Integrating Community Fabric and Cultural Values into Sustainable Landscape Planning: A Case Study on Heritage Revitalization in Selected Guangzhou Urban Villages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

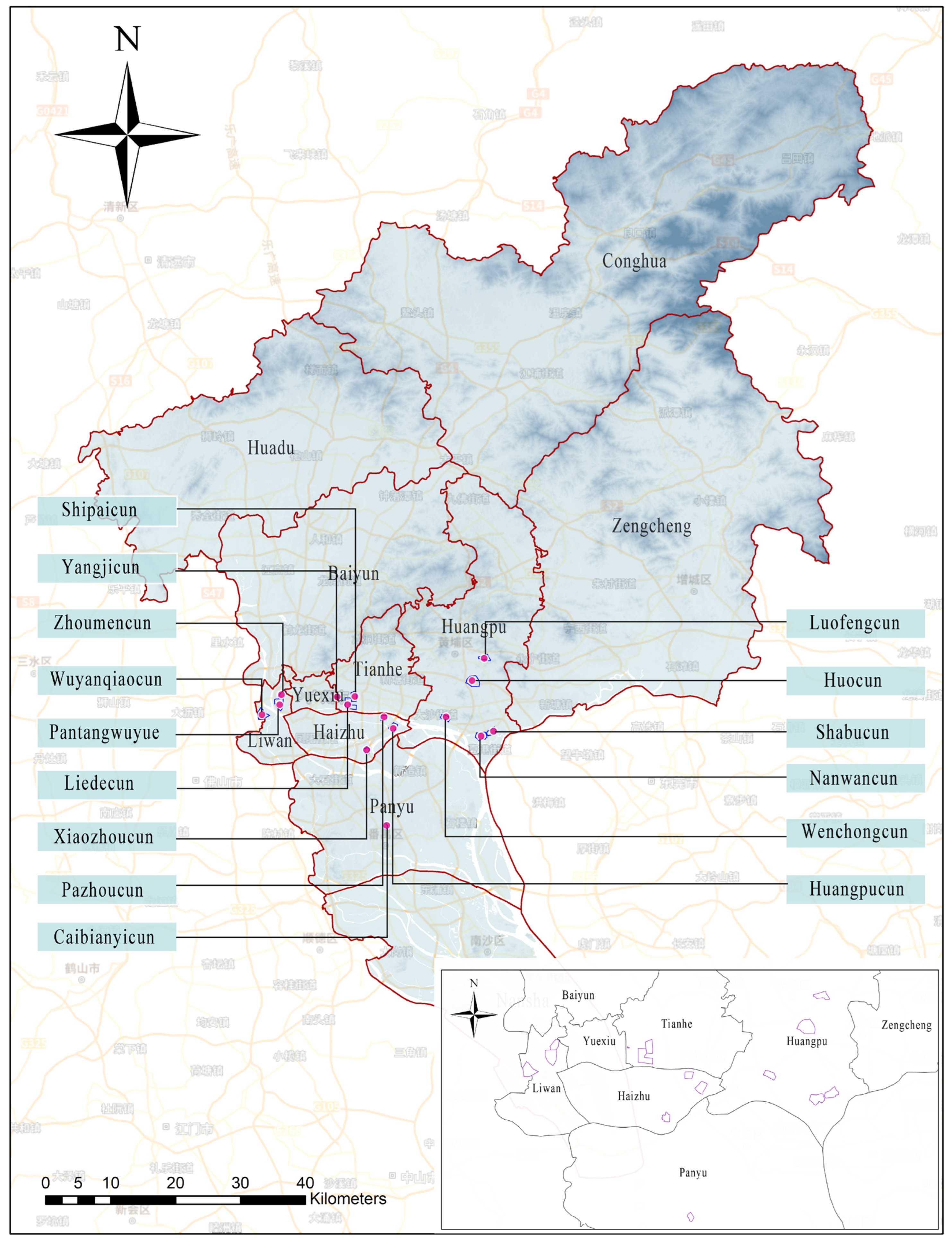

2.1. Research Area

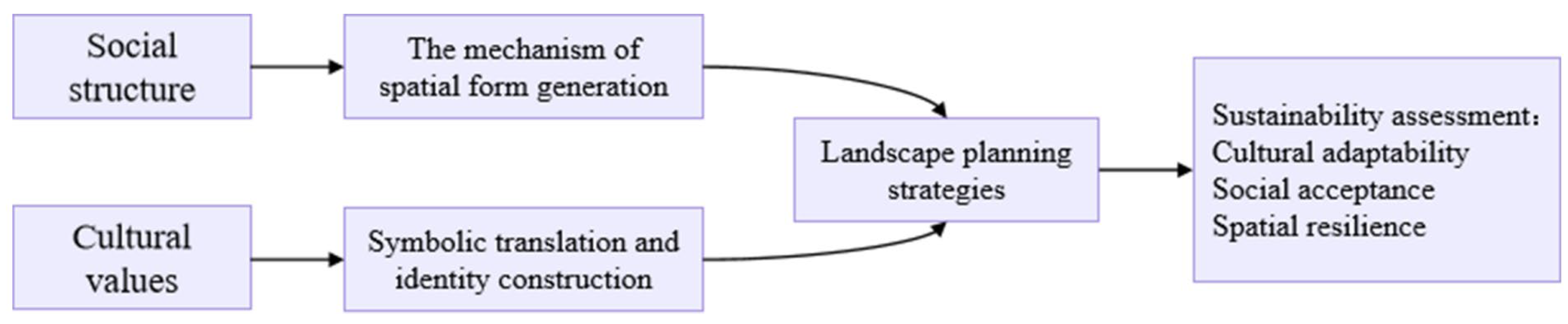

2.2. Research Framework

2.3. Research Methodology

2.3.1. Theoretical Framework for Adaptive Landscape Conservation in Sustainable Urban Transition

2.3.2. Sentiment-Informed Perception Assessment: A Semantic Analytical Framework for Web-Based Textual Data in Urban Contexts

2.3.3. Comparative Multi-Case Study Methodology

2.3.4. Urban Anthropological Field Research in Sustainable Development Contexts

2.3.5. Interdependence Analysis of Spatial Morphology and Functional Typologies in Urban Villages

2.3.6. Policy Discourse Analysis

2.3.7. Interdependence Analysis of Migrant Population Influx and Spatial Landscape Adaptability in Urban Villages

2.4. Source of Evidence (Data Collection Procedures for Case Studies)

3. Results

3.1. Social Acceptance

3.1.1. Emotional Orientation and Public Perception

3.1.2. The Coupling of Inflow of Population and Suitability of Urban Landscape

3.2. Drivers and Barriers

3.2.1. Spatial Form-Functional Form Synergy

3.2.2. The Perceptual Reinforcement Effect of Cultural Symbols

3.3. Emotional Orientation

4. Discussions

4.1. The Deep Impact of Community Social Structure on Spatial Governance

4.1.1. An Economy-Driven Social Network (Shipai Village)

4.1.2. Clan-Led Spatial Governance (Huangpu Ancient Village vs. Zhoumen Village)

4.2. The Relationship Between Cultural Adaptability and Community Cohesion

4.3. The Technical Path of Sustainable Landscape Planning: From “Spatial Transformation” to “Social-Spatial Collaborative Governance”

5. Conclusions

5.1. Systematic Element Classification and Typological Division Framework Taking Guangzhou Urban Village as an Example

5.2. The Relationship Between the Perceptual Reinforcement Effect of Cultural Symbols and Community Cohesion

5.3. Towards Socio-Spatial Synergistic Regeneration

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H. The role of informal ruralization within China’s rapid urbanization. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, C.; Lin, Y.; Li, Z.; Du, Q. Urban Morphology Promotes Urban Vibrancy from the Spatiotemporal and Synergetic Perspectives: A Case Study Using Multisource Data in Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bramwell, B. Heritage protection and tourism development priorities in Hangzhou, China: A political economy and governance perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızı, Ö.; Karaman, A. A participatory planning model in the context of Historic Urban Landscape: The case of Kyrenia’s Historic Port Area. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nello-Deakin, S. Is there such a thing as a ‘fair’ distribution of road space? J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viderman, T.; Geddes, I.; Psathiti, C. Lived Urban Form: Using Urban Morphology to Explore Social Dimensions of Urban Space. J. Public Space 2023, 8, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. (Ed.) CHAPTER 1—Urban Design as the Organization of Space, Time, Meaning and Communication. In Human Aspects of Urban Form; Elsevier: Pergamon, Turkey, 1977; pp. 8–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. A Global Sense of Place. Space Place Gend. 1991, 38, 166–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hilari, J.; Wehren, J. Social Choreography as a Cultural Commoning Practice: Becoming Part of Urban Transformation in Une danse ancienne. Arts 2024, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Changing neighbourhood cohesion under the impact of urban redevelopment: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, Y. The Renovation Scheme of Historical and Cultural Blocks in the City—Taking Yongqing Fang of Guangzhou as an Example. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2024, 35, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.A.O.; Mingyang, C.; Wenying, F.U. Reconstruction of Guangzhou urban villages’ traditional lineage culture in the context of rapid urbanization:From spatial form of ancestral hall to behavioral patterns of villagers. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2015, 70, 1987–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.G.; Lee, W.H.H.; Tang, B.M.; Chen, Z. Legacy of culture heritage building revitalization: Place attachment and culture identity. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1314223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alumäe, H.; Printsmann, A.; Palang, H. Cultural and Historical Values in Landscape Planning: Locals’ Perception. In Landscape Interfaces: Cultural Heritage in Changing Landscapes; Palang, H., Fry, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, J.; Vinodhini, O. Recording and Conceptualising Cultural Values in Landscape: The Travelling Transect-based Drawing approach. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, England, 2023; Volume 1210, p. 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y. (Eds.) Urban Morphology and Historical Urban Landscape Conservation and Management. In Conserving and Managing Historical Urban Landscape: An Integrated Morphological Approach; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tara, A.; Lawson, G.; Davies, W.; Chenoweth, A.; Pratten, G. Integrating Landscape Character Assessment with Community Values in a Scenic Evaluation Methodology for Regional Landscape Planning. Land 2024, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nes, A.; Yamu, C. (Eds.) Established Urban Research Traditions and the Platform for Space Syntax. In Introduction to Space Syntax in Urban Studies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, A.N.; Biljecki, F. Classification of urban morphology with deep learning: Application on urban vitality. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 90, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zlatanova, S.; Cheng, S. Quantitative Analysis Method of the Organizational Characteristics and Typical Types of Landscape Spatial Sequences Applied with a 3D Point Cloud Model. Land 2024, 13, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Lin, J.; Li, X.; Wu, F. Redevelopment of urban village in China—A step towards an effective urban policy? A case study of Liede village in Guangzhou. Habitat Int. 2014, 43, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. Why can’t we be friends? The underlying hierarchy of social connections between diverse neighborhoods. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2022, 15, 1339–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.F.; Yan, C. Community Meta-Box: A Deployable Micro Space for New Publicness in High-Density City. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2023, 9, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andress, L.; Hall, T.; Davis, S.; Levine, J.; Cripps, K.; Guinn, D. Addressing power dynamics in community-engaged research partnerships. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2020, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, M.; He, S. Social mix and subjective wellbeing in Chinese urban neighborhoods: Exploring the domino effects of social capital through multilevel serial mediation analysis. Habitat Int. 2024, 143, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Fu, Y. Tripartite Evolutionary Game and Policy Simulation: Strategic Governance in the Redevelopment of the Urban Village in Guangzhou. Land 2024, 13, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hamilton, W.L.; Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, C.; Jurafsky, D.; Leskovec, J. Community Identity and User Engagement in a Multi-Community Landscape. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Weblogs Soc. Media 2017, 2017, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, B.; Tong, D.; Que, J.; Peng, H. Planner-led collaborative governance and the urban form of urban villages in redevelopment: The case of Yangji Village in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2023, 142, 104521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, J. Cultural reinvention or cultural erasure? A study on rural gentrification, land leasing, and cultural change. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zou, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, L. Constructing an ideal home: Affective atmosphere creation as a public participation strategy for urban village renovation. Cities 2024, 146, 104777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Xue, D.; Yu, Y. Reconfiguration of Cultural Resources for Tourism in Urban Villages—A Case Study of Huangpu Ancient Village in Guangzhou. Land 2022, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi, A.; Allam, Z.; Siew, G. (Eds.) Diversity in Cities and Addressing Urban Sustainability. In Diversity as Catalyst: Economic Growth and Urban Resilience in Global Cityscapes; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Meulder, B.D.; Wang, S. From village to metropolis: A case of morphological transformation in Guangzhou, China. Urban Morphol. 2010, 15, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. (Ed.) The Social Stratification Structures in the Urban Villages: The Established and the Generated. In Urban Village Renovation: The Stories of Yangcheng Village; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; He, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, W. Evaluating residents’ satisfaction with market-oriented urban village transformation: A case study of Yangji Village in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2019, 95, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, E.; Özköse, A.; Heyik, M. Sustainable Heritage Planning for Urban Mass Tourism and Rural Abandonment: An Integrated Approach to the Safranbolu—Amasra Eco-Cultural Route. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Bohua, L.; Yindi, D.; Peilin, L. The Adjustment Process and Integration Path of Cultural Adaptation of Tourism-Driven Traditional Village Residents. Trop. Geogr. 2024, 44, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filepné Kovács, K.; Varga, D.; Kukulska-Kozieł, A.; Cegielska, K.; Noszczyk, T.; Husar, M.; Iváncsics, V.; Ondrejicka, V.; Valánszki, I. Policy instruments as a trigger for urban sprawl deceleration: Monitoring the stability and transformations of green areas. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, G.; Liao, L.; Xiong, L.; Zhu, B.-W.; Cheung, S.M. Revitalization and Development Strategies of Fostering Urban Cultural Heritage Villages: A Quantitative Analysis Integrating Expert and Local Resident Opinions. Systems 2022, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Ye, S. Rural settlement of urban dwellers in China: Community integration and spatial restructuring. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, T.; Fukuda, H. Adaptation Analysis of Urban Village Resettlers Based on Lefebvre’s Spatial Production Theory in Qingdao, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; van Oostrum, M. The self-governing redevelopment approach of Maquanying: Incremental socio-spatial transformation in one of Beijing’s urban villages. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.A.A.; Al-Hinkawi, W.S.; Sherzad, M.F. Adaptive Flexibility of the City’s Complex Systems. Buildings 2024, 14, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, S.; Wu, X.; Xia, X. Cultural landscape perception of the Chinese traditional settlement: Based on tourists’ online comments. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z. Research on Rural Landscape Preference Based on TikTok Short Video Content and User Comments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, L. Spatial Coupling Coordination Evaluation of Mixed Land Use and Urban Vitality in Major Cities in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delso, J.; Martín, B.; Ortega, E. A new procedure using network analysis and kernel density estimations to evaluate the effect of urban configurations on pedestrian mobility. The case study of Vitoria—Gasteiz. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 67, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Wu, X.; Hou, Q. Optimization of urban village public space vitality based on complex network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Szabó, G. Multi-objective urban land use optimization using spatial data: A systematic review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codosero Rodas, J.M.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Castanho, R.A.; Cabezas, J. Land Valuation Sustainable Model of Urban Planning Development: A Case Study in Badajoz, Spain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Jia, K. How rent facilitates capital accumulation: A case study of rural land capitalization in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 139, 107063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Ge, D.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, Y. Rural revitalization mechanism based on spatial governance in China: A perspective on development rights. Habitat Int. 2024, 147, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gao, W.; Yang, F. Authenticity, Integrity, and Cultural—Ecological Adaptability in Heritage Conservation: A Practical Framework for Historic Urban Areas—A Case Study of Yicheng Ancient City, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Time rupture in urban heritage: Based on the case of shanghai. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Qian, Z. Villagers’ acculturation in China’s land expropriation-induced resettlement neighborhood: A Shanghai case. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 74, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.; Chan Albert, P.C. Revitalizing Historic Buildings through a Partnership Scheme: Innovative Form of Social Public—Private Partnership. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2014, 140, 04013005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Poortinga, W. Built environment, urban vitality and social cohesion: Do vibrant neighborhoods foster strong communities? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qu, F. Preserving Authenticity in Urban Regeneration: A Framework for the New Definition from the Perspective of Multi-Subject Stakeholders—A Case Study of Nantou in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, N.; Pop, A.-M.; Marian-Potra, A.-C. Culture-led urban regeneration in post-socialist cities: From decadent spaces towards creative initiatives. Cities 2025, 158, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, T.S.; Singh Srai, J.; Kumar, M.; Wohlrab, J. Identifying design criteria for urban system ‘last-mile’ solutions—A multi-stakeholder perspective. Prod. Plan. Control 2016, 27, 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevoets, B.; Sowińska-Heim, J. Community initiatives as a catalyst for regeneration of heritage sites: Vernacular transformation and its influence on the formal adaptive reuse practice. Cities 2018, 78, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Li, P.; Li, N. Deciphering Socio-Spatial Integration Governance of Community Regeneration: A Multi-Dimensional Evaluation Using GBDT and MGWR to Address Non-Linear Dynamics and Spatial Heterogeneity in Life Satisfaction and Spatial Quality. Buildings 2025, 15, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Standardized Rate of Inflow of Foreign Population | Comprehensive Index of Landform Suitability | Coupling Coordination Index | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wuyanqiao Village | 1 | 0.5014 | 0.7507 |

| Pantang Wuyue | 0.7158 | 0.4395 | 0.5777 |

| Xijiao Zhoumen | 0.3611 | 0.34498 | 0.353 |

| Shipai Village | 0.1 | 0.2976 | 0.1988 |

| Huangpu Village | 0.855 | 0.5653 | 0.7102 |

| Xiaozhou Village | 0.5875 | 0.4505 | 0.519 |

| Value Range | 0 | (0, 0.3] | (0.3, 0.5] | (0.5, 0.8] | (0.8, 1] | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coupling degree | Uncoupled | Low coupling | Moderate coupling | Benign coupling | High coupling | Fully coupled |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, H. Integrating Community Fabric and Cultural Values into Sustainable Landscape Planning: A Case Study on Heritage Revitalization in Selected Guangzhou Urban Villages. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167327

Li J, Zhang Y, Jin H. Integrating Community Fabric and Cultural Values into Sustainable Landscape Planning: A Case Study on Heritage Revitalization in Selected Guangzhou Urban Villages. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167327

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jianjun, Yilei Zhang, and He Jin. 2025. "Integrating Community Fabric and Cultural Values into Sustainable Landscape Planning: A Case Study on Heritage Revitalization in Selected Guangzhou Urban Villages" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167327

APA StyleLi, J., Zhang, Y., & Jin, H. (2025). Integrating Community Fabric and Cultural Values into Sustainable Landscape Planning: A Case Study on Heritage Revitalization in Selected Guangzhou Urban Villages. Sustainability, 17(16), 7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167327