1. Introduction

It is a commonly held view among authors that financial development is a driving force behind economic development [

1,

2,

3]. A thorough examination of extant literature pertaining to the significance of financial inclusion in the context of sustainable development was undertaken [

4]. It was demonstrated that financial digitisation facilitates widespread access to financial services, thereby contributing to the promotion of sustainable economic growth. The authors of [

5] put forward the proposition that policymakers, governments, and technology providers should collaborate in the development of a digital economy, with a view to expanding the range of financial services available to small businesses. Digital lending platforms have the capacity to assist in the assessment of creditworthiness and thus facilitate the provision of microloans to small firms. Furthermore, ref. [

6] established a correlation between financial inclusion and sustainable employment, attributing this relationship to the efficacy of payments and the distinct impacts of credit.

Recent research also indicates that greater financial inclusion, facilitated by cooperation among policymakers, governments, and financial institutions, is associated with a reduced propensity to opt for informal services, thereby contributing to economic growth [

7]. Ref. [

8] presented the argument that enhancing financial education and the accessibility of financial intermediaries, in conjunction with the development of payment infrastructure across all rural demographic groups, contributes to financial inclusion. This, in turn, is posited to be a catalyst for economic development and income growth.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) identifies capital accumulation, savings, and the capacity for efficient financial transactions as pivotal factors in promoting sustainable economic development. The IMF emphasises that, in an economy characterised by the empowerment of women, the creation of employment opportunities, and the enhancement of production through financial inclusivity, these can serve as catalysts for the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially 1–4, 8, 10, and 13, among others [

9]. For instance, ref. [

10] examined the relationship between financial inclusion and the following Sustainable Development Goals: poverty reduction (SDG 1), hunger (SDG 2), health (SDG 3), economic growth (SDG 8), and industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9). The study found evidence that the expansion of bank branches in rural areas reduces poverty by increasing credit, which can convert smallholders into large-scale farming systems to improve agricultural production.

In addition, policymakers continue to regard financial inclusion as a primary strategic instrument for achieving inclusive growth and economic sustainability. This is due to the fact that the financial sector constitutes a pivotal component of any economy, and its development has the potential to generate significant benefits in terms of addressing socio-economic issues. In an efficient and transparent financial system, financial inclusion offers businesses and individuals high-quality financial products that respond positively to economic development issues [

11]. In addition, ref. [

12] contended that, employing ARDL and ECM-Granger causality techniques, an augmentation in the number of financial service providers and a proliferation of a competitive financial sector in Kenya would foster economic growth.

Ref. [

13] conducted a study with the objective of assessing the impact of financial inclusion on income inequality and poverty reduction in European countries. The findings of the study demonstrated that the expansion of financial inclusion significantly contributes to the reduction in poverty and income inequalities. The data indicated that an augmentation of financial inclusion by 1% results in a reduction in income inequality by 0.56%. The employment of the quantile regression method in a sample period extending from 2004 to 2019 indicates that financial development has a mitigating effect on inequalities in Central and Eastern European Union countries. This phenomenon is attributed to the enhancement of financial system stability and efficiency [

14].

This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that financial inclusion serves to reduce inequalities by increasing educational and entrepreneurial opportunities for those who are economically disadvantaged [

15]. The probit estimations with Gaussian copula terms, as found in data covering 113 countries, indicate a negative relationship between financial literacy and the likelihood of poverty reduction in different regions, as well as demographic and socioeconomic groups [

16]. Ref. [

17] is the result of an extensive review of 518 articles drawn from the Scopus database, spanning the period from 1970 to October 2024. The study concluded that improved access to financial products and services, underpinned by effective financial planning, is paramount to ensuring the well-being of the elderly population.

It can be hypothesised that a strong relationship exists between financial inclusion and the employment rate, on the grounds that greater financial inclusion has the capacity to reduce unemployment, due to enhanced access to financial services and products [

18]. Ref. [

19] conducted a study on highly unemployed economies in the European Union and confirmed that expanding the credit creation capacity has the potential to reduce unemployment. A strong positive relationship was found between digital financial inclusion and green innovation of firms. This relationship was determined using financial digitisation proxied by its degree and depth of use [

20].

Recent studies have observed a significant negative interdependence between financial development, financial instruments, and environmental degradation among European converging and developed countries. This is because increased financial development is associated with rising greenhouse gas emissions [

21]. This suggests that greater access to financial products may accelerate industrialization, which, in turn, can have adverse environmental impacts by causing pollution and generating a threat to long-term economic sustainability.

Recent studies have identified a number of research gaps in the field of financial inclusion, with examples including the following. For instance, ref. [

10] posited there is an absence of robust data connecting financial inclusion to non-financial Sustainable Development Goals. Conversely, ref. [

19] argued that understanding the conditions under development in the financial sector of EU member countries could help lower the rate of unemployment. Despite the fact that a number of the preceding studies have examined the relationship between financial inclusion and economic growth and development, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, none of them have analysed the influence of the Coronavirus pandemic on these relations, particularly in EU countries. The following discussion will firstly provide a basis for formulating the aim of this study and the research hypothesis.

The objective of this study is to examine the hypothesis that financial inclusion had a positive impact on the economic development of selected European economies between 2014 and 2023, especially during the period beyond the COVID pandemic. The relationship between these phenomena is examined by means of proprietary indicators that characterise selected areas. The restriction of the present discussion to European Union countries, which are a relatively homogeneous group in terms of economic development, will facilitate a reliable analysis of the occurrence of the aforementioned relationship. This assumption is founded upon the existence of evidence that suggests that alterations in economic performance within European countries are highly analogous, while the heterogeneity of their macroeconomic indicators is waning, a consequence of nominal, real, and institutional convergence. In both 2009 and 2020, the aforementioned countries demonstrated comparable responses to the global economic crisis and the economic downturn precipitated by the emergence of the novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [

22].

In the context of financial inclusion, a range of factors were taken into consideration. These included the level of infrastructure, the number of transactions, and the number of participants in the banking system. The latter was measured by the number of deposit and credit accounts. Conversely, the estimation of economic development was derived from the budget deficit/surplus, the price change index, the level of public debt, and a metric widely regarded as a direct indicator of economic development: namely, gross domestic product per capita. The present study introduces an original composition of financial inclusion and sustainable economic development characteristics, thus adding to the extant literature on the subject.

The significance of these considerations arises from the fact that the extant empirical research results remain inconclusive, and several questions remain unanswered. For instance, it is important to consider whether financial inclusion can contribute to sustainable economic development in the European Union Member States. This is particularly relevant in the context of the transition to digital economies, where traditional measures such as ATMs, debit/credit cards, deposit accounts in commercial banks, and loan accounts may no longer fully reflect the extent of financial inclusion.

The attainment of the research objective was predicated not solely on the utilisation of original synthetic measures, but chiefly on the implementation of econometric models that delineated the relationships between them.

The subsequent section undertakes an exploration of the extant literature to offer a more profound insight into the definition of financial conclusion and the meaning of public fiscal measures in terms of long-term economic sustainability. The third section of the text is of a methodological nature, with the presentation of the data, the construction of financial inclusion and economic development indices, and models. The purpose of these is to examine the role of financial inclusion in the context of sustainable economic development. The fourth section of this study presents the results and a discussion of the findings. The final section, the fifth, offers discussion, conclusions, policy recommendations, and suggestions for further research.

2. Literature Review—Discussion on Definitions of Financial Inclusion and Economic Development

It is evident that both financial inclusion and economic development are inherently complex phenomena due to their multidimensional nature. Consequently, both of these concepts are challenging to measure directly. Consequently, in the context of both phenomena, it becomes imperative to devise aggregate measures based on partial measures that delineate specific aspects of these two concepts. This finding indicates that the precision of the analyses conducted and the reliability of the outcomes depend significantly on the accurate delineation of these terms. The conclusions drawn by researchers are contingent on the research methods employed, the sources of statistical data and their quality, the period under study, the cross-sectional scope of the research, and the occurrence and influence of outliers [

23].

From the mid-1990s until the publication of more recent studies, researchers and policymakers sought to define financial inclusion based on economic and financial theories, while also exploring empirical findings. The relationship between financial inclusion and socio-economic issues was thoroughly explored, leading to the development of comprehensive strategies with the potential to enhance the well-being of societies in a sustainable manner. For instance, refs. [

24,

25] posited that financial inclusion occurs when no individual is marginalised within a formal financial system, financial services are available and easily accessible and can be utilised with ease. Consequently, three dimensions of financial integration were identified: accessibility, affordability, and usability.

According to [

26], financial inclusion can be defined as a mechanism through which individuals are able to save and access credit at reasonable rates in a regulated financial system, thereby contributing to economic growth. It is evident that the realization of financial inclusion is contingent upon the enhancement of infrastructure, such as the expansion of internet coverage in rural regions. This is imperative to facilitate the effective utilisation of technology in accessing financial services. According to [

27], financial inclusion can be defined as the practice of ensuring prompt, reasonably priced, and suitable accessibility to an eclectic assortment of financial products, with a focus on vulnerable groups.

It is argued that such accessibility is predominantly accomplished through the implementation of financial literacy programmes, as well as infrastructure and institutional innovations [

28]. The concept of financial inclusion is predicated on the premise that financial service providers endeavour to rectify market and non-market barriers to accessing financial services, thereby reducing the cost and risks associated with offering such services. According to the OECD (2013), the term “financial inclusion” refers to the situation where all segments of society can access financial products in a timely, adequate, and affordable manner, through the implementation of innovative approaches to promote economic and social inclusion.

This paper contributes to the extant literature on financial inclusion by proposing a definition of reliable systems that enable unbanked individuals and firms to deposit money, make payments, and access affordable credit. The purpose of these systems is to transform the lives and activities of those who are sustainably marginalised by the financial system. The implementation of such a system, bolstered by effective public expenditure, signifies the elimination of impediments in the banking sector, fostering robust and dependable capital markets that facilitate firms in acquiring capital to augment employment prospects. Additionally, it is anticipated to result in an escalation in individuals’ disposable incomes, empowering them to contribute towards insurance premiums, thereby mitigating existing risks.

In the context of analysing the diverse trajectories of growth and development across individual nations, it is imperative to acknowledge the absence of a universally applicable formula (concept) for long-term growth and economic development [

29]. This assertion is predicated on the recognition that a multitude of economic theories pertaining to growth and development exist, and that individual countries exhibit marked differences in economic and social dimensions. The concept of economic development is challenging to define with clarity and consensus among researchers, due to its qualitative nature and multidimensional character, akin to that observed in the context of financial inclusion. It is also noted by many authors that international comparisons of economic growth and development can be difficult when countries are at different stages of the business cycle [

30] and when specific estimation methods are used, which often result in important information contained in the original statistical data being overlooked [

31].

One of the most significant factors determining the level of economic development, understood as a series of positive changes, is economic growth. Economic development is regarded as a sequence of alterations, encompassing both quantitative and qualitative-structural dimensions, that are both directed and irreversible, occurring within the framework of intricate economic systems. Economic growth, its inherent character, and its velocity are regarded as catalysts for these transformations [

32]. For comparison, ref. [

33] defines economic development as a process resulting in systematic growth in labour productivity. By contrast, ref. [

34] contends that economic development can be said to occur when the transition of the economy to a new point of equilibrium reduces the losses associated with maintaining the stability of the economic system.

A comprehensive examination of the conceptualization of development and its various manifestations, along with the associated theoretical frameworks, can be found in the works of [

35,

36]. The characteristics of the phenomena of development and sustainable development were also presented by [

37]. The identification of the key factors of economic development is of decisive importance in the construction of economic policy aimed at ensuring sustainable growth and development, especially during economic crises. Recent studies demonstrate that the process of generating domestic products in EU countries was dominated by classic growth factors such as consumption, investment, export, and labour productivity [

38].

The global crisis that commenced in 2007 has had a significant impact on the macroeconomic situation and the dynamics of economic growth. The level of public debt has been identified as a key factor in this regard [

39,

40]. Excessive public debt has been demonstrated to result in budget revenues being allocated to servicing this debt, rather than being utilised to finance expenditures related to increasing the competitiveness and innovation of the economy, and to meeting the needs of the population. In order to avoid the inflationary impact of public debt, countries must take prompt measures to validate public debt and its proportional growth to GDP [

41]. A number of researchers have concentrated on the relationship between fiscal policy, public debt, public expenditure, and economic growth and development, yielding equivocal results.

For instance, as demonstrated by [

42], government investment has been identified as a significant tool for economic sustainability against consumption. This is in order to restore a shrinking economy and reduce the public debt-to-GDP ratio. The persistent disparity between government expenditure and sustainable development, characterised by the accumulation of public debt, is anticipated to persist until the year 2030. The question, therefore, arises as to whether such a gap can be overcome. The answer is that this can only be achieved if government programmes are redesigned and adopt micro-policies that impact household socioeconomic transformation and support GDP growth [

43]. Ref. [

44] arrived at the finding that there is a significant negative correlation between public debt and economic growth in the short-term and long-term, with no such effect in the medium period.

Concurrent findings were reported by [

45]. The present authors demonstrated that public debt exerts a detrimental effect on the economy, thus indicating that the public debt-to-GDP threshold has increased considerably to 72.0% in EU countries by 2022, thus exceeding the 60% target of the European Union Stability and Growth Pact. In 2023, the average level of the indicator “the government debt-to-GDP ratio” increased to 81.0%. According to Eurostat (2024), with the exception of Portugal and Cyprus (+0.7%, +4.3%), all other Member States recorded budget deficits in 2024. The highest deficits were recorded by Poland and France at −6.6% and −5.8%, respectively. Nevertheless, it is imperative to underscore the assertion that the repercussions of elevated debt levels on the present and future economic conditions of individual economies are contingent upon their respective levels of development. In this regard, ref. [

46] formulated some interesting conclusions. The authors posit that, in low-developed OECD countries, public debt has a negative impact on economic growth when the debt-to-GDP ratio is below 43.51%, and a positive impact when it is above 58.14%.

In the present study, economic development is approximated by variables that are significant in the short term, including price dynamics and the balance of government revenues and expenditures. By contrast, its sustainable nature is emphasised by long-term macroeconomic parameters such as public debt and GDP per capita.

3. Materials and Methods

- –

X1 (Number of ATMs per 100,000 adults),

- –

X2 (Number of debit cards per 1000 adults),

- –

X3 (Number of mobile and internet banking transactions per 1000 adults),

- –

X4 (Number of loan accounts in commercial banks per 1000 adults),

- –

X5 (Number of deposit accounts in commercial banks per 1000 adults).

The second set of variables is employed to characterise the dimensions of economic development:

- –

Y1 (Government net lending/net borrowing as % of GDP),

- –

Y2 (Inflation rate),

- –

Y3 (Public debt as % of GDP),

- –

Y4 (GDP per capita, constant 2015 USD $).

In the process of calculating the values of the analysed indicators, the variables inflation rate (Y2) and relative public debt (Y3) were changed from destimulants to stimulants. The study was limited by a paucity of information concerning two variables: the number of mobile and internet banking transactions per 1000 adults, and the number of loan accounts in commercial banks per 1000 adults. Consequently, only nine European Union countries were included in the study: Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary, Latvia, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Spain.

It is important to note that a number of additional variables have been utilised in preceding studies to substantiate the concept of financial inclusion. Ref. [

47] considered the number of bank accounts, the value of bank deposits, the number of bank branches, and the value of credits granted to the private sector. In their study, ref. [

15] advanced a multifaceted framework for assessing financial inclusion, encompassing a range of variables. These included the value of formal and informal loans, the aggregate debt from banking institutions, and the annual interest rates applicable to both formal and informal loans. Ref. [

48] sought to operationalise the concept of financial inclusion by measuring it using a range of variables. These included awareness of, access to, and usage of the financial inclusion scheme, as well as financial literacy. Ref. [

49] employed only net financial flows as a metric, while [

50] examined the volume of remittances and the number of individuals who utilised mobile phones to settle bills online within the preceding 12 months.

The research by [

51] was based on more traditional indicators, such as the number of commercial bank branches and ATMs, the value of private sector credit and pension and mutual fund assets, and the value of life and non-life insurance premiums. In contrast, ref. [

13] proposed the construction of a financial inclusion index, with the number of commercial banks, credit unions, ATMs, and outstanding deposits and loans with commercial banks being used to this end. The majority of the variables were expressed in a relative manner, either as population-based or as a percentage of GDP.

3.1. Data Breaks and Descriptive Statistics

The data for selected countries (Cyprus, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain) and three variables (X3, X4, and X5) were subject to seven data breaks. The completion of the aforementioned models was achieved by means of extrapolation, with linear and non-linear trend models being utilised in the process.

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the basic descriptive statistics of the variables characterising the level of financial inclusion and the level of economic development, respectively.

Ref. [

52] established that the presence of ATMs and an increasing number of debit card holders had a significant impact on economic sustainability. However, an analysis of contemporary trends in the number of ATMs in relatively developed countries such as the Netherlands, Spain, Cyprus, and Malta reveal that this conclusion is no longer valid. During the period under scrutiny, the highest number of ATMs per 100,000 adults was observed in Portugal, while the lowest was in Cyprus. Evidence of this phenomenon can be observed in the data concerning the number of debit cards per 1000 adults. The highest number of mobile and internet banking transactions per 1000 adults was observed in the Netherlands, with Spain recording the lowest number.

According to the explanation provided by the IMF, this indicator in Spain is considerably lower than in other countries that have been examined. This is due to the fact that Spain does not report all mobile and internet banking transactions, but only the available information regarding transactions from credit and debit cards. This exclusion includes transactions such as deposits, bill payments, and account transfers. The data set included the number of loan accounts in commercial banks per 1000 adults. Spain was the leader, while Latvia was the worst-performing country. The number of deposit accounts in commercial banks per 1000 adults was highest in Malta and lowest in Spain.

In the period spanning from 2014 to 2023, the mean value of the relative government net borrowing was highest for Spain and lowest for the Netherlands. According to the mean level of relative public debt, the most unfavourable situation was observed for Portugal, and the most favourable for Bulgaria. The mean rate of increase in prices of goods and services was highest in Hungary and lowest in Cyprus. In 2023, the Netherlands was identified as the most developed country according to GDP per capita, while Bulgaria was found to be the least developed country in this regard.

3.2. Financial Inclusion (FI) and Economic Development (ED) Indexes

The financial inclusion index was derived from a data set comprising five variables (X

1–X

5), which collectively probed three dimensions of financial infrastructure and services: availability, penetration, and usage. The economic development index was calculated based on four macroeconomic parameters (Y

1–Y

4). The process of normalisation of the individual variables was conducted within the range of 0–1 by means of the method of zero unitarization, in accordance with the established formula [

53]:

where:

—the normalised value of the variable ,

—the real value of the variable,

—the minimum and maximum value of the variable respectively.

Therefore, the financial inclusion (FI) index for period

t is calculated as a sum of values of normalised variables

:

where:

zit—the normalised value of the original value xit for period t,

i—a number of the variable representing the financial inclusion dimension, i = 1, 2, …, n.

The economic development (ED) index is determined using a similar formula:

where:

zkt—the normalised value of the original value xkt for period t,

k—a number of the variable representing the economic development dimension, k = 1, 2, …, m.

In order to verify the robustness of the values of the aggregate financial inclusion indices based on Formula (2), it was necessary to recalculate them using additional methods. The initial method was Taxonomic Measure of Development, the most well-known pattern method of linear ordering developed by the Polish school of taxonomy [

54]. In order to complete the robustness check, an alternative variant of the calculation of aggregate financial inclusion indices was utilised. This variant was based on the formula of aggregation (2), but an additional individual indicator was incorporated, namely “Number of commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults”. In both above cases under consideration, the correlation coefficient between the original values of the aggregate indexes of financial inclusion and the new values ranged from 0.906 to 0.999, with only a few exceptions.

3.3. Determining the Regression Model

In order to examine the long-term relationship between financial inclusion and economic development in a specific country, an econometric model based on time series data was utilised:

where:

α—an intercept,

β—the slope,

, —economic development and financial inclusion indices for country j and year t, respectively,

εi —an error term.

In the aforementioned model, it was hypothesised that financial inclusion would serve as a mitigating factor against the deleterious consequences of excessive public debt and budget deficits, as well as economic growth and high inflation rates. The Ordinary Least Squares method was employed to estimate the regression model coefficients [

55,

56].

4. Results

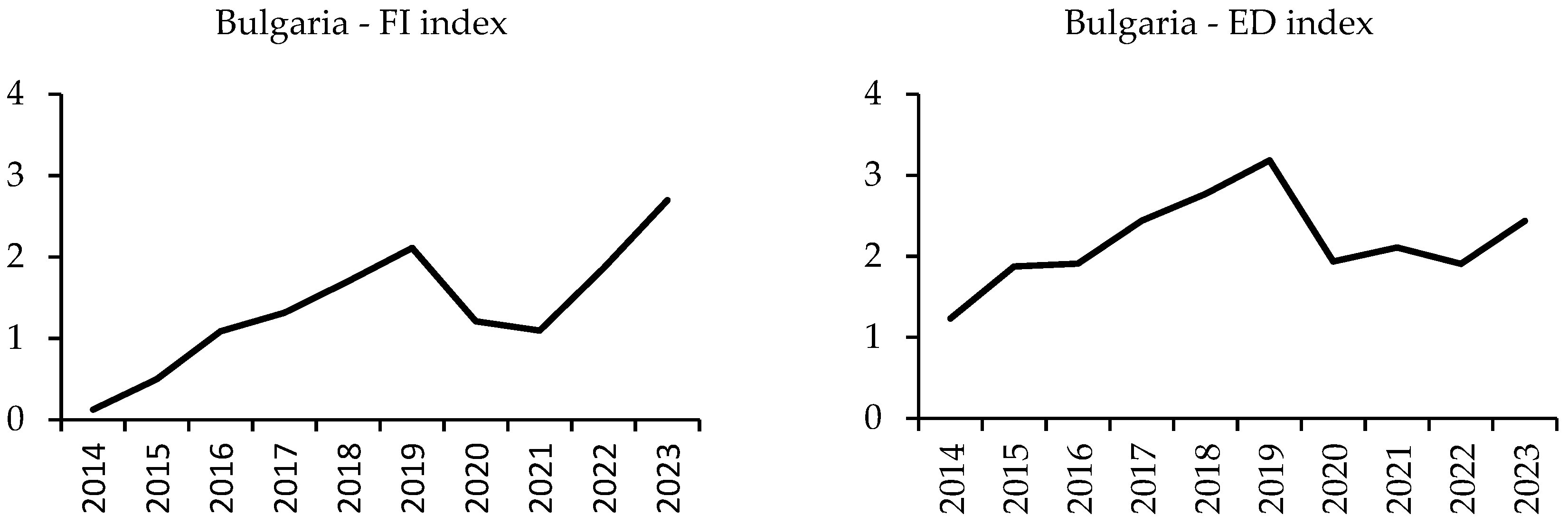

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the development of the two indices under consideration, financial inclusion (FI) and economic development (ED), is demonstrated throughout the period under study.

With respect to economic development, all countries experienced a decline in 2020. This phenomenon can be attributed to the global economic crisis triggered by the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic. The decline indicates that the indicator describing the level of economic development has been constructed correctly. In the subsequent three-year period, certain countries demonstrated a rapid recovery, achieving levels of economic activity that approximated those experienced prior to the crisis. The aforementioned countries include Cyprus, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. It is evident that other countries, most notably Bulgaria, Hungary, and Malta, experienced considerable difficulties in their economic recovery.

The level of financial inclusion exhibited a greater degree of variation. An analysis of the data reveals that Hungary, Poland, Portugal, and Spain demonstrated the most favourable outcomes in this area. In the case of the latter country, the level of financial inclusion would be significantly higher if the variable describing the number of mobile and internet banking transactions per 1000 adults were calculated in the same way as for the other countries. Conversely, Cyprus, Latvia, and Malta have witnessed a consistent decrease in the value of the financial inclusion index during the period under scrutiny. It is important to note that variables with a low degree of volatility were excluded from the calculation of financial inclusion indices for certain countries. The aforementioned findings pertain to variable X1, as they apply to six countries, and variable X5, as they apply to two countries.

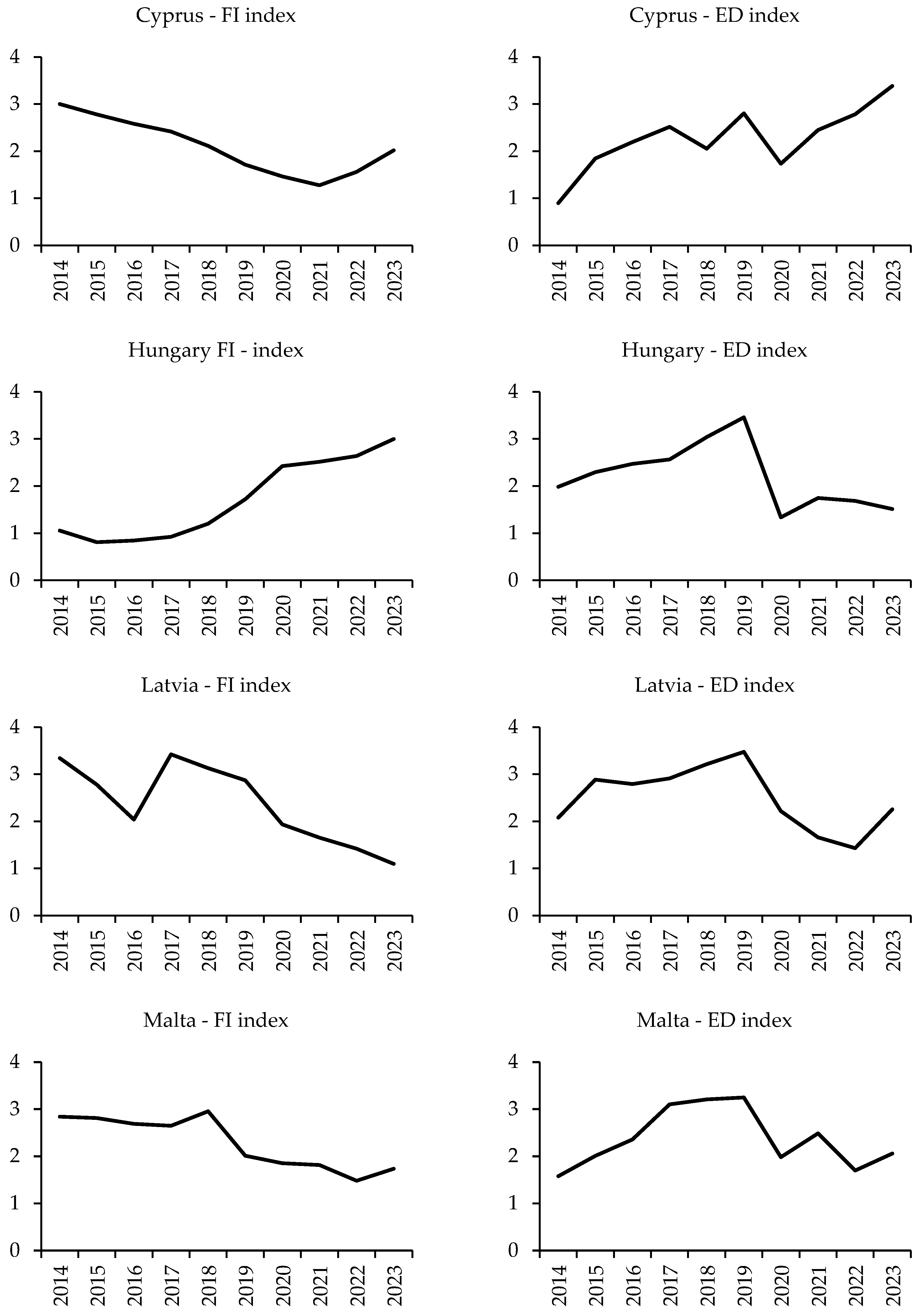

Figure 2 presents the correlation plots of the financial inclusion (FI) and economic development (ED) indicators for the period 2014–2023.

Evidently, a discernible dichotomy exists between two distinct sub-periods, characterised by divergent relationships between the indices under consideration. In the period between 2014 and 2019, the anticipated positive correlation between the degree of financial inclusion and the level of economic development was evident, with a few notable exceptions (Cyprus, the Netherlands, and Malta). Nonetheless, the final years of the period under study witnessed an interruption to this regularity. This phenomenon can be attributed to the adverse repercussions of the Coronavirus pandemic. The evolution of this relationship is particularly unusual in the case of Malta. A negative correlation was initially observed, followed by a subsequent positive correlation in the latter years.

As illustrated in

Table 3, the estimation results for models that describe the relationship between financial inclusion and the level of economic development are presented. In the estimation of the parameters of these models, any anomalous observations that would distort the regularities were disregarded. The majority of these were observations from the post-pandemic period. In only a few cases were these observations considered outliers, and their removal resulted in a substantial enhancement of the models’ goodness of fit.

It was evident that all models demonstrated a high degree of goodness of fit, with all parameters proving to be statistically significant. The Malta model (A), constructed using data from the early years of the period under study, was an exception. The correlation between financial inclusion and economic development is positive for the majority of countries, with the parameter characterising the strength of this relationship generally oscillating around a value of 1. However, in the case of three countries: Cyprus, Malta (B), and the Netherlands, a negative correlation between financial inclusion and economic development was indicated. This is incongruent with economic theory and expectations. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that the findings may not be entirely representative, primarily due to the limited sample incorporated into the study.

In order to ascertain the robustness of the received results in the context of endogeneity bias, it was necessary to test all models using the procedure proposed by [

57]. This procedure was based on the reduced form of the models and control (exogenous) variables. The applied control variables were population density and Internet users as percentage of individuals. In all cases, with the exception of one for Bulgaria and internet users used as control variable, the findings demonstrated an absence of endogeneity bias.

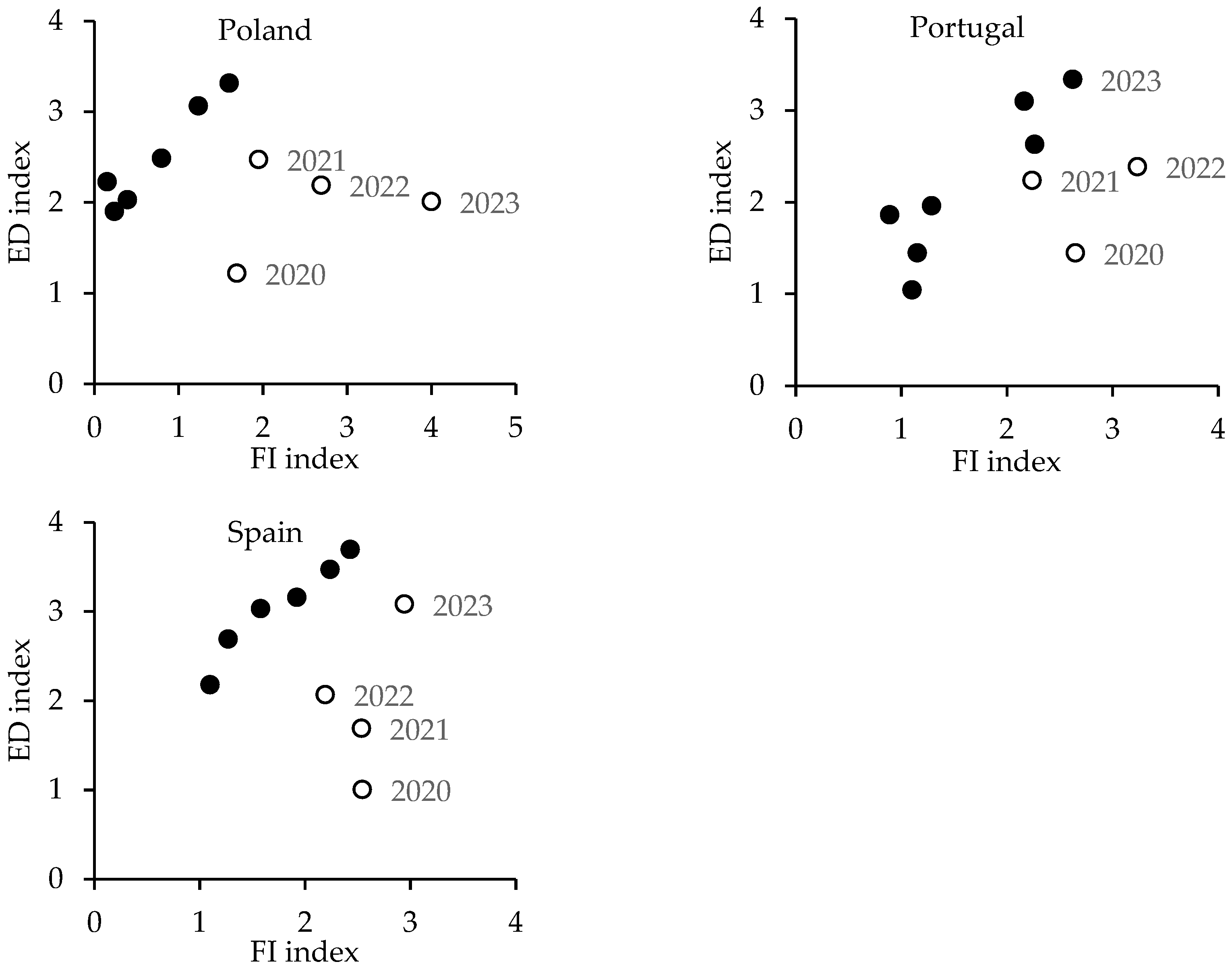

The data set, encompassing all countries and years, was utilised to ascertain the existence of a long-term, sustainable relationship between the degree of financial inclusion and the level of economic development. In order to facilitate the comparison of the variables, they were normalised using formula (1), with the minimum and maximum values that were recorded for all objects over the entire study period being taken into consideration. In contradistinction to preceding approaches to normalisation, this methodology facilitates the comparison of values calculated for disparate countries over time. The data presented herein is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The shape of the scatterplot of the indices, which were calculated based on normalised complete data, clearly demonstrates that positive and negative correlations between the examined indices for individual countries are not accidental. A common pattern has not been identified among the Member States of the European Union in this respect. The Pearson linear correlation coefficient was found to be −0.05, thereby confirming the absence of cross-temporal dependence.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Despite the extensive awareness of the beneficial impact of financial inclusion on economic growth and development, there are still many limitations in this area. Households are likely to be financially excluded due to unemployment and low-income levels [

51,

58] and low usability of bank accounts. It is possible that policymakers may utilise the findings in order to facilitate the restructuring of policies and to guide the government in its expenditure models, with a view to engendering opportunities for financial inclusion.

They should prioritise targeted financial inclusion strategies that go beyond traditional metrics such as the number of ATMs, as these no longer reflect meaningful access in highly developed, digitised economies. To better capture financial behaviour, governments should invest in real-time usability indicators such as active digital banking engagement, transaction frequency, and quality and costs of financial services. EU-level policy must be more focused on harmonising indicators of financial inclusion to ensure their comparability across member states. They should also revise public expenditure models to include technology infrastructure grants for underserved areas. This would enable FinTech expansion that aligns with the SDGs.

Moreover, it is important to note that insurance companies and financial institutions may also utilise the findings to address any existing gaps that impede efficient access to financial services. This, in turn, will contribute to sustainable economic development. Financial institutions should be encouraged to develop affordable, trustworthy digital tools to help them reach populations who are reluctant to abandon cash. The incorporation of digital financial instruments, such as FinTech, has the potential to enhance financial inclusion. The utilisation of such tools has the potential to promote the financial inclusion of individuals and businesses in low-income regions, thereby enabling them to access capital and engage in sustainable economic activities. This, in turn, encourages them to manage their finances by making effective investment decisions. As demonstrated in [

59], the development of technological infrastructure facilitates the support of SDGs by FinTech. This is due to the substantial enhancement of financial inclusion in urban areas that is enabled by FinTech, which results in a significant reduction in poverty and the fostering of effective collaboration between financial service providers and customers.

However, it is important to acknowledge that despite advancements in institutional development and improvements to the financial system’s infrastructure, certain demographic groups continue to face financial exclusion due to their reluctance to adopt digital or fintech tools for their daily transactions, primarily due to concerns regarding trust and a reluctance to relinquish their reliance on cash [

4].

A salient conclusion of the study is that, in countries with a high level of financial development and digitisation, certain components of the measures employed to assess financial inclusion are not only outdated but, more importantly, inadequate. A thorough examination of the available data set, which encompasses the developmental stage of financial services within the European Union countries under scrutiny, unequivocally substantiates the exclusion of the number of ATMs.

The findings of the study did not support the hypothesis that a positive relationship exists between financial inclusion and economic development within the whole examined sample. In certain countries, an evident negative correlation between these phenomena has been observed, particularly in the aftermath of the pandemic. A clear distinction can be observed between two distinct sub-periods, characterised by divergent relationships between financial inclusion and economic development. It was observed that, prior to 2019, a positive relationship was evident, given that during the initial years under review, there was no economic slowdown. The nature of the relationship has undergone a shift during the latter part of the period under consideration, a development that can be attributed to the adverse impact of the Coronavirus pandemic.

The main reason for identifying such a negative relationship in the case of Cyprus, Malta, and the Netherlands is the decrease in the value of the FI index during the review period. This decline is due to the consideration of two indices: the number of ATMs per 100,000 adults and the number of loan accounts in commercial banks per 1000 adults. As mentioned above, these variables may not significantly impact the functioning of the financial system or transactions in countries with highly digitised financial services and products.

A considerable number of studies have also yielded equivocal or contradictory findings regarding the correlation between financial inclusion and macroeconomic indicators. Ref. [

60] examined sub-Saharan Africa, determining that the impact of financial inclusion on per capita household consumption expenditures is contingent upon the ratio of received remittances to GDP. It was observed that there is a threshold level below which a positive influence is evident. Consistent findings were reported by [

61], who demonstrated that financial development exerts a positive influence on per capita household consumption expenditures, albeit exclusively in middle- and high-income countries.

Ref. [

62] analysed digital financial inclusion in China across three dimensions (breadth of coverage, depth of usage, and level of digitalisation) and 32 specific indicators. They found a higher level of digital financial inclusion to be associated with lower income inequality within provinces, but not across provinces. It was also observed that digital financial inclusion exerts a more significant impact on the incomes of less educated, rural, and female-headed households. Conversely, other researchers have reached contradictory conclusions. For instance, a study by [

63] found that the expansion of financial inclusion through fintech channels leads to a reduction in income inequality. However, ref. [

64] demonstrated that financialisation and digitisation have the potential to exacerbate income inequality, as high-income households tend to have greater access to low-cost financial products and digital technologies. It has been demonstrated by certain studies that economic development is a catalyst for the relationship between financial inclusion and income inequality [

65], while others have indicated the pivotal role of initial financial depth [

66].

As demonstrated by [

67], the impact of financial inclusion on the performance and concentration of the insurance market is conditional on its prevailing structure, as evidenced by an analysis of data from Central, Eastern, and South-eastern European countries. In the study conducted by [

68], the relationship between financial development and economic growth in 13 Central and Eastern European developing countries during the period of 2001–2020 was examined. The study demonstrated that the development of the banking sector, as measured by credit variables, had a negative influence on economic growth. Conversely, the findings of ref. [

69] suggested a positive correlation between bank credit levels and stock market capitalisation, as well as economic growth in EU countries.

However, upon interpretation of the received results, it is important to acknowledge that due to the gaps in statistical data, the study encompassed only nine European Union countries. Consequently, conclusions were derived exclusively through the utilisation of econometric models utilising data in the form of relatively short time series. It is imperative to acknowledge that the conclusions and recommendations derived from the aforementioned limitations may not be indicative of the European Union as a whole.

It is recommended that future research on the importance of financial inclusion for economic growth and sustainable development consider the impact of an individual country’s level of socio-economic development and cultural aspects in greater detail. A potential avenue for future research would be to extend the analysis to include the sensitivity of the results obtained to different constructions of indicators characterising the level of financial inclusion and economic development. In addition, the use of different data analysis tools, including multidimensional analysis methods, could be investigated.