Climate Change Projects and Youth Engagement: Empowerment and Contested Knowledge

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Climate Change and Differential Vulnerabilities of Youth

1.1.2. Climate Change and Youth Empowerment

1.2. Education and Empowerment

1.3. Educational Gamification

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Engagement Process

2.2.1. PowerPoint Presentation

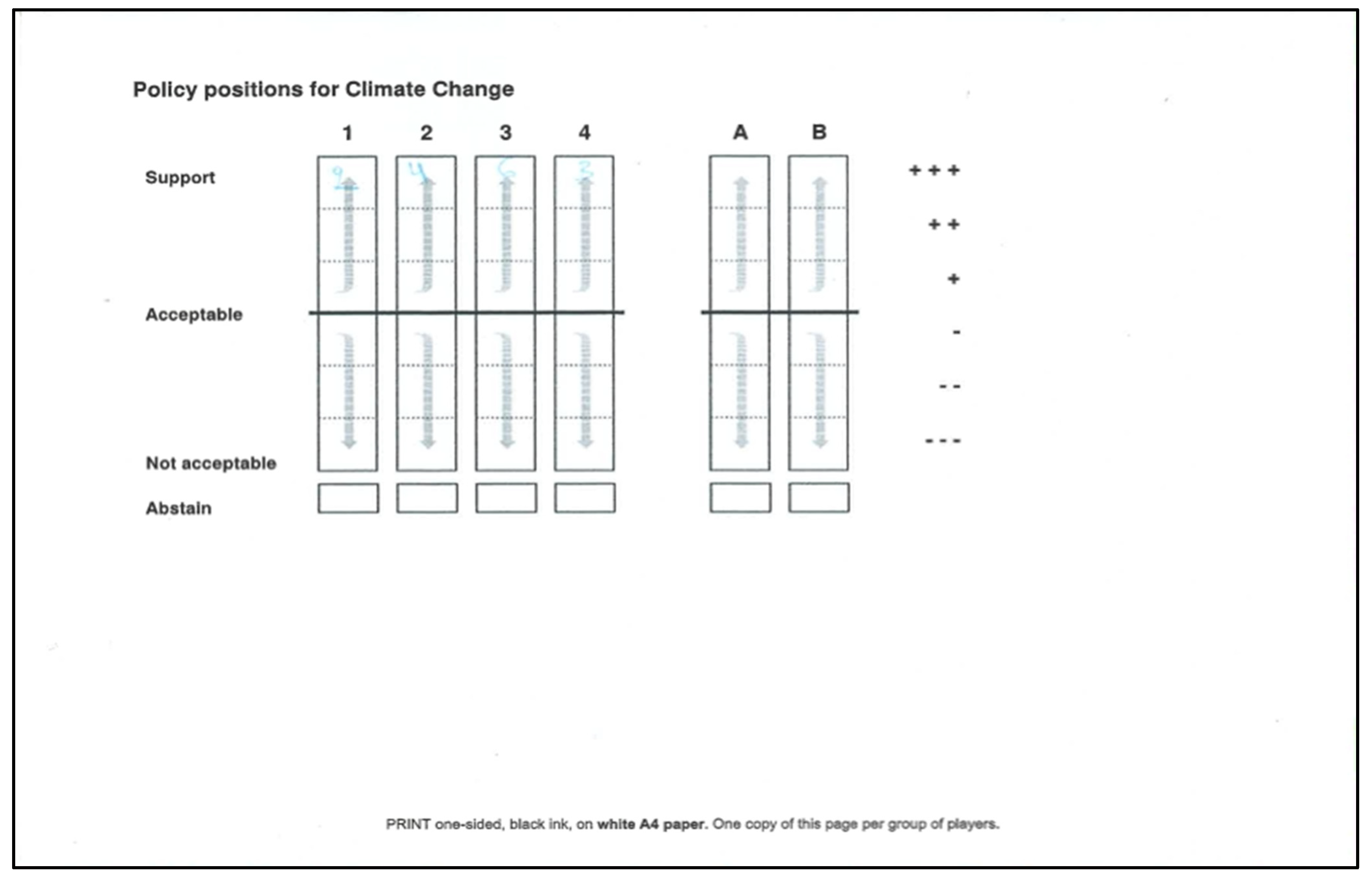

2.2.2. PlayDecide Card Game

2.2.3. Science Museum Educational Visit

2.3. Ethics Statement

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Limitations

3. Results

3.1. PlayDecide Card Game

3.1.1. Uncertainties and Alternative Conceptions

“Where we create… global warming… climate change”.[S5]

“Which means that the gases that exist in greenhouses are present in the atmosphere”.[S5]

“Well, I read, I saw a video somewhere anyway, some people from China went to the moon, and they dug inside the moon, and they found a fuel that is much smaller, covers much more energy, produces energy and if they bring it, they intend to bring this to earth and use it”.[S3]

“One gram I think they said covers New York (energy needs); I think for two months”.[S3]

3.1.2. Complexities

“The biggest desert is the Sahara. So, this is barren land, no one steps on it right? The sun shines there 24/7, if you fill this with photovoltaics won’t you power all of Greece?”[S1]

“You will extract (the energy) but the grid will not be able to pick up all that energy from a certain point”.[S2]

“The only problem is who has the cash”.[S4]

“Also, if the Sahara is filled with photovoltaics, the life that exists in the Sahara will also decrease”.[S2]

“I believe that this moon is not such a good idea, because sending rockets into space is not the most ecological (sustainable) thing. By the time the rockets arrive, come out of the atmosphere, the carbon dioxide they release is very large amounts, so imagine one rocket going off every month”.[S1]

“Hey people, it is how we consume first and then look at the moon and the rest”.[S7]

3.1.3. Concerns

“The fact that we have already adapted to climate change and, of course, the damage has been done, it is very difficult to completely remove carbon dioxide from our lives. I mean, I had seen somewhere, I had read that by 2050 we have to reduce carbon dioxide emissions to zero to stop climate change, which is not going to happen, so adapting is the best thing”.[S1]

“Will we reach fifty years of age”?[S5]

“Most politicians look out for their own interests”.[S8]

“… no matter how many photovoltaics we put in, no matter how much money we give, no matter what we do, they (politicians) will find another way to spend money again and be in their own interest. So, I think the best thing would be to discuss with a large group of people who have a lot of influence, if we are a very large group of people, we can make a change”.[S5]

3.2. Science Museum Educational Visit

3.2.1. Facilitation Dynamics

“Nuclear is the safest, most reliable, clean and cheap source from which we can get electricity and energy in general… Nuclear is the most ecological source of energy, but we don’t use it. Wind turbines are a very safe source of energy, not so efficient and take up a lot of space. Hydroelectric is a lousy source of energy”.[F]

“I want to ask, because the house we live in and the plot will be expropriated, with the fee we will get…[S]

… will the expropriation be fair? Isn’t that what you want to say?[F]

Other than that, will there be other land available that is not affected by the wind farm?”[S]

3.2.2. Expertise

“The engineer’s study will tell you that if is managed correctly, because Greenpeace is Kostas, Giannis, Lefteris, Eleonora and Dimitra, this is Greenpeace. It (Greenpeace) has some people who have a scientific background, but it is not a scientific position, like the other weird Belgians who are against wind. Okay? It’s Mr. Giannis, Mrs. Tasoula and Eleni or the mayor. It’s not some scientists who say it, it’s groups of citizens.”[F]

“So the study of an engineer is the only scientific one. Ok? They may be thorough, they may not be, you may trust them, you may not trust them, but the most reliable of the three (NGOs, residents, engineer) is the study.”[F]

“How do we know that they are telling the truth, and they are not part of you? We want an engineer of our own.”[S]

3.2.3. Public Participation

“Obviously as active citizens you have to go and position yourself, regardless of whether you are an expert on the subject, you have an obligation to have an opinion, you don’t have to be right, okay?”[F]

“In essence, this discussion is not for you to decide to be in favor. This discussion is to convince you to be in favor. And that’s what it’s always for.”[F]

“Guys, democracy means that when there are new arguments, we change our opinion… I was wrong and now I believe something else”.[F]

“That is, if, say, we hold a competition for the recruitment of new employees for the new positions that are to be opened, and we reward the locals in points, so that they can be appointed more easily, will you change your vote?[F]

“Maybe yes”[S]

“Maybe yes, very nice. This negotiation is not unethical. The other thing the guys were saying before, “what will they give us to change the vote” is unethical. Do we understand the difference between immoral and moral? It may look the same, it’s not. Because the argument is my wife will lose her job, we are here and you are breaking us up, there is the counter argument, if we help hire local people first. He has an argument that makes more sense.”[F]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCUS | Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Islam, N.; Winkel, J. Climate Change and Social Inequality; UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.; Hardy, R.D.; Lazrus, H.; Mendez, M.; Orlove, B.; Rivera-Collazo, I.; Roberts, J.T.; Rockman, M.; Warner, B.P.; Winthrop, R. Explaining differential vulnerability to climate change: A social science review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2019, 10, e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, V.; von Hirschhausen, E.; Fegert, J.M. Report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: Implications for the mental health policy of children and adolescents in Europe—A scoping review. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 31, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Van Hoorn, J.; Burke, S.E. Responding to the impacts of the climate crisis on children and youth. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, G.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S. ‘Seeing with Empty Eyes’: A systems approach to understand climate change and mental health in Bangladesh. Clim. Change 2021, 165, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barford, A.; Mugeere, A.; Proefke, R.; Stocking, B. Young People and Climate Change; The British Academy: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.; Forte, C.L.; Fraser, E.M. UNHCR’s Engagement with Displaced Youth. A Global Review. Geneva: UNHCR. 2013. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/513f37bb9.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Kitanova, M. Youth political participation in the EU: Evidence from a cross-national analysis. J. Youth Stud. 2020, 23, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, L.B.; Calton, J.M.; Brodsky, A.E. Status quo versus status quake: Putting the power back in empowerment. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 42, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, U.X.; Jiménez-Morales, M.; Soler Masó, P.; Trilla Bernet, J. Exploring the conceptualization and research of empowerment in the field of youth. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 22, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Launches the Youth Empowerment Fund: New Partnership with the World’s Largest Youth Organisations to Support Young People Contributing to the SDGs. Available online: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/eu-launches-youth-empowerment-fund-new-partnership-worlds-largest-youth-organisations-support-young-2023-10-04_en (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- O’Flaherty, M. What Do Fundamental Rights Mean for People in the EU? European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klaniecki, K.; Leventon, J.; Abson, D.J. Human–nature connectedness as a ‘treatment’for pro-environmental behavior: Making the case for spatial considerations. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Berry, H.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W. The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. Lancet 2018, 392, 2479–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemot, J.; Burgess, J. Child Rights at Risk. 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/928-child-rights-at-risk-the-case-for-joint-action-with-climate-change.html (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Banerjee, A.; Peterson, S.; Dalglish, S.L.; Ameratunga, S.; Balabanova, D.; Bhan, M.K.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Borrazzo, J. A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 395, 605–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.; Kemper, J.A.; White, S.K. No future, no kids–no kids, no future? An exploration of motivations to remain childfree in times of climate change. Popul. Environ. 2021, 43, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, K.; Hayward, B.; Aoyagi, M.; Burningham, K.; Hasan, M.M.; Jackson, T.; Jha, V.; Kuroki, L.; Loukianov, A.; Mattar, H. Youth attitudes and participation in climate protest: An international cities comparison frontiers in political science special issue: Youth activism in environmental politics. Front. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 696105. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Ahn, S.W. Youth mobilization to stop global climate change: Narratives and impact. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soßdorf, A.; Burgi, V. “Listen to the science!”—The role of scientific knowledge for the Fridays for Future movement. Front. Commun. 2022, 7, 983929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, H.; Loy, L.S. What drives pro-environmental activism of young people? A survey study on the Fridays For Future movement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 74, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parth, A.-M.; Weiss, J.; Firat, R.; Eberhardt, M. “How dare you!”—The influence of Fridays for future on the political attitudes of young adults. Front. Political Sci. 2020, 2, 611139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Action for Climate Empowerment. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/education-and-youth/big-picture/ACE (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- European Commission. European Youth for Climate Action; European Commission: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, B.; Chaskin, R.J.; McGregor, C. Promoting civic and political engagement among marginalized urban youth in three cities: Strategies and challenges. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.; Schott, S. Knowledge coevolution: Generating new understanding through bridging and strengthening distinct knowledge systems and empowering local knowledge holders. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.E. Crafted within liminal spaces: Young people’s everyday politics. Political Geogr. 2012, 31, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, M.; Patrikios, S. Making democracy work by early formal engagement? A comparative exploration of youth parliaments in the EU. Parliam. Aff. 2013, 66, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prev. Hum. Serv. 1984, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; McCowan, T. Higher education and the sustainable development goals. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentz, J.; O’Brien, K. ART FOR CHANGE: Transformative learning and youth empowerment in a changing climate. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2019, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtis-Kazoullis, V.; Gouvias, D.; Oikonomakou, M.; Skourtou, E. The Creation of a Community of Language Learning, Empowerment, and Agency for Refugees in Rhodes, Greece. In Springer International Handbooks of Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Le, K.; Nguyen, M. How education empowers women in developing countries. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 21, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H.A. Rethinking education as the practice of freedom: Paulo Freire and the promise of critical pedagogy. Policy Futures Educ. 2010, 8, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.B. John Dewey and American Democracy; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cury, C.R. Anísio Teixeira (1900–71); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education; Macmillan New York: New York, NY, USA, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Ardoin, N.M. Toward an interdisciplinary understanding of place: Lessons for environmental education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. (CJEE) 2006, 11, 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Revised); Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Volume 356, pp. 357–358. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, C.; Henriksen, E.K.; Hansen, P.J.K. Climate education: Empowering today’s youth to meet tomorrow’s challenges. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2005, 41, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigota, M. Environmental education in Brazil and the influence of Paulo Freire. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spínola, H. Environmental education in the light of Paulo Freire’s pedagogy of the oppressed. PLoS Sustain. Transform. 2023, 2, e0000074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for the future? Critical evaluation of education for sustainable development goals. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Reis, P.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Činčera, J.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Gericke, N.; Knippels, M.-C. Conceptualizing Environmental Citizenship for 21st Century Education; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, V.; Carson, K. Introducing argumentation about climate change socioscientific issues in a disadvantaged school. Res. Sci. Educ. 2020, 50, 863–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, F.S.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M.; Torabi, E. Can public awareness, knowledge and engagement improve climate change adaptation policies? Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, C.D. Children’s constructive climate change engagement: Empowering awareness, agency, and action. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veyne, P. Foucault: His Thought, His Character; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, C. Authority Is Relational: Rethinking Educational Empowerment; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, J.; Cornwall, A. Power and knowledge. In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 172–189. [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola, I. The problem of terminology in the study of student conceptions in science. Sci. Educ. 1988, 72, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.; Freyberg, P. Learning in Science. The Implications of Children’s Science; Heinemann Educational Books, Inc.: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Niyogi, D.; Shepardson, D.P.; Charusombat, U. Do earth and environmental science textbooks promote middle and high school students’ conceptual development about climate change? Textbooks’ consideration of students’ misconceptions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 91, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, F. Evaluation of geography textbooks in terms of misconceptions about climate topic. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2019, 9, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.; Macnaghten, P. Traditional ecological knowledge in innovation governance: A framework for responsible and just innovation. J. Responsible Innov. 2020, 7, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Adem, Ç.; Alangui, W.V.; Molnár, Z.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Bridgewater, P.; Tengö, M.; Thaman, R.; Yao, C.Y.A.; Berkes, F. Working with indigenous, local and scientific knowledge in assessments of nature and nature’s linkages with people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 43, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stori, F.T.; Peres, C.M.; Turra, A.; Pressey, R.L. Traditional ecological knowledge supports ecosystem-based management in disturbed coastal marine social-ecological systems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, N.; Nakamura, H.; Hamzah, A. Adaptation to climate change: Does traditional ecological knowledge hold the key? Sustainability 2020, 12, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens, a Study of the Play-Element in Culture; Roy: Oxford, England, 1950; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Hutt, S.J.; Tyler, S.; Hutt, C.; Christopherson, H. Play, Exploration and Learning: A Natural History of the Pre-School; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, P.; Doyle, E. Gamification and student motivation. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1162–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponetto, I.; Earp, J.; Ott, M. Gamification and Education: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Berlin, Germany, 9–10 October 2014; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2014; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos, A.; Mystakidis, S. Gamification in education. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 1223–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaffas, A.; Kaabi, K.; Shadiev, R.; Essalmi, F. Towards an optimal personalization strategy in MOOCs. Smart Learn. Environ. 2020, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, The personalization of e-learning systems with the contrast of strategic knowledge and learner’s learning preferences: An investigatory analysis. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2021, 17, 153–167. [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, J.; Knittle, K.; Ginchev, T.; Khattak, F.; Helf, C.; Zwickl, P.; Castellano-Tejedor, C.; Lusilla-Palacios, P.; Costa-Requena, J.; Ravaja, N. Engaging users in the behavior change process with digitalized motivational interviewing and gamification: Development and feasibility testing of the precious app. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajer, N.; Earnest, J. Youth empowerment for the most vulnerable: A model based on the pedagogy of Freire and experiences in the field. Health Educ. 2009, 109, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.; Freire, T. Positive youth development in the context of climate change: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 786119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupkiolis, A.; Pechtelidis, Y. Youth heteropolitics in crisis-ridden Greece. In Young People Re-Generating Politics in Times of Crises; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 273–293. [Google Scholar]

- Pantazidi, E. Navigating Uncertainty: An Exploration of Young Adults’ Lives in Post-Crisis Athens, Greece–Socioeconomic Conditions, Challenges, Adaptation, and Future Aspirations. Master’s Thesis, University of Padua, Padua, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Krommyda, V.; Gialis, S.; Stratigea, A. Climate crisis and labour market inequalities: A socio-ecological fix approach to energy transition in Greece. In Research Handbook on Inequalities and Work; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 540–554. [Google Scholar]

- Ivaldi, E.; Antonicelli, M. Deprivation and Regional Cohesion as Challenges to Sustainability: Evidence from Italy and Greece. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse-Biber, S.N.; Leavy, P. Emergent Methods in Social Research; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Agell, L.; Soria, V.; Carrió, M. Using role play to debate animal testing. J. Biol. Educ. 2015, 49, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PlayDecide About PlayDecide. Available online: https://playdecide.eu/about (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Macdonald, S.H.-F.; Egan, K.; Shé, É.N.; O’Donnell, D.; McAuliffe, E. The PlayDecide Patient Safety game: A “serious game” to discuss medical professionalism in relation to patient safety. Int. J. Integr. Care (IJIC) 2019, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Ní Shé, É.; De Brún, A.; Korpos, C.; Hamza, M.; Burke, E.; Duffy, A.; Egan, K.; Geary, U.; Holland, C. The co-design, implementation and evaluation of a serious board game ‘PlayDecide patient safety’to educate junior doctors about patient safety and the importance of reporting safety concerns. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PlayDecide. PlayDecide Card Game. 2021. Available online: https://playdecide.eu/en (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Chen, H.-L.; Wu, C.-T. A digital role-playing game for learning: Effects on critical thinking and motivation. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 3018–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Cui, Y.; Chiu, M.M.; Lei, H. Effects of game-based learning on students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2022, 59, 1682–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 2, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszna, P.; Galus, A. Promoting active youth: Evidence from Polish NGO’s civic education programme in Eastern Europe. J. Int. Relat. Dev. 2020, 23, 210–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.; Benevento, A. Epistemic justice as a political capability of radicalised youth in Europe: A case of knowledge production with local researchers. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2022, 23, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, P.M.; Levinson, R.; Li, X. Informed-decision regarding global warming and climate change among high school students in the United Kingdom. Can. J. Sci. Math. Technol. Educ. 2021, 21, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.C.; Sorensen, A.E.; Gray, S.A. What undergraduate students know and what they want to learn about in climate change education. PLoS Sustain. Transform. 2023, 2, e0000055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, E.K.; Jorde, D. High school students’ understanding of radiation and the environment: Can museums play a role? Sci. Educ. 2001, 85, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Cherry, L. Enlisting the power of youth for climate change. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamatia, P.L. The Role of Youth in Combating Social Inequality: Empowering the Next Generation. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Econ. Agric. Res. Technol. 2023, 2, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitt, S.; Axsen, J.; Long, Z.; Rhodes, E. The role of trust in citizen acceptance of climate policy: Comparing perceptions of government competence, integrity and value similarity. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, M.; Sevä, I.J.; Kulin, J. Political trust and the relationship between climate change beliefs and support for fossil fuel taxes: Evidence from a survey of 23 European countries. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 59, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, N. Political generations and the Italian environmental movement(s): Innovative youth activism and the permanence of collective actors. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 63, 1556–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotti, F.; Donato, S.; Bussoletti, A.; Comunello, F. Youth activism for climate on and beyond social media: Insights from FridaysForFuture-Rome. Int. J. Press/Politics 2022, 27, 718–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J. What is youth political participation? Literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Front. Political Sci. 2020, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S.T. Environmental trust: A cross-region and cross-country study. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, N.-S.; Chen, G. Effects of teacher role on student engagement in WeChat-Based online discussion learning. Comput. Educ. 2020, 157, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.R. Implementing curriculum guidance on environmental education: The importance of teachers’ beliefs. In Curriculum and Environmental Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 298–314. [Google Scholar]

- Veugelers, W. The moral in Paulo Freire’s educational work: What moral education can learn from Paulo Freire. J. Moral. Educ. 2017, 46, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, N. Promoting ethics and morality in education for equality, diversity and inclusivity. J. Multidiscip. Cases 2021, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebeker, M.L. The teacher and society: John Dewey and the experience of teachers. Educ. Cult. 2002, 18, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Milovanovic, J.; Shealy, T.; Godwin, A. Senior engineering students in the USA carry misconceptions about climate change: Implications for engineering education. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 345, 131129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnovsky, M.; Hasson, K. CRISPR’s Twisted Tales: Clarifying Misconceptions about Heritable Genome Editing. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2020, 63, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, D.B. Integrating social sciences and humanities in interdisciplinary research. Palgrave Commun. 2016, 2, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, S.P.; Muhonen, R. Who benefits from ex ante societal impact evaluation in the European funding arena? A cross-country comparison of societal impact capacity in the social sciences and humanities. Res. Eval. 2020, 29, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stavrianakis, K.; Nielsen, J.A.E.; Morrison, Z. Climate Change Projects and Youth Engagement: Empowerment and Contested Knowledge. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167556

Stavrianakis K, Nielsen JAE, Morrison Z. Climate Change Projects and Youth Engagement: Empowerment and Contested Knowledge. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167556

Chicago/Turabian StyleStavrianakis, Kostas, Jacob A. E. Nielsen, and Zoe Morrison. 2025. "Climate Change Projects and Youth Engagement: Empowerment and Contested Knowledge" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167556

APA StyleStavrianakis, K., Nielsen, J. A. E., & Morrison, Z. (2025). Climate Change Projects and Youth Engagement: Empowerment and Contested Knowledge. Sustainability, 17(16), 7556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167556