1. Introduction

In recent decades, air pollution by PM has been a constant problem for public health and environmental quality at a global level, including climate regulation [

1]. In particular, PM is a great calamity for human health, since the small size of this pollutant in the air allows its unnoticed entry into the body, through one of the main means required by humans for their subsistence: breathing [

2]. These particles inhaled by people can remain for a long time in our pulmonary system, especially because they can lodge in the pulmonary alveoli [

3], which are responsible for carrying oxygen to the blood, and whose function can be diminished due to the blockage caused by these type of agents, and even some smaller particles that have the ability to pass through the alveoli and enter the circulatory system and cause other types of conditions [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In this sense, particulate matter pollution is a very worrying issue today (See

Figure 1b,c).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution is causing approximately 7 million premature deaths globally each year [

8]. In addition, the figures link 99% of the world’s population to living in densely populated areas, where the maximum permitted PM2.5 concentration standards are exceeded. Furthermore, it can be seen that this pollutant affects developing countries such as India, Nepal, Niger, Qatar, Nigeria, Egypt, Mauritania, Cameroon, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, among others, to a greater extent [

9,

10]. These figures underscore the urgent and imperative need to effectively address PM pollution to protect public health and environmental sustainability globally.

According to updated reports, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated in 2019 that ambient air pollution was responsible for approximately 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide, and about 6.7 million deaths when household air pollution is also considered [

11]. More recently, the Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health reported that pollution in all its forms, including air pollution, remains the largest environmental risk factor for health, causing close to 9 million premature deaths annually [

12]. These updated figures reinforce the urgent need for innovative approaches, such as art-based interventions, to raise awareness and mobilize action against particulate matter pollution.

In this sense, it is important to seek out different means to raise awareness of this problem. It is known that the largest burden of this pollution is generated by sources such as motor traffic and industry [

13]. All of them are linked to anthropogenic activities, which require an awakening of the population towards new ways of approaching daily life, and the making of correct decisions that help mitigate this pollutant, to improve the environment and bring improvements to the health of communities [

14,

15,

16].

Although it is a priority to raise awareness about this pollutant, in many cases the appropriate channels are not addressed and it is difficult to get the message across to the population [

7,

17,

18]. It is common to leave all this content to two large entities, science or politics. Thus, other types of actors who can provide deeper and more intimate contact with the population are left out of this type of communication process [

19,

20].

In this context, art emerges as a promising tool and an unconventional medium for communicating complex messages and mobilizing society. Through diverse artistic manifestations (

Figure 1 shows the different artistic manifestations referenced), it is possible to generate an emotional and cognitive impact that transcends the barriers of traditional scientific communication, fostering a deeper understanding and a greater willingness to take pro-environmental action [

21,

22,

23] ([

22] (p. 7)).

Unlike traditional informational approaches, which focus on the transmission of technical data on air quality and environmental risk, art offers an alternative way to mobilize knowledge through sensory experience, subjective perception, and emotion. Its ability to translate abstract or invisible concepts—such as suspended particulate matter—into visual, audio, or performative forms allows for deeper and more memorable connections with audiences. Furthermore, artistic practices promote critical reflection and active engagement from symbolic and affective perspectives, which can be key to transforming not only the cognitive understanding of the problem but also the attitudes, values, and dispositions toward action. In urban contexts marked by inequalities and environmental crises, these perceptual and emotional dimensions of art emerge as a strategic tool to foster more committed environmental citizenship [

24,

25,

26].

Given that the scientific production on the use of art as an educational and awareness-raising strategy against particulate matter pollution is still dispersed, heterogeneous, and largely recent, it was considered pertinent to conduct a scoping review. This type of review is especially useful for mapping and synthesizing emerging knowledge, exploring the nature and variety of available evidence, and identifying gaps in the literature without necessarily evaluating the methodological quality of each study. This review was carried out following the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines proposed by Tricco A.C. et al. [

27].

As Speth and Zinn (2008) have argued, addressing today’s environmental crises requires not only scientific knowledge but also a cultural and spiritual transformation [

28]. This reflection underscores the relevance of exploring unconventional communicative approaches, such as art, to foster awareness and action against complex environmental challenges like particulate matter pollution.

In this sense, it is worth asking: How does art, through educational and awareness-raising strategies, contribute to raising awareness and promoting pro-environmental actions against PM air pollution globally?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This research was conducted as a scoping review, following the guidelines of the PRISMA-ScR extension (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) to ensure transparency and rigor in the identification and synthesis of evidence. The main objective of this design is to map and characterize the existing literature on the phenomenon of interest. Therefore, the relatively small number of included studies (n = 19) should not be interpreted as a limitation of representativeness, but rather as evidence of the scarce and emerging nature of this field, which reinforces the relevance of this review.

2.2. Research Questions

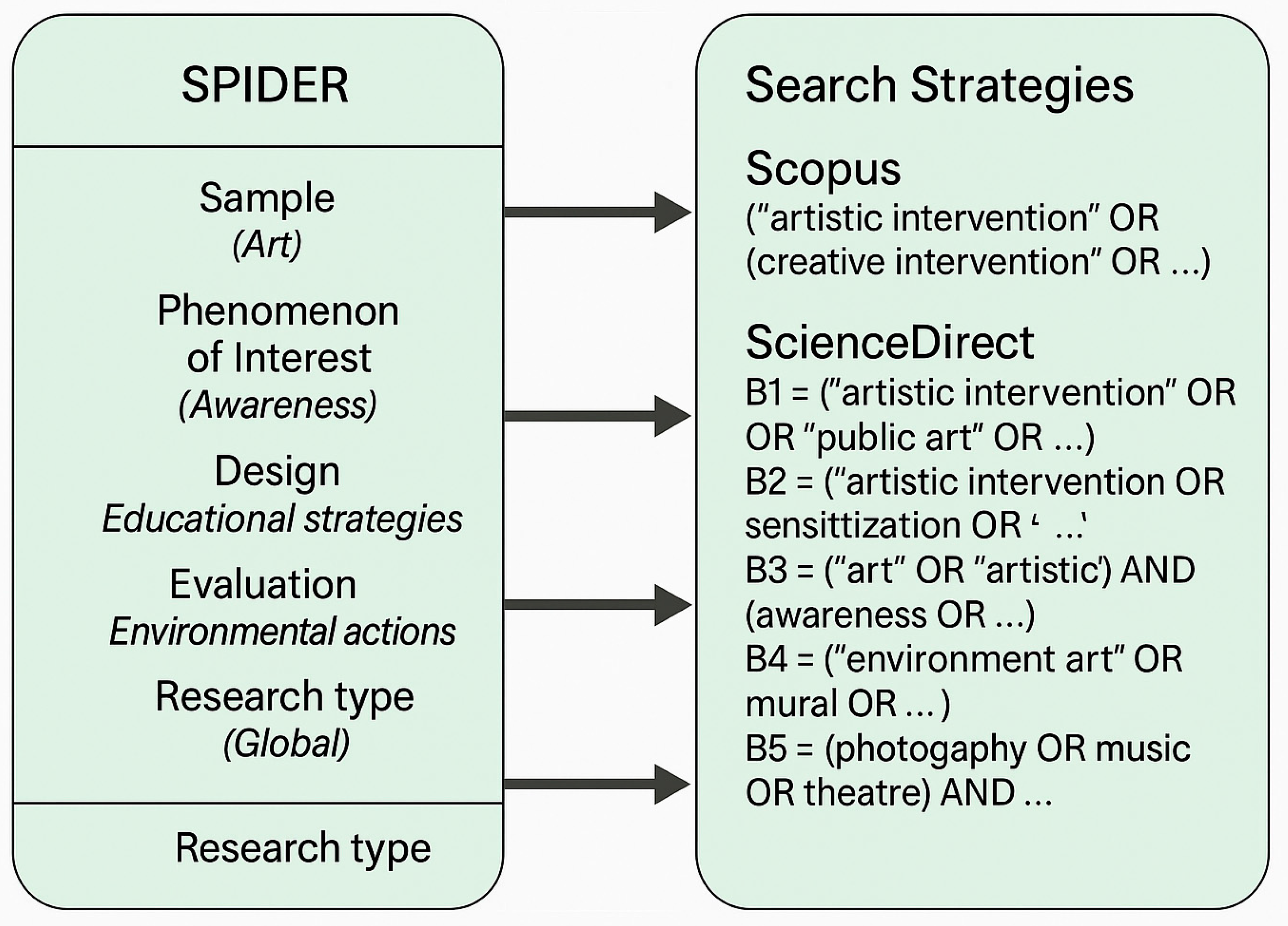

To formulate the research questions for this scoping review, the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Type of Research) framework was used (

Table 1). This approach allowed for the construction of a comprehensive main question and specific secondary questions that guided the identification and analysis of the literature.

The main research question that guided this scoping review was: “How does art contribute, through educational and awareness-raising strategies, to raising awareness and promoting pro-environmental actions against particulate matter (PM) air pollution worldwide?”.

The secondary questions addressed are as follows: First, which artistic manifestations and their inherent methodologies are most effective in conveying messages about PM pollution and its health impacts? Second, how are artistic interventions designed and implemented to integrate educational components that facilitate understanding and action on PM? Third, what evidence exists on the impact of art (through its educational and awareness-raising components) on changing attitudes, behaviors, or specific citizen participation in PM reduction or mitigation? Fourth, what are the challenges and opportunities in implementing and evaluating artistic projects that seek to raise awareness about PM pollution, especially in urban settings?

2.3. Search Strategy

Systematic research was conducted in the electronic databases Scopus and ScienceDirect. Although other databases such as PubMed were explored, no relevant articles were identified with the defined search strategy. Google Scholar, although it yielded a large volume of results, was discarded due to the impossibility of managing the large number of articles for a systematic scoping review. Likewise, the Web of Science was not accessible due to institutional limitations. Therefore, Scopus and ScienceDirect were selected as the primary and comprehensive databases for this review, given their broad coverage of the scientific literature in the areas of interest.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

The research questions were broken down using the SPIDER framework to identify key concepts and their synonyms. These terms were combined using Boolean operators (AND/OR) to construct search equations in each database. The main search string used in Scopus was as follows (

Table 2):

While most of the included studies explicitly address air pollution or PM, a small number of works focus on broader urban environmental issues (e.g., pollution perception, ecological risks, or sustainability challenges) that are directly linked to air quality. These studies were retained because their artistic interventions target public awareness and behavioral responses in contexts where air pollution and PM are significant components of the environmental problem. Their inclusion reflects the interdisciplinary character of this field and ensures a more comprehensive mapping of how art contributes to ecological literacy and civic engagement in relation to air pollution. The concept of ecological literacy refers to the ability to understand the basic principles of ecological systems and to apply this knowledge to make responsible decisions for sustainability [

29]. In this sense, ecological literacy implies not only cognitive comprehension but also the capacity to integrate environmental knowledge into everyday practices and civic action.

Due to the limitations of the ScienceDirect platform, which limits the number of Boolean operators to eight per search, it was necessary to fragment the entire search string and execute it in segments to cover all terms and ensure comprehensive search in this database. The Boolean strings used in ScienceDirect are presented in

Table 3.

The search in both databases was restricted to the following document types: articles, book chapters, and reviews. Furthermore, searches for key terms were limited to the title, abstract, and keyword fields. Searches were not limited to a specific year range, covering the literature from the start date of each database to the date of the last search. The last comprehensive search for this review was conducted on 14 July 2025.

The eligibility criteria for the study selection were developed based on the components of the SPIDER framework and the review’s research questions. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to ensure the relevance of the identified literature.

Figure 2 illustrates the methodological articulation between the components of the SPIDER framework (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Assessment, Research Type) and the construction of the search strategies applied in the Scopus and ScienceDirect databases. Each element of the framework guided the selection of key terms and Boolean operators, which were grouped into thematic blocks related to the type of artistic intervention, the educational and awareness-raising approach, and the context of particulate matter (PM) air pollution. The diagram also reflects how the searches were adapted to the technical limitations of each database, while maintaining the conceptual consistency of the methodological approach.

2.5. Inclusion Criteria

First, the study explicitly addresses the use of art (or artistic interventions, public art, environmental art, eco-art, performance art, murals, installation art, visual art, digital art, theater, dance, music) as a tool. Second, the central objective of art is to raise awareness, education, sensitization, or to promote a change in behavior or attitude related to environmental issues. Third, the topic of environmental awareness is specifically air pollution (including particulate matter—PM, PM2.5, PM10, smog, ultrafine particles, air/urban pollution, air quality). Fourth, the document types are as follows: Primary research articles, reviews and book chapters.

2.6. Exclusion Criteria

First, the article mentions “art” in the context of the “state of the art” and not as an active intervention. Second, art is an object of study (e.g., art history, art criticism, purely aesthetic analysis) and is not used as a tool for raising awareness. Third, the environmental pollution addressed is not air pollution (e.g., water pollution, soil pollution, noise pollution, etc.). Fourth, the goal of the intervention is not awareness-raising or environmental education (e.g., art for commercial purposes, purely aesthetic without awareness-raising purposes). Fifth, the following document types are excluded: Editorials, letters to the editor, opinions, essays, or conference abstracts.

To strengthen transparency and methodological rigor, the eligibility of all included studies was re-evaluated during the revision process. Only works that explicitly addressed air pollution or particulate matter were retained. In cases where the artistic intervention was framed within broader environmental issues (e.g., urban pollution or ecological risks with direct links to air quality), the rationale for inclusion was explicitly justified. This clarification ensures that the final corpus of studies is consistent with the stated scope of the review, while also acknowledging the complexity and interdisciplinarity of research that connects art, public health, and environmental awareness.

2.7. Study Selection Process

The study selection process was carried out in two main phases to identify the relevant literature. Initially, articles retrieved from the databases underwent an initial screening by title and abstract to assess their preliminary relevance based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, articles that met these criteria, or whose eligibility could not be determined from the title and abstract alone, underwent a more detailed full-text review to confirm their final inclusion.

Reference management, organization of identified articles, and duplication were performed using Zotero reference management software. It should be noted that a single reviewer (the author) carried out all phases of the screening process (title/abstract and full text). To ensure the transparency of this process, a PRISMA-SCR flowchart will be presented illustrating the number of records identified, screened, eligible, and included at each stage of the review.

It should be noted that a single reviewer (the author) carried out all phases of the screening process (title/abstract and full text). To ensure the transparency of this process, a PRISMA-ScR flowchart will be presented illustrating the number of records identified, screened, eligible, and included at each stage of the review. To minimize the potential risk of selection bias, all screening decisions and extracted information were subsequently reviewed and discussed with the co-authors, ensuring consistency with the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria and alignment with the PRISMA-ScR and SPIDER frameworks.

To further complement the PRISMA-ScR flowchart and ensure transparency in the selection process, the following

Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of the exclusion reasons and the number of records excluded at each stage.

2.8. Data Extraction

For data extraction from the ultimately included articles, a data collection form was designed to record relevant information addressing the research questions. Data extracted from each study included (but was not limited to) the following: bibliographic information (author(s), year of publication, title, country of origin of the study), characteristics of the artistic intervention (type of artistic manifestation, description of the methodology), intervention objectives, target population, reported outcomes or impacts (in terms of awareness, education, attitude/behavior change), and challenges or facilitators identified during implementation.

The information extracted from the included articles was organized and synthesized through descriptive and narrative synthesis. The objective was to map the key features of the literature and its findings to address the research questions of this scoping review.

Data were grouped and presented systematically, using a combination of descriptive text, tables, and figures, to facilitate understanding of the identified patterns and trends. Specifically, the synthesis focused on characterizing the studies according to the following factors:

General characteristics of the studies: Author(s), year of publication, country of origin, methodological design of the study (if it was a primary study).

Types of artistic interventions: Classification of the different artistic manifestations employed (e.g., murals, performances, installations, music, theater, photography, etc.) and methodologies inherent to their implementation.

2.9. Data Synthesis

Objectives and approaches of the interventions: The specific purposes of the arts initiatives (general awareness, environmental education, attitude/behavior change, community mobilization).

Target populations: The demographic groups targeted by intervention (e.g., children, youth, the community at large, decision-makers).

Reported impacts: The observed outcomes or effects in terms of increased knowledge, changes in attitudes, changes in pro-environmental behaviors, or levels of citizen participation regarding PM pollution.

Challenges and opportunities: The barriers and facilitators identified in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the arts interventions.

This approach provided a comprehensive overview of the current literature and identified areas for future research.

2.10. Bias Management

The selection and data extraction process were conducted by a single reviewer, which represents a potential source of bias in the identification and assessment of included studies. To mitigate this risk, the previously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria were rigorously applied, and detailed records of the selection process and justification for exclusions were kept. However, it is acknowledged that the lack of peer review at the initial stages could have affected the comprehensiveness or consistency in the application of these criteria. This situation is considered a significant methodological limitation, particularly regarding the reproducibility and internal validity of the review process.

3. Results

This chapter presents the main findings of the scoping review, detailing the literature selection process, the demographic characteristics of the included studies, and a comprehensive synthesis of the key themes and methodological approaches identified in the interventions.

Nineteen studies were included that addressed the use of art as an educational, communication, or awareness-raising tool regarding PM air pollution. These studies span a wide geographical range (including countries such as Greece, Italy, China, the United Kingdom, Kenya, Ecuador, Finland, Norway, the United States, India, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, and Canada, among others) and employ multiple forms of artistic expression, such as immersive installations, participatory theater, community murals, music, eco-art design, visual interventions with contaminated textiles, photography, poetry, and digital art, among others. The target populations range from vulnerable urban communities, high school students, and the public, to local political actors and visitors to public spaces. In general, the studies agree that art facilitates greater appropriation of environmental knowledge, fosters intercultural and scientific dialogue, and promotes pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Furthermore, many highlight the potential of art to stimulate citizen participation, strengthen community agencies, and build new forms of ecological literacy in the face of the risk posed by particulate matter in urban settings. This section is organized with subheadings to provide a concise and precise description of the main findings, their interpretation, and the conclusions that can be drawn from the reviewed studies [

21,

22,

23,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

3.1. PRISMA-SCR Process

The results of the search strategy and the study selection process are presented in the PRISMA-SCR flowchart

Figure 3 This flowchart systematically illustrates the different phases of the review, including the number of records identified in the databases, those excluded due to duplication and those that were screened by title/abstract and full text, until reaching the final selection of the studies included for the synthesis.

The results of the search strategy and the study selection process are presented in the Prisma-SCR flow diagram (see

Figure 3). Initially, the systematic search in the Scopus and ScienceDirect databases identified a total of 165 records. After the references management and deduplication using zero, 5 duplicate documents were eliminated, resulting in 160 unique records for the screening phase.

In the first phase of screening by title and summary, 131 documents were excluded for not complying with the criteria of inclusion or for complying with the exclusion, which left 29 records for the review of full text. Of these, 3 documents could not be recovered or downloaded due to access limitations, resulting in 26 documents evaluated to full text. Finally, in this phase of exhaustive review, two additional documents were excluded by determining that they did not correspond to types of publications such as articles, reviews or book chapters, being instead descriptions of works of art without the explicit research process and finally five documents were excluded for being “Paper Conference”.

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

The 19 studies included in this scoping review were published between 1995 and 2025, demonstrating a growing trend in research on the use of art to raise awareness and promote pro-environmental action against particulate air pollution. As illustrated in

Figure 4, most publications are concentrated in the most recent years.

Consequently, a total of 19 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included for data synthesis in this scope review.

Specifically, it is observed that in the first two decades (1995–2000, 2000–2005, 2005–2010, and 2010–2015), only one article was published in each period. A notable increase was recorded in the 2015–2020 period, with six publications, and the highest concentration was found in the most recent five-year period, 2020–2025, with nine articles. This progression suggests an emerging interest and increased research activity in this field over the past ten years.

The choropleth map in

Figure 5 illustrates the geographic distribution of affiliations among the 19 reviewed articles related to art and air pollution, highlighting the countries where the research originated or participated in. The data reveal a significant concentration of studies in the United States, with eight associations, consolidating it as the country with the greatest contribution in this field. The United Kingdom, China, and Germany also have a significant presence, with 7, 3, and 3 associations, respectively, followed by Kenya (2 associations). Other countries such as Canada, Mexico, Finland, Russia, Ecuador, New Zealand, Brazil, India, Norway, Italy, and Greece each contribute one association.

To complement this visualization,

Table 5 provides the detailed distribution of documents by country. It is worth noting that some studies involved collaborations or case analyses across multiple countries; therefore, the sum of records in the

Table 5 exceeds the total of nineteen articles included in this review.

3.3. Key Themes and Approaches

The literature included in this scoping review consisted primarily of original research articles, allowing for a detailed look at empirical studies. Reviews and book chapters were also included, enriching the understanding of the phenomenon from diverse perspectives. The specific distribution of this type of document was 17 articles, one review, and one book chapter, and strictly adhered to the methodological eligibility criteria.

In the review of the 19 documents, a broad spectrum of artistic approaches and media was identified to address environmental and socially conscious issues. Predominantly, there is a strong emphasis on public art, ranging from muralism and landscape installations to tile art projects in urban spaces. These interventions seek accessibility and direct interaction with the community to communicate messages about conservation, pollution, and climate change.

In addition to static public art, the literature highlights the use of participatory methodologies and community art. Forms such as theater (including Forum Theater), storytelling, participatory mapping, and collective creation activities are used to foster civic engagement and explore complex perceptions about the environment. These collaborative approaches demonstrate an interest in mobilizing communities and generating dialogue through immersive and reflective artistic experiences.

Regarding the environmental topics addressed, the literature review reveals that artistic interventions have been used to address various environmental problems. While the objectives of these initiatives are broad, ranging from marine ecosystem conservation and water management to promoting green corridors and climate change adaptation, a recurring and growing topic of interest is raising awareness about air pollution.

In general, artistic interventions seek to raise public awareness about the complexity of these environmental challenges. They use art to visualize abstract or invisible concepts, such as sea level rise or air quality, making the problems more tangible and understandable for diverse audiences. The goal is not only to inform, but also to evoke an emotional connection that serves as a catalyst for reflection and participation.

The fundamental purpose of these initiatives is to promote a change in pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. This is manifested in efforts to encourage the protection of endangered species, responsible resource consumption, or a greater human connection with nature. Through experimentation and participation, interventions seek to transform passive understanding into an active disposition toward sustainability, incentivizing more environmentally friendly practices and habits.

Particularly in relation to air pollution and particulate matter (PM), studies show a distinctive approach. Artistic interventions seek to make the invisible visible, allowing the public to perceive and understand the presence and implications of PM in their environment. Examples such as “Pollution Pods” demonstrate how immersive art can recreate sensory experiences of polluted air, directly impact visitors’ perceptions, and communicate the urgency of public action. The findings suggest that art has significant potential to translate complex scientific data on air quality into understandable experiences, raising awareness and motivating action in affected communities.

These interventions not only seek to inform about the existence of PM, but also to mobilize the community and foster dialogue about its impact on human health and ecosystems. By giving voice to local concerns and exploring perceptions of air quality through collaborative art projects, the goal is to build a solid foundation for anticipatory action and climate adaptation, recognizing art as a powerful tool for social engagement and environmental resilience. A summary of the 19 studies analyzed in this work is presented below in

Table 6.

To ensure transparency in the data extraction process, the studies included in this review were systematically organized in

Table 6, which summarizes the main information coded from each publication. This table represents the coding framework applied, including categories such as author, year, country, type of artistic expression, study objectives, methodological approach, and main findings. By presenting this information in a structured manner, the table facilitates reproducibility and allows readers to trace the logic of the synthesis carried out.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reaffirmation and Interpretation of the Main Findings

The results of this scoping review confirm that, although underexplored, art constitutes a versatile and increasingly recognized tool for addressing various environmental problems, with a particular emphasis on raising awareness about PM air pollution. It was evident that forms such as public art, participatory methodologies, and transdisciplinary approaches have significant potential to transform public perceptions and promote behavioral change.

However, a crucial finding of this review is the small volume of scholarly publications (19 studies across three decades) that specifically address the intersection between art and PM. This limited output, despite a recent surge in interest, reveals a significant gap in the literature and suggests that this field is still in an emerging phase of academic consolidation. In this regard, the small corpus identified is not a weakness of this review, but rather a defining feature of a scoping study: it maps what exists to highlight gaps and future opportunities for research. Beyond identifying artistic modalities, the review highlights how these interventions contribute to sustainable cognition and action. Specifically, the studies showed that art fosters ecological literacy by translating scientific data into accessible experiences, enhances eco-perception through sensorial and affective engagement, and stimulates civic participation by enabling communities to collectively reflect and respond to particulate matter pollution. In this context, affective engagement refers to the emotional involvement of individuals in awareness and learning processes. This dimension highlights how emotions and values complement cognitive understanding, strengthening personal connection with environmental issues and increasing the likelihood of sustained behavioral change [

46].

This gap raises questions about the potential reluctance of the traditional scientific community to validate art as a legitimate object of study in environmental or public health fields. The causes could include the methodological difficulty in measuring emotional or symbolic impacts, the perception of a lack of objectivity, or the lack of transdisciplinary training among researchers. In this regard, it is necessary to promote more inclusive evaluation frameworks and interdisciplinary collaborations that capture the qualitative and social richness of art as a means of environmental transformation.

4.2. Comparison with the Existing Literature

The findings of this review are consistent with the emerging literature that recognizes the potential of art to facilitate environmental communication and foster social engagement. Previous research has highlighted art’s ability to mobilize emotions, generate empathy, and overcome cognitive barriers typical of traditional science [

32,

38]. An exemplary case is the work of Sommer (2019), who developed immersive installations that translated environmental data on PM into interactive visual and auditory stimuli [

42]. These works, presented in public spaces, allowed viewers to physically perceive pollution levels in real time, generating immediate affective responses. By making the invisible visible, these interventions demonstrated the power of techno mediated art to raise environmental awareness and motivate citizen dialogue through sensorial means. In this sense, the prevalence of strategies such as public art and participatory methodologies in the identified studies is consistent with the documented effectiveness of these approaches in generating civic engagement and message ownership in diverse contexts. These findings suggest that artistic interventions do not operate solely as symbolic representations but as active catalysts for sustainable cognition and action. By stimulating both critical awareness and collective engagement, they align directly with the goals of ecological literacy and civic empowerment [

33,

37,

41].

Studies such as that by Büker et al. (2024) paradigmatically illustrate how art can function as a multisensory and participatory device to promote environmental justice [

22]. Furthermore, the incorporation of multiple artistic languages in intercultural contexts allowed participants not only to represent their experiences with air pollution but also to actively appropriate scientific knowledge and transform it into local community action. Through a series of community interventions that combined theater, photography, visual co-creation, and urban design in contexts such as Kenya, India, and Germany, the project created spaces for the convergence of scientific knowledge and local experiences. Art was not simply a channel of communication, but a practice of sociocultural mediation that made it possible to visualize the impacts of particulate matter (PM) through everyday experiences and, at the same time, promoted the empowerment of vulnerable communities.

For her part, McKinlay (2023) developed the “Insp-AIR-ation” project in New Zealand, where art and science were articulated through creative workshops on air quality [

39]. Participants—students, teachers, and residents—produced banners and visual works with environmental messages that were publicly displayed and even debated in local political settings. This intervention demonstrates how art can foster community appropriation of technical and scientific knowledge about air and stimulate active participation in mitigation actions. This articulation between artistic creation, knowledge appropriation, and political participation demonstrates how cultural interventions can expand the repertoire of strategies for urban environmental justice. However, while art has proven effective in addressing issues such as biodiversity conservation and climate change, and while the limited sample of studies in this review places a strong emphasis on raising awareness of environmental stewardship [

22,

39,

44], the systematic application and evaluation of art specifically in this field is a considerably underexplored area in the global academic literature. The scarcity of general publications on the intersection of art and environmental communication, coupled with the lack of a strong and systematic empirical base supporting the effectiveness of art in addressing specific issues such as environmental stewardship, underscores the need for more focused and rigorous research that can leverage this knowledge.

In addition to academic literature, it is important to recognize the role of mass media in shaping public awareness of air pollution. Traditional media campaigns and news outlets have played a crucial role in disseminating information about the health impacts of PM and other pollutants [

17,

18]. However, several studies emphasize that media coverage often remains limited to alarmist narratives or short-term events, which may not lead to sustained behavioral change. In this regard, artistic interventions provide a complementary and more experiential approach, capable of translating scientific evidence into sensorial and affective experiences that go beyond information dissemination. By fostering critical reflection and participatory engagement, art-based strategies may help address some of the limitations of conventional media and may encourage deeper ecological literacy.

Beyond the descriptive mapping of artistic modalities, this review highlights comparative tendencies that can inform future research. Immersive installations and participatory theater appear to generate broader impacts by combining sensory experience with collective engagement, whereas modalities such as murals, photography, poetry, and fanzines are more consistently linked to awareness and ecological literacy, with fewer indications of behavioral change. Furthermore, contextual differences emerge: community-based initiatives in Latin America and Africa tend to emphasize civic participation and social mobilization, while interventions in Europe and North America are more often framed as educational or artistic experiments. Although these tendencies cannot be generalized given the limited evidence base, they provide a preliminary framework for understanding how artistic forms and cultural settings shape the outcomes of environmental communication.

4.3. Transcendence

The findings of this scoping review have several significant implications for future research, artistic practice, and public and environmental health policy.

First, for the academic and research community, the evident paucity of formal literature on the intersection of art and environmental awareness, despite its growing practice, underscores a crucial opportunity and need for research. It is imperative to develop more robust methodologies to quantify and evaluate the social, behavioral, and cognitive impact of artistic interventions on public perception and action regarding air pollution, particularly PM. This could involve designing longitudinal studies, implementing quasi-experimental designs, or adapting impact assessment frameworks from other disciplines to capture the complexity and scope of art’s influence. Fostering a transdisciplinary research agenda that merges the arts, humanities, and sciences is critical to legitimizing and expanding this field. For artists, curators, and environmental professionals, this review validates the growing recognition of art as a powerful and accessible tool for risk communication and citizen engagement. The findings suggest that strategies incorporating public art, community engagement, and immersive approaches are particularly effective in transforming perceptions and fostering behavior change. This implies that art professionals should be considered key players in environmental communication strategies and encouraged to continue innovating their methods, seeking partnerships with scientists and public health experts to amplify the impact of their works.

Finally, for policymakers, educators, and public health professionals, this review highlights the underutilized potential of art as a vehicle for raising mass awareness about environmental health issues, such as PM2.5 pollution. Art’s ability to make the invisible visible and generate emotional responses can complement traditional data-driven communication campaigns. It is suggested that artistic and cultural initiatives be integrated into public health and environmental education programs, allocating resources to projects that demonstrate their effectiveness and encourage greater citizen participation in mitigating air pollution.

As the world faces increasingly complex environmental challenges, it is essential to expand traditional frameworks for research and action. Art not only allows us to communicate what science reveals but also activates what science cannot yet measure: sensitivity, imagination, and a sense of belonging. Recognizing and systematizing this potential is an urgent task for building more conscious, resilient, and creative societies in the face of the environmental crisis.

To synthesize these findings,

Table 7 presents a conceptual matrix linking artistic modalities with the main outcomes reported across the studies included.

As shown in

Table 7, immersive installations and participatory theater are the modalities most consistently associated with multiple outcomes, including awareness, ecological literacy, behavioral change, and civic engagement. Murals also show strong contributions to awareness and civic engagement, though with more limited evidence regarding behavioral change. Music, photography, poetry, and fanzines tend to be linked primarily to awareness and, in some cases, civic engagement, but with fewer indications of measurable behavioral change. This distribution suggests that while all artistic forms can play a role in environmental communication, some modalities, particularly those immersive or participatory in nature—may provide broader opportunities to influence both cognition and action.

4.4. Limitations

Like any scoping review, this study has certain limitations derived from its methodological design and the decisions made during the search, selection, and analytical process. First, the screening and data extraction were conducted by a single reviewer. Although the inclusion criteria and coding were based on PRISMA-ScR and SPIDER frameworks and subsequently discussed with the co-authors to ensure consistency, this procedure may still introduce a potential risk of selection bias. Future reviews would benefit from incorporating multi-reviewer protocols or inter-rater reliability checks.

Second, the literature search relied exclusively on Scopus and ScienceDirect. Institutional access restrictions prevented the inclusion of Web of Science, while gray literature was deliberately excluded to align with the quality and traceability standards expected by a Q1 journal. Additionally, the search strategy was limited to English, since it is the primary language of international scientific communication. An exploratory search in Dialnet and other databases did not reveal relevant contributions in Spanish. While these decisions may have introduced coverage bias, they do not undermine the overall validity of the mapping exercise. Future studies should expand coverage to include additional databases, gray literature, and non-English publications.

Third, the review identified only 19 eligible studies. This number reflects both the novelty and underexplored status of the intersection between art and particulate matter pollution. While this small corpus limits statistical representativeness, it also underscores the existence of a research gap and highlights the originality of this contribution. In this sense, the scarcity of studies calls for greater scholarly attention, particularly through longitudinal, comparative, and mixed-method research designs that can systematically assess the effectiveness of art-based interventions.

Finally, the included studies exhibit considerable heterogeneity in terms of methodology, disciplinary approach, and geographic scope. Most of them relied on qualitative descriptions and lacked standardized evaluation frameworks, which limit cross-context comparisons and the possibility of measuring concrete outcomes such as behavioral change or risk perception. Despite these limitations, the interdisciplinary scope and participatory nature of the reviewed interventions demonstrate the value of integrating art into environmental communication. This highlights the need for future research to adopt more rigorous and systematic evaluative frameworks while building on the creative, embodied, and affective dimensions that make art a powerful tool for raising awareness of particulate matter pollution.

5. Conclusions

This exploratory review allowed us to identify, systematize, and analyze the current state of knowledge on the use of art as an educational and awareness-raising tool regarding PM air pollution. Despite the growing recognition of art as a powerful medium for mobilizing environmental awareness, the findings show that its specific application in the context of PM remains scarce and poorly systematized in academic literature. However, the studies identified demonstrate that various artistic manifestations, particularly public art, participatory interventions, and immersive installations, have successfully translated complex scientific messages into meaningful experiences that promote reflection, dialogue, and, in some cases, pro-environmental behavior change.

The main contribution of this review lies in highlighting a significant gap between creative practice and the scientific validation of its impacts in environmental contexts. This gap represents both a challenge and an opportunity for future transdisciplinary research integrating the arts, social and environmental sciences, and public health. Likewise, the need to recognize and enhance the role of art and artists as key agents in the fight against air pollution and in building more conscious and resilient societies is reaffirmed.

This review contributes to advancing knowledge at the intersection of art, environmental education, and air pollution awareness by systematically mapping a still underexplored field. The analysis reveals specific gaps: the scarcity of studies that employ quantitative measures of effectiveness, the limited comparative research across cultural and regional contexts, and the absence of shared methodological frameworks for evaluating art-based interventions. Future research should therefore adopt mixed methods designs, incorporate longitudinal perspectives to assess lasting impacts, and develop participatory evaluation schemes that account for both cognitive and affective dimensions. By identifying these directions, the present review not only underscores the value of art as a vehicle for ecological literacy and civic engagement but also provides a roadmap for the systematic study of artistic practices in addressing particulate matter pollution.

Considering these findings, it is necessary to move toward the design of public policies and educational curricula that recognize the potential of art as a strategic tool for environmental awareness, especially in urban contexts affected by particulate matter pollution. The structured incorporation of artistic practices into environmental education and risk communication programs can strengthen the links between scientific knowledge, citizen participation, and sociocultural transformation. Future research could focus on more systematically evaluating the impact of these interventions on environmental behavior, risk perception, and community participation, using mixed methodologies and longitudinal designs to assess their reach and sustainability over time. Ultimately, this review not only illustrates the transformative potential of art as a vehicle for environmental awareness but also invites us to rethink traditional ways of communicating risk and encouraging citizen participation, proposing a more creative, sensorial, and emotional approach that complements technical and scientific rationality. Art not only informs but can also transform; it translates the invisibility of polluted air into a tangible emotional experience, which may inspire action. Thus, the review demonstrates that it may foster ecological literacy, contribute to enriching eco-perception, and encourage civic participation, making them strategic resources for promoting sustainable action and environmental justice.