Does Local Government Debt Reduce Urban Economic Inequality? Evidence from Chinese Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

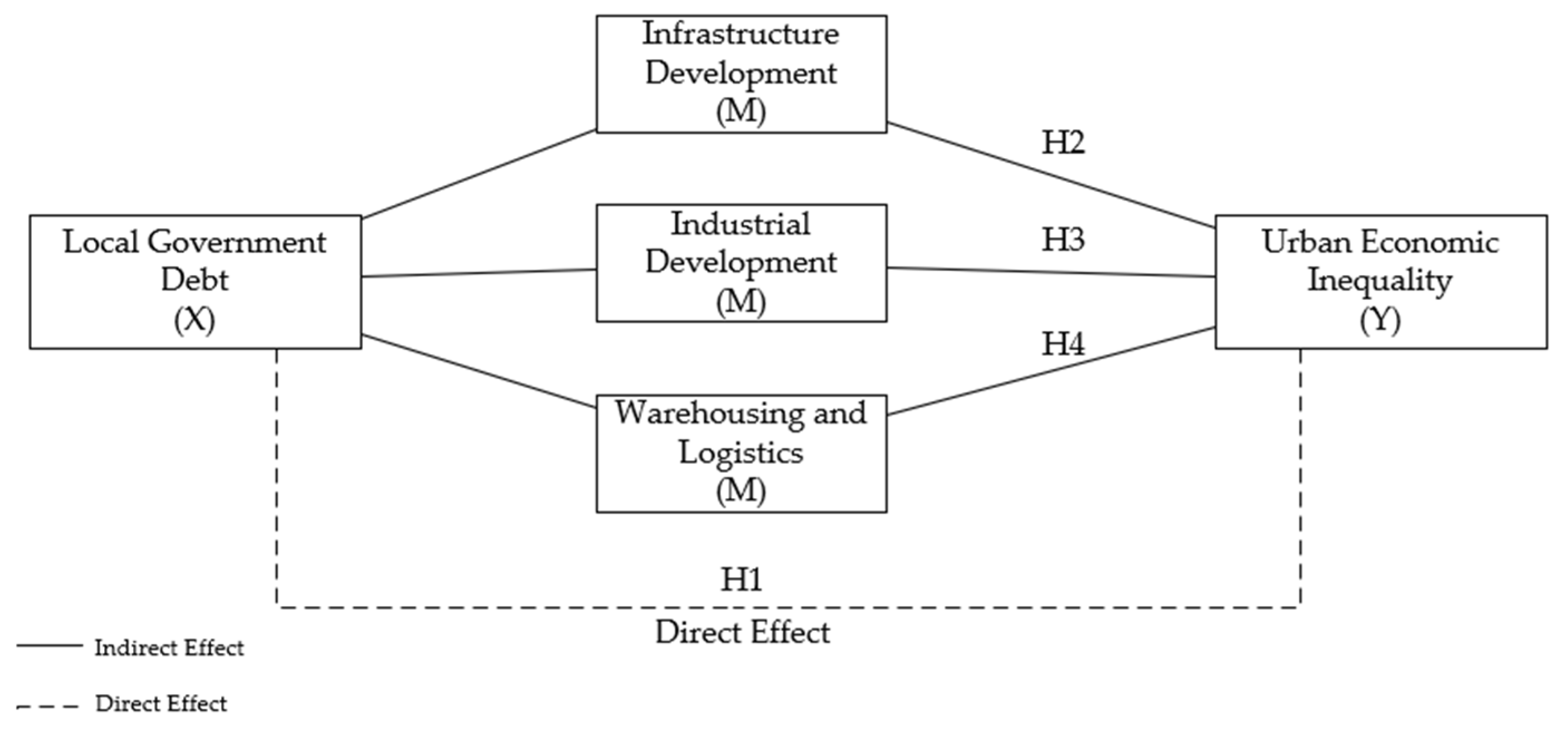

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Local Government Debt and Regional Economic Inequality

2.2. Infrastructure Development as a Mediating Mechanism

2.3. Industrial Development as a Mediating Mechanism

2.4. Warehousing and Logistics Infrastructure as a Mediating Mechanism

3. Research Design

3.1. Dependent Variables

3.2. Independent Variable

3.3. Control Variables

4. Empirical Results

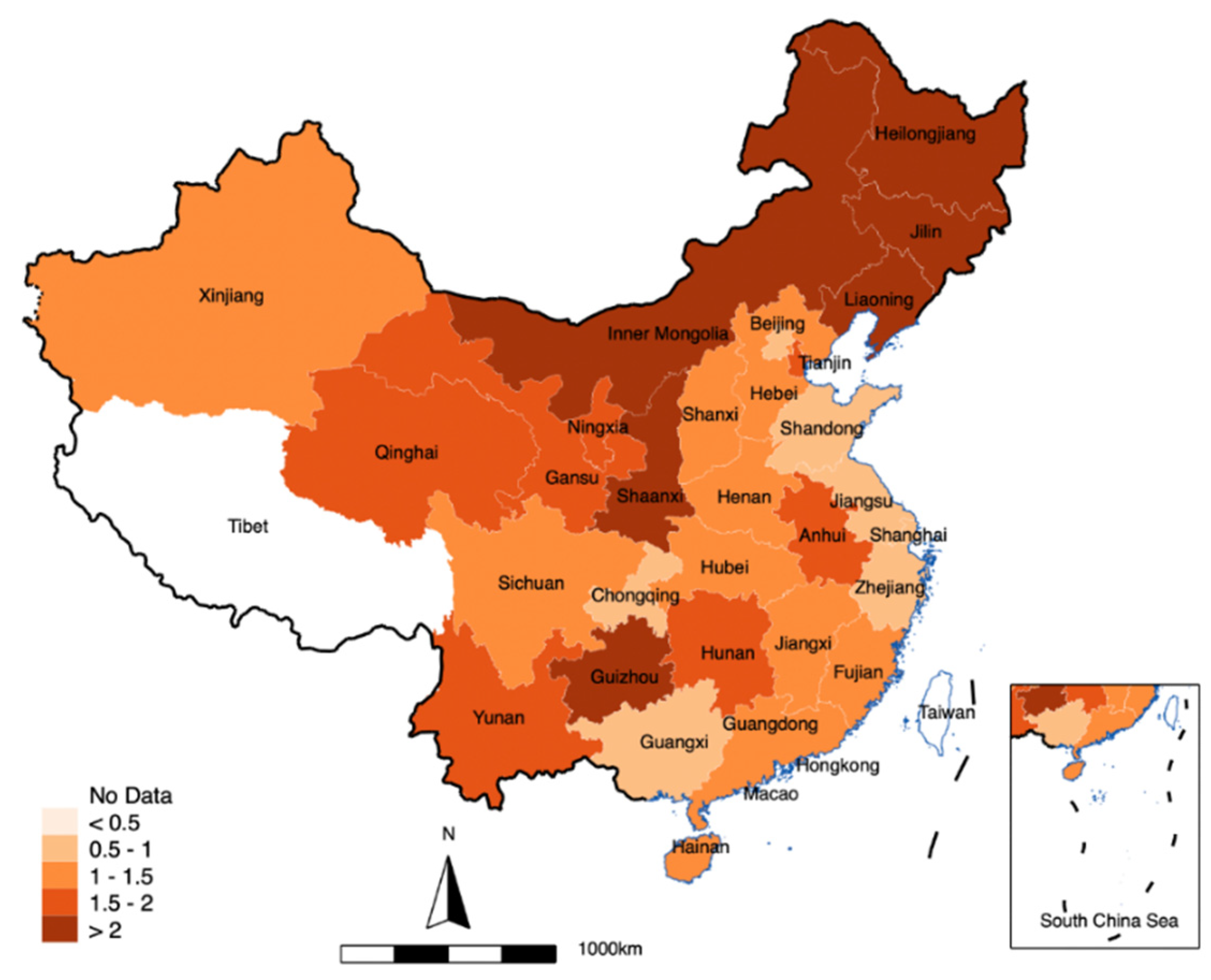

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.2. Regression Analysis

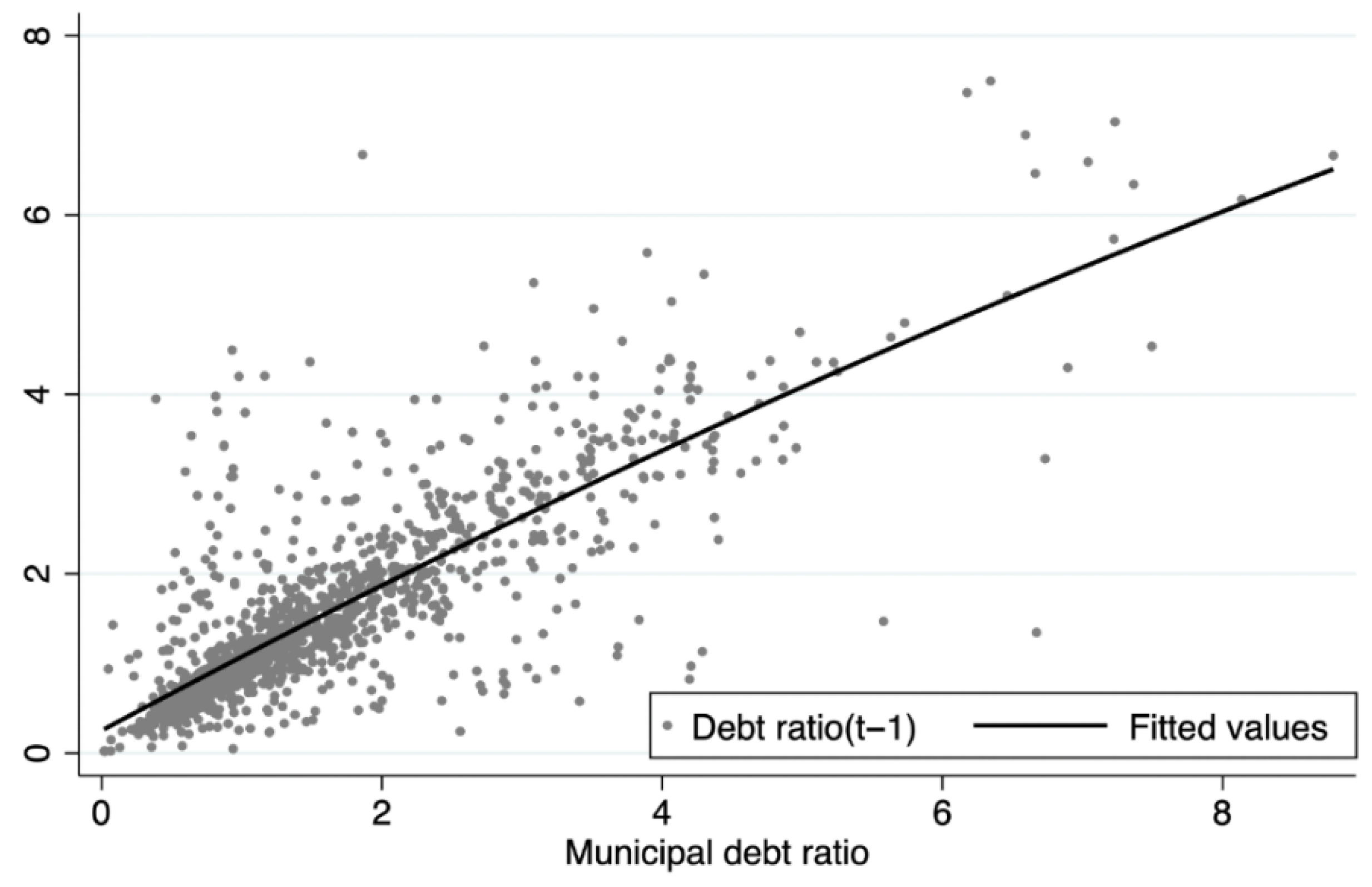

4.3. Instrumental Variable Estimation

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5. Mechanism Analysis Result

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Independent Variable | Gini Coefficient (Nighttime Light Intensity) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Local Government Debt Ratio | −0.00438 *** (0.00118) | −0.00342 *** (0.00132) | −0.00334 *** (0.00059) |

| Debtt−1 | −0.00348 ** (0.00125) | −0.00289 *** (0.00054) | |

| Debtt−2 | −0.00197 *** (0.00048) | ||

| Individual Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y |

| Time Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | 0.52822 *** (0.1201) | 0.49169 *** (0.1272) | 0.65891 *** (0.06567) |

| Year | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 |

| Observations | 1680 | 1362 | 1082 |

| R2 | 0.0880 | 0.1052 | 0.2982 |

References

- Bulman, D.J.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Q. Picking Losers: How Career Incentives Undermine Industrial Policy in Chinese Cities. J. Dev. Stud. 2022, 58, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirson, H.; Ricci, L.A.; Pattillo, C.A. What Are the Channels Through Which External Debt Affects Growth? IMF Working Paper; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, A.; Checherita-Westphal, C.; Rother, P. Debt and Growth: New Evidence for the Euro Area. J. Int. Money Financ. 2013, 32, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, U.; Sturzenegger, F.; Zettelmeyer, J. The Economics and Law of Sovereign Debt and Default. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 651–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, C.M.; Rogoff, K.S.; Savastano, M.A. Debt Intolerance; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgulu, N.; Foster, V.; Rana, A. Understanding Public Spending Trends for Infrastructure in Developing Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Callen, T.; Terrones, M.; Debrun, X.; Daniel, J.; Allard, C. Chapter III: Public Debt in Emerging Markets: Is It Too High? International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. Towards Equitable and Sustainable Urban Space: Introduction to Special Issue on “Urban Land and Sustainable Development”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality, 1st ed.; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-393-34506-3. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, F.H.; Wei, Y.D. Space, Scale, and Regional Inequality in Provincial China: A Spatial Filtering Approach. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 61, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Rodrik, D. Distributive Politics and Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, T.; Tabellini, G. Is Inequality Harmful for Growth? Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 600–621. [Google Scholar]

- Haggard, S.; Kaufman, R.R. Inequality and Regime Change: Democratic Transitions and the Stability of Democratic Rule. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 106, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, F. Does Economic Inequality Depress Electoral Participation? Testing the Schattschneider Hypothesis. Political Behav. 2010, 32, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelson, G.M.; Gonzalez, A.; Peterson, G.D. Economic Inequality Predicts Biodiversity Loss. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Pan, S.; Yao, X. Regional Convergence and Sustainable Development in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zou, H. Regional Inequality in Contemporary China. Ann. Econ. Financ. 2012, 13, 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kanbur, R.; Fan, S.; Zhang, X. China’s Regional Disparities: Experience and Policy. Rev. Dev. Financ. 2011, 1, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, L.; Yao, H.; Mear, F.C. New Development: Is China’s Local Government Debt Problem Getting Better or Worse? Public Money Manag. 2021, 41, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Wu, S.; Huang, P. Crowding out or crowding in: How does local government debt affect corporate green investment. J. Financ. Econ. Res. 2025, 40, 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell, S.; Mark, S.; LaVelle, M.; Parker, A. Union Rights and Inequalities. Hum. Rights Rev. 2023, 24, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederman, L.-E.; Gleditsch, K.S.; Buhaug, H. Inequality, Grievances, and Civil War; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-107-01742-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ostby, G. Polarization, Horizontal Inequalities and Violent Civil Conflict. J. Peace Res. 2008, 45, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, F. Policies towards Horizontal Inequalities in Post-Conflict Reconstruction. In Making Peace Work; Studies in Development Economics and Policy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2008; pp. 136–174. ISBN 978-0-230-22245-8. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, P.A. National debt in a neoclassical growth model. Am. Econ. Rev. 1965, 55, 1126–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Grobéty, M. Government Debt and Growth: The Role of Liquidity. J. Int. Money Financ. 2018, 83, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Moll de Alba, J.; Liew, K.-H. Debt and Economic Growth in Asian Developing Countries. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Paul, G. Fiscal Policy in an Endogenous Growth Model. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 1243–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.; Gregory, M. Government Debt. In Handbook of Macroeconomics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 1615–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, C.M.; Rogoff, K.S. Growth in a Time of Debt. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchetti, S.G.; Mohanty, M.S.; Zampolli, F. The Real Effects of Debt 2011; Bank for International Settlements: Basel, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Panizza, U.; Presbitero, A.F. Public Debt and Economic Growth in Advanced Economies: A Survey. Schweiz. Z. Volkswirtsch. Stat. 2013, 149, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W. Study on the nonlinear relationship between local government debt and regional economic growth in China. J. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2014, 189, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J. Analysis of the Impact of Local Debt on Economic Growth: From a Liquidity Perspective. J. Chin. Ind. Econ. 2015, 11, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, G.S. Data for Measuring Poverty and Inequality Changes in the Developing Countries. J. Dev. Econ. 1994, 44, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.V.; Storeygard, A.; Weil, D.N. Measuring Economic Growth from Outer Space. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 994–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.; Wills, S. Left in the Dark? Oil and Rural Poverty. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 5, 865–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.U.; Xu, C.; Bavel, B.V.; Van Nes, E.H.; Scheffer, M. Global Inequality Remotely Sensed. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e1919913118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Turnovsky, S.J. Infrastructure and Inequality. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2012, 56, 1730–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Jalles D’Orey, M.A.; Duvendack, M.; Esposito, L. Does Government Spending Affect Income Inequality?: A Meta-Regression Analysis. J. Econ. Surv. 2017, 31, 961–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokan, Y.; Turnovsky, S.J. Taylor Rules: Consequences for Wealth and Income Inequality. J. Macroecon. 2023, 77, 103544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, E.N.; Zacharias, A. THE Distributional Consequences of Government Spending and Taxation in the U.S., 1989 and 2000. Rev. Income Wealth 2007, 53, 692–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, L.; Sousa, R.M. How Does Fiscal Consolidation Impact on Income Inequality? Rev. Income Wealth 2014, 60, 702–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Kanbur, S.M.R. The Kuznets Process and the Inequality—Development Relationship. J. Dev. Econ. 1993, 40, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, A.; Sakutukwa, T.; Dzhumashev, R. Long-Term Determinants of Income Inequality: Evidence from Panel Data over 1870–2016. Empir. Econ. 2021, 61, 1935–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.H.; Richard, S.F. Tests of a Rational Theory of the Size of Government. Public Choice 1983, 41, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Research on income growth effects and distribution effects of local government debt: Evidence from China. Contemp. Financ. Econ. 2018, 403, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yang, C. Income distribution effects of public debt: Theoretical mechanisms and empirical tests—Evidence from cross-national panel data. Public Financ. Res. 2019, 2, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Chen, Z. Economic growth, income distribution and Chinese government debt risk. Econ. Surv. 2020, 37, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yin, P. Research on income distribution effects of local government debt in China. J. Financ. Res. 2019, 11, 86–97,123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, S. Construction and practice of ex-ante performance evaluation index system for local government special bonds: An empirical analysis based on 105 major projects in Guangdong Province. Sub Natl. Fisc. Res. 2024, 6, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, F.; Tian, G.; Xiao, H. The Impact and Mechanism of Infrastructure on China’s Economic Growth: An Analysis Based on the Extended Barro Growth Model. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2020, 40, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Somanathan, R. The Political Economy of Public Goods: Some Evidence from India. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 82, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, C.; Servén, L. The Effects of Infrastructure Development on Growth and Income Distribution; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Besant-Jones, J.E.; Estache, A.; Ingram, G.K.; Kessides, C.F.; Lanjouw, P.F.; Mody, A.; Pritchett, L.H. World Development Report: Infrastructure for Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Estache, A. On Latin America’s Infrastructure Privatization and Its Distributional Effects; SSRN: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Estache, A.; Foster, V.; Wodon, Q. Accounting for Poverty in Infrastructure Reform: Learning from Latin America’s Experience; WBI Development Studies; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-8213-5039-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rammelt, C. Infrastructures as Catalysts: Precipitating Uneven Patterns of Development from Large-Scale Infrastructure Investments. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S.R.; Bakht, Z.; Koolwal, G.B. The Poverty Impact of Rural Roads: Evidence from Bangladesh. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2009, 57, 685–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Liu, J.; Mao, J. The investment-driven effect of special-purpose bonds for industrial parks: From the perspective of enterprise entry. Nankai Econ. Stud. 2025, 4, 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. Government Behavior and Industrial Structure Evolution: An Investigation from the Perspective of Fixed Asset Investment. Contemp. Chin. Hist. Stud. 2014, 21, 32–42+125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C. Current problems in China’s industrial development and countermeasures for future high-quality development. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 19, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Leapfrog Development in Underdeveloped Agricultural Regions Amidst Industrialization: Insights from the Agricultural Transformation of Agro-Pastoral Ecotones. Soc. Sci. China 2025, 3, 22–41+204–205. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.; Liu, C.; Xin, X. China’s Industrialization: Past and Present (1887–2017). China J. Econ. 2020, 7, 202–238. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. The goal of common prosperity and the choice of paths to achieve it. Econ. Res. J. 2021, 56, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, G. High-quality development of manufacturing industry and common prosperity. J. Yantai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 37, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, E. The target risks and countermeasures of local government special-purpose bonds. Sub Natl. Fisc. Res. 2021, 4, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wu, Y. Impact of digital logistics parks on high-quality development of urban economy—An empirical analysis based on DID method. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 25, 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, W. The impact of the development of circulation industry in western ethnic minority areas on the urban-rural income gap. J. Mod. Bus. 2023, 7, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Zhu, Y. The impact of industry upgrading on labor employment. J. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2019, 38, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y. Fairness and influencing factors of regional logistics resource allocation: A case study of Sichuan Province. China Bus. Mark. 2016, 30, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, T. The Role of E-Commerce in Promoting Sustainable Local Employment in Rural Areas: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, N. E-commerce and the Development of Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives: Evidence from “E-commerce into Rural Areas Demonstration Counties”. Nankai Econ. Stud. 2025, 2, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Liu, M. Fiscal Dependency and Rural Revitalization: Empirical Evidence from Chinese County-Level Panel Data. J. Contemp. Econ. Res. 2025, 5, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Cheng, S.; Zhuang, Y. How e-commerce in villages empowers rural revitalization: A quasi-natural experiment based on the “e-commerce in villages demonstration county”. J. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2025, 3, 172–190. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, J.; Jiang, L. Characteristics and Mechanism Identification of Platform Economy’s Impact on Urban-Rural Income Disparity. J. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Gao, X. Impact Analysis of Platform Economy on Rural E-commerce Entrepreneurship. J. Commer. Econmics 2024, 19, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Xiong, L.; Wang, L. Mapping Regional Economic Activity Using DMSP/OLS Nighttime Light Data. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2020, 5, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Nordhaus, W.D. Using Luminosity Data as a Proxy for Economic Statistics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8589–8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltagi, B.H. Forecasting with Panel Data. J. Forecast. 2008, 27, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, W. Econometric Analysis of Cross-Section and Panel Data, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Tian, Y.; Lei, A.; Boadu, F.; Ren, Z. The Effect of Local Government Debt on Regional Economic Growth in China: A Nonlinear Relationship Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Song, X. Analyzing the Mechanism Between Local Government Debts and China’s Economic Development: Spatial Spillover Effects and Environmental Consequences. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 928975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesch, K.; Hauser, O.P.; Jachimowicz, J.M. Measuring Inequality beyond the Gini Coefficient May Clarify Conflicting Findings. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2016: Taking on Inequality; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, F.H.G.; Lustig, N.; Teles, D. Appraising Cross-National Income Inequality Databases: An Introduction. J. Econ. Inequal. 2015, 13, 497–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, S.; Qian, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Wu, J. An Extended Time Series (2000–2018) of Global NPP-VIIRS-like Nighttime Light Data from a Cross-Sensor Calibration. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.V.; Squires, T.; Storeygard, A.; Weil, D. The Global Distribution of Economic Activity: Nature, History, and Thhe Role of Trade. Q. J. Econ. 2018, 133, 357–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, D.; Stewart, B. Nighttime Lights Revisited: The Use of Nighttime Lights Data as a Proxy for Economic Variables; Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Local debt expansion and corporate tax avoidance: An empirical study based on the prefecture-level. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2021, 8, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, S.; Wang, X. Soft budget constraints on local government debt under the new Budget Law: Calculation based on the transaction data of “self-insurance and self-repayment” debt. J. Econ. Rev. 2021, 5, 136–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Pan, Y. Can the issuance of local government bonds promote the high-quality development of real enterprises?—An empirical study based on the data of China’s A-share and NEEQ manufacturing listed companies. J. Tech. Econ. 2023, 42, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, W. Assessment of China’s Local Government Debt Transparency: 2014–2015. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2017, 19, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfatti, A.; Forni, L. Fiscal Rules to Tame the Political Budget Cycle: Evidence from Italian Municipalities. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2019, 60, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Kong, F. Policy Innovation of Local Officials in China: The Administrative Choice. Chin. J. Political Sci. 2021, 26, 695–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, Y. Term Limits and Rotation of Chinese Governors: Do They Matter to Economic Growth? Econ. Res. J. 2007, 11, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.-A. Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 1743–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Shu, Y. Local Officials and Economic Growth. Econ. Res. J. 2007, 9, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, J.L.; MacKinnon, D.P. Multilevel Modeling of Individual and Group Level Mediated Effects. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2001, 36, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baret, M.; Menuet, M. Fiscal and Environmental Sustainability: Is Public Debt Environmentally Friendly? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 87, 1497–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, H.; Kwakwa, P.A. The Effect of Natural Resources Extraction and Public Debt on Environmental Sustainability. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2023, 34, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, K.C.; Digiuseppe, M.R. The Physical Consequences of Fiscal Flexibility: Sovereign Credit and Physical Integrity Rights. Br. J. Political Sci. 2017, 47, 783–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Label | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||

| Gini coefficient | Gini | |

| Independent Variable | ||

| Local government debt ratio | Debt | Total debt outstanding divided by comprehensive fiscal capacity |

| Control Variables | ||

| Industrialization level | Indl | The ratio of industrial added value to gross regional product |

| Internet penetration rate | Inte | Number of internet users per hundred people |

| Education level | Edu | Number of students enrolled in higher education institutions/total population at the end of the year |

| Environmental regulation | Env | Comprehensive utilization rate of general industrial solid waste |

| Extent of unemployment | Unem | Number of individuals enrolled in unemployment insurance |

| Average house price | Hous | Average residential property prices |

| Urbanization level | Urban | Urban population/Total population |

| GDP per capita | GDP | Log GDP per capita |

| Instrumental Variables | ||

| Administration cycle | Adm | Mayor’s term duration |

| Lagged debt ratio | Lag | Debtt−1 |

| Mechanism Analysis | ||

| Infrastructure Development | Infc | Per Capita Road Area (Unit in square meters) |

| Industrial Development | Indc | Value Added of the Tertiary Industry/Value Added of the Secondary Industry |

| Warehousing and Logistics Construction | Ware | Total Freight Volume (Including Civil Aviation Freight, Waterway Freight, Railway Freight, and Highway Freight, unit in 10,000 tons) |

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||||

| Gini coefficient | 0.622 | 0.164 | 0.024 | 0.905 | a |

| Independent Variable | |||||

| Local government debt ratio | 1.551 | 1.142 | 0.018 | 8.789 | b |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Industrialization level (Log) | 0.311 | 0.096 | 0.097 | 0.693 | c |

| Internet penetration rate (Log) | 3.271 | 0.424 | 2.211 | 4.433 | d |

| Education level (Log) | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.125 | d |

| Environmental regulation (Log) | 4.28 | 0.493 | 0.215 | 4.902 | c |

| Extent of unemployment (Log) | 12.701 | 1.013 | 8.294 | 16.395 | c |

| Average house price (Log) | 8.795 | 0.492 | 7.466 | 10.997 | e |

| Urbanization level (Log) | 1.895 | 0.165 | 0.521 | 2.178 | c |

| GDP per capita (Log) | 10.844 | 0.525 | 9.304 | 12.281 | c |

| Instrumental Variables | |||||

| Administration cycle | 2.502 | 1.362 | 1 | 5 | f |

| Lagged debt ratio | 1.505 | 1.087 | 0.018 | 7.494 | a |

| Mechanism Analysis | |||||

| Infrastructure Development (Log) | 2.930 | 0.362 | 1.335 | 4.071 | c |

| Industrial Development (Log) | 0.745 | 0.220 | 0.302 | 1.848 | c |

| Warehousing and Logistics Construction (Log) | 9.397 | 1.426 | 0 | 13.512 | c |

| Independent Variable | Gini Coefficient (Nighttime Light Intensity) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Local Government Debt Ratio | −0.00567 *** (0.00111) | −0.00684 *** (0.00112) | −0.00616 *** (0.00112) | −0.00438 *** (0.00118) |

| Individual Fixed Effects | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Time Fixed Effects | N | N | Y | Y |

| Control Variables | N | N | N | Y |

| Constant | 0.6309 *** (0.0094) | 0.63241 (0.0019) | 0.63394 *** (0.0023) | 0.52822 *** (0.1201) |

| Year | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 |

| Observations | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 |

| R2 | 0.0244 | 0.0261 | 0.0285 | 0.0880 |

| Indipendent Variable | Administration Cycle | Lagged Debt Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Instrumental variables | −0.0645 *** (0.021) | −0.0754 *** (0.019) | 0.2898 *** (0.027) | 0.2778 *** (0.0274) |

| Constant | 1.666 *** (0.087) | 11.649 *** (0.541) | 2.9207 *** (0.261) | 9.2458 *** (2.162) |

| Control variables | N | Y | N | Y |

| Year fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual fixed effects | N | N | Y | Y |

| R-squared | 0.0149 | 0.2253 | 0.8143 | 0.8196 |

| Independent Variable | Administration Cycle Model | Lagged Debt Ratio Model |

|---|---|---|

| (5) | (6) | |

| Local government debt ratio | −0.074 ** (0.036) | −0.0197 *** (0.004) |

| Constant | 3.157 *** (0.427) | 0.711 *** (0.098) |

| Control variables | Y | Y |

| Year fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Individual fixed effects | N | Y |

| Cragg–Donald Wald F-statistic | 16.443 | 102.585 |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | |

| R-squared | 0.1717 | 0.9813 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern China | Northeastern China | Central China | Western China | |

| Local Government Debt Ratio | −0.00462 (0.00479) | −0.00466 *** (0.0092) | −0.00330 ** (0.00150) | −0.00522 *** (0.00100) |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −1.80685 *** (1.43755) | −0.42515 *** (0.33578) | −0.04114 *** (0.21320) | 0.77255 *** (0.12375) |

| Year | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 | 2015–2020 |

| Observations | 502 | 194 | 471 | 474 |

| R2 | 0.0944 | 0.5894 | 0.2151 | 0.2089 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infc | Gini | Indc | Gini | Ware | Gini | |

| Local Government Debt Ratio | 0.025 ** (0.016) | −0.004 *** (0.002) | 0.031 ** (0.017) | −0.004 *** (0.001) | 0.058 *** (0.025) | −0.004 *** (0.001) |

| Infrastructure Development (Log) | −0.017 ** (0.005) | |||||

| Industrial Development (Log) | −0.029 *** (0.002) | |||||

| Warehousing and Logistics Construction (Log) | −0.032 *** | |||||

| Individual fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | 1.163 * (0.641) | 0.541 *** (0.120) | 1.964 *** (0.351) | 0.585 *** (0.121) | 4.456 *** (2.493) | 0.528 *** (0.120) |

| Observations | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 |

| R2 | 0.252 | 0.103 | 0.566 | 0.112 | 0.131 | 0.139 |

| Mediator Variable | Indirect Effect | Direct Effect | Total Effect | Mediation Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure Development | −0.0004 | −0.004 | −0.0044 | 9.60% |

| Industrial Development | −0.0009 | −0.004 | −0.0049 | 18.35% |

| Warehousing and Logistics | −0.0019 | −0.004 | −0.0059 | 31.69% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, H.; Hu, Y. Does Local Government Debt Reduce Urban Economic Inequality? Evidence from Chinese Cities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167340

Lin H, Hu Y. Does Local Government Debt Reduce Urban Economic Inequality? Evidence from Chinese Cities. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167340

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Hongsheng, and Yingjia Hu. 2025. "Does Local Government Debt Reduce Urban Economic Inequality? Evidence from Chinese Cities" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167340

APA StyleLin, H., & Hu, Y. (2025). Does Local Government Debt Reduce Urban Economic Inequality? Evidence from Chinese Cities. Sustainability, 17(16), 7340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167340