1. Introduction

Digital transformation has become a critical driver of structural change and economic development in both developed and emerging economies. Defined as the integration of digital technologies into business processes, it reshapes traditional industrial structures, enables new forms of competition, and creates opportunities for innovation, operational efficiency, and improved financial performance [

1]. In developing economies, it also offers a pathway to leapfrogging traditional stages of industrialization by reconfiguring production and value creation processes. Technologies such as cloud computing, e-commerce platforms, and supply chain management systems increasingly influence the distribution of economic power across firms and regions, with significant implications for productivity, competitiveness, and inclusive growth [

2]. However, the uneven adoption of digital technologies risks reinforcing disparities between digitally advanced and lagging firms, particularly where access to infrastructure and digital literacy is limited. From an organizational economics perspective, digital transformation enables firms to mobilize and reconfigure resources, fostering adaptive capacity and resilience in volatile environments—capabilities emphasized in the Resource-Based View (RBV) [

3,

4] and the Dynamic Capabilities View (DCV) [

5]. In this context, digital transformation is increasingly recognized not only as a tool for firm-level efficiency, but also as a driver of sustainable industrial upgrading, regional equity, and inclusive growth [

6].

While digital transformation has gained prominence globally, its effects on firm performance remain complex and context-dependent, often influenced by regional economic structures, sectoral characteristics, and firm-specific factors. Existing studies predominantly focus on high-income economies, where firms typically have better access to digital infrastructure and resources, but less attention has been paid to how digital transformation influences firms operating in low- and middle-income economies, where resource constraints and market conditions pose unique challenges [

7,

8]. This is particularly evident in the financial sector, where digital transformation through FinTech has shown both promise and limitations for promoting financial inclusion in emerging markets [

9].

Emerging economies, such as Vietnam, offer a compelling context for studying the impacts of digital transformation. Vietnam has experienced rapid digitalization, driven by both private sector initiatives and national policies aimed at enhancing competitiveness in the global market. Key government programs—such as the National Digital Transformation Program and project for developing human resources for national digital transformation—aim to promote the adoption of digital technologies across sectors, with specific support for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) through training, incentives, and infrastructure investment. As of 2023, Vietnam’s digital economy accounted for over 12% of its national GDP, with government targets set at 20% by 2025 and 30% by 2030 [

10]. The government’s promotion of platformization has reshaped firm operations by expanding market access and improving efficiency, while also intensifying competition and putting downward pressure on margins. These changes are crucial for reducing regional productivity gaps and advancing more inclusive industrial development. Despite these shifts, research on digital transformation in Vietnam remains limited, with most studies focused on adoption rather than performance outcomes [

11]. This gap highlights the need for context-sensitive studies that examine both the drivers and impacts of digital transformation in transitional economies.

In addition to contextual gaps, several methodological challenges continue to hinder progress in digital transformation research. A recurring issue is endogeneity: firms with stronger performance are often more likely to adopt digital transformation, which leads to biased estimates. While instrumental variable (IV) methods are commonly employed to address this problem, the difficulty of identifying valid instruments limits their reliability and broader applicability [

12]. Moreover, many existing studies rely on interaction terms or moderation models to explain performance heterogeneity, which often oversimplifies how firms respond to digital transformation across different sectors and conditions. There remains a pressing need for more rigorous empirical approaches that can simultaneously address the self-selection bias and capture the outcome heterogeneity in firm performance [

11]. Additionally, much of the literature focuses primarily on the adoption stage, offering limited insights into the performance implications of digital transformation post-adoption [

13].

To address these limitations, this study examines the drivers and performance effects of platformization—a form of digital transformation involving integrated systems such as supply chain management and product data management—within the context of a developing and transitional economy. Specifically, we ask the following questions: (1) What factors influence firm-level platformization decisions across sectors in Vietnam? and (2) How does platformization affect firm performance, and how do these effects vary across the performance distribution?

This study focuses on Return on Sales (ROS) as the primary measure of firm performance. ROS captures both operational efficiency and pricing power, is consistently available in firm-level data, and enables a comparison across sectors with differing capital intensity. It provides a meaningful lens to assess the profitability implications of digital transformation in a context marked by structural and financial heterogeneity. The objective of this study is to develop a sector-sensitive, firm-level understanding of how platformization both emerges and affects financial outcomes in a resource-constrained environment. By combining an endogenous switching regression model with quantile analysis, we produce robust, context-aware evidence on the strategic and distributional effects of digital transformation. In doing so, the study extends existing methods by applying this combined approach to the context of digital transformation in a transitional economy, where structural heterogeneity and selection bias are central concerns.

Beyond its empirical contributions, this study is conceptually grounded in the RBV and the DCV, which guide our understanding of how digital transformation interacts with firm-level resources and constraints. RBV and DCV offer complementary insights into how firms derive competitive advantage—through the possession of valuable and scarce resources (RBV) and through the ability to adapt and reconfigure these resources in dynamic environments (DCV). We focus, in particular, on platformization as a mechanism that enhances resource utilization and mitigates disadvantages such as high leverage or locational remoteness. Sector-specific findings highlight that digital transformation’s performance effects are not uniform, reinforcing the importance of contextualizing digital strategies within the industrial structure.

This study makes three contributions. First, it provides rare empirical evidence on the digital transformation from a transitional economy where national digital strategies are reshaping industrial development but firm-level outcomes remain underexplored. Second, it links adoption decisions with performance effects using firm-level data across four sectors, offering a nuanced view of how platformization translates into financial outcomes. Third, it applies an endogenous switching regression model—complemented with quantile regression—to jointly estimate selection and outcome heterogeneity. This approach captures both causal effects and distributional differences, offering methodological value for studying digital transformation in resource-constrained settings.

This study contributes to empirical and theoretical knowledge, and the development of analytical frameworks that can inform corporate strategy and governance. Our methodological design supports more accurate decision-making for both policymakers and corporate leaders seeking to promote inclusive and sustainable digital development. In this light, digital transformation should not be viewed solely as a technological upgrade, but as a strategic and fiduciary responsibility. As argued by [

14], integrating innovation and sustainability into governance falls within the evolving interpretation of fiduciary duty, particularly in contexts where digital innovation is central to competitiveness and resilience. Our findings support this perspective, showing that uneven gains from digitalization can be addressed through informed, context-sensitive strategies.

Finally, this study aligns with the broader agenda of sustainable development by analyzing how digital transformation contributes to economic sustainability and resilience in a transitional economy. As digital technologies reshape firm behavior, understanding their impact on profitability and competitiveness is essential for promoting inclusive and long-term economic growth, especially in resource-constrained environments like Vietnam. By examining the heterogeneous effects of digitalization across sectors and firm types, the study informs policies aimed at fostering sustainable industrial development, reducing productivity gaps, and supporting digital inclusion. These insights contribute to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), and are especially relevant for policymakers balancing technological progress with equitable economic transformation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on digital transformation, focusing on its impact on firm performance, key measurement approaches, and methodological challenges.

Section 3 outlines the research methodology, including the data, variables, and the endogenous switching regression model used to estimate the determinants of digital transformation adoption and firm performance.

Section 4 presents the empirical results and discusses the findings in the context of existing theories and the economic environment in Vietnam. Finally,

Section 5 concludes by summarizing the key contributions, offering managerial and policy implications, and suggesting avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

Digital transformation has become a central focus in organizational and strategy research, especially as firms increasingly adopt digital technologies to reshape business models, improve efficiency, and respond to volatile environments. In both developed and developing economies, the integration of platforms, including the supply chain management (SCM), product data management (PDM), and information systems, has introduced new pathways for firms to enhance performance. To understand the strategic drivers and consequences of such transformations, scholars have drawn on foundational theories in strategic management. Among these, the RBV and the DCV have emerged as two dominant frameworks. This section reviews these perspectives to frame our conceptual and empirical approach to platformization and its performance implications.

2.1. Digital Transformations: Theoretical Foundation

The decision to adopt digital transformation, including platformization, is commonly analyzed through the lens of strategic management, particularly the RBV and the DCV. These frameworks, widely used in organizational economics and management theory, provide insights into how firms develop and leverage internal assets to gain and sustain competitive advantage. The RBV, originating with Wernerfelt [

3] and formalized by Barney [

4], emphasizes the strategic role of tangible and intangible resources—such as financial assets, human capital, and technological capabilities—in shaping firm performance. From this perspective, resource-rich firms are better positioned to adopt digital transformation, as they can more easily mobilize the capital and knowledge needed to implement complex digital systems. However, the RBV often assumes relatively stable environments and resource abundance, which limits its applicability to developing economies.

To address the limitations of the RBV in dynamic environments, the DCV—developed by Teece, Pisano, and Shuen [

5]—emphasizes a firm’s ability to sense opportunities, seize them, and reconfigure resources to maintain competitiveness [

15]. This framework extends the RBV by accounting for the need for continuous adaptation in volatile and resource-constrained settings, making it particularly relevant for transitional economies. As noted by [

16], dynamic capabilities include both organizational agility and strategic foresight, which are crucial for firms navigating institutional instability and market turbulence. However, existing applications of the DCV often underemphasize the role of subjective managerial perceptions and contextual uncertainties in shaping digital adoption. By incorporating firm-level perceptions into the analysis, this study builds on and extends the DCV logic to better capture the strategic decision-making processes in digitally transforming firms.

Firms undergoing digital transformation face a dual imperative: to leverage digital tools to enhance performance and competitiveness, and to adapt organizational structures, resources, and capabilities to rapidly evolving technological and market environments. The RBV offers a foundational lens to understand how firm-specific assets, including digital infrastructure and human capital, can generate a sustained competitive advantage when they are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable [

3,

4]. However, RBV’s relative emphasis on static resource possession has been critiqued for not adequately capturing the dynamic nature of digital competition [

5]. In response, the DCV has emerged to emphasize the importance of integrating, reconfiguring, and renewing internal and external competences in rapidly changing environments [

6]. Digital transformation, in this view, reflects a firm’s capacity to adapt through learning, experimentation, and the reorganization of routines [

7]. Prior studies have shown that dynamic capabilities such as sensing, seizing, and transforming can mediate the effect of digital tools on firm outcomes, particularly in uncertain or competitive markets [

8,

9].

Firms adopt digital transformation not only to automate processes but also to reorganize production, integrate supply chains, enhance market reach, and create new value through data-driven services. As the RBV suggests, firms that possess superior digital capabilities can leverage them for competitive advantage, especially when such capabilities are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable [

17,

18]. The DCV further refines this logic, arguing that firms need the ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments [

19,

20]. Thus, digital transformation is not only an outcome of digital investment, but also of organizational adaptation and strategic resource alignment [

21].

In this study, the RBV framework informs our interpretation of platformization as a strategic resource whose value depends on the firm’s internal assets and routines. The DCV perspective guides our empirical approach by emphasizing that digital transformation outcomes depend on a firm’s ability to reconfigure resources—an ability that varies across firms and influences both the decision to adopt platformization and the performance gains that follow. These theoretical lenses directly motivate our use of endogenous switching regression and quantile methods to capture the heterogeneity in both adoption and outcomes.

2.2. Digital Transformations and Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence

A growing body of empirical research has examined the link between digital transformation and firm performance across diverse settings, technologies, and sectors. These studies consistently highlight that, while digital transformation is generally associated with improved performance, the effects are far from uniform and depend on both firm-level capabilities and contextual enablers.

Recent meta-analytic evidence confirms a significant positive relationship between digital transformation and performance, with stronger effects observed in manufacturing sectors and developing economies [

22]. This reinforces the relevance of digital transformation as a driver of economic upgrading in contexts like Vietnam. At the firm level, [

23] uses a text-mining-based digital transformation index to show that digital initiatives in Chinese manufacturing firms improve profitability, particularly via cost reductions and innovation. Similar findings are found in [

24]: digital transformation enhances cost efficiency and innovation, which translate into gains in return on assets (ROA) and equity (ROE), especially for firms at mature stages.

Other studies have explored the mechanisms and heterogeneity more explicitly. One line of research, using quantile regression, finds that digital transformation improves innovation output and efficiency, with stronger gains among firms closer to the technological frontier [

25]. Another study identifies organizational capital as a key moderator, showing that digital transformation enhances firm value only when supported by strong internal coordination and governance structures [

26]. A similar conclusion emerges in the ESG context, where digital transformation alone has a limited impact on firm valuation, but its interaction with ESG practices leads to substantial performance gains [

27].

Studies using structural modeling approaches highlight the importance of sequencing and the depth of digital adoption. Evidence from an instance of sequential modelling with small firms in South Africa shows that simple digital tools such as mobile technologies and social media enhance innovation and productivity by improving information access [

28]. Similarly, research based on a Difference-in-Differences with Propensity Score Matching (DiD-PSM) framework in Italy finds that productivity gains rise with both the number and sophistication of digital technologies adopted, with artificial intelligence (AI) tools yielding the strongest effects [

29].

A consistent insight across these studies is the presence of threshold effects: performance improvements from digital transformation often materialize only when firms possess complementary capabilities or reach a certain scale. This pattern is further supported by [

30], who report a J-shaped relationship between digitalization and firm performance in U.S. firms, with internationalization and FDI inflows amplifying the gains. These findings suggest that the benefits of digital transformation depend on firms’ internal resources, absorptive capacity, and alignment with contextual conditions—factors that directly inform this study’s empirical strategy.

2.3. Digital Transformation in Developing and Transitional Economies

Digital transformation is increasingly recognized as a catalyst for economic restructuring in developing economies. By enabling platformization and enhancing access to broader markets, digital transformation fosters structural changes across industries, contributing to improved productivity and competitiveness. In countries like Vietnam, where digitalization is a national priority, platform-based transformation has reshaped traditional business models as part of a broader strategy to modernize the industry and strengthen global integration.

Digital innovation offers the potential for firms in developing economies to leapfrog the traditional stages of industrialization by improving operational efficiency, expanding market access, and upgrading product and service quality [

7,

11]. However, these benefits are often constrained by systemic barriers such as inadequate infrastructure, limited access to capital, and pronounced regional disparities in digital readiness [

7,

8]. For instance, rural SMEs frequently lack the digital infrastructure available in urban centers, hindering their competitiveness. Successful transformation in such contexts requires coordinated efforts across policy, infrastructure, and firm-level capabilities.

Importantly, digital transformation is not just a matter of technological adoption but involves deeper shifts in organizational routines, workforce capabilities, and strategic orientation. Effective digital innovation, particularly in SMEs, depends on integrating individual, organizational, and environmental factors [

11]. Firms must develop dynamic capabilities to sense digital opportunities, seize them, and reconfigure resources to sustain advantage in volatile markets. When supported by inclusive digital policy and infrastructure investment, this transformation enhances both firm resilience and equitable industrial upgrading.

The institutional and environmental conditions in transitional economies significantly shape digital transformation outcomes. Unlike high-income countries where digitalization is largely market-driven, digital adoption in Vietnam is shaped by structural constraints and guided by government-led initiatives. National programs—such as the country’s digital transformation strategy and its long-term vision for innovation and industrial upgrading—reflect a strong policy commitment to integrating digital technologies into the broader development agenda. These initiatives emphasize state support for digital infrastructure, capacity building, and technology diffusion across sectors [

13,

14,

15].

Policymakers play a vital role in addressing persistent digital divides. Financial incentives, digital infrastructure investment, technology adoption programs, and sectoral knowledge-sharing networks are increasingly used to accelerate adoption across firm sizes and sectors [

24]. Policies targeting infrastructure gaps and digital literacy—especially in rural and underserved areas—are essential for ensuring that smaller firms can benefit alongside larger enterprises. In this regard, digital transformation should be seen not only as a tool for efficiency but also as a mechanism for long-term economic sustainability and inclusion.

Vietnam’s experience reflects broader regional trends. Evidence from China shows that the Big Data Pilot Zone (BDP) policy significantly improved firm-level productivity, especially among non-state firms with a strong managerial capability [

31]. Another study finds a U-shaped relationship between digital economy development and productivity, with mid-sized and centrally located firms benefiting the most—highlighting the importance of contextual factors such as geography and firm characteristics [

32].

Similar findings highlight the enabling conditions for digital transformation. One study shows that digital finance can alleviate credit constraints, thereby facilitating adoption—particularly among smaller, private firms [

33]. Additional evidence emphasizes the role of outward internationalization and foreign direct investment in enhancing digital transformation outcomes in U.S. firms, offering relevant insights for transitional economies participating in global value chains [

30].

At the firm level, outcomes vary according to internal capacity and sectoral conditions. Evidence from China shows that platform-based technologies—such as supply chain and PDM systems—enhance manufacturing performance by boosting process innovation and reducing costs [

23]. In South Africa, even informal micro-enterprises have been shown to benefit from digital communication technologies, which stimulate innovation and productivity in resource-constrained settings [

28]. Together, these findings highlight the importance of firm capabilities, institutional quality, and sectoral linkages in shaping the outcomes of digital transformation [

16,

34,

35].

In Vietnam, digital transformation remains uneven across sectors and regions. Digital intensity is generally higher among exporters and state-owned enterprises [

24,

36], while private domestic SMEs often face greater challenges due to cost concerns, skill shortages, and uncertainty about digital returns. This aligns with the recent empirical research and case studies [

37,

38]. Additionally, concerns over labor displacement and digital inequality persist, particularly in sectors with large informal workforces.

In sum, digital transformation holds substantial promise for accelerating economic restructuring in transitional economies. Yet, its success depends on the interplay among national policy, infrastructure development, firm-level capabilities, and institutional context. This study contributes to the literature by examining how platformization—a core aspect of digital transformation—shapes firm performance within the context of Vietnam’s ongoing economic transition.

2.4. Methodological Advances in Estimating Digital Transformation Effects

Estimating the effects of digital transformation on firm performance presents two persistent methodological challenges: endogeneity in adoption decisions and heterogeneity in outcomes. Firms that adopt digital transformation are often systematically different from non-adopters—typically possessing greater resources, stronger management, or prior growth trajectories—leading to selection bias and complicating causal inference.

To address endogeneity, researchers have employed IV regression using regional or industry-level digital transformation averages as instruments [

34,

35]. However, the exogeneity of these instruments is frequently questioned, as they may also directly affect firm performance [

24]. Other common strategies, such as lagged variables or proxy-based controls, often introduce additional bias or fail to capture the complexity of digital transformation adoption dynamics.

Quasi-experimental designs have gained traction as alternatives. DiD PSM, as used in studies like [

29,

31], help control for observable differences between treated and control firms. Yet, these approaches remain limited when the selection arises from unobservable firm characteristics. Structural models such as the sequential modelling approach [

28] and system GMM have also been employed to capture feedback loops and innovation dynamics, though these models often require strong identifying assumptions.

Alongside endogeneity, researchers increasingly recognize that digital transformation effects are not uniform across firms. Recent studies emphasize that the performance effects of digital transformation depend on mediating mechanisms such as business model innovation [

39], the firm’s distance to the technological frontier [

40], and organizational alignment during digital mergers and acquisitions [

41]. Contextual disruptions, such as pandemics or natural disasters, have also been shown to shape digitalization outcomes, particularly for non-technological firms [

42].

Quantile regression, as applied in [

25,

43], reveals that high-performing firms tend to derive greater benefits from digital adoption—findings consistent with theories of absorptive capacity and resource-based heterogeneity. However, these approaches typically do not correct for endogeneity, limiting their causal interpretability.

Mediation and moderation analyses further illuminate how and under what conditions digital transformation affects firm outcomes. Mediation models identify mechanisms such as improved asset turnover, lower operating costs, and innovation success [

24,

34], while moderation analyses reveal that factors like environmental performance, organizational capital, or regional competition may amplify or attenuate digital transformation effects [

34,

35,

36]. Yet, these analyses are often conducted separately from causal identification strategies, resulting in partial insights.

Moreover, few empirical approaches consider the role of managerial perceptions in shaping digital transformation decisions. In resource-constrained settings, strategic foresight—not just current capacity—can drive adoption. By incorporating managerial expectations about future competition and profitability [

11,

19], researchers can better explain the variation in adoption under uncertainty.

This study addresses these gaps by employing an Endogenous Switching Regression (ESR) model that simultaneously estimates the determinants of digital transformation adoption and its heterogeneous effects on performance. This method corrects for self-selection based on unobservables and allows for different outcome equations for adopters and non-adopters. Combined with quantile regression, our approach explores distributional effects, offering insights into which firms benefit most from digital transformation. This integration of causal inference with heterogeneity estimation enhances robustness and interpretive power.

To address these empirical challenges, this study adopts an ESR model combined with a quantile-based analysis to provide a more robust assessment of digital transformation effects. While ESR is a known method to account for selection bias, its application in digital transformation studies—particularly in transitional economies—remains limited. By simultaneously modeling adoption and outcomes for adopters and non-adopters, and allowing heterogeneous effects across the performance distribution, our approach captures both the selection and outcome heterogeneity. This integrated strategy offers practical value for empirical research on digital transformation, where both unobserved self-selection and uneven benefits are central concerns. Thus, our contribution lies in refining the identification of digital transformation effects by aligning the model choice with the theoretical complexity of the phenomenon.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

This study uses data from the 2020 Vietnam Enterprise Survey (VES), conducted annually by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam (GSO). The VES is a nationwide census that collects comprehensive information on the operations, inputs, outputs, and financial indicators of all registered firms. The 2020 wave includes a special module on digital transformation, capturing responses from approximately 8000 randomly selected firms. While labeled as 2020, the data primarily reflect firm activities during fiscal year 2019 and early 2020—before Vietnam experienced widespread pandemic-related disruptions. The 2020 wave offers a rare opportunity to analyze firm-level digital transformation using nationally representative data, as it is the first to include detailed metrics on digital platform adoption across sectors.

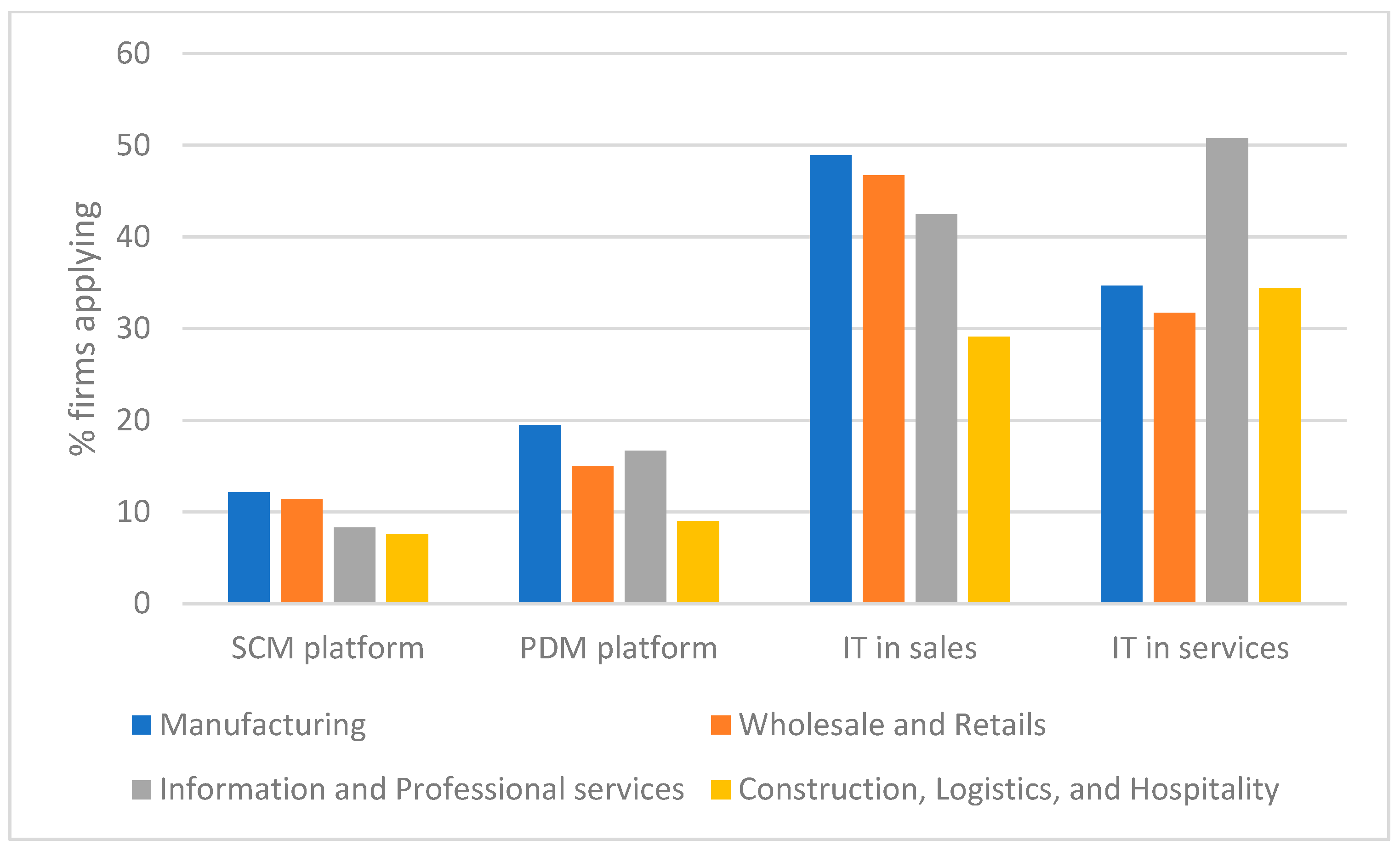

To ensure analytical focus and comparability, we classify firms into four major sectors: (1) manufacturing; (2) wholesale and retail; (3) information and professional services; and (4) construction, logistics, and hospitality. These sectors are selected based on their strategic importance to Vietnam’s digitalization strategy, their varying levels of digital maturity, and their distinct production and service characteristics. Manufacturing (2370 firms) represents industrial automation and supply chain integration; wholesale and retail (946 firms) capture consumer-facing digital adoption; information and professional services (761 firms) are inherently digital-intensive; while construction/logistics/hospitality (1447 firms) represent traditional sectors undergoing digital catch-up. After excluding firms with missing data or inconsistent responses, the final sample includes 5542 firms, covering all regions and firm size categories, ensuring the robustness and representativeness of the analysis.

3.2. Model Specification and Variable Definitions

The model specification and variable selection in this study are informed by the RBV and the DCV. According to the RBV, platformization enhances the productivity of valuable firm-specific resources (e.g., assets and cash flow) by embedding them in digitally enabled processes. Meanwhile, the DCV emphasizes firms’ abilities to reconfigure and adapt these resources in response to dynamic environments, particularly in resource-constrained and transitional contexts. These perspectives guide our choice of performance measure, model structure, and the inclusion of firm-specific and contextual variables that capture both resource endowments and adaptive capacity.

Platformization in this study refers to the adoption of three specific digital technologies: Supply Chain Management (SCM) systems, Product Data Management (PDM) systems, and IT solutions for logistics and sales. Firms are classified as platformizing if they report using any one of these technologies. While this binary classification does not capture the intensity or scope of digital adoption, it is supported by prior literature that links these technologies directly to operational and financial performance. Integration of SCM and ERP systems has been shown to improve decision-making and enhance firm performance [

19], while ERP systems positively influence performance through supply chain integration [

20]. SCM also plays a mediating role in improving financial outcomes [

21], and PDM systems contribute to better technical data management, product quality, and process efficiency [

37,

38,

44]. These studies collectively support the use of SCM, PDM, and IT systems as valid proxies for digital platformization.

ROS is used as the proxy for firm performance, as it directly reflects operational efficiency and profitability relative to revenue—key dimensions influenced by digital platformization. ROS is particularly suitable in the context of heterogeneous firm sizes and sectoral structures, where profit margins offer a more normalized measure of firm outcomes than absolute profit or revenue. Platformization decisions and performance outcomes are jointly estimated using an endogenous switching regression framework [

45], which corrects for potential selection bias by modeling the decision to platformize through a selection equation and estimating separate performance equations for platformized and non-platformized firms. The selection equation is given by

where

is a latent variable of which the realization

if

and

otherwise, and

is the set of covariates explaining the decision to platformize,

the corresponding parameters, and

the error term. The set of covariates

includes firm size, financial indicators, owner’s perception regarding digital transformation, and firm characteristics.

Firm size is a significant factor influencing platformization, as larger firms typically possess more resources to invest in digital technologies and face operational complexities that can benefit from platformization (RBV) [

11]. In this study, firm size is measured using two proxies: total assets and the number of employees. These proxies capture firms’ financial and human resource capacity, which are critical for implementing digital platforms. Larger firms are generally better positioned to adopt complex digital systems due to their ability to allocate substantial resources toward innovation [

4]. Labor, defined as the average number of employees, is included in the platformization decision equation but excluded from the performance equations. This approach is consistent with prior research, which suggests that, while labor is an important factor in strategic decisions, its influence on short-term financial outcomes is less direct [

8].

Financial indicators used in this study include leverage, capital intensity, and net cash flow. These variables are essential for understanding a firm’s financial capacity and constraints in adopting digital platforms. Leverage, measured as the ratio of liabilities to total assets, reflects a firm’s financial obligations. High leverage can deter platformization due to the increased financial risk and reduced flexibility it imposes on firms (DCV) [

34]. Capital intensity, defined as the ratio of assets to sales, indicates the extent to which a firm relies on fixed assets in its operations. Firms with high capital intensity may adopt platforms to better manage their asset base and enhance operational efficiency (RBV) [

17]. Net cash flow, calculated as the ratio of cash to total assets, represents a firm’s liquidity. Strong cash flow enables firms to absorb the upfront costs of digital transformation and sustain ongoing investments required for successful digital adoption [

11].

Managerial perceptions of digital transformation’s potential impact on profitability and competitiveness are critical determinants of platformization decisions (DCV). These perceptions are captured through two binary variables. The first variable indicates whether managers believe that digital transformation will increase profitability in the next three years, while the second reflects whether managers expect digital transformation to enhance competitiveness over the same period. These variables serve as proxies for strategic foresight, capturing the extent to which managers anticipate long-term benefits from digital transformation. Previous studies have highlighted the role of managerial expectations in shaping strategic decisions, particularly in uncertain environments where future returns on digital investments are difficult to predict [

11,

44].

The ownership structure is another key variable influencing platformization (DCV). This study categorizes ownership into three types: state-owned enterprises (SOEs), foreign-owned enterprises, and private domestic firms. SOEs often face bureaucratic inertia, which can slow down the adoption of new technologies despite their access to government resources [

46]. In contrast, foreign-owned and private domestic firms tend to be more agile and innovation-driven, making them more likely to adopt digital platforms [

8]. The ownership variable allows for an examination of how different ownership types influence the likelihood of adopting digital transformation, reflecting the heterogeneity in strategic behavior across firms.

Location is also a critical determinant of platformization (DCV). In this study, a dummy variable is used to identify firms located in Vietnam’s large cities, including Hanoi, Hai Phong, Da Nang, Ho Chi Minh City, and Can Tho. Firms in these cities benefit from better infrastructure, a more skilled workforce, and greater exposure to competitive pressures, all of which encourage digital adoption [

11,

47]. By including a location variable, the study accounts for regional disparities in infrastructure and market conditions, providing insights into how urban advantages influence platform adoption rates.

The institutional context is captured through the Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI), a comprehensive measure of governance quality at the provincial level. Developed by the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) in collaboration with USAID, the PCI is based on annual surveys of approximately 10,000 businesses and incorporates additional data from government agencies. It evaluates ten key dimensions, including market entry, access to land, transparency, time costs of regulatory compliance, informal costs, and the proactivity of provincial leadership. Higher PCI scores indicate better governance and a more supportive business environment. By including the PCI in the analysis, this study assesses whether governance quality facilitates platformization by reducing institutional barriers and fostering innovation. This variable is particularly relevant in Vietnam, where significant regional differences in governance quality exist. Understanding how these differences affect digital adoption can provide valuable insights for policymakers aiming to create a more business-friendly environment across regions.

The use of the endogenous switching regression model aligns with the DCV by allowing us to estimate heterogeneous performance outcomes across firms with different adaptive capabilities—those who adopt platforms and those who do not—while correcting for selection bias in the platformization decision. The firm performance of the two groups of firms are given by the following:

In this setting, and are the ROS of non-platformizing and platformizing firms, is the set of covariates explaining firm performance, and and are corresponding coefficients of the two groups. The covariates for the firm performance (ROS) equations of both platformizing and non-platformizing firms are similar to those used in the platformization equation, with some adjustments. First, the assets and capital intensity entered as levels in the selection equation because the probit model is already non-linear, but as logarithm in the firm performance equation. Second, labor and the owner’s perception of digital transformation are excluded, as they are not expected to impact current firm performance directly. Additionally, assets and capital intensity are expressed in logarithmic form to capture diminishing returns as firm size or capital intensity increases. Finally, leverage is included in a quadratic form to account for a potential non-linear relationship, where moderate levels of leverage may enhance performance, but excessive leverage could have negative effects.

3.3. Estimation Method

The error terms

and

, together with

, are assumed to have a trivariate normal distribution with zero mean and a covariance matrix

where

is the variance of the error term of the platformization equation, which is assumed to be equal to 1,

and

are the variances of the error terms in the firm performance equations,

is the covariance between

and

, and

is covariance of

and

The covariance of

and

is unidentified, because we cannot observe the firm performance for the same firm in both states of platformizing and non-platformizing.

The coefficients of Equations (1)–(3) are estimated simultaneously in the endogenous switching model using the data for

,

and

by maximizing the log-likelihood function

where

is a cumulative trivariate normal distribution function,

normal density function, and

where

is the correlation coefficient between

and

. The model can be implemented using the

movestay command in Stata 15, which is specifically designed for estimating endogenous switching regression models.

3.4. Robustness Check

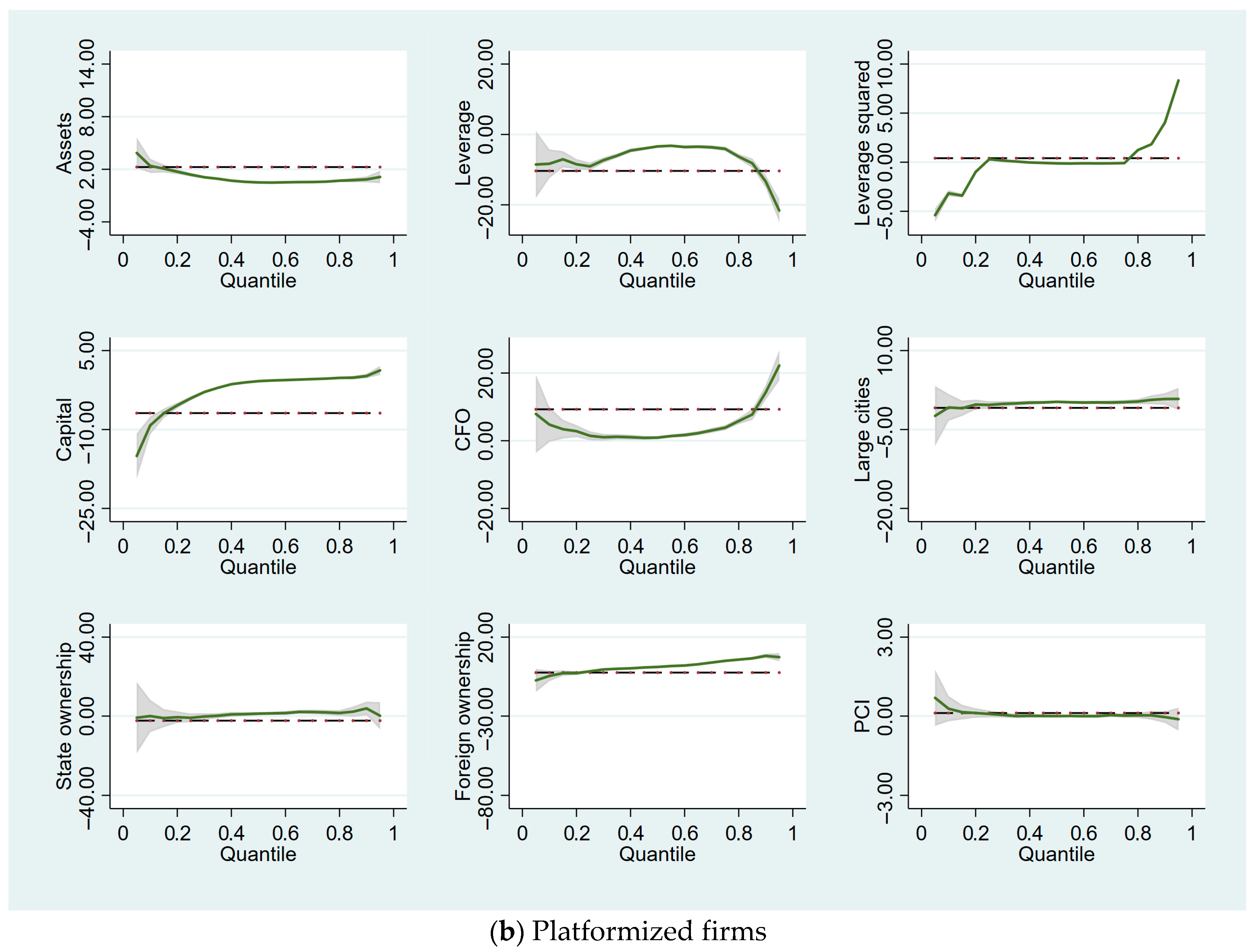

To examine the robustness and distributional heterogeneity of digital transformation impacts on firm performance, we complement the endogenous switching model with quantile regression analysis. Quantile regression, introduced by [

48], estimates covariate effects at different points of the conditional distribution of the dependent variable, rather than focusing solely on the mean. This method is particularly suitable for identifying whether the determinants of firm performance vary across low-performing, median, and high-performing firms. The same set of covariates used in the ROS equations of the switching model is employed here, and estimations are conducted separately for platformized and non-platformized firms within each sector. Quantile regressions are estimated across a wide range of percentiles—from the 10th to the 90th—to capture the full distributional heterogeneity in firm performance, using bootstrapped standard errors to ensure robust inference. This approach allows us to validate the stability of our core findings and uncover performance heterogeneity that mean-based models may overlook.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a new understanding of the drivers and impacts of platformization on firm performance and makes both theoretical and methodological contributions, while offering evidence from the context of a developing economy. Theoretically, it advances the RBV and DCV by illustrating how platformization interacts with tangible and intangible resources to optimize firm performance. The research highlights that platformization amplifies the positive effects of assets and liquidity on sales performance, particularly in capital-intensive sectors, while mitigating the adverse impacts of a high leverage and locational disadvantages. Sector-specific findings from manufacturing, wholesale and retail, information and professional services, and construction/logistics/hospitality extend the literature by revealing that the effects of digital adoption on resource utilization and profitability are highly heterogeneous. These results emphasize the importance of aligning digital transformation strategies with sectoral and operational realities to support sustainable and inclusive industrial upgrading.

Methodologically, the study demonstrates the advantages of the ESR over a traditional moderation analysis and IV regressions. By simultaneously estimating firm performance equations for platformized and non-platformized firms, this approach captures the structural heterogeneity and selection bias, offering a more nuanced understanding of platformization’s effects. Additionally, the inclusion of quantile regressions reveals distributional differences in performance impacts across the sales performance spectrum, showing that platformization has more pronounced benefits for firms at the median and upper quantiles. These findings address the gaps in prior research that focused only on mean effects and uniform interaction terms, offering a more robust framework for evaluating digital transformation. By focusing on Vietnam—a rapidly developing economy undergoing significant digital and structural transformation—the study contributes context-sensitive insights into how platformization supports the broader processes of market reform and economic upgrading. This contextual relevance enhances its applicability to other transitional economies, offering a more robust framework for evaluating digital transformation within the context of equitable economic resilience and structural reform.

From a sustainability perspective, the study contributes to the understanding of how digital transformation can support economic and social sustainability in emerging markets. Platformization enhances resource efficiency, reduces the spatial inequalities in performance, and promotes the broader access to digital infrastructure and tools. These outcomes are especially relevant to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), where platformization plays a strategic role in improving productivity, expanding access to digital infrastructure, and reducing firm-level disparities. By identifying heterogeneous effects across sectors and firm types, the study supports the design of more inclusive and equitable digitalization strategies.

From a policy standpoint, the findings provide actionable guidance. First, firms with a high capital intensity or leverage should integrate platformization with effective cost and financial management to fully realize performance gains. Second, the influence of managerial perceptions on platformization underscores the need for programs that develop strategic foresight among business leaders. Training and awareness initiatives can help managers better understand the long-term value of digital transformation, especially in under-digitized sectors. Third, while platformization reduces firms’ dependence on urban advantages, continued investments in digital infrastructure and talent development in non-urban areas remain critical for equitable transformation. By identifying the conditions under which digital adoption leads to more equitable and efficient outcomes, this study contributes to the broader sustainability agenda and provides evidence for designing inclusive digital development strategies in transitional economies.

Despite its contributions, the study has limitations that suggest directions for future research. The analysis is based on data from a single national context, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Comparative studies across countries with varying institutional and technological landscapes could offer deeper insights into the contextual determinants of platformization. Furthermore, the binary treatment of platformization does not capture the full range of digital adoption. Future work should consider more granular, continuous measures to assess the intensity and sophistication of platform use. Lastly, while this study emphasizes managerial perceptions, further research could explore how leadership traits, organizational readiness, and environmental pressures interact to shape digital transformation trajectories.