Can Removing Policy Burdens Improve SOEs’ ESG Performance? Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Regarding the research content, this paper contributes to the existing literature on business burdens by addressing a gap in the research concerning the economic implications of RPB on SOEs. Previous studies have primarily concentrated on the economic impacts of privatization and mixed-ownership reform in SOEs. This article, starting from the background of the long-term policy burdens borne by SOEs, empirically tests the ESG effect of RPB, and provides new empirical evidence for SOEs to achieve comprehensive ESG improvements through reform.

- (2)

- Regarding research subjects, this study expands the boundary of ESG research on SOEs in emerging economies. Previous research has predominantly focused on the context of Western market economies, with limited attention given to the specificities of ESG practices within SOEs in emerging markets. This study specifically examines Chinese SOEs, combining their characteristics of ‘heavy policy burdens and unique institutional environments’ to reveal the mechanism of promoting ESG through RPB. It provides a reference for other emerging economies to advance ESG practices through SOE reform.

- (3)

- From a research perspective, this paper provides a new entry point for macro-policy interventions to explore the influencing factors of corporate ESG performance. Existing research has largely focused on internal and external factors such as institutional policies, market pressures, industry characteristics, and corporate governance [6,28,29,30]. However, it overlooks the fundamental logic by which institutional reforms like RPB activate the initiative for ESG practices within SOEs by resolving their inherent constraints. This paper takes the HPWET-based natural experiment to reveal the path of RPB’s role in the collaborative improvement of ESG, providing a scientific basis for the government to formulate policies related to SOE reform and sustainable development.

2. Literature Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Literature Background

2.1.1. SOE Reform

2.1.2. The Factors Influencing Corporate ESG Performance

2.2. Policy Background

2.3. Research Hypothesis

3. Methods and Variables

3.1. Model Construction

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: ESG Performance (ESG)

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Sample Selection

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

4. Empirical Results and Mechanisms

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

4.2. Robustness Test Results

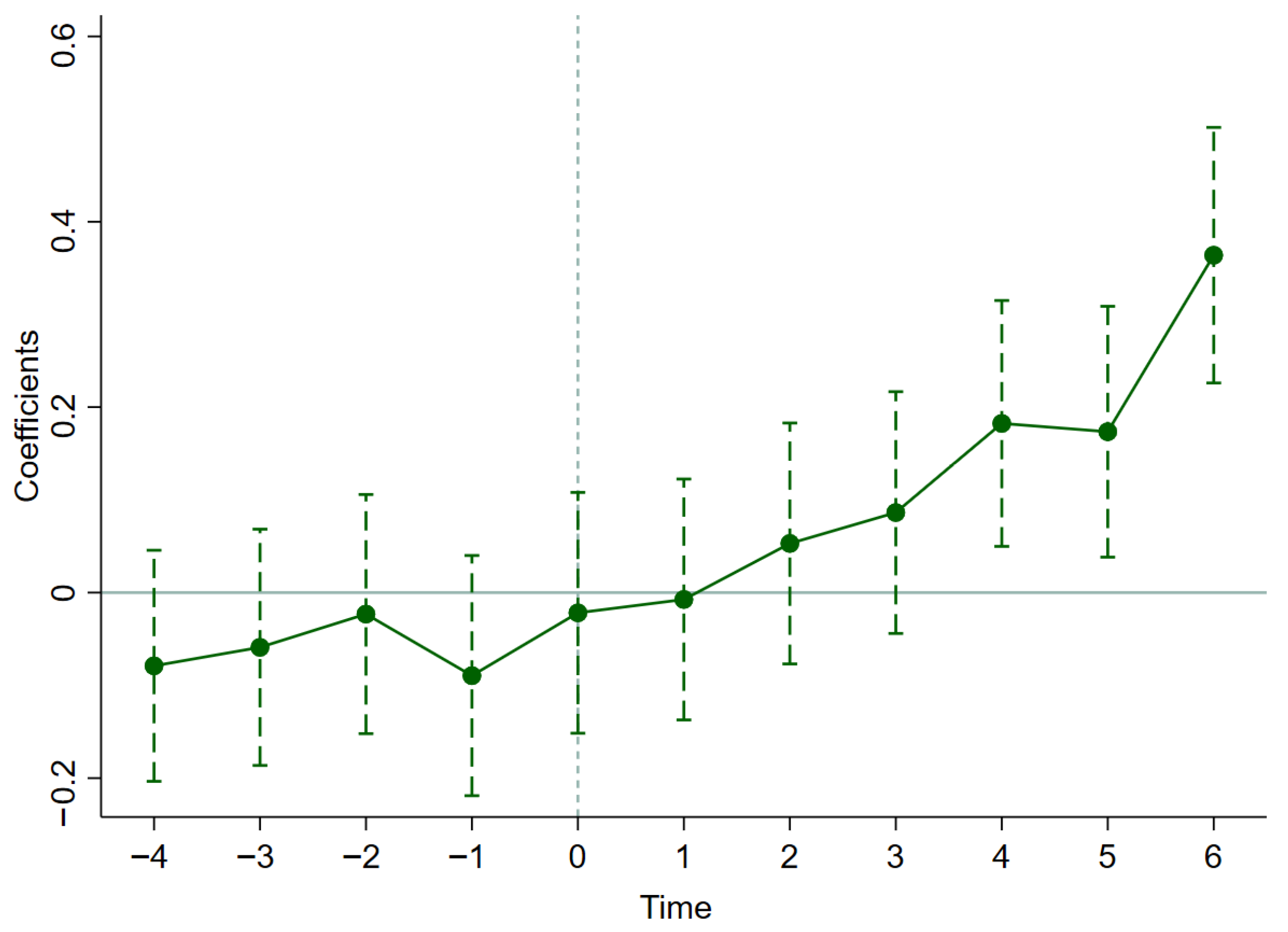

4.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

4.2.2. Placebo Test

4.2.3. Endogeneity Test

4.2.4. Additional Robustness Tests

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

4.3.1. Green Innovation Level

4.3.2. Political Connection

4.3.3. Corporate Governance Environment

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Size of Enterprises

5.2. Level of Technological Marketization

5.3. Industry Pollution Level

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Policy Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SOE | State-owned enterprise |

| HPWET | Transfer the social functions of heating, power, water, and estate |

| DID | Difference-in-differences |

| RPB | Removing policy burdens |

| ESG | Environmental, social and governance |

| IV-2SLS | Instrumental variables-two stage least square |

| 2016 Opinions | The Guiding Opinions on the Separation and Transfer of ‘Heating, Power, Water, and Estate’ in Family Areas of Employees of SOEs in June 2016 |

References

- Pimenta, A.; Kamruzzaman, L.(Md). Assessing the Comprehensiveness and Vertical Coherence of Climate Change Action Plans: The Case of Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and Social Responsibility: A Review of ESG and CSR Research in Corporate Finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, J. Can Green Credit Policies Improve Corporate ESG Performance? Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 2678–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cezarino, L.O.; Liboni, L.B.; Hunter, T.; Pacheco, L.M.; Martins, F.P. Corporate Social Responsibility in Emerging Markets: Opportunities and Challenges for Sustainability Integration. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Noor, A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Financial Constraints: The Role of Insider and Institutional Ownership. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, T.Y.; Amran, A.; Teoh, A.P. Factors Influencing ESG Performance: A Bibliometric Analysis, Systematic Literature Review, and Future Research Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Lockhart, J.; Bathurst, R. The Institutional Analysis of CSR: Learnings from an Emerging Country. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2021, 46, 100752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Climate Change and Low-Carbon Transition Policies in State-Owned Enterprises; OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. Fiscal Monitor, April 2020: Policies to Support People During the COVID-19 Pandemic; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-5135-3751-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ellimäki, P.; Aguilera, R.V.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E.; Aragón-Correa, J.A. The Link between Foreign Institutional Owners and Multinational Enterprises’ Environmental Outcomes. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 910–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C.C.; Vermaelen, T. Internal Regulation: The Effects of Government Ownership on the Value of the Firm. J. Law Econ. 1986, 29, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewenter, K.L.; Malatesta, P.H. State-Owned and Privately Owned Firms: An Empirical Analysis of Profitability, Leverage, and Labor Intensity. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Grosman, A.; Megginson, W.L. A Review of the Internationalization of State-Owned Firms and Sovereign Wealth Funds: Governments’ Nonbusiness Objectives and Discreet Power. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 78–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, B.; Milgrom, P. Multitask Principal–Agent Analyses: Incentive Contracts, Asset Ownership, and Job Design. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1991, 7, 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y. State-Owned Enterprise Reform in China: The New Structural Economics Perspective. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2021, 58, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornai, J. The Soft Budget Constraint. Kyklos 1986, 39, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Cai, F.; Li, Z. Competition, Policy Burdens, and State-Owned Enterprise Reform. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.Y.; Li, Z. Policy Burden, Privatization and Soft Budget Constraint. J. Comp. Econ. 2008, 36, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Cui, H. Will unloading burden in state-owned enterprises improve innovation? A quasi-natural experiment based on the reform of ‘Heating, Power, Water and Estate’. Reform 2023, 4, 111–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, X. Separating Policy Burdens: Quantifying the Economic Benefits and Mechanisms in China’s State-Owned Enterprises. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Zeng, J.; Liao, F.; Huang, J. Policy Burden of State-Owned Enterprises and Efficiency of Credit Resource Allocation: Evidence from China. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211005467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszak, P.; Szarzec, K. The Scale and Financial Performance of State-Owned Enterprises in the CEE Region*. Acta Oeconomica 2019, 69, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Guo, B. Does the Mixed-Ownership Reform of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises Improves Their Total Factor Productivity? Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 82, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Li, C.; Li, N.; Khan, M.A.; Sun, X.; Khaliq, N. Can Mixed-Ownership Reform Drive the Green Transformation of SOEs? Energies 2021, 14, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. Enterprise Reform in China: Agency Problems and Political Control. Econ. Transit. 1996, 4, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Wu, J. China’s Transition to a Market Economy: How Far Across the River? Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.P.H.; Wong, T.J.; Zhang, T. Institutions and Organizational Structure: The Case of State-Owned Corporate Pyramids. J. Law Econ. Organ. 2012, 29, 1217–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Lorenzo, D.M.; Liberatore, G.; Mazzi, F.; Terzani, S. Role of Country- and Firm-Level Determinants in Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Yang, J.J. Foreign Institutional Investor Herding and ESG Ratings. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2025, 90, 102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Mo, Y. Management Myopia and Corporate ESG Performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 92, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, S.G.; Musacchio, A. State Ownership Reinvented? Explaining Performance Differences between State-Owned and Private Firms. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2018, 26, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megginson, W.L.; Netter, J.M. From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privatization. J. Econ. Lit. 2001, 39, 321–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, I.; Ma, X.; Mizobata, S. Ownership Structure and Firm Performance in Emerging Markets: A Comparative Meta-Analysis of East European EU Member States, Russia and China. Econ. Syst. 2022, 46, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Li, C.; Sun, X.; Khan, M.A.; Khaliq, N. Does Mixed-Ownership Reform Affect SOEs’ Competitive Strategies? Eng. Econ. 2024, 35, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, H.; Li, T.; Toolsema, L.A. Corporate Social Responsibility Investment and Social Objectives: An Examination on Social Welfare Investment of Chinese State Owned Enterprises. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2009, 56, 267–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Gao, Z.; Tan, J.; Sun, W.; Shi, F. Does the Mixed Ownership Reform Work? Influence of Board Chair on Performance of State-Owned Enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.L.; Gao, Z.B.; Zhang, K.Z. Policy Burdens and the Leverage of State-Owned Enterprises: The Mediate Effect of Soft Budget Constraint. Ind. Econ. Rev. 2019, 5, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yu, M. The Nature of Ownership, Marketization Process and Enterprise Risk-Taking. China Ind. Econ. 2012, 12, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y.W. Policy Burdens and Audit Fees: Evidence Based on Redundant Employees. Audit. Econ. Res. 2020, 35, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, F.; Sun, Y.; Xu, S. Do the Policy Burdens of State-Owned Enterprises Affect the Efficiency of Resource Allocation of Tax Incentives? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 75957–75972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Pan, C.H.; Statman, M. Why Do Countries Matter so Much in Corporate Social Performance? J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 41, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzani, S.; Turzo, T. Religious Social Norms and Corporate Sustainability: The Effect of Religiosity on Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, G.; Cupertino, S.; Schiuma, G.; Troise, C. Investigating How Mandatory Sustainability Reporting Influences Corporate Governance Effects on ESG Performance: From Obligation to Impact for Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 6261–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopita, A.; Petrou, Z. Does Analyst ESG Experience Matter? Br. Account. Rev. 2024, 101438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, Y. Can Industry Competition Stimulate Enterprises ESG Performance? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 104, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, R. Corporate Socially Responsible Investments: CEO Altruism, Reputation, and Shareholder Interests. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.; Luu, B.V. International Variations in ESG Disclosure—Do Cross-Listed Companies Care More? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 75, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, N.; Sebastianelli, R. Transparency among S & P 500 Companies: An Analysis of ESG Disclosure Scores. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Tu, Y.; Li, Z. Enterprise Digital Transformation and ESG Performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, Y. Equity Incentives and ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, H. The Impact of Carbon Emission Reduction Policies on Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Low-Carbon City Pilots. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Cheng, B. Does Environmental Regulation Affect Firms’ ESG Performance? Evidence from China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 2004–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X. Does China’s National Carbon Market Play a Role? Evidence from Corporate ESG Performance. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, X. Tax Burden and Enterprises’ ESG Performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 103, 104223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The Role of Green Finance in Attaining Environmental Sustainability within a Country’s ESG Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tang, Q. Mandatory Carbon Reporting, Voluntary Carbon Disclosure and ESG Performance. Pac. Account. Rev. 2023, 35, 534–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shen, Z. The Impact of Green Public Procurement on Corporate ESG Performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, P.; Luo, L. How Does Environmental Regulation Affect Corporate Green Innovation: A Comparative Study between Voluntary and Mandatory Environmental Regulations. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2024, 26, 130–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicuonzo, G.; Donofrio, F.; Ranaldo, S.; Dell’Atti, V. The Effect of Innovation on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Practices. Medar 2022, 30, 1191–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Román, J.A.; Romero, I. Determinants of Innovativeness in SMEs: Disentangling Core Innovation and Technology Adoption Capabilities. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 11, 543–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. Research on Different Modes of Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction: A Differential Game Model Based on Carbon Trading Perspective. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W. Institutional Logics. Sage Handb. Organ. Institutionalism 2008, 840, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.P.H.; Wong, T.J.; Zhang, T. Politically Connected CEOs, Corporate Governance, and Post-IPO Performance of China’s Newly Partially Privatized Firms. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 84, 330–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentsch, C.; Finger, M. Yes, No, Maybe: The Ambiguous Relationships Between State-Owned Enterprises and the State. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2015, 86, 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; ISBN 0-521-15174-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Geng, H. The Impact of CEO Reputation on ESG Performance in Varying Managerial Discretion Contexts. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 70, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, H.; Koirala, S.; Luo, D.; Rao, S. Do Titans Deliver the ESG Promise? Societal Recognition and Responsible Corporate Decisions. Br. J. Manag. 2025, 36, 885–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, M.; Lagasio, V. Do Corporate Governance Frameworks Affect Sustainability Reporting? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 3928–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erben Yavuz, A.; Kocaman, B.E.; Doğan, M.; Hazar, A.; Babuşcu, Ş.; Sutbayeva, R. The Impact of Corporate Governance on Sustainability Disclosures: A Comparison from the Perspective of Financial and Non-Financial Firms. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagasio, V.; Cucari, N. Corporate Governance and Environmental Social Governance Disclosure: A Meta-analytical Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-J.; Oh, S.-G.; Lee, H.-Y. The Association between Outside Directors’ Compensation and ESG Performance: Evidence from Korean Firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, P.; Arduino, F.R.; Bruno, E.; Vento, G.A. On the Road to Sustainability: The Role of Board Characteristics in Driving ESG Performance in Africa. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 95, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, M.; Martinez-Blasco, M.; Cuadros, J.; Sanz, F.P. Environmental Performance and Firm Value: The Moderating Role of ESG-Executive Compensation. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 6215–6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fu, X.; Fu, X. Varieties in State Capitalism and Corporate Innovation: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhu, B.; Sun, Y. Digitalization Transformation and ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T. Mediating effects and moderating effects in causal inference. Chin. Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Liu, K.; Tao, Y.; Ye, Y. Digital Finance and Corporate ESG. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Tian, G. Corporate Sustainability and Trade Credit Financing: Evidence from Environmental, Social, and Governance Ratings. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1896–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Z.; Li, Z.; Mao, T.; Yoon, A. Global versus Local ESG Ratings: Evidence from China. Account. Rev. 2025, 100, 161–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Supply Chain Digitalization and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Supply Chain Innovation and Application Pilot Policy. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, J. New Ambient Air Quality Standards, Human Capital Flow, and Economic Growth: Evidence from an Environmental Information Disclosure Policy in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big Bad Banks? The Winners and Losers from Bank Deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, Q.; Tao, Y. Does SASAC Boost the Innovation of State-Owned Enterprises? Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2024, 87, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R.; Gatti, R. Decentralization and Corruption: Evidence across Countries. J. Public Econ. 2002, 83, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwani, M. Transforming Governance Into Social Value: The Critical Role of Board Culture Diversity and Anti-Corruption Policies in Affecting Corporate Social Performance in G20 Countries. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 2964–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, N.; Su, W.; Zhou, H. Green Innovation and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 95, 103461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Luo, W.; Chen, Z.; Feng, Y. Intellectual Property Protection and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2025, 31, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ma, L. Substantive Green Innovation or Symbolic Green Innovation: The Impact of Fintech on Corporate Green Innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 63, 105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.; Neves, M.E.; Vieira, E. Bridging Governance Gaps: Politically Connected Boards, Gender Diversity and the ESG Performance Puzzle in Iberian Companies. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2025, 31, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Kong, X.; Zhou, J. Corporate Political Connection, Rent Seeking and Government Procurement Order. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 103, 104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Zheng, Y. Do Political Connections Stifle Firm Innovation? Natural Experimental Evidence from China’s Anti-Corruption Campaigns. Strateg. Manag. J. 2025, 46, 1183–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sarto, N. Corporate Governance and ESG Controversies: Navigating Risk-Taking in Banks. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 4541–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, J. Executive Educational Background, Corporate Governance and Corporate Default Risk. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Li, C.; Xiong, X. Innovation and Environmental Total Factor Productivity in China: The Moderating Roles of Economic Policy Uncertainty and Marketization Process. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 9558–9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zeng, T.; Li, C. Behavior Decision of Top Management Team and Enterprise Green Technology Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, J. Can Urban Digital Intelligence Transformation Promote Corporate Green Innovation? Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, M.; Feng, Z.; Bu, Y. Digital Inclusive Finance Enabling Green Pathways for Heavily Polluting Enterprises to Achieve Environmental Legitimacy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curi, C.; Mancuso, P.; Scarpa, A. State-Owned Enterprises: A Bibliometric Review and Research Agenda. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 106749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong Phuong, N.; Dinh Khoi Nguyen, T.; Phuoc Vu, H. Politics and Institution of Corporate Governance in Vietnamese State-Owned Enterprises. MAJ 2020, 35, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zeng, S.; Sun, D.; Lin, J. Mixed-Ownership Reform and Innovation: An Examination of State-Owned Enterprises. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 14450–14471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xu, J. Analysis of Residents’ Livelihoods in Transformed Shantytowns: A Case Study of a Resource-Based City in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z. Greening through Social Trust? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2023, 66, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Symbol | Variable Name | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ESG | Environment, society, and governance | SINO ESG Rating Values: the evaluation system is a 9-point scale of AAA-C. Points 1 to 9 are allocated in the order of C to AAA, and the average value is taken each year. |

| did | Staggered difference-in-differences variable | Whether the enterprise has implemented HPWET in the current year, implementation is 1, otherwise 0. |

| Size | Enterprise size | The natural logarithm of the enterprise’s total assets at the end of the year. |

| Age | Enterprise age | The logarithm of the listing year of the enterprise plus 1. |

| Lev | Asset–liability ratio | The ratio of total liabilities to total assets. |

| ROA | Return on total assets | The ratio of net profit to total assets. |

| FCF | Free cash flow | Enterprise free cash flow divided by total assets. |

| Fixed | Fixed asset ratio | The total assets divided by operating income. |

| Top 10 | Ownership concentration | Shareholding of top ten shareholders. |

| Separation | Degree of separation between the two rights | The difference between the control rights and ownership of an enterprise. |

| Stock Code | Stock Name | Announcement | Pub Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 000657 | China Tungsten and Hightech Materials Co., Ltd., Zhuzhou, China | Announcement on the Separation and Transfer of Power Supply and Water Supply for the HPWE of the Subsidiary Company | 31 August 2017 |

| 601006 | Datong-Qinhuangdao Railway Co., Ltd., Datong, China | Announcement on the Separation and Transfer of HPWE | 11 July 2018 |

| 002267 | China Shaanxi Provincial Natural Gas Co., Ltd., Xi’an, China | Announcement on Receiving the Subsidy Funds for the Separation and Transfer of HPWE in the Staff Residential Areas of Provincial SOEs | 19 September 2018 |

| 600546 | China Shanxi Coal International Energy Group Co., Ltd., Taiyuan, China | Announcement on the Separation and Transfer of Social Functions of the HPWE of Subordinate Enterprises and Other Enterprises | 31 January 2019 |

| Variables | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 9917 | 4.337 | 1.069 | 1.000 | 8.500 |

| did | 9917 | 0.141 | 0.348 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Size | 9917 | 23.150 | 1.483 | 20.304 | 27.269 |

| Age | 9917 | 2.876 | 0.418 | 1.386 | 3.466 |

| Lev | 9917 | 0.518 | 0.198 | 0.093 | 0.941 |

| ROA | 9917 | 0.041 | 0.053 | −0.149 | 0.217 |

| FCF | 9917 | 0.012 | 0.082 | −0.303 | 0.213 |

| Fixed | 9917 | 2.491 | 2.167 | 0.342 | 12.960 |

| Top10 | 9917 | 0.573 | 0.152 | 0.249 | 0.922 |

| Separation | 9917 | 4.441 | 7.411 | 0.000 | 28.136 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | ESG | ESG | Bloomberg ESG | |

| did | 0.309 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.793 *** |

| (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.033) | (0.285) | |

| Size | 0.331 *** | 0.362 *** | 1.839 *** | |

| (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.213) | ||

| Age | −0.052 | 0.389 *** | 0.891 | |

| (0.034) | (0.079) | (0.808) | ||

| Lev | −0.992 *** | −1.088 *** | −5.360 *** | |

| (0.074) | (0.084) | (0.908) | ||

| ROA | −0.138 | −0.768 *** | 1.736 | |

| (0.188) | (0.198) | (1.998) | ||

| FCF | 0.527 *** | 0.606 *** | 0.835 | |

| (0.095) | (0.096) | (0.898) | ||

| Fixed | −0.026 *** | −0.035 *** | −0.066 | |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.080) | ||

| Top10 | −0.400 *** | −0.385 *** | −0.439 | |

| (0.104) | (0.120) | (1.181) | ||

| Separation | −0.003 * | −0.003 | 0.052 *** | |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.020) | ||

| Id FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| N | 9917 | 9917 | 9917 | 4978 |

| R2 | 0.014 | 0.064 | 0.081 | 0.714 |

| Variables | Nearest Neighbor Matching | Radius Matching | Kernel Matching |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| did | 0.100 ** | 0.119 *** | 0.119 *** |

| (0.042) | (0.031) | (0.031) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Id FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3683 | 8393 | 8390 |

| R2 | 0.107 | 0.085 | 0.085 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| did | ESG | |

| lncases (IV) | 2.671 *** | |

| (0.543) | ||

| did | 1.148 ** | |

| (0.607) | ||

| Control | Yes | Yes |

| Year/Id FE | Yes | Yes |

| Under-identification test | Anderson canon. corr. LM statistic: 24.118 *** | |

| Weak identification test | Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic: 24.150 | |

| N | 6867 | 6867 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remove Samples of Starting HPWET in 2022 | Add Control Variables | Province and Year Interaction Fixed Effect | |

| Variables | ESG | ESG | ESG |

| did | 0.096 *** | 0.135 *** | 0.189 *** |

| (0.033) | (0.031) | (0.035) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Id FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | No |

| Province × Year FE | No | No | Yes |

| N | 7630 | 9156 | 9917 |

| R2 | 0.074 | 0.082 | 0.610 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIP | FR&D | PC | Governance | |

| did | 0.073 *** | 0.082 ** | −0.372 * | 0.060 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.037) | (0.204) | (0.015) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Id FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 9156 | 5872 | 4764 | 8855 |

| R2 | 0.036 | 0.436 | / | 0.147 |

| Variables | ESG Performance of SOEs (ESG) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of Enterprises | Technological Marketization | Industry Pollution Level | |||||

| Small | Medium | Large | High | Low | Heavily | Lightly | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| did | 0.101 | 0.005 | 0.172 *** | 0.321 *** | −0.073 | 0.085 | 0.189 *** |

| (0.076) | (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.048) | (0.057) | (0.042) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Id FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2474 | 3313 | 4079 | 5277 | 4514 | 2869 | 6876 |

| R2 | 0.710 | 0.699 | 0.646 | 0.613 | 0.692 | 0.061 | 0.093 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, P.; Xu, J. Can Removing Policy Burdens Improve SOEs’ ESG Performance? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188315

Zhao P, Xu J. Can Removing Policy Burdens Improve SOEs’ ESG Performance? Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188315

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Peiyu, and Jiajun Xu. 2025. "Can Removing Policy Burdens Improve SOEs’ ESG Performance? Evidence from China" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188315

APA StyleZhao, P., & Xu, J. (2025). Can Removing Policy Burdens Improve SOEs’ ESG Performance? Evidence from China. Sustainability, 17(18), 8315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188315