Digital Social Influence and Its Impact on the Attitude of Organic Product Consumers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stimulus-Organism-Response Model

2.2. Purchasing Behavior of Organic Products

2.3. Environmental Attitude

2.4. Subjective Norms

2.5. Social Media Content

2.6. Online Member Group Support

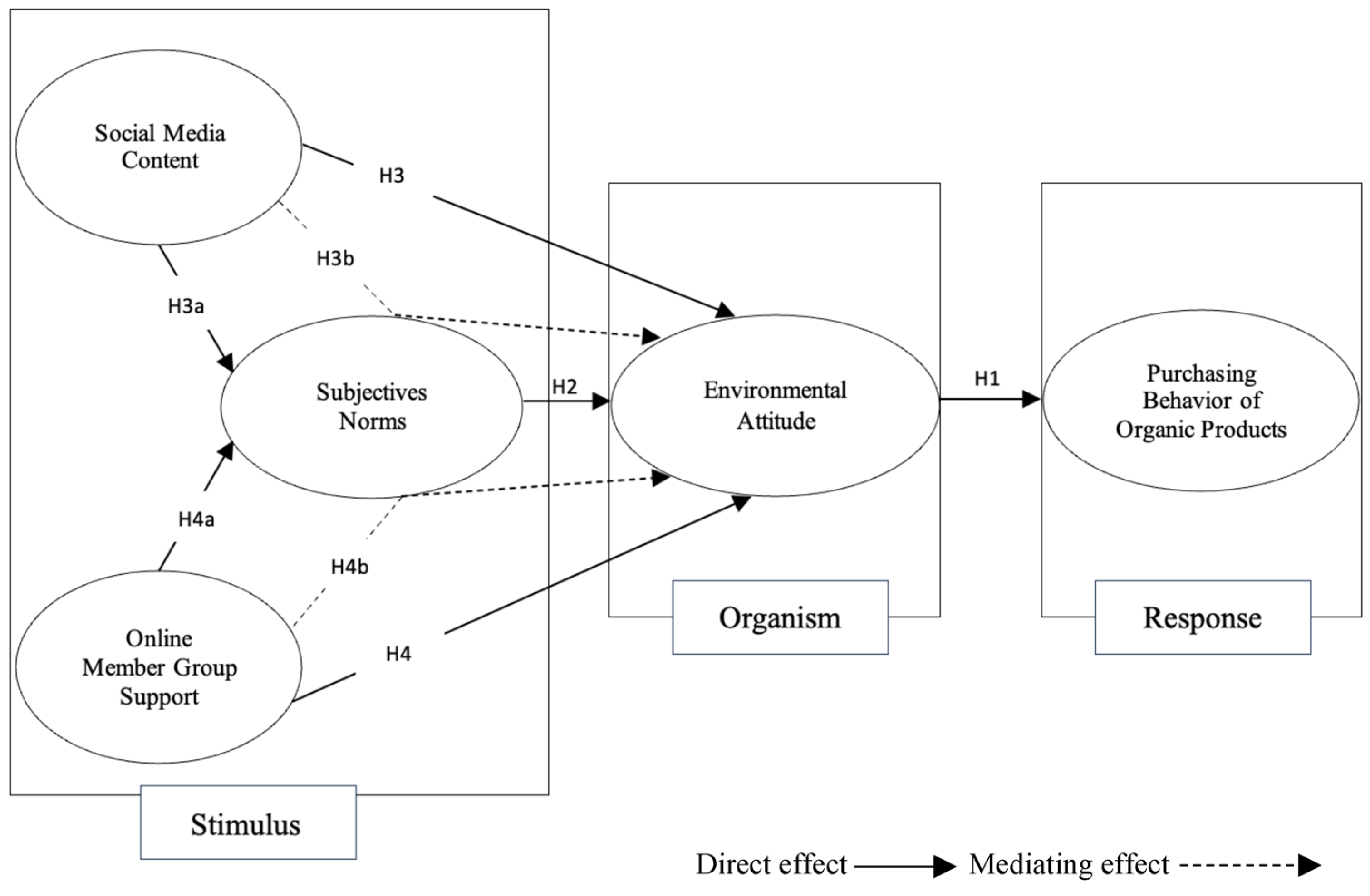

2.7. Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instrument Design and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

4.2. Baseline Transparency Supports Distributional Assessment

4.3. Estimation of the Measurement Model

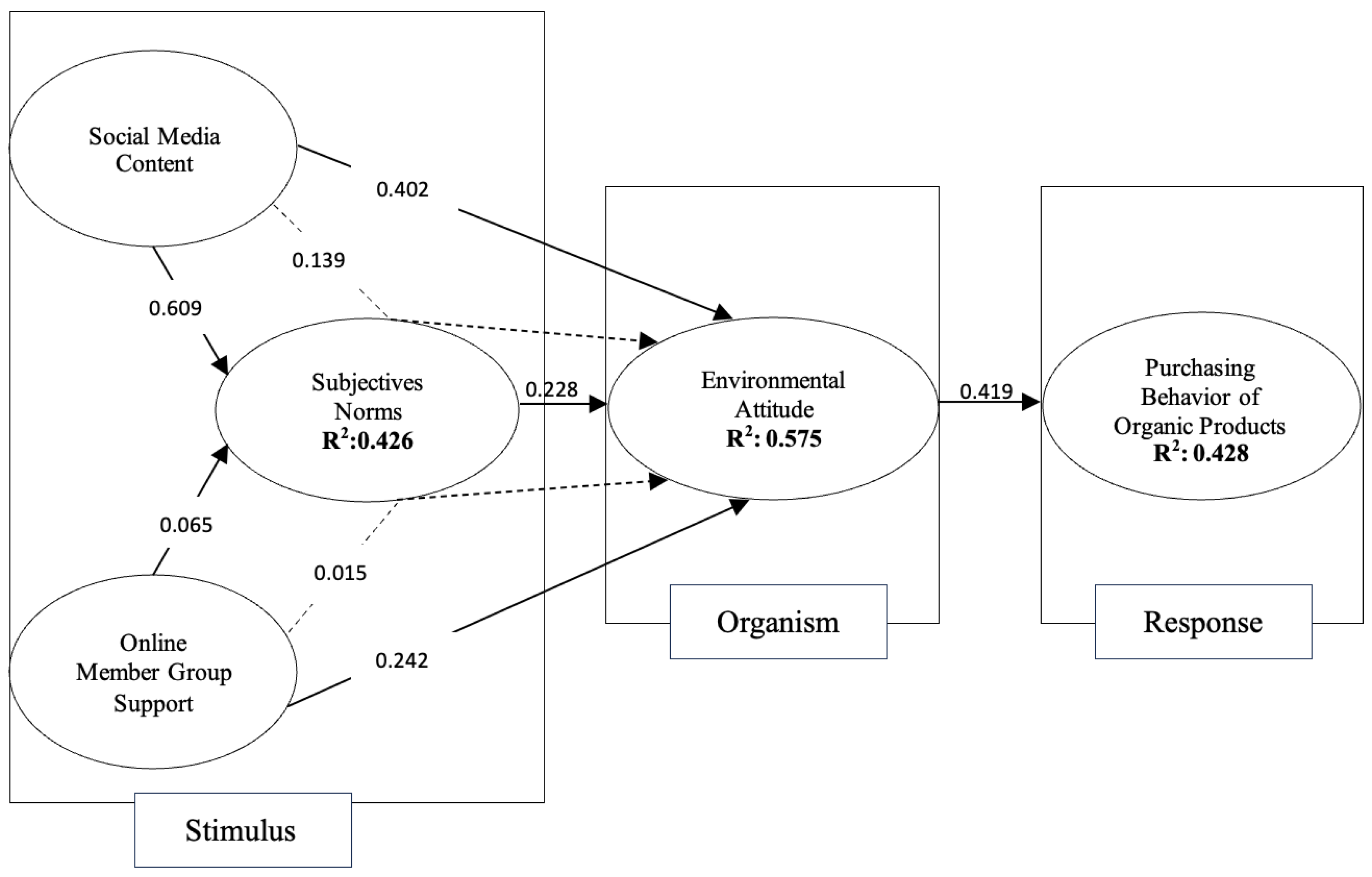

4.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): Model Fit and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Influence of EA on PBOP

5.2. Influence of SN on EA

5.3. Direct Influence of SMC on EA and Mediating Effect of SN on the Relationship Between SMC and EA

5.4. Direct Influence of OMGS on EA and Mediating Effect of SN on the Relationship Between OMGS and EA

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical, Practical, and Social Implications

6.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Questions | Author |

|---|---|---|

| SMC | SMC1: Normalmente leo información y artículos sobre temas sostenibles en las redes sociales. | Li et al. [16] |

| SMC2: Normalmente veo imágenes y vídeos relacionados con la sostenibilidad en las redes sociales. | ||

| SMC3: Normalmente escucho programas en las redes sociales relacionados con temas de sostenibilidad | ||

| SMC4: Normalmente leo anuncios y folletos del gobierno sobre políticas y estrategias sustentable en las redes sociales. | ||

| SN | SN1. Mi familia muestra una actitud positiva hacia un estilo de vida verde y sostenible en las redes sociales. | |

| SN2. Mis amigos muestran una actitud positiva hacia un estilo de vida verde y sostenible en las redes sociales. | ||

| SN3. Las personas en las redes sociales que conozco tienen actitud positiva hacia un estilo de vida verde y sostenible. | ||

| SN4. Mi universidad difunde información sobre educación verde de manera efectiva para aumentar mis conocimientos. | ||

| OMGS | OMGS1. En general, mis amigos en las redes sociales se preocupan por mí. | Saggaff et al. [80] |

| OMGS2. Mis amigos en las redes sociales me cuentan sobre productos orgánicos que me gustaría conocer. | ||

| OMGS3. Cuando pedí consejos sobre productos orgánicos, mis amigos en las redes sociales me dieron consejos útiles. | ||

| OMGS4. Siempre recibo respuestas cuando publico sobre productos orgánicos que consumo. | ||

| EA | EA1. La protección del medio ambiente es importante para mí al comprar productos. | Hoyos et al. [9] |

| EA2. Creo que los productos orgánicos ayudan a reducir la contaminación (agua, aire, etc.). | ||

| EA3. Creo que los productos orgánicos ayudan a preservar la naturaleza y sus recursos. | ||

| EA4. Si pudiera elegir, preferiría un producto orgánicos a uno convencional. | ||

| PBOP | PBOP1. He comprado productos orgánicos durante el último mes. |

References

- Sun, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhao, M. Factors and mechanisms affecting green consumption in China: A multilevel analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Sarigöllü, E. Is bigger better? How the scale effect influences green purchase intention: The case of washing machine. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larranaga, A.; Valor, C. Consumers’ categorization of eco-friendly consumer goods: An integrative review and research agenda. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yela Aránega, A.; Ferraris, A.; Baima, G.; Bresciani, S. Guest editorial: Sustainable growth and development in the food and beverage sector. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2429–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, K. Environmental Consciousness, Purchase Intention, and Actual Purchase Behavior of Eco-Friendly Products: The Moderating Impact of Situational Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Galle, W.P. Green purchasing strategies: Trends and implications. Int. J. Purch. Mater. Manag. 1997, 33, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Le, H. The effect of agricultural product eco-labelling on green purchase intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 2813–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Vallejo, C.A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; Ortiz-Regalado, O. The influence of skepticism on the university Millennials’ organic food product purchase intention. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3800–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P.; Chatterjee, S.; Ciabiada-Bryła, B. The Impact of Social Media Marketing on Consumer Engagement in Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubes, D.R.; Araújo Vila, N.; Fraiz Brea, J.A. Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafyana, S.; Alzubi, A. Social Media’s Influence on Eco-Friendly Choices in Fitness Services: A Mediation Moderation Approach. Buildings 2024, 14, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego-Arias, M.; Chávez-Rojas, E.; García-Umaña, A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Ruiz-García, W.; Guerrero-Haro, S.; Cando-Aguinaga, W. The Impact of Social Media on the Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, N.K. Impact of social media on consumer purchase intention: A developing country perspective. In Handbook of Research on the Role of Human Factors in IT Project Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 260–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, K.; Chiru, C.; Ciuchete, S.G. Exploring the eco-attitudes and buying behaviour of Facebook users. Amfiteatru Econ. 2012, 14, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chiu, D.K.W.; Ho, K.K.W.; So, S. The Use of Social Media in Sustainable Green Lifestyle Adoption: Social Media Influencers and Value Co-Creation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, A.T. The role of digital and social media marketing in consumer behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Informe General Global Digital 2022. Estadísticas de la Situación Digital de Ecuador. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-global-overview-report (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Mentino: Estado Digital Ecuador Octubre de 2024. Available online: https://www.mentinno.com/estado-digital-ecuador-octubre-2024-2/#descarga (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Armutcu, B.; Ramadani, V.; Zeqiri, J.; Dana, L.P. The role of social media in consumers’ intentions to buy green food: Evidence from Türkiye. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1923–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino Rivera, H.J.; Barcellos-Paula, L. Personal Variables in Attitude toward Green Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Foods 2024, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Distinguishing anger and anxiety in terms of emotional response factors. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J.; Eckman, M.; Yan, R.-N. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kandampully, J. The effect of atmosphere on customer engagement in upscale hotels: An application of S-O-R paradigm. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G. Stimulus–Organism–Response Model: SORing to New Heights. In Unifying Causality and Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Cho, H.J.; Turner, T.; Gupta, M.; Watchravesringkan, K. Effects of store attributes on retail patronage behaviors. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2015, 19, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya Rivas, A.; Liao, Y.-K.; Vu, M.-Q.; Hung, C.-S. Toward a Comprehensive Model of Green Marketing and Innovative Green Adoption: Application of a Stimulus-Organism-Response Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.S.; Hampson, D.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Consumer confidence and green purchase intention: An application of the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayadi, J.; Putra, E.; Murwani, I. The implementation of S-O-R Framework (stimulus, Organism, and Response) in User Behavior Analysis of Instagram Shop features on Purchase Intention. Sch. J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D. Cultural values and energy-saving attitude-intention-behavior linkages among urban residents: A serial multiple mediation analysis based on stimulus-organism-response model. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2022, 34, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, S.; Gatto, K.; Smoller, M. Consumer knowledge about food production systems and their purchasing behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 2871–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Uţă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust management in organic agriculture: Sustainable consumption behavior, environmentally conscious purchase intention, and healthy food choices. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; Verbeke, W.; Mondelaers, K.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Personal determinants of organic food consumption: A review. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1140–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, A.I.; Hurriyati, R.; Wibowo, L.A.; Monoarfa, H. Consumers in responsible consumption: What leads to sustainable behavior? Urban. Sustain. Soc. 2025, 2, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavič, P. Evolution and Current Challenges of Sustainable Consumption and Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Veas-González, I.; Naranjo-Armijo, F.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Ruiz-García, W.; Guerra-Regalado, W.; Vidal-Silva, C. Advertising and Eco-Labels as Influencers of Eco-Consumer Attitudes and Awareness—Case Study of Ecuador. Foods 2024, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Veas-González, I.; Naranjo-Armijo, F.G.; Guerra-Regalado, W.F. The mediating role of attitude and environmental awareness in the influence of green advertising and eco-labels on green purchasing behaviors. Span. J. Mark-ESIC. 2024, 29, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Vallejo, C.A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; Veas-González, I. Impact of consumption values on environmental attitudes and organic purchase intentions among Peruvian millennials. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Catană, Ș.A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.I.; Ioanid, A. Factors influencing consumer behavior toward green products: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Alam, M.N.; Alshareef, R.; Alsolamy, M.; Azizan, N.A.; Mat, N. Environmental factors affecting green purchase behaviors of the consumers: Mediating role of environmental attitude. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2023, 10, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusyani, E.; Lavuri, R.; Gunardi, A. Purchasing Eco-Sustainable Products: Interrelationship between Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Concern, Green Attitude, and Perceived Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Green purchase and sustainable consumption: A comparative study between European and non-European tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagourtas, G.; Kounetas, K.E.; Simaki, V. Consumer attitudes and sociodemographic profiles in purchasing organic food products: Evidence from a Greek and Swedish survey. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 2407–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahari, S.A.; Hass, A.; Idris, I.B.; Joseph, M. An integrated framework examining sustainable green behavior among young consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2022, 39, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Sharma, R. Study on relationships among terminal and instrumental values, environmental consciousness and behavioral intentions for green products. J. Ind. Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, S. “I buy green products for my benefits or yours”: Understanding consumers’ intention to purchase green products. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 1721–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, T.; Mata, P. Intrinsic motivation and its influence in eco shopping basket. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 6, 2812–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S. A fresh look at understanding Green consumer behavior among young urban Indian consumers through the lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Naranjo Armijo, F.; Veas-González, I.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Guerra-Regalado, W.F. Influential factors in the consumption of organic products: The case of Ecuadorian and Peruvian millennials. Multidiscip. Bus. Rev. 2024, 17, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N. Ethical consumption behavior towards eco-friendly plastic products: Implication for cleaner production. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 5, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M. Learners and Learning in Environmental Education: A critical review of the evidence. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 207–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Toro, O.N.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Palacios-Moya, L.; Uribe-Bedoya, H.; Valencia, J.; Londoño, W.; Gallegos, A. Green purchase intention factors: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2356392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.; Ali Khan, S.M.F. Assessing consumer behavior in sustainable product markets: A structural equation modeling approach with partial least squares analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, F.A.; Sosianika, A.; Suhartanto, D. Indonesian millennials’ halal food purchasing: Merely a habit? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristl, A.; Kilian, S.; Mann, A. When does a social norm catch the worm? Disentangling social normative influences on sustainable consumption behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Yusta, A.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.P.; Pérez-Villarreal, H.H. Studying the impact of food values, subjective norm and brand love on behavioral loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pandey, M. Social Media and Impact of Altruistic Motivation, Egoistic Motivation, Subjective Norms, and EWOM toward Green Consumption Behavior: An Empirical Investigation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Njite, D.; Hancer, M. Anticipated emotion in consumers’ intentions to select eco-friendly restaurants: Augmenting the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D.K. How environmental concerns influence consumers’ anticipated emotions towards sustainable consumption: The moderating role of regulatory focus. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, B.K.; Lobo, A.; Vu, P.A. Organic food purchases in an emerging market: The influence of consumers’ personal factors and green marketing practices of food stores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Mohammed, S.; Haroon, M.; Noor, M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.K. Predicting unethical behavior: A comparison of the theory of reasoned action of the theory of planned behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Deshaies, P.; Cuerrier, J.; Pelletier, L.; Mongeau, C. Ajzen and Fishbein’s theory of reasoned action as applied to moral behavior: A confirmatory analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.; Gensler, S.; Leeflang, P. Popularity of brand posts on brand fan pages: An investigation of the effects of social media marketing. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletikosa, I.; Michahelles, F. Online engagement factors on Facebook brand pages. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2013, 3, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R. Influence of social media marketing communications on young consumers’ attitudes. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthouse, E.; Haenlein, M.; Skiera, B.; Wege, E.; Zhang, M. Managing customer relationships in the social media era: Introducing the social CRM house. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthouse, E.; Calder, B.; Kim, S.; Vandenbosch, M. Evidence that user generated content that produces engagement increases purchase behaviours. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Frethey, C.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media engagement behavior: A framework for engaging customers through social media content. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2213–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrum, K. “Hey friend, buy green”: Social media use to influence Eco-purchasing involvement. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lee, Y.; Lien, N. Online social advertising via influential endorsers. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 16, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Khan, A.; Nabi, M.; Khanam, Z.; Arwab, M. The effect of ewom on consumer purchase intention and mediating role of brand equity: A study of apparel brands. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2023, 28, 1108–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K. A comparative study of green purchase intention between Korean and Chinese consumers: The moderating role of collectivism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, S.A.N.; Tolmie, C.R. Millennials’ green consumption behaviour: Exploring the role of social media. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hassan, N.M.; Sheikh, A. Unboxing the dilemma associated with online shopping and purchase behavior for remanufactured products: A smart strategy for waste management. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihab, M.S.; Ikhsan, R.B.; Fakhrorazi, A. The power of social media: Exploring online member groups and psychological factors to support responsible consumption. Digit. Bus. 2025, 5, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W.; Wien, A. A framework for categorizing social media posts. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1284390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nick, E.; Cole, D.; Cho, S.; Smith, D.; Carter, T.; Zelkowitz, R. The Online Social Support Scale: Measure development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 1127–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lee, S.H.; Copeland, L.R. Social media and Chinese consumers’ environmentally sustainable apparel purchase intentions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, B.; Afiff, A.Z.; Heruwasto, I. The role of norms in predicting waste sorting behavior. J. Soc. Mark. 2021, 11, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, M.S.; Cheok, M.Y.; Alenezi, H. Assessing the impact of green consumption behavior and green purchase intention among millennials toward sustainable environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 23335–23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.F.; Alanadoly, A.B. Personality traits and social media as drivers of word-of-mouth towards sustainable fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2021, 25, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 4; SmartPLS: Oststeinbek, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H.O. Soft Modeling: The Basic Design and Some Extensions. In Systems Under Indirect Observations: Part II; Joreskog, K.G., Wold, H.O.A., Eds.; Systems Under Indirect Observations: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 1–54. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=2333614 (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Cuenca | 99 | 26.7 |

| Guayaquil | 74 | 19.9 | |

| Quito | 92 | 24.8 | |

| Santo Domingo | 106 | 28.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 178 | 51.2 |

| Female | 190 | 48.8 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Age range | 1978 or earlier (X Generation) | 42 | 11.3 |

| Between 1979 and 1988 (Older Millennials) | 68 | 18.3 | |

| Between 1989 and 1994 (Mid Millennials) | 31 | 8.4 | |

| Between 1995 and 2000 (Younger Millennials) | 71 | 19.1 | |

| After 2000 (Centennials) | 159 | 42.9 | |

| Educational Level | Bachelor’s degree | 277 | 74.7 |

| Postgraduate degree | 94 | 25.3 |

| Variable | Item | Loading Factor | AC | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rho_a | rho_c | |||||

| Environmental Attitude | AC1 | 0.913 | 0.892 | 0.892 | 0.892 | 0.822 |

| AC2 | 0.921 | |||||

| AC3 | 0.886 | |||||

| Subjective Norms | SN1 | 0.899 | 0.858 | 0.859 | 0.914 | 0.779 |

| SN2 | 0.872 | |||||

| SN3 | 0.877 | |||||

| Social Media Content | SMC1 | 0.836 | 0.847 | 0.853 | 0.897 | 0.686 |

| SMC2 | 0.813 | |||||

| SMC3 | 0.780 | |||||

| SMC4 | 0.880 | |||||

| Online Member Group Support | OMGS1 | 0.761 | 0.775 | 0.789 | 0.853 | 0.592 |

| OMGS2 | 0.783 | |||||

| OMGS3 | 0.778 | |||||

| OMGS4 | 0.756 | |||||

| Purchasing Behavior of Organic Products | PBOP1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Variables | AC | SN | SMC | OMGS | PBOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 0.906 | 0.694 | 0.823 | 0.737 | 0.656 |

| SN | 0.607 | 0.882 | 0.762 | 0.559 | 0.589 |

| SMC | 0.716 | 0.653 | 0.828 | 0.829 | 0.552 |

| OMGS | 0.627 | 0.481 | 0.684 | 0.769 | 0.523 |

| PBOP | 0.620 | 0.545 | 0.510 | 0.469 | 1 |

| Hypotheses | Relation | β | p-Values | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EA-PBOP | 0.419 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | SN-EA | 0.218 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3 | SMC-EA | 0.402 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3a | SMC-SN | 0.609 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3b | SMC-NS-EA | 0.139 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4 | OMGS-EA | 0.242 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4a | OMGS-SN | 0.065 | 0.296 | Rejected |

| H4b | OMGS-NS-EA | 0.015 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Roldán, G.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.; García-Umaña, A.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Medina-Miranda, S.; Marchena-Chanduvi, R.; Llamo-Burga, M.; López-Pastén, I.; Veas González, I. Digital Social Influence and Its Impact on the Attitude of Organic Product Consumers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167563

García-Roldán G, Carrión-Bósquez N, García-Umaña A, Ortiz-Regalado O, Medina-Miranda S, Marchena-Chanduvi R, Llamo-Burga M, López-Pastén I, Veas González I. Digital Social Influence and Its Impact on the Attitude of Organic Product Consumers. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167563

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Roldán, Geovanna, Nelson Carrión-Bósquez, Andrés García-Umaña, Oscar Ortiz-Regalado, Santiago Medina-Miranda, Rubén Marchena-Chanduvi, Mary Llamo-Burga, Ignacio López-Pastén, and Iván Veas González. 2025. "Digital Social Influence and Its Impact on the Attitude of Organic Product Consumers" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167563

APA StyleGarcía-Roldán, G., Carrión-Bósquez, N., García-Umaña, A., Ortiz-Regalado, O., Medina-Miranda, S., Marchena-Chanduvi, R., Llamo-Burga, M., López-Pastén, I., & Veas González, I. (2025). Digital Social Influence and Its Impact on the Attitude of Organic Product Consumers. Sustainability, 17(16), 7563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167563