Abstract

A key aspect of ensuring efficient management of gastronomic tourism is understanding the demand behavior. The studies conducted so far are limited to analyzing this demand in specific destinations, making it impossible to extrapolate their results to obtain a global profile of the gastronomic tourist. This study aims to address this gap by providing a more generalizable characterization and identifying a series of segments of gastronomic tourists. This has been achieved through a survey conducted with 421 gastronomic tourists on an international scale, using descriptive statistics and latent class analysis (LCA). The results obtained have provided insight into the behavior, willingness to pay, expectations, and experiences of those surveyed. From this, three segments of gastronomic tourists with clearly different profiles have been identified. These findings offer a precise understanding of the demand for gastronomic tourism and provide a strategic basis for designing tailored, conscious policies aimed at maximizing the cultural and economic value of the food heritage of different tourist destinations.

1. Introduction

Gastronomic tourism has emerged with significant force in the global tourism industry [1]. Its influence on travelers’ decisions and its substantial contribution to the economic development of various regions have been demonstrated in numerous scientific studies [2,3,4,5].

Despite its novelty, gastronomic tourism enjoys significant representation in current tourism practices, thanks to its dynamism and the ease with which it complements different types of tourism in any territory [6,7].

In this context, this research begins by acknowledging this importance and, at the same time, recognizing a latent deficiency in the scientific study of the general profile of the gastronomic tourist [8] (since the studies conducted so far are limited to analyzing this profile in specific destinations, which means their results, unfortunately, cannot be used to obtain a global profile of the gastronomic tourist).

Understanding the behavior, willingness to pay, expectations, and experiences of gastronomic tourism demand is a fundamental input for supporting scientifically based tourism planning and management in various destinations [9,10]. This fact justifies the need for a study such as the one presented in this article.

The need to complement the existing scientific corpus on the gastronomic tourist with an updated profile is justified by the dynamic evolution of travelers’ preferences and behaviors in this specific area. Given the constant growth of this type of tourism within the global tourism industry, it is imperative to accurately understand the demographic and psychographic characteristics of contemporary gastronomic tourists, as well as their motivations and expectations regarding the experiences offered.

Several authors [6,11,12] and even the [1] have emphasized the need for constant and in-depth research into tourism types and their profiles. However, in the case of gastronomic tourism, the lack of comparable scientific research that comprehensively addresses this topic magnifies this need.

This research responds to the lack of universally applicable knowledge about the demand for gastronomic tourism, which limits the formulation of concrete actions for tourism development through gastronomic tourism and represents a significant gap in scientific knowledge. Therefore, this study becomes a valuable tool for decision-making and serves as a reflection instrument for those seeking rigorous and reliable information related to gastronomic tourism.

In this context, the objective proposed in this research is twofold. On one hand, to conduct a characterization of the demand for gastronomic tourism that is more universal than those known so far. On the other hand, to identify a series of segments of gastronomic tourists and get to know their main characteristics, to facilitate decision-making processes for stakeholders in touristic destinations committed to gastronomic tourism.

The main contribution of this research is twofold. On one hand, the characterization of the demand for gastronomic tourism is generalizable and, on the other hand, the selection of the three segments of gastronomic tourists obtained is clearly relevant in terms of contributing to the understanding of this type of demand, facilitating decision-making processes for stakeholders involved in tourist destinations that are committed to gastronomic tourism.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Characterization of the Demand for Gastronomic Tourism

Scientific research on the demand for gastronomic tourism has experienced significant growth in recent years, with constant recognition of the potential of demand identification to drive the economic development of destinations through job creation in the tourism, food, and craft industries [5] as well as the promotion of regional products [13,14] However, there is no actual characterization, and most related studies highlight aspects that allow proximity to their practices but are limited to providing an approximate view of an activity scientifically recognized as complex and multidimensional.

In relation to the motivations for gastronomic tourists’ journeys, studies show that they are diverse and depend on the particularities of the destinations. However, they emphasize the interest in authenticity [15], culture, the value of local products [11], and the exploration of new flavors [16]. Several studies also highlight the cultural impact that demand has on the preservation and promotion of gastronomic heritage [17,18], reflected in the appreciation of traditional cuisine and the creation of specialized experiences [19].

Regarding consumption behaviors, several studies analyze travelers’ food preferences, with a focus on local and sustainable foods [10,20]. The value of the experience also plays an important role in the scientific literature, with research on the influence of factors such as preformed image and destination reputation [4,21], the ambiance of spaces, the presentation of dishes, and interaction with local chefs and producers [14,19,22].

In the most recent scientific production, there is growing interest in integrating sustainable practices into gastronomic tourism, such as the application of emerging technologies to enhance the traveler’s experience [23,24,25]. Moreover, gastronomic motivation significantly influences destination selection, while satisfaction and loyalty levels are affected by gastronomic experiences [7]. Both topics require a concrete understanding of demand for proper analysis.

Trend analysis refers to the search for authenticity [26,27] flavor exploration, and food preferences [8], as well as a desire for connection widestination’s identity [28], and a growing awareness of sustainability [29]. However, while these analyses provide an apparent diversity of information for researching gastronomic tourism demand, they present superficial trends for characterization [30] as none of the studies delve into tourists’ specific expectations, willingness to pay, or specific behaviors. Furthermore, being focused on specific destinations, they limit the understanding and identification of demand in a deep manner, or as a foundation for the effective development of management policies and strategies.

2.2. Gastronomic Tourism Demand Profiles

When delving deeper into the analysis of gastronomic tourism demand, segmenting its profiles is an important tool for optimizing the planning, promotion, and management of destinations. Generally speaking, most available research focuses on the food service sector and considers gastronomic tourism as a novelty. These studies recognize it as an increasingly popular and high-value type of tourism due to the relationship between gastronomy, destination economies, and territorial development.

There are studies that identify certain groups of consumers and their preferences in terms of gastrotouristic experiences [3,9] and that specialize in specific products by region, such as oil, beer, cocoa and chocolate, coffee, ham, cheese, tequila, and wine, among others.

Recent studies synthesize the concept of gastronomic tourism through literature reviews or by using methodologies that reveal an evolving demand undergoing a segmentation phase that influences general tourism practices [31] and primarily local economies [10].

In the specific analysis, there are studies that segment particularly gastronomic demand (generally, not tourists) in restaurants serving typical cuisine in various countries. They are based on motivation and satisfaction with the service, and their results are intended to help understand market segments and improve demand satisfaction. There are also segmentations that show the behavior of tourists who visit high-end restaurants and analyze their impact on the destinations where they are located [32]. Their results reveal differentiated segments, motivations, and behaviors, highlighting the importance of restaurants as a tourist resource and their potential to contribute to territorial development. The methodology that is used by these studies, generally, is surveys with limited samples of tourists or diners. Two key limitations are noted in these studies: they analyze responses from visitors to specific restaurants and destinations, and they do not discriminate between gastronomic tourists for survey completion; therefore, their scope is limited in relation to the diversity of the existing tourism-gastronomy activities.

It is worth noting that the lack of scientific literature on these topics can be attributed to the logistical complexity and cost of collecting data from various destinations; additionally, the variability in consumption behavior across different contexts increases the difficulty of analysis. With the influence of global trends, technological advances, and destination identity factors, characterizing demand at an international level and identifying specific profiles of gastronomic tourism demand form an important foundation for exploring its interdisciplinarity and addressing emerging market challenges. Therefore, it becomes a highly valuable analytical practice, and hence the interest in this study.

After this exhaustive review of the scientific literature on the subject under study, we are now in a position to propose the hypotheses that will guide this research:

Hypothesis 1.

The demand for gastronomic tourism is influenced by correlated socioeconomic and cultural variables that can be generalized.

Hypothesis 2.

It is possible to identify different profiles of gastronomic tourists, allowing for an understanding of the basic characteristics of each one, thereby facilitating the planning and management of gastronomic tourism destinations.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative techniques to gain an in-depth understanding of gastronomic tourist behavior. The methodological framework was grounded in careful planning and a deliberate selection of variables relevant to the research scope, enabling a holistic analysis and ensuring a structured and methodologically sound treatment of the data.

3.1. Questionnaire and Survey

This research is embedded within a larger research initiative, whose preliminary results are available in the work of [33]. For this, a structured survey instrument was developed through Google Forms, incorporating closed-ended questions to gather data on preferences and budget allocations related to experiential offerings, alongside several open-ended items designed to delve deeper into participants’ motivations and expectations. The final questionnaire included a total of 32 questions: 25 focused on capturing insights into respondents’ behavior, willingness to pay, expectations, and past experiences, while the remaining items were intended to collect sociodemographic information.

The sample of 421 respondents was obtained through purposive and convenience sampling, targeting individuals who stated that the pursuit of culinary experiences was the main reason for their trip. This strategy was adopted due to the absence of a universal sampling frame for “gastronomic tourists” upon which to apply conventional probabilistic techniques. Consequently, it was unfeasible to define and encompass a comprehensive target population at a global scale. Based on this sample size, and assuming maximum variability (p = q = 0.50), the estimated sampling error at a 95% confidence level is ±4.8%.

At first glance, the sample size might appear limited and potentially unrepresentative of the broader population of interest, namely, the gastronomic tourism demand. However, two key considerations support the validity of the sample. Firstly, as will be explained in detail below, the survey was administered exclusively to individuals identified as gastronomic tourists, meaning those whose main motivation for travel is the pursuit of culinary experiences. Thus, while the sample may not be large, it is highly relevant and contextually appropriate. Secondly, the geographical spread of responses enhances the sample’s representativeness, as it includes participants from diverse global regions. The questionnaire’s distribution was guided by the regional classification established by the UN Tourism, leading to the global dispersion of responses illustrated in Table 1. Therefore, although statistical representativeness cannot be definitively asserted, there is a sound basis to consider the sample reasonably representative of the target group.

Table 1.

Description of the variables related to the characteristics of the demand for gastronomic tourism.

Before being circulated, the questionnaire was subjected to a validation process by six experts specializing in areas aligned with the focus of the research. Their input contributed to optimizing the instrument through content refinement, enhancement, and verification. Following this phase, the survey was disseminated via email and strategically promoted by various international organizations dedicated to gastronomic tourism—including the World Food Travel Association, ITER VITIS Europe, the International Wine Tourism Association, and the UNESCO Creative Cities of Gastronomy Network, among others. This dissemination strategy was designed to ensure broad visibility and engagement with gastronomic tourists on a global scale.

It is important to emphasize that the questionnaire was not randomly distributed among international tourists in general, with subsequent filtering to identify those fitting a gastronomic tourist profile. Rather, the sampling strategy was purposefully designed to target individuals with this specific profile from the outset. In any case, this decision does not introduce any self-selection bias, as the respondents were not self-selected. The objective was simply to ensure that the tourists surveyed were gastronomic tourists, allowing for the best use of the financial and time resources available for this research. Ultimately, there is no self-selection because the survey was completed by any gastronomic tourist who received it.

For this reason, the questionnaire was disseminated through organizations closely associated with gastronomic tourism, thereby increasing the likelihood of reaching a relevant and representative sample. This targeting approach was validated by responses to the initial survey question, in which 96.9% of participants indicated a clear interest in exploring the gastronomy of destinations during their holiday travels.

In order to enhance both participation rates and sample diversity, deliberate efforts were undertaken during the dissemination phase, without offering any form of incentive for survey completion. The inclusion of all collected responses in the analysis is supported by the methodological rigor applied and the consistency and relevance of the data obtained. This approach enabled the incorporation of a wide range of perspectives, thereby reinforcing the validity and reliability of the findings, reducing potential selection bias, and optimizing the effectiveness of the resources allocated to data collection.

3.2. Methodological Tools: Descriptive Statistics, Inferential Analysis, and Latent Class Analysis

To carry out the proposed research, questions 11, 20, and 21 of the questionnaire (see the questionnaire in Appendix A) were used. The analysis of the results was approached, from a methodological point of view, in three stages. In the first stage, dedicated to characterizing the demand for gastronomic tourism, quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Measures of centrality and dispersion were used to characterize the distribution of responses. Qualitative data were subjected to content analysis to categorize emerging themes and recurring patterns. Coding and categorization were carried out systematically to capture the perceptions and experiences shared among respondents.

In a second stage, we move beyond descriptive statistics, introducing inferential statistical techniques. This will allow us to determine whether the differences observed between sociodemographic groups are statistically significant, in addition to testing Hypothesis 1 and evaluating broader sociodemographic patterns in gastronomic tourism behavior.

Finally, in a third stage, the goal of which was aimed at segmenting the international demand for gastronomic tourism, latent class analysis (LCA) was applied. This is a statistical technique used to study the existence of one (or more) latent variables (i.e., not directly observable) from a previous set of variables [34,35,36]. In this research, LCA was used to find different types of gastronomic tourists. The software used to perform all operations was MPlus v8.7 [37].

It is recognized in the reviewed scientific literature [38,39,40], among others, LCA is a very useful tool for market segmentation, demonstrating that it can surpass the results obtained with traditional cluster analysis techniques.

In the specific case of tourism research, LCA has been recognized as a valid statistical tool with interesting potential for classifying tourists into segments and providing a description of the characteristics of each segment [41]. LCA has been commonly used since the early 2010s to analyze various aspects of tourism. To cite only a few of the initial contributions in this field, Ref. [35] were pioneers in applying LCA in tourism, identifying different segments of cultural tourists and analyzing their behavior; Ref. [42] examined the possibilities of off-season tourism to improve Rimini’s cultural offer; and Ref. [43] used LCA to study the relationships between cultural consumers and attractions, concluding that tourists’ characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, and lifestyles influence their choice of attractions.

More recently, among other aspects, LCA has been used to segment gamblers into mutually exclusive groups according to their perceived values, satisfaction, and likelihood of returning to the destination [44] to analyze tourists’ preferences when booking hotels [45]; to study tourists’ preferences for socially responsible and environmentally friendly solutions for sustainable whale-watching management [46]; to segment and predict prosocial behaviors among tourists [47]; or to understand tourists’ behavior towards overcrowding and their choice of location, enabling destination managers to make recommendations to avoid overtourism [48].

Finally, it is important to highlight that this research was conducted in accordance with established ethical standards, ensuring both the confidentiality and anonymity of all participants. In sum, this study offers a robust and comprehensive framework for the identification of the global profile of gastronomic tourists.

Before applying the various proposed methodologies, the integrity and cleanliness of the data were verified, as well as the control for Common Method Variance (CMV). The results of all these analyses are presented in Appendix B. Specifically, regarding the control of Common Method Variance (CMV), we applied Harman’s one-factor test to assess the explanatory power of a single factor using a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) without rotation on the items. Sampling adequacy was excellent (KMO = 0.935), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 4425.466; p < 0.001), supporting the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The first component yielded an eigenvalue of 8.322 and accounted for 46.23% of the total variance, which is below the 50% threshold established by Harman. This indicates that common method variance is not a critical issue in our study. Extraction communalities ranged from 0.454 to 0.726, showing that most items are adequately represented by this factor. The rest of the results can be found in the appendix.

4. Results

4.1. Demand for Gastronomic Tourism: Descriptive Analysis

The sociodemographic characteristics of the survey (Table 1) show that the most common profile of a gastronomic tourist tends to be middle-aged adults with higher education levels and stable economic income.

The questionnaire included questions to understand respondents’ behavior, willingness to pay, expectations, and experiences. The main findings are summarized below. A significant portion of tourists shows a positive inclination toward culinary exploration as a motivation for choosing a destination. For 28.7%, the gastronomic offer significantly influences their choice (rating 5 on a 7-point Likert scale); for 19.2%, it greatly influences it (rating 6), and, for 18.1%, it is decisive (rating 7). Additionally, 53.2% have taken at least one trip exclusively for gastronomic reasons.

Regarding the most valued factors in these trips, “Interest in local gastronomy (identity)” is the highest rated, followed by “Variety in the gastronomic offer” and “Value for money.” Tourists also value the reputation, ambiance, authenticity, cultural context, and culinary excellence of their experiences.

Motivations such as “Cultural enrichment,” “Enjoying gastronomy,” and “Experiencing new things” were the most appreciated. The combination of these three motivations was the most frequent (17.6%). Gastronomic tourists seek exclusive and authentic experiences, which are difficult to replicate elsewhere. They prefer activities in production environments and recognize the appeal of a product’s fame, although it is not the main factor. Health and quality are also important, especially for tourists with dietary preferences.

A significant 86.5% consult the Internet for recommendations or reviews, and 79.8% affirm that these significantly influence their final decision. Still, recommendations from family and friends are the main information source (12.4%), followed by TripAdvisor and Booking (11.2%), official destination websites (10.7%), social media (10%), Google reviews (9.7%), and blogs or travel magazines (9%). Travel agencies were mentioned by 5%.

Regarding timing, 80.8% engage in gastronomic tourism during holidays, 54.2% on weekends, and 20.2% during weekdays. Frequency-wise, 43.7% travel for gastronomic purposes once a year, 36.1% two or three times a year, and 20.2% more than three times a year. Preferred activities include “Eating or drinking in restaurants,” “Learning about specific products or techniques,” and “Visiting food markets.” These often combine with tasting or cooking workshops, reflecting a desire to expand culinary knowledge and skills. Moreover, 12.1% enjoy exploring the destination, 10.9% visit cultural sites, 10.5% engage in nature activities, 9.3% visit friends or family, and 8.6% dedicate time to shopping and leisure.

While 53% share their experiences on social media, 45.8% do not—likely due to a preference for privacy or less interest in digital sharing. In terms of willingness to pay, there is a clear preference for mid-range experiences, with notable interest in premium options. Tasting menus performed better in higher spending ranges. In contrast, visits to food industries and cooking workshops had lower willingness to pay. Only a small group showed no interest in buying local products.

A high level of commitment (74.3%) was found toward experiences that connect with local culture and support the local economy. Still, 22.3% reported no direct interaction with local producers. While 72% are willing to participate in local activities, 25% are not—likely due to time constraints or personal preferences.

When asked how much more than their usual budget they would pay for specific activities, 23% wouldn’t pay more for “Cooking classes and workshops”; 12% for “Gastronomic routes”; and 14% for “Gastronomic events” or “Meals in local homes.” However, 25% would pay slightly more for workshops and events. Between 36% and 46% of respondents would pay moderately more across all activities.

Between 11% and 13% would pay significantly more for “Exclusive gastronomic experiences,” “Market and producer visits,” and “Experiencing traditional local cuisine.” Between 11% and 36% expressed willingness to invest significantly more across the board—indicating strong overall interest in gastronomic experiences.

When asked about willingness to pay more based on specific factors, tourists showed moderate commitment to paying more for traditional cuisine, authentic spaces, community interaction, and sustainable products. Vegetarian and vegan options were less appealing, with nearly half unwilling to pay extra.

In terms of satisfaction, 66.9% were in positive categories: “Satisfied” (31.1%), “Very satisfied” (35.4%), and “Completely satisfied” (15.4%). However, 17.2% were neutral or dissatisfied. There was strong interest in acquiring or recommending quality-certified gastronomic products, such as olive oil, wine, ham, or cheese. A total of 79% expressed a probability between moderate and very high, with 35.2% indicating “Very high probability” and 23.3% “Very likely.”

Regarding the budget, 23% of respondents have a maximum budget of EUR 200 per trip; 17% budget between EUR 201 and EUR 500; 14% between EUR 501 and EUR 2000; and 3.65% between EUR 2001 and over EUR 3000. This highlights a diversity of financial capacities among gastronomic tourists. In terms of average daily spending, 32.54% reported spending between EUR 30 and EUR 100; 12.11% between EUR 101 and EUR 200; 11.40% less than EUR 30; and a small group reported spending more than EUR 200 per day. This confirms a heterogeneous profile in economic behavior and spending preferences within gastronomic tourism.

4.2. Inferential Analysis

Understanding the determinants of willingness to pay for gastronomic experiences is crucial for designing effective and targeted strategies in the tourism economy. Inferential statistics allows researchers to go beyond descriptive trends, identifying whether observed differences between sociodemographic groups are statistically significant. This section applies robust analytical techniques to test hypothesis 1 and evaluate broader sociodemographic patterns in gastronomy tourism behavior.

4.2.1. Influence of Sociodemographic Factors on Willingness to Pay

To test hypothesis 1, an analysis was conducted to identify significant differences among sociodemographic profiles in their willingness to pay for gastronomic experiences. A composite variable, SUM_Q20_Q21 (the sum of all scores from Q20 and Q21, ranging from 0 to 90), was constructed. Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied for nationality, age, occupation, educational level, and income; the Mann–Whitney U test was used for gender; and Spearman’s correlation was performed with the sociodemographic variables. These inferential tests complement the original descriptive percentages and fully address the methodological concern raised.

Regarding the influence of sociodemographic variables on the willingness to pay for sustainable initiatives related to gastronomic tourism, the Spearman correlation analyses and the Kruskal–Wallis test provide a complementary perspective. Spearman’s coefficients reveal significant associations between various sociodemographic variables and the individual willingness-to-pay items (Q20 and Q21). The findings obtained allow us to draw the following conclusions: (i) Age and monthly net income show significant positive correlations with most of the items in Q20 and Q21, as well as with the total sum (SUM_Q20_Q21; ρ = 0.130 and ρ = 0.178, respectively; p < 0.01). (ii) Occupation also shows positive associations with several items, particularly Q20_3 to Q20_7 and Q21_1 to Q21_4. (iii) Nationality presents more specific relationships, with both positive (Q20_1, Q20_5, Q20_8) and negative (Q20_7, Q20_9, Q21_1, Q21_2) significant correlations. (iv) Gender and educational level show weaker and more item-specific associations, although gender is significantly associated with Q20_1, and educational level with Q21_1 and Q21_2.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess overall differences between sociodemographic groups in the aggregated score SUM_Q20_Q21. The findings obtained allow us to draw the following conclusions: (i) Monthly income level is the only variable with statistically significant differences between groups (H = 16.46; df = 7; p = 0.021), with a small to moderate effect size (η2 = 0.025). (ii) Age, nationality, occupation, and educational level show trends approaching significance (p < 0.10), suggesting a potential influence that may become more evident in larger samples. (iii) Gender does not show significant differences in the dependent variable (p = 0.585), nor a meaningful effect size (η2 = 0.001).

Taken together, these results reinforce the idea that income is the most decisive factor in the willingness to pay for gastronomic-sustainable initiatives, both at the individual and aggregate levels. Other factors such as age, nationality, or occupational status may play a secondary role, although their impact appears to be more limited or dependent on the specific context of the item evaluated.

To assess the joint influence of sociodemographic variables on demand, a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with a normal distribution and identity link function was estimated, using the continuous variable SUM_Q20_Q21 as the dependent variable. The predictors included were age, gender, monthly income, nationality, occupation, and educational level.

The omnibus test showed that the model significantly improves upon the intercept-only model (χ2 = 42.15; df = 24; p = 0.012), and the Deviance/df ratio was 1.06, indicating a good fit. The information criteria (AIC = 3309; BIC = 3414) support the parsimony of the model. The results show that (i) European nationality, compared to Spanish nationality, is associated with a significant reduction of 3.8 points in willingness to pay extra (B = −3.84; p = 0.037); (ii) women score, on average, 2.6 points higher than men (B = +2.64; p = 0.037); (iii) income has the most pronounced influence: individuals earning less than EUR 600 per month score significantly lower than those earning between EUR 2100 and EUR 3000 (−6.92 points; p = 0.021) or more than EUR 3000 (−10.24 points; p = 0.001); and (iv) age, educational level, and occupation do not reach statistical significance (p > 0.005).

Consequently, the original wording of hypothesis 1 is considered appropriate, as there is now sufficient empirical evidence—based on correlations, group comparisons, and a predictive model—to support the existence of sociodemographic relationships and influences on willingness to pay.

4.2.2. Identification of Significant Differences Between Sociodemographic Profiles or Groups

This section examines whether there are significant differences between sociodemographic profiles across two key dimensions: (i) willingness to pay for gastronomic experiences (Q20 and Q21), and (ii) frequency of gastronomic travel (Q11).

To this end, non-parametric tests were applied, in line with the ordinal nature of the data and the lack of normality: Kruskal–Wallis tests for factors with three or more categories (nationality, age, occupation, educational level, income), Mann–Whitney U tests for the gender factor, and, when the frequency variable (Q11) was analyzed as proportions across response categories, chi-square tests of independence (with Cramér’s V as the effect size). Each test reports the test statistic, significance (p-value), and effect size (η2 for Kruskal–Wallis; Rosenthal’s r for Mann–Whitney; Cramér’s V for χ2), in order to assess the practical relevance of the observed differences. In this way, the following tables complement the descriptive percentages with robust inferential evidence that fully addresses the methodological concern raised.

Inferential analyses confirm that nationality and monthly income level are the most consistent predictors of willingness to pay (Q20) and attribute valuation (Q21). For nationality, significant differences were found in five Q20 items and two Q21 items (p ≤ 0.01), with effect sizes ranging from η2 = 0.025 to 0.077. Specifically, travelers from outside Europe show a higher willingness to pay for culinary experiences and place greater importance on gastronomic authenticity than Spanish and European respondents.

The income variable revealed significant differences in six Q20 items and two Q21 items (p ≤ 0.01). Three of these showed moderate effect sizes (η2 ≈ 0.07–0.09), indicating that participants with monthly incomes above EUR 3000 are clearly more willing to pay beyond their usual budget and place greater value on the premium attributes of the experience.

Regarding age, differences were observed in six items (p ≤ 0.05), with small effect sizes (η2 ≈ 0.013–0.046). The 26–35 and 36–50 age cohorts demonstrated the highest willingness to pay and the strongest valuation of attributes, while respondents over 50 showed lower economic inclination.

Occupation also explains variation in six items: two in Q20 (η2 ≈ 0.034–0.056) and two in Q21 (η2 ≈ 0.048–0.067). Service professionals and executives stand out for their higher spending potential and stronger preference for exclusive experiences, compared to students and retirees.

Educational level, in turn, shows significant but modest effects in Q20_7 and Q21_1–Q21_2 (η2 ≈ 0.015–0.022). As education increases, there is a slight rise in willingness to pay for gastronomic routes and in the importance assigned to exclusive experiences.

Mann–Whitney U tests indicate that gender has minimal influence on the results: differences are found only in Q20_1 (r = 0.170) and Q21_8 (r = 0.097), with small effects suggesting a slightly higher preference among women for cooking workshops and visits to local markets.

Regarding the frequency of gastronomic travel (Q11), the chi-square test shows that age and income are the only factors with significant differences: age (χ2 = 18.694; df = 6; p = 0.005; V = 0.149) and income (χ2 = 30.525; df = 14; p = 0.006; V = 0.190) both present moderate effect sizes. These results suggest that respondents aged 26–50 and those reporting monthly incomes above EUR 3,000 travel more frequently for gastronomic purposes. In contrast, nationality, gender, occupation, and educational level show no significant associations with travel frequency (p > 0.05; V ≤ 0.116), suggesting a relatively homogeneous travel pattern across these groups.

In summary, statistically significant differences are concentrated in the income and nationality factors, followed by age and occupation, while gender and, to a lesser extent, educational level have limited impact. Most effect sizes are small, so the findings should be interpreted with caution and validated in future studies that simultaneously control for these covariates.

4.3. Segmentation of Demand for Gastronomic Tourism

Although the survey includes many more questions, to apply LCA (Latent Class Analysis) and identify profiles of individuals who engage in gastronomic tourism, it was decided to consider question number 12 (renamed for this study as Q3) from the questionnaire, titled “What gastronomic tourism activities do you prefer to do at a destination?”. This is a multiple-choice question that breaks down into ten sub-questions, dichotomous variables that take the value 1 if the respondent answers affirmatively to the proposed gastronomic activity and the value 0 if the response is negative. Then, the ten possible responses that interviewees could select in this question are correlated, which are ultimately the variables used for the latent classes.

Table 2 shows the evolution of fit criteria as the number of classes increases. As observed, using statistical criteria, the best solution is three profiles or classes, although interpretive criteria can also be used. The other solutions (two or four classes) could also be good. Consequently, the selection of three segments is chosenmade.

Table 2.

Fit criteria for selecting the number of classes.

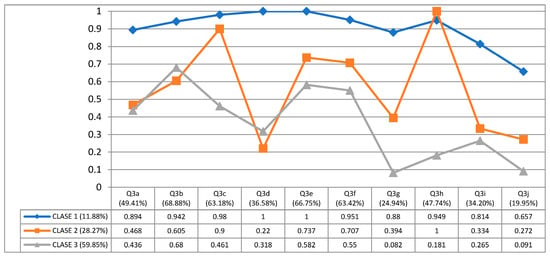

Table 3 presents the indicators of the conditional probabilities that each gastronomic tourism activity is present in each of the three latent classes identified in the analysis. The classes differ in terms of the activities that tourists prefer to do at a destination. Below is the interpretation for each class:

Table 3.

Indicators of gastronomic tourism activities by latent class.

Class 1 (11.88% of the sample): Tourists in this class have a high probability of preferring activities such as eating or drinking at production sites (98%), restaurants (94.2%), or other places like street ventures (100%), visiting gastronomic markets (100%), and buying local products (95.1%). Additionally, these tourists show a strong inclination towards authentic and high-quality gastronomic experiences, such as visiting wineries, industries, or thematic museums (94.9%) and learning about specific products or techniques (89.4%). On the contrary, they show less interest in participating in cooking workshops or courses (65.7%).

Class 2 (28.27% of the sample): Tourists in this class mainly prefer visiting wineries, industries, or thematic museums (100%), as well as eating or drinking at production sites (90%). They also have a high probability of buying local products (70.7%) and visiting gastronomic markets (73.7%). However, they show less interest in participating in cooking workshops or courses (27.2%) and eating or drinking at other places (22%).

Class 3 (59.85% of the sample): This class, which constitutes the largest proportion of the sample, has a considerable probability of preferring to eat or drink in restaurants (68%), visit gastronomic markets (58.2%), and buy local products (55%). However, they show less interest in specialized activities, such as cooking workshops or courses (9.1%) and participating in tastings or samplings (8.2%).

It is important to consider the entropy value obtained, as it measures the level of uncertainty or mixing between the identified classes. In this manner, an entropy of 0.817 suggests that there is a good separation between the three latent classes selected through the analysis. This means that the individuals in the sample are relatively clearly grouped into one of the three classes, with little ambiguity, implying that the model is reliable.

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the behavior of the three selected latent classes. This graph shows the variation of the indicators from Table 3, illustrating the differences in gastronomic activity preferences among the latent classes. Thus, it is observed that Class 1 is distinguished by a high probability of participating in a wide variety of gastronomic activities, especially those that are more specialized and diverse; Class 2 shows a balance between common and exclusive activities, with a particular focus on visiting wineries, industries, or thematic museums; and Class 3 focuses more on common and accessible gastronomic activities, such as eating in restaurants and buying local products.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the three selected classes. Source: Authors’ own.

To characterize each of these three classes, the latent classes were crossed with the following variables: gender, age, education level, profession/occupation, income level, and the number of times they engage in gastronomic travel per year.

The corresponding Chi-2 tests were performed. All the crosses were significant (p-values < 0.05), except for the gender variable, indicating, therefore, dependency between the classes and the crossed socio-demographic variables, except for the mentioned gender variable.

To propose the characterization of the latent classes presented below, the corresponding tables of observed and expected frequencies were analyzed. From this analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn.

Class 1—High-quality gastronomic tourists: This cluster contained a total of 50 respondents, representing 11.88% of the sample. In general, the gastronomic tourists in this cluster are characterized by being older, having higher incomes, having the highest education levels, traveling more frequently, and being professionals such as freelancers and others (e.g., civil servants, teachers, etc.). It can be concluded that this is the most “select” class, with fewer individuals.

Regarding the question used to select the classes or profiles, referring to the activities these tourists prefer to do at a destination, it is worth noting that this class has a high probability of participating in almost all gastronomic activities, which suggests a strong interest in varied and specialized gastronomic experiences.

Class 2—Gastronomy enthusiast tourists: This cluster contained a total of 119 respondents, representing 28.27% of the sample. These are gastronomic tourists of middle and older age, with from medium to high incomes, university education levels, and professions such as business owners, high-level managers, retirees, and others.

This class shows moderate interest in various activities, with a particular focus on visiting wineries, industries, or thematic museums. Therefore, their preferences particularly highlight educational activities and visits to production sites.

Both classes, C1 and C2, share similar attitudes toward activities such as “Eating or drinking at production sites (wineries, vineyards, plants, etc.)” and “Visiting wineries, industries, or thematic museums,” as their socio-economic profiles may be similar.

Class 3—Casual gastronomic tourists: This cluster contained a total of 252 respondents, representing 59.85% of the sample. These are the younger tourists, with a high percentage of students, non-university education levels, lower incomes, and they travel less frequently. This class, the largest, primarily prefers more common and accessible gastronomic activities, showing less interest in specialized activities that require a greater commitment of time or resources.

This study contributes novel insights to the gastronomic tourism literature by analyzing observable behaviors rather than solely relying on self-reported motivations, thereby broadening the methodological approach and providing a solid basis for international comparisons. As the findings align with results in other contexts, they are generalizable, supporting the development of evidence-based tourism policies.

The identified profiles enable destinations to tailor their offerings based on the level of specialization, authenticity, and accessibility required by each segment—an essential capability in a competitive environment where travelers seek personalized experiences with added value.

Class 1 represents a high-value segment both economically and symbolically, aligned with sustainable tourism, which strengthens destination branding and fosters innovation. Class 2 is strategic for rural or emerging destinations, as it allows for leveraging agri-food heritage without major investment, promoting seasonality reduction. Class 3, despite lower spending, democratizes gastronomic tourism and enhances visibility through social media, making it particularly relevant for urban and short-break destinations.

These profiles reflect global trends: Class 1 is associated with experiential luxury and slow tourism; Class 2 with creative and learning-based tourism; and Class 3 with urban and digital tourism. The ability of destinations to segment and design experiences that align with these values will be key in an increasingly demanding and experience-oriented market.

5. Discussion

Unlike the usual scientific literature on the demand for gastronomic tourism (which identifies common aspects and shows a limited understanding of the topic), this study makes an effort to characterize the gastronomic tourist at an international level, with the particularity that it focuses on the gastronomic tourists themselves.

To date, the studies conducted on the characterization of gastronomic tourism demand have adopted a fragmented approach, focusing on specific regions, cultures, or territories. While these studies provide a general insight into the demand profile, their limited scope hinders the extrapolation of findings and constrains the understanding of how various factors interact across diverse global contexts. In the case of studies that address market segmentation in gastronomic tourism, they show varied approaches and criteria, making it difficult to create clearly defined segments [49]. This study identifies the need to apply a more robust and universal model that allows for precise segmentation and is applicable to different tourism contexts.

This same difference sets this study apart from existing studies based on cross-sectional data (specific moments), which limit the ability to understand how demand profiles evolve over time and under different circumstances [50]. The data obtained in this study highlight the need for longitudinal analyses to observe the changes and trends required by the dynamic vision of gastronomic tourism.

Regarding the demographic characteristics of the demand, existing studies are limited to showing the age range and, in some cases, levels of education and available income [51]. Others highlight the consumption behavior of gastronomic tourists, showing a tendency to spend more on food and beverages compared to other types of tourists [50], and certain activities that show interest beyond the act of eating [52]. This study concretely presents the three predominant profiles of gastronomic tourists, along with their support and specialized analysis.

The literature mostly shows case studies that reveal a multifaceted panorama and certain segments of gastronomic tourists based on their motivations, demographic characteristics, and consumption behaviors in specific destinations. These studies recognize that gastronomic tourists are driven by diverse motivations, such as the search for authenticity and unique experiences that connect them with the identity of the destination they visit [53]; hedonism and the pursuit of sensory pleasure through tasting food and beverages [49]; the desire to learn and expand personal culinary knowledge [43], among others.

Therefore, with this information, a unified theoretical framework of universal application is created, facilitating the comparison and synthesis of studies by leaving aside the use of various categories and terminologies to describe gastronomic tourists and the influence of specific contexts.

From a theoretical perspective, the findings of this research reinforce and expand existing theories on experiential practices among gastronomic tourists by demonstrating the influence of sociodemographic factors on travel and gastronomic consumption decisions. Furthermore, they validate the notion of market heterogeneity and provide an empirical basis for predictive behavior models.

In practical terms, the segmentation carried out allows for the development of differentiated strategies: exclusive and educational experiences for high-spending tourists; accessible offerings for occasional tourists; and intermediate products for enthusiasts. This information creates clear opportunities for designing robust policies aligned with the motivations and capacities of each profile.

Integrating this data into tourism intelligence systems strengthens planning, enhances destination competitiveness, and positions gastronomic tourism as a key driver of local development.

The findings of this study enrich existing theoretical frameworks on consumer behavior in experiential tourism by demonstrating how sociodemographic and motivational factors interact to shape distinct demand profiles. The proposed typology, internationally applicable, overcomes the contextual limitations of previous models and reinforces theories centered on the search for authenticity, sensory pleasure, and learning. In practical terms, the results support the design of differentiated gastronomic experiences tailored to each segment and guide tourism planning toward more effective strategies for marketing, decentralization, and sustainability. Integrating this model into tourism intelligence systems would facilitate trend monitoring and adaptive policy-making, thereby strengthening the competitiveness of gastronomic tourism at the territorial level.

On the other hand, the results of this study also invite a reconsideration of gastronomic tourism as a strategic channel for invigorating local value chains, strengthening the interaction between producers, chefs, entrepreneurs, and tourist destinations. From this perspective, gastronomy transcends its recreational function to become a vehicle for inclusive territorial development and social cohesion. Furthermore, the precise identification of tourist profiles fosters co-creation processes between visitors and host communities, contributing to cultural rootedness and a more authentic narrative of the destination. This relational approach, centered on shared experience, opens new opportunities to diversify the tourism offer and enhance its resilience against seasonality and saturation in traditional markets.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study provide a comprehensive overview that significantly contributes to the scientific literature on the demand for gastronomic tourism, as well as to the delineation of evidence-based strategies, thanks to the methodology used, allowing for a robust analysis and the appropriate generalization of the findings.

It is demonstrated that the demand for gastronomic tourism is influenced by socio-economic and cultural variables that are correlated and generalizable. Likewise, the characteristics and preferences of each identified class of gastronomic tourists are detailed: a first class with a high preference for diverse and specialized gastronomic experiences; a second class with moderate interest in gastronomic tourism, focused on educational activities and visits to production sites; and a third class that prefers common and accessible gastronomic activities. It is worth noting that the resulting entropy value clearly grouped the three classes, which shows that this study presents a reliable model.

By identifying differentiated profiles specific to gastronomic tourism, the planning and management of destinations that focus on this type of tourism is facilitated, as well as the design of effective strategies, tourist satisfaction, and the promotion of the much sought-after sustainable economic development. Therefore, the hypotheses established in this study are validated.

The information gathered identifies profiles of gastronomic tourism at an international level; this is the fundamental difference compared to other studies that characterize tourists in specific destinations; therefore, this study has universal validity.

The identified profiles provide concrete tools for tourism planning and management based on actual demand: (i) in terms of experience, they help optimize the design and management of tourism products; (ii) in marketing, segmentation enables targeted campaigns through the most suitable channels and storytelling tailored to each group; (iii) in product management, these profiles support the decentralization of tourist flows, the reduction of seasonality, and the development of products aligned with visitors’ values and expectations; and (iv) in governance, they contribute to fostering public-private partnerships and professionalizing the tourism offer.

Regarding the limitations of this research, one might question whether the sample can be considered fully representative at a global level, given the absence of a universal sampling frame for “gastronomic tourists” on which to apply conventional probabilistic techniques. Consequently, it is unfeasible to define and encompass an exhaustive target population on a worldwide scale.

It is important to acknowledge the trade-off between territorial diversity and the risk of self-selection inherent in online recruitment. To mitigate this bias, the first question acted as an eligibility filter, confirming that 96.9% of participants indeed plan their trips around gastronomy.

Although an internal sampling error of ±4.8% was calculated, it must be emphasized that this value solely describes the precision of the sample and is not used to infer global population proportions. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted as exploratory and analytical—aiming to identify profiles and behavioral patterns through Latent Class Analysis (LCA)—rather than as globally representative estimates.

A clear precedent for this approach is the study by [54]. The authors selected 27 key stakeholders (chinampa producers, restaurateurs, promoters, tourists, and academics) through purposive and convenience sampling, justifying this choice due to the lack of a census framework for visitors. They addressed data collection using non-probabilistic strategies similar to those applied in our study.

For future research in this aspect, we recommend future replications using regional probabilistic panels and longitudinal designs to validate the proposed typology and examine the temporal stability of the identified segments.

Another limitation that should be considered is that, in the inferential analysis conducted to determine whether significant differences exist among sociodemographic groups, such differences were indeed demonstrated. However, some of the effect sizes are small, which calls for cautious interpretation of certain conclusions. For future research, it would be advisable to confirm these differences using statistical techniques that allow for the simultaneous control of these covariates.

The most recent literature delves into the link between gastronomic tourism and sociocultural variables (beliefs, identity, language, social roles, status, etc.). Variables of this type were not considered in this study. This could be acknowledged as a limitation that encourages future research that is more representative, longitudinal, and employs mixed approaches.

Author Contributions

C.B.-N.: investigation, methodology, conceptualization, writing-original draft. J.I.P.-F.: investigation, methodology, conceptualization; formal analysis; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because this research does not involve studies on human beings that include the use of human biological samples, animal experimentation, handling of biological agents, or the use of genetically modified organisms.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Appendix A and Appendix B.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Survey to determine the behavior of gastronomic tourists

BEHAVIOR, WILLINGNESS TO SPEND, EXPECTATIONS, AND EXPERIENCES

- Q1.

- When you travel for holidays, do you show interest in getting to know the gastronomy from the places you visit?

- Yes

- No

- Q2.

- To what extent does the gastronomic offer influence when choosing a destination for your visit? (Likert scale: 1it does not influence at all; 7 it influences a lot)

| Does not influence at all | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | It influences a lot |

- Q3.

- Have you ever made a trip with the only purpose of enjoying the gastronomic offer of this destination?

- Yes

- No

- Q4.

- If you are influenced by the gastronomic offer when choosing a destination, what factors do you value most about this offer? (Likert scale: 1 the least rated; 7 the most rated)

| Assessment (1 to 7) | Factors |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

- Q5.

- What is your motivation for gastronomic tourism activities? (multi-response)

- The very act of traveling

- Cultural enrichment

- Enjoying the gastronomy

- Having new experiences

- Getting out from the routine

- Work

- Shopping & Leisure

- Other

- Q6.

- Which of the following factors motivate you the most when trying the gastronomy of a destination? (Likert scale: 1 motivates the least; 7 motivates the most)

| Assessment (1 to 7) | Factors |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

- Q7.

- Do you usually search the internet for recommendations/reviews before going to a gastronomic establishment?

- Yes

- No

- Q8.

- If the answer to the previous question is “Yes”, do the comments / reviews you read on internet really influence you when choosing the establishment you finally attend?

- Yes

- No

- Q9.

- What are the information sources consulted prior to your arrival at your destination? (multi-response)

- Destination’s official website

- Family and friends’ recommendations

- Review websites (Tripadvisor, Booking, and others)

- Google reviews

- Social media

- Travel blogs & magazines

- Travel agencies

- Doesn’t look for information before arriving at the destination

- Q10.

- What are the periods of time you allocate for gastronomic tourism? (multi-response)

- Weekdays

- Weekends

- Holidays or vacations

- Q11.

- How often do you go on gastronomic trips?

- Once a year

- Two or three times a year

- More than three times a year

- Q12.

- What are the gastronomic tourism activities that you prefer to do in a destination? (multi-response)

- Learn about specific products or techniques

- Eating or drinking in restaurants

- Eating or drinking at production sites (wineries, vineyards, plants, etc.)

- Eating or drinking in others (street entrepreneurships, etc.)

- Visiting food markets

- Buying local products

- Carrying out tastings

- Visiting wineries, industries or themed museums

- Attending gastronomic events

- Workshops or cooking courses

- Other. …………………………………………………………………

- Q13.

- When you do gastronomic tourism, what complementary activities do you do? (multi-response)

- Visiting the destination (population centers, cities, communities)

- Visits to cultural sites

- Visits to family or friends

- Nature activities

- Health & Wellness Activities

- Shopping & Leisure

- Rest

- Other. …………………………………………………………………

- Q14.

- When you do food tourism, do you share your opinion or experience on social media?

- Yes

- No

- Q15.

- When you do food tourism, how much are you willing to spend on the following activities:

| I would not spend anything | I would spend less than 10 € | I would spend 11 to 20 € | I would spend 21 to 35 € | I would spend 36 to 50 € | I would spend 51 to 100 € | I would spend 101 to 150 € | I would spend more than 150 € | |

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

|

- Q16.

- When you do gastronomic tourism, do you interact directly with local producers?When you do gastronomic tourism, do you interact directly with local producers?

- Yes

- No

- Other. …………………………………………………………………

- Q17.

- When you do gastronomic tourism, do you actively participate in the activities offered?

- Yes

- No

- Other. ………………………………………………………………….

- Q18.

- When visiting a tourist destination, are you worried that you won’t find vegan or vegetarian food options? (Likert scale: 1 it does not worry you at all; 7 it worries you extremely)

| It does not worry you at all | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | It worries you extremely |

- Q19.

- How decisive is it that you have a vegan or vegetarian food offer to choose or discard the destination? (Likert scale: 1 not at all determinant; 7 totally determining)

| Not at all determinant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Totally determining |

- Q20.

- When you do gastronomic tourism, to what extent would you be willing to pay more, compared to what is usually your budget, to enjoy a gastronomic experience?

| 1 Nothing | 2 A Little | 3 Moderate | 4 Plenty | 5 A lot | |

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

|

- Q21.

- When you do gastronomic tourism, to what extent would you be willing to pay more, compared to what is usually your budget for enjoying a gastronomic experience based on:

| 1 Nothing | 2 A Little | 3 Moderate | 4 Plenty | 5 A lot | |

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

|

- Q22.

- Overall, what is your level of satisfaction with the gastronomic tourism experiences you have enjoyed lately? (Likert scale: 1 not at all satisfied; 7 totally satisfied)

| Not at all satisfied | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Totally satisfied |

- Q23.

- If, during your trips, you have tasted any gastronomic product with quality seals (olive oils, wines, ham, cheese, etc.), indicate how likely (Likert scale: 1 no probability; 7 strongly probable) you are to buy (or recommend) it later for home consumption.

| No probability | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | (Strongly probable) you are to buy (or recommend) it later for home consumption. |

- Q24.

- What is the usual average budget of a food tourism trip for you?

- Q25.

- What is the usual average DAILY expenditure of a gastronomic tourism trip for you?

- SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

- Q1.

- Nationality

- Q2.

- Place of habitual residence

- Q3.

- Age

- 18–24 years old

- 25–40 years

- 41–56 years

- 57–75 years

- 76–91 years

- Q4.

- Gender

- Male

- Female

- Other (specify):

- Q5.

- Profession—Occupation

- Student

- Professional free practice

- Employee—Operator

- Employee—Middle management

- Businessman—High Command

- Household chores

- Unemployed

- Retired

- Other (specify)

- Q6.

- Level of Education

- No education

- Primary school

- High school

- Undergraduate degree

- Master’s degree

- Doctorate degree

- Q7.

- Monthly Net Income

- <600€

- 600€–900€

- 900€–1200€

- 1200€–1500€

- 1500€–1800€

- 1800€–2100€

- 2100€–3000€

- 3000€ or more

- NOTE: The process of conducting this survey and the subsequent data analysis fully complies with “Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights (https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2018–16673)” accessed on 26 January 2024.

Appendix B. Confirmation of Data Integrity and Cleanliness, and Control of Common Method Variance

Prior to the application of the various proposed methodologies, this section addresses the confirmation of the integrity and cleanliness of the data used, as well as the control for Common Method Variance (CMV).

Regarding data integrity and cleanliness, the internal reliability of the questionnaire was first confirmed by analyzing the internal consistency of each scale using Cronbach’s alpha. This measure assesses the extent to which the items within a given scale consistently reflect a single underlying construct. High alpha values (≥ 0.70) indicate that the responses are coherent and that participants have interpreted the items designed to measure the same concept in a consistent manner. The results obtained (0.878 for Q20; 0.914 for Q21; and 0.929 for the global scale) support the integrity of the data by confirming the reliability of the measurements and ruling out excessive noise, thereby fulfilling the reviewer’s requirement to verify data quality.

Subsequently, to detect outliers and missing data, all variables were examined for missing values, and none were found (0% of cases with missing data). This complete absence confirms the integrity of the observation matrix, eliminates bias due to imputation, and simplifies further analyses, in line with the reviewer’s request to verify data cleanliness. To assess integrity through outlier detection and case influence, two techniques were applied: (i) Mahalanobis Distance: A Mahalanobis distance was calculated by fitting a linear regression model where one item served as the dependent variable and the remaining items as predictors. This measure identifies multivariate outliers (Mahalanobis range: 0.930–92.291; threshold: χ2 with 17 degrees of freedom, p < 0.001 ≈ 48.28; observations above the threshold: 9 cases, 2.1% of the sample). (ii) Cook’s Distance: Using the same linear regression model, Cook’s distance was saved to assess the individual influence of each case on the model coefficients (Cook’s range: 0.000–0.131; practical threshold: 4/N ≈ 0.0095; observations above the threshold: 18 cases, 4.3% of the sample). After manually inspecting these atypical and influential observations, no data entry errors or inconsistent response patterns were found that would justify their exclusion. Therefore, with 2.1% of cases identified as multivariate outliers and 4.5% as highly influential observations, it was decided to retain all cases in the final analysis. This confirms the integrity and reliability of our data.

To assess the convergent validity of our constructs, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) without including a method factor, using Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation. Overall, the CFA fit was only acceptable in terms of SRMR, while CFI, TLI, and RMSEA indicated a certain degree of misfit. However, given the number of indicators and the complexity of the model, we proceeded to evaluate convergent validity through factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). The analysis of R2 and standardized loadings (λ) shows that R2 values range between 0.247 and 0.684, indicating that each factor explains more than 25% of the variance in its items. All factor loadings are statistically significant and well above 0.70, indicating strong indicators for their respective factors. Moreover, the CFA reveals high factor loadings and very high Composite Reliability (CR) values for both constructs, as well as adequate AVE for WTPatribs and near-optimal AVE for WTPtipo. Although some global fit indices fall short of the most stringent criteria, the strong values for loadings, R2, AVE, and CR robustly support the convergent validity of the scales used.

Additionally, to verify that our two constructs are conceptually distinct, we applied the [55] criterion by comparing the AVE of each factor with the squared correlation between them. In the previous CFA model, the AVE for each factor was estimated, and the standardized correlation between the two factors was obtained (r2 = 0.093). Since both AVE values clearly exceed r2, each construct shares more variance with its own indicators than with the other factor. Therefore, the discriminant validity of the scales is confirmed according to [55].

Regarding the control of Common Method Variance (CMV), we applied Harman’s one-factor test to assess the explanatory power of a single factor using a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) without rotation on the items. Sampling adequacy was excellent (KMO = 0.935), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 4425.466; p < 0.001), supporting the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The first component yielded an eigenvalue of 8.322 and accounted for 46.23% of the total variance, which is below the 50% threshold established by Harman. This indicates that common method variance is not a critical issue in our study. Extraction communalities ranged from 0.454 to 0.726, showing that most items are adequately represented by this factor.

In order to assess the potential presence of Common Method Variance (CMV) using a more sophisticated technique, we selected item Q22 (level of satisfaction with gastronomic tourism experiences) as a marker variable, given its lack of theoretical relationship with motivations or willingness to pay. With regard to the verification of the marker variable, Q22 exhibited adequate variance (M = 5.39; SD = 1.16; range 1–7), making it suitable for “absorbing” the method variance. To analyze zero-order correlations, we calculated the correlation matrix among the 18 items from Q20 and Q21, obtaining an average zero-order (off-diagonal) correlation of = 0.425. Subsequently, we computed partial correlations controlling for Q22, adjusting all 18 item correlations by the marker variable. The average partial correlation was = 0.421. The estimated percentage of variance attributable to CMV was then calculated as: %CMV = ( − )/ ≈ 0.94%. This minimal difference indicates that CMV is not a substantial concern in our data.

Ref. [56] propose a very strict threshold (< 1%) for detecting Common Method Variance. Our estimated %CMV (0.94%) falls below this threshold, indicating that the shared variance attributable to method effects is practically negligible. This confirms that the inter-item relationships are not biased by systematic response effects and supports the reliability of our constructs.

In conclusion, the minimal average decrease in correlations (only 0.004 points) after controlling for Q22 further reinforces that common method variance does not significantly bias the results of our scales.

To incorporate a method marker factor following the approach of [57], we proceeded as follows:

Definition of the model with a method factor:

- We created three latent factors: WTPtipo, loading on Q20; WTPatribs, loading on Q21; and Method, the method factor which scales its loading by fixing Q22 = 1 and also loads on all indicators from Q20 and Q21.

- We constrained the covariances between the Method factor and the theoretical constructs to zero, so that the method factor would only capture shared method variance.

Estimation: We used Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation and requested fit indices (CFI, TLI, RMSEA, SRMR).

Global fit: Although the χ2 statistic was significant, the CFI and SRMR values met the thresholds for acceptable model fit. RMSEA was 0.079 (90% CI [0.071–0.086]), just at the recommended cutoff point.

Criteria proposed by [57] A ΔCFI < 0.01 and a ΔRMSEA < 0.015 would suggest that the inclusion of the method factor does not provide a substantial improvement in model fit, thereby ruling out serious CMV bias.

ΔCFI = 0.921 − 0.920 = 0.001 (<0.01)

ΔRMSEA = 0.079 − 0.080 = −0.001 (<0.015)

Method factor loadings:

Q22 (marker): λ = 0.333 (p < 0.001)

The items from Q20 and Q21 loaded onto the Method factor with standardized estimates ranging from λ = 0.004 (Q20_1, not significant) to λ = 0.732 (Q20_7), most of them being statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Two items (Q20_1 and Q21_8) showed non-significant or very low loadings, suggesting a reduced method effect.

Validation of theoretical factors:

All indicators of WTPtipo and WTPatribs showed high and significant standardized loadings (λ = 0.323–0.769; p < 0.001), confirming convergent validity. The covariance between WTPtipo and WTPatribs was ϕ = 0.554 (p < 0.001), indicating a moderate correlation between the two constructs.

Therefore, the inclusion of the marker factor does not substantially improve model fit (ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA are below the thresholds of 0.01 and 0.015, respectively), indicating that the Common Method Variance (CMV) captured by the marker factor is minimal and does not introduce a critical bias in the model.

Additionally, to further assess the presence of Common Method Variance (CMV) without relying on an explicit marker variable, we implemented an unmeasured latent method factor model following [58]. In this approach, we defined a single model with three latent factors:

Model definition: We specified three latent factors: WTPtipo, which loads on Q20; WTPatribs, which loads on Q21; and Method, the unmeasured method factor, which loads homogeneously (with a common parameter λ) on all indicators from Q20 and Q21. The variance of the method factor was fixed at 1, and its covariances with the substantive factors were constrained to zero, ensuring it captures only method-related variance.

Estimation: We used Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation and requested fit indices (CFI, TLI, RMSEA, SRMR), as well as R2 values and standardized loadings for the indicators.

Global fit: The unmeasured common method variance model did not achieve minimally acceptable fit, suggesting that a single unmeasured factor does not plausibly explain the covariances among the items.

R2 of the indicators: Most indicators exhibited high R2 values (ranging from 0.58 to 0.83), indicating that a large portion of the variance in each item is explained by their respective theoretical factors rather than by a residual “common factor.”

The poor fit of the unmeasured latent method factor model (CFI < 0.90; RMSEA > 0.10; SRMR > 0.08), along with the high R2 values of the items, indicates that there is no single source of common method variance systematically distorting all responses. Combined with the results from the explicit marker variable analyses, this robustly confirms that CMV does not critically bias our results.

References

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Guía para el Desarrollo del Turismo Gastronómico. 2019. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284420995 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Ginés-Ariza, P.; Noguer-Juncà, E. Food in slow tourism: The creation of experiences based on the origin of products sold at Mercat del Lleó (Girona). Heritage 2021, 4, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkranikal, J. Gastronomy tourism experiences: The cooking classes of Cinque Terre. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 49, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachão, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V.; Ferreira, C. Food-and-wine tourists’ willingness to pay for co-creation experiences: A generational approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 46, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonsan, N.; Phakdee-auksorn, P.; Suksirisopon, P. Determining food attributes for measuring and evaluating a gastronomic destination’s appeal to visitors. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 1755–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basle, N. Evaluating Gastronomic Destination Competitiveness through Upscale Gastronomy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkefli, N.; Saidin, S.; Nasir, M.; Awang, Z. Exploration of the travel motivations of gastronomy tourism. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 524, pp. 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, R.; Pozzi, A. Niche Food Tourism. In Emerald Publishing Limited; Volume 1, Issue The Niche Food Tourist; Fusté-Forné, F., Wolf, E., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonson, A.; Masa, J. Gastroomicscape: Determinants of Gastronomic Tourism Experience and Loyalty. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2023, 12, 1127–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.; Castillo-Ortiz, I. A simplified approach for food traveller segmentation based on involvement. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 50, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. Analysis of the tourism demand for Iberian ham routes in Andalusia (Southern Spain): Tourist profile. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B. Food tourism research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannes, G.; Barreal, J. Attraction opportunities for enotourism among international travelers to Spanish wine PDO regions. GeoJournal 2024, 89, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, C. Nearby food and gastronomy: A rising value? Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, W.; Azinuddin, M.; Sharifuddin, N.; Ghani, H. Capitalising Local Food for Gastro-Tourism Development. Plan. Malays. 2023, 21, 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kay-Smith, M.; Pinke-Sziva, I.; Buczkowska-Gołąbek, K. The changing nature of thecultural tourist: Motivations, profiles and experiences of cultural tourists in Budapest. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2022, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Manzano, J.; Castro-Nuño, M.; Lopez-Valpuesta, L.; Zarzoso, Á. Quality versus quantity: Anassessmentf the impact ofMichelin-starred restaurants on tourism in Spain. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvado, J.; Joukes, V. Build sustainable stakeholders’ interactions around wine & food heritage: The Douro wine tourism case. J. Tour. Dev. 2021, 1, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.; Dias, Á.; Pereira, L.; Simões, A. Gastronomic Experience and Consumer Behavior: Analyzing the Influence on Destination Image. Foods 2023, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.; Carneiro, M.; Kastenholz, E. “Old world” versus “new world” wine tourism-diverse traveler profiles behaviors? J. Tour. Dev. 2020, 2020, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Prasongthan, S.; Silpsrikul, R. The structural equation model of behavioural intentions toward gastronomy tourism in Thailand. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 43, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]