1. Introduction

Aligning students’ initial expectations with their subsequent perceptions of the services, products, and systems delivered by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) is widely recognized as a pivotal gauge of perceived quality [

1]. Because accrediting bodies explicitly evaluate this perceived quality when auditing universities, initiatives that enhance the Student eXperience (SX) yield benefits for both learners and institutions. By embedding sustainability principles into SX-focused strategies, institutions strengthen their social responsibility agendas and amplify the long-term impact of improvements. SX’s rigorous diagnostics help administrators identify gaps, strategically allocate resources, and increase student satisfaction, improving an institution’s competitive position. Although several established instruments are already used to appraise service quality in higher education [

2], they tend to be generic, confined to specific interaction domains, and require substantial adaptation to meet the diverse needs of different and diverse student populations.

HEIs increasingly compete in a borderless marketplace where academic quality is judged not only by learning outcomes but also by the totality of impressions students accumulate before, during, and after enrolment. The SX concept frames those impressions as a field-specific instantiation of Customer Experience (CX). Students act as consumers who evaluate a bundle of institutional “touchpoints” that range from admission portals and virtual learning environments to classroom interactions, extra-curricular services, and social interactions [

3]. Within CX theory, experience arises from the continuous interplay of cognitive assessments, affective reactions, and behavioral intentions. Translating this logic to the university context clarifies why measuring SX is strategically critical. Comprehensive SX diagnostics empower administrators to identify “pain points”, allocate resources where they matter most, and ultimately enhance perceived educational quality, an attribute weighted heavily by accreditation agencies, ranking bodies, and prospective students [

4]. Moreover, by illuminating how institutional encounters are interpreted across cultures, SX evaluation facilitates international cohorts’ social and academic integration, a priority for HEIs committed to diversity and global engagement.

Despite its managerial importance, SX research remains fragmented. Many instruments inherit item pools from generic service-quality scales, focus on isolated interactions such as learning-management systems, or disregard the cultural heterogeneity that shapes expectations and satisfaction [

5]. A recent systematic review converges on three broad SX dimensions—Educational, Social, and Personal—yet empirical studies seldom test how these spheres interact with students’ cultural value orientations.

To address this gap, the present study develops and validates a culturally responsive SX scale grounded simultaneously in SX/CX theory and Hofstede’s six-dimensional national-culture model [

6]. Beginning with a concept-mapping exercise, we generated thirty-one candidate items: nine Educational (ED), seven Social (SO), two Personal (PE), and twelve cultural statements. One item, an open-ended prompt, is retained for qualitative richness but excluded from the quantitative analyses reported here.

A total of 302 valid responses were collected from 321 undergraduates spanning seventeen nationalities across Latin-American and Spanish universities, providing ample heterogeneity for cross-cultural testing. Given the ordinal data, we used a diagonally weighted least-squares estimator within an SEM framework [

7,

8]. Confirmatory factor analysis validated the three-factor SX model and six cultural factors, and a hierarchical SEM showed that the second-order Cultural Aspects construct positively predicts overall SX.

The validated scale exhibits a strong factorial validity and composite reliability, offering researchers a concise yet comprehensive diagnostic capable of internationally benchmarking SX. For practitioners, the instrument functions as an actionable dashboard: item-level scores reveal granular experience gaps; dimension-level scores inform strategic initiatives; and culture-linked diagnostics guide the design of equity-oriented interventions that resonate with domestic and international students. By embedding cultural nuance at the conceptual core rather than treating it as an ex-post segmentation variable, this study advances SX scholarship and provides HEIs with a rigorous tool for enhancing perceived quality, overall satisfaction, and the successful integration of a diversifying student body.

In response to the fragmented nature of existing instruments, this study also introduces the concept of SX diagnostics as a strategic tool to identify experience-related gaps across educational, social, and personal dimensions. While the term is used conceptually to frame the practical utility of the scale, the empirical validation presented here offers a foundational step toward operationalizing these diagnostics in institutional contexts. The structural model results highlight the predictive power of cultural orientations over student experience, further supporting the use of the scale as a research instrument and a diagnostic resource for policy and service design in intercultural settings.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Service Science

Service Science has emerged as an inherently interdisciplinary domain that synthesizes insights from organizational theory, human-centered design, business strategy, and information technology to illuminate the structure and behavior of contemporary service systems. Maglio and Spohrer conceptualize these systems as “dynamic value co-creation configurations of resources/people, technology, organizations, and shared information” [

9], underscoring their socio-technical character and capacity to adapt over time through continuous feedback loops among stakeholders. By viewing value not as a static output but as a co-generated outcome of interactions, Service Science offers a holistic analytical lens particularly salient for HEIs, which increasingly operate as complex service ecosystems in which students, faculty, administrators, and digital infrastructures jointly craft educational value. Subsequent theoretical refinements extend this perspective by situating service systems within broader networks of interdependent actors and emphasizing information flows’ pivotal role in coordinating resource integration and fostering innovation [

10]. CX is a cornerstone construct within this framework that bridges micro-level perceptions with macro-level system performance. Schmitt’s experiential marketing paradigm, which advocates replacing product-centered logics with orchestrated experiential encounters capable of “awakening the senses and reaching the heart of the consumer” [

11], operationalizes CX through five strategic experiential modules: sense, feel, think, act, and relate. These modules collectively offer a solid theoretical scaffold for designing measurement instruments by mapping how educational service systems evoke sensory, emotional, intellectual, behavioral, and social responses in students and how these responses, in turn, inform value co-creation processes within culturally diverse academic environments.

Although our scale was not explicitly structured on Schmitt’s experiential marketing paradigm, clear conceptual parallels can be observed. Service science frames higher education as a value co-creation process, and Schmitt’s Strategic Experiential Modules illuminate how different aspects of experience manifest in this context. For example, elements of THINK/ACT resonate with the ED items that capture cognitive challenge and application of learning; RELATE aligns with the SO items reflecting collaboration and faculty–student interaction; and FEEL/SENSE correspond to the PE items linked to well-being and motivation. Thus, while the instrument was developed independently, its three dimensions are consistent with service-science perspectives.

2.2. Customer Experience (CX)

Laming and Mason conceptualize CX as the totality of physical stimuli and affective states that arise during a consumer’s interactions with a brand’s product or service, beginning with the first conscious encounter and extending seamlessly through the entire consumption journey into the post-purchase phase [

12]. Building on this processual view, Joshi characterizes CX as the cumulative set of episodes a customer accrues throughout the duration of the service relationship, thereby framing experience as an evolving ledger of brand-related engagements rather than a single event [

13]. LaSalle and Britton add further precision by describing CX as the ensemble of customer–brand interactions—whether with a specific offering, the organization at large, or any of its constituent units—that elicit discernible cognitive, emotional, or behavioral reactions [

14]. The mechanism through which such experiences are assembled is commonly articulated via the notion of “touchpoints,” that is, the myriad occasions on which consumers “touch” or utilize a product, service, or system across multiple channels and temporal junctures [

15,

16,

17]. Stein and Ramaseshan provide an empirically grounded taxonomy of seven elemental categories manifest at touchpoints (atmospheric, technological, communicative, process, employee–customer interaction, customer–customer interaction, and product interaction), thereby underscoring the heterogeneity of stimuli that conjointly shape perceived value [

18]. Synthesising extant scholarship, Vanharanta et al. distill three overarching features of CX: its intrinsically subjective nature, dual incorporation of rational cognition and affect, and fundamentally holistic orientation that resists reduction to isolated service attributes [

19]. Gentile et al. further elucidate CX’s multidimensional structure by delineating six interrelated experiential domains: sensorial, emotional, cognitive, pragmatic, lifestyle, and relational. Each domain supplies a distinct, yet interwoven, pathway through which meaning is ascribed to brand encounters [

20]. Collectively, these perspectives position CX as a dynamic, multi-layered construct that integrates objective service design elements with subjective consumer interpretations, thereby offering a rigorous conceptual scaffold for the culturally responsive SX instrument advanced herein, where students are theorized as context-specific customers embedded within higher-education service ecosystems.

2.3. Student Experience (SX)

SX still lacks a universally endorsed definition, yet scholars consistently highlight its ubiquitous nature, noting that it frequently extends beyond strictly academic settings [

21,

22]. Conceptually, SX can be treated as a domain-specific manifestation of CX in which students act as customers engaging with the products and services supplied by HEIs, without privileging any single customer-management model. From this standpoint, SX may be defined as “all the physical and emotional perceptions and reactions that a student or prospective student experiences in response to interactions with the products, systems, or services offered by an HEI, as well as encounters with individuals connected to academic life, both within and beyond formal learning spaces” [

3]. The construct, therefore, comprises three interrelated dimensions: (i) a Social dimension concerned with community relationships and institutional engagement, covering peer-to-peer interactions, staff–student exchanges, and the attendant sense of belonging; (ii) an Educational dimension that encompasses learning engagement, perceived teaching quality, learning resources and environments, and academic support services, all of which collectively shape perceptions of institutional quality; and (iii) a Personal dimension that captures student development, emotions, identity, and background factors such as cultural heritage, socioeconomic status, disability, aspirations, family context, and leisure pursuits, each of which can modulate how services and products are experienced. This structure balances parsimony with theoretical coverage, aligns with service-science views of higher education as a value co-creation context, and resonates with prior frameworks emphasizing academic/social integration and experiential facets of learning (e.g., Tinto; Kuh; Lizzio; Astin) [

23,

24,

25,

26]. The results show that these dimensions are empirically distinguishable and substantively non-redundant, supporting their treatment as three correlated first-order factors.

Investment in SX aligns closely with UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Quality Education (SDG 4), Gender Equality (SDG 5), and Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10), thereby underscoring its strategic importance for HEIs while reinforcing institutional sustainability commitments [

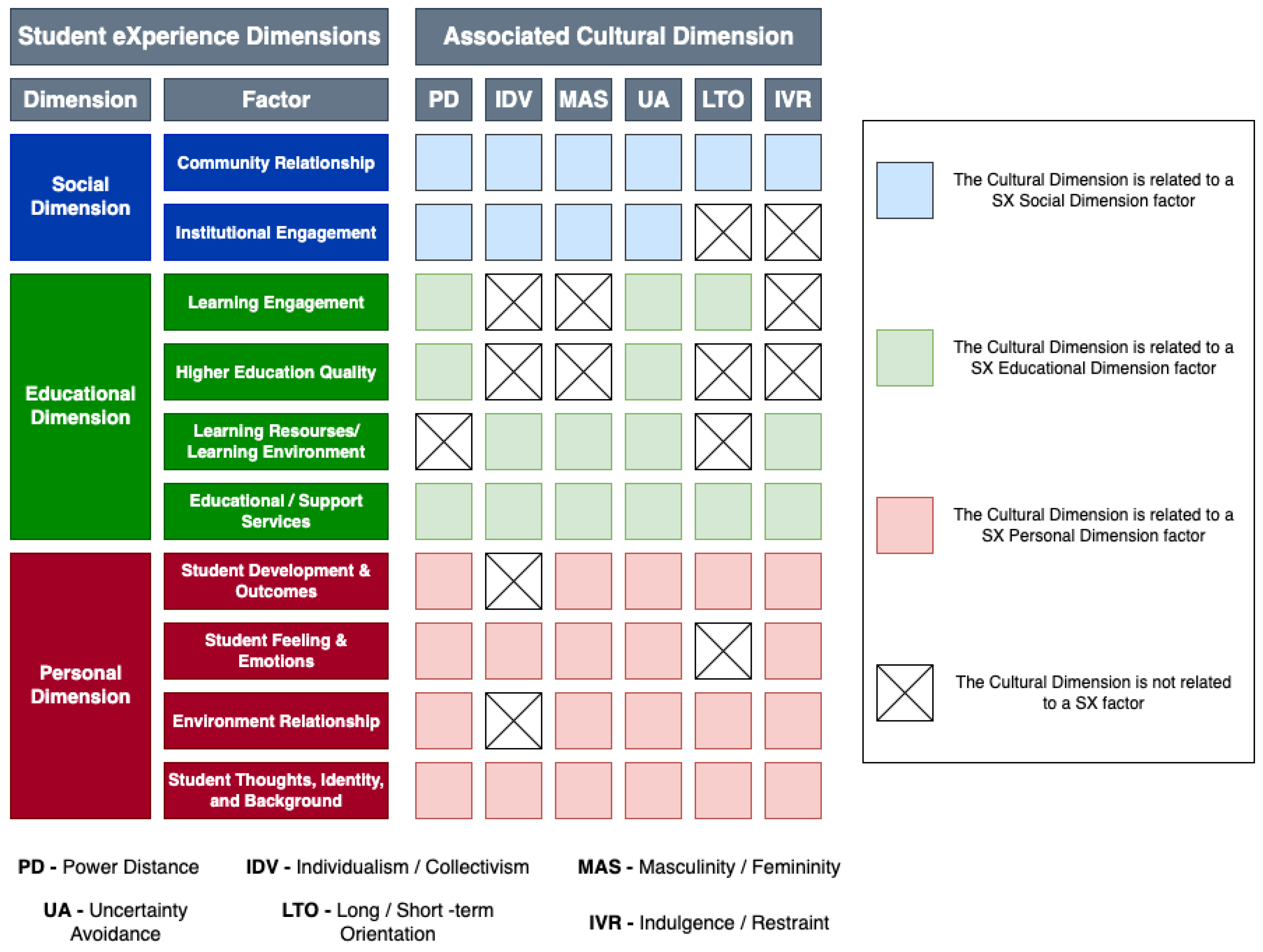

27,

28]. By explicitly integrating Hofstede’s six-dimension cultural framework into the SX model, the present work situates each cultural orientation vis-à-vis the social, educational, and personal dimensions, yielding a more inclusive, context-sensitive diagnostic instrument [

5].

2.4. Culture

Culture constitutes a foundational construct through which behavioral, ethical, and axiological divergences among societies become discernible. A survey of extant SX literature reveals that cultural factors are often treated superficially, despite their pivotal influence on student experience: cultural capital directly affects learning outcomes, and cultural identity critically shapes the adjustment processes of international, refugee, and migrant students [

29,

30,

31]. Hofstede (2010) characterizes culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” [

32]. Within the SX domain, systematic examination of students’ cultural backgrounds enables the identification of satisfaction–dissatisfaction patterns that vary by nationality and intersect with the lived realities of mobile student populations.

Guided by this rationale, the present study operationalizes on Hofstede’s six national-culture dimensions (

Table 1): Power Distance (PD), Uncertainty Avoidance (UA), Individualism–Collectivism (IDV), Masculinity–Femininity (MAS), Long- versus Short-Term Orientation (LTO), and Indulgence–Restraint (IVR). These dimensions offer a coherent framework to interpret how cultural orientations shape key aspects of SX. Specifically, PD relates to students’ comfort with authority and classroom participation; UA influences responses to ambiguity in assessment and instruction; IDV informs preferences for collaboration or autonomy; MAS aligns with attitudes toward academic competition and recognition; LTO reflects students’ goal orientation and time horizon; and IVR intersects with well-being and the regulation of leisure. Their integration into our SX model reinforces its cultural responsiveness and analytical depth.

Hofstede’s taxonomy was selected owing to its robust empirical pedigree, widespread adoption across disciplines, and the availability of practical measurement instruments [

6,

32]. We likewise considered the model’s widespread adoption in educational applications, which confers additional robustness to our proposal. Moreover, subsequent cultural frameworks often incorporate constructs conceptually consonant with Hofstede’s factors, underscoring the model’s continuing heuristic value [

33].

Recent scholarship has prompted refinements to Hofstede’s schema. Specifically, the MAS dimension has been re-labelled “Motivation towards Achievement and Success” in response to critiques that the original terminology conflated cultural values with socially constructed gender roles, reproducing gender stereotypes [

34,

35]. This terminological shift seeks to disentangle achievement-related cultural orientations from gendered assumptions, fostering a more inclusive analytical vocabulary. Such adaptations exemplify the model’s capacity for iterative revision in light of evolving theoretical and social considerations, sustaining its relevance for contemporary intercultural research agendas.

2.5. Evaluating Student Experience

Given the progressively globalized character of higher education, where students originating from markedly different cultural milieux interact with academic systems that are often foreign to their own, we deemed it essential to embed an explicit cultural lens within the SX evaluation process, a requirement that prior systematic review has underscored [

3]. Cultural orientations shape students’ cognitive frames, communication styles, and expectations of institutional support [

36]; ignoring these orientations, therefore, risks misinterpreting satisfaction scores and obscuring equity gaps. By incorporating culture-sensitive metrics and adopting an intersectional outlook, evaluators can capture heterogeneity in learning preferences and communication norms, thus mitigating biases frequently arising when standardized instruments are applied indiscriminately. This culturally attuned approach not only lends greater validity to diagnostic results but also informs more just and context-relevant policy interventions.

Guided by this rationale, we developed a theoretical SX-Cultural model (

Figure 1) that couples the canonical SX dimensions with Hofstede’s six national-culture dimensions, a framework long recognized for its explanatory power in cross-cultural research—including educational settings [

5]. Mapping SX onto Hofstede’s typology permits a nuanced appraisal of how macro-cultural schemas modulate day-to-day academic experiences, thereby revealing patterns of satisfaction and friction that vary systematically across student groups.

The SX-Cultural model further enables the design of tailored solutions, e.g., heuristics explicitly targeted at international cohorts to navigate local academic conventions [

37], or cross-cultural design guidelines that inform the development of learning technologies and service interfaces responsive to culturally differentiated needs [

38].

Building upon the SX-Cultural model, we devised a holistic evaluation methodology expressly intended to serve as a strategic diagnostic instrument for HEIs [

39]. At its core lies the multi-item evaluation scale introduced in this study, developed regarding a Spanish Latin American cultural case study [

40] and informed by the domains assessed in the United Kingdom’s National Student Survey (NSS) [

41]. We also proposed a checklist to evaluate SX [

42], and we are currently developing a set of SX heuristics. Anchored directly in the validated SX-Cultural construct, the scale preserves conceptual coherence while streamlining data collection across heterogeneous institutional contexts. Moreover, the surrounding suite of methods and instruments is deliberately modular: universities may adapt, expand, or substitute individual components in line with their strategic priorities and resource constraints without jeopardizing the theoretical integrity of the evaluation framework. Incorporating cultural analytics into SX assessment offers HEIs a rigorously substantiated and operationally flexible pathway toward fostering more inclusive, equitable, and pedagogically effective learning environments.

2.6. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

SEM is a statistical method to test complex theoretical relationships among latent constructs that are not directly measurable, accounting explicitly for measurement error. SEM accomplishes this by partitioning the observed covariance/polychoric matrix into two interconnected components: first, a measurement model which defines the relationships between observed variables (such as survey items in our case) and their underlying latent constructs (SX and Cultural dimensions); and second, a structural model, which specifies directional causal paths or associations among these latent constructs [

43,

44]. To achieve this, SEM simultaneously estimates factor loadings, representing how strongly each observed indicator is associated with its latent variable, and structural paths, capturing relationships among latent factors.

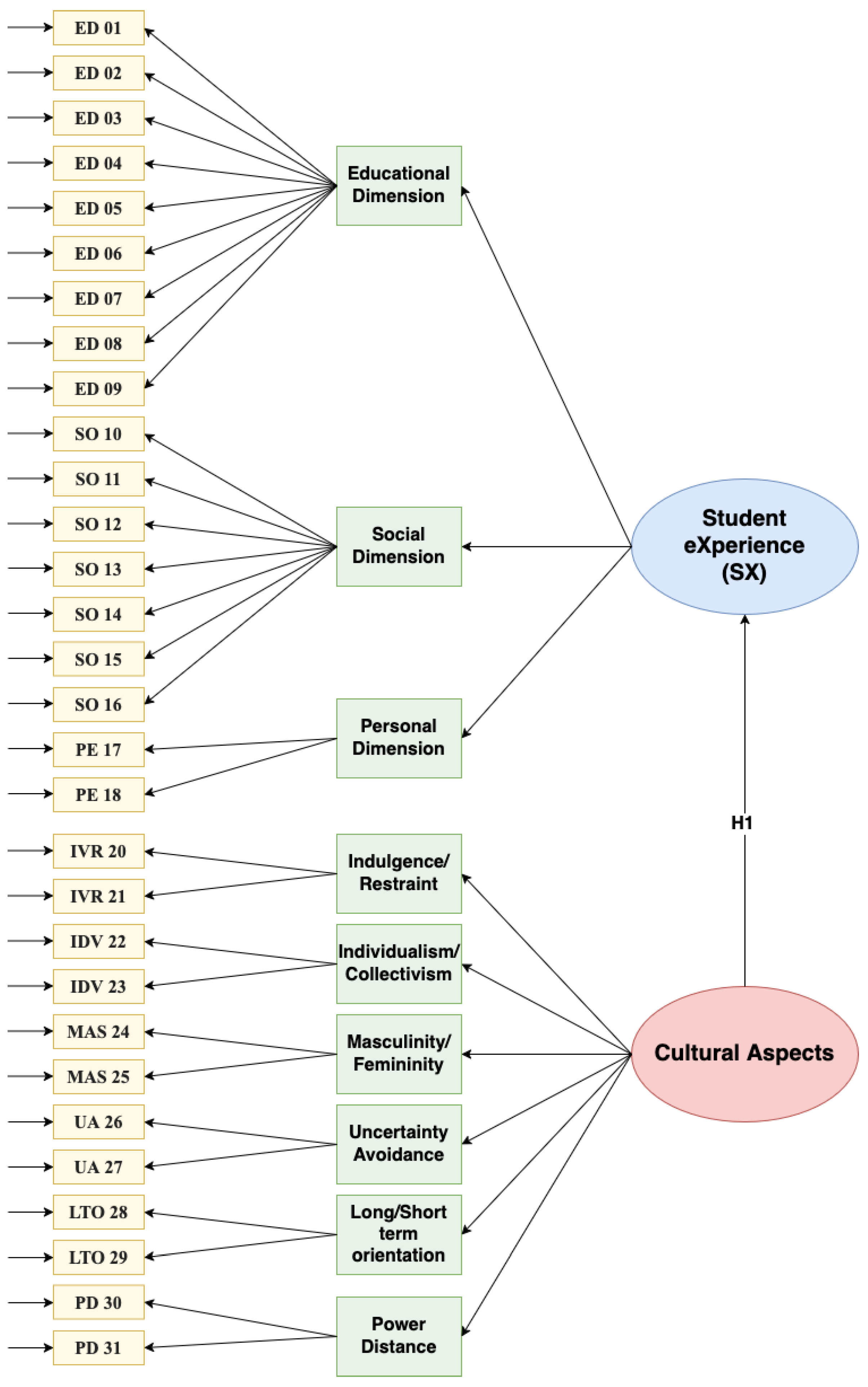

In the present study, nine first-order factors—three related to SX: Educational (ED), Social (SO), and Personal (PE); and six related to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: Indulgence/Restraint (IVR), Individualism/Collectivism (IDV), Masculinity/Femininity (MAS), Uncertainty Avoidance (UA), Long-Term Orientation (LTO), and Power Distance (PD)—load onto two higher-order constructs: SX and Cultural Aspects (CA). This hierarchical structure, consistent with contemporary factor-analytic guidelines [

45], allows SEM to rigorously assess the overarching hypothesis that cultural orientations systematically shape students’ overall perceptions and experiences at their institutions.

3. Related Studies

Recent scholarship underscores a growing reliance on SEM to elucidate the determinants of student satisfaction within HEIs. For example, Batista-Toledo and Gavilan employed SEM to examine post-pandemic commitment in blended-learning environments, isolating the structural pathways through which hybrid instruction shapes perceived satisfaction [

46]. Complementing this work, Murillo-Zamorano et al. demonstrated, via SEM, how the flipped-classroom modality enhances (or in specific contexts constrains) students’ evaluative judgements of their learning experience [

47]. Collectively, these investigations illustrate an emergent research trajectory in which SEM is used to model satisfaction metrics situated mainly within the SX’s ED dimension.

Although the extant literature often concentrates on causal relationships tied to adopting specific pedagogical tools and methodologies, SEM is equally well-suited to capturing broader and more transversal causal architectures, precisely the orientation adopted in the present study. Our evaluation scale is anchored in theoretically sound frameworks that have already been subject to extensive psychometric validation, and the empirical findings obtained in our Spanish cultural case study corroborate the scale’s construct validity and predictive utility. Consequently, the method aligns with contemporary best practices. It advances the field by demonstrating how SEM can integrate educational, social, and personal facets of SX into a comprehensive diagnostic model that informs strategic decision-making across diverse institutional contexts.

Nevertheless, a critical review of measurement approaches reveals a persistent methodological pattern: the SX is typically operationalised through self-reported instruments and generic satisfaction surveys, most of which are direct adaptations or partial derivatives of the SERVQUAL framework [

3]. This prevailing reliance on broad, service-quality templates, rather than discipline-specific or culturally nuanced scales, can attenuate construct specificity and obscure the contextual factors that drive student perceptions.

4. A Scale to Evaluate SX with Cultural Aspects

The SX-Cultural questionnaire ultimately contains 31 prompts, yet one of them, PE19, an open-ended item that invites free-text reflections on the Personal dimension, was intentionally excluded from the quantitative analyses because its qualitative nature precludes metric aggregation. The statistical validation, therefore, centers on the 30 five-point, closed-ended indicators distributed across the three Student-eXperience dimensions-Educational (ED01 to ED09), Social (SO10 to SO16), and Personal (PE17 to PE18), and the six Hofstede cultural facets, each represented by two items (IVR20 to PD31).

Item wording was refined by an interdisciplinary panel of educationists, psychologists, and UX/HCI specialists, who assessed semantic clarity, cultural relevance, and theoretical alignment before field deployment. Pilot administrations in Chile and Spain were programmed with gender-balanced quotas, following accepted survey methodology guidance to minimize sampling bias and enhance generalizability. Data collection sites were determined by university coordination and access approvals rather than by researcher selection. Within this constraint, we documented the following site characteristics: (i) accredited universities with active undergraduate programs, (ii) evidence of a multicultural student body, (iii) formal institutional authorization for data collection, and (iv) logistical feasibility (i.e., access to classes and official communication channels). Within these institutions, we employed a non-probability convenience sampling strategy.

Ordinal Cronbach’s α coefficients, computed on polychoric correlations, exceeded 0.70 for every sub-scale, and no corrected item–total correlation fell below 0.35, confirming strong internal consistency; full pilot results and reliability statistics have been reported elsewhere [

48]. All item texts, in their original Spanish and certified English translation, are provided in

Table A1, ensuring transparency and facilitating replication of this rigorously vetted 30-item SX-Cultural scale.

5. Methodology

During the 2024–2025 academic year, the 31-item scale was administered online to undergraduate cohorts at two culturally contrasting HEIs: one in Latin America and one in Spain. Of 321 submissions, 302 were fully completed, yielding an attrition rate of 5.9%. The final data set includes students from seventeen nationalities, ensuring the heterogeneity needed for cross-cultural validation. Of these respondents, 52 were ERASMUS mobility students drawn from other EU member states. Their presence adds further cultural heterogeneity beyond the host country and, thus, enhances the cross-cultural relevance of the validation exercise. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Data were collected online after obtaining formal authorization from both universities, and informed consent was included at the beginning of the scale.

We begin this section by outlining the analytic trajectory that underpins our structural equation modeling. First, we articulated a two-tier framework in which the thirty closed-ended items load on nine first-order factors that converge, respectively, on the higher-order constructs SX and cultural aspects; this specification was implemented in Jamovi (v. 2.4.8.0) using the SEMlj (v. 1.2.3) module, which leverages the Lavaan engine for latent-variable analysis.

Because every indicator is rated on a five-point scale, we employed diagonally weighted least squares with mean- and variance-adjusted statistics (DWLS/WLSMV) to estimate polychoric correlations and obtain stable parameter estimates, evaluating model adequacy against Hu and Bentler’s comparative-fit and error-fit thresholds for CFI, TLI, SRMR, and RMSEA. We then assessed measurement quality through Composite Reliability (ω), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT); modification indices were consulted, but parameters were freed only when justified theoretically, and any Heywood anomalies should be resolved by constraining factor variances or refining item wording.

Given the theoretical structure of the instrument, SEM was selected to validate both the measurement model, comprising first-order latent variables and second-order factors, and to estimate the hypothesized structural path from Cultural Aspects to SX. While Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is commonly used in early-stage instrument development, our approach was theory-driven; therefore, we prioritized Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) as a component of SEM. Moreover, SEM was necessary to account for the hierarchical latent structure and test culture-related constructs’ directional influence. The use of the WLSMV further ensured appropriate handling of the ordinal nature of the Likert-type data.

5.1. Structural Model

An articulated measurement and structural model is indispensable for two reasons: it ensures that the survey items are theoretically anchored in a specific construct and allows the analyst to disentangle substantive relations from random measurement error. Establishing this solid blueprint before testing prevents the post hoc “fishing” that often inflates fit indices and compromises generalizability. In our study, the model shown in

Figure 2 provides that foundation by mapping the questionnaire’s conceptual logic onto a two-tier structural equation framework.

H1. Higher levels of cultural congruence positively influence the perceived quality of SX in higher education contexts.

At Level 1, the 30 closed-ended items retained from the preliminary scale (ED01 to PD31) operate as observable indicators of nine first-order latent factors. Three of these factors correspond to the core SX dimensions (ED, SO, and PE) while the remaining six embody Hofstede’s cultural facets: IVR, IDV, MAS, UA, LTO, and PD. Formally, the relation is captured by Equation (1)

where

is a 30 × 1 vector of item scores, ξ is a 9 × 1 vector of first-order factors,

contains the corresponding factor loadings, and item-specific noise is isolated in ε.

At Level 2, these nine factors load on two higher-order constructs; Λ

2 is a 9 × 2 matrix of second-order factor loadings, and η is a 2 × 1 vector of second-order latent factors. Residual uniqueness at this level is captured by δ. The SX dimensions trio (ED, SO, and PE) converges on SX, whereas the six cultural facets combine to form CA, expressed in Equation (2) as

Finally, Equation (3) introduces the structural coefficient β

CA→SX, which quantifies the extent to which CA shapes SX, leaving any unexplained variance in SX to the disturbance term ζ,

Equations (1)–(3) collectively establish a two-tier SEM that isolates measurement error, consolidates related dimensions, and rigorously tests the hypothesized cultural influence on holistic student experience (

Table 2).

Item 19 was qualitative, related to the PE dimension, and it was, therefore, excluded, leaving a 30-item ordinal data set from N = 321 undergraduates enrolled at culturally contrasting universities. By embedding both measurement precision and theoretical directionality, this hierarchical model enables simultaneous evaluation of (i) the reliability and validity of each content domain and (ii) the overarching cultural effect on SX, thereby providing a methodical analytic scaffold for the empirical results that follow.

5.2. Software Tools

The statistical evaluation of the proposed structural equation models was conducted in Jamovi. This open-source graphical statistics platform interfaces seamlessly with the R ecosystem, facilitating transparent, reproducible workflows [

49]. Because the native Jamovi distribution does not include a dedicated engine for SEM, we extended its functionality by installing the SEMlj module [

50]. SEMlj serves as a thin wrapper around Lavaan, Rosseel’s widely validated R package for latent-variable analysis, providing a point-and-click interface while retaining the full analytic capabilities of lavaan’s syntax and estimation routines [

51]. This architecture allowed us to specify measurement and structural models directly within Jamovi, invoke lavaan’s robust estimation procedures (including diagonally weighted least squares for ordinal indicators), and obtain standardized parameter estimates, fit indices, modification indices, and bootstrapped confidence intervals without leaving the Jamovi environment.

5.3. Estimation Strategy and Model Fit

All survey items were measured on five-point Likert ordered-categorical scales [

52]; consequently, parameter estimation employed the DWLS/WLSMV. This estimator delivers unbiased factor loadings and standard errors under moderate sample size, ordinal indicators, and non-normal distributions, which render maximum likelihood assumptions untenable. When the initial solution yielded negative residual variances (Heywood cases), the associated latent-variable variances were fixed to 1.0, following recommended practice for achieving an admissible model while preserving the substantive interpretation of the factor structure. We also use this method because it performs well with N ≈ 300 [

51,

53].

Model adequacy was gauged with Hu and Bentler’s dual cut-offs (

Table 3): CFI/TLI ≥ 0.95, SRMR ≤ 0.08, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, while also reporting “acceptable” thresholds (≥0.90/≤0.08) to accommodate the complexity of second-order models [

54,

55].

5.4. Reliability, Convergent, and Discriminant Validity

Internal consistency was assessed with composite reliability (ω), a coefficient that remains accurate when loadings differ across items; convergent validity with AVE, the share of variance a factor captures from its indicators; and discriminant validity with HTMT, which outperforms legacy criteria in detecting conceptual overlap [

56,

57,

58].

5.5. Diagnostic Tools and Model Refinement

Anomalies such as factor loadings > 1.00 or negative error variances (Heywood cases) could be handled by constraining factor variances or inspecting item wording [

59,

60]. Modification indices (MI) were consulted but freed only when theoretically justified [

61]. Following guidelines on improper solutions, the two loadings that marginally exceeded unity within the Social dimension were retained because their residual variances remained positive, and their substantive interpretation was clear. Likewise, the three Heywood cases detected for PE, IVR, and MAS were resolved by fixing the corresponding latent variances to 1.0, an adjustment that removed the anomalies without degrading global fit (ΔCFI < 0.005).

5.6. Sample Adequacy and Future Steps

With 302 analyzable cases, the model exceeds the power thresholds recommended for similar complexity and communalities. Complete measurement-invariance testing, e.g., gender or program, is planned for future work following the ΔCFI ≤ 0.010 rule [

62].

6. Results

6.1. Data Screening and Global Model Fit

Of 321 responses, 302 were complete (attrition = 5.9%). Response distributions were balanced; skewness/kurtosis < |1| for every item.

Table 3 shows the global fit index of our proposal; classical indices signal excellent fit, and robust indices remain within the “good–acceptable” window, indicating that ordinal scaling has only a modest impact on the misfit of our model.

6.2. Measurement Model

Table 4 summarizes loadings, ω, AVE, and anomalies. All SX facets met λ ≥ 0.50 and AVE ≥ 0.50. Three cultural items (MAS24, UA27, and PD31) displayed weak or negative loadings, signaling the need for analysis or revision.

At the higher level, SX absorbed ED, SO, and PE with λ = 0.94 to 1.07, whereas CA absorbed its six facets with λ = 0.28 to 0.91 (MAS contributed least).

The measurement evidence confirms that the core SX facets are psychometrically sound, whereas items MAS24, UA27, and PD31 warrant immediate revision. These three items showed loadings below 0.50 or negative values within otherwise well-behaved factors, signaling a content-validity gap rather than a structural flaw. We, therefore, flag them for possible rewriting and/or replacement if a new version of the scale is developed; however, this does not affect the scale’s validity in its current form.

6.3. Structural Relations

The hypothesized path CA → SX was strong (β ≈ 0.92, SE = 0.06, z = 16.0,

p < 0.001) (

Table 2 and

Figure A1). A one-SD rise in aggregated cultural orientations predicts nearly a full-SD rise in perceived SX, explaining 70% of SX variance, evidence that macro-cultural schemas powerfully color day-to-day academic life.

6.4. Reliability and Validity

Six of nine first-order constructs surpassed both ω ≥ 0.70 and AVE ≥ 0.50; MAS and PD fell short (

Table 3 and

Table 5). All cross-domain HTMT values were <0.85 and within-CA values < 0.90, confirming discriminant adequacy. A Harman single-factor test yielded a poor fit (CFI = 0.39), mitigating common-method bias concerns.

Although a few items demonstrated weaker reliability, they were retained in the final scale due to their theoretical significance in representing critical aspects of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Excluding these items would have undermined the conceptual coverage of constructs such as PD and UA, essential for capturing intercultural variation in student experience. We acknowledge that theory-driven measures sometimes display lower internal consistency than empirically derived scales obtained through EFA, as they prioritize conceptual breadth over statistical optimization. In this case, including these items ensures content validity and preserves the theoretical integrity of the scale.

6.5. Residual Diagnostics and Robustness

Three Heywood cases (PE, IVR, and MAS) disappeared after fixing their latent variances to 1.0, without degrading fit (ΔCFI < 0.005). The largest MI (49) proposed correlating ED8 and ED9 (“University resources and facilities have supported my learning”/“I have been able to access specific resources and facilities whenever I needed them”); given their near-identical semantics, freeing this path would be defensible in a purely predictive model, but was withheld to keep the scale theory-driven. Re-estimating with pairwise deletion produced a virtually unchanged fit, confirming robustness to the missing-data strategy.

7. Discussion

We found that our intercultural SX scale rests on a good psychometric foundation. The hierarchical model fitted the ordinal data convincingly. CFI and TLI exceeded 0.95, while SRMR and RMSEA stayed within accepted bounds, demonstrating that our theorized structure is compatible with the response patterns of 302 undergraduates. Convergent evidence was likewise strong: all three SX dimensions and four of the six cultural facets met the recommended loading and AVE criteria, and six of the nine first-order factors reached satisfactory composite reliability. Crucially, the structural path from CA to global SX emerged extensive and precise (β ≈ 0.92), confirming that national-culture value orientations color students’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral appraisals of institutional life; the significant standardized path coefficient from CA to SX underscores the pivotal role of value orientations as perceptual lenses through which students interpret everyday academic and social encounters. Practically, the finding suggests that institutions striving to enhance experience outcomes should prioritize culturally responsive policies because these initiatives are likely to resonate across diverse student segments.

Nevertheless, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference; future longitudinal and intervention studies are needed to confirm whether modifying cultural touchpoints produces sustained improvements in SX indicators. In line with service-science perspectives, the three SX dimensions are consistent with established accounts of SX while extending them. Specifically, our results complement Kuh’s engagement [

24] and Astin’s involvement [

26] by showing that cultural orientations provide explanatory power beyond effort and participation, clarify Tinto’s academic/social integration [

23] by indicating that culture conditions how integration translates into experience, and echo Lizzio’s five senses [

25] by specifying culturally contingent antecedents of capability, connectedness, and purpose.

To our knowledge, validated SX measures seldom integrate national-culture orientations within a hierarchical SEM that jointly estimates measurement and structural relations; this study addresses that gap by modeling second-order constructs and a directional CA → SX path. To rule out the possibility that this significant coefficient is an artefact of common-method bias, we estimated a single-factor Harman model, which exhibited an inferior fit of 0.39, corroborating that the strong CA → SX link reflects substantive relations rather than methodological inflation.

The less robust performance of MAS, UA, and PD stems from narrow, single-polarity item pools and, in two cases, negatively worded statements that constrain variance (e.g., UA27 and PD31). Because these limitations did not degrade global fit or discriminant validity, we interpret them as content-validity gaps rather than structural flaws. In future iterations, we will expand these facets with balanced, context-rich items and verify their behavior through cognitive interviewing and pilot testing.

Practically, our results highlight two priorities for HEI managers. First, the strong ED and SO loadings reaffirm that investments in teaching quality, resource accessibility, and community-building deliver the most outstanding perceptual returns. Second, the magnitude of the cultural path warns against one-size-fits-all strategies; dashboards that juxtapose SX scores with cultural profiles can help anticipate divergent expectations among domestic and international cohorts.

To advance this agenda, we plan three follow-ups: (i) enrich MAS, UA, and PD with additional positively and negatively keyed statements; (ii) conduct multi-group invariance tests across gender, discipline, and nationality to ensure fair benchmarking; and (iii) link SX scores to behavioral outcomes such as retention and alumni engagement to establish predictive validity. Together, these steps will refine our scale, which already provides a rigorous, culturally nuanced lens for diagnosing and improving SX.

8. Study Limitations

Despite some constraints, our study offers a robust and meaningful first validation of a culturally responsive SX scale. The cross-sectional, self-report design does limit causal inference. Yet, it successfully captures authentic perceptions from a sizable and culturally diverse undergraduate sample, providing an essential snapshot against which future longitudinal work can be benchmarked. Focusing on two universities within two national contexts narrows external generalizability. Still, it also enables a controlled instrument test under sharply contrasting cultural profiles, an essential step before wider deployment. Measurement challenges remain, three culture-facet items loaded weakly or negatively—but the overall structure demonstrated excellent global fit, high composite reliabilities for six of nine facets, and apparent discriminant validity, indicating that the core constructs are sound even as specific items warrant refinement. Listwise deletion removed fewer than 6% of cases, and alternative estimators produced virtually identical fit statistics, suggesting that missing data did not materially distort results. Although the sample size sits near the lower bound for complex second-order SEM, the model achieved strong statistical power to detect the principal CA → SX relation, which explained 70% of variance and remained stable across robustness checks. Common-method variance was addressed empirically: the single-factor Harman test showed poor fit, supporting the distinctiveness of the measured constructs. Finally, while formal tests of measurement invariance across sub-groups await future data collections, the findings establish a preliminary baseline: the scale behaves consistently within the analyzed population and yields theoretically coherent effects. These strengths outweigh the acknowledged limitations, lending confidence to the positive results and providing a clear roadmap for incremental improvements in subsequent research phases.

9. Conclusions and Future Work

Our study demonstrates that our SX scale provides a psychometrically sound and theoretically coherent instrument for diagnosing student experience across culturally diverse higher-education settings. Sequential confirmatory-factor and hierarchical SEM analyses applied to 302 undergraduate responses achieved excellent global fit, where CFI and TLI surpassed 0.95, while SRMR and RMSEA remained within recommended limits. A strong structural path from CA to SX (β ≈ 0.92) explained roughly 70% of the variance in overall experience. Six of nine first-order constructs exceeded composite-reliability and convergent validity benchmarks, confirming that the Educational, Social, Personal, and most cultural facets are measured precisely. Content-validity gaps in MAS, UA, and PD did not compromise model integrity; instead, clear priorities for refinement were delineated. Looking ahead, we will enrich these three facets with balanced, context-rich items, conduct multi-group invariance tests across gender, discipline, and nationality, and link SX scores to behavioral outcomes such as retention and alumni engagement to establish predictive validity. By coupling canonical SX dimensions with Hofstede’s cultural lenses and outlining a concrete roadmap for iterative enhancement, we furnish researchers and practitioners with an actionable, culture-attuned diagnostic whose methodological transparency and explanatory power we expect to foster broad adoption, spur cross-institutional replications, and encourage future actions that advance global SX scholarship and institutional sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., C.R., V.R. and F.B.; methodology, N.M., C.R., V.R. and F.B.; validation, N.M., C.R., V.R. and F.B.; formal analysis, N.M., C.R., V.R. and F.B.; investigation, N.M., C.R. and F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M., C.R., V.R. and F.B.; visualization, N.M.; supervision, C.R. and F.B.; project administration, N.M., C.R., and F.B.; funding, N.M. and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Nicolás Matus was a beneficiary of ANID-PFCHA/Doctorado Nacional/2023-21230171 and was a beneficiary of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (PUCV) PhD Scholarship in Chile.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approval obtained (approved by the Ethics Committee of Comité de Ética e Integridad en la Investigación of the Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche (COIR EOM.FBB.NEMP.24) on 29 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche (UMH) and the Escuela de Ingeniería Informática (School of Informatics Engineering) of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (PUCV) for their generous disposition and the efficient administrative support that enabled the successful administration of our survey across their student populations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SX | Student eXperience |

| HEI | Higher Education Institution |

| CX | Customer eXperience |

| ED | Educational Dimension |

| SO | Social Dimension |

| PE | Personal Dimension |

| IVR | Indulgence/Restraint Dimension |

| IDV | Individualism/Collectivism Dimension |

| MAS | Masculinity/Femininity Dimension |

| UA | Uncertainty Avoidance Dimension |

| LTO | Long-/Short-Term Orientation Dimension |

| PD | Power Distance Dimension |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| CA | Cultural Aspects |

| DWLS | Diagonally Weighted Least Squares |

| WLSMV | Weighted Least Squares with Mean and Variance adjustment |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio of Correlations |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| MI | Modification Index |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

The survey items employed in this study were developed in Spanish and subsequently translated into English to facilitate broader understanding and ensure transparency regarding item content. Below, in

Table A1, we provide a side-by-side catalogue of the 30 closed-ended items retained from the original questionnaire, organized according to their respective SX dimensions: ED, SO, and PE, and the six cultural factors derived from Hofstede’s model (IVR, IDV, MAS, UA, LTO, PD). This comprehensive bilingual presentation aims to support future replications, facilitate comparative analyses across cultures and languages, and enhance the interpretability of the model parameters presented in the following sections.

Table A1.

Item Catalogue (Spanish-English).

Table A1.

Item Catalogue (Spanish-English).

| Code | Spanish Wording | English Wording |

|---|

| ED01 | Los cursos desarrollados por los profesores son interesantes | The courses delivered by faculty members are interesting |

| ED02 | Los cursos me desafían a dar lo mejor de mi al ser exigentes | The courses challenge me to do my best by being demanding |

| ED03 | Los cursos me han brindado la oportunidad de explorar conceptos en profundidad | The courses have given me the opportunity to explore concepts in depth |

| ED04 | Los cursos me han brindado oportunidades para aplicar lo que he aprendido | The courses have provided opportunities to apply what I have learned |

| ED05 | Las evaluaciones de los cursos han sido justas | Course assessments have been fair |

| ED06 | Los cursos están organizados de manera que funcionan sin problemas | The courses are organised so that they run smoothly |

| ED07 | El horario de los cursos me resulta adecuado | The course timetable is convenient for me |

| ED08 | Los recursos e instalaciones de la universidad me han servido para mi aprendizaje | University resources and facilities have supported my learning |

| ED09 | He podido acceder a recursos e instalaciones específicas cuando lo he necesitado | I have been able to access specific resources and facilities whenever I needed them |

| SO10 | He recibido comentarios útiles sobre mis trabajos académicos | I have received useful feedback on my academic work |

| SO11 | He podido contactar al personal de la universidad cuando lo he necesitado | I have been able to reach university staff when I needed to |

| SO12 | He recibido suficiente orientación en relación a mis cursos | I have received sufficient guidance regarding my courses |

| SO13 | Me siento parte de una comunidad universitaria | I feel part of a university community |

| SO14 | He tenido las oportunidades adecuadas para trabajar con otros estudiantes como parte de mis cursos | I have had adequate opportunities to work with other students as part of my courses |

| SO15 | El personal de la universidad valora las opiniones de los estudiantes | University staff value students’ opinions |

| SO16 | El centro de estudiantes representa efectivamente los intereses académicos de los estudiantes | The student union effectively represents students’ academic interests |

| PE17 | He tenido las oportunidades adecuadas para proporcionar comentarios sobre mis cursos | I have had adequate opportunities to provide feedback on my courses |

| PE18 | Estoy satisfecho/a con la calidad de mis cursos | I am satisfied with the quality of my courses |

| IVR20 | Los estudiantes tienen una visión positiva de la universidad, considerando que es posible divertirse allí | Students have a positive view of the university, believing it is possible to have fun there |

| IVR21 | Tanto profesores como estudiantes aceptan con gusto las preguntas en clase propiciando un ambiente participativo | Both professors and students readily accept questions in class, fostering a participatory environment |

| IDV22 | El sentimiento de competitividad individual entre los estudiantes es bajo; los profesores fomentan el trabajo en equipo | Individual competitiveness among students is low; lecturers encourage teamwork |

| IDV23 | Hay sentido de identidad colectivo; a los estudiantes les importan los resultados generales de las evaluaciones en los cursos | There is a sense of collective identity; students care about overall course results |

| MAS24 | Para los estudiantes es aceptable reducir sus interacciones sociales para mejorar sus resultados académicos | It is acceptable for students to reduce their social interactions to improve their academic results |

| MAS25 | La universidad ofrece recursos para los estudiantes menos favorecidos | The university provides resources for disadvantaged students |

| UA26 | Los estudiantes saben exactamente cómo serán evaluados; disponen de exámenes de años anteriores o información precisa sobre las evaluaciones | Students know exactly how they will be assessed; they have access to past exams or precise assessment information |

| UA27 | La burocracia en la universidad es un problema que consume mucho tiempo de los estudiantes | Bureaucracy at the university is a time-consuming problem for students |

| LTO28 | Los cursos se enfocan en el desarrollo profesional de los estudiantes en base a contenidos de actualidad en ingeniería/ciencia/empresa | Courses focus on students’ professional development using up-to-date engineering, science, and business content |

| LTO29 | Cuando se trata de prepararme para las evaluaciones, planifico con anticipación | When it comes to preparing for assessments, I plan ahead |

| PD30 | Existen mecanismos para que los estudiantes expresen su opinión e influyan en las decisiones de la universidad | Mechanisms exist for students to voice their opinions and influence university decisions |

| PD31 | El trato de los profesores es bastante distante; se les considera una autoridad incuestionable | Professors’ manner is rather distant; they are regarded as unquestionable authorities |

Appendix A.2

Figure A1 presents a hierarchical SEM depicting the standardized path coefficients between observed questionnaire items (yellow rectangles), first-order latent factors (green circles), and second-order latent constructs (blue and red circles). Specifically, the model integrates nine first-order latent factors: three SX dimensions (ED, SO, and PE) and six cultural dimensions based on Hofstede’s model: IVR, IDV, MAS, UA, LTO, and PD. These first-order factors load onto two second-order latent constructs: SX and CA. The structural path from CA to SX exhibits an acceptable and significant standardized coefficient (β ≈ 0.92), indicating that cultural orientations substantially influence students’ overall university experience. Solid lines represent positive loadings and structural relationships, while dashed lines denote fixed parameters or indicators for factor identification purposes. Values shown represent standardized estimates, facilitating direct comparison across paths.

Figure A1.

SEM Path Coefficients for Student Experience (SX) and Cultural Aspects (CA): Hierarchical SEM showing standardized coefficients linking items to latent factors and the strong structural path from Cultural Aspects (CA) to Student Experience (SX, β ≈ 0.92).

Figure A1.

SEM Path Coefficients for Student Experience (SX) and Cultural Aspects (CA): Hierarchical SEM showing standardized coefficients linking items to latent factors and the strong structural path from Cultural Aspects (CA) to Student Experience (SX, β ≈ 0.92).

References

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, N.; Rusu, C.; Cano, S. Student eXperience: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybinski, K. Assessing how QAA accreditation reflects student experience. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2021, 41, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matus, N.; Rusu, C.; Botella, F. Proposing a SX model with cultural factors. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo, M.T.; Hernández Gómez, J.A.; Estebané, V.; Martínez, G. Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales: Características, fases, construcción, aplicación y resultados. Cienc. Trab. 2016, 18, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, O.D. Introduction to Structural Equation Models; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Maglio, P.P.; Spohrer, J. Fundamentals of service science. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, G.; Kutsikos, K.; Sakas, D.; Nikolaos, K. Business transformation through service science: The road ahead. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laming, C.; Mason, K. Customer experience—An analysis of the concept and its performance in airline brands. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 10, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. Customer experience management: An exploratory study on the parameters affecting customer experience for cellular mobile services of a telecom company. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 133, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaSalle, D.; Britton, T.A. Priceless: Turning Ordinary Products into Extraordinary Experiences; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C.; Schwager, A. Understanding customer experience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen Norman Group. How Channels, Devices, and Touchpoints Impact the Customer Journey. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/channels-devices-touchpoints/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Nielsen Norman Group. Journey Mapping 101. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/journey-mapping-101/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Stein, A.; Ramaseshan, B. Towards the identification of customer experience touch point elements. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanharanta, H.; Kantola, J.; Seikola, S. Customers’ conscious experience in a coffee shop. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L.; Knight, P.T. Transforming Higher Education; Society for Research into Higher Education: London, UK; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arambewela, R.; Maringe, F. Mind the gap: Staff and postgraduate perceptions of student experience in higher education. High. Educ. Rev. 2012, 44, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Dropout from Higher Education: A Theoretical Synthesis of Recent Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 1975, 45, 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G.D.; Kinzie, J.; Buckley, J.A.; Bridges, B.K.; Hayek, J.C. What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature; National Postsecondary Education Cooperative: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/npec/pdf/kuh_team_report.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Lizzio, A. The Five Senses of Success: A Conceptual Framework for Student Transition and Orientation; Griffith University: Brisbane, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Astin, A.W. Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education. J. Coll. Stud. Pers. 1984, 25, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Contribution of Higher Education to the SDGs. Available online: https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/contribution-higher-education-sdgs/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- UNESCO. The 17 Goals: Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Clegg, S. Cultural capital and agency: Connecting critique and curriculum in higher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2011, 32, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, K. Global Perspectives on International Student Experiences in Higher Education: Tensions and Issues, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L.T.; Vu, T.P. Mediating transnational spaces: International students and intercultural responsibility. Intercult. Educ. 2017, 28, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Taras, V.; Rowney, J.; Steel, P. Half a century of measuring culture: Review of approaches, challenges, and limitations based on the analysis of 121 instruments for quantifying culture. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Culture Factor. Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://www.theculturefactor.com/frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Hofstede, G. Masculinity and Femininity: The Taboo Dimension of National Cultures; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, N.; Ito, A.; Rusu, C. Analyzing the impact of culture on students: Towards a Student eXperience holistic model. In Social Computing and Social Media: Applications in Education and Commerce, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference, SCSM 2022, Online, 26 June–1 July 2022; Meiselwitz, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13316, pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.; Molich, R. Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 1–5 April 1990; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Quesenbery, W.; Szuc, D. Culture and UX. In Global UX; Quesenbery, W., Szuc, D., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, N.; Botella, F.; Rusu, C. SteXMeC: A Student eXperience evaluation methodology with cultural aspects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rivero, R.; Ortiz-Marcos, I.; Patiño-Arenas, E.; Villafañe, V. Exploring the influence of culture in the present and future of multicultural organizations: Comparing the case of Spain and Latin America. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Student Survey. Available online: https://www.thestudentsurvey.com/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Matus, N.; Rusu, C.; Botella, F. A Property Checklist for Evaluating the Student Experience with Consideration of Cultural Aspects. In Social Computing and Social Media: Design, User Experience and Impact, Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCII 2025, Copenhagen, Denmark, 29 June–4 July 2025; Coman, A., Vasilache, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Toledo, S.; Gavilan, D. Student experience, satisfaction and commitment in blended learning: A structural equation modelling approach. Mathematics 2023, 11, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Zamorano, L.R.; López-Sánchez, J.Á.; Godoy-Caballero, A.L. How the flipped classroom affects knowledge, skills, and engagement in higher education: Effects on students’ satisfaction. Comput. Educ. 2019, 141, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matus, N.; Rusu, V.; Rusu, C.; Botella, F. Evaluating the Student eXperience: A Scale that Includes Cultural Dimensions. In Social Computing and Social Media: Technological and Societal Impacts, Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCII 2024, Athens, Greece, 22–27 June 2024; Coman, A., Vasilache, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi, Version 2.4. 2024. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Gallucci, M.; Jentschke, S. SEMLj: Jamovi SEM Analysis. 2021. Available online: https://semlj.github.io (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modelling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 5–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 9th ed.; Pearson: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness-of-fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Testing structural equation models. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 294–316. [Google Scholar]

- Saris, W.E.; Satorra, A.; van der Veld, W.M. Testing Structural Equation Models or Detection of Misspecifications? Struct. Equ. Model. 2009, 16, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).