Abstract

The focus of this research is Gen Z, aiming to fill a research gap by determining the key empowering factors that motivate Gen Z to participate in tourism. The research employed a quantitative approach, utilizing a structured questionnaire-based survey method and descriptive statistics, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The study was conducted on students as an appropriate convenience sample since most students belong to the Gen Z population. By implementing Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) on the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS 2.0), a modified four-factor structure was identified and adapted for measuring empowerment for Gen Z (ZRETS—Gen Z as Residents’ Empowerment through Tourism Scale) as a validated instrument. Identified ZRETS’s (Gen Z as Residents’ Empowerment through Tourism Scale) empowering factors are related to participation within an integral ZRETP model (Gen Z Residents Empowerment through Tourism for Participation). PLS-SEM was employed to examine the structural relationships between empowerment and participation within the ZRETP model (Gen Z Residents Empowerment through Tourism for Participation). The main findings indicated socio-psychological empowerment as a key theoretical base for understanding Gen Z’s participation in tourism. For environmental empowerment and economic empowerment, their mediating role was confirmed, where environmental empowerment is a key mediator and economic empowerment is a result of socio-psychological empowerment effects. Political empowerment was found irrelevant and was excluded from the model, indicating the need for creating a new approach for engaging Gen Z in participation and alternative participation channels more oriented on digital media. The main paper contribution represents the validated ZRETP model (Gen Z Residents Empowerment through Tourism for Participation), as an integrated empowerment–participation framework tailored for Gen Z. Theoretically confirmed importance of Gen Z’s internal empowerment (evident from socio-psychological empowerment effects) and environmental values (evident from environmental empowerment effects) in creating benefits (evident from economic empowerment effects) can guide practitioners in creating sustainable tourism strategies, emphasizing socio-psychological and environmental empowerment, which motivate Gen Z to participate and lead to economic prosperity. Limitations in this paper are related to the convenience sample of students and the PLS-SEM that is used in validating the ZRETP model (Gen Z as Residents’ Empowerment through Tourism Scale).

1. Introduction

Tourism development has been predominantly influenced by the interests of investors, politicians, public authorities, and the private sector for many years. As the focus on sustainable tourism development grows, residents are assuming a new role as active participants in shaping the development of their destinations. The Global Development Research Center emphasizes that a crucial aspect of sustainable tourism planning and development is the involvement of the local community in the decision-making process; see [1]. Similar conclusions are drawn by numerous other studies, which suggest that sustainable development becomes externally imposed without considering stakeholder interests. Therefore, it is not truly sustainable; see the references [2,3,4,5]. Tourism that is planned without residents’ input often fails to meet the long-term needs of local communities that should be positively affected by it. Involving residents in tourism decision-making will empower communities and ensure sustainable tourism development, truly reflecting their needs and priorities. It, in turn, supports the quality of life they wish to achieve. It is also emphasized by Li [6], who argued that only by including local communities in the decision-making process can we ensure that their values, traditions, benefits, and way of life are respected.

Although today’s youth will be the key drivers of sustainable tourism development in the future, their voices are rarely heard or included, highlighting the need for a more inclusive approach. Generation Z remains an understudied group, which will soon become the primary force behind sustainable tourism development. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate and understand the mechanisms that can facilitate and enhance Gen Z engagement in sustainable tourism development initiatives.

Gen Z participation can be realized only if they feel empowered. Strengthening the participation of residents requires understanding what psychologically, socially, environmentally, economically, and politically empowers this generation to boost and secure their involvement in sustainable tourism; see ref. [7]. Gutierrez [8] also proposed a participation-empowering framework in her research, suggesting its application to specific CBT projects in particular destinations, as well as participation and empowerment research on disadvantaged groups, such as women, youth, informal workers, and others.

A key stakeholder involved in sustainable tourism development is today’s youth. The younger generation should be more involved and included in the planned strategies and approaches. Generation Z, which will become the driving force behind future development, remains an understudied group. Previous empowerment scales, such as REST 2.0. [9], were validated mainly among millennials, while the Community-Based Tourism (CBT) framework [8,10] broadly conceptualizes empowerment but does not address generational differences. Although recent studies confirm that Generation Z exhibits strong pro-sustainable behaviors [11,12,13,14], the primary focus is on behavior, and only afterward are the empowerment mechanisms mentioned. This gap opens up the possibility and need to research and explore the empowering factors that specifically motivate Generation Z residents to engage in practices and decisions that will lead to more sustainable tourism development. The present study introduces and validates the ZRETP model, which builds on the empowerment and participation framework but is tailored to Generation Z.

Thus, this study aims to address the identified gap by answering the following questions:

- Which empowerment factors directly impact Gen Z’s participation in sustainable tourism development?

- How do empowerment factors indirectly influence Gen Z’s participation in sustainable tourism development?

- Are there mutual influences between the empowerment factors for the Gen Z residents?

The paper is organized into five main parts. Following the introduction, the second part presents a literature review, hypothesis development, and the research conceptual framework that explains the ZRETP model. In the paper’s third part, the methodology is described. Within the research results, the fourth part describes sample characteristics, EFA, and the ZRETP measurement and structural model assessments, including hypothesis testing and discussion. The fifth and final part consists of concluding remarks reflecting on theoretical and practical contributions, outlining methodological limitations, and proposing future research directions.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Importance of Residents’ Participation in Sustainable Tourism Development

The role of local communities in decision-making is essential for establishing the long-term sustainability of tourist destinations. Understanding the process serves as a key tool for managing tourism development sustainably; see [15].

When communities are involved in decision-making, several positive outcomes typically occur. Ideas become more innovative, decisions are more representative, the overall quality of those decisions improves, conflicts are reduced, and trust is built; see [3]. Participation helps align tourism development with local values and enhances the quality of life for residents [16,17]. Research by Lee [18] confirmed that local involvement has a direct, positive, and significant influence on how people perceive the benefits of sustainable tourism. Meanwhile, Cheng et al. [19] demonstrated that local community engagement encourages more environmentally responsible behavior and attitudes toward sustainable tourism development.

Still, it is essential to note that many authors, through their research, highlight shortcomings and the limited involvement of local communities in decision-making processes. Cole [20] and Birkić et al. [21] highlight persistent institutional barriers that hinder participation, suggesting that the limited role of local communities in tourism development is more a result of the way participation is structured than a lack of interest on the part of the communities themselves. Mak et al. [17] observed that community participation is often reduced to consultations that fail to provide meaningful influence, which Arnstein [22] called “tokenism”, a situation where communities may have a voice but lack actual decision-making power. Research conducted by Tong, Li, and Yang [23] supports this claim. The authors found that the tourism system plays a strong role in shaping community participation, with empowerment serving as a mediating factor. They emphasize that institutional reforms are crucial to achieving genuine participation.

Without genuine and meaningful inclusion, support for sustainable tourism development can quickly disappear. The research by Bašan et al. [16] addressed measurable benefits, emphasizing that community participation plays a crucial role in supporting sustainable tourism practices. The authors found that perceived positive personal economic benefits among younger residents led to a greater perception of their contribution to sustainable tourism.

Furthermore, willingness to participate enhances the empowerment of local stakeholders, with the perception of environmental impacts playing a key role in engaging residents, as noted in the study by Shafieisabet and Haratifard [24].

Lee [18] emphasized that long-term support for sustainable tourism development is challenging to maintain, even with its benefits, unless genuine community involvement is ensured. This concern is present in the research of Moreira dos Santos et al. [9] and Timothy [25], who argue that local populations are often excluded from decision-making processes and lose the opportunity to express their views when control over governance and political decisions remains in the hands of external investors and institutions.

And yet, young people, as a key group in the community, are often overlooked as stakeholders within their local community. While many researchers have emphasized the importance of involving residents in decision-making, only a few recognize the importance of the younger generation in this process. Numerous authors clearly emphasize that early participation in the process is a fundamental principle of sustainable development [26,27,28]. Gautam & Bhalla [7] noted that a population empowered and actively participating in activities focused on achieving sustainable tourism growth is more likely to remain engaged in the long run. Similarly, Dibra and Oelfke [29] (p. 1) highlight the importance of educating young people and encouraging their active involvement, noting that “it is internationally accepted that education is a vital tool, since achieving sustainable development is essentially a process of learning.”

Research indicates that “young” voices are often excluded in this context. Yang et al. [30] (p. 14) emphasize that there are “few host children studies and fewer of these reflect children’s voices,” while Seraphin & Green [31] (p. 11) concluded that “the tourism industry is only perceived, developed and understood from the adults’ prism.”

As the future primary force for sustainable tourism development, Generation Z remains vastly underrepresented in research and practice. Generation Z has shown a strong interest in sustainability and social participation. They are digital natives, socially conscious, and innovative, yet they have been overlooked in the formal decision-making process [32,33]. Rather than relying on traditional institutions, they use digital platforms to express their opinions through social media and participate in various movements.

Lu et al. [14] demonstrate that Generation Z’s environmentally responsible behavior is strongly influenced by digital engagement and creative tourism experiences, confirming this generation’s potential as a key driver in shaping sustainable tourism.

These diverse forms of participation will pose a challenge for planners, requiring them to redefine the methods and ways to motivate and engage young generations [34].

In addition to direct involvement, participation can take various forms, including volunteering, advocacy, entrepreneurship, and co-creating tourism experiences. As community participation emerges as a foundation for sustainable development, it is crucial to examine the mechanisms that can facilitate and enhance this participation. Participation cannot be fully realized if people do not feel empowered. Empowerment strengthens residents to make a difference, gives them the skills to take action, and fosters respect for their contributions. Strengthening the participation of residents, especially Generation Z, requires understanding what psychologically, socially, environmentally, economically, and politically empowers this generation to boost and secure their participation in sustainable tourism [7].

Scheyvens and van der Watt [35] expand this framework by adding two further dimensions—cultural and ecological—and emphasize that sustainable tourism can only be achieved through multidimensional empowerment.

2.2. Empowering Residents to Participate in Tourism Decision-Making

Empowerment is a widely discussed concept that goes hand in hand with stakeholder participation, particularly when the main goal is the development of tourism with sustainability in mind. Residents, including young people, are becoming increasingly active participants in planning, decision-making, and implementing tourism initiatives [36,37,38]. Empowerment can be defined as the activation of the confidence and capabilities of previously disadvantaged or disenfranchised individuals or groups, enabling them to exert greater control over their lives, challenge unequal power relations, mobilize resources to meet their needs, and work towards achieving social justice [35]. In tourism, empowerment has been conceptualized as residents’ enhanced control, skills, and opportunities to participate in and benefit from tourism development. Various dimensions, such as the development of confidence, the feeling of control, motivation, and access to adequate resources, among others, influence the extent to which residents believe they can and do influence tourism development and its outcomes in their destinations [39,40,41].

This research adopts a multidimensional view of empowerment, examining it through five key dimensions: psychological, social, environmental, economic, and political [25].

Zhou, Wang, and Zhang [42] employed a similar framework encompassing political, social, psychological, and economic aspects in their study. They confirmed the importance of the link between these aspects for sustainable development.

Each dimension offers distinctive motivational and enabling mechanisms, while their interaction is expected to provide the foundation for a comprehensive empowerment–participation framework tailored to a specific generation. In their recent validation of the Resident Empowerment through Tourism scale, Castillo-Vizuete et al. [43] confirm that these dimensions significantly predict residents’ intention to engage in ecotourism.

Recent studies show that local residents do not value all dimensions of empowerment equally but place greater emphasis on economic and political empowerment [44]. While earlier research primarily focuses on empowerment among adults, recent studies highlight the growing role of young residents, particularly those in Generation Z, whose attitudes and behaviors will play a crucial role in shaping future tourism development [45,46,47]. Therefore, this research will examine key dimensions and their influence on Generation Z’s motivation to participate in and contribute to sustainable tourism development.

Psychological empowerment refers to the belief in one’s ability to influence outcomes and make a meaningful difference. It is about how people see themselves regarding capability, self-confidence, and purposefulness. For Generation Z, who often express strong environmental and social values, psychological empowerment and the confidence that they can shape the future of their communities can be utilized as a tool for positive change in tourism development, playing a crucial role in their willingness to participate in sustainable tourism initiatives [7,13]. This aligns with findings in the field of educational psychology, where student empowerment has been linked to long-term commitment to sustainability-related careers and behaviors [48,49].

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the study by Megawati et al. [50] demonstrates that psychological empowerment has the strongest impact on supporting tourism, and they also conclude that the use of technology reinforces this effect.

Social empowerment is shaped by an individual’s relationship with their community and the extent to which they feel a sense of belonging. Generation Z often participates in collective initiatives through peer networks and social media platforms, prioritizing collaboration and engagement.

A strong sense of social inclusion and mutual trust increases the likelihood that young people will advocate for sustainable tourism practices within their communities [51,52,53,54]. In other words, when young people feel that they are part of the community and that this community values their ideas and diverse input, they are more likely to participate and come together around a common goal [34].

Although psychological and social empowerment provide motivation and readiness, environmental empowerment offers practical direction for that motivation. This form of empowerment involves the belief that one has the responsibility and the capacity to protect the natural environment. Generation Z is a generation defined by environmental crises; therefore, they are highly environmentally aware [31]. Their concerns about climate change, biodiversity loss, and sustainability were well-documented [11,12,19]. If young people believe they can make a tangible environmental difference through tourism, whether by engaging in conservation, supporting green infrastructure, or promoting environmental education, they are more likely to participate actively [14].

Economic empowerment refers to the perception that tourism can offer a fair chance to earn, innovate, and grow; in other words, fair and meaningful economic opportunities for all. For Generation Z, this includes employment, entrepreneurship, and personal development opportunities. Economic empowerment may be particularly relevant among youth due to increasing concerns about job security, economic inclusion, and self-sufficiency. When the younger generation perceives tourism as offering future job opportunities, entrepreneurial possibilities, career development, community contributions, or the potential to build more ethical businesses, they are more likely to be motivated to engage and put in more personal effort [7,16,53].

Ultimately, political empowerment entails the conviction that one has a voice and influence in the decision-making process. Generation Z is often skeptical of traditional political institutions; nonetheless, they actively shape public conversation, primarily using online platforms and participating in various campaigns. In tourism, this means that their participation declines unless they are genuinely listened to and given a chance to co-create. Political empowerment gives them the sense that they are recognized as contributors with the ability to shape the future [34,55,56,57].

What makes empowerment particularly relevant in this context is the value of each individual dimension and how they interact with and reinforce one another.

2.3. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

The research conceptual framework is defined in the context of Community-Based Tourism (CBT), which “aims to create a more sustainable tourism industry, focusing on the host community in terms of planning and maintaining tourism development” [51] (p. 50). CBT is viewed as an empowerment approach that recognizes the community as a vital actor in sustainable development, where community participation in tourism development is a key element [58]. CBT is gaining increasing acceptance as a tourism development approach, offering more opportunities for community empowerment [56]. Following this, Gutierrez’s [8] model suggests that by meeting the requirements of existing communities for empowerment to participate effectively in CBT, the level of participation and empowerment can be increased through continuous interaction. Similarly, Elshaer et al. [59] and Aleshinloye et al. [60] argued that there is a close link between empowerment and participation. Meanwhile, Khalid et al. [45] emphasized empowerment as an important predictor of a community’s support for sustainable tourism development. Thus, empowered individuals are more likely to take part in tourism initiatives.

This research aims to determine the empowering factors that can motivate Gen Z to participate actively in sustainable tourism development. For this purpose, the ZRETP (Gen Z Residents Empowerment through Tourism for Participation) model was developed for Gen Z residents. This research thereby closes the identified research gap in two ways: by investigating Gen Z as an underexplored segment of residents and by placing an innovative empowerment–participation framework adapted to Gen Z.

Empowerment, a multidimensional construct tailored to Gen Z (ZRETS—Gen Z as Residents’ Empowerment through Tourism Scale), is defined using the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS 2.0) model [9]. It encompasses the psychological, social, environmental, economic, and political dimensions of empowerment.

Psychological empowerment has been recognized as one of the key dimensions of individual and collective participation [40,41]. In tourism, the psychological dimension significantly predicts support for sustainable initiatives [9] and residents’ support for tourism [61]. It is also determined to be a significant predictor of perceived sustainable tourism contribution for the older residents [16]. It provides evidence for the presumption that psychological empowerment contributes to participation in sustainable tourism:

H1.

Gen Z’s psychological empowerment positively influences their participation in sustainable tourism development.

Dolezal and Novelli [56] emphasize the role of partnerships and collaboration in empowering communities. Empowered local stakeholders can contribute to reinforcing social relationships and prioritizing community interests through participation in sustainable tourism development [24]. In tourism, socially empowered residents are likely to perceive fewer negative impacts of tourism and more substantial benefits [62]. Aleshinloye et al. [60] find social empowerment a significant predictor of residents’ involvement in tourism. It is reasonable to assume that social empowerment contributes to increased participation.

H2.

Gen Z’s social empowerment positively influences their participation in sustainable tourism development.

Shafieisabet and Haratifard [24] pointed out that “the perceived environmental impacts of local tourism stakeholders have a significant effect on participation in sustainable tourism development.” Additionally, residents’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism have a positive impact on community participation and environmentally responsible behavior [19]. Environmental empowerment significantly contributes to attitudes toward ecotourism [43]. Therefore, it is assumed that there is a positive relationship between environmental empowerment and involvement in sustainable tourism.

H3.

Gen Z’s environmental empowerment positively influences their participation in sustainable tourism development.

Participation contributes to sustainable economic development [63]. Personal economic benefits from tourism are identified as a significant predictor of the perceived contribution of sustainable tourism for a younger group of residents [16]. Economic empowerment positively affects residents’ support for tourism [61] and is a significant predictor of attitudes about ecotourism [43]. It follows the assumption that economic empowerment contributes to inclusion in sustainable tourism.

H4.

Gen Z’s economic empowerment positively influences their participation in sustainable tourism development.

Ranasinghe and Pradeepamali [64] found that political empowerment has positive impacts, leading to residents’ support for tourism development. For political empowerment, Neuts, Kimps, and van der Borg [62] point out its direct effects on the positive impacts of tourism. Political and social empowerment are identified as essential predictors of residents’ inclusion in tourism [60]. Thus, it is assumed that there is a positive relationship between political empowerment and participation.

H5.

Gen Z’s political empowerment positively influences their participation in sustainable tourism development.

Gautam and Bhalla [7] identify psychological and social factors as crucial for sustainable tourism development. Psychological and social empowerment may provide the necessary motivational and emotional readiness, but without clear channels for environmental and economic engagement, motivation often fails to translate into action. Studies have shown that environmental awareness and economic opportunity can translate identity and motivation into concrete actions and behaviors [16,19]. Following this, our model assumes that environmental and economic empowerment play a mediating role in the relationships of psychological and social empowerment with participation. The following hypotheses for their mediating role are defined:

H6.

Environmental empowerment mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and Gen Z participation in sustainable tourism development.

H7.

Economic empowerment mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and Gen Z participation in sustainable tourism development.

H8.

Environmental empowerment mediates the relationship between social empowerment and Gen Z participation in sustainable tourism development.

H9.

Economic empowerment mediates the relationship between social empowerment and Gen Z participation in sustainable tourism development.

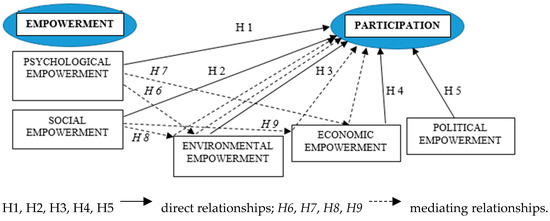

The conceptual ZRETP model illustrates the direct relationships between each empowering factor and participation in sustainable tourism development. Environmental and economic empowerment are considered mediators in the relationships of psychological and social empowerment with participation, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual ZRETP model.

3. Data and Methodology

According to the proposed hypotheses, a quantitative approach was taken to fulfill the research goal. In empirical research, a structured questionnaire was employed as the survey method. The empowerment scale was taken from previous research by Moreira dos Santos et al. [9], as presented in Appendix A, Table A1. The items are adapted, and all are generally formulated for tourist destinations, allowing students on whom the research was conducted to evaluate each item in the context of their own tourist destination.

A question on empowerment comprising 24 items, based on the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS 2.0). The RETS 2.0 includes five empowering factors for residents:

- Psychological empowerment—5 items (“Makes me proud to be a resident in my place”, ”Makes me feel special because people travel to see my country’s unique features”, “Makes me want to tell others about what we have to offer in my place”, “Reminds me that I have a unique culture to share with visitors”, and “Makes me want to work to keep my place special”);

- Social empowerment—3 items (“Makes me feel more connected to my place”, “Fosters the sense of community spirit within me”, and “Provides ways for me to get involved in my place”);

- Environmental empowerment—6 items (“Reminds me that I have the obligation to protect my natural surrounding”, “Makes me want to adopt reuse, reduce, and recycle practices”, “Provides ways for me to promote environmentally friendly initiatives”, “Makes me want to protect biodiversity in my place”, “Reminds me that I have the obligation to preserve our natural heritage”, and “Makes me feel I can contribute to my community’s wellbeing through preservation of physical surrounding”);

- Economic empowerment—6 items (“Provides ways for me to use funds allocated from tourism to improve my place”, “Makes me want to control my available income,” “Makes me feel I can benefit economically long-term”, “Provides ways for me to support my family”, “Makes me feel I can improve my standard of living”, and “Makes me feel I can benefit from tourism even if I am not employed in tourism”);

- Political empowerment—4 items (“I have a voice in tourism development decisions in my place”, “I have access to decision-making process when it comes to tourism in my place”, “My vote makes a difference in how tourism is developed in my place “, and “I have an outlet to share my concerns about tourism development in my place”).

The participation in sustainable tourism development was taken from Thang and Thanh [65], as presented in Appendix A, Table A2, and measured with 4 items (“I am willing to participate in the development of sustainable tourism in my place”, “I am willing to adopt sustainable tourism practice in my business and private life”, “I am committed to promoting the benefits of sustainable tourism to others”, and “I am willing to invest time and resources in the development of sustainable tourism in my place”). Participation items are adapted to sustainable tourism.

In total, the questionnaire comprised 31 items, translated into Croatian and integrated into the research instrument for the purpose of conducting the study. The questionnaire included socio-demographic questions (related to gender, study year, and program), followed by questions on empowerment and participation. Items are measured using a five-point Likert scale. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each of the proposed statements and evaluate it on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree,” 2 indicated “mostly disagree,” 3 indicated “neither agree nor disagree,” 4 indicated “mostly agree,” and 5 indicated “strongly agree.”

The research was conducted with prior approval and a positive opinion from the Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management in Opatija, Croatia. Consent to conduct the research was also obtained from each course holder whose students participated in the study, as well as from students who were initially informed about the research and subsequently gave their consent to participate. Students accessed the questionnaire in the hall via a QR code. The study was conducted from 3–7 February 2025, on a convenience sample of undergraduate students from the first to fourth year at the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management in Opatija, Croatia. A total of 313 questionnaires were collected, which were correctly completed and included in the analysis. The sample size can be considered adequate, as the number of observations per variable exceeds the recommended minimum of at least five observations per variable [66] (p. 100).

Data analysis was conducted by applying various statistical methods. The IBM SPSS 29 statistical software was used for descriptive statistics (frequency, relative share, mean, and standard deviation). Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), with Principal Component Analysis (PCA), was implemented on the RETS 2.0 scale [9], which represented a validated instrument for measuring the empowerment of local residents in the context of tourism, with the purpose of examining the factor structure and adequacy of implementing RETS 2.0 empowerment’s dimensions on Gen Z residents (ZRETS—Gen Z as Residents’ Empowerment through Tourism Scale). Identified empowerment factors in ZRETS are used as a latent variable in the ZRETP model and related to participation. SmartPLS 4.1.1.2 software was used to apply Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to investigate the structural relationships between the latent variables of empowerment and participation and their corresponding manifest variables in the proposed ZRETP model. PLS-SEM was considered suitable for the ZRETP model validation because of little prior knowledge on how integrated empowerment variables are related to Gen Z participation, suitability for testing a complex model since ZRETP has several latent variables and mediating effects, sets of criteria for ZRETP model assessment, and predictive evaluation of Gen Z participation in sustainable tourism [67].

4. Research Results and Discussion

4.1. Sample Characteristics

A total of 331 students participated in the research. Students can be considered an appropriate convenience sample, since most students belong to the Gen Z population, are accessible respondents for academic research, and are sensitive to ecology, sustainability, and similar topics. Most respondents were female (75.7%). Students from all years of undergraduate study participated in equal shares: first year, 28.8%; second year, 24.6%; third year, 24.9%; and fourth year, 21.7%. The majority of respondents are undergraduate university students of Business Economics in Tourism and Hospitality (75.7%), while the remaining share are students of Management of Sustainable Development.

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Latent Dimension Identification

The RETS 2.0 scale was originally developed and validated by Moreira dos Santos et al. [9]. For that purpose, they conducted research on a sample primarily composed of millennials, with a smaller proportion of Generation Z (approximately 9%). Gen Z represents a different resident group compared to millennials, with different values and modes of participation. While the RETS 2.0 scale has been validated, applying it to Gen Z, it is justified to test whether the same empowerment dimension emerges or the factor structure is modified. EFA provides a means to identify whether certain indicators or dimensions are less relevant and if they should be excluded, ensuring an empirically grounded scale serving as a basis for further validation through PLS-SEM. As a result of EFA implementation, the scale called ZRETS (Gen Z as Residents’ Empowerment through Tourism Scale) is an empowerment measurement scale, tailored to the specific characteristics of Gen Z. The analysis results of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

EFA results for Gen Z Residents Empowerment through Tourism Scale (ZRETS).

The suitability for conducting EFA was determined using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin coefficient (0.952; KMO > 0.6), indicating there are enough factors to meet the needed percentage of variance explained, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 5721.937; p = 0.000, p ˂ 0.05) points to the existence of sufficient correlation among the variables [68] (p. 144), [33] (p. 103). Thus, an excellent suitability for factor analysis is established. Based on identified suitability, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation was performed. The results show four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, which explained 70.927% of the total variance, with factor loadings ranging from 0.531 to 0.852. Thus, the results indicated that the factors were acceptable, as they provided eigenvalues greater than 1, explained a total variance of more than 60%, and had factor loadings above 0.5 [66] (pp. 107, 115).

EFA results indicated a four-factor structure of the ZRETS for the Gen Z empowerment measurement: socio-psychological, environmental, economic, and political empowerment, compared to the five-factor structure defined by RETS 2.0 for residents’ empowerment. The results show a modified factor structure for Gen Z empowerment; social and psychological empowerment factors were integrated as socio-psychological empowerment (Factor 1), which explains 50.525% of the total variance. From the EFA results (Table A3), it is evident that psychological and social dimensions loaded strongly on a common factor, indicating that Gen Z does not clearly distinguish psychological from social empowerment and perceives them as a single construct. This aligns with Gen Z generational characteristics, who have a strong attachment to collective identities and personal feelings linked to belonging to different groups and their social context. “One of the challenges of this generation is forming an independent identity and self-regulation in a digital, global, across-the-border era that offers a variety of possibilities and communities.” [69] By combining psychological and social empowerment into a single factor, model parsimony is ensured, since the model was simplified and with fewer factors, ZRETS retains its explanatory power [67].

In total, the four-factor structure explained 70.927% of the total variance of the ZRETS and exceeded the recommended threshold of 60% [66] (p. 107), confirming the robustness of the factor structure. A total variance is mostly explained by socio-psychological empowerment (Factor1—50.525%), followed by environmental empowerment (Factor2—10.003%). Economic empowerment (Factor 3—5.722%) and political empowerment (Factor 4—4.677%) contribute a smaller share to the variance explanation.

4.3. Analysis of Initial ZRETP Model Results

The identified empowering factors of the ZRETS are used as the latent variables in the ZRETP model and related to participation, as presented previously in Figure 1. PLS-SEM was employed to identify the existing structural relationships between the latent variables of empowerment and participation and the manifest variables of the proposed model. Initial results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Path coefficients analysis of the initial ZRETP model.

Path coefficients (β-values) indicated an insignificant and a weak negative effect of political empowerment on participation (β = −0.123, p = 0.409) and had no significant relationship with other empowerment factors. The exception is socio-psychological empowerment, which has a significant and extremely high impact on political empowerment (β = 0.950; p = 0.000), indicating the overlap of political with socio-psychological empowerment and the fact that political empowerment is not distinct from psychological empowerment and does not behave as a separate construct. Additionally, there are indirect relationships between other empowerment factors and participation, where political empowerment plays a mediating role, which are also all insignificant (all p > 0.4) and mostly negative. Cross-loading issues are identified for political empowerment, while the socio-psychological empowerment variable loads strongly on political latent constructs, even at higher values than on its latent construct. It is an additional indication that the constructs are not distinct from each other, leading to a lack of ZRETP model discriminant validity, including political empowerment as a latent variable.

Power analysis was conducted at significance levels of 1% and 5%, with test power at 80% and 90%, where the required sample sizes are calculated to achieve the calculated path coefficient among constructs in the ZRETP model. Required sample sizes for socio-psychological, environmental, and economic empowerment range from 45 to 128 respondents, at 5% significance and at 80% power. To detect such a low effect of political empowerment on participation, an unrealistically large sample of at least 465 respondents or higher is required, indicating that these effects are practically irrelevant.

Following the determined findings of its insignificant effects on participation and mediating effects, lack of clear diction from other constructs in the model, and unrealistically large sample size required, the authors decided to exclude political empowerment from the model and proceed with further analysis.

Excluding this variable from the ZRETP model contributed to its improved internal consistency, evident in the increase in the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient’s value from 0.843 to 0.874. On the other hand, its exclusion from the model did not affect the values of the environmental and economic empowerment coefficients of determination. It had a minimal impact on the change in participation amount of variance explained, which decreased from 0.425 to 0.418. Additionally, the path coefficients’ values and significance remained unchanged after excluding political empowerment. Following those mentioned above, the exclusion of political empowerment from the model is considered justified, contributing to the clarity and parsimony of the ZRETP model.

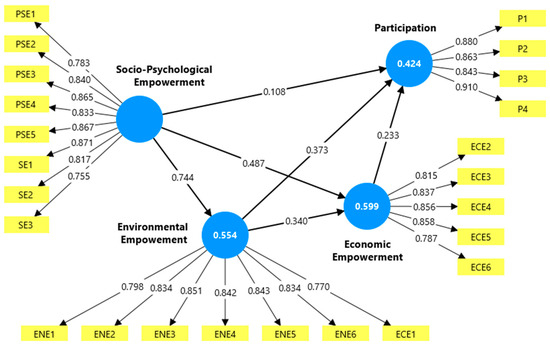

After excluding political empowerment from the model, a new calculation using Partial Least Squares—Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was conducted for the ZRETP model. The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

ZRETP model results.

In advance, the ZRETP model assessment is presented through two steps: (1) the measurement model assessment: internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha and CR; convergent validity, outer loadings and AVE; discriminant validity, cross-loading; Fornell–Lacker Criterion; heterotrait–monotrait ratio, HTMT; and (2) structural model assessment, VIF, R2, f2, and Q2.

4.4. Measurement Model Assessment

The measurement model illustrates how measured variables correspond to the constructs [68] (p. 764). For the ZRETP model evaluation, initial measures are used to determine the internal consistency of the model in the context of the scales used to measure Gen Z empowerment and participation in sustainable tourism development.

4.4.1. Internal Consistency and Reliability

Table 3 presents the results of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), which measure the internal consistency and reliability of the ZRETP model.

Table 3.

Internal consistency—ZRETP model.

Calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients range from 0.874 to 0.935. Composite reliability (CR) values range from 0.918 to 0.946, indicating that the items are closely related to their respective constructs. Generally acceptable values for both indicators are above 0.7, as recommended by Hair et al. [66] (p. 161) and [67] (p. 760) and. Thus, the values of both internal consistency measures confirm very high consistency and reliability of items within the Gen Z latent variables of empowerment (socio-psychological, environmental, and economic) and participation in sustainable tourism development.

4.4.2. Convergent Validity

Table 4 presents the results of evaluating the ZRETP model’s convergent validity using outer loadings and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

Table 4.

Convergent validity—AVE and outer loadings.

Thus, for the ZRETP model, internal consistency and convergent validity is confirmed, while the following conditions are fulfilled: (1) standardized loadings are above 0.5; (2) Cronbach’s alpha is above 0.7 and below 0.95; (3) CR values are greater than 0.7; (4) outer loadings are above 0.708; (5) AVE values are greater than 0.5. Thus, it is determined that in the ZRETP model, constructs are well-represented by their indicators [70]. Therefore, the internal consistency and convergent validity were established.

4.4.3. Discriminant Validity

The condition for evaluating model discriminant validity is previously determined convergent validity [71], which is fulfilled. Thus, in advance, discriminant validity of the ZRETP model is evaluated using cross-loading, the Fornell–Lacker Criterion, and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) to examine whether the construct can be distinguished from others [70]. Calculated cross-loading values are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity—cross-loading criterion.

Cross-loading as a measure indicating correlation among constructs in the model. According to this criterion, an indicator’s outer loading on the associated construct should be greater than any of its cross-loadings or correlations on other constructs [67] (p. 122). From Table 5 and the detailed cross-loading values (Table A4), it is evident that loadings exceed the cross-loading in the ZRETP model, indicating that this discriminant validity criterion is fulfilled.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion, as a measure of discriminant validity, compares the shared variance within the constructs to the shared variance between the constructs, where the shared variance within should be larger than the shared variance between [68] (p. 761). Calculated values for the ZRETP model are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Discriminant validity—Fornell–Lacker criterion.

For the ZRETP model, it is evident that the diagonal values, which represent the square roots of the AVE for each construct, are all higher than the correlations of the construct with other latent variables, indicating that all constructs are valid measures of unique concepts [67] (p. 131). Additionally, discriminant validity should be evaluated using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT), for which the values are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT)—confidence intervals bias corrected.

For the HTMT, threshold values for conceptually distinct constructs should be lower than 0.9 and, based on confidence intervals, significantly different from 1 [68] (p. 776). The HTMT values in the ZRETP model for all variables ranged from 0.606 to 0.809, meeting the criterion of a value below 0.9. Additionally, within the confidence interval, correlation values do not include the value 1, and all values are below this threshold.

Following the cross-loading criterion, the Fornell–Lacker Criterion, and the HTMT assessment of discriminant validity, discriminant validity is established for the ZRETP model, confirming that each construct is conceptually and sufficiently distinct from the others.

4.5. Structural Model Assessment

The structural model illustrates the interrelationship between the constructs [68] (p. 764). The structural model evaluation includes analyses of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2), with the calculated values for the ZRETP model presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

VIF, effect size, determination coefficient, and predictive relevance—ZRETP.

The first step in evaluating the structural model is usually to check the values of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and assess the level of collinearity. As a rule of thumb, VIF values of 5 or above indicate critical collinearity issues among the indicators of formative measures constructs [67] (p. 147). Calculated VIF values for latent variables in the ZRETP model ranged from 1.871 to 3.442, indicating no critical collinearity among the indicators or between the constructs, while all values are below 5.

The coefficient of determination (R2) indicates the amount of variance explained by the endogenous latent variables in the structural model [68] (p. 763), and the R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 can be considered substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively [68] (p. 780). The R2 value of 41.8% indicates that the endogenous variable, participation (P), is explained by exogenous variables of empowerment (socio-psychological, environmental, and economic), which is interpreted as a weak relationship. For the economic empowerment (ECE), 59.9% of the variance is explained by the exogenous variables, socio-psychological (SPSE) and environmental empowerment (ENE), indicating a moderate relationship. Exogenous construct socio-psychological empowerment (SPSE) explains 55.4% of the endogenous latent variable environmental empowerment (ENE) and can be considered moderate.

The effect size (f2) measure is used to assess the relative impact of a predictor construct on an endogenous construct [68] (p. 761), and following Cohen, effect sizes of less than 0.02 indicate no effect, and values of 0.02 represent small, 0.15 medium, and 0.35 large effects of an exogenous construct [68] (p. 780). Calculated f2 values for the ZRETP model indicate that the removal of the exogenous variable, socio-psychological empowerment, does not influence the participation’s R2 value (f2 = 0.007). Still, it has a medium effect on economic empowerment (f2 = 0.263) and a large impact on environmental empowerment (f2 = 1.242). Other exogenous variables have a negligible effect on the R2 values.

Q2 is a measure of a model’s predictive power. The Q2 values larger than zero for a particular endogenous construct indicate that the path model’s predictive accuracy is acceptable for that construct [68] (p. 780). The cross-validated predictive ability test (CVPAT) was conducted to test the predictive relevance of the ZRETP model. Q2 values for all three exogenous variables are above zero. Additionally, a mostly moderate relationship was determined, as indicated by the R2 values of the endogenous constructs, implying that the exogenous variable can predict the endogenous variable well, and the predictive relevance of the ZRETP model is acceptable.

4.6. Hypothesis Testing

This research examines the relationships between Gen Z empowerment factors and their participation in sustainable tourism development through a structural equation model. To test the hypothesis, the path coefficients are assessed in terms of their significance and relevance using bootstrapping and its 95% confidence intervals [67] (p. 223–224), with a sample of 5000 subsamples. The results of the path analysis are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Results of path analysis for hypothesis testing.

To ensure a clear context for hypothesis testing, given the complexity of defining latent variables in the ZRETP model, it is necessary to provide a detailed explanation of the procedure. The RETS 2.0 scale was utilized as an initial framework for residents’ empowerment, which encompasses psychological, social, environmental, economic, and political empowerment, used in the definition of the conceptual framework of the ZRETP model. Based on this, for each of the five identified empowerment dimensions, the hypotheses assumed direct and positive effects of each dimension on participation (H1–H5), as well as mediating effects of ENE and ECE dimensions in the relationships between psychological and social empowerment and participation (H6–H9). In the next step of the research procedure, EFA is implemented on RETS 2.0, which reveals a modified factor structure that empowers Gen Z, compared to the initially used RETS 2.0, based on which social and psychological empowerment were integrated as a unique socio-psychological factor (SPSE). A four-factor structure for empowering Gen Z (SPSE, ENE, ECE, and PE) was used in the ZRETP model assessment, using PLS-SEM. The model results indicated the irrelevance of PE, and it was excluded from the analysis of the ZRETP model. Finally, measurement and structural model assessments were made for the ZRETP model, including SPSE, ENE, and ECE, and its assumed direct and indirect effects on P. In the proposed research model, separate hypotheses are defined for psychological and social empowerment, based on the initially used RETS 2.0 scale. EFA identified those two factors as integrated SPSE for Gen Z, used in the ZRETP model.

For the purpose of hypothesis testing, results observed for SPSE effects are used for testing both hypotheses, H1 and H2, considering this methodologically acceptable. Observing results for SPSE effects on P, there is evidence of its positive but insignificant direct influence on Gen Z’s participation in sustainable development (β = 0.108; p = 0.253). Following, H1 and H2 are not supported, since the insignificance of SPSE influence was identified. These findings overlap with previous findings of Castillo-Vizuette [43], suggesting that psychological empowerment does not significantly affect attitudes towards ecotourism. In accordance with our findings, also for social empowerment, impacts on sustainable tourism development are identified as weak, positive, but insignificant effects [59]. Contrary to these findings, Gautam and Balla [7] found psychological empowerment as the most important predictor of residents’ support for sustainable tourism development, followed by social empowerment. Similarly, Moreira dos Santos et al. [9] indicated these two factors as significant predictors for the sustainable development of tourism.

The ENE demonstrates positive and significant influences on Gen Z’s participation in sustainable development (β = 0.373, p = 0.000). Its direct influence has the strongest effects on Gen Z’s P. This finding supports H3. Accordingly, environmental empowerment was identified as having positive and significant effects on attitudes about ecotourism [43]. Moreira dos Santos et al. [9] also identified its significant and positive effects. Research findings contradict those of Shafieisabet and Haratifard [24], who found no significant perceived environmental, ecological, or economic impact on participation in sustainable tourism.

For the ECE, direct, significant, and positive influences on Gen Z’s P (β = 0.233, p = 0.004) are confirmed. ECE is a significant predictor for the Gen Z generation and their P, which supports H4. Accordingly, Cahyaningrum et al. [63] indicated that community empowerment through participation in tourism development delivers significant positive economic impacts and also fosters sustainable economic growth by effectively utilizing local resources. Economic empowerment was positively associated with supportive behavior in tourism [61]. For a younger group of residents, personal economic benefits from tourism are identified as a significant predictor of the perceived contribution of sustainable tourism [16].

PE was excluded from the ZRETP model after initial path analysis, taking into account its irrelevance and the problem caused by its presence in the model. The analysis identified its insignificant and negative effects on P, lack of contribution compared to the other empowerment factors for Gen Z, cross-loading problems, and lack of clear distinction from other constructs in the model. Its exclusion from the model is considered justified since it contributes to the clarity and parsimony of the ZRETP model. The decision to exclude PE from the model has important implications for interpreting H5. The hypothesis remained untested, as the construct did not meet the required criteria and was excluded from the model. These findings align with previous research suggesting the influence of political empowerment on support for sustainable tourism development [7,71,72] and on attitudes towards ecotourism [43], with a negative effect on residents’ supportive behavior in tourism [61].

For the purpose of testing the mediating role of ENE and ECE, four further hypotheses (H6–H9) are defined. Separately defined hypotheses for psychological (H6 and H8) and social empowerment (H7 and H9), based on initially used RETS 2.0.

Hypotheses H6 and H8 assumed positive effects of psychological and social empowerment on participation mediated by environmental empowerment. For the purpose of hypothesis testing, results observed for SPSE effects are used for testing both hypotheses, considering this methodologically acceptable. ENE demonstrated a positive and significant mediation effect (β = 0.277; p = 0.000) in the relationship between SPSE and P. These indirect effects are stronger and significant, compared to weaker and insignificant direct effects that SPSE has on P (β = 0.108; p = 0.253), since we have indirect-only mediation [31] (p. 234). Additionally, VAF (Variance Accounted For) is conducted to check the strength of mediation with a value of 0.712 (or 71.2%), indicating very strong partial mediation. This supports the mediation hypotheses H6 and H8, since it is evident that SPSE affects P mostly through ENE, rather than directly. This implies the necessity to include Gen Z residents in different projects and sustainable initiatives and accomplish empowerment through participation. Following this, Maeda & Hirose [73] found that behavioral intention to participate in the waste management planning is determined by personal empowerment expectation and costs. The same authors [74] noted a greater willingness to participate in developing the environmental plan if citizens have a higher expected level of empowerment through their participation, indicating that seeing positive personal benefits of participation leads to increased participation.

To test the mediating role of ECE in the relationships between SPSE and P, we define hypothesis H7 for psychological empowerment and H9 for social empowerment. ECE has a very weak but positive and significant mediating effect (β = 0.113; p = 0.004). Comparing these mediating effects with the direct effects of SPSE on P (β = 0.108; p = 0.253), it is evident that the mediating effect is significant and exceeds the direct effect. The mediated share of the total effects was 51.1% (VAF = 0.051). These results supported H7 and H9, indicating that ECE mediated the relationship between SPSE and P. These findings align with Hsu et al. [75], who noted that perceived economic benefits mediated the effect of environmental sustainability on support for sustainable tourism.

4.7. Discussion and Contribution

Within the observed ZRETP model, the SPSE latent variable has numerous direct and indirect influences (Table A5), contributing to the spread of existing knowledge that placed greater emphasis on economic benefits. This finding aligns with the results of Gautam and Bhalla [7], who identified psychological empowerment as a crucial predictor of support for sustainable tourism development, followed by social empowerment.

Considering the strong indirect and total effect of SPSE (β = 0.558; p = 0.000) on Gen Z’s participation, it confirms that SPSE represents a key theoretical base for understanding its participation in sustainable tourism. The findings align with those of Christens et al. [76], suggesting that increases in psychological empowerment are likely to result from programs or interventions that increase community participation. For adolescents, Messman et al. [77] emphasized that psychological empowerment is related to three positive behaviors: prosocial behavior, providing social support, and making responsible decisions, which are crucial in participating in sustainable tourism.

Notably, SPSE has a direct, strong, and significant total impact on ENE (β = 0.744; p = 0.000). Additionally, ENE has a moderate and significant total effect on Gen Z’s P (β = 0.452; p = 0.000), confirming ENE as a key mediator. Aligning with this, Shafieisabet and Haratifard [24] indicate that the empowerment of local stakeholders positively influences perceived environmental-ecological and socio-ecological impacts. In total, there is a strong and significant influence of SPSE on ECE (β = 0.740; p = 0.000), which is both direct (β = 0.487; p = 0.000) and indirect, implying that ECE is the result of SPSE effects. These findings align with those of Sawangchai et al. [78], suggesting that psychological and social empowerment significantly impact women’s participation in civil society and their entrepreneurial resilience. Khoso et al. [79] demonstrate that psychological and economic empowerment are taking center stage in enhancing women’s developmental participation in tourism development in Pakistan.

Following those mentioned above, this study offers theoretical and practical contributions. The research fills a critical research gap in the literature by exploring empowering factors and their influences on participation, tailored for Gen Z empowerment. This paper’s findings enrich existing knowledge and build upon previous research by creating an integrated empowerment–participation model tailored for Gen Z (ZRETP). This provides a holistic and new perspective in understanding how to motivate young residents to participate in tourism decision-making, which is still an under-researched resident group. This model can be applied in future research to other resident groups, such as women, children, or older residents, who are still marginalized in the context of empowerment and active participation in tourism-related decisions.

The findings also provide practical insights for destination managers and policymakers, highlighting the empowerment factors to enhance the engagement of Gen Z residents in future decision-making for sustainable tourism development. Theoretically confirmed importance of Gen Z’s internal empowerment (evident from SPSE effects) and environmental values (evident from ENE effects) in creating benefits (evident from ECE effects) can guide practitioners in creating sustainable tourism strategies. Observing it in the context of excluded political empowerment from the ZRETP model, the strategy of sustainable tourism should be focused on SPSE and ENE, which motivate Gen Z to participate and lead to economic prosperity. Also, Gen Z does not see classical political channels as a form through which they prefer to participate, indicating the need for creating new approaches for engaging Gen Z in participation and alternative participation channels (digital and social media, volunteering, and community projects related to sustainable development).

5. Conclusions

The residents’ participation is becoming necessary for securing long-term, sustainable tourism development. Participation does not happen automatically and requires genuine empowerment. Just because Generation Z has strong values and exhibits a strong interest in sustainability and social participation does not mean they will be ready or willing to get involved in activities and decision-making related to tourism development. Generation Z could represent an ideal long-term partner for shaping the future of tourism development. Including the voices of the young generation will be challenging, but it is necessary for ensuring meaningful and long-term sustainable tourism development. Empowering Gen Z to participate in tourism decision-making will require a system that enables them to act on their values, contribute to their communities, and help shape the overall future of tourism in their destinations. Intentionally applied and promoted, empowerment can lead to more inclusive and sustainable tourism development, for which Gen Z will play a key role and hold a leading position in shaping the future of tourism.

However, this study has some limitations, from which future research directions can be derived. The research was conducted among students, primarily females, at the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management. The student population is a specific subgroup of Gen Z, with a relatively homogenous socio-economic status and a specific social context. During the study, they have a greater possibility to enrich knowledge related to sustainable development and tourism, compared to some other resident groups. The research was conducted on a student sample within a single national context. Specific characteristics of the student population and one cultural context in which the research was conducted limit the generalizability of the findings. The absence of comparative studies and a cross-cultural perspective limits the possibility of comparing our findings with other destinations and socio-cultural contexts to evaluate the consistency of the ZRETP model. Thus, findings from this research should be interpreted as indicative for Gen Z and not generally applicable to the whole population. Future research should expand the sample, include students from other faculties and nations, and use a more diverse sample of Gen Z residents, ensuring equal representation by gender. Expanding the sample will provide opportunities for comparing the empowering results on participation obtained among different age groups of residents, especially on underexplored resident groups like children, women, or older residents. The research was conducted over a specific time and relates to a particular academic year. Given the dynamics of changes in the destination context and the behavioral characteristics of Gen Z, such research needs to be conducted longitudinally, thereby respecting the continuity of these changes. Some limitations are methodological and related to the use of PLS-SEM in model validation. PLS-SEM implementation in this research is completely justified due to its exploratory nature, model complexity, and predictive nature, which align with the main research objective. Still, it has limitations related to the lack of global fit indices and applicability in strictly theory testing. In future research, the implementation of CB-SEM is recommended, which will enable further validation of the integrated socio-psychological factor, which was validated in this research by EFA, to confirm theoretical validity and assess the robustness of the ZRETP model and measuring invariance between different Gen Z groups. This diversity within Gen Z should be examined in future research by applying multi-group comparisons and testing measurement invariance between Gen Z subgroups defined by gender, socio-economic status, or cultural context. These further studies will contribute to the robustness of the ZRETP model and assure, in general, a more comprehensive understanding of the empowerment–participation relationship among young people in sustainable tourism. The model can also be applied to different destinations (urban, rural, and more or less developed destinations) and compare them. The most comprehensive results will be assured by using both approaches, PLS-SEM and CB-SEM, as two widely used methods of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.; methodology, L.B.; software, L.B.; validation, L.B.; formal analysis, L.B.; investigation, L.B. and I.B.; resources, L.B. and I.B.; data curation, L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B., I.B., and K.Č.; writing—review and editing, L.B., I.B., and K.Č.; visualization, L.B.; supervision, L.B.; project administration, L.B.; funding acquisition, L.B., I.B., and K.Č. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Opatija, University of Rijeka, Croatia (Class: 053-01/25-01/02; Registration number: 2156-18-25-01-01 on [28 January 2025].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to an author’s ORCID. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The Residents Empowerment through Tourism Scale—The RETS 2.0.

Table A1.

The Residents Empowerment through Tourism Scale—The RETS 2.0.

| Item No. | Dimension/Item |

|---|---|

| Environmental Empowerment | |

| ENE1 | Reminds me that I have the obligation to protect my natural surrounding. |

| ENE2 | Makes me want to adopt reuse, reduce, and recycle practices. |

| ENE3 | Provides ways for me to promote environmentally friendly initiatives. |

| ENE4 | Makes me want to protect biodiversity in my place. |

| ENE5 | Reminds me that I have the obligation to preserve our natural heritage. |

| ENE6 | Makes me feel I can contribute to my community’s wellbeing through preservation of physical surrounding. |

| Economic Empowerment | |

| ECE1 | Provides ways for me to use funds allocated from tourism to improve my place. |

| ECE2 | Makes me want to control my available income. |

| ECE3 | Makes me feel I can benefit economically long-term. |

| ECE4 | Provides ways for me to support my family. |

| ECE5 | Makes me feel I can improve my standard of living. |

| ECE6 | Makes me feel I can benefit from tourism even if I am not employed in tourism. |

| Psychological Empowerment | |

| PSE1 | Makes me proud to be a resident in my place. |

| PSE2 | Makes me feel special because people travel to see my country’s unique features. |

| PSE3 | Makes me want to tell others about what we have to offer in my place. |

| PSE4 | Reminds me that I have a unique culture to share with visitors. |

| PSE5 | Makes me want to work to keep my place special. |

| Social Empowerment | |

| SE1 | Makes me feel more connected to my place. |

| SE2 | Fosters the sense of community spirit within me. |

| SE3 | Provides ways for me to get involved in my place. |

| Political Empowerment | |

| PE1 | I have a voice in tourism development decisions in my place. |

| PE2 | I have access to decision-making process when it comes to tourism in my place. |

| PE3 | My vote makes a difference in how tourism is developed in my place. |

| PE4 | I have an outlet to share my concerns about tourism development in my place. |

Source: adapted from [45].

Table A2.

Participation in sustainable tourism development.

Table A2.

Participation in sustainable tourism development.

| Item No. | Item |

|---|---|

| P1 | I am willing to participate in the development of sustainable tourism in my place. |

| P2 | I am willing to adopt sustainable tourism practice in my business and private life. |

| P3 | I am committed to promoting the benefits of sustainable tourism to others. |

| P4 | I am willing to invest time and resources in the development of sustainable tourism in my place. |

Source: adapted from [63].

Appendix B

Table A3.

Factor loadings for ZRETS.

Table A3.

Factor loadings for ZRETS.

| Constructs/ Variables | Mean | St. Dev. | Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPSE | 4.01 | 0.972 | |

| SE1 | 3.96 | 0.993 | 0.787 |

| PSE5 | 4.08 | 0.929 | 0.771 |

| PSE3 | 4.08 | 0.966 | 0.770 |

| PSE4 | 4.12 | 0.917 | 0.753 |

| PSE2 | 4.11 | 0.955 | 0.740 |

| SE2 | 3.91 | 1.007 | 0.713 |

| SE3 | 3.81 | 0.990 | 0.588 |

| PSE1 | 4.00 | 1.019 | 0.571 |

| ENE | 4.04 | 0.915 | |

| ENE2 | 3.97 | 0.920 | 0.808 |

| ENE3 | 3.93 | 0.933 | 0.768 |

| ENE4 | 4.06 | 0.927 | 0.728 |

| ENE1 | 4.03 | 0.911 | 0.726 |

| ENE5 | 4.31 | 0.853 | 0.704 |

| ENE6 | 4.11 | 0.898 | 0.700 |

| EKE1 | 3.85 | 0.963 | 0.531 |

| ECE | 3.75 | 1.029 | |

| ECE3 | 3.59 | 1.043 | 0.774 |

| ECE4 | 3.63 | 1.096 | 0.704 |

| ECE2 | 3.77 | 1.031 | 0.697 |

| ECE5 | 3.92 | 0.969 | 0.649 |

| ECE6 | 3.82 | 1.005 | 0.613 |

| PE | 3.17 | 1.243 | |

| PE3 | 3.09 | 1.256 | 0.852 |

| PE2 | 3.23 | 1.219 | 0.838 |

| PE1 | 3.29 | 1.214 | 0.808 |

| PE4 | 3.05 | 1.281 | 0.769 |

| Total | 3.74 | 1.058 |

Table A4.

Cross-loading for ZRETP.

Table A4.

Cross-loading for ZRETP.

| SPSE | ENE | ECE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPSE | ||||

| SE1 | 0.871 | 0.635 | 0.605 | 0.509 |

| PSE5 | 0.867 | 0.641 | 0.628 | 0.506 |

| PSE3 | 0.865 | 0.616 | 0.634 | 0.495 |

| PSE4 | 0.833 | 0.611 | 0.588 | 0.472 |

| PSE2 | 0.840 | 0.642 | 0.601 | 0.454 |

| SE2 | 0.817 | 0.599 | 0.597 | 0.438 |

| SE3 | 0.755 | 0.565 | 0.594 | 0.413 |

| PSE1 | 0.783 | 0.627 | 0.662 | 0.408 |

| ENE | ||||

| ENE2 | 0.548 | 0.834 | 0.550 | 0.487 |

| ENE3 | 0.596 | 0.851 | 0.576 | 0.506 |

| ENE4 | 0.627 | 0.842 | 0.582 | 0.545 |

| ENE1 | 0.591 | 0.798 | 0.513 | 0.493 |

| ENE5 | 0.672 | 0.843 | 0.558 | 0.520 |

| ENE6 | 0.641 | 0.834 | 0.582 | 0.533 |

| EKE1 | 0.611 | 0.770 | 0.683 | 0.471 |

| ECE | ||||

| ECE3 | 0.550 | 0.522 | 0.837 | 0.436 |

| ECE4 | 0.615 | 0.571 | 0.856 | 0.471 |

| ECE2 | 0.589 | 0.579 | 0.815 | 0.481 |

| ECE5 | 0.686 | 0.674 | 0.858 | 0.507 |

| ECE6 | 0.620 | 0.557 | 0.787 | 0.485 |

| P | ||||

| P1 | 0.498 | 0.553 | 0.488 | 0.880 |

| P2 | 0.491 | 0.566 | 0.498 | 0.863 |

| P3 | 0.421 | 0.500 | 0.442 | 0.843 |

| P4 | 0.533 | 0.535 | 0.574 | 0.910 |

Table A5.

Results of other direct, indirect, and total effects.

Table A5.

Results of other direct, indirect, and total effects.

| β-Values | t-Values | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Other direct effects | |||

| ENE → ECE | 0.340 | 5.701 | 0.000 |

| SPSE → ECE | 0.487 | 8.366 | 0.000 |

| SPSE → ENE | 0.744 | 21.857 | 0.000 |

| Other specific indirect effects | |||

| SPSE → ENE → ECE | 0.253 | 5.432 | 0.000 |

| ENE → ECE → P | 0.079 | 2.378 | 0.017 |

| Total indirect effects | |||

| ENE → P | 0.079 | 2.378 | 0.017 |

| SPSE → ECE | 0.253 | 5.432 | 0.000 |

| SPSE → P | 0.450 | 5.973 | 0.000 |

| Total effects | |||

| ENE → P | 0.452 | 5.560 | 0.000 |

| ENE → ECE | 0.340 | 5.701 | 0.000 |

| SPSE → ECE | 0.740 | 23.634 | 0.000 |

| SPSE → ENE | 0.744 | 21.857 | 0.000 |

| SPSE → P | 0.558 | 11.341 | 0.000 |

References

- Global Development Research Center (GDRC). Charter for Sustainable Tourism. 1995. Available online: https://www.gdrc.org/uem/eco-tour/charter.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Briassoulis, H. Sustainable tourism and the question of the commons. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T. Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D. A flawed implementation of sustainable tourism: The experience of Akamas, Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.; Robson, I. From shareholders to stakeholders: Critical issues for tourism marketers. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Community decision-making participation in development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V.; Bhalla, S. Exploring the relationships among tourism involvement, residents’ empowerment, quality of life and their support for sustainable tourism development. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, E.L.M. Re-examining the participation and empowerment nexus: Applications to community-based tourism. World Dev. Perspect. 2023, 31, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira dos Santos, E.R.; Pereira, L.N.; Pinto, P.; Boley, B.B. Development and validation of the new resident empowerment through tourism scale: RETS 2.0. Tour. Manag. 2024, 104, 104915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.B.; Jamal, T. An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinero, Y.; Prayag, G.; Gómez-Rico, M.; Ramos-Ridao, Á. Generation Z and pro-sustainable tourism behaviors: Internal and external drivers. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 33, 1059–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Seyfi, S.; Elhoushy, S.; Okumus, B.; Woosnam, K.M.; Patwardhan, V. Determinants of Generation Z pro-environmental travel behaviour: The moderating role of green consumption values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 33, 1079–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubíková, Ľ.; Rudý, S. Attitudes of Generation Z towards sustainable behaviour in tourism. TEM J. 2024, 13, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Pongsakornrungsilp, P.; Klamsaengsai, S.; Ketkaew, K.; Tonsakunthaweeteam, S.; Li, L. Influence of creative tourist experiences and engagement on Gen Z’s environmentally responsible behavior: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, H. Influences on tourism development decision making: Coastal local government areas in Eastern Australia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bašan, L.; Perušina, I.; Ham, M. Improving the perceived contribution of sustainable development through the residents’ empowerment and support for tourism development: A different age group context. J. Econ. Bus. 2024, 42, 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, B.K.; Cheung, L.T.; Hui, D.L. Community participation in the decision-making process for sustainable tourism development in rural areas of Hong Kong, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C.; Wang, J.T.M.; Wu, M.R. Community participation as a mediating factor on residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development and their personal environmentally responsible behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 1764–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkić, D.; Primužak, A.; Erdeljac, N. Sustainable tourism development of coastal destination—The role and the significance of local residents. In Proceedings of the ToSEE–Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe, Opatija, Croatia, 16–18 May 2019; Volume 5, pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]