Exploring Service Needs and Development Strategies for the Healthcare Tourism Industry Through the APA-NRM Technique

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Critical Driving Factors for the Evaluation System of Healthcare Tourism

2.1.1. Medical Services (MSs)

2.1.2. Medical Facilities (MFs)

2.1.3. Tour Planning (TP)

2.1.4. Hospitality Facilities (HFs)

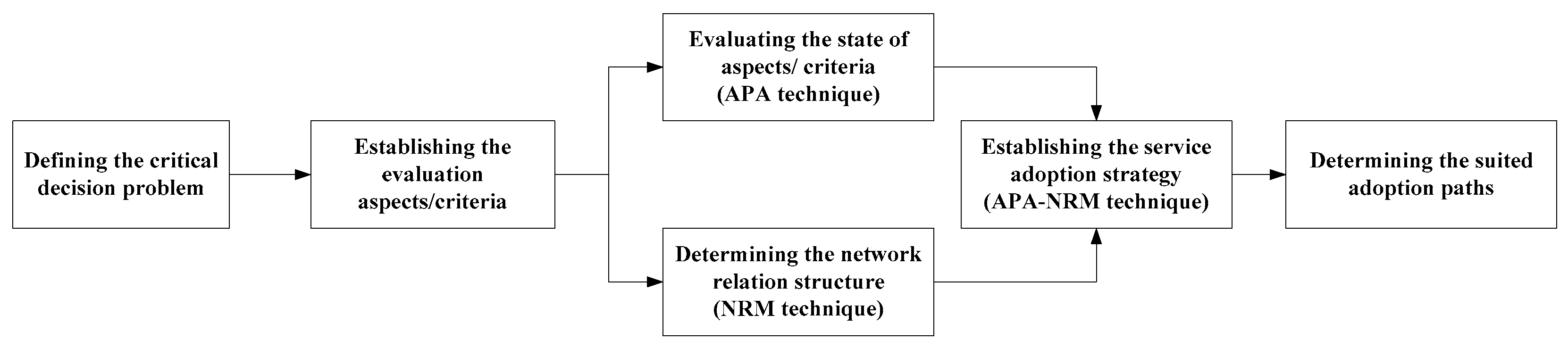

3. The Service System for Healthcare Tourism Using the APA-NRM Technique

3.1. The Population Sample Information, Explanation, and Reliability Analysis

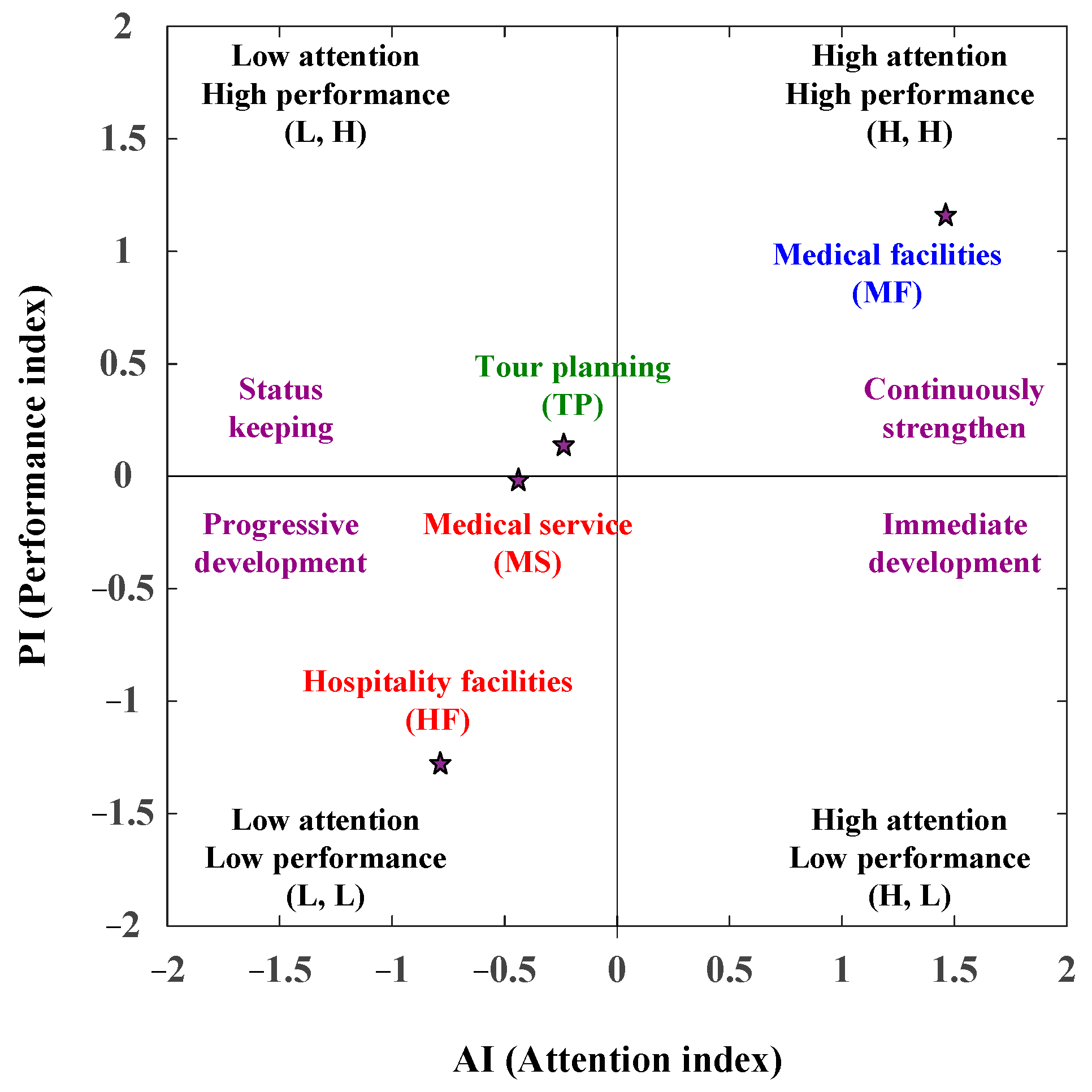

3.2. The APA (Attention and Performance Analysis) Analysis

3.3. The NRM Analysis Based on the DEMATEL Technique

- (1)

- Analyze the original average matrix

- (2)

- Evaluate the direct influence matrix

- (3)

- Evaluate the indirect influence matrix

- (4)

- Determine the full influence matrix

- (5)

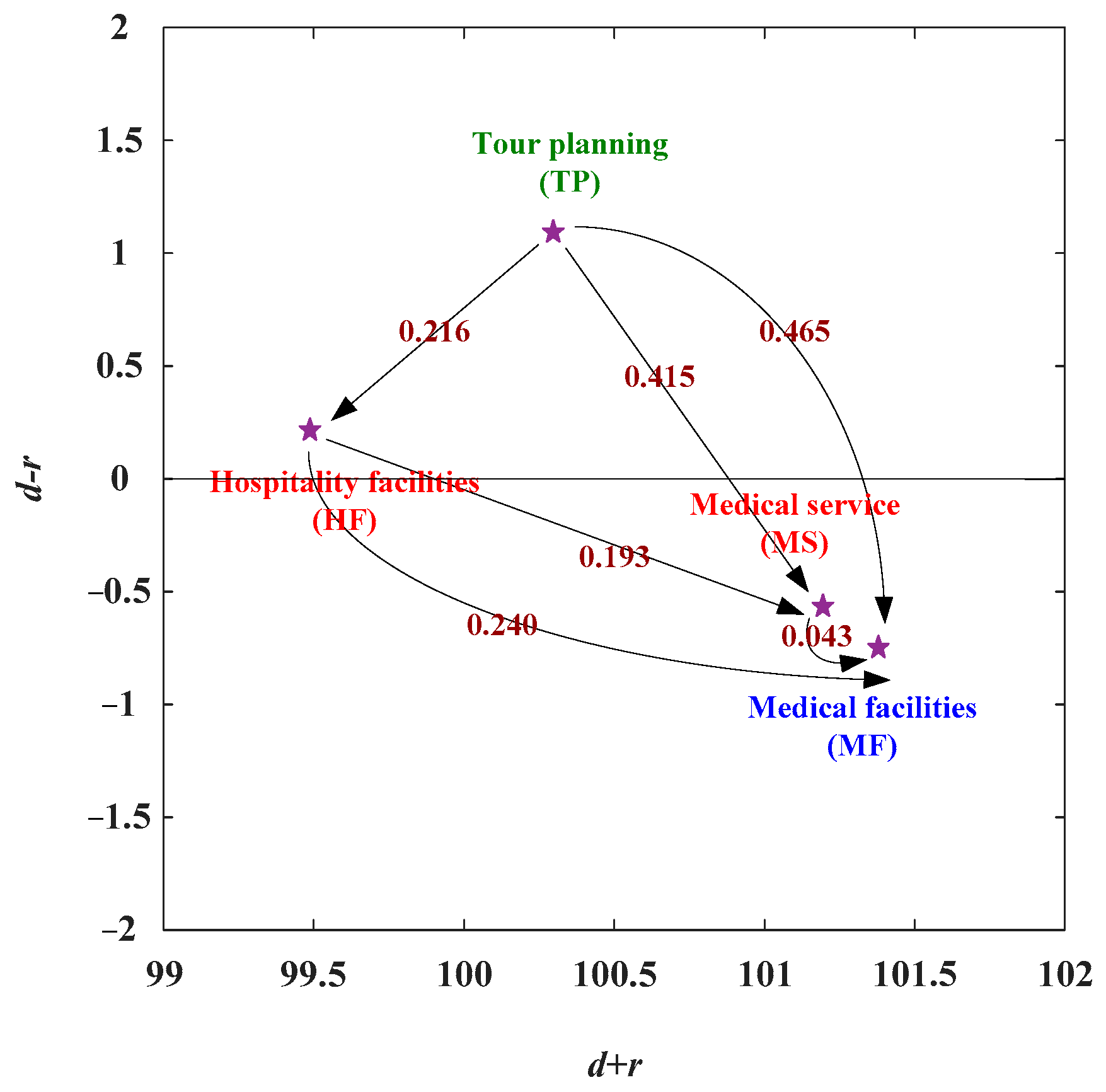

- Determine the NRM (network relation map)

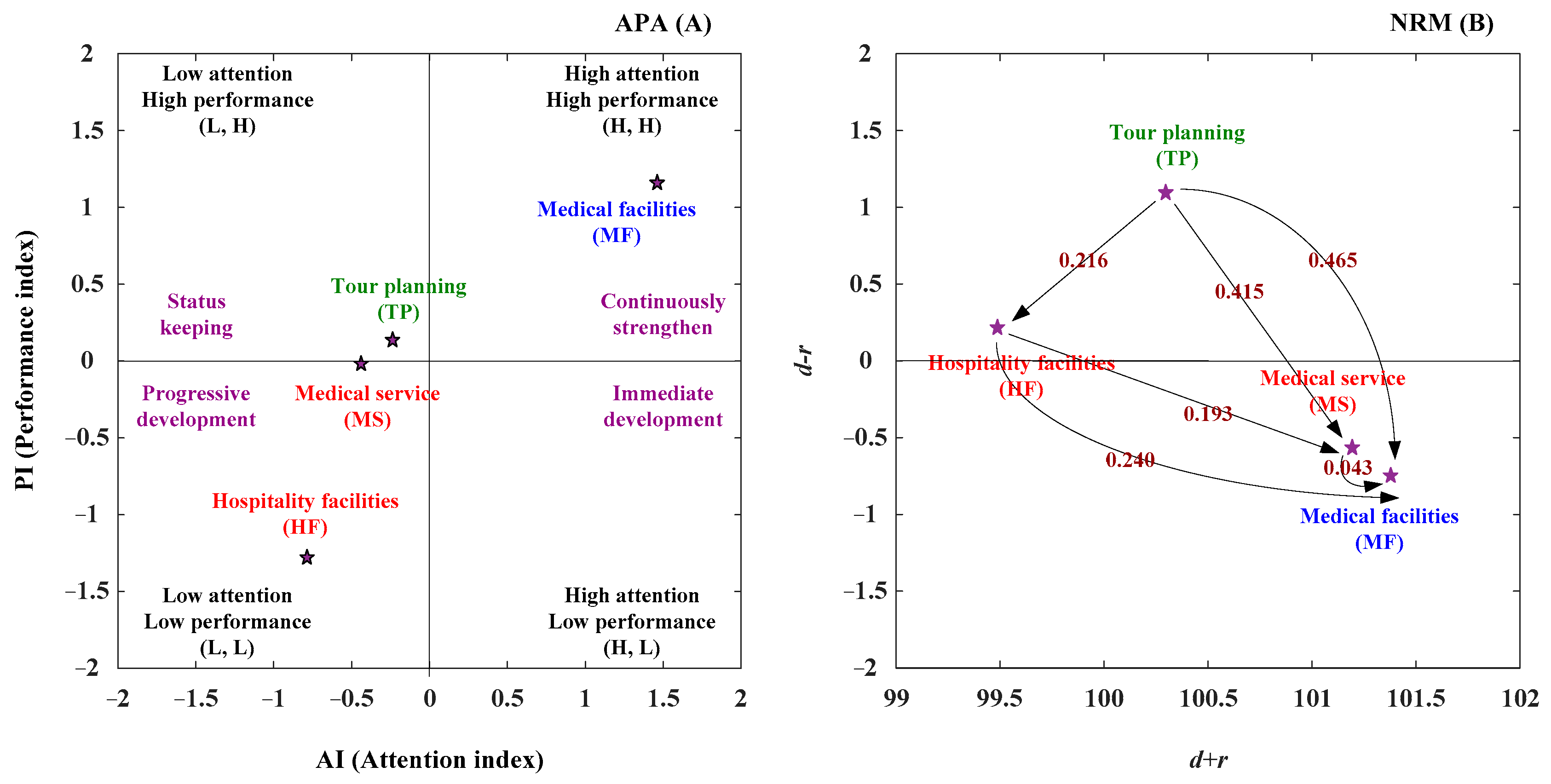

3.4. The APA-NRM Analysis

3.5. Establish the Suitable Adoption Paths by AI and PI Ranking

4. The APA-NRM Analysis for the Healthcare Tourism

4.1. Determine the Adoption Strategy and Suitable Adoption Paths

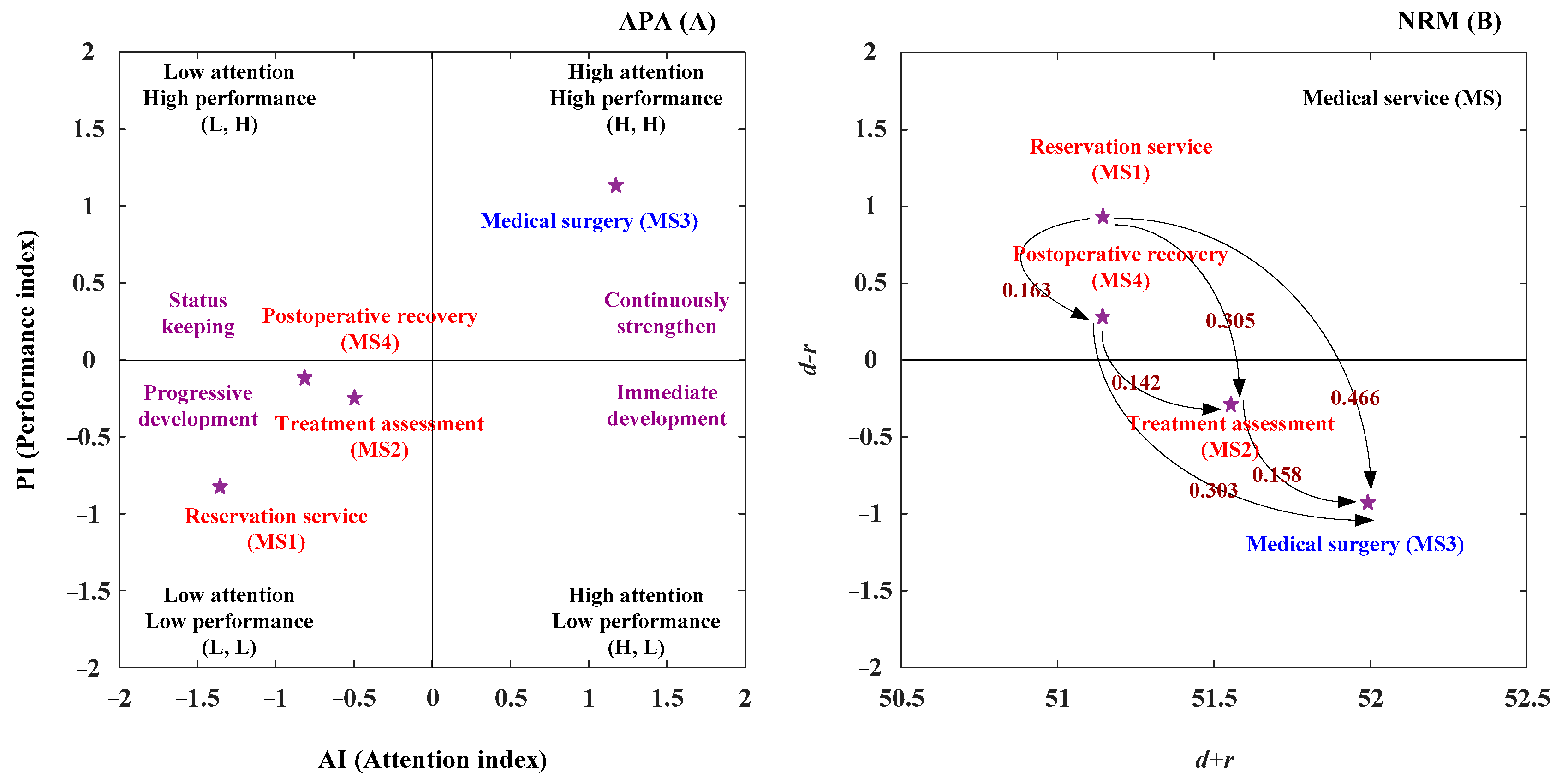

4.1.1. The Aspect of MSs (Medical Services)

4.1.2. The Aspect of MF (Medical Facilities)

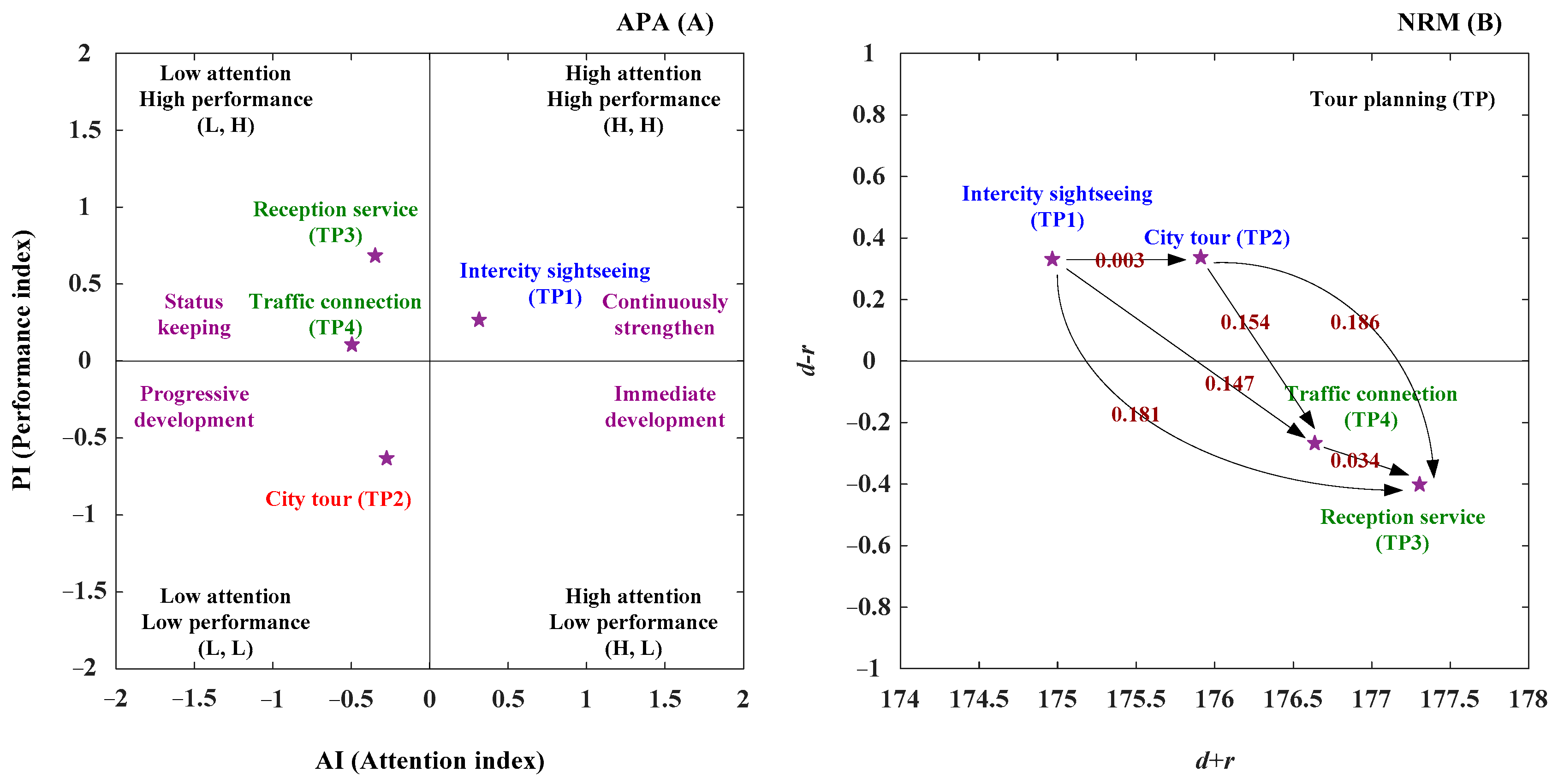

4.1.3. The Aspect of TP (Tour Planning)

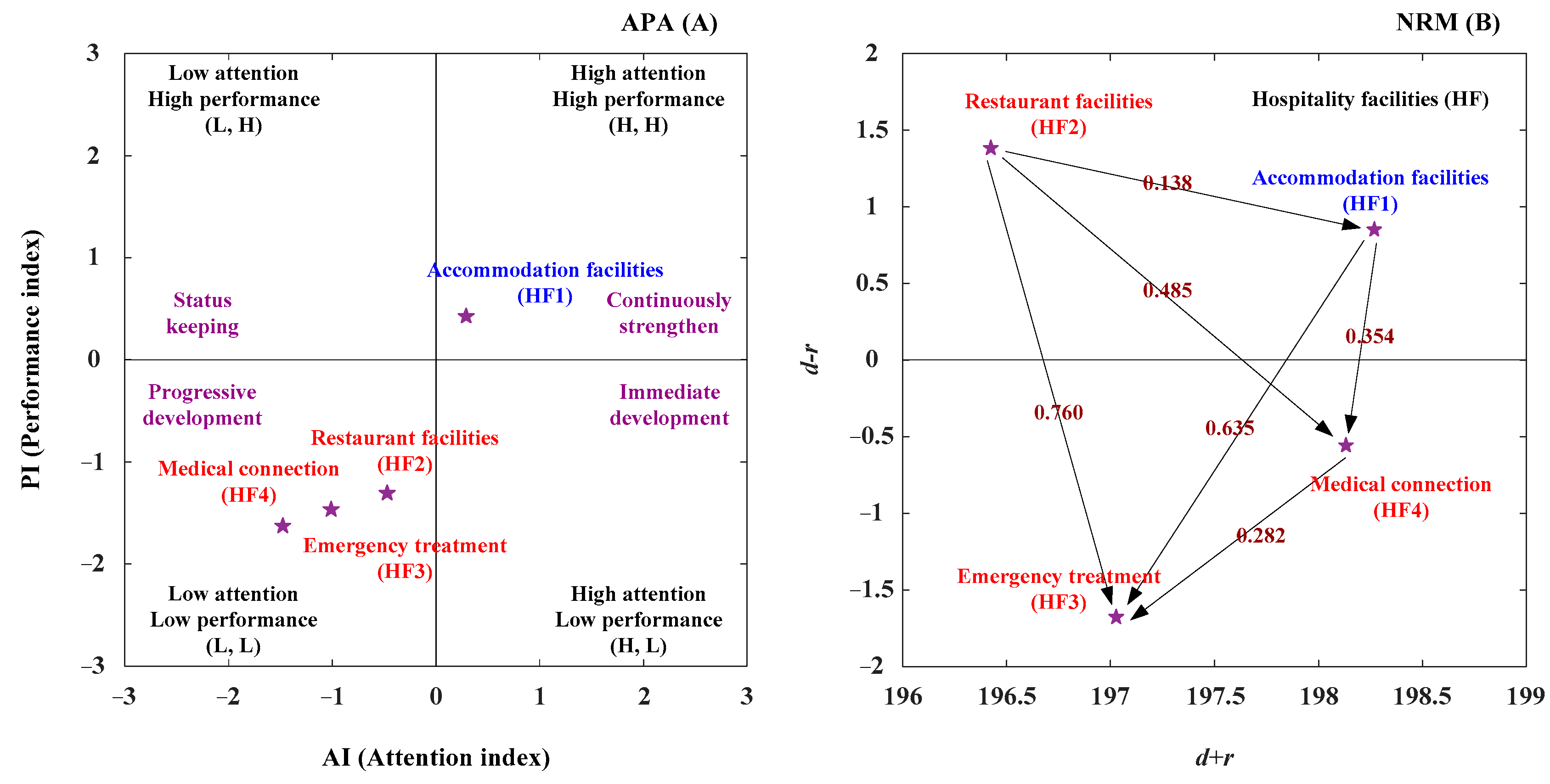

4.1.4. The Aspect of HT (Hospitality Facilities)

4.2. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- In the APA analysis, travelers/patients pay more attention to MFs (medical facilities) than MSs (medical services), and MFs (medical facilities) have a higher performance than MSs (medical services), which also means that travelers and patients pay attention and choose a comprehensive and excellent healthcare tourism itinerary with nice medical facilities/services. Furthermore, travelers/patients pay more attention to TP (tour planning) than HFs (hospitality facilities), and TP (tour planning) performs better. This result means that travelers and patients will pay attention to and choose medical sightseeing tours (city tours or international tours) with comprehensive transportation services and friendly guide receptions. In the MFs (medical facilities), travelers/patients pay more attention to the criteria of surgical equipment (MF1), diagnosis facilities (MF2), medical equipment (MF3), and medical examination facilities (MF4). However, the performance of the MF4 criterion was less than the average level. Furthermore, MF4 (medical examination facilities) is the dominant criterion in the NRM (network relation map) analysis, while MF2 (diagnostic facilities) is the subordinate aspect. Therefore, service providers must consider the needs of travelers and patients and cooperate further with medical hospitals that have complete medical examination facilities. By collaborating with health screening and early treatment centers, service providers can provide early warning and treatment for travelers and patients with medical tests and examination equipment.

- (2)

- In the NRM analysis, TP (tour planning) is the dominant aspect of healthcare tourism evaluation systems, while MFs (medical facilities) is the subordinate aspect. The TP (tour planning) aspect can enhance the HFs aspect. Then, the HFs aspect can improve the MSs (medical services) aspect, and the MSs (medical services) aspect can enhance the MFs (medical facilities) aspect. Therefore, we need to improve the overall satisfaction with healthcare tourism services. It is advisable to start with TP (tour planning), then improve HFs (hospitality facilities), and finally strengthen MSs (medical services) and MFs (medical facilities). In other words, most customers’ primary healthcare tourism needs are travel. After relieving stress and relaxing, they can gain a deeper understanding of their current physical condition through a comprehensive full-body check-up and ultimately carry out early prevention and treatment of diseases. Therefore, increasing travelers’ and patients’ interest through itinerary planning will be attractive, which is also why they become healthcare tourism customers. Additionally, healthcare tourism service providers must consider the accommodation and dining needs of different travelers and patients during their trips and customize the arrangements accordingly, such as the accommodation regulations for the elderly and the design and auxiliary facilities required for them. However, some healthcare tourism service providers can offer meal arrangements for travelers/patients before special medical examinations; these special services can reduce the inconvenience of travelers/patients during their trip. In addition, for medical services (MSs) and medical facilities (MFs), although travelers/patients attach more importance to medical facilities (MFs), without good medical services, it is difficult for travelers/patients to trust that service providers are truly addressing the needs of travelers/patients and arranging best suitable medical services and treatments for them.

- (3)

- In the TP (tour planning), travelers/patients pay more attention to the TP1 (intercity sightseeing) criterion than the TP2 (city tour), TP3 (reception service), and TP4 (traffic connection) criteria. However, the performance of the TP2 (city tour) criterion was less than the average for the performance indicator. Furthermore, the TP1 (intercity sightseeing) criterion is the dominant criterion in the NRM (network relation map) analysis, while TP3 (reception service) is the subordinate aspect. Therefore, healthcare tourism service providers should start by considering travel arrangements. Planning the trip and travel arrangements includes arranging health check-ups, routes, and options for medical treatment for tourists and patients, because high-end health checks and medical treatment hospitals are more suitable for them. However, most high-end health checks and medical treatment hospitals are concentrated in cities and urban areas. At the same time, those with a particular geographical landscape and unique historical and cultural characteristics are mainly located in the surrounding towns and far from the cities. Consequently, integrating tourist and city tours in the city has become a service provider’s challenge. Intercity sightseeing can increase the diversity of the itinerary, while fixed-point tourism can increase the depth of the itinerary and integrate it into local life. Therefore, according to the flexibility of travel time and budgetary arrangements of travelers and patients, it is recommended to provide a variety of itineraries. Those with more time can arrange long-term leisure and wellness trips to a specific place. They can arrange in-depth travel routes to each city for one or more weeks. For those still working, you can arrange a health check-up plan based on the length of your vacation in the city. They can also plan a route to the counties and towns near the city. This can meet the needs of itinerary diversification while reducing travel time. Excessive traveling will increase the burden and fatigue of travelers and patients. It is recommended that passengers and patients travel in specific cars to improve transportation convenience and reduce fatigue. In contrast, we can reduce the inconveniences of travelers/patients using public transit by healthcare tourism service providers with more flexible schedules to reduce the fatigue of passengers/patients.

- (4)

- Healthcare tourism provides a significant opportunity to enhance the quality of life for middle-aged and elderly people. Combining professional medical care with meaningful travel experiences offers comprehensive solutions for the health and well-being of people in their later years. This study establishes a healthcare tourism evaluation system to explore the interrelationships between various dimensions and further identifies the most suitable adoption paths. Three suitable adoption paths (TP → MS → MF; TP → HF → MF; TP → HF → MS → MF) have been identified for the evaluation system of healthcare tourism. The TP (tour planning) aspect influences the MSs (medical services) aspect, and the MSs aspect enhances the MFs (medical facilities) aspect in the second suitable adoption path. The TP aspect enhances the HFs (hospitality facilities) aspect, and the HFs aspect strengthens the MFs (medical facilities) aspect in the third suitable adoption path. The TP (tour planning) aspect influences the HFs aspect, the HFs aspect affects the MSs aspect, and the MSs aspect affects the MFs aspect in the fourth-suitable adoption path. From these three most suitable adoption paths, it is evident that the TP (tour planning) aspect is the primary dominant aspect, while the MFs (medical facilities) aspect is the central subordinate aspect among the three main travel companion categories (traveling with family/friends, company colleagues, and alone).

- (5)

- For traveling with family/friends groups, this group typically combines family tourism formats, resulting in the most diverse member composition and requiring consideration of various needs. The advantage is that some members serve as primary caregivers and companions, enabling mutual support. The main purpose is family companionship and reunion, allowing for more relaxed and flexible itinerary planning. Some less structured, in-depth travel at specific locations can increase members’ interaction opportunities. For the traveling with a company colleagues group, this category includes corporate employee trips and incentive travel, and features a more homogeneous group composed primarily of company colleagues and work partners. While some may participate with spouses or companions, most are company members and their families. Short-term itineraries are suitable, and since the age gap is typically smaller than in family travel, more intensive intercity travel can be arranged. Health examinations and tests should be completed early in the journey, allowing members to receive their health examination results afterward. Traveling alone, these groups face more flexibility but are more complex and require health status evaluation. For those in good health and physical condition, companion travel similar to the company colleagues group can be arranged, reducing risks through mutual support during the journey. For elderly or less healthy individuals, location-specific travel with care resources is preferred. Institutional fixed-point travel destinations can arrange experiential exchange activities and typically maintain long-term partnerships with nearby medical institutions to provide emergency response capabilities.

- (6)

- The current research found three main categories of travel companions for healthcare tourism based on the composition of travel companions (traveling with family/friends groups, traveling with corporate colleagues groups, and traveling alone groups). This study can help to understand the main driving factors for healthcare tourism and the relationship between the driving factors. However, this study considered that subsequent researchers should still explore the healthcare tourism evaluation system based on the different groups. In addition, this study also found that, from the sample statistical analysis, the female sample is the leading group of customers, which is higher than that of the male group. In addition to the fact that women generally live longer than men, they are also more enthusiastic about group travel or group activities. Consequently, health tourism service providers should pay more attention to women’s health tourism demand, understand their preferred travel preferences and related medical needs, and provide diversified travel itinerary design and health examination and testing programs. In addition, analysis of sample age composition shows that traditional market segmentation based on legal retirement age cannot fully meet market demands. When we consider healthcare tourism as a progressive development stage, for the middle-aged group (over 40 years), medical tourists have better physical strength and health condition, but relatively less vacation time and funds available; their wellness tourism focuses primarily on stress relief and health status assessment. Launching wellness tourism packages that mainly include health examinations and screening, along with short-term urban tourism, is recommended. On the other hand, people aged 60 and over, who generally enter the retirement phase or transfer family businesses to the next generation, gradually have enough capital to enjoy retirement because of their financial accumulation. However, their physical condition and strength may not be as strong as that of the middle-aged group. They can, therefore, consider long-term fixed-point deep tourism as the primary focus, together with short-distance in-depth visits to nearby cities and villages.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tham, A. Sand, surgery and stakeholders: A multi-stakeholder involvement model of domestic medical tourism for Australia’s Sunshine Coast. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Esfahani, S.; Ridderstaat, J.; Ozturk, A.B. Health tourism in a developed country with a dominant tourism market: The case of the United States’ travellers to Canada. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Hyun, S.S. The Future of Medical Tourism for Individuals’ Health and Well-Being: A Case Study of the Relationship Improvement between the UAE (United Arab Emirates) and South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ghasemi, M.; Ghadiri Nejad, M.; Khandan, A.S. Assessing the Potential Growth of Iran’s Hospitals with Regard to the Sustainable Management of Medical Tourism. Health Soc. Care Community 2023, 2023, 8734482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekouropoulos, G.; Vasileiou, A.; Hoxha, G.; Dimitriadis, A.; Zervas, I. Sustainable Approaches to Medical Tourism: Strategies for Central Macedonia/Greece. Sustainability 2024, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.C.; Wang, Y.L.; Pai, L.N.; Yang, S.H.; Chang, T.Y.; Chen, S.H.; Jaing, T.H. Word-of-mouth referrals between patients are a critical component of medical tourism for pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation. Medicine 2025, 104, e41244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsartsara, S.I. Definition of a new type of tourism niche-The geriatric tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Chen, H.W.; Li, H.Y.; Hsu, H.H.; Chen, L.C.; Tang, W.R. Experiences of oncology healthcare personnel in international medical service quality: A phenomenological study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, K.H.; Kim, S.M. Application of Fairness Theory to Medical Tourists’ Dissatisfaction and Complaint Behaviors: The Moderating Role of Patient Participation in Medical Tourism. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2018, 44, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Samad, S.; Manaf, A.A.; Ahmadi, H.; Rashid, T.A.; Munshi, A.; Almukadi, W.; Ibrahim, O.; Hassan Ahmed, O. Factors influencing medical tourism adoption in Malaysia: A DEMATEL-Fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewicz-Kreft, M.; Kuczamer-Kłopotowska, S.; Kozłowski, A. The role and importance of perceived risk in medical tourism. Applying the theory of planned behaviour. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikkel, Y.Y.; Eliad, H.; Ofir, H.; Zeidan, M.; Eldor, L.; Nakhleh, H.; Ramon, Y.; Zeltzer, A.A. Mending a World of Problems: 12-Year Review of Medical Tourism Inbound Complications in a Tertiary Centre. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025, 49, 2492–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S.; Ormond, M.; Musa, G.; Mohamed Isa, C.R.; Thirumoorthi, T.; Bin Mustapha, M.Z.; Kanapathy, K.A.P.; Chiremel Chandy, J.J. Connecting with prospective medical tourists online: A cross-sectional analysis of private hospital websites promoting medical tourism in India, Malaysia and Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, D.; Batouei, A.; Iranmanesh, M.; Kim, K.; Hyun, S.S. Hospital prestige in medical tourism: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.; Brochado, A.; Troilo, M. Listening to the murmur of water: Essential satisfaction and dissatisfaction attributes of thermal and mineral spas. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Munshi, A.; Rastogi, K.; Ganesh, T.; Bansal, K.; Manikandan, A.; Mohanti, B.K.; Tyagi, B.; Vaishya, S.; Ghosh, B.; et al. Cancer care medical tourism in the national capital region of India—Challenges for overseas patients treated in two private hospitals. Health Policy Technol. 2022, 11, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.F.; Vongvisitsin, T.B.; Li, P.; Pan, Y.; Ryan, C. Revisiting medical tourism research: Critical reviews and implications for destination management and marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberts, C.E.; LaFree, A. Complications from bariatric medical tourism: Lessons for the emergency physician from selected case reports. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2025, 90, 252.e251–252.e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, B.; Lovelock, K. “We had a ball … as long as you kept taking your painkillers” just how much tourism is there in medical tourism? Experiences of the patient tourist. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, R.; Cavallone, M.; Ciasullo, M.V.; Palumbo, R. Beyond the rhetoric of health tourism: Shedding light on the reality of health tourism in Italy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam-Jo, S.K.; Kim, K.B.; Oh, C. Beaches for Everyone? Marine Tourism for Mobility Impaired Visitors in Busan, Korea. J. Coast. Res. 2021, 114, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaee, M.H.; Al-e-Hashem, S. Stochastic medical tourism problem with variable residence time considering gravity function. Rairo-Oper. Res. 2022, 56, 1685–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guru, S.; Sinha, A.; Kautish, P. Determinants of medical tourism: Application of Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchical Process. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 4819–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Chan, C.S. Opportunities, challenges and implications of medical tourism development in Hong Kong. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetscherin, M.; Stephano, R.M. The medical tourism index: Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Medhekar, A.; Wong, H.Y.; Cobanoglu, C. Factors influencing outbound medical travel from the USA. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.S.; Nguyen, T.M.T.; Wang, C.N.; Day, J.D.; Dang, T.M.H. Grey System Theory in the Study of Medical Tourism Industry and Its Economic Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannake, G.; Economou, A.; Metaxas, T.; Geitona, M. Medical Tourism in the Region of Thessaly, Greece: Opinions and Perspectives from Healthcare Providers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charati, M.K.; Gholian-Jouybari, F.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Paydar, M.M.; Sadeghi, F. Designing a sustainable dental tourism supply chain considering waste treatment. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 342, 173–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, S.; Shimizu, Y. Designing methods of human interface for supervisory control systems. Control Eng. Pract. 1999, 7, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed-Hosseini, S.M.; Safaei, N.; Asgharpour, M.J. Reprioritization of failures in a system failure mode and effects analysis by decision making trial and evaluation laboratory technique. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2006, 91, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Tzeng, G.H. A value-created system of science (technology) park by using DEMATEL. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 9683–9697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.W.; Tzeng, G.H. Identification of a threshold value for the DEMATEL method using the maximum mean de-entropy algorithm to find critical services provided by a semiconductor intellectual property mall. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 9891–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Hsieh, M.S.; Tzeng, G.H. Evaluating vehicle telematics system by using a novel MCDM techniques with dependence and feedback. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 6723–6736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Wang, F.K.; Tzeng, G.H. The best vendor selection for conducting the recycled material based on a hybrid MCDM model combining DANP with VIKOR. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 66, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Tzeng, G.H.; Yeih, W.C.; Wang, Y.J.; Yang, S.C. Revised DEMATEL: Resolving the Infeasibility of DEMATEL. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 6746–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L. A novel hybrid decision-making model for determining product position under consideration of dependence and feedback. Appl. Math. Model. 2015, 39, 2194–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Khalili-Damghani, K.; Rahmatian, R. A hybrid fuzzy MCDM method for measuring the performance of publicly held pharmaceutical companies. Ann. Oper. Res. 2015, 226, 589–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Shih, Y.H.; Tzeng, G.H.; Yu, H.C. A service selection model for digital music service platforms using a hybrid MCDM approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 48, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.W.V.; Chang, K.; Yin, M.S.; Sheu, R.S. Critical factors for implementing a programme for international MICE professionals: A hybrid MCDM model combining DEMATEL and ANP. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1527–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Lim, M.K.; Wu, K.J. Corporate sustainability performance improvement using an interrelationship hierarchical model approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Kuo, C.L. A service position model of package tour services based on the hybrid MCDM approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2478–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.H.; Tzeng, G.H. Exploring heritage tourism performance improvement for making sustainable development strategies using the hybrid-modified MADM model. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 921–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L. Establishing environment sustentation strategies for urban and rural/town tourism based on a hybrid MCDM approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2360–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Kuo, C.L. Establishing Competency Development Evaluation Systems and Talent Cultivation Strategies for the Service Industry Using the Hybrid MCDM Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragones-Beltran, P.; Gonzalez-Cruz, M.C.; Leon-Camargo, A.; Vinoles-Cebolla, R. Assessment of regional development needs according to criteria based on the Sustainable Development Goals in the Meta Region (Colombia). Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1101–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.J.; Huang, C.G.; Nedjati, A.; Yazdi, M. Discovering the sustainable challenges of biomass energy: A case study of Tehran metropolitan. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 3957–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L. Enhancing competency development and sustainable talent cultivation strategies for the service industry based on the IAA-NRM approach. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 5071–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhu, N.; Zheng, S.; Zou, L.; Wang, X. Analyzing critical success factors for green supplier selection: A combined DEMATEL-ISM approach and convolutional neural network based consensus model. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 171, 112760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österle, A.; Diesenreiter, C.; Glinsner, B.; Reichel, E. Inbound and outbound medical travel in Austria. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2021, 35, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Islam, M.A.; Islam, M.K.; Begum, A.; Poly, N.A.; Cheng, F.; Xu, J.F. Determinants of Bangladeshi patients’ decision-making process and satisfaction toward medical tourism in India. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1137929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Chatterjee, K.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Kar, S. Evaluation and selection of medical tourism sites: A rough analytic hierarchy process based multi-attributive border approximation area comparison approach. Expert Syst. 2018, 35, e12232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Ryan, C. Chinese seniors holidaying, elderly care, rural tourism and rural poverty alleviation programmes. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.L.; Seo, B.R. Developmental Strategies of the Promotion Policies in Medical Tourism Industry in South Korea: A 10-Year Study (2009–2018). Iran. J. Public Health 2019, 48, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medhekar, A.; Wong, H.Y.; Hall, J.E. Health-care providers perspective on value in medical travel to India. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.C.; Chou, P.C.; Yeh, R.K.J.; Tseng, H.T. Factors influencing Chinese tourists’ intentions to use the Taiwan Medical Travel App. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suess, C.; Kang, S.; Dogru, T.; Mody, M. Understanding the influence of “feeling at home” on healthcare travelers’ well-being: A comparison of Airbnb and hotel homescapes. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspects/Criteria | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | |

| Reservation service (MS1) | The doctor and nurse will assist patients with confirming surgical procedures, appointments, personal payment, insurance applications, and other appointment scheduling services. |

| Treatment assessment (MS2) | Doctors, nurses, and medical technicians will assist patients in arranging physical examinations and diagnostic tests, provide medical advice, and obtain informed consent at the end of the process. |

| Medical surgery (MS3) | Doctors and nurses will confirm the patient’s condition and assist in arranging cross-disciplinary surgery, anesthesia processes, specialized surgeries, and coordinating support services. |

| Postoperative recovery (MS4) | After the patient has completed the surgery, the nurse will assist the patient in arranging cross-disciplinary medical treatment, specialized medical treatment, postoperative outpatient, and home medical services. |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | |

| Surgical equipment (MF1) | The facility will provide a safe and comfortable sterile surgical environment for patients to avoid infections during surgery and thereby increase the chances of patient recovery. |

| Diagnosis facility (MF2) | The facility will provide customized medical and nursing services that respect patient privacy, allowing postoperative patients to recover and return home with adequate medical care. |

| Medical equipment (MF3) | The facility will provide emergency medical rescue facilities and related advanced medical and surgical equipment to reduce the burden on the patient’s body and improve the recovery rate. |

| Medical examination facilities (MF4) | The facility will provide travelers/patients with a complete full-body health check-up and arrange for relevant blood tests and organ function examinations before the patient’s surgery. |

| Tour planning (TP) | |

| Intercity sightseeing (TP1) | Tour guides and leaders will assist clients, their friends, and their families in arranging long-distance travel that spans more than a day, crosses two counties, and includes accommodation and tours. |

| City tour (TP2) | Tour guides and leaders will help clients and their friends and family arrange city sightseeing, attraction visits, and short-term travel services that do not require accommodation. |

| Reception service (TP3) | Tour guides and leaders will assist clients and their friends and family in arranging airport pick-up services, accommodation arrangements, and guidance on subsequent itinerary arrangements and introductions. |

| Traffic connection (TP4) | Travel agency bus drivers and outsourced shuttle service personnel assist clients, friends, and family with shuttle services between accommodation and tour attractions. |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | |

| Accommodation facilities (HF1) | During the journey, patients/travelers are provided with a home-like environment to relieve fatigue and get sufficient rest. |

| Restaurant facilities (HF2) | During the journey, patients/travelers can taste local cuisine, replenishing their energy and allowing them to enjoy regional delicacies. |

| Emergency treatment (HF3) | During the journey, adequate medical emergency measures are provided for patients/travelers, therefore reducing their worries. |

| Medical connection (HF4) | During the journey, an emergency medical network is established with the local medical system at all times to provide emergency medical shuttle services when necessary. |

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 45 | 36.29% |

| Female | 79 | 63.71% | |

| Age | Less than 39 years | 32 | 25.81% |

| 40 to 49 years | 47 | 37.90% | |

| 50 to 59 years | 32 | 25.81% | |

| Over 60 years | 13 | 10.48% | |

| Main travel companions | Traveling alone | 17 | 13.71% |

| Traveling with family/friends | 94 | 75.81% | |

| Traveling with company colleagues | 13 | 10.48% | |

| Total | 124 | 100% |

| Items | Aspects/Criteria | Alpha | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention indicator | 0.982 | High | |

| Performance indicator | 0.986 | High | |

| Aspects of evaluation system | 0.977 | High | |

| Criteria of aspects | Medical services (MSs) | 0.974 | High |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 0.984 | High | |

| Tour planning (TP) | 0.967 | High | |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 0.972 | High | |

| AI | PI | (AD, PD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | SS | MI | SI | ||

| Medical services (MSs) | 6.597 | −0.439 | 6.881 | −0.018 | L, L |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 7.127 | 1.461 | 7.111 | 1.160 | H, H |

| Tour planning (TP) | 6.653 | −0.237 | 6.911 | 0.137 | L, H |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 6.500 | −0.786 | 6.635 | −1.279 | L, L |

| Average | 7.127 | 1.461 | 7.111 | 1.160 | |

| Standard deviation | 6.500 | −0.786 | 6.635 | −1.279 | |

| Maximum | 6.719 | 0.000 | 6.885 | 0.000 | |

| Minimum | 0.279 | 1.000 | 0.195 | 1.000 | |

| Aspects | MS | MF | TP | HF | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | 0.000 | 3.202 | 2.847 | 2.847 | 8.895 |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 3.226 | 0.000 | 2.847 | 2.823 | 8.895 |

| Tour planning (TP) | 2.919 | 2.992 | 0.000 | 3.073 | 8.984 |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 2.871 | 2.871 | 3.040 | 0.000 | 8.782 |

| Total | 9.016 | 9.065 | 8.734 | 8.742 | - |

| Aspects | MS | MF | TP | HF | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | 0.000 | 0.353 | 0.314 | 0.314 | 0.981 |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 0.356 | 0.000 | 0.314 | 0.311 | 0.981 |

| Tour planning (TP) | 0.322 | 0.330 | 0.000 | 0.339 | 0.991 |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 0.317 | 0.317 | 0.335 | 0.000 | 0.969 |

| Total | 0.995 | 1.000 | 0.964 | 0.964 | - |

| Aspects | Sum of Row | Sum of Column | Sum of Row and Column | Importance of Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | 0.981 | 0.995 | 1.976 | 2 |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 0.981 | 1.000 | 1.981 | 1 |

| Tour planning (TP) | 0.991 | 0.964 | 1.955 | 3 |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 0.969 | 0.964 | 1.933 | 4 |

| Aspects | MS | MF | TP | HF | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | 12.538 | 12.491 | 12.148 | 12.156 | 49.334 |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 12.445 | 12.584 | 12.148 | 12.158 | 49.335 |

| Tour planning (TP) | 12.555 | 12.597 | 12.316 | 12.238 | 49.705 |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 12.346 | 12.391 | 12.027 | 12.119 | 48.883 |

| Total | 49.884 | 50.063 | 48.638 | 48.671 | - |

| Aspects | MS | MF | TP | HF | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | 12.538 | 12.844 | 12.462 | 12.470 | 50.315 |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 12.801 | 12.584 | 12.462 | 12.469 | 50.316 |

| Tour planning (TP) | 12.877 | 12.927 | 12.316 | 12.577 | 50.696 |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 12.663 | 12.708 | 12.362 | 12.119 | 49.852 |

| r | 50.879 | 51.063 | 49.601 | 49.635 | - |

| Aspects | {d} | {r} | {d + r} | {d − r} |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | 50.315 | 50.879 | 101.194 | −0.565 |

| Medical facilities (MFs) | 50.316 | 51.063 | 101.379 | −0.747 |

| Tour planning (TP) | 50.696 | 49.601 | 100.297 | 1.095 |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 49.852 | 49.635 | 99.487 | 0.217 |

| Aspects | MS | MF | TP | HF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical services (MSs) | - | |||

| Medical facilities (MFs) | −0.043 | - | ||

| Tour planning (TP) | 0.415 | 0.465 | - | |

| Hospitality facilities (HFs) | 0.193 | 0.240 | −0.216 | - |

| Aspects | APA | NRM | Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | PI | (AD, PD) | d + r | d − r | (R, D) | ||

| Medical services (MS) | −0.439 | −0.018 | L, L | 101.194 | −0.565 | ID (+, −) | C |

| Medical facilities (MF) | 1.461 | 1.160 | H, H | 101.379 | −0.747 | ID (+, −) | A |

| Tour planning (TP) | −0.237 | 0.137 | L, H | 100.297 | 1.095 | D (+, +) | B |

| Hospitality facilities (HF) | −0.786 | −1.279 | L, L | 99.487 | 0.217 | D (+, +) | C |

| AI (Attention Indicator) | PI (Performance Indicator) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rank | MF[1] > TP[2] > MS[3] > HF[4] | MF[1] > TP[2] > MS[3] > HF[4] |

| Available paths | 1. TP[2] → MF[1] {N} 2. TP[2] → MS[3] → MF[1] {Y} 3. TP[2] → HF[4] → MF[1] {Y} 4. TP[2] → HF[4] → MS[3] → MF[1] {Y} | 1. TP[2] → MF[1] {N} 2. TP[2] → MS[3] → MF[1] {Y} 3. TP[2] → HF[4] → MF[1] {Y} 4. TP[2] → HF[4] → MS[3] → MF[1] {Y} |

| Suitable adoption paths | 2. TP → MS → MF 3. TP → HF → MF 4. TP → HF → MS → MF | |

| Aspects | APA | NRM | Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | PI | (AD, PD) | d + r | d − r | (R, D) | ||

| Reservation service (MS1) | −1.355 | −0.824 | L, L | 51.145 | 0.933 | D (+, +) | C |

| Treatment assessment (MS2) | −0.496 | −0.247 | L, L | 51.554 | −0.288 | ID (+, −) | C |

| Medical surgery (MS3) | 1.174 | 1.133 | H, H | 51.992 | −0.927 | ID (+, −) | A |

| Postoperative recovery (MS4) | −0.815 | −0.118 | L, L | 51.144 | 0.282 | D (+, +) | C |

| Aspects | MS1 | MS2 | MS3 | MS4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reservation service (MS1) | - | |||

| Treatment assessment (MS2) | −0.305 | - | ||

| Medical surgery (MS3) | −0.466 | −0.158 | - | |

| Postoperative recovery (MS4) | −0.163 | 0.142 | 0.303 | - |

| AI (Attention Indicator) | PI (Performance Indicator) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rank | MS3[1] > MS2[2] > MS4[3] > MS1[4] | MS3[1] >MS4[2] > MS2[3] > MS1[4] |

| Available paths | 1. MS1[4] → MS3[1]{N} 2. MS1[4] → MS2[2] → MS3[1]{N} 3. MS1[4] → MS4[3] → MS3[1]{N} 4. MS1[4] → MS4[3] → MS2[2] → MS3[1]{N} | 1. MS1[4] → MS3[1]{N} 2. MS1[4] → MS2[3] → MS3[1]{N} 3. MS1[4] → MS4[2] → MS3[1]{N} 4. MS1[4] → MS4[2] → MS2[3] → MS3[1]{Y} |

| Suitable adoption paths | - | |

| Aspects | APA | NRM | Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | PI | (AD, PD) | d + r | d − r | (R, D) | ||

| Surgical equipment (MF1) | 1.591 | 0.877 | H, H | 146.323 | −0.451 | ID (+, −) | A |

| Diagnosis facilities (MF2) | 1.296 | 1.069 | H, H | 145.934 | −1.176 | ID (+, −) | A |

| Medical equipment (MF3) | 1.517 | 1.839 | H, H | 147.370 | −0.169 | ID (+, −) | A |

| Medical examination facilities (MF4) | 0.560 | −0.183 | H, L | 144.526 | 1.796 | D (+, +) | D |

| Aspects | MF1 | MF2 | MF3 | MF4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical equipment (MF1) | - | |||

| Diagnosis facilities (MF2) | −0.182 | - | ||

| Medical equipment (MF3) | 0.072 | 0.253 | - | |

| Medical examination facilities (MF4) | 0.561 | 0.740 | 0.495 | - |

| AI (Attention Indicator) | PI (Performance Indicator) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rank | MF1[1] > MF3[2] > MF2[3] > MF4[4] | MF3[1] > MF2[2] > MF1[3] > MF4[4] |

| Available paths | 1. MF4[4] → MF2[3]{N} 2. MF4[4] → MF1[1] → MF2[3]{Y} 3. MF4[4] → MF3[2] → MF2[3]{Y} 4. MF4[4] → MF3[2] → MF1[1] → MF2[3]{Y} | 1. MF4[4] → MF2[2] {N} 2. MF4[4] → MF1[3] → MF2[2]{N} 3. MF4[4] → MF3[1] → MF2[2]{Y} 4. MF4[4] → MF3[1] → MF1[3] → MF2[2]{Y} |

| Suitable adoption paths | 3. MF4 → MF3 → MF2 4. MF4 → MF3 → MF1 → MF2 | |

| Aspects | APA | NRM | Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | PI | (AD, PD) | d + r | d − r | (R, D) | ||

| Intercity sightseeing (TP1) | 0.314 | 0.267 | H, H | 174.966 | 0.331 | D (+,+) | A |

| City tour (TP2) | −0.275 | −0.632 | L, L | 175.911 | 0.337 | D (+,+) | C |

| Reception service (TP3) | −0.348 | 0.684 | L, H | 177.304 | −0.401 | ID (+,−) | B |

| Traffic connection (TP4) | −0.496 | 0.106 | L, H | 176.637 | −0.267 | ID (+,−) | B |

| Aspects | TP1 | TP2 | TP3 | TP4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercity sightseeing (TP1) | - | |||

| City tour (TP2) | −0.003 | - | ||

| Reception service (TP3) | −0.181 | −0.186 | - | |

| Traffic connection (TP4) | −0.147 | −0.154 | 0.034 | - |

| AI (Attention Indicator) | PI (Performance Indicator) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rank | TP1[1] > TP2[2] > TP3[3] > TP4[4] | TP3[1] > TP1[2] > TP4[3] > TP2[4] |

| Available paths | 1. TP1[1] → TP3[3] {Y} 2. TP1[1] → TP4[4] → TP3[3] {Y} 3. TP1[1] → TP2[2] → TP3[3] {Y} 4. TP1[1] → TP2[2] → TP4[4] → TP3[3] {Y} | 1. TP1[2] → TP3[1] {N} 2. TP1[2] → TP4[3] → TP3[1] {Y} 3. TP1[2] → TP2[4] → TP3[1] {Y} 4. TP1[2] → TP2[4] → TP4[3] → TP3[1] {Y} |

| Suitable adoption paths | 2. TP1 → TP4 → TP3 3. TP1 → TP2 → TP3 4. TP1 → TP2 → TP4 → TP3 | |

| Aspects | APA | NRM | Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | PI | (AD, PD) | d + r | d − r | (R, D) | ||

| Accommodation facilities (HF1) | 0.290 | 0.427 | H, H | 198.268 | 0.851 | D (+, +) | A |

| Restaurant facilities (HF2) | −0.471 | −1.306 | L, L | 196.424 | 1.383 | D (+, +) | C |

| Emergency treatment (HF3) | −1.011 | −1.466 | L, L | 197.027 | −1.677 | ID (+, −) | C |

| Medical connection (HF4) | −1.477 | −1.627 | L, L | 198.132 | −0.557 | ID (+, −) | C |

| Aspects | HF1 | HF2 | HF3 | HF4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation facilities (HF1) | - | |||

| Restaurant facilities (HF2) | 0.138 | - | ||

| Emergency treatment (HF3) | −0.635 | −0.760 | - | |

| Medical connection (HF4) | −0.354 | −0.485 | 0.282 | - |

| AI (Attention Indicator) | PI (Performance Indicator) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rank | HF1[1] > HF2[2] > HF3[3] > HF4[4] | HF1[1] > HF2[2] > HF3[3] > HF4[4] |

| Available paths | 1. HF2[2] → HF3[3]{Y} 2. HF2[2] → HF4[4] → HF3[3]{Y} 3. HF2[2] → HF1[1] → HF3[3]{Y} 4. HF2[2] → HF1[1] → HF4[4] → HF3[3]{Y} | 1. HF2[2] → HF3[3]{Y} 2. HF2[2] → HF4[4] → HF3[3]{Y} 3. HF2[2] → HF1[1] → HF3[3]{Y} 4. HF2[2] → HF1[1] → HF4[4] → HF3[3]{Y} |

| Suitable adoption paths | 1. HF2 → HF3 2. HF2 → HF4 → HF3 3. HF2 → HF1 → HF3 4. HF2 → HF1 → HF4 → HF3 | |

| Aspects | Suitable Adoption Paths |

|---|---|

| MSs (medical services) | - |

| MFs (medical facilities) | 3. MF4 → MF3 → MF2 4. MF4 → MF3 → MF1 → MF2 |

| TP (tour planning) | 2. TP1 → TP4 → TP3 3. TP1 → TP2 → TP3 4. TP1 → TP2 → TP4 → TP3 |

| HFs (hospitality facilities) | 1. HF2 → HF3 2. HF2 → HF4 → HF3 3. HF2 → HF1 → HF3 4. HF2 → HF1 → HF4 → HF3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, C.-L.; Lin, C.-L. Exploring Service Needs and Development Strategies for the Healthcare Tourism Industry Through the APA-NRM Technique. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157068

Kuo C-L, Lin C-L. Exploring Service Needs and Development Strategies for the Healthcare Tourism Industry Through the APA-NRM Technique. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):7068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157068

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Chung-Ling, and Chia-Li Lin. 2025. "Exploring Service Needs and Development Strategies for the Healthcare Tourism Industry Through the APA-NRM Technique" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 7068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157068

APA StyleKuo, C.-L., & Lin, C.-L. (2025). Exploring Service Needs and Development Strategies for the Healthcare Tourism Industry Through the APA-NRM Technique. Sustainability, 17(15), 7068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157068