1. Introduction

Fiscal policy and monetary policy constitute the primary instruments within the macroeconomic regulatory framework, serving a pivotal function in the execution of macroeconomic governance in China. At present, the Chinese economy demonstrates stability and steady advancement, with notable achievements in high-quality development. Nonetheless, it confronts a range of risks and challenges, including inadequate domestic effective demand; persistent pressures to stabilize employment, enterprises, markets, and expectations; diminished efficacy of conventional policy measures; as well as compounded risks arising from the hidden debts of small and medium-sized financial institutions and local governments. Given these complexities, reliance on either fiscal or monetary policy in isolation is insufficient. Therefore, it is imperative to enhance the coordination between monetary and fiscal policies to effectively mitigate these challenges [

1].

The coordination of monetary and fiscal policies is a crucial topic within contemporary macroeconomic research. The majority of investigations into the coordination between fiscal and monetary policies are grounded in five principal perspectives. First, the significance of policy coordination has intensified in response to evolving macroeconomic conditions, including negative population growth, accelerated demographic aging, and the reduction in government debt [

2,

3]. Second, there is an increasing scholarly focus on the integration of fiscal and monetary policies with other policy domains, such as macro-prudential regulation, industrial policy, and employment strategies [

4,

5]. Third, heightened academic interest has emerged due to the heterogeneity of the macroeconomic environment, characterized by substantial risk shocks [

6], structural demand shocks [

7], and the diverse nature of economic agents [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Fourth, potential conflicts between the objectives of fiscal and monetary policies are examined through a game-theoretic lens [

12]; for example, employing the policy game analysis framework developed by Bodenstein et al. [

13], several studies explore the effects of competition and cooperation between fiscal authorities and monetary institutions [

14,

15]. Finally, research has focused on identifying optimal approaches to achieving policy objectives through the combined application of various fiscal instruments and monetary policy measures [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Previous research has predominantly concentrated on the interaction between the central bank’s monetary policy and the central government’s fiscal policy. In contrast, this study primarily examines the coordination between the central bank’s monetary policy and the fiscal policies implemented by local governments. Existing literature has largely overlooked this aspect, mainly due to a failure to recognize two critical features of contemporary China’s economy: the increasing significance of local governments resulting from the Chinese-style fiscal decentralization framework, and the rapid expansion of the bond market, which has been largely propelled by the financing demands of local governments. Next, we will provide a detailed analysis of these two features.

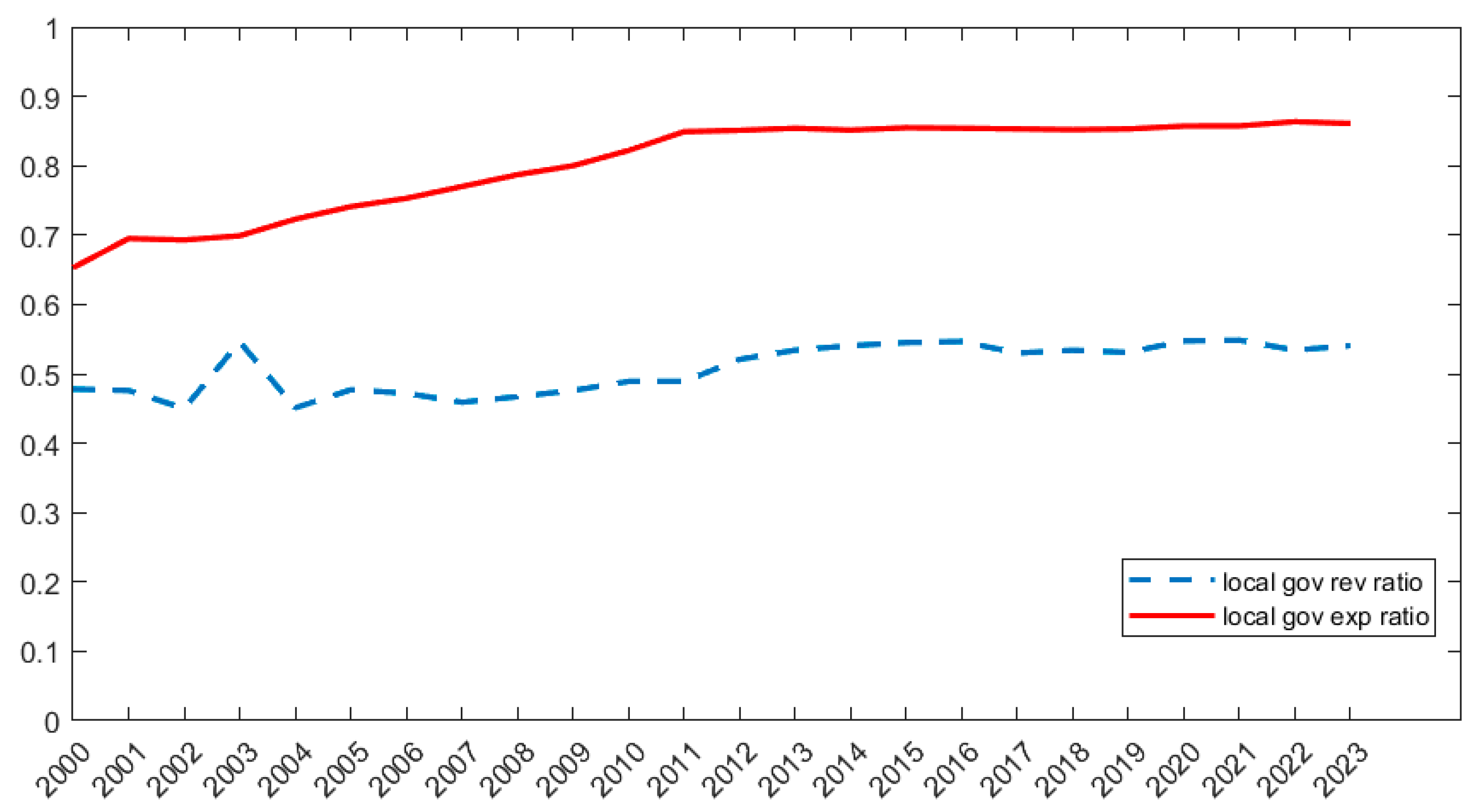

The first feature is the marked enhancement in the role of local governments. Since the implementation of tax-sharing reform, the fiscal relationship between China’s central and local governments has experienced a profound transformation. Local governments serve as the principal agents responsible for fiscal expenditures. As illustrated in

Figure 1, expenditures by local governments constitute approximately 85% of the total government expenditure. This substantial decentralization of fiscal resource control to local authorities has led to the localization of the macroeconomic control system. Following the tax-sharing system’s reform, local governments have been endowed with considerable autonomy in managing regional affairs, thereby progressively reducing the central government’s exclusive control over fiscal resources [

22]. Local governments are the primary executors of fiscal revenue and expenditure decisions within a Chinese-style fiscal decentralization system [

23]. It is essential to acknowledge that the primary roles of local governments in China diverge from those of local (state) governments in developed market economies. Specifically, Chinese local governments emphasize economic growth as a central objective, which is vital for comprehending local governance dynamics, whereas local governments in developed economies tend to focus more on the provision of public goods [

24].

The second feature is the rapid expansion of the local government bond market. Following the implementation of the Ministry of Finance’s “opening the front door and blocking the back door” policy in 2015, local governments gained the authority to publicly issue local government bonds. According to data disclosed on the official website of the Ministry of Finance of China, the projected budgeted local government debt was expected to reach CNY 47.54 trillion by the end of December 2024. Additionally, local governments have encountered vertical budget imbalances as a consequence of localization of the macroeconomic control system. As depicted in

Figure 1, local governments face substantial budget deficits, with their expenditures constituting nearly 85% of total government spending, while revenues represent only 50%. The primary contributors to these budget deficits are transfers from the central government and borrowing by local governments. The increasing demand for local government funding, driven by budget deficits and economic development, has significantly accelerated the growth of the local government bond market.

The distinctive features of the Chinese economy call for a new theoretical perspective for studying the coordination of monetary and fiscal policies in China, with particular emphasis on the coordination of the central bank’s monetary policy and local government fiscal policy. Beyond theoretical considerations, research on the coordination of the central bank’s monetary policy and local government fiscal policy can also aid in addressing practical economic challenges. The absence of such coordination has been linked to several issues in China’s recent economic development, including the diminishing efficacy of monetary policy, the excessive debt of local governments, and the rise in regional systemic risks [

25]. Consequently, the effectiveness of macroeconomic regulation is profoundly affected by the degree of coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies.

Exploring the reasons for the lack of coordination between monetary policy and local fiscal policy is essential for enhancing our comprehension of the mechanisms governing this coordination. Given the increasing significance of local governments and the rapid growth of their bond markets, two primary factors contribute to the lack of coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies in China: the conflicting goals pursued by the central bank and local governments, as well as competition among local governments. Next, we will provide a detailed analysis of these two factors.

One reason for this lack of coordination is the divergence in objectives between the central bank and local governments. Vertical fiscal imbalances compel local governments to implement flexible fiscal plans that prioritize the interests of their respective jurisdictions [

26]. In contrast, the central bank designs monetary policy with a emphasis on the overall macroeconomic environment. As a result, the goals of the central bank and local governments often conflict, particularly when the central bank implements a tightening monetary policy by raising the policy interest rate to curb aggregate demand. Meanwhile, the pressures of economic growth resulting from political competition motivates local governments to adopt expansionary fiscal policies, characterized by increased government expenditure and debt accumulation. However, in the current context of declining policy interest rates, monetary and local government fiscal policies may exhibit greater coordination, as the interests of the central bank and local governments begin to converge. An accommodative monetary policy reduces borrowing costs for local governments, thereby affording them greater flexibility to advance their fiscal initiatives, as illustrated in

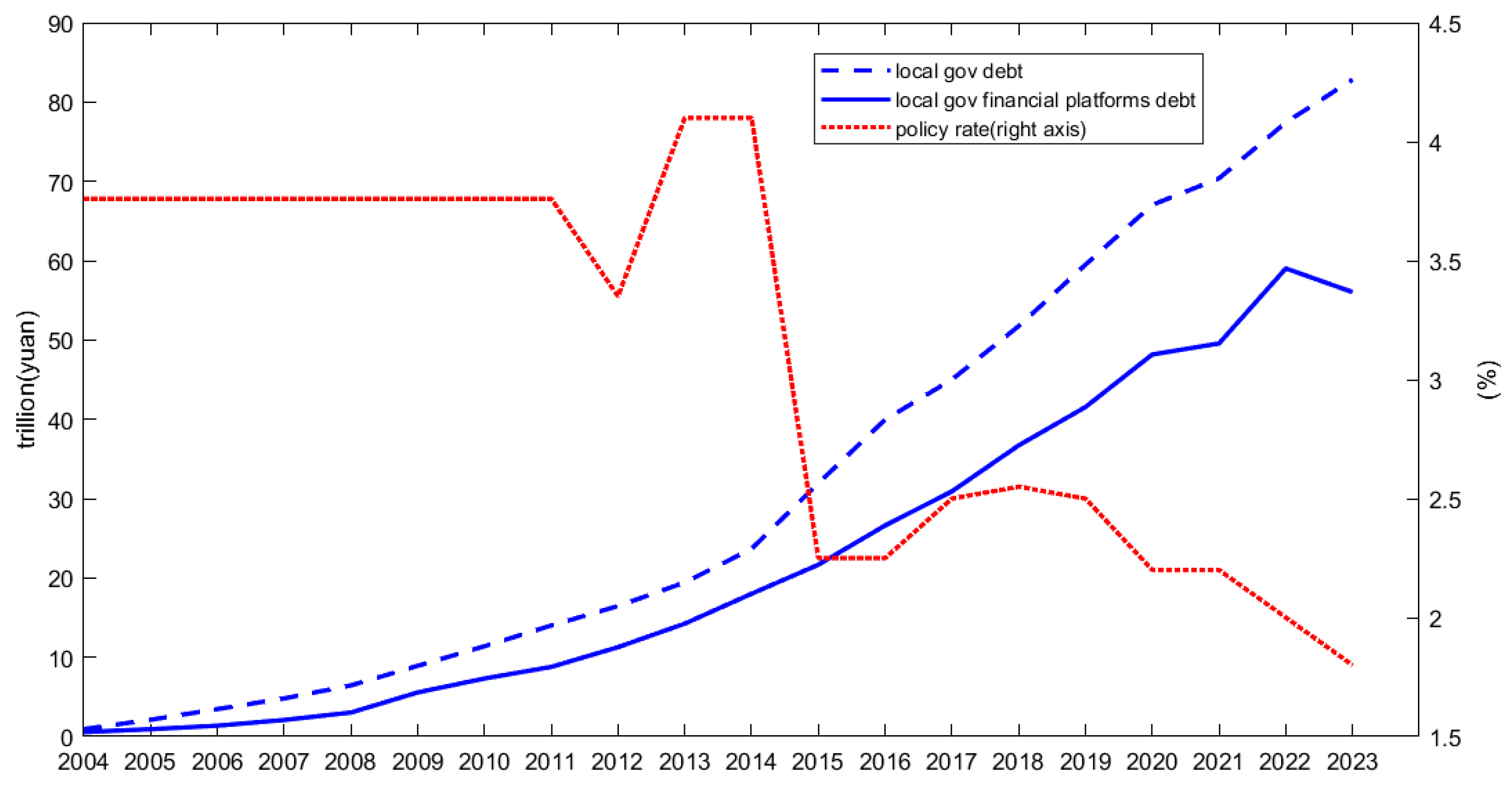

Figure 2.

Another reason is the competition among local governments. This competition has also led to a lack of coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies. While local government competition has been a key driver of China’s economic growth, it has also produced several adverse effects, such as the rapid expansion and regional imbalance of local government debt. These challenges significantly weaken the effectiveness of monetary policy and make coordination with local government fiscal policy difficult [

29]. In response, the central government of China has repeatedly advocated for the accelerated establishment of a unified national market and the enhancement of cooperation among local governments to support the broader domestic economic cycle. Such measures are deemed essential, as competition among local governments has hindered the efficient allocation of market resources.

The escalating levels of local government debt have increasingly drawn scholarly attention to the issue of local fiscal sustainability. The lack of coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies can cause local governments to expand their spending, thereby accelerating the accumulation of local government debt and undermining local fiscal sustainability. Next, we will explain the definition of local fiscal sustainability used in this paper. Buiter et al. [

30] were the first to formally define fiscal sustainability, which primarily refers to a state of survival or the capacity of national finance to support itself. The extant literature presents two predominant interpretations of fiscal sustainability. The first equates fiscal sustainability with fiscal balance, implying that government revenues in any future period are adequate to cover public expenditures [

31]. Second, fiscal sustainability means that government debt financing can be obtained to pay off the old debt [

32] or that it can pay off maturing debt without defaulting on the original debt [

33]. This paper adopts the latter definition, conceptualizing local fiscal sustainability as the capacity of local governments to issue new debt to repay existing obligations or to avoid default. On one hand, local economic growth has slowed, and local government revenue growth has been subdued, partly due to ineffective transmission of monetary policy. On the other hand, proactive fiscal policies implemented by local governments have led to increased rigidity in local fiscal expenditures, thereby exacerbating the debt burden. Consequently, the increased pressure on debt servicing for local governments has constrained local fiscal sustainability.

Current research on the factors affecting the local fiscal sustainability in China mainly focuses on the fiscal and taxation system, intergovernmental relations, demographic aging, and tax reduction policies. Fiscal decentralization, as noted by Li & Wang [

34], can enhance local fiscal sustainability by enabling local governments to leverage their geographic proximity to better comprehend the preferences and needs of their constituents. This approach facilitates enhanced efficiency in the provision of public goods and services, thereby reinforcing local fiscal sustainability. Conversely, fiscal decentralization, according to Li & Du [

26], can negatively impact fiscal sustainability. They highlight that local governments, motivated by promotion incentives, frequently engage in excessive investment and expenditure expansion. Moreover, the authors suggest that augmenting local tax revenue sharing and fiscal autonomy could intensify these challenges by promoting tax competition and further expenditure growth, ultimately exacerbating fiscal deficits. From a demographic perspective, Liu & Zhao [

35] examine local fiscal sustainability from the viewpoint of population aging. This phenomenon not only leads to a contraction in consumer demand and a decline in labor supply but also exacerbates the burden of social security, thereby threatening local fiscal sustainability. Liu & Zhang [

36] examine the effect of tax reduction policies on fiscal sustainability. The results show that tax reductions undermine local fiscal sustainability through two main channels: by distorting local government behavior and by stimulating firm production.

The aforementioned studies ignore the aspect of policy coordination, particularly the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies, which has significant implications for local fiscal sustainability. This issue constitutes the primary focus of the present paper.

Based on the background provided, the primary research questions addressed in this study concern the extent to which monetary policy and local government fiscal policy are coordinated, along with the impact of such coordination on local fiscal sustainability. To investigate these issues, this paper offers both empirical and theoretical analyses of the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies, as well as the consequent implications for local fiscal sustainability, with a particular focus on the Chinese context.

First, the empirical analysis is conducted using regression and an instrumental variable vector auto-regression model (Proxy SVAR). The results indicate that there is coordination between monetary policy and local government fiscal policy in China; however, this coordination undermines local fiscal sustainability in the long term.

Second, building upon empirical analysis, this study develops a two-region dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model encompassing the central government, local governments, financial institutions, households, and firms. The model aim is to analyze the coordinated relationship between monetary and local government fiscal policies, as well as their impact on local fiscal sustainability. It incorporates several key characteristics that are important to China’s economy: (1) the existence of multiple tiers of government, wherein fiscal policies at both central and local levels concurrently influence economic outcomes; (2) the predominant reliance of local governments on investment to drive regional economic growth, with local authorities acting optimally according to inherent incentives; (3) competition among local governments; (4) financial decentralization that fosters competition among local governments over financial resources, resulting in cross-regional financial resource flows; and (5) local financial friction that cause borrowing costs for local governments to deviate from the risk-free rate, generating an excess spread. Findings from the benchmark model indicate that while monetary and local fiscal policies in China are coordinated, such coordination contributes to the accumulation of local government debt, thereby compromising long-term local fiscal sustainability.

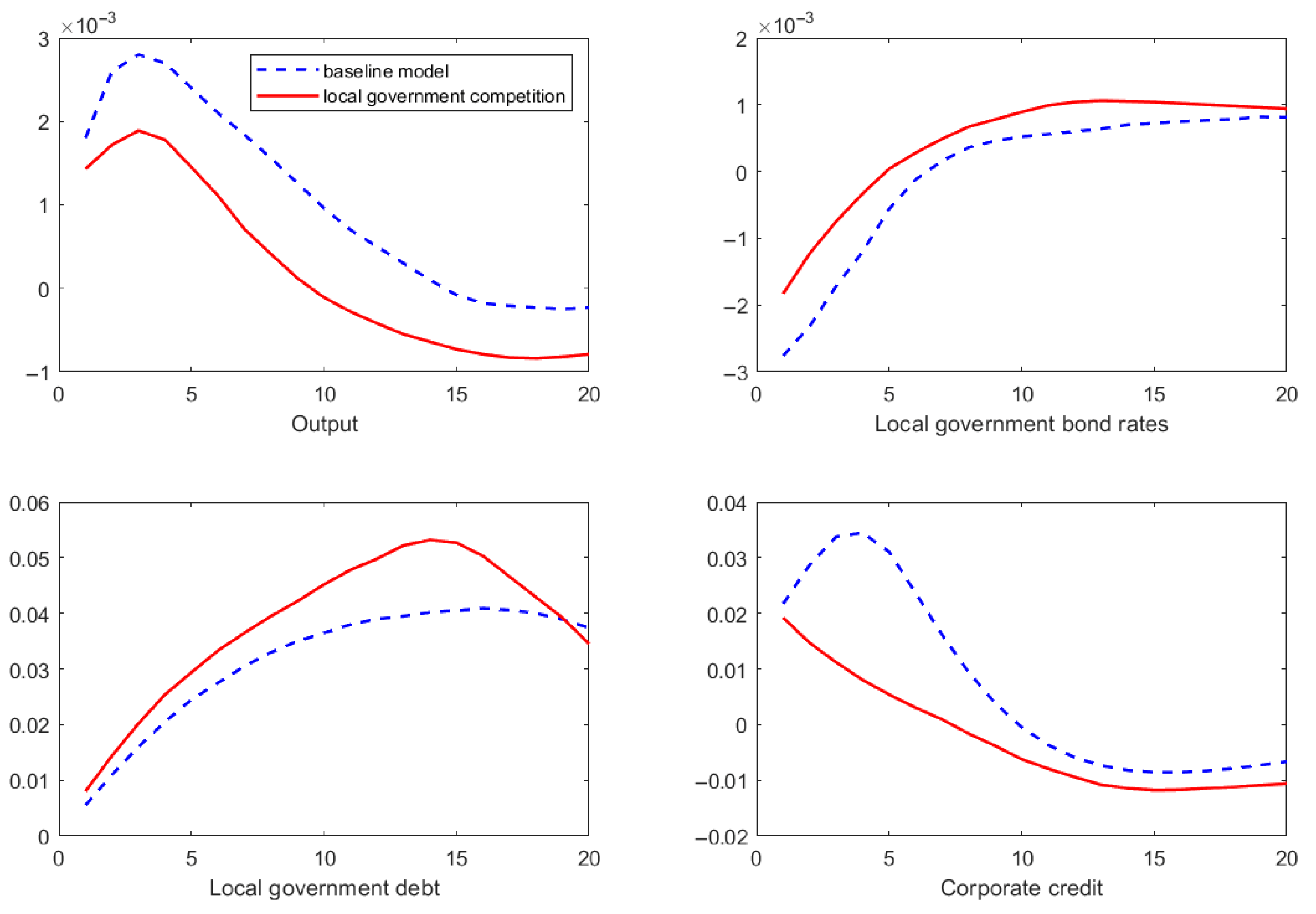

Third, by extending the benchmark model to include factors such as competition and cooperation among local governments, the analysis reveals that competition among local governments leads to a lack of coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies, thereby exacerbating risks to local fiscal sustainability. Conversely, local government cooperation fosters a more coordinated relationship between monetary and local government fiscal policies, which in turn enhances local fiscal sustainability. Moreover, this study further investigates the impact of local government heterogeneity—specifically, variations in steady-state debt levels—alongside local government debt constraints and local financial friction on the coordination of monetary and local fiscal policies, within the context of China’s economic environment. The findings indicate that higher steady-state debt levels for local governments contribute to improved coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies, as well as enhanced local fiscal sustainability. Conversely, debt limits for local governments weaken the coordination between these policies and undermine local fiscal sustainability. Furthermore, monetary policy and local government fiscal policy are better coordinated in the absence of local financial friction, although this ultimately jeopardizes local fiscal sustainability.

The potential contributions of this paper, relative to the existing body of literature, are threefold: (1) It is the first to examine the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies in China, thereby expanding the scope of research on this topic by extending policy coordination from the central level to between the central government and local governments. (2) It investigates local fiscal sustainability from the new perspective of policy coordination, which broadens the research horizon of local fiscal sustainability. (3) It finds that monetary policy exerts influence on the local economy through the local government bond market, which provides an additional economic stimulus beyond traditional channels and enriches the research related to the transmission channels of monetary policy within the Chinese context.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the empirical analysis, while

Section 3 outlines the model setup.

Section 4 details the parameter calibration and the simulation results of the model. Finally,

Section 5 provides the concluding remarks and introduces policy recommendations.

2. Empirical Analysis

Against the background of the current high levels of local government debt and the tax-sharing system, the implementation of local government fiscal policy is markedly shaped by monetary policy. On one hand, when local government debt is huge, monetary policy affects the borrowing costs for local governments, which in turn impacts their fiscal policy and incentives. On the other hand, under the tax-sharing system, local governments frequently encounter significant fiscal deficits, necessitating reliance on debt financing to fulfill their financial obligations. This reliance on debt exacerbates the debt burden faced by local governments, and monetary policy plays a crucial role in shaping their fiscal decision making and implementation. Effective coordination between monetary policy and local fiscal management is achieved when monetary policy enhances the efficacy of local government fiscal policies.

This section conducts an empirical investigation into the coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policy. In particular, it posits that an accommodative monetary policy can reduce bond yields for local governments, thereby lowering their borrowing costs and incentivizing increased investment expenditure and bond issuance—key components of fiscal policy—which collectively promote local economic growth Additionally, the analysis examines how the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies impacts local fiscal sustainability. This section is structured into four parts: (1) a comprehensive overview of the local government bond market; (2) the identification strategy employed to capture monetary policy surprises; (3) a micro-level empirical analysis of the coordination of monetary policy and local government fiscal policy, which includes the effects of monetary policy surprises on local government bond yields and credit spreads, the effect of local government bond yields on fiscal policy, and the interaction effects of local government competition; (4) a macro-level empirical analysis of the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies, utilizing proxy structural vector autoregression (Proxy SVAR) analysis to evaluate the effects of monetary policy surprises. The analysis was conducted using Stata15 and Matlab2024a.

2.1. China’s Local Government Bond Market

Since 2009, China has permitted the public issuance of local government bonds, thereby overturning previous prohibitions. As a result, the principal financing mechanism for local governments has gradually shifted from loans obtained through Chengtou financing platform firms to the issuance of local government bonds. Chengtou financing platform companies, also known as urban construction and investment companies, are state-owned enterprises established by local governments for the purpose of urban construction. These entities serve as a critical instrument through which local governments conduct financing activities and implement urban construction projects.

Although regulations established at the end of the 20th century explicitly prohibited local governments and their agencies from serving as guarantors or borrowers, they did not explicitly forbid local governments from indirectly incurring debt through Chengtou financial platform entities. In response to the abrupt onset of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the central government issued special treasury bonds and subsequently distributed them to local governments to meet the demand for funding local economic development. Meanwhile, local governments established financial platform firms, whose primary funding methods include bond issuance and bank loans, to circumvent the restrictions imposed by the Budget Law on debt.

With the ongoing advancement of industrialization and urbanization, there has been a substantial increase in the number of financing platform enterprises. These firms typically employ diversified financing methods, which include utilizing the fiscal budget or special funds and government revenues as sources of debt servicing, as well as obtaining policy loans through “bank–government cooperation” and “bundled loans”. In response to the global financial crisis of 2008, the central government launched a CNY 4 trillion investment initiative, with local governments accountable for CNY 2.82 trillion of this amount. Consequently, financing platform companies were further developed and eventually became an important tool for financing and investment for local governments.

Beyond financing platform enterprises, local government bonds have emerged as the principal mechanism through which local governments address their funding requirements. Under the “Measures for Budget Management of Local Government Bonds,” promulgated by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) on 18 February 2009, certain local governments were authorized to borrow funds directly. This document outlines how the Ministry of Finance began issuing government bonds on behalf of local governments at the provincial level, incorporating them into local governments’ fiscal budgets and establishing their debt. Local governments continued to issue bonds worth CNY 200 billion annually between 2009 and 2011. In 2011, the central government permitted Shanghai, Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Shenzhen (as selected planned single-listed cities, which have greater autonomy regarding economic management and are equivalent to provinces in economic affairs) to issue bonds on a trial basis within the allowable quota. Subsequently, in 2013, the central government approved the inclusion of Jiangsu and Shandong as trial areas. The Ministry of Finance announced the “Local Government Bonds Self-Issuance and Self-Repayment Pilot Measures” on 22 May 2014, and Beijing, Qingdao (a city like Shenzhen), Jiangxi, and Ningxia joined the six pilot provinces to participate in the program. This initiative signifies a shift toward local governments independently issuing bonds and assuming full responsibility for the repayment of both principal and interest.

The issuance volume of local government bonds increased to CNY 250 billion in 2012, CNY 350 billion in 2013, and CNY 400 billion in 2014. By 1 January 2015, the revised Budget Law clarified that local governments must raise debt under budgetary constraints and lifted the legal restrictions on bond issuance. Since 2015, the scale of local government bonds has been gradually increasing, and it has become the main way for local governments to raise funds. Currently, the majority of local government debt comprises both budgeted liabilities and off-budget hidden debts, predominantly represented by bonds issued by financing platform firms, commonly referred to as Chengtou bonds. Bonds issued by financing platform firms are regarded as a unique type of local government bonds, as these companies are primarily established to undertake functions related to local government. According to the announcement by the Ministry of Finance, by the end of December 2024, the total outstanding local government bonds amounted to CNY 47.54 trillion, while the bonds issued by Chengtou financing platform firms reached CNY 15.52 trillion. In 2024, local governments repaid CNY 2.99 trillion in principal and CNY 1.35 trillion in interest.

Monetary policy and local government fiscal policy can be effectively coordinated through the development of the local government bond market. Monetary policy influences local government bond yields and credit spreads, which subsequently impact local government behavior and incentives. This, in turn, affects local economic development and fiscal sustainability.

2.2. Identification Strategy for Monetary Policy Surprises

The identification of monetary policy surprises facilitates subsequent micro and macro empirical analyses, particularly when these shocks serve as proxy variables for central bank monetary policy actions. This study employs high-frequency identification techniques to detect monetary policy surprises, specifically leveraging financial market transaction data. By utilizing daily or intraday trading data, the high-frequency identification approach isolates exogenous monetary policy shocks. This methodology provides enhanced informational content derived from financial market transactions and more robustly addresses the challenge of causal identification, especially amid concurrent fluctuations in economic and financial variables [

37].

The high-frequency identification approach utilizes price variations in financial markets occurring within a relatively short interval (e.g., 30 min) during the trading day to detect monetary policy surprises [

38]. Price fluctuations in financial markets are primarily independent of other events and can be ascribed to the influence of monetary policy changes because there are virtually no other significant events taking place during the short time window. There is no appropriate intraday price window in China because the majority of China’s monetary policy announcements, including reserve ratio and benchmark interest rate changes, are made during the hours when most financial markets are not trading. For this reason, this paper uses the daytime window to compute price changes in financial markets.

In this paper, we construct a series of exogenous shocks to China’s monetary policy using the daily price series of 1-year interest rate swaps based on the 7-day interbank repo fixing rate (FR007-IRS). The impact of monetary policy adjustments on FR007 is both direct and timely. Additionally, the 1-year FR007-IRS in China is actively traded and widely marketed, making it an appropriate base price indicator for the series of exogenous shocks related to China’s monetary policy [

39]. The data period covers January 2009 to December 2023.

The methodology for calculating monetary policy surprises is defined as follows: If the policy announcement occurs when the market opens on a business day, the difference between the closing price on the day of the announcement and the closing price on the previous business day will be used. If the policy announcement occurs after the market closes on a business day, the difference between the closing price on the day of the announcement and the closing price on the day following the announcement will be used. If the policy announcement is made during a weekend or holiday, the difference between the closing price on the first business day after the announcement and the closing price on the last business day before the announcement will be calculated.

In this paper, China’s monetary policy announcements are defined as the concatenation of the following three types of announcements: changes to the legal reserve ratio, adjustments to the benchmark lending rate, and quarterly reports on the implementation of monetary policy. The correlation coefficients of this raw monetary policy shock series with the reserve ratio and the benchmark lending rate are −0.67 and −0.75, respectively. These findings suggest that the raw series derived through the high-frequency identification approach accurately captures the directional changes in monetary policy.

2.3. Regression Analysis

2.3.1. Monetary Policy Surprises and Local Government Borrowing Costs

Using Equation (1), we estimate the effects of monetary policy surprises on the yields and credit spreads of local government bonds and corporate bonds:

where

is the monetary policy shock,

represents the day-to-day change in maturity yields and credit spreads of the underlying assets (local government bonds, Chengtou financing platform firm bonds, and corporate bonds) around the date of the central bank’s monetary policy announcement. For every percentage point of monetary policy shock, the coefficient

indicates the percentage point change in the yield to maturity of corporate or local government bonds.

Table 1 demonstrates that the coefficient estimates for yields and credit spreads are significantly positive across all asset classes. This indicates that accommodative monetary policy results in a decline in both the yields and credit spreads of the underlying bonds. Notably, local government bonds exhibit the smallest magnitude of response, whereas corporate bonds demonstrate the most pronounced reaction. The yields of Chengtou bonds fall in the middle, aligning with the findings of Kamber & Mohanty [

39]. Regarding credit spreads, which indicate the risk associated with the underlying bond assets, the above coefficients suggest that accommodative monetary policy mitigates the risk of these bonds, consistent with the findings of related studies in the literature.

The response of corporate bonds to monetary policy surprises is significant, as it is nearly twice as high as the response of Chengtou and local government bonds to monetary policy surprises. This suggests that the response of Chengtou and local government bonds is dampened, most likely due to the greater financial friction encountered by Chengtou financing platform firms and local governments. Consequently, if this dampened response is not accounted for in model design, the results may overestimate the impact of monetary policy on local government fiscal policy. We will incorporate this dampened response into the model construction below.

2.3.2. Monetary Policy Surprises and Local Government Behavior

In order to utilize more information from the data, the following regressions focus on the yield to maturity of municipal bonds. Following the work of Adelino et al. [

40], we employ Equation (2) to further investigate the impact of local government borrowing costs (yields) on local government behavior (fiscal policy):

where

indicates the investment expenditure of local governments or the scale of debt issuance,

is the annual average of the yield to maturity of local government bonds, and here, the annual summation of monetary policy shocks is used as its instrumental variable.

includes the GDP of local governments, fiscal revenues, and yields to maturity of treasury bonds.

Table 2 illustrates that yields on local government bonds exert a significant influence on both the issuance of these bonds and local government investment expenditures. Notably, the effect on bond issuance is more than twice as large as that on investment spending. Specifically, a 1% reduction in local government bond yields corresponds to a 2.32% increase in investment spending and a 4.78% rise in the volume of local government debt issuance. This suggests that local government fiscal policy, encompassing both investment spending and the size of debt issuance, is strongly influenced by borrowing costs, which in turn have a substantial effect on local government fiscal behavior.

The regression results support that monetary policy can influence local government fiscal policy through its effect on costs. Simultaneously, increased local government investment and debt levels have been shown to promote the local economy [

41]. This channel has become an important conduit for the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies. Consequently, monetary policy can enhance the efficacy of local government fiscal policy and thus facilitating the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies. Nevertheless, the accumulation of debt by local governments, driven by efforts to stimulate economic development, imposes greater debt servicing burdens, which may ultimately compromise local fiscal sustainability.

2.3.3. Interaction of Local Government Competition

Specific information about local government will affect local fiscal behavior in response to borrowing costs. According to the developmental history of local economy, local economic development comes largely from the advancement of industrialization and urbanization. Local government competition is an important driving force for local economic development, and it also influences how the local government reacts to macroeconomic policies. To learn more about how local government competition affects how local governments react to borrowing costs, Equation (3) is estimated:

where

denotes province-specific information that affects the response of local government bonds to monetary policy surprises, here referred to as local government competition. Following the work of Miao et al. [

42] and Chen et al. [

43], a local government competition indicator is constructed. Under the economic efficiency-oriented appraisal system, local governments tend to view neighboring regions and economically developed regions as crucial competitive controls and actively attract liquid production factors by implementing a series of strategic competitive means, with a view of realizing rapid catch-up development of the economy, followed by narrowing the development gap between these benchmark regions. The local government competition indicator not only takes into account the economic development of local governments in comparison with neighboring provinces, but also places it in the national context so that it can comprehensively and objectively reflect the intensity of local government competition in each region. Its specific calculations are as follows:

When the coefficient of local government competition is large, local economic development comparatively lags behind, and competition is needed to narrow the gap with other regions; on the other hand, when the coefficient of local government competition is small, it means that the local economic development is better, the gap between the reference region is smaller, and the pressure of competition is relatively low.

As illustrated in

Table 3, the interaction term between the yield on local government bonds and local government competition exhibits a significantly positive coefficient in relation to local government investment expenditure. Conversely, this interaction term demonstrates a significantly negative coefficient concerning the scale of local government debt issuance. This indicates that the more fiercely local government competition exists, the less local government investment expenditure responds to borrowing costs, and the more the scale of debt issuance responds to borrowing costs. The above regression results indicate that local government competition not only weakens the ability of monetary policy to enhance the effect of local government fiscal policy through local government borrowing costs, thus hindering the coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies, but also leads to the accumulation of more local government debt, which further threatens the local fiscal sustainability. This is consistent with the reality in China. Competition among local governments has led to excessive spending and a significant increase in bond issuance, resulting in competition for financial resources. As a result, local government investment has decreased, and the stimulus effect of monetary policy has been weakened due to higher financing costs.

2.4. Proxy SVAR Analysis

Beyond the regression analysis conducted on micro-level data, we additionally employ vector autoregression (VAR) analysis utilizing macro-level data. Given the sensitivity of conventional structural VAR (SVAR) models to identification assumptions, we adopt the Proxy SVAR approach as proposed by Gertler and Karadi [

38] and Chen et al. [

37]. This method leverages external instrumental variables to examine the coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies, as well as their effects on local fiscal sustainability.

The Proxy SVAR model’s primary characteristic is its dependence on information from external systems to detect structural shocks in endogenous economic variables. In order to do this, the external instrumental variables must be unrelated to structural shocks in other variables but correlated with the discovered structural shocks. The primary advantage of this identification mechanism is that it overcomes issues of endogeneity caused by measurement errors in economic variables and contemporaneous correlations, thereby providing a more accurate assessment of the causal effects of structural shocks on the macroeconomic system. Furthermore, the number of observations is not limited by the sample size of endogenous variables under this identification process, and external instrumental variables can be produced in a variety of ways. According to Gertler & Karadi [

38], they may consist of high-frequency data sequences derived from financial markets, shock sequences replicated by dynamic–static equilibrium models, and descriptive time series. The previously described identification of monetary policy surprises in China offers a solid instrumental variable for the Proxy SVAR analysis here, despite the fact that appropriate instrumental variables are hard to find.

The data interval is from January 2009 to December 2023. We seasonally adjust the relevant data, which are obtained from the Wind database. We first consider the following lagged P-order VAR model:

where endogenous variables

include monetary policy instruments (R007), abbreviated as MP; local government fiscal policy variables (year-on-year growth rate of industrial value added, abbreviated as IP, year-on-year growth rate of commodity housing sales pricing, abbreviated as HP, and local government debt size, abbreviated as DB); CPI inflation, and credit spreads on Chengtou bonds, abbreviated as CS. In order to maintain sufficient degrees of freedom in the vector autoregressive model, this paper draws on the methodology of Ramey [

44] and adopts the practice of substituting one variable at a time in the model to examine the substituted variable’s impulse response. To control for external shocks, exogenous variables

are added to the VAR, including the VIX index; the commodity price index, abbreviated as CP; and the one-year U.S. Treasury yield, abbreviated as US. High-frequency policy surprises are converted to monthly frequencies by summing the daily changes in the price of 1-year interest rate swaps of the 7-day interbank repo fixing rate. Under the dual-wheel-driven development model of industrialization and urbanization, the data pertaining to industrial value-added and housing prices might reflect the behavioral logic of the local government.

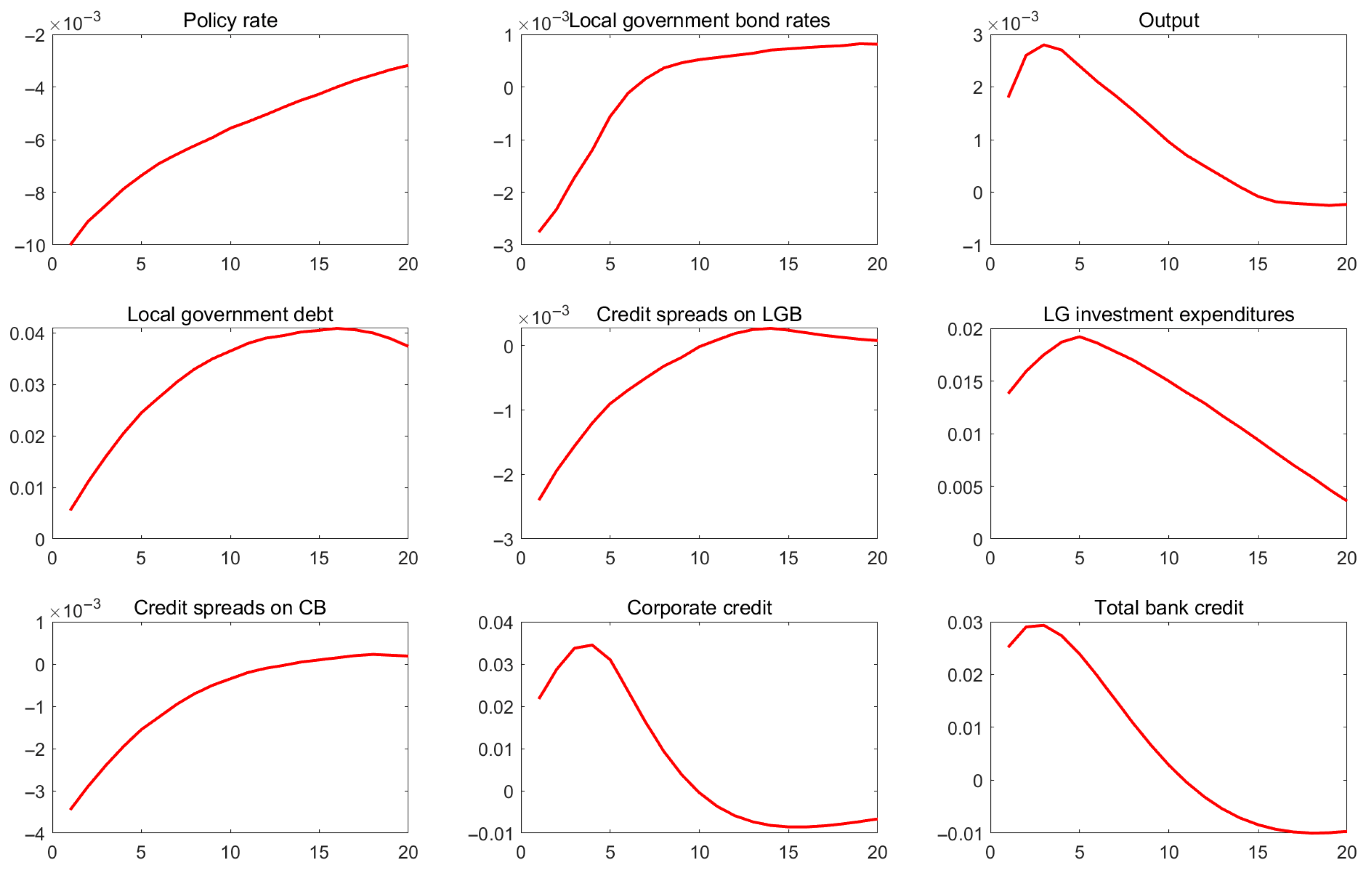

Figure 3 presents the impulse response to a monetary policy easing shock. The figure demonstrates that such a shock reduces local government borrowing costs, which subsequently leads to an increase in the year-on-year growth rates of both industrial value added and commodity housing sales prices. Concurrently, it results in heightened local government indebtedness, thereby posing potential risks to local fiscal sustainability. In particular, when the interest rate falls by 1%, it leads to a decline in local government borrowing costs that lasts for a few months, before rising a few months later. Simultaneously, the positive response in the size of local government debt is larger and more persistent. In contrast, the rise in year-on-year industrial value added growth is more persistent and enters the negative space only after the 18th period. The persistence of the rise in the year-on-year growth rate of commercial property sales prices is relatively weak, lasting only seven periods. Overall, this VAR impulse response provides further empirical evidence on the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies in China and its impact on the local fiscal sustainability. It also serves as a stronger point of reference for the model building and analysis that follows.

2.5. Summary of the Empirical Analysis

The impact of monetary policy shocks on the yields of local government bond is first empirically examined in this section using micro data. The average response of yields on local government bonds to a monetary policy shock of 1% is 0.24%, which is a dampened response that is less pronounced than the response of corporate bonds. The empirical analysis of borrowing costs and local government behavior further confirms the existence of coordination between monetary policy and local government fiscal policy in China, which weakens local fiscal sustainability. Local government competition not only hinders the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies in China, but also further undermines local fiscal sustainability. The impulse response analysis of the Proxy SVAR model shows that monetary policy shocks can improve the effect of local government fiscal policies by lowering local government borrowing costs, thus realizing the coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies. Both regression and VAR analyses suggest that the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies occurs in China, and that such coordination poses some threat to long-term local fiscal sustainability. These empirical results provide a realistic basis for the model construction and quantitative analysis below.

3. Theoretical Model Setup

In this section, we examine how monetary policy and local government fiscal policy are coordinated and how this affects local fiscal sustainability using a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model. The analysis is mainly conducted through the impulse response of monetary policy shocks. The research methods used in this paper are as follows: (1) extracting macroeconomic information using the DSGE model; (2) calibrating the specified parameter values, and (3) examining the effects of monetary policy in various scenarios.

Based on the empirical findings presented in the previous section, this section develops a two-region open economy model that incorporates some typical characteristics of China’s economy to examine the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies and its impact on the local fiscal sustainability. The model differentiates between fiscal policies implemented by local and central governments. The central government collects tax revenues through a tax-sharing mechanism, which it subsequently allocates as transfers to local governments. The central bank chooses the risk-free rate. Each region includes the productive sector, households, banks, and local government. A key distinction of this model relative to existing frameworks in the literature lies in the representation of the local government sector. Notably, this model incorporates the empirically observed attenuated responsiveness of local government borrowing costs to monetary policy shocks, a feature that influences the transmission dynamics of monetary policy shocks within the local economy.

The productive sector produces heterogeneous intermediate goods and packages the intermediate goods into final goods for consumption by households and the central government in the two regions and for investment by the producers of investment goods, while the local government uses only locally produced goods for consumption and investment. Households in each region consume, save, and provide labor. Financial institutions in each region purchase corporate and local government bonds in both regions and receive deposits from households. Local governments are financed by corporate tax revenues, bond issues, and central government transfers, which are used for local government consumption and investment.

The interest rate on local government bonds is set independently of the interest rate on household savings, which introduces the previously claimed dampened response of local government borrowing costs to monetary policy shocks. Local government borrowing costs depend on the risk-free rate, the deviation of debt from steady state, and the parameters of the relationship between monetary policy shocks and the interest rate actually paid by local governments (coefficient in the previous regression). Local governments in China are investment-driven, and their primary role is to stimulate local economic development through public investment, in contrast to the role of local (state) governments in typical market economies. Additionally, there is a policy game between local governments in the two regions which introduces local government competition.

3.1. Household

Following Bi & Traum [

45], The household sector is set using the following formula. Representative households maximize expected intertemporal utility as follows:

where

is composite consumption;

is the number of hours worked. Each househols displays consumption habits, and its real budget constraint is

where

represents real wages. Households make one-year savings deposits with financial intermediaries.

denotes the amount of the household’s savings deposit,

denotes the total nominal interest rate on deposits between period

t − 1 and period

t, which has been set in period

t − 1.

is a nominal single-tranche bond traded between two districts at the deposit rate common to all districts, which is the same as the rate set by the central bank. In addition, households receive profits

from firm ownership and dividends

from financial intermediaries. Households make fixed transfers to the new financial intermediary during each period, represented by

x. We define

.

The composite consumption

aggregates the consumption sub-baskets for regions 1 and 2,

and

:

where the parameter

represents the elasticity of substitution between regional goods, and

is the relative preference of households for region 1 goods. Let

and

denote the real prices of region 1 and region 2 commodities measured in region 1 consumption units, respectively. The aggregate price index is

The sub-baskets

aggregates the differentiated consumption varieties

in region 1, and

aggregates the differentiated consumption varieties

in region 2, given by the following equation:

where

is the elasticity of substitution between goods within regions.

3.2. Production

Following the work of Sims & Wu [

46] and Gertler & Karadi [

47], this model contains three different types of firms. The representative wholesale firm issues bonds to finance capital purchases and uses its own capital and labor to produce goods. While representative investment goods generating enterprises create new investment goods utilizing final products, retail firms repackage wholesale commodities for resale and are subject to price stickiness.

Investment Goods Firms. Competitive investment goods-producing firms use final goods to produce new investment goods and sell them to wholesale firms at price . The investment goods-producing firms use commodities from regions 1 and 2 (in the same Armington form as the consumer goods aggregates) to obtain a composite investment good , which in turn is used to produce new capital .

The new investment goods production function is

where

is the investment adjustment cost function. Therefore, the firm’s optimization problem is given by the following equation:

Wholesale Firms. A representative wholesale company produces output according to the following formula:

where

is exogenous productivity.

denotes the public capital provided by the local government.

is the output elasticity with respect to public capital, which determines the productivity of public capital.

is private capital owned by wholesale firms and evolves according to the standard law of motion:

Following the methods of Sims & Wu [

46], we assume that the wholesale firm faces an advance loan constraint and must issue perpetual bonds to finance a small portion of the new physical capital. The advance loan constraint is expressed as follows:

where

represents the number of corporate bonds. Wholesale firms make decisions about labor, investment, and bond issuance to maximize the present value of their profits,

subject to the production Function (13), the capital accumulation Equation (14), and the advance loan constraint (15).

Retail firms. The retail firm

h repackages the wholesale product,

, and sells it at price

. The firm faces a Rotemberg price adjustment cost, and the cost function can be expressed by

The retail firm

h chooses its price to optimize real profit, given by the following equation:

After realizing equilibrium, optimal price setting implies

3.3. Financial Intermediaries

There is a continuum of financial intermediaries on the interval, much like that suggested by Sims & Wu [

46] and Bi & Traum [

45]. The equal number of new intermediaries that receive start-up funding from households replace the small percentage of intermediaries that randomly leave during each period. Net worth is returned to households by financial intermediaries, who build up net worth until they leave.

Financial intermediary

j can purchase local government bonds

and corporate bonds

in its region or from region 2,

and

, respectively, and its purchases are financed by household deposits

and net worth

in its region, with the real balance sheet given by the following equation:

The equation to obtain the evolution of the net worth of the financial intermediary

j is

where

,

,

, and

, respectively, are the excess returns of financial intermediaries in region 1 holding local government bonds, as well as corporate bonds, compared to deposit rates. The return on holding corporate bonds is

Each period, a fraction of

of financial intermediaries randomly exit and return their net worth to the household owner, and the financial intermediary

j maximizes its lifetime discounted net worth, as follows:

An intermediary will desire to increase its assets indefinitely by accepting household deposits, if investing in municipal bonds may yield positive excess returns. In order to restrict their capacity to do so, we presume that financial intermediaries encounter a CSV issue, as shown in the work of Gertler & Karadi [

47]: at the end of a period, the intermediary can transfer a portion of its assets and pass them on to the household owner, in which case the depositor can reclaim the remaining assets and force the intermediary to go bankrupt. Following Krenz [

48], the incentive constraint is a CES combination of region 1 and region 2 assets:

where

The parameters and denote the interest rate elasticity of demand for assets, and denote the local bias of asset holdings. The incentive constraint’s assumption of imperfect substitution between region 1 and region 2 assets can represent the varying asset-type preferences of financial intermediaries, their different views on cross-region asset risk, and the convenience gains brought about by inter-region regime changes. The incentive constraint implies that if a financial intermediary chooses to go bankrupt, it can retain a portion of its corporate bond portfolio, as well as a portion of its local government bond portfolio. The assumption that 1 suggests that corporate bonds can be transferred more easily via financial intermediaries than bonds issued by local governments. The above condition implies that the value of continuing to act as an intermediary should be greater than or equal to the amount of money that the financial intermediary can transfer. The parameter reflects the tightness of the credit market: the higher parameter , the more money the financial intermediary can transfers, and the fewer number of willing savers required to lend money.

Finally, we assume that new entrant intermediaries receive start-up capital from households, which is denoted by

x. The equation to obtain the change in total net worth of the financial institutions sector is

Assuming that all financial intermediaries makes the same best choices, the financial intermediary sector’s balance sheet is

3.4. Local Governments

Following the work of Ai & Wang [

49] and Wilson [

50], we assume that government consumption and investment are fully biased in favor of intra-regional goods, so that they now buy local goods at the price

. In order to pay for its public spending, the local government issues bonds, receives transfers from the federal government, and collects business taxes. The following formula provides its actual financial constraint:

where

denotes local government public investment, and

denotes local government public consumption. The public consumption expenditure of the local government is exogenously given as

, where

denotes the total steady-state expenditure of the local government, and

is the ratio of public consumption expenditure of the local government to the total expenditure.

represents the local government tax revenue share ratio,

is the tax revenue,

, and

is the transfer payment from the central government to the local government.

denotes the bonds issued by the local government, and

is the local government bond interest rate; note that the local government bond interest rate is here assumed to be independent of the household savings interest rate, and following the work of Schmitt-Grohe & Uribe [

51], the local government bond interest rate is determined by the following equation:

where the imperfect response of the government bond rate to the risk-free rate is captured by the parameter

, which is the response parameter of local government bond yield to monetary policy shocks, a formulation that has the advantage of allowing for the setting of an arbitrary steady-state level of debt and capturing local financial friction more easily. When

= 0, it indicates that local governments can issue bonds at the risk-free interest rate, suggesting that local governments are not facing local financial friction. The interest rates for bonds issued by local governments through urban investment platforms are even higher than those for corporate bonds issued by listed businesses, indicating that local governments are obviously experiencing financial friction in China. In addition, local government bond interest rates are less responsive to monetary policy than those of listed companies, as local governments have close ties with local commercial banks and can obtain funds from banks on a priority basis. As a result, they are less sensitive to monetary policy than are ordinary enterprises.

When local governments issue bonds, it is essential to account for the effects on both current and future borrowing costs, as addressed in the aforementioned framework. The influence of local government bond issuance on borrowing rates is a critical factor that should not be overlooked, as it affects the model’s steady-state equilibrium, as well as the dynamic response of debt to short-term shocks. In the absence of any impact of local government bond levels on borrowing costs, the government would, under typical interest rate conditions, accumulate an unbounded amount of debt. Consequently, failing to incorporate the effect of debt on borrowing costs would lead to a significant underestimation of the market’s response to excessive local government debt.

One significant aspect of China’s economic transition period is the “tournament” style of fiscal expenditure rivalry amongst local governments [

52]. China’s economic development model has been summed up as follows since its reform and opening up: attracting foreign direct investment with competitive fiscal, tax, land, and labor incentives; encouraging the full combination of foreign high-level production factors and local low-cost factors; followed by unleashing massive production capacity and export scale. According to Li [

53], local governments play a significant role in market competition by directly interfering with the distribution of resources. We introduce local government competition in the following equation.

In the work of Ai & Wang [

49], local governments are assumed to choose their own public investment expenditures to maximize their own utility under the constraint of the resulting objective function, which is given by the following equation:

where

denotes that local governments face additional smoothing incentives, and

is taken to be 0 or 1, which indicates whether the local government’s objectives include comparisons with other regions (i.e., whether there is local government competition); governments will also be concerned about fluctuations in the economy, as follows:

where

and

represent the coefficients of government utility in response to bond and output fluctuations. The above equation shows that local governments generate additional negative utility due to rising local government debt levels and economic fluctuations, i.e., the growth motive and the stability motive in local government utility.

This study extends the existing model by incorporating not only local government competition but also local government cooperation. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, China has expedited the transformation and upgrading of its open economy in response to shifts in the external development environment and increasing domestic factor costs. Concurrently, the country has vigorously pursued the restructuring of its economic development model, actively enhanced institutional openness, and proactively engaged in global economic governance [

51].

When local governments cooperate, they focus on both the level of output growth and the level of debt in two whole regions and maximize the utility of both regions by choosing the level of local government investment. The utility function is

Local government’s public investment becomes productive public capital after a time and affects the productivity of firms; the equation of motion of local government public capital is .

In the local government optimization process, all equations (including the relevant equations for households, vendors, financial intermediaries, and the central government) become the constraint equations for local government decision making, and the local governments of the two regions play the game and generate the Nash equilibrium based on the observation of the whole economic operation. For the solution method, see Bodenstein et al. [

13].

3.5. Central Government and Monetary Policy

According to Bi & Traum [

45], a monetary union establishes a common monetary policy for both regions by having the central bank set nominal interest rates across the economy using the Taylor rule:

The monetary authority responds to changes in the average consumer price inflation, and the output-weighted average, .

The central government carries out government expenditures and transfers, and its revenues are derived from the share of tax revenues:

where

denotes central government expenditure. To simplify the analysis, it is assumed that the level of central government expenditure is equally distributed between the two regions.

3.6. Market Clearing

The clearing of the corporate bond market means that

The clearing of the local government bond market means that

The cross-regionally traded bond market clearing is

The product market clearing is

Given that the nominal exchange rate remains unchanged, the condition that the real exchange rate is correlated with relative inflation can be used to characterize the adjustment of regional relative prices:

The net foreign asset equation is expressed as follows:

3.7. General Equilibrium and Dynamic Systems

The general equilibrium of the entire economy is characterized by the following conditions: (1) Given prevailing prices, households maximize their utility, producers maximize their profits, wholesalers determine optimal bond issuance, and financial intermediaries seek to maximize their lifetime discounted net worth. (2) The central government satisfies its budget constraint. (3) Local governments choose investment expenditures under local government budget constraints to maximize local utility. In the process of local government optimization, all relevant equations pertaining to households, firms, and the central government serve as constraints for local governments. Local governments in two regions engage in a game based on observing the overall economic operation to produce a Nash equilibrium outcome. (4) All markets—including the bond market, capital goods market, labor market, final goods market, intermediate goods market, and deposit market—clear. It is important to note that equation sets (5)–(32) and (34)–(44) represent the dynamic system of the entire economy under the benchmark model and in scenarios where local governments compete, whereas equation sets (5)–(30) and (32)–(44) characterize the dynamic system when local governments cooperate.

5. Conclusions and Implications

The coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies, as well as its impact on local fiscal sustainability, is not well covered in the existing literature. This study empirically demonstrates that, in China, monetary policy and local government fiscal policy are indeed coordinated; nevertheless, such coordination adversely affects local fiscal sustainability. Building upon these empirical results, the study further employs a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model—customized to capture the distinctive characteristics of the Chinese economy—to quantitatively assess the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies and their implications for local fiscal sustainability.

The benchmark model indicates that China’s monetary policy and local government fiscal policy are coordinated; however, this coordination permits the accumulation of local government debt, which ultimately undermines long-term local fiscal sustainability. As far as policy effects are concerned, such as boosting local economic growth, policy coordination can be achieved by increasing the efficiency of monetary policy and local fiscal policy to boost local economic growth. However, this economic growth is realized in the form of local government debt expansion, thus undermining local fiscal sustainability in the long run, as local government debt is cumulative. In the short run, the impact of policy coordination on local fiscal sustainability is negligible because of local economic growth. Regarding policy coordination, the findings of this study indicate that coordination among local governments yields mutual benefits, as it not only promotes local economic development but also substantially mitigates the rate of increase in local government debt.

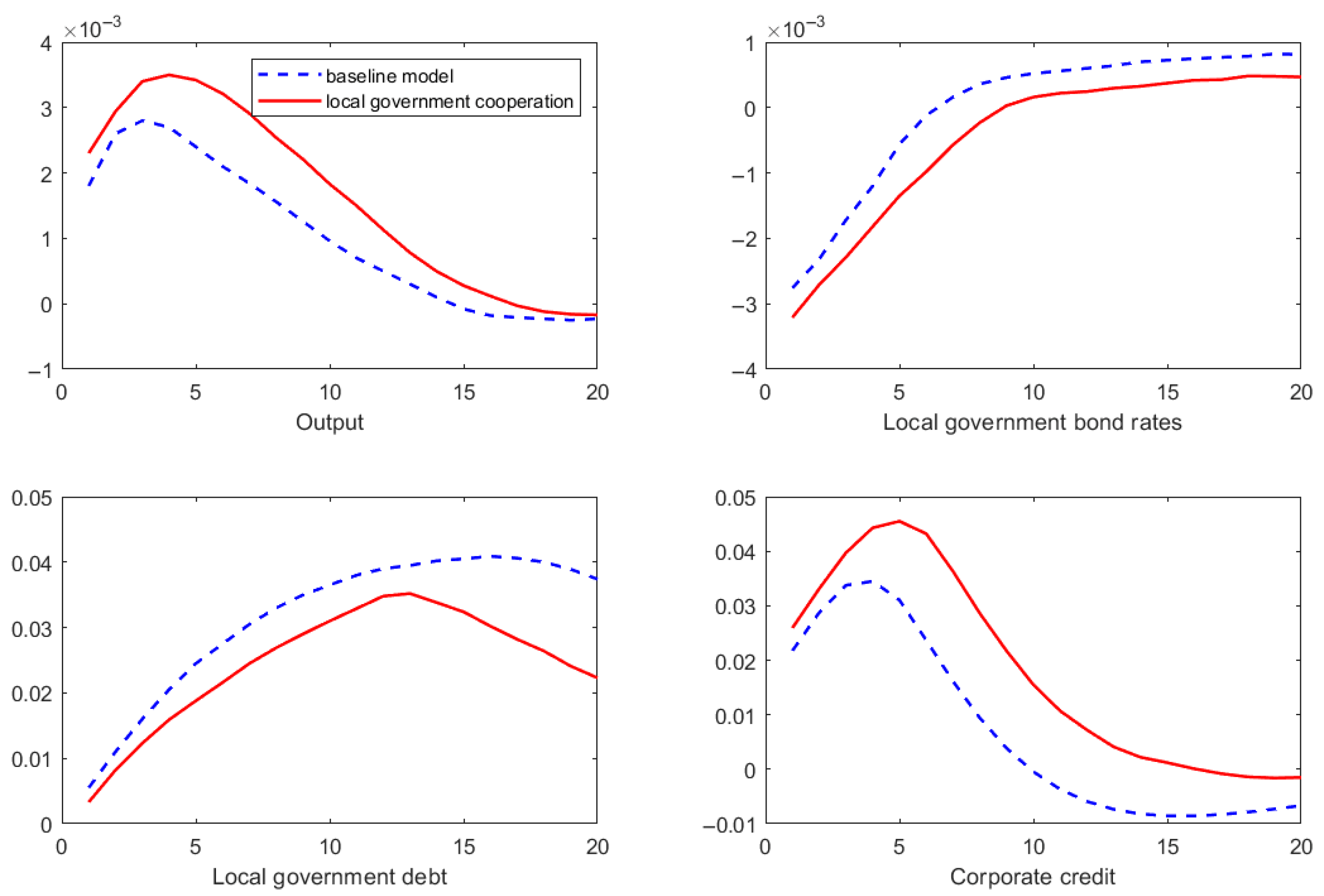

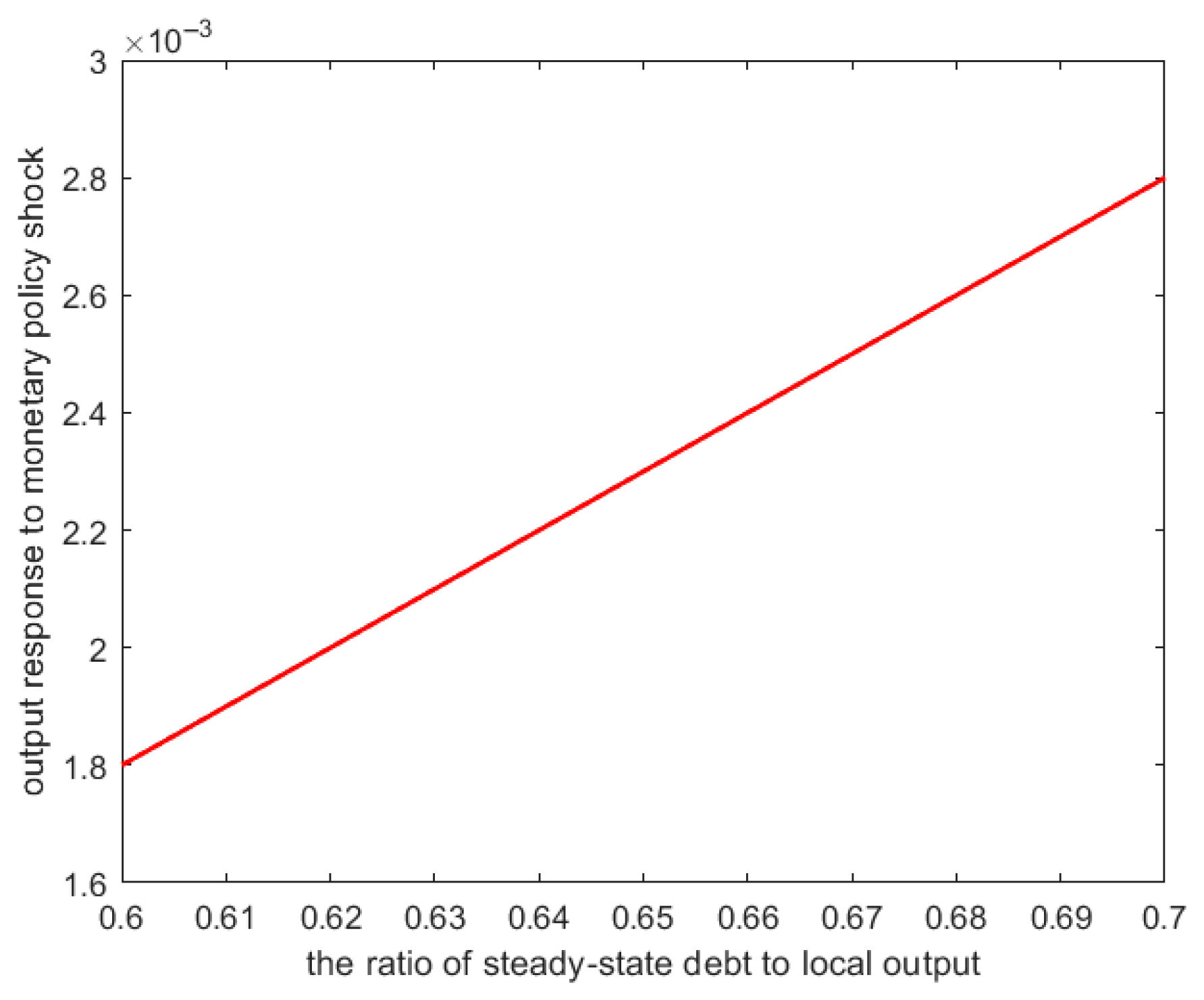

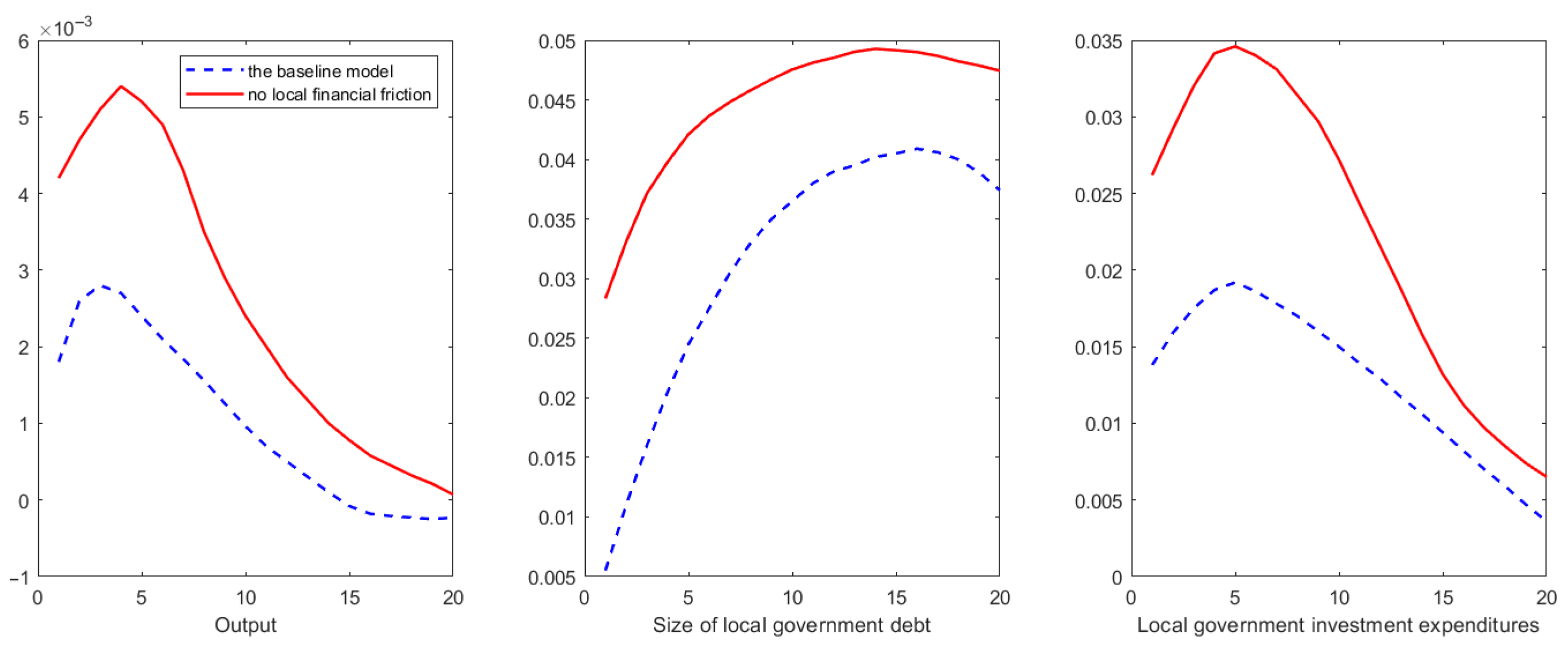

To further elaborate on the benchmark model, the notions of local government cooperation and competition are incorporated. Under conditions of local government competition, monetary policy and local fiscal policy become disconnected, resulting in a more pronounced adverse effect on local fiscal sustainability. Specifically, loose monetary policy shocks result in a slower decline in local government bond rates, a more rapid increase in debt level, and slower growth in corporate credit. These dynamics precipitate crowding-out effects that attenuate the responsiveness of output growth. Conversely, when local governments cooperate, monetary policy and local government fiscal policy are more coordinated, thereby enhancing local fiscal sustainability. Within this cooperative framework, local government bond yields decline more swiftly, debt accumulates at a reduced rate, corporate credit grows more rapidly, and output experiences stronger growth. A higher steady-state level of local government debt is associated with improved coordination between monetary and fiscal policies, which in turn promotes local fiscal sustainability. Under such conditions, increased local government expenditure exerts a more stimulative effect, and fiscal policy becomes more efficacious, ultimately fostering greater local output growth. Conversely, the imposition of debt constraints on local governments impedes the coordination of monetary and fiscal policies and undermines local fiscal sustainability. In the absence of local financial friction, local governments can borrow at risk-free rates, thereby amplifying the stimulative impact of monetary policy on local economic output. While this scenario enhances the coordination between monetary and fiscal policies, it may compromise the sustainability of local fiscal positions in the long term.

This paper presents three key policy insights: (1) The coordination between monetary policy and local government fiscal policy plays a critical role in enhancing the overall efficacy of macroeconomic policy. When monetary policy and local government fiscal policy are coordinated, the effects of both are greatly enhanced. This coordination alleviates the burden of local government debt and facilitates the transmission of monetary policy. Therefore, the central government should pay more attention to the coordination of monetary and local government fiscal policies. (2) Local government competition tends to attenuate the transmission efficacy of monetary policy and undermine the effectiveness of local fiscal interventions, thereby impeding policy coordination and jeopardizing fiscal sustainability at the local level. In contrast, cooperative interactions among local governments yield beneficial outcomes. The central government should actively promote the establishment of a regional development mechanism that emphasizes joint construction, sharing, and collaboration, allowing intergovernmental competition to transition into intergovernmental cooperation. This shift will accelerate the creation of a unified national market and enhance the market-based allocation of resources, thereby increasing policy effectiveness. (3) Efforts to enhance the coordination between monetary and local fiscal policies, as well as to promote local fiscal sustainability, must account for a comprehensive array of influencing factors. Additionally, it is crucial to encourage the development of local government bond markets, reduce financial friction for local governments and the associated credit premiums, and impose some institutional constraints, like accounting for the propensity of local governments to incur excessive debt and strengthening the fiscal relationship between central and local governments.

Future research could explore the following: (1) the mechanisms facilitating coordination between monetary policy and local government fiscal policies—considering the substantial magnitude of local government debt in China and the country’s shift toward a price-based monetary policy framework, a local government bond channel for monetary policy transmission may exist, and this channel represents a critical pathway for aligning monetary policy with local fiscal strategies; (2) the degree of coordination between monetary policy and local government fiscal policy—the divergence between the objectives of the central bank and those of local governments could be operationalized into an index that measures the degree of coordination between these policies—such an index would provide valuable empirical evidence to inform future policy analyses by quantifying the coordination gaps; (3) the indicators showing the dynamics of competition and cooperation among local governments.

The main limitations of this study are as follows: (1) Due to data limitations, the analysis does not account for provincial heterogeneity in the responsiveness of local government bond interest rates to monetary policy. Consequently, this restricts a deeper understanding of provincial differences in the coordination between monetary and local government fiscal policies. (2) Due to the limitations of the toolbox of policy games provided by Bodenstein et al. [

13], the number of local government games in this study is only two, which does not provide a rich analysis related to the forms of local government competition and cooperation.