Unlocking ESG Performance: How Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors Enhance Corporate Sustainability in China’s Capital Markets

Abstract

1. Introduction

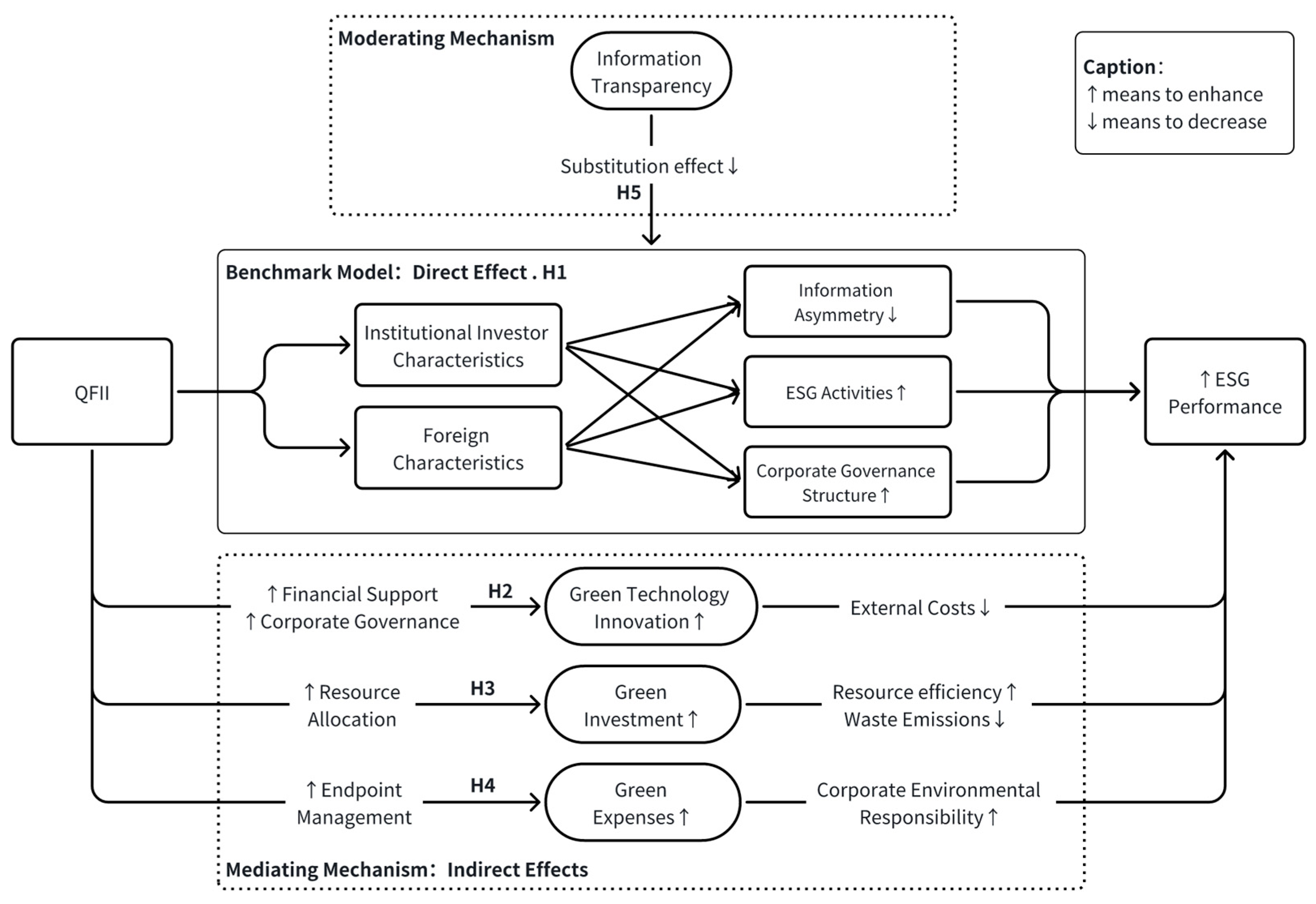

2. Research Hypotheses

2.1. QFII Shareholding and Corporate ESG Performance

2.2. Mediating Mechanism of Green Technology Innovation

2.3. Mediating Mechanism of Green Investment

2.4. Mediating Mechanism of Green Expenses

2.5. Moderating Mechanism of Information Transparency

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Construction

3.1.1. Baseline Model

3.1.2. Mediation Effect Model

3.1.3. Moderation Effect Model

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Explained Variables

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Mediating Variables

Green Technology Innovation

Green Investment

Green Expenses

3.2.4. Moderating Variables

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Sample Selection and Data Sources

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Baseline Model Regression

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Alternative ESG Measurement

4.3.2. Lagged Dependent Variable Analysis

4.3.3. Alternative Proxy for QFII Investment

4.3.4. Extended Fixed-Effects Specifications

4.4. Addressing Endogeneity

4.4.1. Heckman Two-Stage Estimation

4.4.2. Instrumental Variable Approach: GMM Estimation

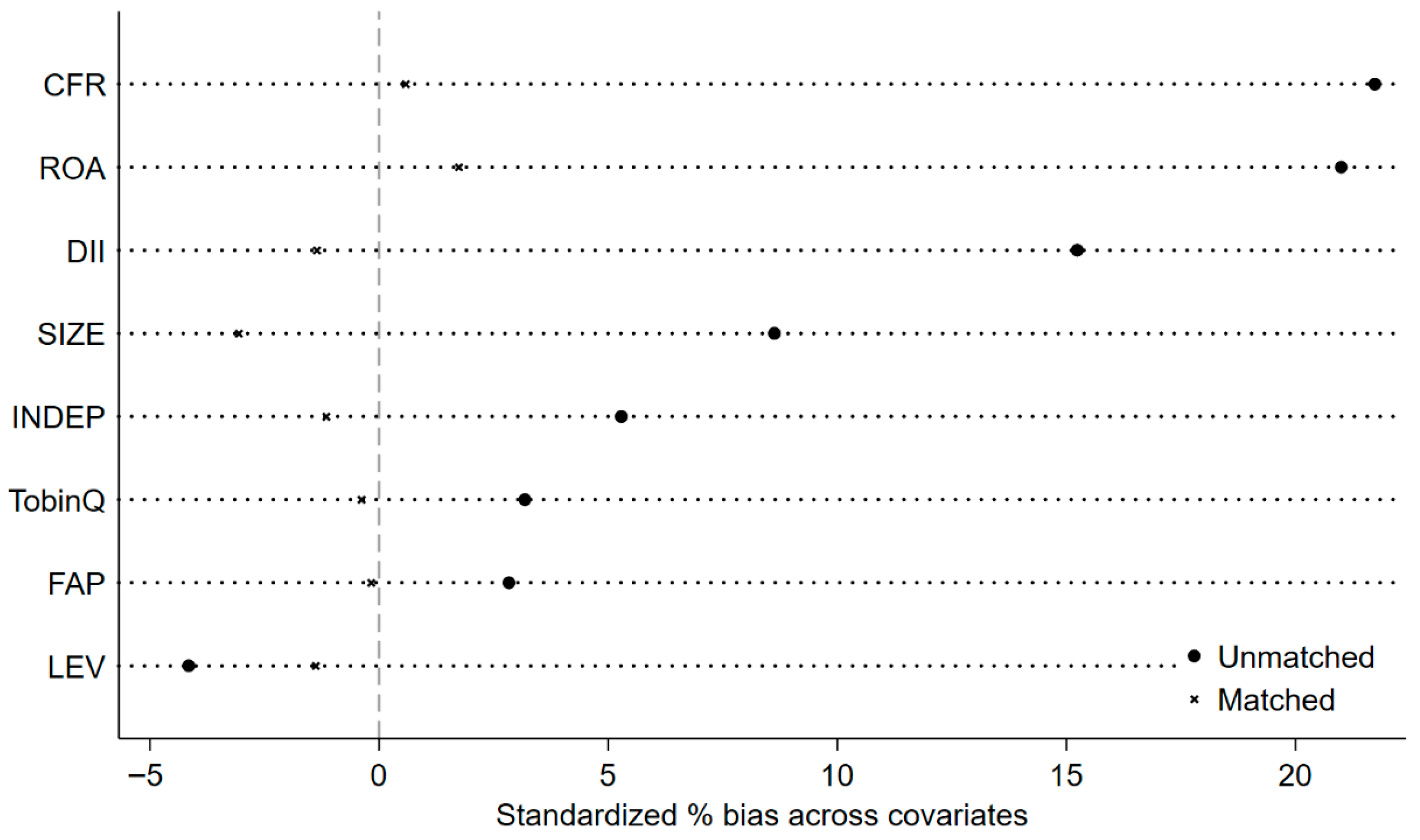

4.4.3. Propensity Score Matching

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

4.5.1. Mediating Effects

Mediating Effect of Green Technology Innovation

Mediating Effect of Green Investment

Mediating Effect of Green Expenses

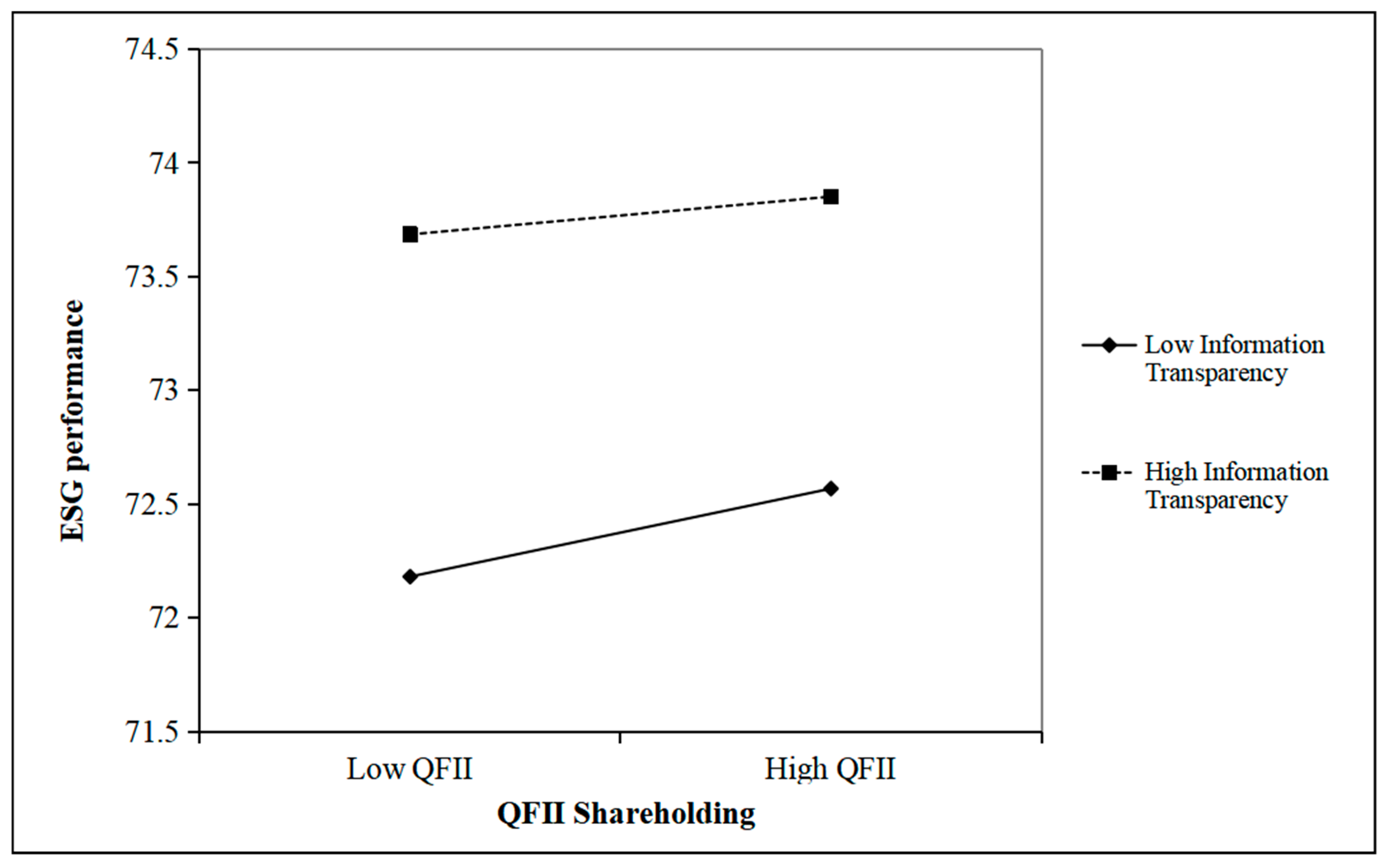

4.5.2. Moderating Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Proposals

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Zhong, A. Stock Market Reaction to Mandatory ESG Disclosure. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirveli, E.; Ortiz-Martínez, E.; Marín-Hernández, S.; Thompson, P. Influencing Sustainability: The Role of Lobbyist Characteristics in Shaping the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 16, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Xu, H.; Chen, J. Can ESG Integration Enhance the Stability of Disruptive Technology Stock Investments? Evidence from Copula-Based Approaches. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wan, D. Stock Market Openness and ESG Performance: Evidence from Shanghai-Hong Kong Connect Program. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.S.; Orsato, R.J. Testing the Institutional Difference Hypothesis: A Study about Environmental, Social, Governance, and Financial Performance. Bus. Strat. Env. 2020, 29, 3261–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, B. The Influence of Foreign Institutional Investors on Audit Fees: Evidence from Chinese Listed Firms. Account. Forum 2024, 48, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Wu, T.; Zhou, D. The Influence of Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors on Internal Control Quality: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 78, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Ren, G.; Liu, L. Returnee Directors and Corporate Environmental Investment: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, D.; Yoshikawa, T. The Differential Effect of Regulatory Signals on Shareholder Dissent: The Case of Shareholder Voting in Director Elections. Corp. Gov. 2025, 33, 1107–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Shi, X.Y. Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors and Corporate Innovation: From the Perspective of Corporate Governance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1005409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Pan, X.; Ma, S. The Effects of Institutional Investors and Their Contestability on Firm Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Listed Firms. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Wu, Q.; Xiong, D.; Zhu, S. How Foreign Institutional Investors’ Ownership Affects Stock Liquidity? Evidence from China. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241260509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Xiong, L.; Xiao, L.; Bai, M. The Effect of Overseas Investors on Local Market Efficiency: Evidence from the Shanghai/Shenzhen–Hong Kong Stock Connect. Financ. Innov. 2023, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, B.; Li, X. Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 101, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Jiang, P.; Elamer, A.A. Revolutionizing Green Business: The Power of Academic Directors in Accelerating Eco-innovation and Sustainable Transformation in China. Bus. Strat. Env. 2024, 33, 5051–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, L.; Cai, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Q. Fiscal & Tax Incentives, ESG Responsibility Fulfillments, and Corporate Green Innovation Performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Hu, X.; Li, Y. Do Tax Incentives Matter in Promoting Corporate ESG Performance toward Sustainable Development? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Yu, J. Striving for Sustainable Development: Green Financial Policy, Institutional Investors, and Corporate ESG Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1177–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; He, Y.; Zeng, L. Can Green Finance Improve the ESG Performance? Evidence from Green Credit Policy in China. Energy Econ. 2024, 137, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; He, R. The Impact of Carbon Emissions Trading Policy on the ESG Performance of Heavy-Polluting Enterprises: The Mediating Role of Green Technological Innovation and Financing Constraints. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xue, R.; Wang, S.; Du, M. Does the Expansion of Local Government Debt Affect the ESG Performance of Enterprises? Evidence From China. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241291307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Xu, X. The Impact of Local Debt Management on Corporate ESG Performance: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the New Budget Law. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 106716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Guo, X.; Yue, P. Media Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Pan, Y. The Spillover Effect of ESG Disclosure Quality: Evidence from Major Customers. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Uncertainty Is a Panacea or a Poison? Exploring the Effect of Economic Policy Uncertainty on Corporate Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosure. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 3528–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakah, E.J.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Abdullah, M.; Ji, Q.; Sulong, Z. Monetary Policy Uncertainty and ESG Performance across Energy Firms. Energy Econ. 2024, 136, 107699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Wen, J.; He, W.; Chen, Y.-E.; Wang, Y.-P. Capital Market Opening and ESG Performance. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2023, 59, 3866–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qi, J.; Zhuang, H. Monitoring or Collusion? Multiple Large Shareholders and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Huang, Y.; Lv, Y. Non-state Shareholder Governance and Corporate Sustainability: Evidence from Environmental, Social and Governance Ratings. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucari, N.; Falco, S.E.D.; Orlando, B. Diversity of Board of Directors and Environmental Social Governance: Evidence from Italian Listed Companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempere, J.; Abdalla, S. The Impact of Women’s Empowerment on the Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasGupta, R. Financial Performance Shortfall, ESG Controversies, and ESG Performance: Evidence from Firms around the World. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Sheng, Z.; Appolloni, A.; Shahzad, M.; Han, S. Digital Transformation, ESG Practice, and Total Factor Productivity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4547–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, J. Digital Transformation, Financing Constraints, and Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 3189–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, Y. A Study on the Impact of Digital Transformation on Corporate ESG Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N. Research on the impact of foreign institutional investors’ shareholdings on ESG performance of firms. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 1–18. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1567.G3.20241206.1638.009 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Han, H. Does Increasing the QFII Quota Promote Chinese Institutional Investors to Drive ESG? Asia Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2023, 30, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, L. Corporate Strategic Radicality, Digital Transformation, and ESG Performance: Moderating Effect of Corporate Life Cycle Stage. Soft Sci. 2024, 38, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftahurrohman; Kusumo, H.; Munifah. Corporate Governance and Firm Performance: The Role of Shareholder Activism in Emerging Markets. J. Manag. Inform. 2024, 3, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajzik, J.; Havranek, T.; Irsova, Z.; Novak, J. Does Shareholder Activism Create Value? A Meta-Analysis. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2025, 33, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Elmaghrabi, M.E. Investment Horizons and ESG Decoupling: Distinct Roles of Long-Term and Short-Term Institutional Investors. Econ. Lett. 2025, 247, 112207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q. ESG Disclosure, Institutional Investor Preferences and Firm Value. Front. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 13, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Fu, W.; Lu, T. Capital Market Opening and Corporate Environmental Performance: Empirical Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Chengshu, W. Company ESG Performance and Institutional Investor Ownership Preferences. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 33, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, P.; Wu, T. Do Foreign Institutional Investors Drive Corporate Social Responsibility? Evidence from Listed Firms in China. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2021, 48, 338–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Financing Decisions: A Literature Review. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2017, 42–43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Du, Y.; Hansen, J.Ø. Foreign Institutional Investors and Dividend Policy: Evidence from China. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, R.U. Sustainability Economics: Where Do We Stand? Ecol. Econ. 2008, 67, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Ling, X. QFII Shareholding and Enterprise Green Technology Innovation. J. Technol. Econ. 2024, 43, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Casciello, R.; Santonastaso, R.; Prisco, M.; Martino, I. Green Innovation and Financial Performance. The Role of R&D Investments and ESG Disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5372–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukthuanthong, K.; Turtle, H.; Walker, T.; Wang, J. Litigation Risk and Institutional Monitoring. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 45, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.A.; Nimmanunta, K. Conventional versus Green Investments: Advancing Innovation for Better Financial and Environmental Prospects. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2023, 13, 1153–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Duan, K.; Ibrahim, H. Green Investments and Their Impact on ESG Ratings: An Evidence from China. Econ. Lett. 2023, 232, 111365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, X. Can Corporate Green Investment and Green Expenses Improve Operating Performance?—An Empirical Analysis Based on EBM and Panel Tobit Model. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y. Research on Mechanism of Digital Finance Improving Corporate ESG Performance: Based on “Environment-Society-Governance” Three-Dimensional Performance Analysis. West Forum. 2024, 34, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Can Green Investors Restrain Corporate Greenwashing? J. Fujian Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 240, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Ock, Y.-S.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Z. The Effect of Internal Control on Green Innovation: Corporate Environmental Investment as a Mediator. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, R.; Sias, R.W.; Starks, L.T. Voting with Their Feet: Institutional Ownership Changes around Forced CEO Turnover. J. Financ. Econ. 2003, 68, 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, S.; Han, Y.; Peng, K. The Nature of State-Owned Enterprises and Collection of Pollutant Discharge Fees: A Study Based on Chinese Industrial Enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Rajagopalan, U.; Alsmady, A.A. Environmental Accounting and Sustainability: A Meta-Synthesis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitorus, L.; Febrianto, S. The Dynamics of Implementing Sustainability Accounting Standards in Improving Financial Transparency and Accountability. GEOFORUM 2024, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, J.J.; Wild, J.M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Disclosure Transparency. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsaa, A.; Paulet, E. Firm Transparency and Employee-Oriented Corporate Social Performance. New Evidence from European Listed Firms. Manag. Int. 2022, 26, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R. The Impact of Corporate ESG Performance on Institutional Investors’ Shareholding Ratio. Int. J. Glob. Econ. Manag. 2024, 5, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Aziz, N.F.A.; Hashim, M.J.M. Influence of Corporate Information Transparency on Foreign Institutional Investors’ Shareholding Behavior: Evidence from Public Listed Companies in China. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2024, 16, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Huang, J. Can Transparency Governance Promote Interregional Coordinated Carbon Emission Reduction? A New Perspective from China Provincial Transparency Index. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 58, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiao, S.; Ge, C.; Sun, G. Corporate ESG Rating Divergence and Excess Stock Returns. Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, X.M.; Ly, K.C.; Mai, Y. The Relationship between Heterogeneous Institutional Investors’ Shareholdings and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 71, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xing, T. Does Environmental, Social and Governance Performance Lessen Analyst Optimistic Bias: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2023, 52, 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Cheng, X. Can ESG Indices Improve the Enterprises’ Stock Market Performance?—An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A.; Frost, T.; Cao, H. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure: A Literature Review. Br. Account. Rev. 2023, 55, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, J.; Ren, C. Unlocking ESG Performance Through Intelligent Manufacturing: The Roles of Transparency, Green Innovation, and Supply Chain Collaboration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhu, Q. ESG Performance and Green Innovation in a Digital Transformation Perspective. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2024, 83, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, H. Research on the Impact of Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors on Enterprise Innovation Investment—Based on the Perspective of Financing Constraints and Environmental Uncertainty. Ind. Econ. Rev. 2022, 16, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, Q.; Han, Y. Institutional Investors Drive Corporate Green Governance: Monitoring Effects and Internal Mechanisms. J. Manag. World 2024, 40, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Kong, D. Local Environmental Governance Pressure, Executive’s Working Experience and Enterprise Investment in Environmental Protection: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on China’s “Ambient Air Quality Standards 2012”. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 54, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Research on the Green Innovation Promoted by Green Credit Policies. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Lins, K.V.; Maffett, M. Transparency, Liquidity, and Valuation: International Evidence on When Transparency Matters Most. J. Account. Res. 2012, 50, 729–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, L. Does QFII Improve the Effectiveness of China′s Capital Market? J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2021, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R.; Svensson, J. Are Corruption and Taxation Really Harmful to Growth? Firm Level Evidence. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 83, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types | Name | Variable | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Corporate ESG Performance | ESG1 | Quarterly mean of the Huazheng ESG Score | - |

| ESG2 | Quarterly mean of Huazheng ESG Rating Scores assigned on a 1–9 scale | - | ||

| Core Explanatory Variable | Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor Shareholdings | QFII1 | Quarterly mean of QFII shareholdings | million shares |

| QFII2 | Quarterly mean of (QFII ownership ratio/Largest shareholder’s ownership ratio) | % | ||

| Mediating Variables | Green Technology Innovation | GTI | ln(number of green invention patent applications and green utility model patents + 1) | - |

| Green Investment | GI | Total green investment expenditure/Total assets | % | |

| Green Expenses | GE | Total environmental management costs | million RMB | |

| Moderating Variable | Information Transparency | TRANS | Constructed from the percentile means of five transparency-related variables | - |

| Control variables | Domestic institutional investor shareholdings | DII | Shareholding of Domestic Institutional Investors/Total Shares Outstanding | % |

| Return on Assets | ROA | Operating profit for the year/Total assets at the end of the year | % | |

| Ratio of Independent Directors | INDEP | Number of independent directors/Number of directors | % | |

| Fixed Assets Ratio | FAP | Net fixed assets/Total assets | % | |

| TobinQ | TobinQ | Market capitalization/(Total assets − Net intangible assets − Net goodwill) | - | |

| Financial Leverage | LEV | Total liabilities/Total assets | % | |

| Corporate Size | SIZE | Total assets | million RMB | |

| Cash Flow Ratio | CFR | Net cash flows from operating activities/Total assets |

| VarName | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG1 | 33,153 | 73.185 | 4.668 | 57.895 | 73.368 | 84.764 |

| QFII1 | 33,153 | 0.097 | 0.384 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2.708 |

| DII | 33,153 | 41.792 | 24.014 | 0.555 | 42.932 | 90.006 |

| ROA | 33,153 | 4.312 | 6.459 | −23.464 | 4.130 | 21.846 |

| INDEP | 33,153 | 37.617 | 5.347 | 33.330 | 36.360 | 57.140 |

| FAP | 33,153 | 21.920 | 15.441 | 0.196 | 18.726 | 68.387 |

| TobinQ | 33,153 | 2.179 | 1.385 | 0.873 | 1.737 | 9.330 |

| LEV | 33,153 | 41.931 | 20.378 | 5.048 | 41.189 | 90.788 |

| SIZE | 33,153 | 1310.522 | 3278.351 | 39.478 | 373.614 | 25,073.168 |

| CFR | 33,153 | 4.837 | 6.753 | −16.675 | 4.712 | 24.090 |

| GTI | 33,153 | 0.361 | 0.767 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 3.526 |

| GI | 33,153 | 8.324 | 10.891 | 0.000 | 4.281 | 57.564 |

| GF | 33,153 | 65.935 | 124.076 | 2.979 | 26.537 | 846.609 |

| TRANS | 33,153 | 0.303 | 0.193 | 0.005 | 0.285 | 1.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | OLS | Fixed-Effects | Fixed-Effects | Cluster (Firm) | |

| QFII1 | 1.482 *** | 0.658 *** | 0.270 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.251 *** |

| (22.390) | (10.391) | (4.187) | (4.016) | (2.765) | |

| DII | 0.007 *** | 0.004 | 0.004 | ||

| (7.057) | (1.630) | (1.033) | |||

| ROA | 0.192 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.113 *** | ||

| (43.330) | (27.002) | (19.439) | |||

| INDEP | 0.058 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.038 *** | ||

| (13.157) | (7.026) | (5.059) | |||

| FAP | −0.025 *** | −0.015 *** | −0.015 *** | ||

| (−15.336) | (−5.643) | (−3.769) | |||

| TobinQ | −0.443 *** | −0.143 *** | −0.143 *** | ||

| (−24.790) | (−7.026) | (−5.058) | |||

| LEV | −0.024 *** | −0.028 *** | −0.028 *** | ||

| (−17.708) | (−14.461) | (−9.239) | |||

| SIZE | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | ||

| (33.303) | (15.072) | (7.941) | |||

| CFR | 0.007 * | −0.012 *** | −0.012 *** | ||

| (1.763) | (−3.434) | (−2.891) | |||

| _cons | 73.042 *** | 71.924 *** | 73.149 *** | 72.607 *** | 72.607 *** |

| (2784.385) | (373.789) | (3894.260) | (287.519) | (198.987) | |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 33,153 | 33,153 | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,965 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.015 | 0.164 | 0.526 | 0.555 | 0.555 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change Dependent Variable ESG2 | Two-Period Lead ESG3 | Two-Period Lead ESG4 | Change Independent Variable ESG1 | Change Model ESG1 | Change Model ESG1 | |

| QFII1 | 0.049 ** | 0.238 ** | 0.048 ** | 0.245 *** | 0.245 *** | |

| (2.573) | (2.144) | (2.134) | (2.700) | (2.699) | ||

| QFII2 | 0.601 ** | |||||

| (2.514) | ||||||

| _cons | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effect | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effect | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| N | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,952 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.534 | 0.524 | 0.509 | 0.555 | 0.557 | 0.557 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| QFII_dum | ESG1 | |

| CSI300 | 0.315 *** | |

| (10.341) | ||

| imr | −3.428 *** | |

| (−2.607) | ||

| QFII1 | 0.269 ** | |

| (2.105) | ||

| _cons | Yes | Yes |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| N | 32,616 | 6017 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.716 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Stage QFII1 | Second Stage ESG1 | First Stage QFII1 | Second Stage ESG1 | |

| L.QFII1 | 0.503 *** | 0.503 *** | ||

| (26.518) | (26.507) | |||

| IV_QFII | 0.150 *** | 0.150 *** | ||

| (3.244) | (3.248) | |||

| IV2_QFII | 0.114 * | |||

| (1.806) | ||||

| QFII1 | 0.487 ** | 0.485 ** | ||

| (2.429) | (2.417) | |||

| Underidentification test (Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic) | 131.309 (Chi-sq(2) p-val = 0.0000) | 131.462 (Chi-sq(3) p-val = 0.0000) | ||

| Weak identification test (Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic) (Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic): | 3772.144 361.067 | 2515.429 246.345 | ||

| Hansen J statistic (overidentification test) | 0.010 (Chi-sq(1) p-val = 0.9193) | 1.251 (Chi-sq(2) p-val = 0.5350) | ||

| _cons | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 27,629 | 27,121 | 27,617 | 27,109 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.249 | −0.078 | 0.249 | −0.078 |

| Unmatched | Mean | %Reduct | t-test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Matched | Treated | Control | %bias | |bias| | t | p > |t| |

| DII | U | 44.66 | 40.97 | 15.20 | 11.64 | 0 | |

| M | 44.66 | 44.99 | −1.400 | 91.10 | −0.820 | 0.414 | |

| ROA | U | 5.367 | 4.010 | 21 | 15.97 | 0 | |

| M | 5.371 | 5.258 | 1.700 | 91.70 | 1.060 | 0.288 | |

| INDEP | U | 37.84 | 37.55 | 5.300 | 4.030 | 0 | |

| M | 37.84 | 37.90 | −1.200 | 78.20 | −0.670 | 0.500 | |

| FAP | U | 22.26 | 21.82 | 2.800 | 2.160 | 0.0310 | |

| M | 22.26 | 22.29 | −0.200 | 93.80 | −0.100 | 0.917 | |

| TobinQ | U | 2.213 | 2.169 | 3.200 | 2.410 | 0.0160 | |

| M | 2.213 | 2.218 | −0.400 | 87.90 | −0.230 | 0.820 | |

| LEV | U | 41.28 | 42.12 | −4.200 | −3.120 | 0.00200 | |

| M | 41.27 | 41.55 | −1.400 | 66.70 | −0.850 | 0.397 | |

| SIZE | U | 1539 | 1245 | 8.600 | 6.780 | 0 | |

| M | 1539 | 1643 | −3.100 | 64.50 | −1.630 | 0.102 | |

| CFR | U | 5.986 | 4.508 | 21.70 | 16.64 | 0 | |

| M | 5.989 | 5.949 | 0.600 | 97.30 | 0.340 | 0.733 | |

| (1) | |

|---|---|

| ESG1 | |

| QFII1 | 0.384 *** |

| (2.882) | |

| _cons | Yes |

| Controls | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes |

| ATT T-stat | 4.72 |

| N | 11,299 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.625 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESG1 | GTI | ESG1 | |

| QFII1 | 0.251 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.240 *** |

| (2.765) | (2.883) | (2.659) | |

| GTI | 0.249 *** | ||

| (4.475) | |||

| _cons | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,965 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.555 | 0.655 | 0.555 |

| Bootstrap 95% conf. interval | [0.0026017, 0.0206865] (Percentile CI) [0.003616, 0.0224028] (BC Percentile CI) | ||

| Mediated proportion of total effect | 4.313% | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESG1 | GI | ESG1 | |

| QFII1 | 0.251 *** | 0.451 ** | 0.246 *** |

| (2.765) | (2.306) | (2.714) | |

| GI | 0.011 *** | ||

| (3.191) | |||

| _cons | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,965 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.555 | 0.450 | 0.555 |

| Bootstrap 95% conf. interval | [0.0004392, 0.0105106] (Percentile CI) [0.0008383, 0.0111028] (BC Percentile CI) | ||

| Mediated proportion of total effect | 1.887% | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESG1 | GE | ESG1 | |

| QFII1 | 0.251 *** | 7.188 *** | 0.240 *** |

| (2.765) | (2.757) | (2.669) | |

| GE | 0.002 ** | ||

| (2.003) | |||

| _cons | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 32,965 | 32,965 | 32,965 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.555 | 0.918 | 0.555 |

| Bootstrap 95% conf. interval | [0.000274, 0.0279706] (Percentile CI) [0.0009159, 0.0296427] (BC Percentile CI) | ||

| Mediated proportion of total effect | 4.516% | ||

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| ESG1 | ESG1 | |

| QFII1 | 0.251 *** | 0.586 *** |

| (2.765) | (2.778) | |

| TRANS | 3.684 *** | |

| (15.895) | ||

| c.TRANS#c.QFII1 | −0.745 ** | |

| (−2.142) | ||

| _cons | Yes | Yes |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| N | 32,965 | 32,965 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.555 | 0.562 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, H.; Huang, X. Unlocking ESG Performance: How Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors Enhance Corporate Sustainability in China’s Capital Markets. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188303

Huang H, Huang X. Unlocking ESG Performance: How Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors Enhance Corporate Sustainability in China’s Capital Markets. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188303

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Hui, and Xiujuan Huang. 2025. "Unlocking ESG Performance: How Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors Enhance Corporate Sustainability in China’s Capital Markets" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188303

APA StyleHuang, H., & Huang, X. (2025). Unlocking ESG Performance: How Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors Enhance Corporate Sustainability in China’s Capital Markets. Sustainability, 17(18), 8303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188303