How Awareness of Organic JAS and RSPO Labels Influences Japanese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay More for Organic Cosmetics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does awareness of the Organic JAS label influence Japanese consumers’ WTPM for organic cosmetics?

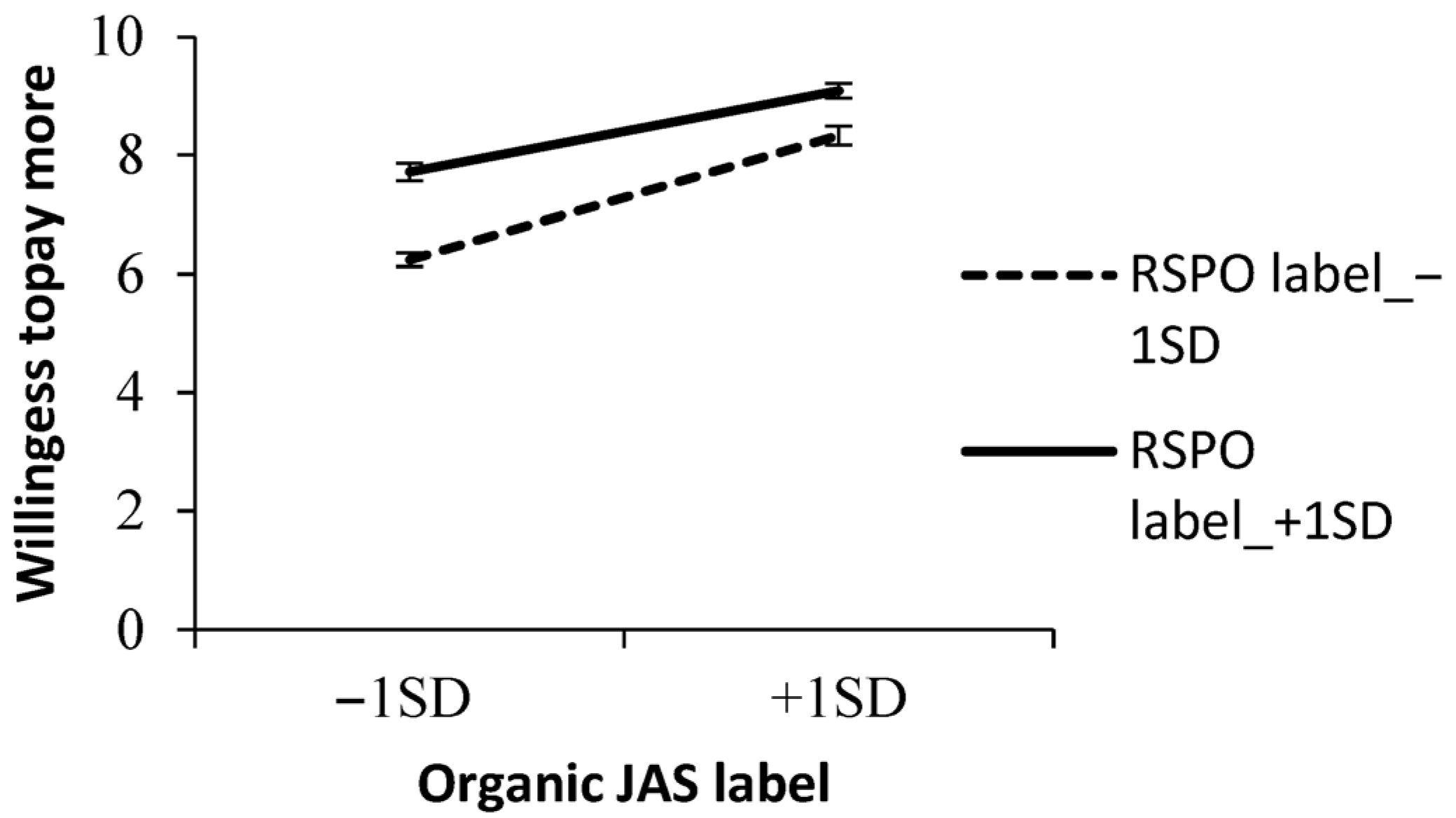

- How does awareness of the RSPO label moderate this relationship? Does it strengthen or weaken the effect of Organic JAS awareness on WTPM?

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Consumer’s Green Buying Behaviors on Cosmetics

2.2. Eco-Label Effects on Green Products

2.2.1. Consumer Awareness

2.2.2. Eco-Labels and Sustainable Behavior

2.3. Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measurement Model

3.2.1. Dependent and Independent Variables

3.2.2. Control Variables

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Results

4.2. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.; Yang, S.; Hanifah, H.; Iqbal, Q. An Exploratory Study of Consumer Attitudes toward Green Cosmetics in the UK Market. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Rosenthal, S. Signaling the Green Sell: The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer Trust. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret, J.K.; Gómez Velázquez, A.; Mehn, A. Green Cosmetics—The Effects of Package Design on Consumers’ Willingness-to-Pay and Sustainability Perceptions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Understanding the Determinants of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Products: An Empirical Analysis of the China Environmental Label. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2012, 5, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozza, A.; Campi, C.; Garelli, S.; Ugazio, E.; Battaglia, L. Current Regulatory and Market Frameworks in Green Cosmetics: The Role of Certification. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 30, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, W.I.; Lemken, D.; Spiller, A.; Schulze, M. Welcome to the (Label) Jungle? Analyzing How Consumers Deal with Intra-Sustainability Label Trade-Offs on Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Psychological Determinants of Paying Attention to Eco-Labels in Purchase Decisions: Model Development and Multinational Validation. J. Consum. Policy 2000, 23, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C. Traceability the New Eco-Label in the Slow-Fashion Industry?—Consumer Perceptions and Micro-Organisations Responses. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6011–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Siwar, C. Measuring Consumer Understanding and Perception of Eco-labelling: Item Selection and Scale Validation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sahadev, S.; Wei, X.; Henninger, C.E. Modelling the Antecedents of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Eco-labelled Food Products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1256–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon Kim, H.; Chung, J. Consumer Purchase Intention for Organic Personal Care Products. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo-Thi-Ngoc, H.; Nguyen-Viet, B.; Hong-Thach, H. Purchase Intention for Vegan Cosmetics: Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241240548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, A.; Nagai, M. Relationship between Certification and Biodiversity Related to Sustainable Cosmetics. In Memoirs of the Faculty of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences; University of Fukui: Fukui, Japan, 2023; Volume 7, pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wassmann, B.; Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Palm Oil Roundtable Sustain. Palm Oil (RSPO) Label: Are Swiss Consum. Aware. Concerned? Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 103, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg, N.; Fogarassy, C. Green Consumer Behavior in the Cosmetics Market. Resources 2019, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, A.; Taneja, S.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Hey, Did You See That Label? It’s Sustainable!: Understanding the Role of Sustainable Labelling in Shaping Sustainable Purchase Behaviour for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 2820–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Lamb, P.; Peretiatko, R. Green Decisions: Demographics and Consumer Understanding of Environmental Labels. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability Labels on Food Products: Consumer Motivation, Understanding and Use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, S.; Mahowa, V. Investigating Factors That Influence the Purchase Behaviour of Green Cosmetic Products. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 13, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Chen, K. A Study on Green Cosmetic Brand Equity and Purchase Intentions. Am. J. Dermatol. Res. Rev. 2020, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellon, M.-C.; Rinaldi, M.-J.; Wernerfelt, A.-S. How Green Is Green? Consumers’ Understanding of Green Cosmetics and Their Certifications. In Proceedings of the International Marketing Trends Conference, Paris, France, 20–22 January 2011; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Rahman Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallgren, C.A.; Wood, W. Access to Attitude-Relevant Information in Memory as a Determinant of Attitude-Behavior Consistency. J. Exp. Social. Psychol. 1986, 22, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.; Widmar, R. Motivations and Barriers to Recycling: Toward a Strategy for Public Education. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 22, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yuan, Q. The Impact of Eco-Label on the Young Chinese Generation: The Mediation Role of Environmental Awareness and Product Attributes in Green Purchase. Sustainability 2019, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M.K.; Arvola, A.; Koivisto Hursti, U.; Åberg, L.; Sjödén, P. Attitudes towards Organic Foods among Swedish Consumers. Br. Food J. 2001, 103, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.-L.; Lanero, A.; García, J.A.; Moraño, X. Segmentation of Consumers Based on Awareness, Attitudes and Use of Sustainability Labels in the Purchase of Commonly Used Products. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Bae, J.; Kim, K.H. The Effect of Environmental Cues on the Purchase Intention of Sustainable Products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.; Siwar, C.; Talib, B.; Sarah, F.; Chamhuri, N. Synthesis of Constructs for Modeling Consumers’ Understanding and Perception of Eco-Labels. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2176–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond Ecolabels: What Green Marketing Can Learn from Conventional Marketing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisl, F.M.; Roe, B.; Hicks, R.L. Can Eco-Labels Tune a Market? Evidence from Dolphin-Safe Labeling. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2002, 43, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, M.C.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Consumers’ Valuation of Food Quality Labels: The Case of the European Geographic Indication and Organic Farming Labels. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Ji, H.; Vázquez-Brust, D.A. Third-Party Certification, Sponsorship, and Consumers’ Ecolabel Use. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is Ecolabelling? Available online: https://globalecolabelling.net/about/what-is-ecolabelling/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Horne, R.E. Limits to Labels: The Role of Eco-labels in the Assessment of Product Sustainability and Routes to Sustainable Consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Gale, F. Chinese Consumer Demand for Food Safety Attributes in Milk Products. Food Policy 2008, 33, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vocino, A.; Polonsky, M.J. The Influence of Eco-Label Knowledge and Trust on pro-Environmental Consumer Behaviour in an Emerging Market. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, M.; Tocco, B.; Yeh, C.-H.; Hartmann, M. What Determines Consumers’ Use of Eco-Labels? Taking a Close Look at Label Trust. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoi, S.; Fujino, M.; Kuriyama, K. Investigating Spatially Autocorrelated Consumer Preference for Multiple Ecolabels: Evidence from a Choice Experiment. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 7, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, G.; Carlucci, D.; Sardaro, R.; Roselli, L.; De Gennaro, B.C. Assessing Consumer Preferences for Organic vs Eco-Labelled Olive Oils. Org. Agr. 2019, 9, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Hu, W. The Accumulation and Substitution Effects of Multi-Nation Certified Organic and Protected Eco-Origin Food Labels in China. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 203, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-J.; Costello, J.P.; Koo, D.-M. The Impact of Consumer Confusion from Eco-Labels on Negative WOM, Distrust, and Dissatisfaction. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Human. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Which Are the Determinants of Green Purchase Behaviour? A Study of Italian Consumers. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 2600–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.D.; Trivedi, R.H.; Yagnik, A. Self-Identity and Internal Environmental Locus of Control: Comparing Their Influences on Green Purchase Intentions in High-Context versus Low-Context Cultures. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yoo, J.H.; Zhou, H. To Read or Not to Read: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Food Label Use. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakagami, M.; Sato, M.; Ueta, K. Measuring Consumer Preferences Regarding Organic Labelling and the JAS Label in Particular. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2006, 49, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Suwunnamek, O.; Toyoda, T. Consumer Attitude towards Organic Labeling Schemes in Japan. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2008, 20, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, N.; Moultrie, J.; Clarkson, P.J. Seeing Things: Consumer Response to the Visual Domain in Product Design. Des. Stud. 2004, 25, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Sustainability in the Food Sector: A Consumer Behaviour Perspective. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Youssef, A.; Abderrazak, C. Multiplicity of Eco-Labels, Competition, and the Environment. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2009, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brécard, D. Consumer Confusion over the Profusion of Eco-Labels: Lessons from a Double Differentiation Model. Resour. Energy Econ. 2014, 37, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostfeld, R.; Howarth, D.; Reiner, D.; Krasny, P. Peeling Back the Label—Exploring Sustainable Palm Oil Ecolabelling and Consumption in the United Kingdom. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Dash, S.P. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 7th (Global Edition) ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-292-26591-9. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, L.; Aitken, R. The Role of Young Consumers in Moving to a Sustainable Consumption Future. In Transitioning to Responsible Consumption and Production; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-03897-873-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kabaja, B.; Wojnarowska, M.; Cesarani, M.C.; Varese, E. Recognizability of Ecolabels on E-Commerce Websites: The Case for Younger Consumers in Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How Reliable Are Measurement Scales? External Factors with Indirect Influence on Reliability Estimators. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-813263-7. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P.; Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-4106-0449-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-8039-3287-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schena, R.; Morrone, D.; Russo, A. The Competition between Private Label and National Brand through the Signal of Euro-Leaf. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 6169–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao Releases Kao Sustainability Report 2025. Available online: https://www.kao.com/global/en/newsroom/news/release/2025/20250613-002/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

| Gender (N: 505) | Frequency Rate (%) | Age | Frequency Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Man | 5.35 | Aged 20–29 (or: In their 20s) | 24% |

| Woman | 94.65 | Aged 30–39 (or: In their 30s) | 55% |

| Aged 40 and above (or: 40 + years) | 21% | ||

| Total (N = 505) | 100% | 100% |

| N | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | ||||||||||

| Organic JAS label awareness | 505 | 7.44 | 2.22 | 1 | ||||||

| RSPO label awareness | 505 | 9.50 | 2.40 | 0.280 ** | 1 | |||||

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||||

| Intention to pay more for the product with Organic JAS label | 505 | 7.79 | 1.95 | 0.527 ** | 0.433 ** | 1 | ||||

| Control Variables | ||||||||||

| Gender | 505 | 0.95 | 0.225 | −0.043 | 0.025 | −0.088 ** | 1 | |||

| Age group 20s | 505 | 0.24 | 0.425 | 0.031 | −0.007 | −0.029 | −0.034 | 1 | ||

| Age group 30s | 505 | 0.55 | 0.498 | −0.036 | 0.035 | −0.003 | 0.069 | −0.617 ** | 1 | |

| Age group 40s | 505 | 0.21 | 0.405 | 0.023 | −0.020 | 0.048 | −0.053 | −0.283 ** | −0.566 ** | 1 |

| Constructs and Items | Factor Loading | CR | α | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic JAS label awareness | 0.699 | 0.618 | 0.442 | |

| Knowledge about the mark | 0.508 | |||

| Perceived health benefits | 0.745 | |||

| Perceived environmental benefits | 0.717 | |||

| RSPO label awareness | 0.799 | 0.718 | 0.580 | |

| Knowledge about the mark | 0.531 | |||

| Perceived health benefits | 0.880 | |||

| Perceived environmental benefits | 0.827 | |||

| Intention to pay more for the product with Organic JAS label | 0.863 | 0.859 | 0.679 | |

| Price justification | 0.868 | |||

| Purchase intention despite the price | 0.849 | |||

| Perceived price justification | 0.750 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | β | β |

| Control: Gender | (−)0.064 | (−)0.074 | (−)0.074 |

| Control: Age Group 20s | 0.172 | 0.066 | 0.014 |

| Control: Age Group 30s | 0.252 | 0.117 | 0.056 |

| Control: Age Group 40s | 0.224 | 0.126 | 0.078 |

| Control: Gender × Organic JAS Label Awareness | (−)0.007 | (−)0.010 | (−)0.006 |

| Organic JAS Label Awareness | 0.523 *** | 0.436 *** | 0.439 *** |

| RSPO Label Awareness | 0.312 *** | 0.290 *** | |

| Moderation: Organic JAS label Awareness × RSPO Label Awareness | (−)0.103 ** | ||

| R2 | 0.287 | 0.375 | 0.386 |

| ΔR2 | 0.89 | 0.010 | |

| F | 33.34 *** | 42.68 *** | 38.90 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Natsir, S.A.; Takai, A.; Seo, E.; Seo, G.-H.; Kim, J. How Awareness of Organic JAS and RSPO Labels Influences Japanese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay More for Organic Cosmetics. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167466

Natsir SA, Takai A, Seo E, Seo G-H, Kim J. How Awareness of Organic JAS and RSPO Labels Influences Japanese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay More for Organic Cosmetics. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167466

Chicago/Turabian StyleNatsir, Sherry Adelia, Aiko Takai, Eunji Seo, Gang-Hoon Seo, and Jaewook Kim. 2025. "How Awareness of Organic JAS and RSPO Labels Influences Japanese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay More for Organic Cosmetics" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167466

APA StyleNatsir, S. A., Takai, A., Seo, E., Seo, G.-H., & Kim, J. (2025). How Awareness of Organic JAS and RSPO Labels Influences Japanese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay More for Organic Cosmetics. Sustainability, 17(16), 7466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167466