4.2.2. tvSURE Estimation Results Without and with Institutional Quality Proxies

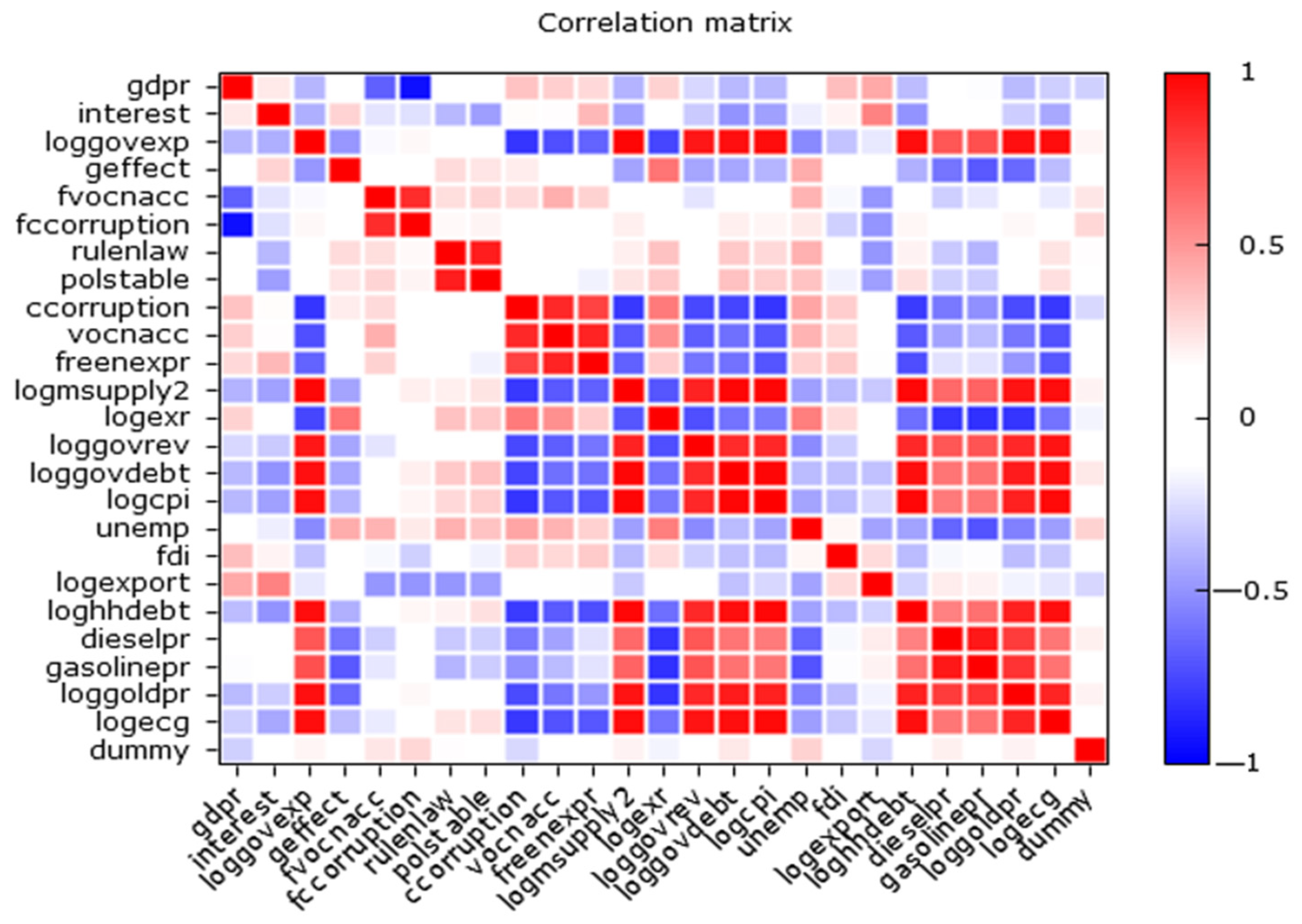

This section discusses the empirical findings of the study on how IQ influenced macroeconomic policy-driven growth in Thailand over the period from Q1: 2003 to Q4: 2023, based on tvSURE model estimations. The results were visualized in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, and all figures incorporated 90 percent bootstrap confidence intervals based on 100 runs to ensure robust findings. The analysis was disaggregated into monetary policy (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), denoted MPWIQ, and fiscal policy (

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16), denoted FPWIQ. The final selected IQ proxies by the combination of BART and BASAD models were transformed into interaction terms (IQ proxies × real GDP growth). The inclusion of interaction terms explores their moderating effects on the growth–macroeconomic policy correction.

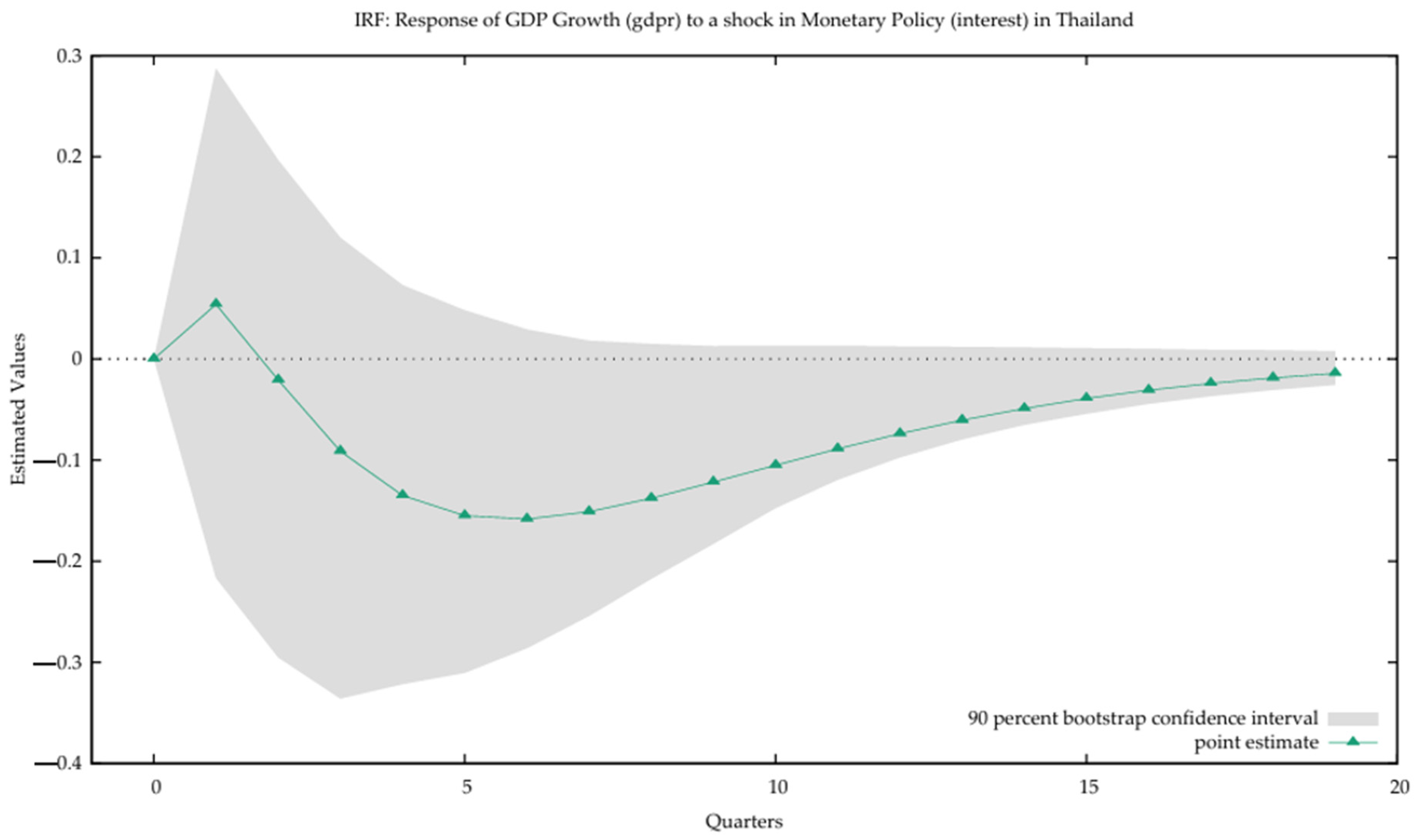

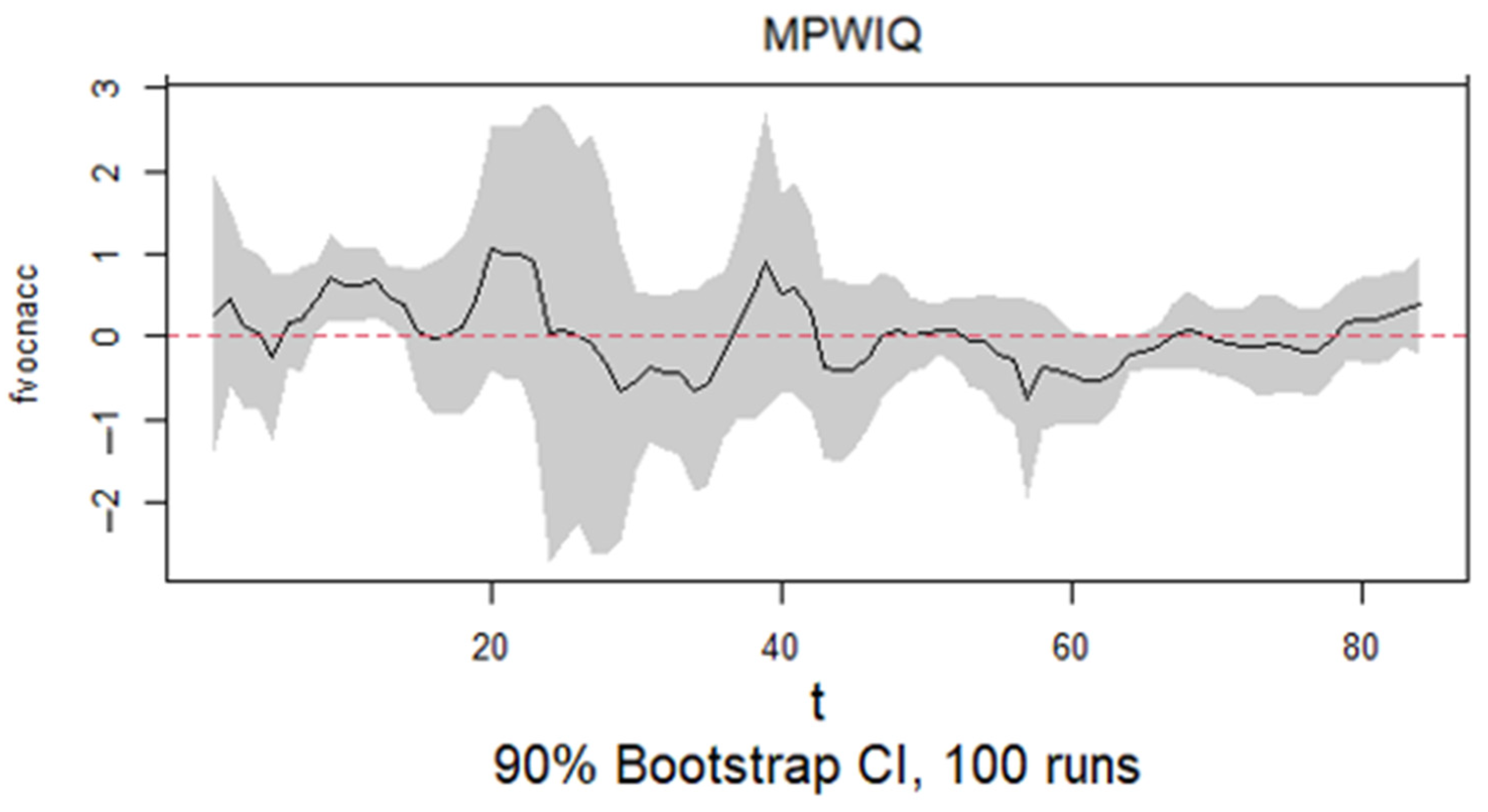

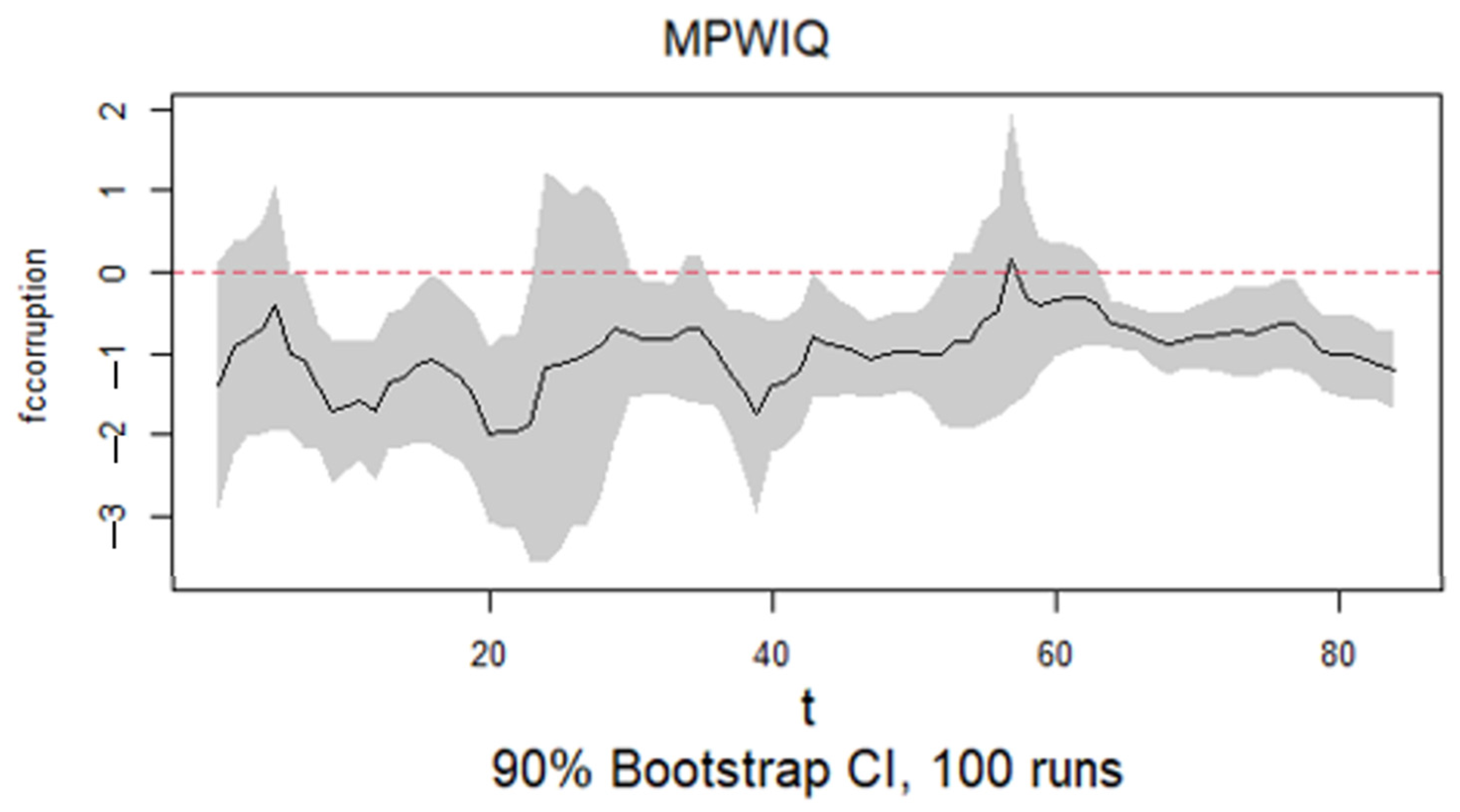

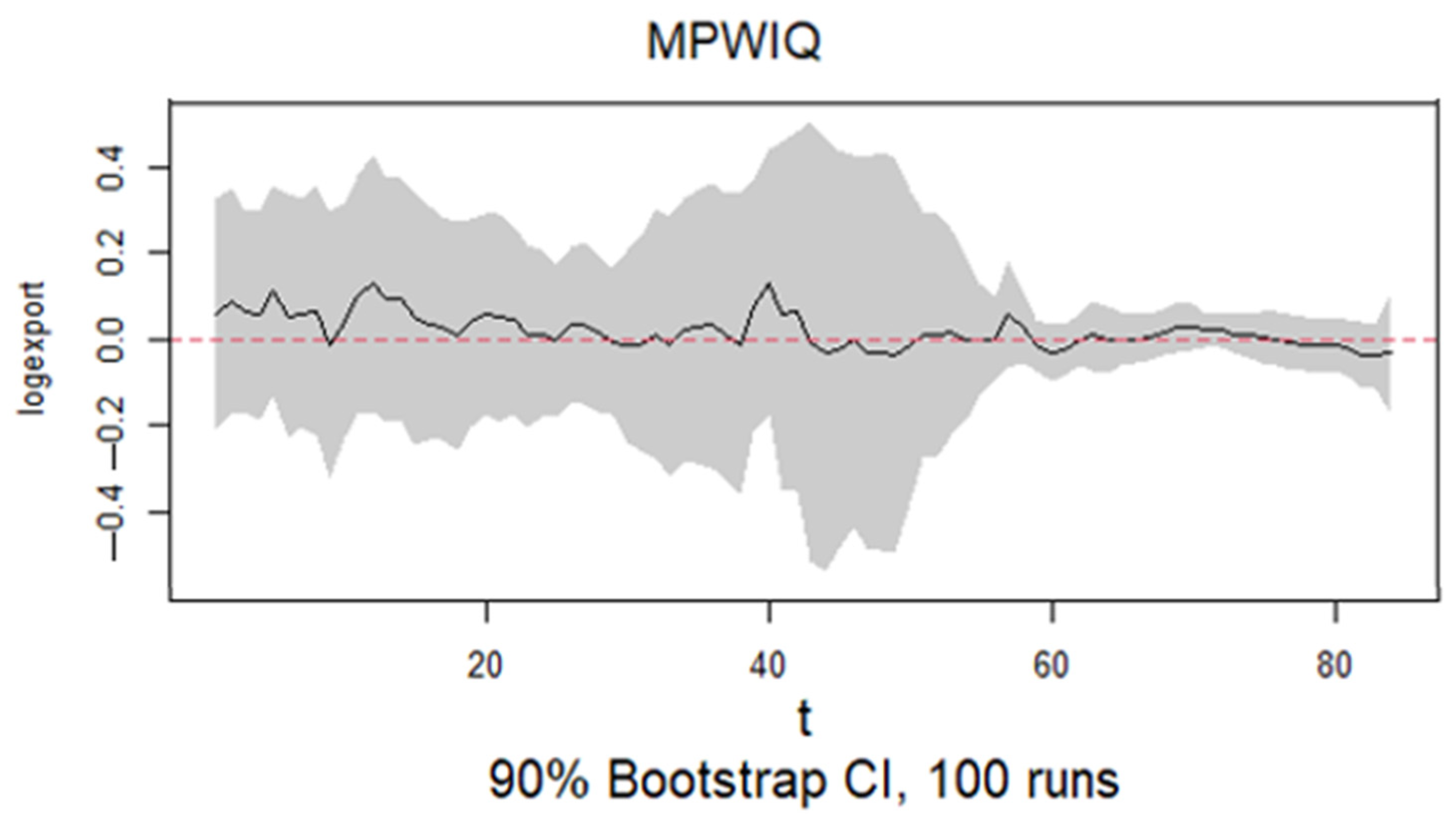

Policy interest rates (interest) positively affected economic growth during around Q2: 2013 to Q4: 2013 and again around Q4: 2014 to Q1: 2015 with effects between 0.1 and 0.2 (

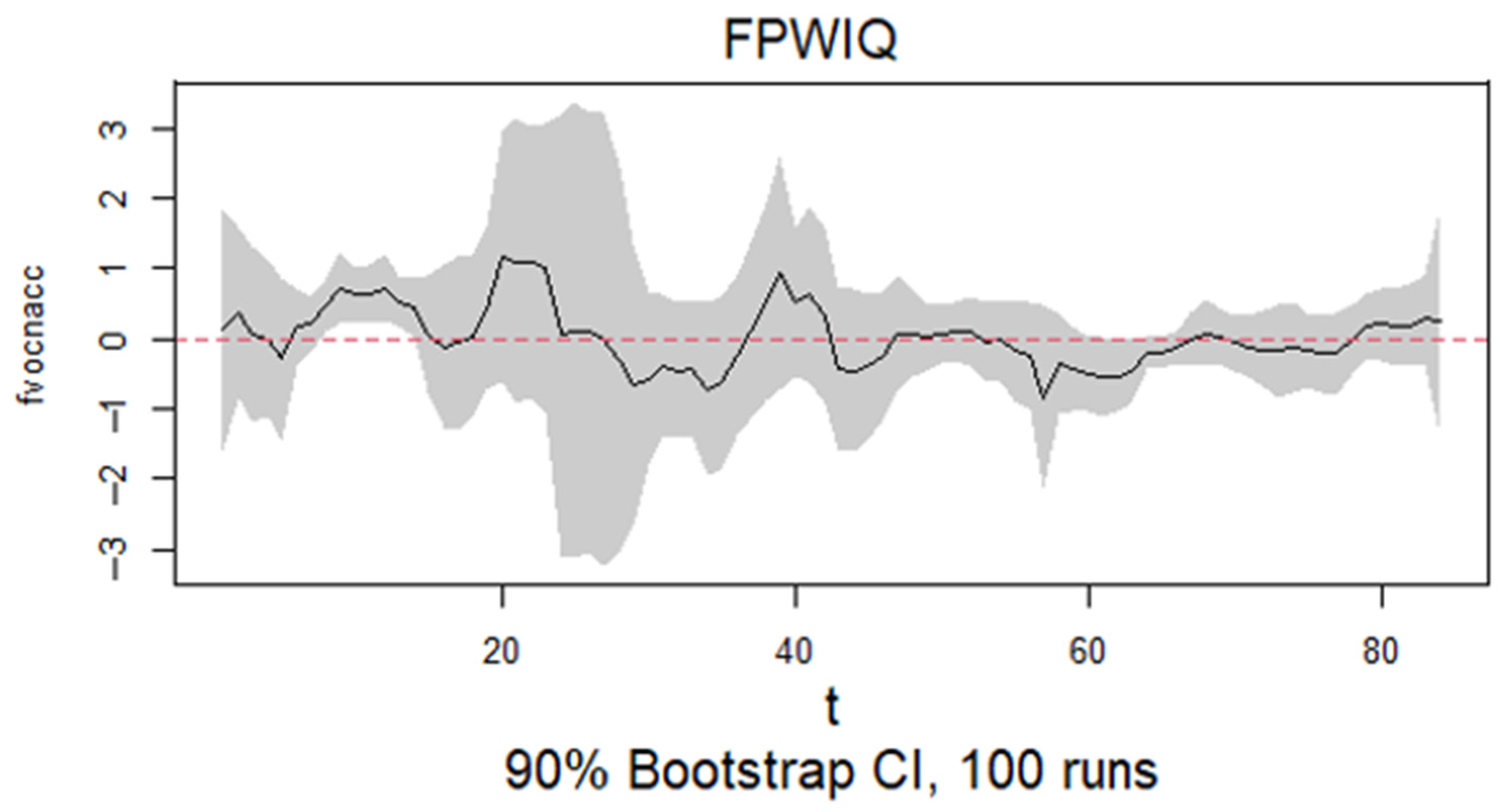

Figure 2). Outside these periods, their impact was mostly neutral. The interaction term of voice and accountability (fvocnacc) showed large fluctuations over the years, with some quarters sustaining growth and other times slowing it (

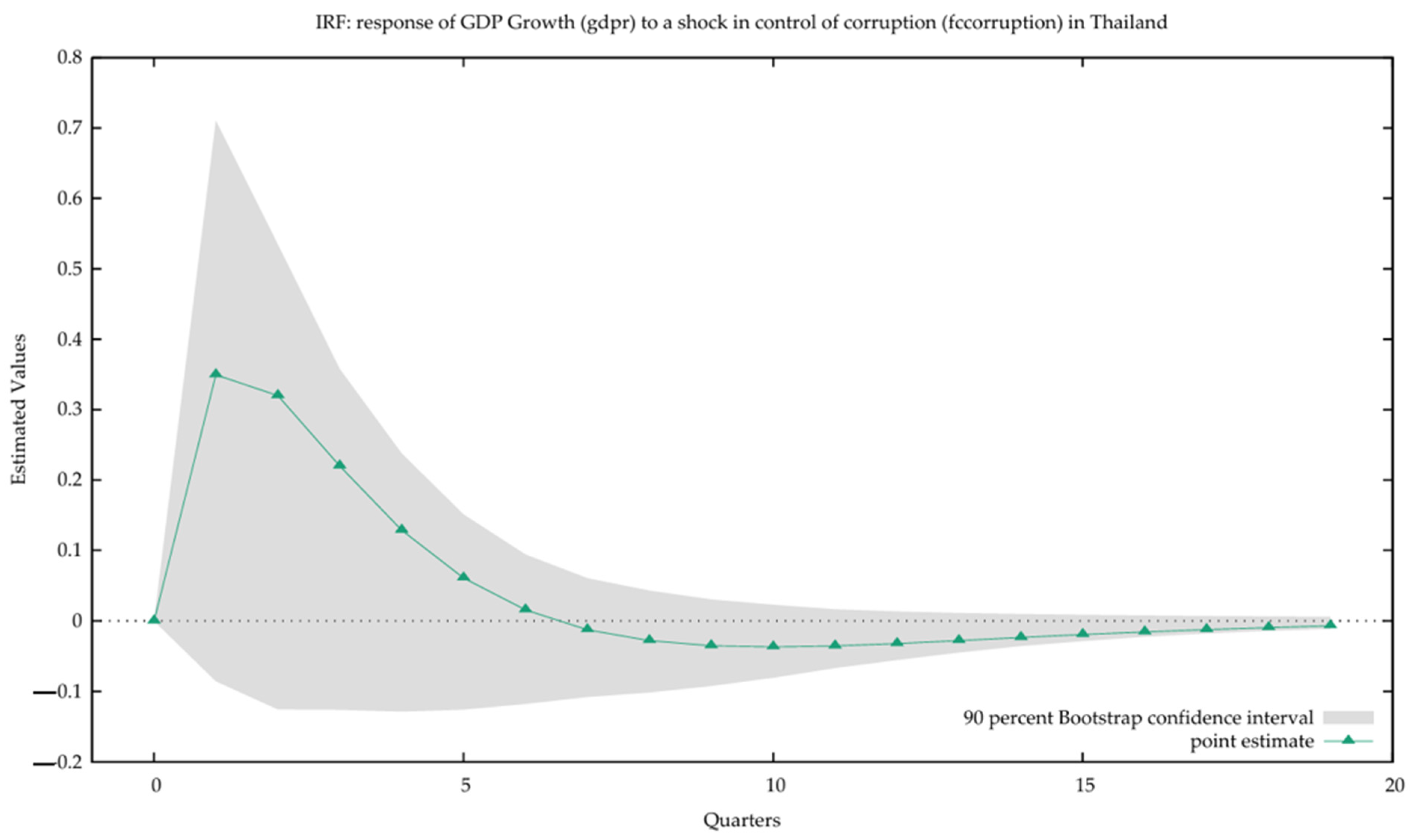

Figure 3). The second interaction term of IQ proxy, control of corruption, generally had a negative effect on growth throughout the period except for a brief positive influence around Q1:2017 (

Figure 4). Exports mostly supported growth except during around Q2: 2014 to Q4: 2014, Q4:2015 and late 2021 to 2023 when their effects weakened (

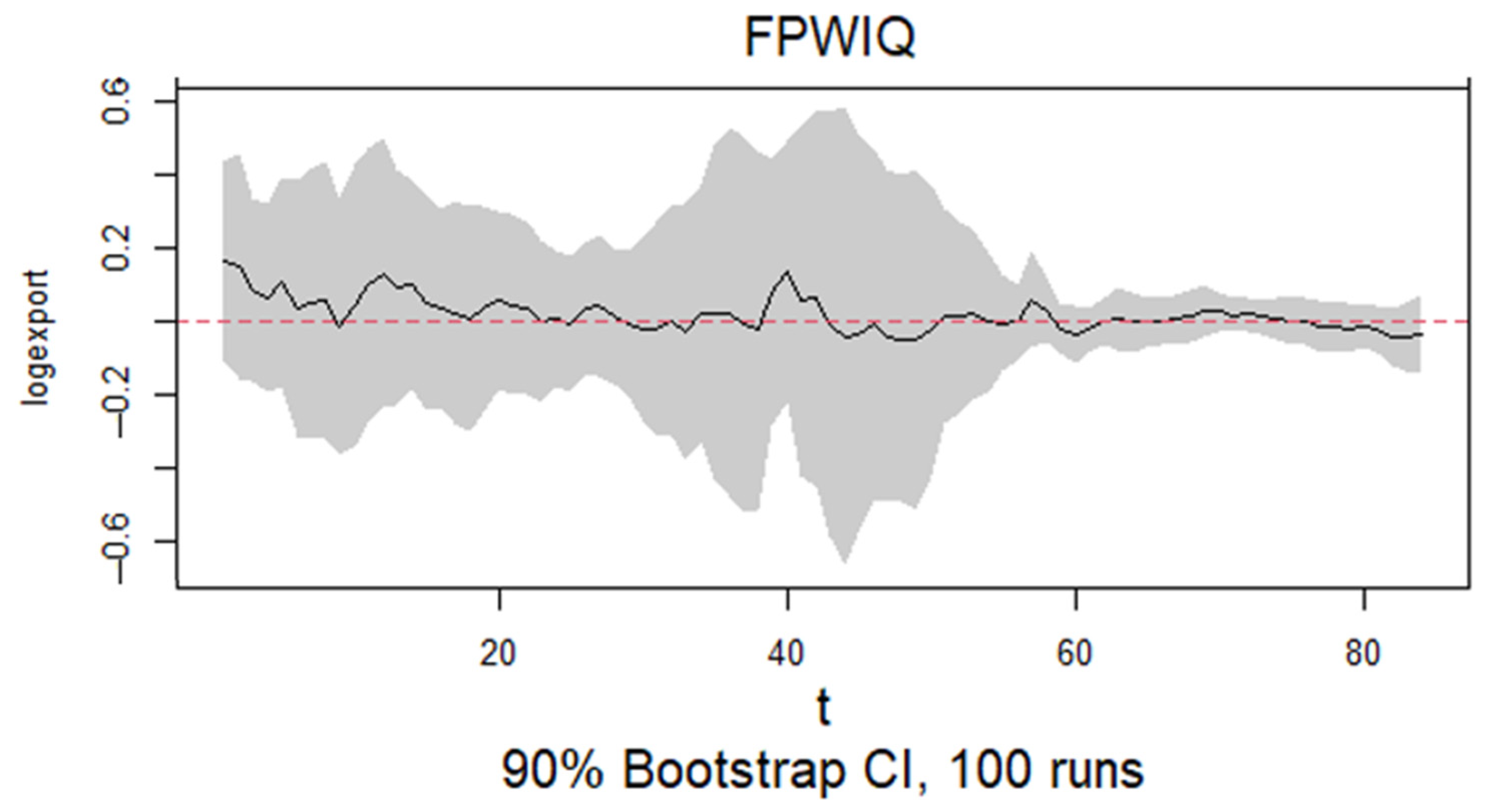

Figure 5). Gold prices negatively affected growth in 2007, 2009, and again in late 2022 (

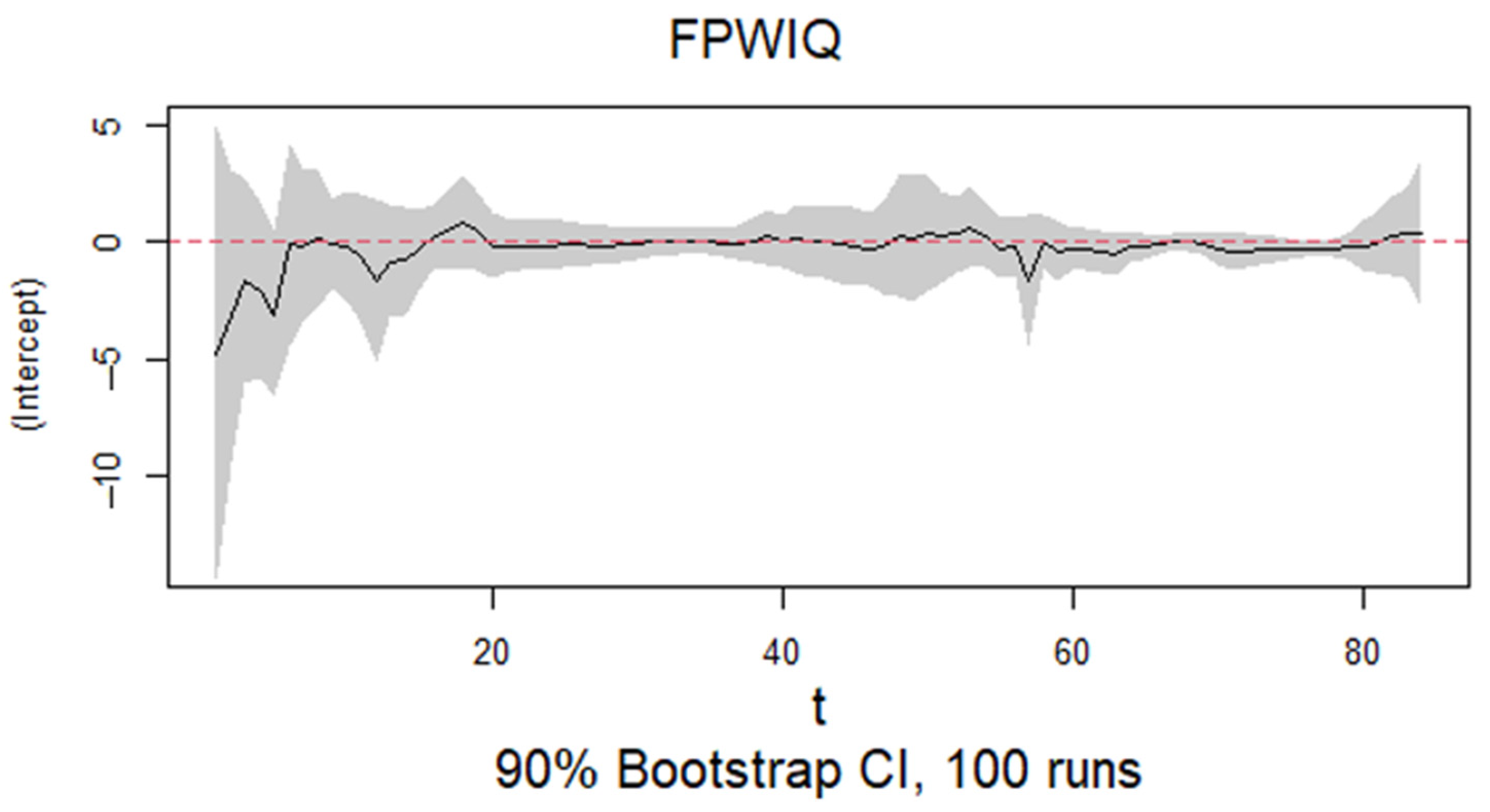

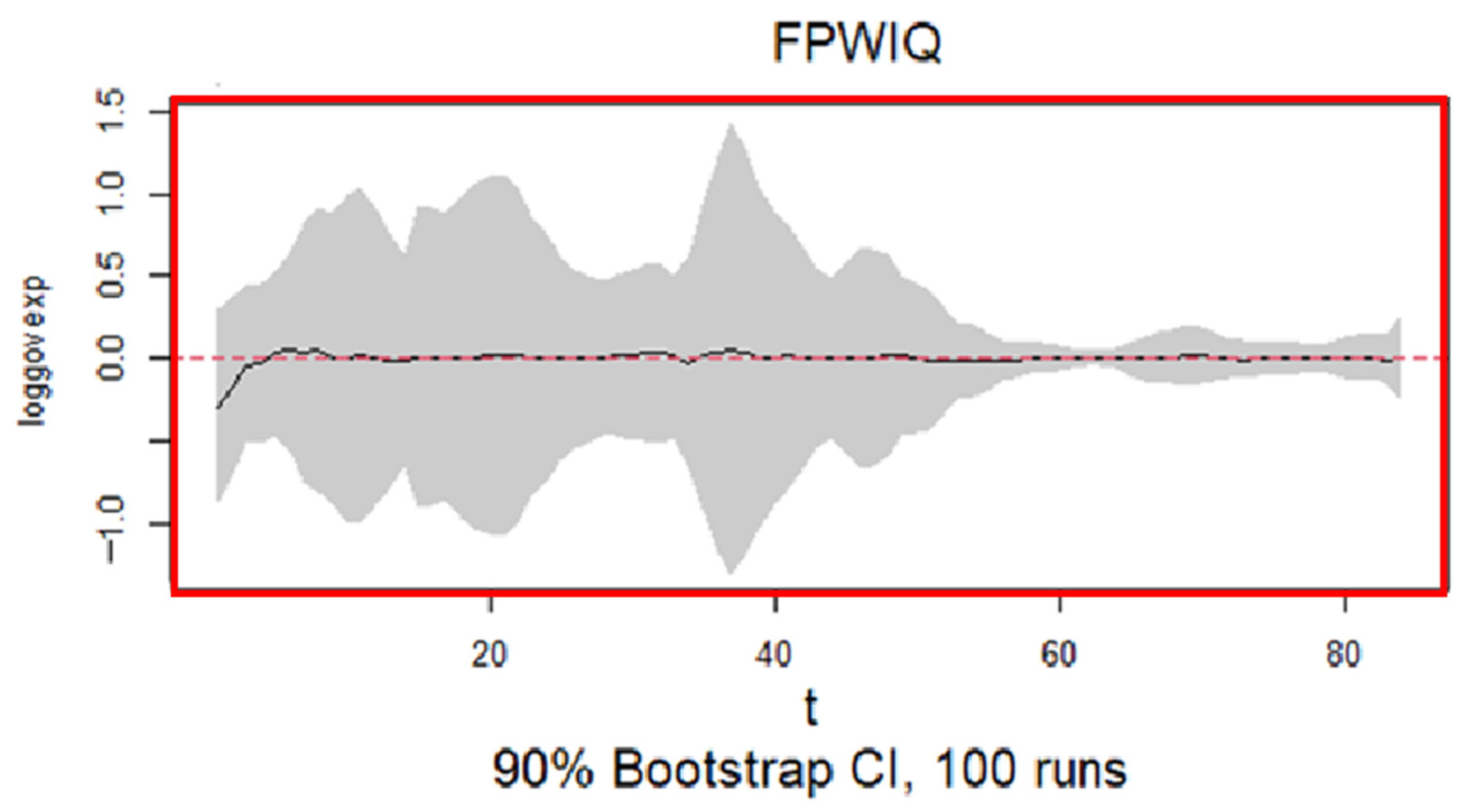

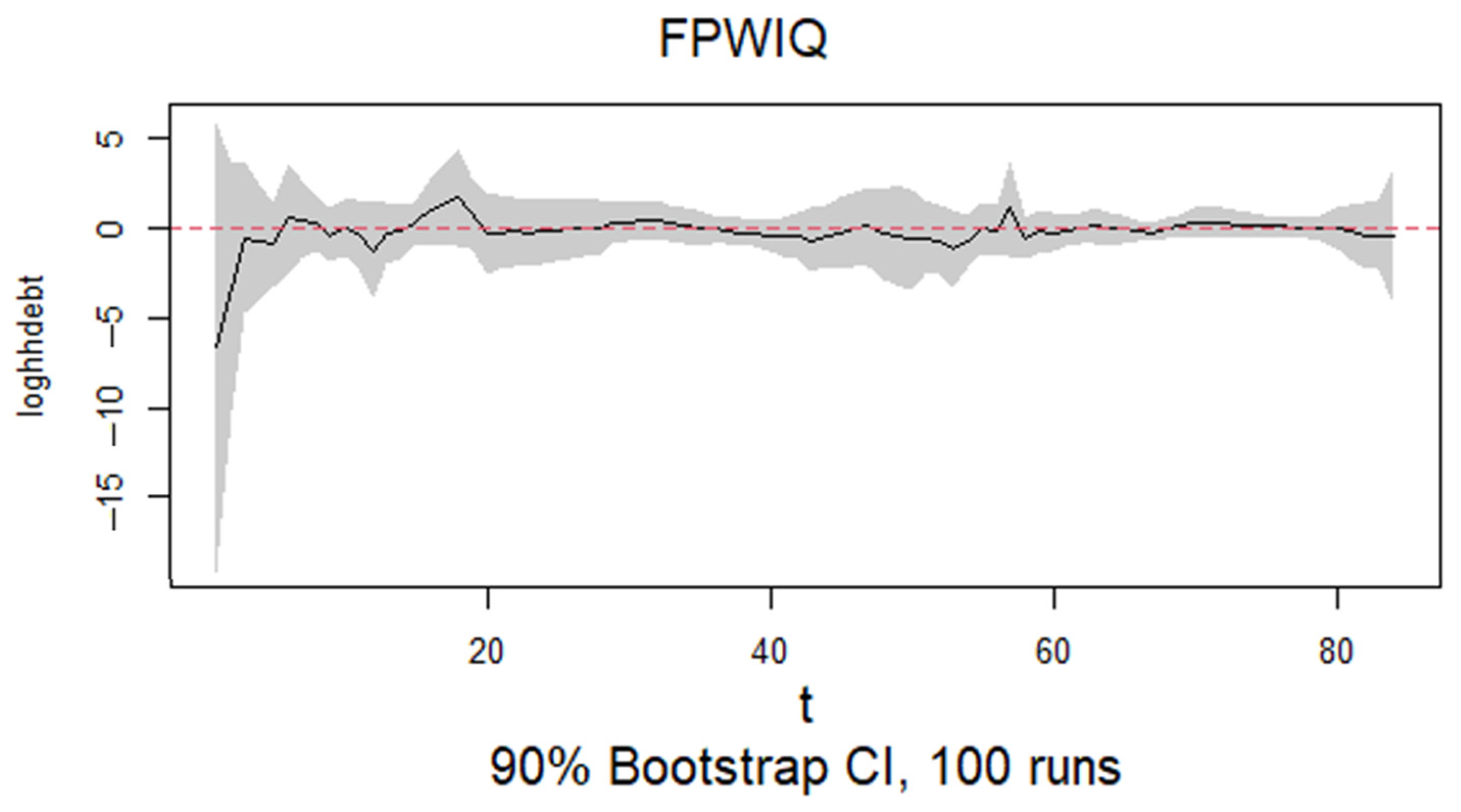

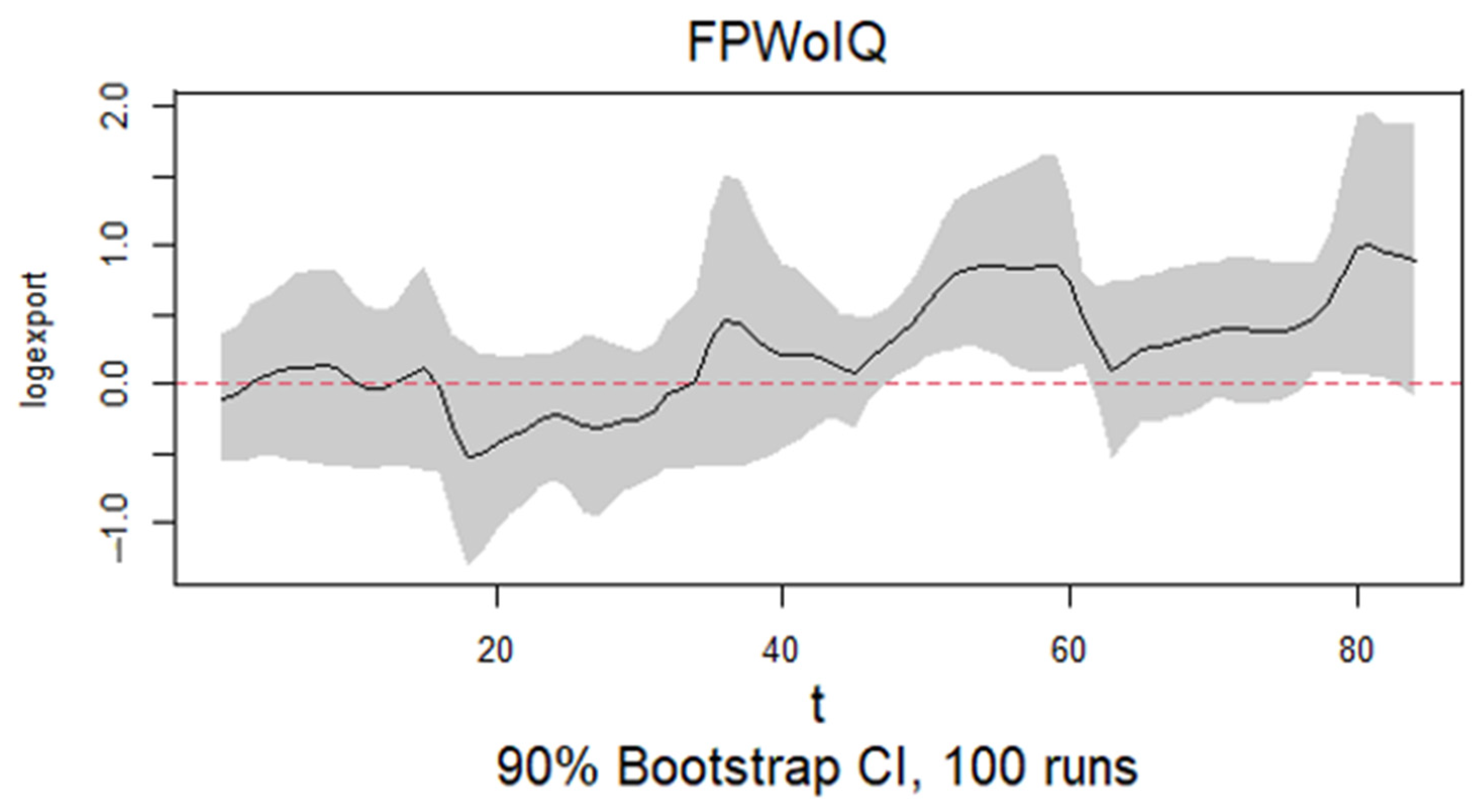

Figure 6). Household debt increased its positive impact on growth until about Q1: 2019 then stabilized, while electricity generation dipped mid-period but rose again by Q4: 2023. This indicates increasing support for growth. On the other hand, fiscal policy (loggovexp) showed a different pattern. It remained frequently neutral in its effect on growth throughout the entire period from Q1: 2003 to Q4: 2023 with minimal fluctuations. The interaction term of IQ proxy (voice and accountability) displayed strong fluctuations with positive effects around Q4: 2007 to Q2: 2008, Q2: 2012 to Q3: 2012, and Q2: 2022 to Q2: 2023, while showing negative effects during other times. The other interaction term of IQ proxy, control of corruption, consistently showed a negative relationship with growth except for a brief positive effect around Q1: 2017. Exports (

Figure 13) mostly supported growth but weakened during Q1: 2014 to Q4: 2014, Q1: 2017 to Q2: 2017 and Q2: 2022 to Q4: 2023. Gold prices (

Figure 14) also had a slight negative impact on growth with a more noticeable drop to about −0.3 in the last quarters of the study around Q2: 2022 to Q4: 2023. In sum, these results showed that monetary policy worked differently over time. Interest rates helped growth only in some periods. Policy effects changed with Thailand’s political and institutional shifts. The strong positive impact in Q2: 2013–Q1: 2015 came after political stabilization following the 2011 floods. It occurred before the 2014 military coup. Sharp changes in IQ proxies during 2006 and 2014 match the coups in those years. These events disrupted governance continuity. Voice and accountability improved briefly in 2012 and 2022–2023. These gains linked to constitutional reforms and decentralization initiatives. Control of corruption turned positive around 2017. This matched major anti-corruption campaigns. IQ fell during unrest such as the 2010 protests. This weakened policy transmission. External shocks and shifts in local confidence also shaped results. Institutional effects were not stable over time.

We also found that individual coefficient paths vary across

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20,

Figure 21,

Figure 22,

Figure 23,

Figure 24,

Figure 25,

Figure 26,

Figure 27 and

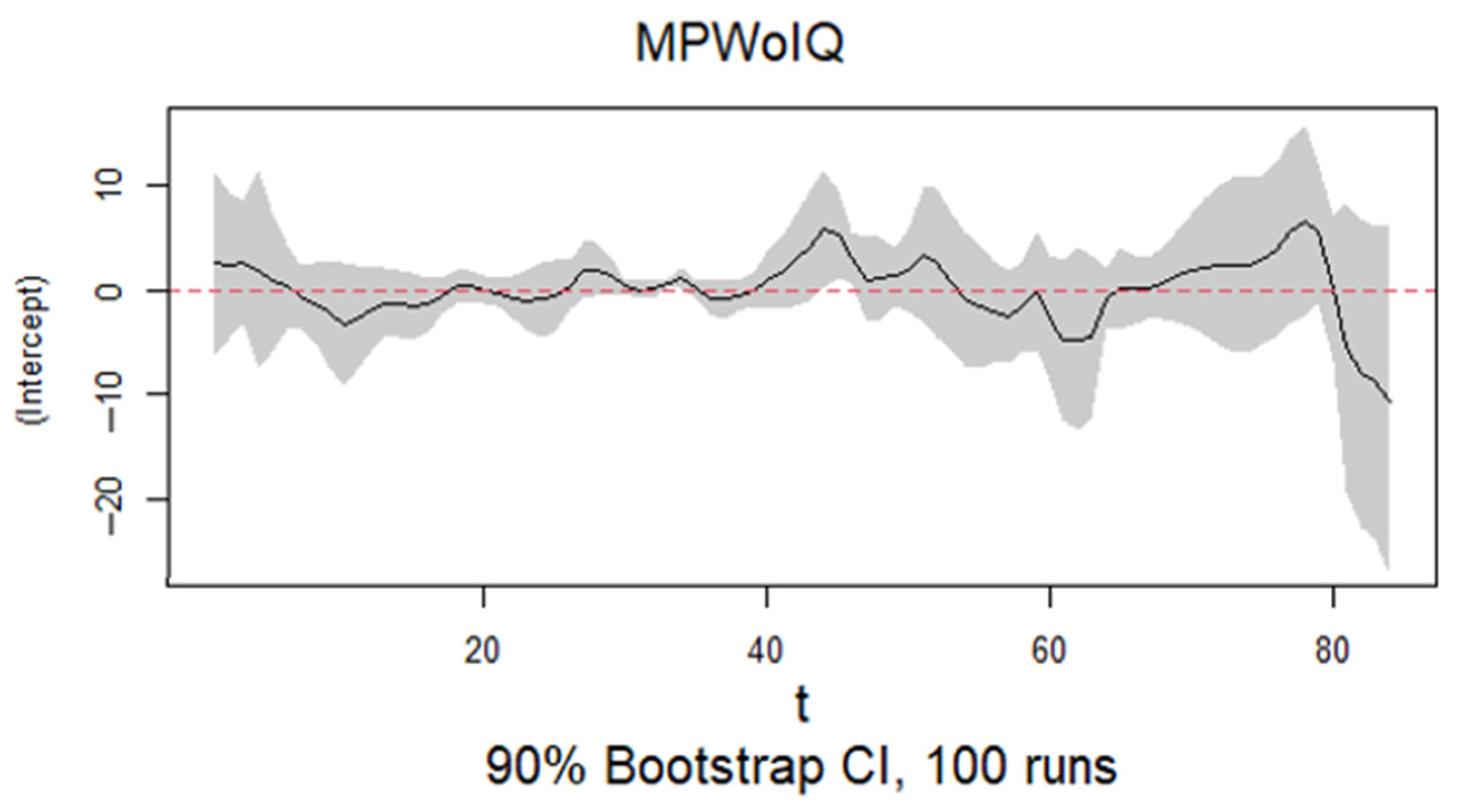

Figure 28. Several broader patterns appear. Monetary policy interest rates had positive effects only in short periods. For most of the time, the effect was neutral. This means their growth impact in Thailand was episodic, not constant. Fiscal policy effects stayed close to zero, with or without IQ proxies. This shows a generally neutral role. Institutional quality interactions were unstable. Voice and accountability switched between positive and negative effects. Control of corruption was mostly negative in the short run. This may reflect the costs of reform. The same macroeconomic controls like exports, gold prices, household debt, and electricity generation which were important in both policy areas. Their influence also changed with global and domestic shocks. The growth, policy and institution links are highly dynamic. Moreover, growth in exports improves growth but the effect is time varying. This shows risk from shocks of global trade. Gold prices fall when growth rises. During crises, this may show fear, while rising household debt tends to have a positive effect on growth. Electricity generation may reveal the quality of infrastructure. Its rise comes late but may promote long-term growth. Fiscal policy shows weak time effects. This may mean poor systems or slow results. Its link with institutions also changes. This may indicate a need for better governance institutions. Overall, stronger policy coordination is needed. Monetary, fiscal, and institutional tools must work together to support growth. These quarterly findings from Q1:2003 to Q4:2023 provide a broad understanding of the role of governance in economic resilience and effective policy design in Thailand for long-run and sustainable economic growth. This could be similar in emerging economies, as Thailand is an emerging economy.

In addition, the comparison between models with and without the moderating role of IQ proxies showed some changes in the estimated effects of macroeconomic policies and economic growth. The tvSURE model estimates without IQ proxies revealed that policy interest rates (

Figure 18) had significant negative effects on growth around Q2: 2013 to Q1: 2015. The effect fluctuated throughout the study period. In the model with IQ proxies (

Figure 2), this effect was flatter and remained close to zero throughout the sample quarters. In fact, it positively affected economic growth especially during around Q2: 2013 to Q4: 2013 and again around Q4: 2014 to Q1: 2015 with effects between 0.1 and 0.2 (

Figure 2). Similarly, fiscal policy measured by government expenditure (

Figure 24) in the model without IQ proxies had large and consistent negative effects especially from Q2: 2010 to Q4: 2018. When IQ proxies were included (

Figure 10), the effects of government expenditure exposed a different pattern. It remained frequently neutral, exhibiting around zero in its effect on economic growth from Q1: 2003 to Q4: 2023 with very low fluctuations. Overall, models excluding IQ overstate the size and stability of policy effects. Including IQ proxies yields more realistic and nuanced estimates. This has validated that strong institutions are crucial for sustainable and effective macroeconomic policy.

Interestingly, the control of corruption shows a negative or unstable effect on growth in the short run. This may be due to the costs of reform. Fighting corruption can disrupt the economy and face resistance from powerful groups. These changes take time to show positive effects. Thailand’s political history adds to the challenge. The country has faced coups, constitutional changes, and unrest. Political instability makes it hard to enforce reforms. It creates uncertainty for investors and policymakers. This slows growth and weakens institutions Therefore, the negative impact reflects these short-term disruptions. It also shows how political instability affects governance. Strong institutions help growth, but only with stable politics and support for reform.

These findings support the importance of IQ in shaping the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies. Moreover, models that omit IQ proxies tend to exaggerate both the magnitude and stability of policy effects. These findings confirm that the inclusion of institutions leads to more realistic estimates. This study thus concludes that strong institutions are essential for effective public policy performance and sustainable growth for the Thai economy between 2003 and 2023. Besides, monetary and fiscal policies alone are insufficient without supportive governance. Addressing political instability and improving reform implementation are key to unlocking sustainable growth.

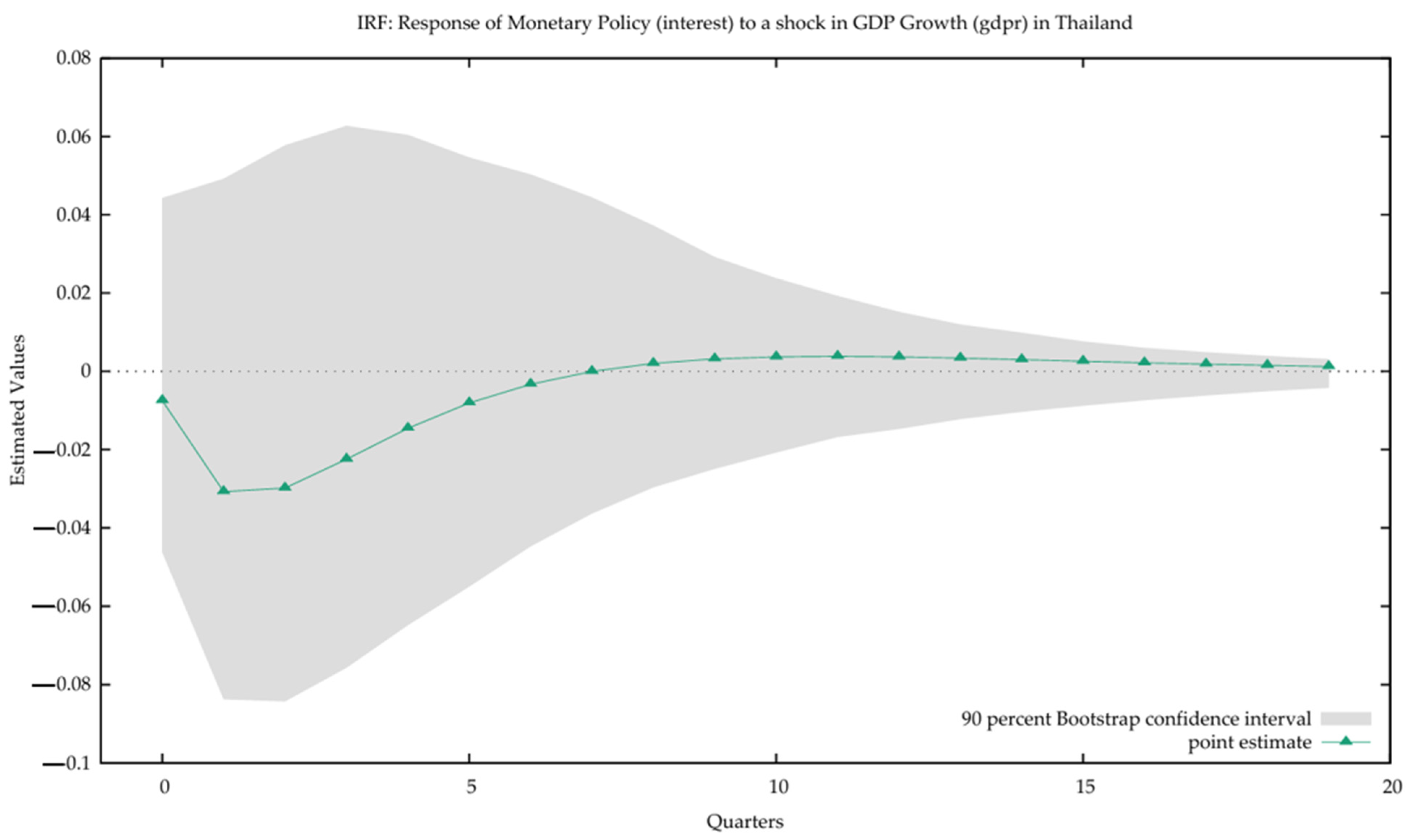

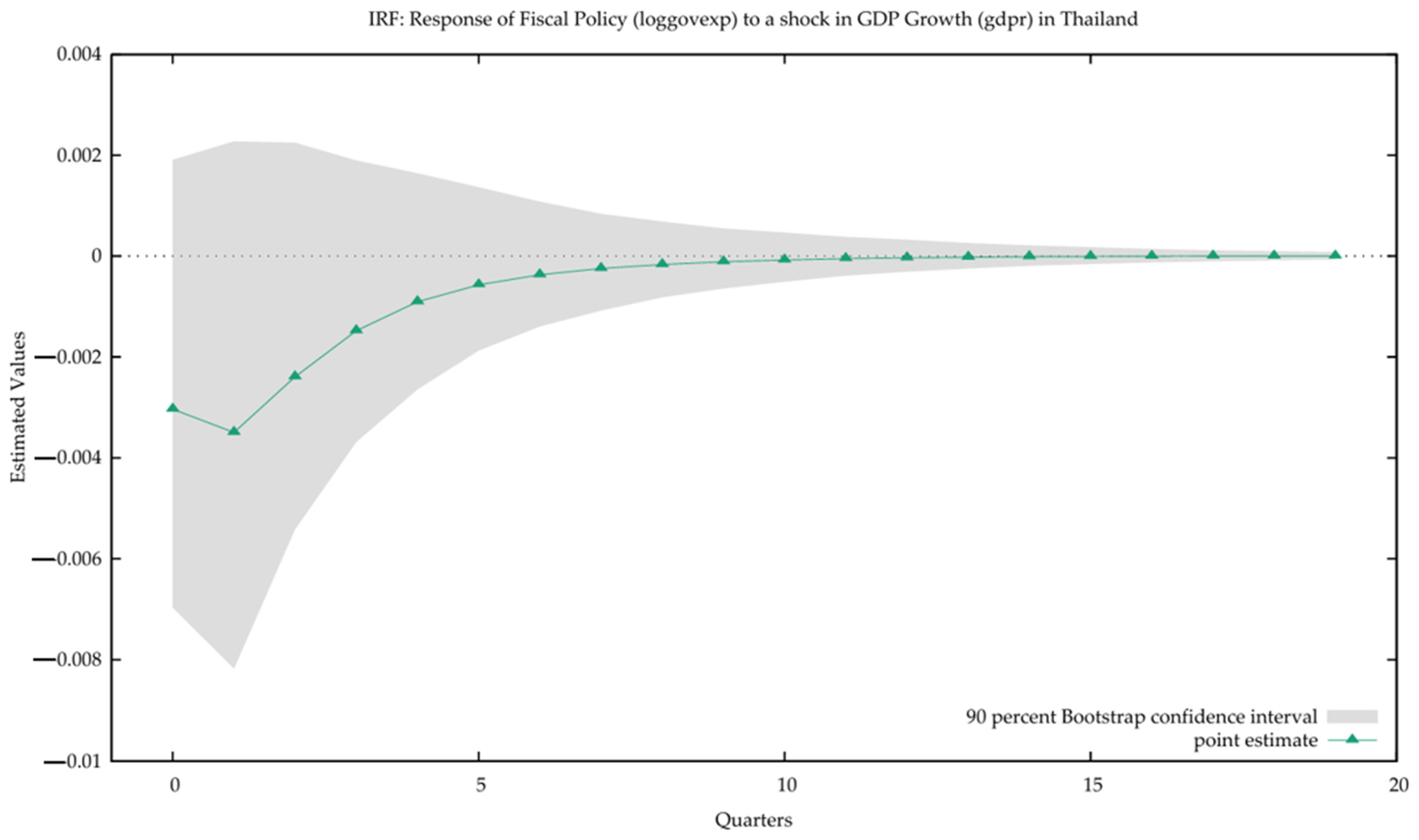

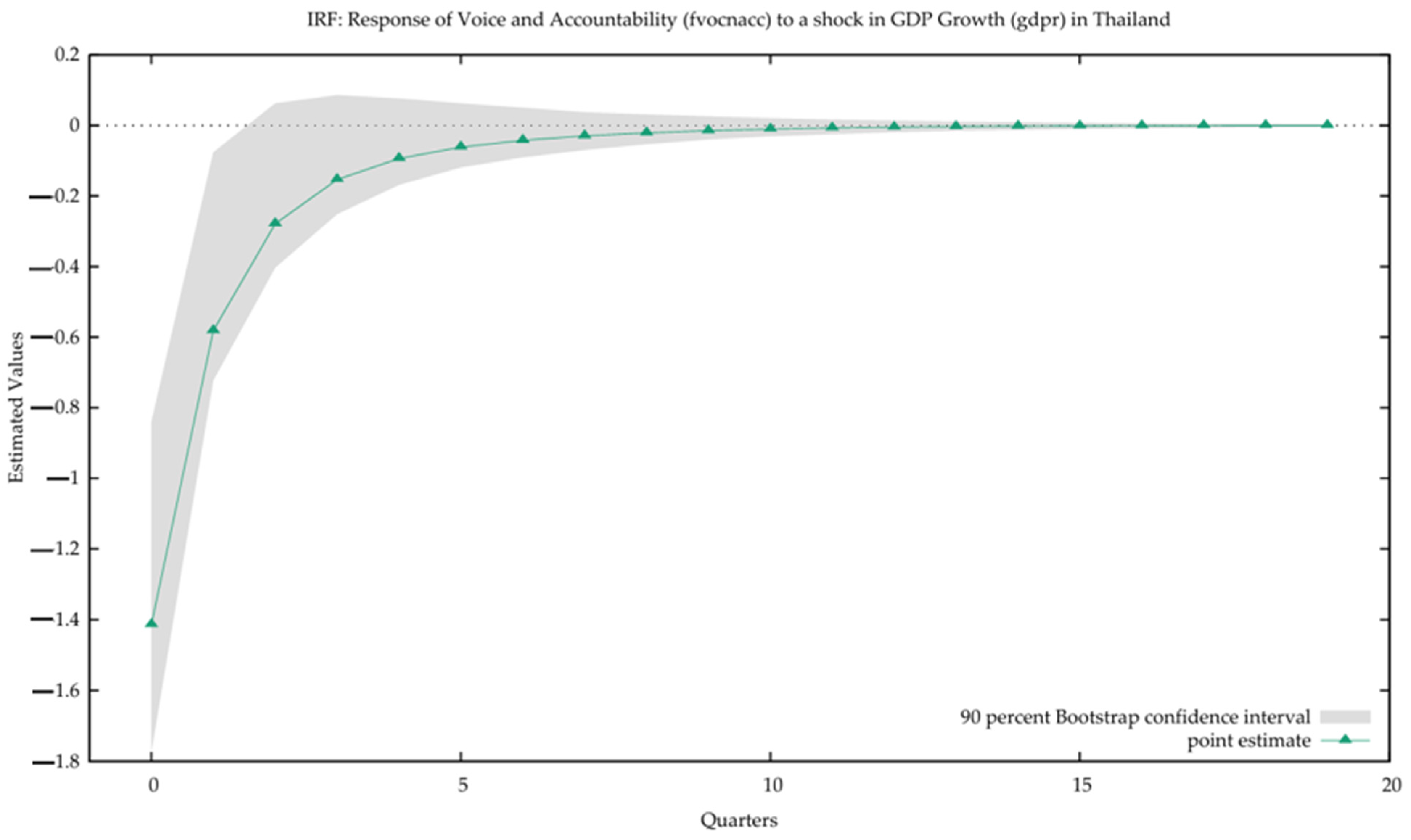

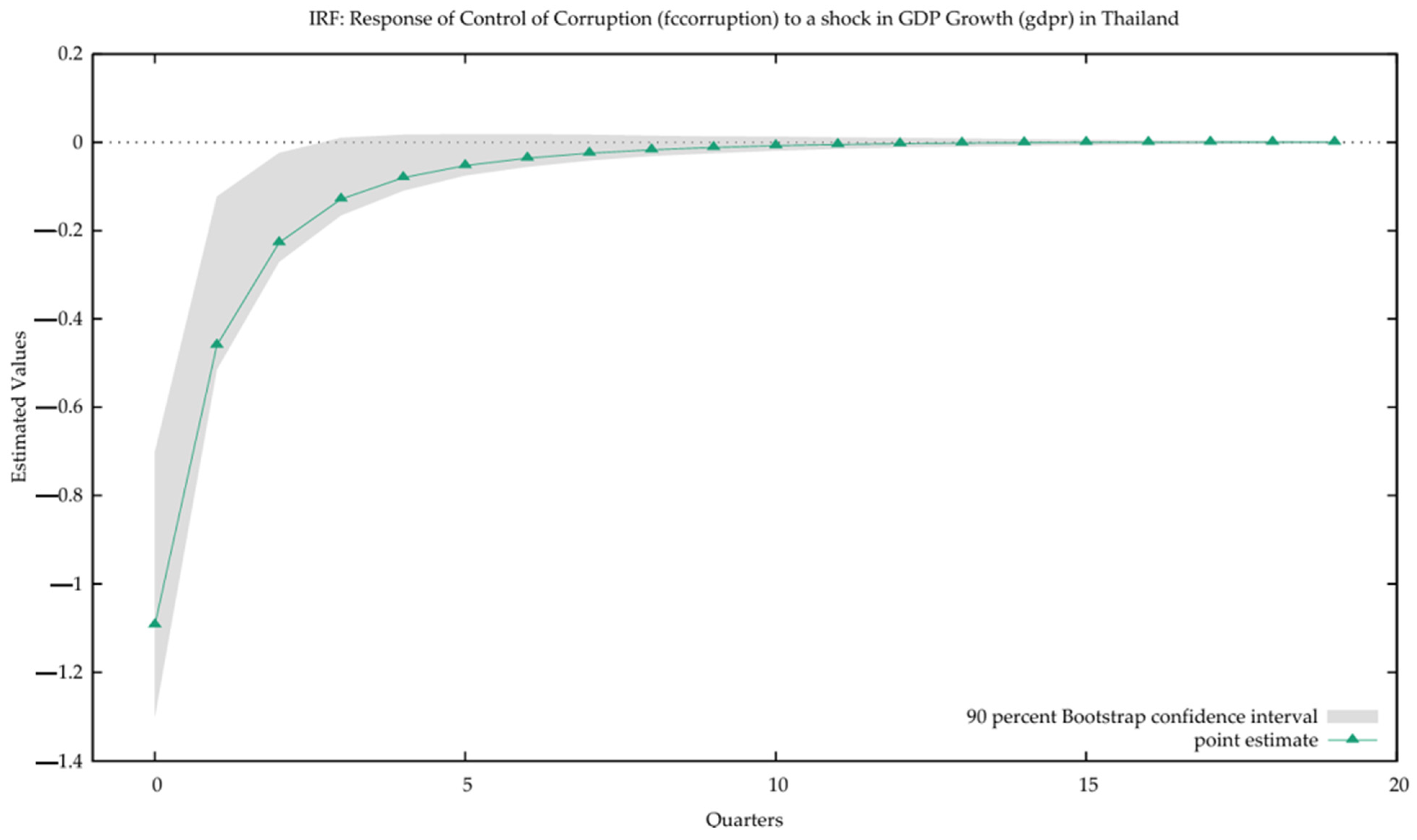

To check the robustness, we employed a vector autoregression with exogeneous variables (VARX) model. Sims [

51] first proposed the model VAR and it has been widely used to study dynamic associations between macroeconomic variables and policy shocks. The VAR model allows adding exogenous variables to the system considering the outside influences. Important studies using VARX include [

52,

53]. We choose this model because it is effective to examine the interactions of fiscal and monetary policies, IQ, and growth well. It serves as a good check alongside the main tvSURE model. For this, we used the same variables selected by the coordination of BART and BASAD approach. The VARX results support the main findings. Macroeconomic policies and institutions jointly affect economic growth in Thailand. Interest rates respond to changes in both GDP growth and IQ. This confirms the interaction effects found in the main model. Government spending shows inertia. This supports the neutrality of fiscal policy in the tvSURE estimates. Exogenous variables such as exports and household debt also play a role. They influence policy responses, especially across different periods. This model performs well and reveals consistent patterns (

Appendix C). Impulse response functions (IRFs) are reported in

Appendix D. These IRFs present how policies react to shocks in GDP growth and vice versa. Government spending declines in the first two quarters. It turns positive after the fourth quarter. Policy interest rates fall slightly at first. But the effect remains near zero afterward. These results suggest moderate policy responses to output shocks. There is little evidence of strong fiscal or monetary expansions (

Appendix D).