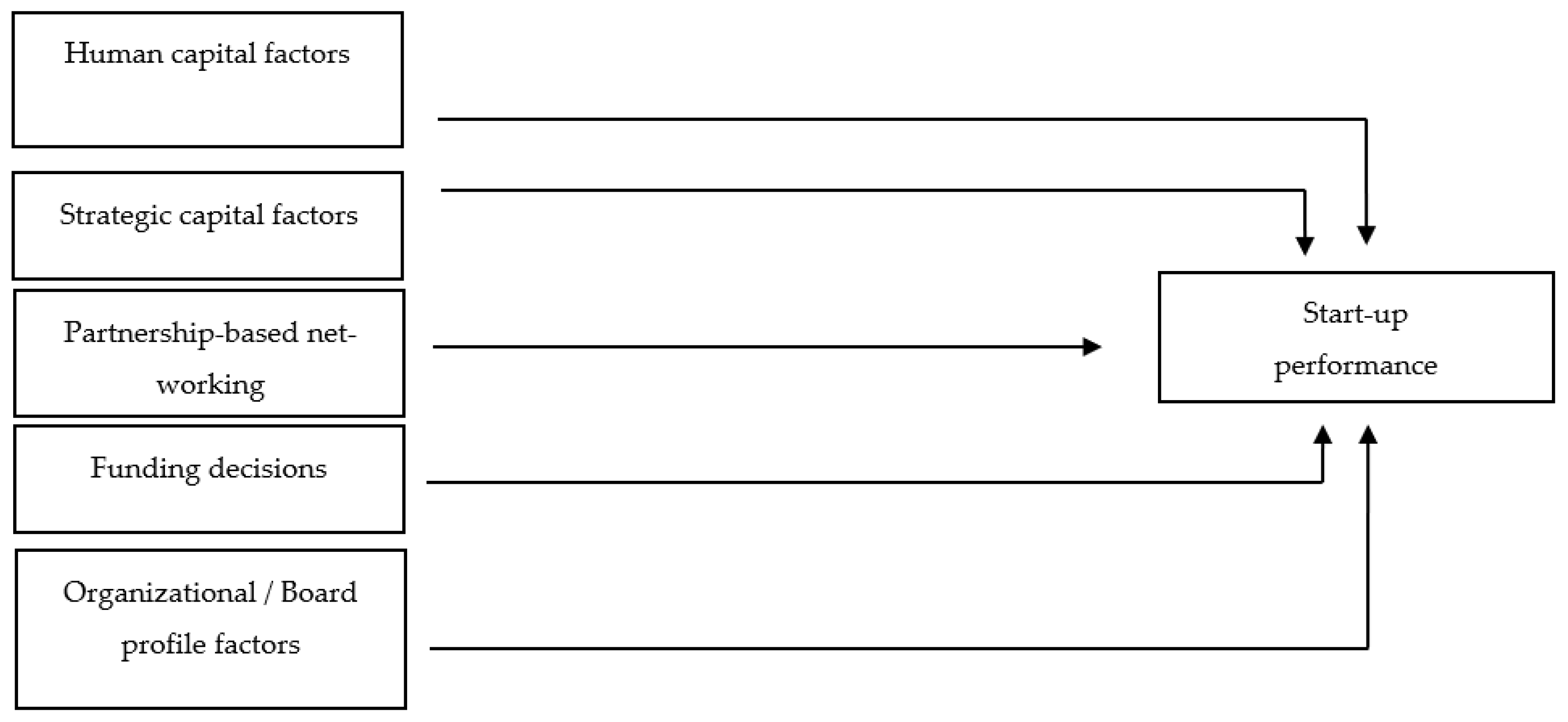

2. Theoretical Underpinnings of the Study and Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Survey Instrument

3.4. Variables

3.5. Assessing Validity and Reliability

4. Findings and Discussion

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahieu, J.; Melillo, F.; Thompson, P. The Long-Term Consequences of Entrepreneurship: Earnings Trajectories of Former Entrepreneurs. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricopoaia, O.; Lupașc, A.; Mihai, I.O. Implications of Innovative Strategies for Sustainable Entrepreneurship—Solutions to Combat Climate Change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkua, T.; Heijman, W.; Benešová, I.; Krivko, M. Entrepreneurship as a Driver of Economic Development. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2025, 13, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, K.; Telukdarie, A.; Philbin, S.P. Digital Start-Up Ecosystems: A Systematic Literature Review and Model Development for South Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Souitaris, V.; Gruber, M. Creating New Ventures: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Li, J.; Liang, B.; Yan, Z. Optimizing Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: The Role of Government-Certified Incubators in Early-Stage Financing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpysa, J.; Singh, U.; Singh, S. Validation of Decision Criteria and Determining Factors Importance in Advocating for Sustainability of Entrepreneurial Startups Towards Social Inclusion and Capacity Building. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirolo, L.; Presutti, M. The Impact of Social Capital on the Start-Ups’ Performance Growth. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthensteiner, V.; Leitner, K.H. The Role of Human and Financial Capital in the Business Model Design-Performance Relationship: Evidence from Austrian Start-Ups. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Bauerschmidt, A.; Hofer, C.W. The Determinants of New Venture Performance: An Extended Model. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1998, 23, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortega, M.J.; Parra-Requena, G.; Garcia-Villaverde, P.M.; Rodrigo-Alarcón, J. Understanding the Success of Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Dynamics of the Relationships between Strategic Sustainability and the Company. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2025, 31, 1869–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Campbell, B.A.; Franco, A.M.; Ganco, M. What Do I Take with Me? The Mediating Effect of Spin-Out Team Size and Tenure on the Founder–Firm Performance Relationship. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1060–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tula, S.T.; Ofodile, O.C.; Okoye, C.C.; Nifise, A.O.A.; Odeyemi, O. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in the USA: A Comparative Review with European Models. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Khanna, A. A Systematic Literature Review of Startup Survival and Future Research Agenda. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2023, 26, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Grilli, L. Founders’ Human Capital and the Growth of New Technology-Based Firms: A Competence-Based View. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landqvist, M.; Lind, F. A Start-Up Embedding in Three Business Network Settings—A Matter of Resource Combining. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 80, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, R.E.; Petersen, B.C. Capital Market Imperfections, High-Tech Investment, and New Equity Financing. Econ. J. 2002, 112, F54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, M. Sustainable finance: An overview of ESG in the financial markets. In Sustainable Finance in Europe: Corporate Governance, Financial Stability and Financial Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 465–504. [Google Scholar]

- Zairis, G.; Liargovas, P.; Apostolopoulos, N. Sustainable finance and ESG importance: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Schnatterly, K.; Hill, A.D. Board Composition Beyond Independence: Social Capital, Human Capital, and Demographics. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 232–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Roh, T.; Kim, J.; Park, S.; Bae, Y. Unpacking sustainability in start-ups: A systematic review and research agenda. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argaw, Y.M.; Liu, Y. The Pathway to Startup Success: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Critical Factors and the Future Research Agenda in Developed and Emerging Markets. Systems 2024, 12, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryadita, H.; Sukoco, B.M.; Lyver, M. Founders and the Success of Start-Ups: An Integrative Review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2284451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.M.; Storz, C.; Held, L. Whom Do Nascent Ventures Search For? Resource Scarcity and Linkage Formation Activities during New Product Development Processes. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seet, P.-S.; Lindsay, N.; Kropp, F. Understanding Early-Stage Firm Performance: The Explanatory Role of Individual and Firm Level Factors. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 42, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotopoulos, I.; Kontolaimou, A.; Tsakanikas, A. Antecedents of Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship Before and During the Greek Economic Crisis. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 24, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J. Social Safety Nets and New Venture Performance: The Role of Employee Access to Paid Family Leave Benefits. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 2545–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.E.; Dowling, M.J.; Megginson, W.L. Cooperative Strategy and New Venture Performance: The Role of Business Strategy and Management Experience. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business Model Design and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Firms. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.W.; Lee, Y.H. Effects of Internal and External Factors on Business Performance of Start-Ups in South Korea: The Engine of New Market Dynamics. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 1847979018824231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Podoynitsyna, K.; Van Der Bij, H.; Halman, J.I. Success factors in new ventures: A meta-analysis. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Simeone, A.; Sirén, C.; Antretter, T. New venture survival: A review and extension. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 378–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Frijat, Y.S.; Elamer, A.A. Human Capital Efficiency, Corporate Sustainability, and Performance: Evidence from Emerging Economies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital; National Bureau of Economic Research: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer, J. Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution. J. Political Econ. 1958, 66, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, K.N.; Thai, Q.H. Entrepreneurial Competencies—A Systematic Literature Review. J. Int. Entrep. 2025, 23, 54–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D. Towards a Qualitative Understanding of Human Capital in Entrepreneurship Research. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, R.; Karaöz, M.; Mendonça, J. The Impact of Human Capital on the Early Success of Necessity versus Opportunity-Based Entrepreneurs. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winne, S.; Sels, L. Interrelationships between Human Capital, HRM and Innovation in Belgian Start-Ups Aiming at an Innovation Strategy. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1860–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B. Discovery and Creation: Alternative Theories of Entrepreneurial Action. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvel, M.R. Human Capital and Search-Based Discovery: A Study of High-Tech Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.W.; McMullen, J.S.; Artz, K.; Simiyu, E.M. Capital Is Not Enough: Innovation in Developing Economies. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 684–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.C.; Neck, H.M.; DeTienne, D.R. How Corporate Entrepreneurs Learn from Fledgling Innovation Initiatives: Cognition and the Development of a Termination Script. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 829–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criaco, G.; Minola, T.; Migliorini, P.; Serarols-Tarrés, C. ‘To Have and Have Not’: Founders’ Human Capital and University Start-Up Survival. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 567–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvel, M.R.; Davis, J.L.; Sproul, C.R. Human Capital and Entrepreneurship Research: A Critical Review and Future Directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G.; Murtinu, S. Entrepreneurial Judgment, Uncertainty, and Resource Mobilization. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, K.; Pennings, J.M. Internal Capabilities, External Networks, and Performance: A Study on Technology-Based Ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 615–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaarani, K.A. The Role of Strategic Implementation in Improving Startups’ Performance. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 2018, p. 16730. [Google Scholar]

- Symeonidou, N.; Nicolaou, N. Resource Orchestration in Start-Ups: Synchronizing Human Capital Investment, Leveraging Strategy and Founder Start-Up Experience. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 194–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Guo, A.; Ma, H. Inside the Black Box: How Business Model Innovation Contributes to Digital Start-Up Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, B.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Pugliese, R.; Tracogna, A. Business Model Evolution, Contextual Ambidexterity and the Growth Performance of High-Tech Start-Ups. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Autio, E.; Szerb, L. National Systems of Entrepreneurship: Measurement Issues and Policy Implications. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Colombelli, A.; Grilli, L.; Minola, T.; Rasmussen, E. Innovative Start-Ups and Policy Initiatives. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 104027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcombe, A.L. Social Structure and Organizations. In Handbook of Organizations; March, J.G., Ed.; Rand-McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965; pp. 142–193. [Google Scholar]

- Okamuro, H.; Kato, M.; Honjo, Y. Determinants of R&D Cooperation in Japanese Start-Ups. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasti, M.; Garousi Mokhtarzadeh, N.; Jafarpanah, I. Networking Capability: A Systematic Review of Literature and Future Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.N.; Norrman, C. Incubator Best Practice: A Framework. Technovation 2008, 28, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, C.; Dowling, M.; Welpe, I.M. Firm Networks and Firm Development: The Role of the Relational Mix. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 514–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; Mion, G.; Vigolo, V.; De Crescenzo, V. Business Incubators as a Driver of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Development: Evidence from the Italian Experience. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2025, 31, 1430–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, M.; Zouhar, J. The Causes of Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Discontinuance. Prague Econ. Pap. 2016, 2016, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, M.; Longo, M.C.; Zouhar, J. Do Business Incubators Really Enhance Entrepreneurial Growth? Evidence from a Large Sample of Innovative Italian Start-Ups. Technovation 2018, 82, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooampon, S. Fundamentals of Managing Technology Ventures; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, A.; Auer, M.; Ritter, T. The Impact of Network Capabilities and Entrepreneurial Orientation on University Spin-Off Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichail, G.; Carayannis, E.G. Beyond Funding Shortages: A Longitudinal Analysis of Causal Shifts in Academic Start-Up Failure. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, J.T.; Shane, S.; Delmar, F. Multistage Selection and the Financing of New Ventures. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Auken, H.; Neeley, L. Evidence of Bootstrap Financing among Small Startup Firms. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Financ. 1996, 5, 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, T.W.; Possani, E. Investment and Operational Decisions for Start-up Companies: A Game Theory and Markov Decision Process Approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 299, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Rutherford, M.W.; Pollack, J.M. An Exploratory Meta-Analysis of the Nomological Network of Bootstrapping in SMEs. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2017, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Blick, T.; Paeleman, I.; Laveren, E. Financing Constraints and SME Growth: The Suppression Effect of Cost-Saving Management Innovations. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 62, 961–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.N.; Udell, G.F. A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. J. Bank. Financ. 2006, 30, 2945–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P.; Lerner, J. The venture capital revolution. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwienbacher, A. A Theoretical Analysis of Optimal Financing Strategies for Different Types of Capital-Constrained Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 753–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Grilli, L. Funding gaps? Access to bank loans by high-tech start-ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 29, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. Delegated Monitoring and Financial Intermediation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1984, 51, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1939; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, Q.; Karpoff, J.M. The trust triangle: Laws, reputation, and culture in empirical finance research. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.; Martinez, M. Strategic Risk Management in Financial Management: A Review of Concepts, Frameworks, and Practices. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Owen, R.; Scott, J.M.; Lyon, F. Financing green innovation startups: A systematic literature review on early-stage SME funding. Ventur. Cap. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, D.; Yu, J.; Zhong, R. The limits of green finance: A survey of literature in the context of green bonds and green loans. Sustainability 2021, 13, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate green bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, A.M.; Robinson, D.T. The Capital Structure Decisions of New Firms. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.A.; Sokolyk, T. Debt Financing, Survival, and Growth of Start-Up Firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 50, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.W.; Dybvig, P.H. Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity. J. Political Econ. 1983, 91, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J.; Rezepa, S.; Zatrochová, M. The Role of Business Angels in the Early-Stage Financing of Startups: A Systematic Literature Review. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygmunt, J. Entrepreneurs’ network characteristics and their perceived success in raising equity: Evidence from the business angel market. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2025, 13, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, A.; Guerini, M.; Ughetto, E. Angel Financing and the Performance of High-Tech Start-Ups. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S. Venture boards: Distinctive monitoring and implications for firm performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drover, W.; Busenitz, L.; Matusik, S.; Townsend, D.; Anglin, A.; Dushnitsky, G. A Review and Road Map of Entrepreneurial Equity Financing Research: Venture Capital, Corporate Venture Capital, Angel Investment, Crowdfunding, and Accelerators. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1820–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, A.; Delecourt, S.; Hasan, S.; Koning, R. When Does Advice Impact Startup Performance? Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P.; Lerner, J. Venture capital distributions: Short- and long-run evidence. J. Financ. 2018, 73, 625–665. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, M.W.; Coombes, S.M.T.; Mazzei, M.J. The Impact of Bootstrapping on New Venture Performance and Survival: A Longitudinal Analysis. Front. Entrep. Res. 2012, 32, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vito, J.; Trottier, K. A Literature Review on Corporate Governance Mechanisms: Past, Present, and Future. Account. Perspect. 2022, 21, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Voegtlin, C. Corporate Governance for Responsible Innovation: Approaches to Corporate Governance and Their Implications for Sustainable Development. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 182–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, C.E.; Dean, T.J.; McDougall, P.P. An Examination of the Impact of Initial Founding Conditions and Decisions upon the Performance of New Bank Start-Ups. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizruchi, M.S.; Stearns, L.B. A Longitudinal Study of the Formation of Interlocking Directorates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannella, A.A., Jr.; Park, J.H.; Lee, H.U. Top Management Team Functional Background Diversity and Firm Performance: Examining the Roles of Team Member Colocation and Environmental Uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 768–784. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-Y.; Hambrick, D.C. Factional Groups: A New Vantage on Demographic Faultlines, Conflict, and Disintegration in Work Teams. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 794–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Rasheed, A.A. Board Heterogeneity, Corporate Diversification and Firm Performance. J. Manag. Res. 2014, 14, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Temprano, M.A.; Tejerina-Gaite, F. Types of Director, Board Diversity and Firm Performance. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 20, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, P.; Terjesen, S.; Davidsson, P. Birds of a Feather Get Lost Together: New Venture Team Composition and Performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 39, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Lai, J.-H. Board Diversity and Post-IPO Performance: The Case of Technology Start-Ups. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 36, 2940–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. Board Size and the Variability of Corporate Performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 87, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Triana, M.C. Demographic Diversity in the Boardroom: Mediators of the Board Diversity–Firm Performance Relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 755–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A., II; Patel, P.P.C. Board of Director Efficacy and Firm Performance Variability. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, D.C.; Clarkson, P.J. Researching and Developing Models, Theories and Approaches for Design and Development. In The Design and Development Process: Perspectives, Approaches and Models; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, T.; Wilner, A. Research impact assessment: Developing and applying a viable model for the social sciences. Res. Eval. 2024, rvae022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; MacMillan, I.C.; Thompson, J.D. Escaping the Prior Knowledge Corridor: What Shapes the Number and Variety of Market Opportunities Identified before Market Entry of Technology Start-Ups? Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S. Opportunity Recognition and Product Innovation in Entrepreneurial Hi-Tech Start-Ups: A New Perspective and Supporting Case Study. Technovation 2005, 25, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bărbulescu, O.; Tecău, A.S.; Munteanu, D.; Constantin, C.P. Innovation of startups, the key to unlocking post-crisis sustainable growth in Romanian entrepreneurial ecosystem. Sustainability 2021, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Kelley, D.J.; Levie, J. Market-Driven Entrepreneurship and Institutions. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Roundy, P.T.; Chok, J.-I.; Ding, F.; Byun, G. ‘Who Knows What?’ in New Venture Teams: Transactive Memory Systems as a Micro-Foundation of Entrepreneurial Orientation. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1320–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial Innovation: The Importance of Context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolopoulos, D.; Söderquist, K.-E.; Mamakou, X.J. Performance Impacts of Innovation Outcomes in Entrepreneurial New Ventures. Entrep. Res. J. 2023, 13, 841–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, W.H.; Huber, G.P.; Miller, C.C.; Doty, D.H.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Studying Changes in Organizational Design and Effectiveness: Retrospective Event Histories and Periodic Assessments. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, D.W.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Enhancing Entrepreneurial Orientation Research: Operationalizing and Measuring a Key Strategic Decision-Making Process. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1055–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agho, A.O. Perspectives of Senior-Level Executives on Effective Followership and Leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2009, 16, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.W.; O’Boyle, E.H.; Miao, C.; Goering, D.; Coombs, J.E. Do Response Rates Matter in Entrepreneurship Research? J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2017, 8, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey Response Rate Levels and Trends in Organizational Research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A.N. Questionnaire Design and Attitude Measurement; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Callegaro, M.; Lozar Manfreda, K.; Vehovar, V. Web Survey Methodology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Truell, A.D.; Bartlett, J.E.; Alexander, M.W. Response Rate, Speed, and Completeness: A Comparison of Internet-Based and Mail Surveys. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2002, 34, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, G.B.; Trailer, J.W.; Hill, R.D. Measuring Performance in Entrepreneurship Research. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciolatti, L.; Rosli, A.; Ruiz-Alba, J.L.; Chang, J. Strategic Alliances and Firm Performance in Startups with a Social Mission. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M.J.; McGee, J.E. Business and Technology Strategies and New Venture Performance: A Study of the Telecommunications Equipment Industry. Manag. Sci. 1994, 40, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeser, H.R.; Willard, G.E. Founding Strategy and Performance: A Comparison of High and Low Growth High-Tech Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, I.; Ebers, M. Dynamics of Social Capital and Their Performance Implications: Lessons from Biotechnology Start-Ups. Adm. Sci. Q. 2006, 51, 262–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashai, N.; Zahra, S.A. Founder Team Prior Work Experience: An Asset or a Liability for Startup Growth? Strateg. Entrep. J. 2022, 16, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Audretsch, D.B. Strategic Entrepreneurship: Exploring Different Perspectives of an Emerging Concept. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Perez, V.; Alonso-Galicia, P.E.; Rodríquez-Ariza, L.; Fuentes-Fuentes, M.M. Professional and Personal Social Networks: A Bridge to Entrepreneurship for Academics? Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.J.; Singer, S.; Herrington, M. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2011 Global Report; Babson College: Babson Park, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. The Fit between Product Market Strategy and Business Model: Implications for Firm Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.; Silverman, B.S. Picking Winners or Building Them? Alliance, Intellectual, and Human Capital as Selection Criteria in Venture Financing and Performance of Biotechnology Startups. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, V.; Kopalle, P.K. Disruptiveness of Innovations: Measurement and an Assessment of Reliability and Validity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Tushman, M.L.; Smith, W.; Anderson, P. A Structural Approach to Assessing Innovation: Construct Development of Innovation Locus, Type, and Characteristics. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An Overview of Psychological Measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.K.K. Mediation Analysis, Categorical Moderation Analysis and Higher-Order Constructs Modeling in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): A B2B Example Using Smart PLS. Mark. Bull. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, M.; Cho, E. An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 25, 6–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, D. Partial Least Squares: Regression and Structural Equation Models; Statistical Associates Publishers: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Foxall, G.R. Construct Validation of a Measure of Adaptive Innovative Cognitive Styles in Consumption. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Harper Collins College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Kupper, L.L.; Muller, K.E. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariate Methods, 2nd ed.; PWS-Kent: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, S.C.; Loch, C.H.; Dong, J. Managing Complexity and Unforeseeable Uncertainty in Startup Companies: An Empirical Study. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanujam, V.; Venkatraman, N. Planning System Characteristics and Planning Effectiveness. Strateg. Manag. J. 1987, 8, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B. Agglomeration and the Location of Innovative Activity. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 1998, 14, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. J. Political Econ. 1991, 99, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Feldman, M.P. R&D Spillovers and the Geography of Innovation and Production. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 630–640. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M.E.; Stern, S. Clusters and Entrepreneurship. J. Econ. Geogr. 2010, 10, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artelaris, P. The Economic Geography of European Union’s Discontent: Lessons from Greece. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2022, 29, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.A.C. Knowledge Sharing and Strategic Capital: The Importance and Identification of Opinion Leaders. Learn. Organ. 2005, 12, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.P.; Francis, J.; Bercovitz, J. Creating a Cluster While Building a Firm: Entrepreneurs and the Formation of Industrial Clusters. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxenian, A. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy. Econ. Dev. Q. 2000, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary-Kelly, S.W.; Flores, B.E. The Integration of Manufacturing and Marketing/Sales Decisions: Impact on Organizational Performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, R.; Shaver, J.M. Export and Domestic Sales: Their Interrelationship and Determinants. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencker, J.C.; Gruber, M.; Shah, S.K. Pre-Entry Knowledge, Learning, and the Survival of New Firms. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z.; Fox, B.C.; Heavey, C. ‘What’s Past Is Prologue’: A Framework, Review, and Future Directions for Organizational Research on Imprinting. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 288–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y.; Zott, C. The Genesis and Metamorphosis of Novelty Imprints: How Business Model Innovation Emerges in Young Ventures. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 554–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Schoonhoven, C.B. Organizational Growth: Linking Founding Team, Strategy, Environment, and Growth among US Semiconductor Ventures, 1978–1988. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 504–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, T.; Zenger, T.R. Entrepreneurs as Theorists: On the Origins of Collective Beliefs and Novel Strategies. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Delmastro, M.; Grilli, L. Entrepreneurs’ Human Capital and the Start-Up Size of New Technology-Based Firms. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2004, 22, 1183–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.C.; Gimeno-Gascon, F.J.; Woo, C.Y. Initial Human and Financial Capital as Predictors of New Venture Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Sirmon, D.G. A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and Its Dimensions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 963–989. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, R.H.; Brigham, K.; Markman, G.D. Entrepreneurial Management as Strategy. In Entrepreneurship as Strategy: Competing on the Entrepreneurial Edge; Meyer, G.D., Heppard, K.A., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Gove, S.; Hitt, M.A. Resource Management in Dyadic Competitive Rivalry: The Effects of Resource Bundling and Deployment. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littunen, H. Networks and Local Environmental Characteristics in the Survival of New Firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2000, 15, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K. Academic Spin-Off’s Transfer Speed—Analyzing the Time from Leaving University to Venture. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.; Dechant, K. Building a Business Case for Diversity. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1997, 11, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, A.S. Structure and Agency in Socialist-Feminist Theory. Gend. Soc. 1991, 5, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Gupta, S. Handling endogenous regressors by joint estimation using copulas. Mark. Sci. 2012, 31, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascle, G. Controlling for endogeneity with instrumental variables in strategic management research. Strateg. Organ. 2008, 6, 285–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Berens, G. The Impact of Four Types of Corporate Social Performance on Reputation and Financial Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D. Detection of influential observation in linear regression. Technometrics 1977, 19, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behn, R.D. Why Measure Performance? Different Purposes Require Different Measures. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, D. The Venture Capital Secret: 3 Out of 4 Start-Ups Fail. The Wall Street Journal, 20 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, I. Intellectual Capital and Business Start-Up Success. J. Intellect. Cap. 2002, 3, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvel, M.R.; Sullivan, D.M.; Wolfe, M.T. Accelerating Sales in Start-Ups: A Domain Planning, Network Reliance, and Resource Complementary Perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1086–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Craighead, C.W. Research at the Intersection of Entrepreneurship, Supply Chain Management, and Strategic Management: Opportunities Highlighted by COVID-19. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Ketchen, D.J.; Shook, C.L.; Ireland, R.D. The Concept of ‘Opportunity’ in Entrepreneurship Research: Past Accomplishments and Future Challenges. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. The Resource-Based View, Resourcefulness, and Resource Management in Startup Firms: A Proposed Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1841–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, J.B.; Keeley, R.H. Predictors of Success in New Technology-Based Ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1990, 5, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, J.B.; Maidique, M.A. Linking Prefunding Factors and High-Technology Venture Success: An Exploratory Study. J. Bus. Ventur. 1986, 1, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.K.; Horwitz, I.B. The Effects of Team Diversity on Team Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review of Team Demography. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 987–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, R.F.J. What’s the Point of Being Different When Everyone Is? The Effects of Distinctiveness on Performance in Homogeneous versus Heterogeneous Categories. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, R.M. On the Use and Misuse of Ratios in Strategic Management Research. Res. Methodol. Strategy Manag. 2009, 5, 75–110. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, T. Why Startups Fail: A New Roadmap for Entrepreneurial Success; Crown Currency: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Multi-Item Constructs and Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | Cronbach a | Composite Reliabilty-CR | Average Variance Extracted-AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human capital factors (measured on discrete, seven-points Likert scales: scale value 7 = very important; scale value 1 = not at all important) | ||||

| Sources: [46,116,128] | ||||

| Please evaluate the importance of the following statements for the performance of the venture: | ||||

| Previous, other-industry, working experience, knowledge and skills of the founding team | 0.8112 | 0.814 | 0.752 | 0.544 |

| Previous, same-industry, working experience, knowledge and skills of the founding team | 0.6874 | |||

| Entrepreneurial experience, such as past start-up experience or prior business ownership, of the founding team a | 0.4874 | |||

| Previous, same-industry working experience, knowledge and skills of employees | 0.6641 | |||

| Previous, other-industry working experience, knowledge and skills of employees a | 0.4965 | |||

| Highly educated and specialized founding team | 0.5215 | |||

| Strategic factors (measured on discrete, seven-points Likert scales: scale value 7 = very important; scale value 1 = not at all important) | ||||

| Sources: [49,50,52,132] | ||||

| Please evaluate the importance of the following statements for the performance of the venture: | ||||

| A coherent pre-launch strategic planning analysis to identify a market arena that others have not recognized or actively sought to exploit a,b | 0.4702 | 0.795 | 0.741 | 0.529 |

| Development of an innovative business model | 0.7791 | |||

| Configuration of the value proposition with close alignment to customer needs and behaviors | 0.7085 | |||

| Focus on the provision of differentiated products/services in the market | 0.7305 | |||

| Innovative marketing positioning strategies a,b | 0.4812 | |||

| Advanced technological capabilities | 0.688 | |||

| The deviation from industry incumbents by fundamentally altering the way we compete a | 0.4516 | |||

| The deviation from industry incumbents in the creation of new products and services b | 0.6885 | |||

| Resource orchestration decisions for value creation | 0.5088 | |||

| Networking (partnership-based linkages) factors (measured on discrete, seven-points Likert scales: scale value 7 = very important; scale value 1 = not at all important) | ||||

| Sources: [48,130,131] | ||||

| Please evaluate the importance of the following statements for the performance of the venture: | ||||

| Networking with research centers | 0.7114 | 0.673 | 0.632 | 0.423 |

| Networking with academia | 0.6482 | |||

| Networking with business incubators/accelerators | 0.5812 | |||

| Networking with other firms in the industry a | 0.4788 | |||

| Finance factors (measured on discrete, seven-points Likert scales: scale value 7 = very important; scale value 1 = not at all important) | ||||

| Sources: [20,68,71,86] | ||||

| Please evaluate the importance of the following statements for the performance of the venture: | ||||

| Bootstrapping | 0.8226 | 0.781 | 0.732 | 0.516 |

| Domestic venture capital | 0.7584 | |||

| International venture capital | 0.6921 | |||

| Seed capital a | 0.4596 | |||

| Business angels a | 0.4178 | |||

| Commercial banks | 0.5513 | |||

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | min | max | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Performance | 167,015 | 141,751 | 34,789 | 875,000 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||||||

| (2) | Members of the founding team | 3.220 | 1.400 | 1 | 6 | 0.2600 | 1.0000 | |||||||||||||||

| (3) | Educational specialization | 0.385 | 0.179 | 0 | 1 | −0.4782 | 0.2778 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||||

| (4) | Board stability | 23.263 | 10.962 | 2 | 48 | 0.3728 | −0.3720 | −0.0707 | 1.0000 | |||||||||||||

| (5) | Meetings | 7.342 | 6.743 | 0 | 12 | −0.1153 | 0.1950 | −0.1904 | −0.0110 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||

| (6) | Female representation | 0.331 | 0.384 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.5069 | 0.0441 | 0.0498 | −0.2598 | 0.0462 | 1.0000 | |||||||||||

| (7) | Human | 4.026 | 1.230 | 3 | 7 | 0.2321 | 0.3428 | 0.1284 | 0.1751 | −0.0747 | −0.2176 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| (8) | Strategic | 5.340 | 0.875 | 2 | 7 | 0.1953 | −0.0907 | 0.1051 | 0.0431 | 0.0847 | 0.1146 | 0.3292 | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| (9) | Networking (Partnership-based linkages) | 4.842 | 1.105 | 1 | 7 | 0.1218 | 0.0149 | 0.0959 | 0.0802 | 0.0921 | −0.2287 | 0.2801 | 0.2978 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| (10) | Financial | 4.738 | 1.329 | 1 | 7 | −0.1156 | 0.0823 | 0.0135 | 0.0482 | −0.0691 | −0.3454 | 0.2485 | 0.2106 | 0.2945 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| (11) | Market growth rate of the industry | 3.254 | 1.247 | 2 | 6 | −0.2588 | −0.0657 | −0.1199 | −0.1255 | −0.2654 | −0.1453 | −0.1203 | −0.0987 | −0.1120 | −0.1725 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| (12) | Rate of technology obsoletion | 2.661 | 1.025 | 2 | 6 | −0.2544 | −0.2556 | −0.1255 | −0.2955 | −0.1286 | −0.2415 | 0.1723 | −0.1289 | −0.3515 | −0.2846 | 0.3768 | 1.0000 | |||||

| (13) | Quality of the local entrepreneurial system | 5.846 | 0.818 | 3 | 7 | 0.1552 | −0.1537 | −0.1407 | 0.0391 | 0.0933 | −0.0206 | 0.0234 | 0.2936 | 0.3210 | 0.0303 | 0.4522 | 0.5221 | 1.0000 | ||||

| (14) | Gross domestic spending in R&D | 3.655 | 1.254 | 1 | 6 | 0.1818 | 0.1540 | 0.2058 | 0.2811 | 0.0921 | 0.2273 | −0.1954 | 0.2547 | 0.3224 | −0.1548 | −0.2598 | −0.3397 | 0.2569 | 1.0000 | |||

| (15) | Size | 8.276 | 4.717 | 2 | 25 | 0.1525 | 0.0774 | −0.0197 | 0.0557 | 0.0151 | 0.0133 | 0.4903 | 0.1784 | 0.2907 | −0.1474 | 0.1213 | −0.0254 | 0.2267 | 0.3540 | 1.0000 | ||

| (16) | Location | 0.703 | 0.400 | 0 | 1 | 0.0239 | 0.0981 | 0.0209 | 0.0988 | 0.0118 | −0.0238 | 0.0632 | 0.2547 | 0.4248 | −0.0602 | 0.4638 | −0.1466 | 0.1579 | 0.6147 | 0.2034 | 1.0000 | |

| (17) | Sector | 0.794 | 0.379 | 0 | 1 | 0.1588 | 0.5231 | 0.2526 | −0.0783 | −0.0227 | −0.0504 | 0.1235 | −0.1835 | 0.0358 | 0.0523 | −0.1213 | −0.2549 | −0.3664 | 0.5543 | −0.0558 | −0.1286 | 1.0000 |

| Regression with Performance Outcome (Volume of Sales a) as the Dependent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Constant | 4.127 *** (0.285) b | 1.635 *** (0.258) |

| Members of founding team | 0.315 ** (0.104) | |

| Educational specialization c | 0.279 (0.182) | |

| Board stability d | 0.088 (0.125) | |

| Meetings e | −0.092 (0.074) | |

| Female representation f | 0.236 ** (0.081) | |

| Human | 1.127 *** (0.354) | |

| Strategic | 0.896 ** (0.427) | |

| Networking (partnership-based linkages) | 1.258 (0.907) | |

| Financial | −1.152 (0.824) | |

| Market growth rate of the industry | −1.893 (0.955) | −1.756 (1.005) |

| Rate of technology obsoletion | −1.024 (0.734) | −1.137 (0.829) |

| Quality of the local entrepreneurial system | 0.647 (0.502) | 0.512 (0.480) |

| Gross domestic spending in R&D | 0.554 (0.839) | 0.627 (0.788) |

| Size | 0.495 (0.109) | 0.352 (0.209) |

| Location g | 0.774 * (386) | 0.652 ** (249) |

| Sector h | 0.641 ** (0.239) | 0.727 ** (0.306) |

| Regression statistics | ||

| n | 108 | 108 |

| F-stat | 3.17 * | 8.79 *** |

| R square | 0.119 | 0.551 |

| Adjusted R square | 0.086 | 0.449 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manolopoulos, D.; Xenakis, M.; Karvela, P. Paving the Way to Success: Linking the Strategic Ecosystem of Entrepreneurial Start-Ups with Market Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188385

Manolopoulos D, Xenakis M, Karvela P. Paving the Way to Success: Linking the Strategic Ecosystem of Entrepreneurial Start-Ups with Market Performance. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188385

Chicago/Turabian StyleManolopoulos, Dimitris, Michail Xenakis, and Panagiota Karvela. 2025. "Paving the Way to Success: Linking the Strategic Ecosystem of Entrepreneurial Start-Ups with Market Performance" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188385

APA StyleManolopoulos, D., Xenakis, M., & Karvela, P. (2025). Paving the Way to Success: Linking the Strategic Ecosystem of Entrepreneurial Start-Ups with Market Performance. Sustainability, 17(18), 8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188385