“Innovatives” or “Sceptics”: Views on Sustainable Food Packaging in the New Global Context by Generation Z Members of an Academic Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Review

- General perception of sustainability.

- Perceptions and attitudes towards current food packaging practices.

- Preferences for sustainable food packaging.

- Barriers and incentives for sustainable choices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design and Data Collection

- -

- N = 14,500 (population size).

- -

- Z = 1.96 (95% confidence level).

- -

- p = 0.5 (maximum variability).

- -

- e = 0.052 (5% error).

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

| Characteristics | Ν | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 142 | 39.7 |

| Female | 216 | 60.3 |

| Age | ||

| 18–20 | 81 | 23.3 |

| 20–25 | 152 | 43.5 |

| 25–28 | 107 | 30.2 |

| Study Cycle | ||

| Undergraduate Student | 195 | 53.6 |

| Graduate Student | 120 | 32.9 |

| PhD Candidate | 49 | 13.5 |

| Working or not | ||

| Exclusively Student | 230 | 63.2 |

| Working Student | 134 | 36.8 |

| Question Code | Items of General Perception of Sustainability | Mean Value * |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | How often do you engage in environmentally friendly behaviours in your daily life? | 3.93 |

| Q2 | Are you actively seeking information about sustainable practices in food packaging? | 2.86 |

| Q3 | How familiar are you with the term ‘circular economy’ in the context of food packaging? | 3.01 |

| Q4 | Do you think companies should prioritise environmental sustainability in their packaging practices, even if it means higher costs for consumers? | 3.64 |

| Q5 | How would you rate your knowledge of the environmental footprint of different food packaging materials? | 3.24 |

| Question Code | Items of Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Current Food Packaging Practices | Mean Value * |

|---|---|---|

| Q6 | Perception of current food packaging as environmentally friendly | 3.15 |

| Q7 | Consideration of environmental footprint in purchase decisions | 3.32 |

| Q8 | Importance of clear information on packaging footprint | 3.69 |

| Q9 | Changed purchase due to sustainability concerns | 3.40 |

| Q10 | Consumer role in pushing companies for sustainable packaging | 3.90 |

| Question Code | Items of Preferences for Sustainable Food Packaging | Mean Value * |

|---|---|---|

| Q11 | Willingness to pay more for eco-friendly packaging | 3.32 |

| Q12 | Frequency of choosing products with eco-friendly packaging | 3.41 |

| Q13 | Sufficiency of sustainable packaging options in the market | 3.11 |

| Q14 | Importance of variety in sustainable packaging | 3.65 |

| Q15 | Importance of packaging that extends shelf life and reduces waste | 3.77 |

| Question Code | Items of Barriers and Incentives for Sustainable Choices | Mean Value * |

|---|---|---|

| Q16 | Likelihood to recommend sustainable food based on packaging | 3.60 |

| Q17 | Feeling sufficiently informed about packaging’s environmental footprint | 3.39 |

| Q18 | Importance of clear sustainability labels on packaging | 3.76 |

| Q19 | Trust in companies adopting transparent sustainable practices | 3.64 |

| Q20 | Importance of affordability of sustainable packaging options | 3.87 |

| Properties | Code | Communalities | Fact 1 | Fact 2 | Fact 3 | Fact 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in companies adopting transparent sustainable practices | Q19 | 0.576 | 0.759 | |||

| Importance of affordability of sustainable packaging options | Q20 | 0.542 | 0.736 | |||

| Importance of clear sustainability labels on packaging | Q18 | 0.517 | 0.719 | |||

| Importance of variety in sustainable packaging | Q14 | 0.454 | 0.674 | |||

| Consumer role in pushing companies for sustainable packaging | Q10 | 0.442 | 0.665 | |||

| Companies should prioritise environmental sustainability in their packaging practices, even if it means higher costs for consumers? | Q4 | 0.442 | 0.665 | |||

| Willingness to pay more for eco-friendly packaging | Q11 | 0.415 | 0.644 | |||

| Importance of packaging that extends shelf life and reduces waste | Q15 | 0.393 | 0.627 | |||

| Considering of environmental footprint in purchase decisions | Q7 | 0.655 | 0.809 | |||

| Changed purchase due to sustainability concerns | Q9 | 0.638 | 0.799 | |||

| Frequency of choosing products with eco-friendly packaging | Q12 | 0.532 | 0.729 | |||

| Likelihood to recommend sustainable food based on packaging | Q16 | 0.354 | 0.595 | |||

| Importance of clear information on packaging footprint | Q8 | 0.349 | 0.591 | |||

| Knowledge rate of the environmental footprint of different food packaging materials | Q5 | 0.579 | 0.761 | |||

| Familiarity with the term ‘circular economy’ in the context of food packaging? | Q3 | 0.555 | 0.745 | |||

| Feeling sufficiently informed about packaging’s environmental footprint | Q17 | 0.473 | 0.688 | |||

| Actively seeking information about sustainable practices in food packaging | Q2 | 0.389 | 0.624 | |||

| Engaging in environmentally friendly behaviours in daily life | Q1 | 0.244 | 0.494 | |||

| Sufficiency of sustainable packaging options in the market | Q13 | 0.667 | 0.817 | |||

| Perception of current food packaging as environmentally friendly | Q6 | 0.661 | 0.813 | |||

| Cronbach’s a reliability test | 0.885 | 0.823 | 0.794 | 0.816 | ||

| Eigenvalues | 5.64 | 3.21 | 2.65 | 1.94 | ||

| Percentage of variance explained | 24.3% | 17.8% | 13.7% | 7.7% | ||

| Total variance % | 63.5% | |||||

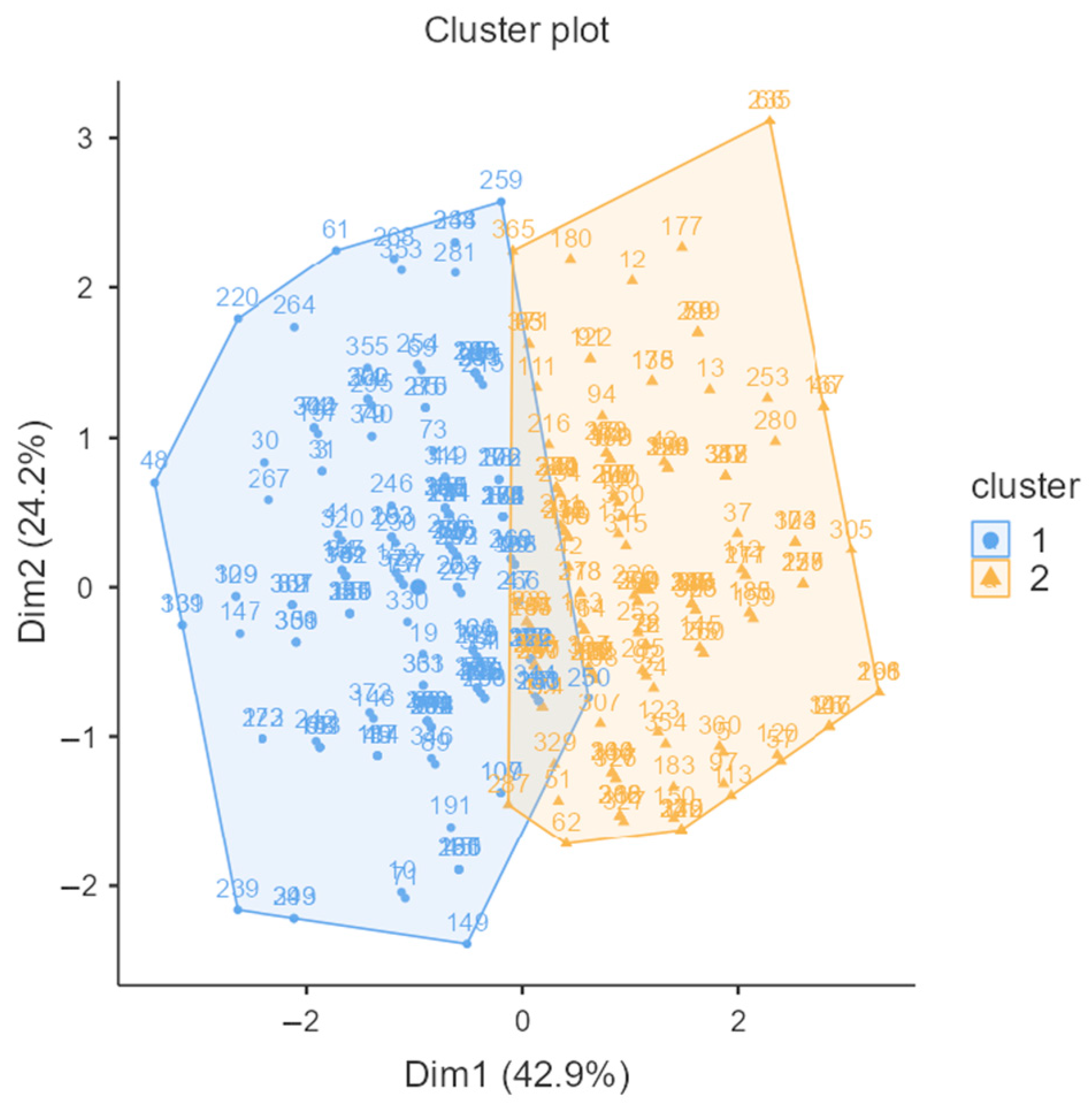

| Clusters Characteristics | Code | First Cluster: “Sceptics” | Second Cluster: “Innovators” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Sustainability-Aligned Consumer Values | |||

| Trust in companies adopting transparent sustainable practices | Q19 | 3.04 | 4.17 |

| Importance of affordability of sustainable packaging options | Q20 | 3.75 | 4.43 |

| Importance of clear sustainability labels on packaging | Q18 | 2.86 | 4.09 |

| Importance of variety in sustainable packaging | Q14 | 2.63 | 3.86 |

| Consumer role in pushing companies for sustainable packaging | Q10 | 3.55 | 4.25 |

| Companies should prioritise environmental sustainability in their packaging practices, even if it means higher costs for consumers? | Q4 | 3.23 | 3.93 |

| Willingness to pay more for eco-friendly packaging | Q11 | 2.68 | 3.62 |

| Importance of packaging that extends shelf life and reduces waste | Q15 | 3.76 | 4.43 |

| Factor 2: Environmentally Conscious Consumption Behaviour | |||

| Considering environmental footprints in purchase decisions | Q7 | 1.58 | 3.23 |

| Changed purchase due to sustainability concerns | Q9 | 1.73 | 3.03 |

| Frequency of choosing products with eco-friendly packaging | Q12 | 1.92 | 3.30 |

| Likelihood to recommend sustainable food based on packaging | Q16 | 2.28 | 3.56 |

| Importance of clear information on packaging footprint | Q8 | 2.60 | 3.94 |

| Factor 3: Environmental Literacy and Engagement | |||

| Knowledge rate of the environmental footprint of different food packaging materials | Q5 | 2.19 | 3.34 |

| Familiarity with the term ‘circular economy’ in the context of food packaging? | Q3 | 1.72 | 2.72 |

| Feeling sufficiently informed about packaging’s environmental footprint | Q17 | 1.82 | 2.73 |

| Seeking active information about sustainable practices in food packaging | Q2 | 1.76 | 3.02 |

| Engaging in environmentally friendly behaviours in daily life | Q1 | 2.77 | 3.54 |

| Factor 4: “Perceived Market Readiness” | |||

| Sufficiency of sustainable packaging options in the market | Q13 | 2.27 | 2.81 |

| Perception of current food packaging as environmentally friendly | Q6 | 2.25 | 2.42 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Consumer Perceptions of “Sustainability of Food Packaging” Questionnaire

- Demographic Information

- Gender:

- □

- Male

- □

- Female

- Age:

- □

- 15–20

- □

- 21–25

- □

- 26–28

- Occupation

- □

- Student

- □

- Working Student

- Educational Level

- □

- Undergraduate Student

- □

- Graduate Student

- □

- PhD Candidate

- Demographics

- General perception of sustainability

| Not All Important | Less Important | Moderately Important | Quit Important | Very Important | |

| 1. How often do you engage in environ mentally friendly behaviors in your daily life? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 2. Are you actively seeking information about sustainable practices in food packaging? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 3. How familiar are you with the term “circular economy” in the context of food packaging? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 4. Do you think companies should prioritize environmental sustainability in their packaging practices, even if it means higher costs for consumers? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 5. How would you rate your knowledge of the environmental footprint of different food packaging materials? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

- Perceptions and attitudes towards current food packaging practices

| Not All Important | Less Important | Moderately Important | Quit Important | Very Important | |

| 1. Do you think current food packaging practices are environmentally friendly? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 2. How often do you consider the environmental footprint of food packaging when making purchasing decisions? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 3. How important is it to you to have access to clear and accurate information about the environmental footprint of food packaging? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 4. Have you ever changed your purchase because of the sustainability of a product’s packaging? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 5. Do you think consumers should play an important role in pushing companies to adopt more sustainable packaging practices? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

- Preferences for sustainable food packaging

| Not All Important | Less Important | Moderately Important | Quit Important | Very Important | |

| 1. Would you be willing to pay a slightly higher price for food with more environmentally friendly packaging? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 2. How often do you look for active foods with eco-friendly options on the package? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 3. Do you think there are enough options for sustainable food packaging on the market? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 4. How important is it to you to have a variety of sustainable packaging options when buying food? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 5. How important is it to you to have food packaging that extends the shelf life of products and reduces food waste? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

- Barriers and incentives for Sustainable choices

| Not All Important | Less Important | Moderately Important | Quit Important | Very Important | |

| 1. How likely are you to recommend sustainable food to others based on its packaging? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 2. Do you feel sufficiently informed about the environmental footprint of different types of food packaging? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 3. How important is it to you to see clear labels indicating sustainable packaging on food? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 4. How important is it to you to feel that the companies you choose adopt transparent practices in the production and packaging of their products? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

| 5. How important is it to you that sustainable food packaging options are affordable? | ☐ 1 | ☐ 2 | ☐ 3 | ☐ 4 | ☐ 5 |

References

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer “Attitude—Behavioral Intention” Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerzyk, E. Design and Communication of Ecological Content on Sustainable Packaging in Young Consumers’ Opinions. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Birgelen, M.; Semeijn, J.; Keicher, M. Packaging and Proenvironmental Consumption Behavior: Investigating Purchase and Disposal Decisions for Beverages. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbes, C.; Beuthner, C.; Ramme, I. Consumer Attitudes towards Biobased Packaging—A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Stratakos, A.C. Application of Modified Atmosphere Packaging and Active/Smart Technologies to Red Meat and Poultry: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 1423–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti Soup: The Complex World of Food Waste Behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, R.; Burchell, K.; Riley, D. Normalising Green Behaviours: A New Approach to Sustainability Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Bugusu, B. Food Packaging—Roles, Materials, and Environmental Issues. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Li, L. Trends and Prospects in Sustainable Food Packaging Materials. Foods 2024, 13, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Mooradian, T.A. Sex, Personality, and Sustainable Consumer Behaviour: Elucidating the Gender Effect. J. Consum. Policy 2012, 35, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bussel, L.M.; Kuijsten, A.; Mars, M.; van ‘t Veer, P. Consumers’ Perceptions on Food-Related Sustainability: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Pearson, D.; James, S.W.; Lawrence, M.A.; Friel, S. Shrinking the Food-Print: A Qualitative Study into Consumer Perceptions, Experiences and Attitudes towards Healthy and Environmentally Friendly Food Behaviours. Appetite 2017, 108, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, I.; Bossink, B.A.G.; van der Sijde, P.C. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Decision to Purchase Food in Environmentally Friendly Packaging: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go from Here? Sustainability 2019, 11, 7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahma, N.; Mäkelä, J.; Niva, M.; Ganskau, E.; Minina, V. Convenience Food Consumption in the Nordic Countries and St. Petersburg Area. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P. A Systematic Review of Consumer Perceptions of Smart Packaging Technologies for Food. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piracci, G.; Casini, L.; Contini, C.; Stancu, C.M.; Lähteenmäki, L. Identifying Key Attributes in Sustainable Food Choices: An Analysis Using the Food Values Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 416, 137924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to Be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future (The Brundtland Report). Med. Confl. Surviv. 1987, 4, 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Feber, D.; Nordigården, D.; Granskog, A.; Lingqvist, O. Sustainability in Packaging: Inside the Minds of US Consumers; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Józwik-Pruska, J.; Bobowicz, P.; Hernández, C.; Szalczyńska, M. Consumer Awareness of the Eco-Labeling of Packaging. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2022, 30, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z. Meta-Analysis of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Food Products. Appetite 2021, 163, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obersteiner, G.; Cociancig, M.; Luck, S.; Mayerhofer, J. Impact of Optimized Packaging on Food Waste Prevention Potential among Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, G.; Resciniti, R.; Babin, B.J. Sustainable Packaging Design and the Consumer Perspective: A Systematic Literature Review. Ital. J. Mark. 2024, 2024, 77–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Vaccari, A.; Ferrari, E. Why Eco-Labels Can Be Effective Marketing Tools: Evidence from a Study on Italian Consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J.; Mugge, R. Judging a Product by Its Cover: Packaging Sustainability and Perceptions of Quality in Food Products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 53, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-N.; Burton, S. Enhancing Consumers’ Sustainable Consumption Practices: The Role of Alternative Sustainability Disclosures in Affecting Product Evaluations and Purchase Intentions. In Proceedings of the AMA Marketing & Public Policy Academic Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–9 June 2012; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Polonsky, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kar, A. Green Information Quality and Green Brand Evaluation: The Moderating Effects of Eco-Label Credibility and Consumer Knowledge. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2037–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Sarigöllü, E. How Brand Awareness Relates to Market Outcome, Brand Equity, and the Marketing Mix. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J. Consumer Reactions to Sustainable Packaging: The Interplay of Visual Appearance, Verbal Claim and Environmental Concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, N.; Dixit, S.; Maurya, M.; Dharwal, M. Willingness to Pay for Green Products and Factors Affecting Buyer’s Behaviour: An Empirical Study. Proc. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 49, 3595–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Long, R.; Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Wu, M.; Gan, X. Knowledge Domain and Research Progress in Green Consumption: A Phase Upgrade Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 38797–38824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J.; Young, C.W.; Hwang, K. Toward Sustainable Consumption: Researching Voluntary Simplifiers. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulos, A.; Poulis, A.; Theodoridis, P.; Kalampakas, A. Influencing Green Purchase Intention through Eco Labels and User-Generated Content. Sustainability 2023, 15, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlow, N.E.; Knott, C. Who’s Reading the Label? Millennials’ Use of Environmental Product Labels. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 1996, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ketelsen, M.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ Response to Environmentally-Friendly Food Packaging—A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pålsson, H.; Sandberg, E. Adoption Barriers for Sustainable Packaging Practices: A Comparative Study of Food Supply Chains in South Africa and Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 133811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, F.; Kurian, A. Sustainable Packaging: A Study on Consumer Perception on Sustainable Packaging Options in E-Commerce Industry. Nat. Volatiles Essent. Oils J. 2021, 8, 10547–10559. [Google Scholar]

- Heiniö, R.L.; Arvola, A.; Rusko, E.; Maaskant, A.; Kremer, S. Ready-Made Meal Packaging—A Survey of Needs and Wants among Finnish and Dutch ‘Current’ and ‘Future’ Seniors. LWT 2017, 79, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 58. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual, 3rd ed.; McGrath Hill: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, B. Cluster Analysis. Qual. Quant. 1980, 14, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression. Biometrics 1991, 47, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, E.; Vlachos, F.; Andreou, G. Approaches to Studying among Greek University Students: The Impact of Gender, Age, Academic Discipline and Handedness. Educ. Res. 2006, 48, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsiou, A.; Despotidi, C.; Kalloniatis, C.; Gritzalis, S. The Role of Users’ Demographic and Social Attributes for Accepting Biometric Systems: A Greek Case Study. Future Internet 2022, 14, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremma, O.; Kontogeorgos, A.; Karipidis, P.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Mapping the Market Segments for the Consumers of Greek Cooperative Food Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Attitudes of European Towards Waste Management and Resource Efficiency; Report Flash Eurobarometer Survey; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green Products: An Exploratory Study on the Consumer Behaviour in Emerging Economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustagi, P.; Prakash, A. Review on Consumer’s Attitude & Purchase Behavioral Intention towards Green Food Products. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 9257–9273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green consumption: Behavior and norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A. “Greening” the Marketing Mix: Do Firms Do It and Does It Pay Off? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.d.L. Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A Systematic Review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B. Understanding the Influence of Eco-Label, and Green Advertising on Green Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Green Brand Equity. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2022, 28, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An Analysis of Definitions, Strategy Steps, and Tools through a Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The Sustainability Liability: Potential Negative Effects of Ethicality on Product Preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, M. Enhancing Green Purchase Intentions: The Effects of Product Transformation Salience and Consumer Traceability Knowledge. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Catană, Ș.-A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.I.; Ioanid, A. Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior toward Green Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confetto, M.G.; Covucci, C.; Addeo, F.; Normando, M. Sustainability Advocacy Antecedents: How Social Media Content Influences Sustainable Behaviours among Generation Z. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 758–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question Code | Question | Mean Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | ||

| Q19 | Trust in companies adopting transparent sustainable practices | 3.036 | 4.167 |

| Q7 | Considering of environmental footprint in purchase decisions | 1.580 | 3.232 |

| Q5 | Knowledge rate of the environmental footprint of different food packaging materials | 2.189 | 3.338 |

| Q13 | Sufficiency of sustainable packaging options in the market | 2.272 | 2.808 |

| Code | Variable (Question) | Coefficient B (β) | S.E. | Wald Statistic | Wald Sig. | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q18 | Importance of clear sustainability labels on packaging | 0.423 | 0.222 | 1.908 | 0.056 ** | 1.527 |

| Q17 | Feeling sufficiently informed about packaging’s environmental footprint | 0.659 | 0.191 | 3.317 | <0.001 *** | 1.932 |

| Q12 | Frequency of choosing products with eco-friendly packaging | 0.383 | 0.229 | 1.670 | 0.095 * | 1.467 |

| Q8 | Importance of clear information on packaging footprint | 0.660 | 0.199 | 3.3175 | <0.001 *** | 1.936 |

| Q6 | Perception of current food packaging as environmentally friendly | 0.672 | 0.211 | 3.1919 | 0.001 *** | 1.960 |

| Q2 | Seeking active information about sustainable practices in food packaging | 0.497 | 0.212 | 2.342 | 0.019 ** | 1.645 |

| n/a | Intercept | −11.24503 | 1.526 | −7.3675 | <0.001 *** | 1.31 × 10−5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbarousis, G.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Kontogeorgos, A.; Skalkos, D. “Innovatives” or “Sceptics”: Views on Sustainable Food Packaging in the New Global Context by Generation Z Members of an Academic Community. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157116

Barbarousis G, Chatzitheodoridis F, Kontogeorgos A, Skalkos D. “Innovatives” or “Sceptics”: Views on Sustainable Food Packaging in the New Global Context by Generation Z Members of an Academic Community. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):7116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157116

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbarousis, Gerasimos, Fotios Chatzitheodoridis, Achilleas Kontogeorgos, and Dimitris Skalkos. 2025. "“Innovatives” or “Sceptics”: Views on Sustainable Food Packaging in the New Global Context by Generation Z Members of an Academic Community" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 7116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157116

APA StyleBarbarousis, G., Chatzitheodoridis, F., Kontogeorgos, A., & Skalkos, D. (2025). “Innovatives” or “Sceptics”: Views on Sustainable Food Packaging in the New Global Context by Generation Z Members of an Academic Community. Sustainability, 17(15), 7116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157116