Including Citizens’ Perspective in Advancing Urban Green Infrastructure: A Design-Toolkit for Private Open Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Framework

2.1. Barriers to the Advancement of Urban Green Infrastructure

2.2. Managing the UGI as an Urban Common

2.3. Advancing UGI Through Citizen Engagement

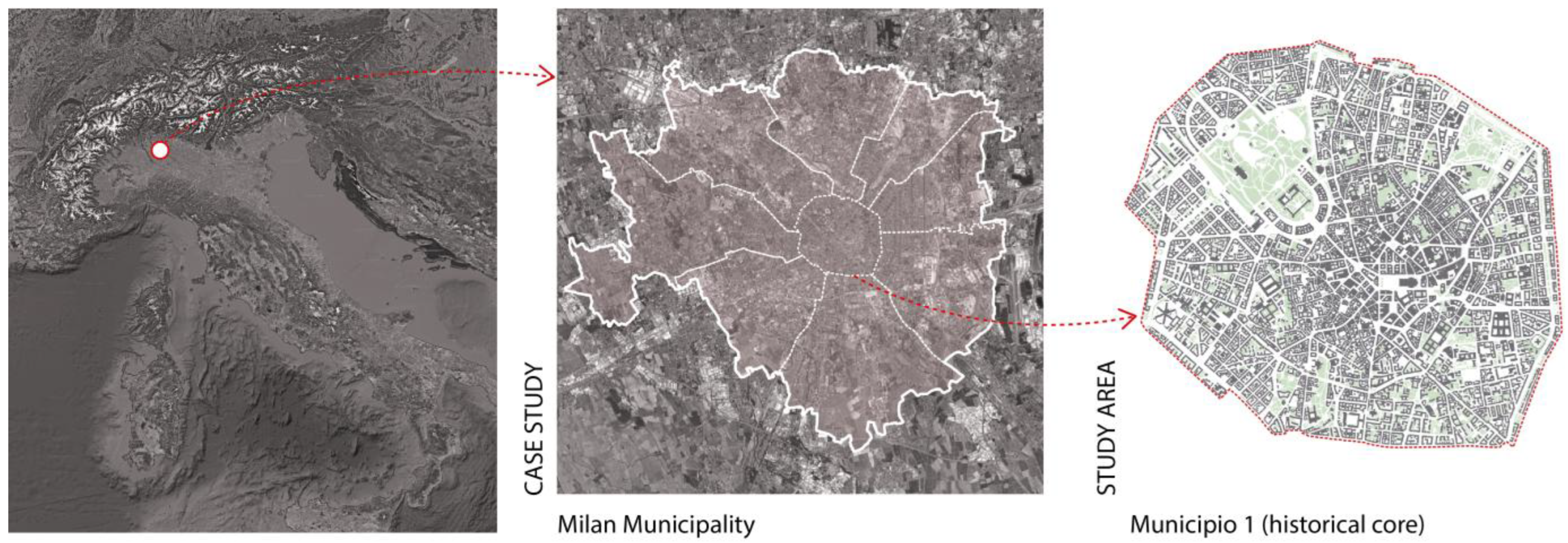

2.4. Case Study and Research Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Scope of the Research

- What are the perceived priorities regarding urban adaptation to climate change and the role of private spaces?

- What are the perceived risks associated with the implementation of NbSs in private open spaces?

- To what extent are citizens interested in playing an active role?

3.2. Methodology

- Focus groups were conducted within a selected community in early stages of the research to frame a preliminary investigation of the research topic with a target audience of experts or interested individuals.

- Questionnaires were distributed to a wide audience in the study area of Municipality 1 to record preferences and concerns about alternative solutions.

3.2.1. Focus Groups

3.2.2. Questionnaires

3.2.3. Design Toolkit

4. Results

4.1. Analytic Results of Social Investigation

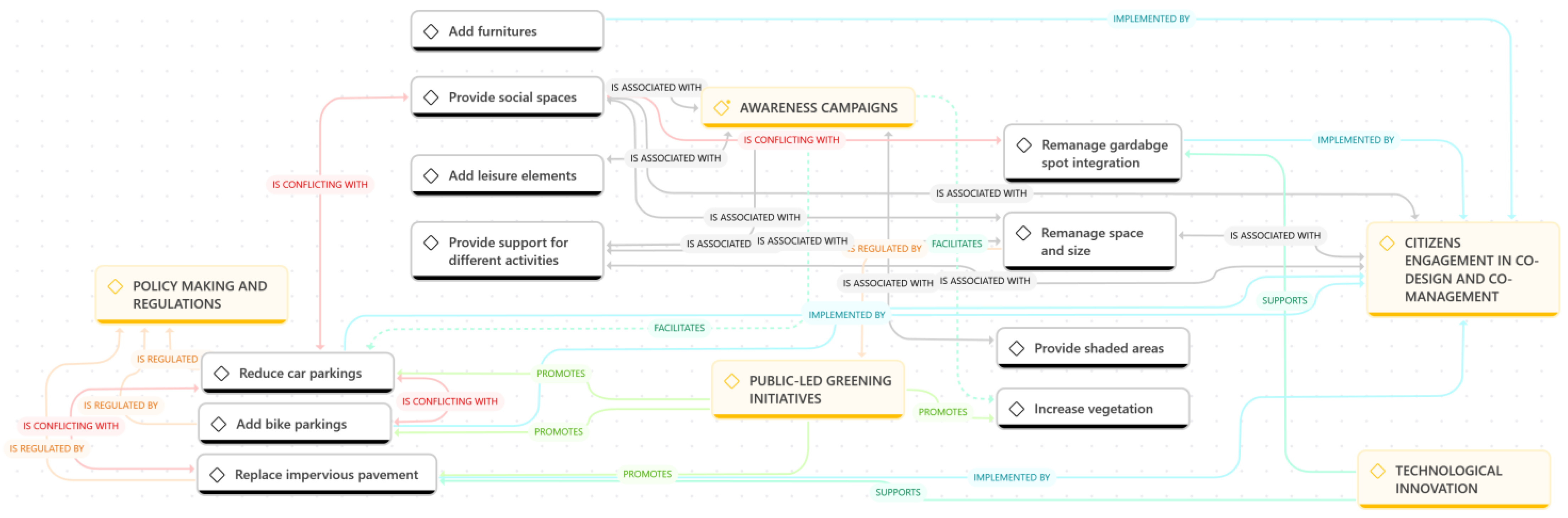

4.1.1. Focus Groups

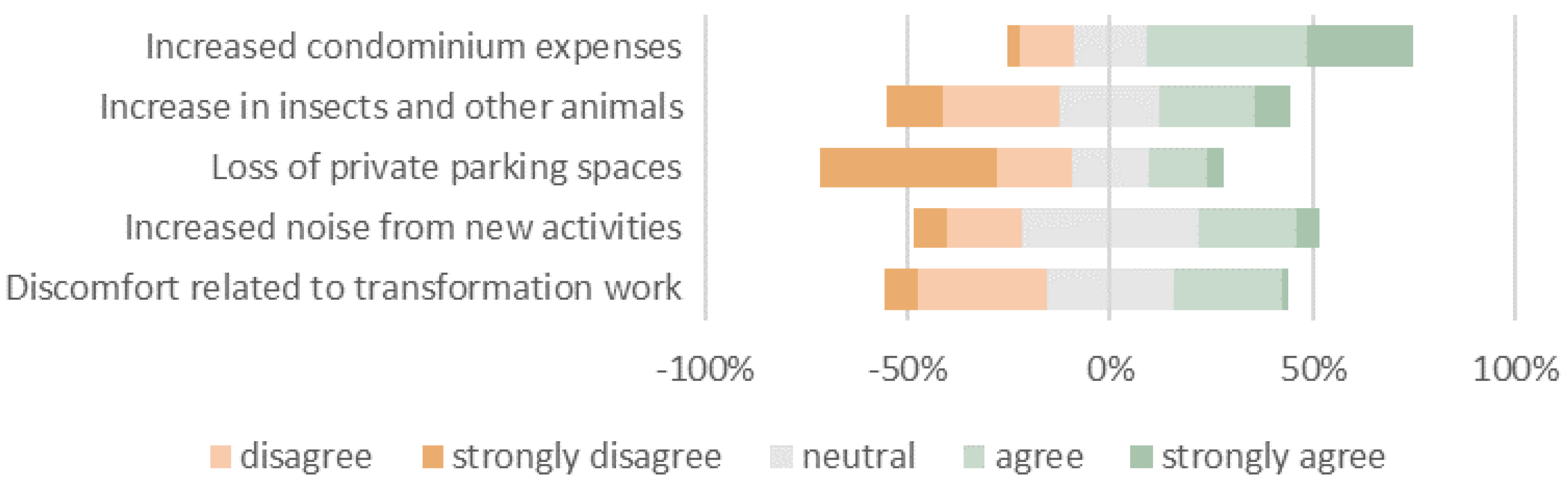

4.1.2. Questionnaires

4.2. Integrating Citizens’ Perspectives into a Design Toolkit

- The scale of application, classified into three classes defined on the quantiles of the size distribution of private open spaces within the study area: S < 125 m2; M 125–225 m2; L > 225 m2.

- The impact on a scale from 1 to 3: (1) solutions requiring integrated application with others for full functionality; (2) solutions applicable individually; (3) solutions individually applicable with high impact.

- The mode of application with respect to the courtyard space, i.e., whether it involves interventions on the ground, on the surrounding facades, on the building, or the incorporation of a furniture/technological element.

- The perceived priority to which the solution responds, referring to the five options recorded through the questionnaires (see Figure 6): (1) air quality improvement; (2) aesthetic improvement; (3) microclimate regulation; (4) biodiversity improvement; (5) fostering social cohesion; (6) support for food self-production.

- The contribution in terms of adaptation to CC: (1) contribution to ground water infiltration; (2) contribution to rainwater management; (3) enhancement of biodiversity; (4) mitigation of micro-climate; (5) contribution to circularity; (6) contrast to drought.

- The type of solution distinguished between green, gray, or hybrid.

- The contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

5. Discussion

- Greater recognition by public authorities of the strategic role of private open spaces and of active citizenship;

- Administrative and financial tools to facilitate and support private initiatives;

- Technical assistance and monitoring tools to ensure that private interventions are carried out properly;

- Ultimately, a long-term strategy in which public and private actions are planned in a complementary manner to achieve clearly defined urban adaptation goals.

6. Conclusions

- Further exploration of collaborative governance frameworks and public–private cooperation models that can support long-term co-management of green interventions on private land;

- Development of tools for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of small-scale NbSs in terms of ecosystem services, social impact, and cost-efficiency;

- Comparative studies across different urban contexts to assess how socio-demographic, cultural, and spatial variables affect residents’ willingness to engage in NbS implementation;

- Investigation of the conditions under which private spaces may evolve into forms of urban commons, through shared management or recognition of collective benefits.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Climate Change |

| ES | Ecosystem Services |

| EU | European Union |

| GI | Green Infrastructures |

| NbS | Nature-Based Solutions |

| PGT | Piano di Governo del Territorio (Territorial Government Plan) |

| PPP | Public–private Partnership |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UGI | Urban Green Infrastructures |

Appendix A

| QUESTION | TYPE | ANSWER OPTIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Which city are you from? | Open-ended | |

| Which urban Cultural Heritage layout best describes your city? | Multiple choice | ISOLATED BUILDINGS—There is not a defined historical center, some historical building are present within the urban environment |

| HISTORICAL CENTRE—The historical center is clearly defined and presents homogeneous characters | ||

| HISTORICAL DISTRICTS—Several different areas of historical interest are present within the urban environment | ||

| How would you rate the integration of the Urban Green Infrastructure in the historical urban area(s)? | Multiple choice | In the historical urban area(s), there is a severe lack of green spaces and connections |

| Only a few green spaces and green connections are present in the historical area(s) | ||

| The urban GI also fully involves the historical area(s) | ||

| The existing green spaces in the historical area(s) are mostly… | Multiple choice | Public green spaces |

| Private green spaces | ||

| I don’t know | ||

| Referring to the strategic plans of your city, is a further development of the existing UGI in historical areas planned? | Multiple choice | Yes |

| No | ||

| I don’t know | ||

| In your opinion, which are the main constraints to integrating GI into the historic areas of your city? | Multiple choice | Lack of public open space |

| Lack of a strategic plan | ||

| Lack of green solutions adapted to the historical context | ||

| Extreme fragility of the historical context | ||

| Lack of incentive policies for private initiative | ||

| How would you rate these action for the effective integration of the GI strategy into historical urban areas? [1: not important/5: very important] | Scale | Knowledge of the green history of the area |

| Coordination of private initiatives with the objectives identified by strategic planning | ||

| Differentiation of the UGI according to the characteristics of the context (including historical, cultural, architectural…) | ||

| Development of financial instruments to promote private initiative (for the integration of private spaces in the UGI) | ||

| Can you think of other actions to promote the integration of GI in historical districts? | Open-ended |

| QUESTION | TYPE | ANSWER OPTIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Do you live in Milano? | Binomial | Yes |

| No | ||

| If no, where do you currently live? | Open-ended | |

| Do you have a daily contact with nature? | Binomial | Yes |

| No | ||

| If yes, which of these modalities are part of your daily contact with nature? | Multiple choice | Looking |

| Passing through | ||

| Staying | ||

| Practicing | ||

| How do you rate the importance of nature in your daily life? [1: I don’t agree/5: I agree] | Scale | It helps me to relax and calm |

| It improves my mood | ||

| It improves my productivity and concentration | ||

| It allows me to do practical activities | ||

| Referring to the courtyard/private space of the house you live in, is there any kind of vegetation? | Multiple choice | No, not at all |

| Yes, but only vegetation in pots | ||

| Yes, only/also vegetation in the soil | ||

| Which actions are more relevant in your opinion? [1: not important/5: very important] | Scale | Trees and high vegetation to shadow |

| Improvement of soil permeability and ground vegetation | ||

| Furniture to allow people to stay (benches, tables…) | ||

| playground for children | ||

| Considering to transform private courtyards in green spaces, which of these limitations are more relevant in your opinion? [1: not important/5: very important] | Scale | Parking removal |

| Noise and/or dust for the transformation works (even if limited in time) | ||

| Vegetation brings more insects and other animals | ||

| costs of maintenance | ||

| Thinking about the courtyard/private space of your house, what you would like to change? | Open-ended |

Appendix B

| SECTION 1/3—COURTYARDS IN MILAN | |

|---|---|

| Question | Options |

| 1—What type of housing do you live in? | a—Single-family house |

| b—Duplex house | |

| c—Apartment in a residential building | |

| d—Other | |

| 2—Does your house have a courtyard/garden/open space (private or shared)? | Yes |

| No | |

| 3—Where is the courtyard/garden/open space place with respect to the building? | a—In front of the building |

| b—Around the building | |

| c—Within the block, accessible through a vehicle entrance | |

| d—Within the block, accessible through the building | |

| 4—What functions are present within your courtyard? | a—Car parking |

| b—Bike parking | |

| c—Waste collection | |

| d—Benches, tables, or other furniture | |

| e—Children’s playground | |

| f—Dehors or other extensions of private activities | |

| 5—How do you use the courtyard space? | a—Just passing through |

| b—To spend time outside | |

| c—To meet other people | |

| d—To park my car | |

| e—Other | |

| 6—How often do you use the space of the courtyard? | a—Daily |

| b—Several times a week | |

| c—Sporadically | |

| d—Rarely or never | |

| 7—How much do you think the presence of greenery within an urban courtyard is important (regardless of whether your courtyard has it or not)? [1: not important at all–5: very important] | |

| 8—Is there any greenery in your courtyard? | Yes |

| No | |

| 9—What kind of greenery? | a—Potted plants |

| b—One or more trees | |

| c—Natural surfaces (flowerbeds, grass…) | |

| d—Other | |

| 10—How do you evaluate the presence of greenery within your yard? [1: not satisfactory–5: very satisfactory] | a—Quantity: The amount of greenery present is adequate for the space available b—Quality: The types of greenery present are appropriate for the space available (potted plants, flower beds, trees) c—Impact: The greenery present enhances the perception of the courtyard space d—Accessibility: The greenery present is easily and directly accessible |

| SECTION 2/3—TRANSFORMATION SCENARIOS | |

| 11—Which of the interventions listed below would you like to carry out in your courtyard? [1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree] | a—Medium to tall trees for shading b—Accessible and usable green surfaces (grass and flower beds) c—Water elements for cooling (fountains, water ponds…) d—Vegetable gardens e—Green walls on the facades of buildings surrounding the courtyard f—Furniture for the usability of the space (chairs, tables, benches…) g—Children’s playground h—Outdoor sports equipment |

| 12—Which of the following criteria do you consider a priority? [1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree] | a—Absorption of pollutants and improvement of air quality |

| b—Aesthetic improvement of the courtyard | |

| c—Microclimate regulation (mainly mitigation of heat peak) | |

| d—Enhancement of biodiversity | |

| e—Fostering social interactions and strengthening a sense of community | |

| f—Support for food self-production | |

| 13—Which of the aspects listed below do you think might be a problem for you? [1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree] | a—Discomfort related to courtyard transformation work (noise, dust), even if for a limited period of time |

| b—Increased noise from new activities in the courtyard (recreational activities, children’s games...) | |

| c—Loss of private parking spaces | |

| d—Increase in insects and other animals due to the increased presence of vegetation | |

| e—Increased condominium expenses for the maintenance and care of the common space | |

| 14—Would you be willing to participate in community initiatives aimed at greening urban courtyards (e.g., volunteering for gardening, maintenance, or planting activities)? | Yes |

| No | |

| I don’t know | |

| 15—Would you support the regulated opening of your home’s courtyard to people not domiciled in the surrounding buildings? (the use by outside users is limited to certain time slots) | Yes |

| No | |

| I don’t know | |

| SECTION 3/3—GENERAL INFORMATION | |

| 16—In which district of Milan do you live? | |

| 17—In which neighborhood? | |

| 18—What is your age? | |

| 19—What gender do you identify with? | |

References

- Fang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Q. Integrating Green Infrastructure, Ecosystem Services and Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Sustainability: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Collier, M.J.; Kendal, D.; Bulkeley, H.; Dumitru, A.; Walsh, C.; Noble, K.; van Wyk, E.; Ordóñez, C.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Climate Change Adaptation: Linking Science, Policy, and Practice Communities for Evidence-Based Decision-Making. Bioscience 2019, 69, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyar, R.; Zarghami, E. Green Infrastructure Contribution for Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Landscape Context. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017, 15, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.; Singer, R. Urban Resilience in Climate Change. In Climate Change as a Threat to Peace: Impacts on Cultural Heritage and Cultural Diversity; von Schorlemer, S., Maus, S., Eds.; Peter Lang AG: Dresden, Germany, 2014; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Geneletti, D.; Cortinovis, C.; Zardo, L.; Esmail, B.A. Planning for Ecosystem Services in Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-20023-7. [Google Scholar]

- Thian, O.; Yeo, S.; Johari, M.; Yusof, M.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Zulhaidi, H.; Shafri, M.; Saito, K.; Yeo, L.B. ABC of Green Infrastructure Analysis and Planning: The Basic Ideas and Methodological Guidance Based on Landscape Ecological Principle. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; Cohen-Shacham, E., Janzen, C., Maginnis, S., Walters, G., Eds.; IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, H.M.; Kala, J.; Ng, A.W.M.; Muthukumaran, S. Effectiveness of Vegetated Patches as Green Infrastructure in Mitigating Urban Heat Island Effects during a Heatwave Event in the City of Melbourne. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2019, 25, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, L.; Parisi, S.G.; Cola, G.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Sanesi, G. Climatological Analysis of the Mitigating Effect of Vegetation on the Urban Heat Island of Milan, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 569–570, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petsinaris, F.; Baroni, L.; Georgi, B. Compendium of Nature-Based and “Grey” Solutions to Address Climate- and Water-Related Problems in European Cities EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation. 2020. Available online: https://growgreenproject.eu/compendium-nature-based-grey-solutions/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Jing, L.; Liang, Y. The Impact of Tree Clusters on Air Circulation and Pollutant Diffusion-Urban Micro Scale Environmental Simulation Based on ENVI-Met. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 657, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Bird, N.; Hallingberg, B.; Phillips, R.; Williams, D. The Role of Perceived Public and Private Green Space in Subjective Health and Wellbeing during and after the First Peak of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 211, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoic, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Use and Perceptions of Urban Green Space: An International Exploratory Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EEA. Nature-Based Solutions in Europe: Policy, Knowledge and Practice for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9480-362-7. [Google Scholar]

- McPhearson, T.; Andersson, E.; Elmqvist, T.; Frantzeskaki, N. Resilience of and through Urban Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Guidance on Integrating Ecosystems and Their Services into Decision-Making; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda. Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on ‘Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities’: (Full Version) for Nature-Based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C.; Hansen, R.; Rall, E.; Pauleit, S.; Lafortezza, R.; De Bellis, Y.; Santos, A.; Tosics, I. Green Infrastructure Planning and Implementation—The Status of European Green Space Planning and Implementation Based on an Analysis of Selected European City-Regions; 2015. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/40181512/Green_Infrastructure_Planning_and_Implem20151119-7989-1t000nc.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Pauleit, S.; Hansen, R.; Rall, E.L.; Zölch, T.; Andersson, E.; Luz, A.C.; Szaraz, L.; Tosics, I.; Vierikko, K. Urban Landscapes and Green Infrastructure. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Building a Green Infrastructure for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal COM/2019/640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Infrastructure (GI)—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital/* COM/2013/0249 Final */; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, L.M.; Good, K.D.; Moretti, M.; Kremer, P.; Wadzuk, B.; Traver, R.; Smith, V. Towards the Intentional Multifunctionality of Urban Green Infrastructure: A Paradox of Choice? npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R.; Bledsoe, B.P.; Ferreira, S.; Nibbelink, N.P. Challenges to Realizing the Potential of Nature-Based Solutions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 45, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; Bonn, A.; Kabisch, N.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; Bonn, A. Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas—Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice; Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxopeus, H.; Polzin, F. Reviewing Financing Barriers and Strategies for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüsken, L.M.; Slinger, J.H.; Vreugdenhil, H.S.I.; Altamirano, M.A. Money Talks. A Systems Perspective on Funding and Financing Barriers to Nature-Based Solutions. Nat.-Based Solut. 2024, 6, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekpour, S.; Tawfik, S.; Chesterfield, C. Designing Collaborative Governance for Nature-Based Solutions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casprini, D.; Oppio, A.; Rossi, G.; Bengo, I. Managing Urban Green Areas: The Benefits of Collaborative Governance for Green Spaces. Land 2023, 12, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia ud din, M.; Xu, Y.; Khan, N.U.; Han, H. Linking Local Collaborative Governance and Public Service Delivery: Mediating Role of Institutional Capacity Building. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. Ostrom in the City: Design Principles and Practices for the Urban Commons. In Routledge Handbook of the Study of the Commons; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.; Marshall, N. The Routledge Handbook of People and Place in the 21st-Century City; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. The City as a Commons. Yale Law Policy Rev. 2016, 34, 281–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesshöver, C.; Assmuth, T.; Irvine, K.N.; Rusch, G.M.; Waylen, K.A.; Delbaere, B.; Haase, D.; Jones-Walters, L.; Keune, H.; Kovacs, E.; et al. The Science, Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taura, F.; Ohme, M.; Shimatani, Y. Collaborative Development of Green Infrastructure: Urban Flood Control Measures on Small-Scale Private Lands. J. Disaster Res. 2021, 16, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari, J.R.; Arico, S.; Báldi, A.; et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework—Connecting Nature and People. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenveld, A.; Voorberg, W.; Van Buuren, A.; Hagen, L. A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Collaborative Governance Structures as Applied in Urban Gardens. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 1683–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ran, B.; Li, Y. Street-Level Collaborative Governance for Urban Regeneration: How Were Conflicts Resolved at Grassroot Level? J. Urban. Aff. 2024, 46, 1723–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Barthel, S.; Borgström, S.; Colding, J.; Elmqvist, T.; Folke, C.; Gren, Å. Reconnecting Cities to the Biosphere: Stewardship of Green Infrastructure and Urban Ecosystem Services. Ambio 2014, 43, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven Lessons for Planning Nature-Based Solutions in Cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschroth, F.; Kowarik, I. COVID-19 Crisis Demonstrates the Urgent Need for Urban Greenspaces. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 18, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mell, I.; Whitten, M. Access to Nature in a Post Covid-19 World: Opportunities for Green Infrastructure Financing, Distribution and Equitability in Urban Planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tansil, D.; Plecak, C.; Taczanowska, K.; Jiricka-Pürrer, A. Experience Them, Love Them, Protect Them—Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed People’s Perception of Urban and Suburban Green Spaces and Their Conservation Targets? Environ. Manag. 2022, 70, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.K.; Sparke, K. Self-Reported Well-Being and the Importance of Green Spaces—A Comparison of Garden Owners and Non-Garden Owners in Times of COVID-19. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 212, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, C.E.; Rieves, E.S.; Carlson, K. Perceptions of Green Space Usage, Abundance, and Quality of Green Space Were Associated with Better Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Residents of Denver. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H.J.P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, B. Analysis of Citizens’ Motivation and Participation Intention in Urban Planning. Cities 2020, 106, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.; Dubois, G.; Liquete, C.; Robuchon, M. Understanding Collaborative Governance of Biodiversity-Inclusive Urban Planning: Methodological Approach and Benchmarking Results for Urban Nature Plans in 10 European Cities. Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, G.; Errigo, F. Barcellona e Rotterdam Creative Cities: I Casi Del Pla Buits e Della Child Friendly City. In La Città Creativa. Spazi Pubblici e Luoghi Della Quotidianità; Galdini, R., Marata, A., Eds.; CNAPPC: Roma, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-88-941296-2-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. PLA BUITS Buits Urbans Amb Implicació Territorial i Social; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adjuntament de Barcelona. Pla d’Impuls a La Infraestructura Verda; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Camps-Calvet, M.; Langemeyer, J.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Gardens in Barcelona, Spain: Insights for Policy and Planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Hübner, S.; Kreutz, S.; Krüger, T. More City in the City—Working Together for More Quality Open Space in Hamburg [Mehr Stadt in Der Stadt—Gemeinsam Zu Mehr Freiraumqualität in Hamburg]; HafenCity Universität Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2013; Available online: https://repos.hcu-hamburg.de/handle/hcu/418 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Demaziere, C. Green City Branding or Achieving Sustainable Urban Development? Reflections of Two Winning Cities of the European Green Capital Award: Stockholm and Hamburg. Town Plan. Rev. 2020, 91, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitillo, P. Amburgo, Metropoli Verde. Territorio 1997, 4, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- CEC. OPEN SPACE 2021—Edinburgh’s Open Space Strategy; CEC: Edinburgh, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tillie, N.; Aarts, M.; Marijnissen, M.; Stenhuijs, L.; Borsboom, J.; Rietveld, E.; Doepel, D.; Visschers, J.; Lap, S. Rotterdam-People Make the Inner City: Densification + Greenification = Sustainable City; Cressie Communication Services; Tillie, N., Doepel, D., Stenhuijs, L., Rijke, C., Marijnissen, M., Borsboom, J., Eds.; Mediacenter Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom-Van Beurden, J.; Doepel, D.; Tillie, N. Sustainable Densification and Greenification in the Inner City of Rotterdam. In Proceedings of the CUPUM 2013—The International Conference on Computers in Urban Planning and Urban Management 13th edition, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2–5 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tillie, N.; Borsboom-van Beurden, J.; Doepel, D.; Aarts, M. Exploring a Stakeholder Based Urban Densification and Greening Agenda for Rotterdam Inner City—Accelerating the Transition to a Liveable Low Carbon City. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.; Morello, E. Are Nature-Based Solutions the Answer to Urban Sustainability Dilemma? The Case of CLEVER Cities CALs Within the Milanese Urban Context. In L’Urbanistica Italiana di Fronte all’Agenda Portare Territori e Comunità Sulla Strada Della Sostenibilità e Della Resilienza, Proceedings of the Atti Della XXII Conferenza Nazionale SIU; SIU Società Italiana degli Urbanisti: Matera, Italy, 2020; pp. 1322–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Sanesi, G.; Colangelo, G.; Lafortezza, R.; Calvo, E.; Davies, C. Urban Green Infrastructure and Urban Forests: A Case Study of the Metropolitan Area of Milan. Landsc. Res. 2016, 42, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I. Nature-Based Solutions across Spatial Urban Scales: Three Case Studies from Nice, Utrecht and Milan. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2024, 177, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canedoli, C.; Bullock, C.; Collier, M.J.; Joyce, D.; Padoa-Schioppa, E. Public Participatory Mapping of Cultural Ecosystem Services: Citizen Perception and Park Management in the Parco Nord of Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2017, 9, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Ovo, M.; Corsi, S. Urban Ecosystem Services to Support the Design Process in Urban Environment. A Case Study of the Municipality of Milan. Aestimum 2020, 2020, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Milano. Documento Degli Obiettivi per La Revisione Del Piano Di Governo Del Territorio Milano 2030; Comune di Milano: Milano, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, M.S. Networks and Fragments: An Integrative Approach for Planning Urban Green Infrastructures in Dense Urban Areas. Land 2024, 13, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, J.N.; Lux, M.S. Renaturing Historical Centres. The Role of Private Space in Milan’s Green Infrastrucutres. AGATHÓN Int. J. Archit. Art Des. 2022, 11, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.E.; Mattijssen, T.J.; Pn Van Der Jagt, A.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Andersson, E.; Elands, B.H.; Steen Møller, M. Active Citizenship for Urban Green Infrastructure: Fostering the Diversity and Dynamics of Citizen Contributions through Mosaic Governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastgo, P.; Hajzeri, A.; Ahmadi, E. Exploring the Opportunities and Constraints of Urban Small Green Spaces: An Investigation of Affordances. Child Geogr. 2024, 22, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerer, M.; Annighöfer, P.; Arzberger, S.; Burger, S.; Hecher, Y.; Knill, V.; Probst, B.; Suda, M. Urban Oases: The Social-Ecological Importance of Small Urban Green Spaces. Ecosyst. People 2024, 20, 2315991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilidis, A.A.; Popa, A.M.; Onose, D.A.; Gradinaru, S.R. Planning Small for Winning Big: Small Urban Green Space Distribution Patterns in an Expanding City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S. Methods in Urban Analysis; Baum, S., Ed.; Cities Research Series; Springer: Singapore, 2021; ISBN 978-981-16-1676-1. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. A Catalogue of Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Resilience; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, E.; Mahmoud, I.; Colaninno, N. Catalogue of Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Regeneration; Energy & Urban Planning Workshop, School of Architecture Urban Planning Construction Engineering, Politecnico di Milano: Milan, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.labsimurb.polimi.it/nbs-catalogue/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Mahmoud, I.; Morello, E. Co-Creation Pathway for Urban Nature-Based Solutions: Testing a Shared-Governance Approach in Three Cities and Nine Action Labs. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions; Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation; Andersson, I.; Ferreira, I.; Arlati, A.; Bradley, S.; Buijs, A.; Caitana, B.; Garcia-Mateo, M.-C.; Hilding-Hamann, K.E.; et al. Guidelines for Co-Creation and Co-Governance of Nature-Based Solutions: Insights Form EU-Funded Projects; Ferreira, I., Lupp, G., Mahmoud, I., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeente Rotterdam WeerWoord—Toolkit. Available online: https://rotterdamsweerwoord.nl/professionals/toolkit/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Lake Champlain Sea Grant. Absorb the Storm: Create a Rain-Friendly Yard and Neighborhood. A Guide for Residents Interested in Protecting Their Local Streams and Lake Champlain; Lake Champlain Sea Grant: Burlington, VT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Saving the Rain. Green Stormwater Solutions for Congregations; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Compendium of MS4 Permitting Approaches; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Popolazione Residente—Comune Di Milano. Available online: https://www.comune.milano.it/aree-tematiche/dati-statistici/pubblicazioni/popolazione-residente (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Lux, M.S.; Biraghi, C.A. Green Spaces Accessibility in Historic Urban Centres. In Networks, Markets & People; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1186 LNNS, pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartieri Resilienti—Milano Cambia Aria—Comune Di Milano. Available online: https://www.comune.milano.it/web/milano-cambia-aria/progetti/quartieri-resilienti (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Karam, G.; Hendel, M.; Cécilia, B.; Alexandre, B.; Patricia, B.; Laurent, R. The Oasis Project: UHI Mitigation Strategies Applied to Parisian Schoolyards. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Countermeasures to Urban Heat Islands, International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad, India, 2–4 December 2019; pp. 303–311. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04666841v1 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Alméstar, M.; Romero-Muñoz, S. (Re)Designing the Rules: Collaborative Planning and Institutional Innovation in Schoolyard Transformations in Madrid. Land 2025, 14, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Mas, M.; Continente, X.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; López, M.J. Community Use and Perceptions of Climate Shelters in Schoolyards in Barcelona. Int. J. Public Health 2025, 70, 1608083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, M.S.; Tzortzi, N. Green Fragments. Urban Courtyards Contribution to the Green Infrastructure of Historic Centres. In Urban Heritage and Climate Change. Issues and Challenges; Babalis, D., Ed.; Altralinea Edizioni: Florence, Italy, 2024; pp. 32–42. ISBN 9788898743315. [Google Scholar]

- Fior, M.; Galuzzi, P.; Vitillo, P. Well-Being, Greenery, and Active Mobility. Urban Design Proposals for a Network of Proximity Hubs along the New M4 Metro Line in Milan. TeMa—J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2022, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fior, M.; Galuzzi, P.; Vitillo, P. New Milan Metro-Line M4. From Infrastructural Project to Design Scenario Enabling Urban Resilience. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, A.; Simić, M. Green Public-Private Partnerships: Global and European Context and Best Practices. Technog. Green Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 2, 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Koppenjan, J.F.M. Public–Private Partnerships for Green Infrastructures. Tensions and Challenges. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 12, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Wen, J.; Du, S.; Zhang, M.; Ke, Q. Residents’ Willingness to Participate in Green Infrastructure: Spatial Differences and Influence Factors in Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, S.; Anton, B.; Wilk, B.; Latinos, V. Co-Designing Nature-Based Solutions in Living Labs—Deliverable D2.5: Final Report on Co-Design Workshops in Frontrunner Cities (Dortmund, Turin, and Zagreb); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Różewicz, D. Rotterdam’s Sustainability Strategy: A Case Study on Municipal Policies. Semest. Econ. 2020, 23, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Tilie, N. The Dynamics of Urban Ecosystem Governance in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Ambio 2014, 43, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillie, N.; van der Heijden, R. Advancing Urban Ecosystem Governance in Rotterdam: From Experimenting and Evidence Gathering to New Ways for Integrated Planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F. A Method Proposal to Adapt Urban Open-Built and Green Spaces to Climate Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, S. Community Engagement Challenges in Public Space Design: Lessons from the Spanish Cases. Planlama-Planning 2024, 34, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansão-Fontes, A.; Pesoa, M.; Araujo-Souza, A.; Sabaté, J.; Neves, L.; Sansão-Fontes, A.; Pesoa, M.; Araujo-Souza, A.; Sabaté, J.; Neves, L. Urbanismo Tático Como Teste Do Espaço Público: O Caso Das Superquadras de Barcelona. EURE 2019, 45, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Group | Mode | N. Participants | Participants Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st YADES Summer School | Online | 38 | Specialized/international |

| 2nd YADES Summer School | Hybrid in presence in Milan and online | 62 | Specialized or interested in the topic/mostly based in Milan |

| Population Size: 111,560 | Target | Total Answers | Complete Answers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 383 | 394 | 355 |

| Confidence level | 95% | 95% | 95% |

| Margin of error | 5% | 4.93% | 5.19% |

| Is the Quantity of Existing Greenery Satisfactory? (Q10a) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No n. Answers (Row%) | Yes n. Answers (Row%) | TOT | |

| Frequency of use (Q6) | |||

| Daily—Several times a week | 181 (77%) | 55 (23%) | 236 (100%) |

| Sporadically—Rarely or never | 67 (56%) | 52 (56%) | 119 (100%) |

| TOT | 248 (70%) | 107 (30%) | 355 |

| Is the Quality of Existing Greenery Satisfactory? (Q10b) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No n. Answers (Row%) | Yes n. Answers (Row%) | TOT | |

| Frequency of use (Q6) | |||

| Daily—Several times a week | 155 (77%) | 81 (23%) | 236 (100%) |

| Sporadically—Rarely or never | 61 (51%) | 58 (49%) | 119 (100%) |

| TOT | 216 (61%) | 139 (39%) | 355 |

| Is There any Greenery in Your Courtyard? (Q8) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No n. Answers (Col.%) | Yes n. Answers (Col.%) | TOT | |

| Frequency of use (Q6) | |||

| Daily—Several times a week | 27 (52%) | 209 (69%) | 236 (66%) |

| Sporadically—Rarely or never | 25 (48%) | 94 (31%) | 119 (34%) |

| TOT | 52 (100%) | 303 (100%) | 355 |

| Estimate | S.E. | Odds Ratio | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q10a | 18–25 | −0.4336 | 0.2170 | 0.04568 * | |

| 26–35 | −0.4827 | 0.2897 | 0.6171149 | 0.09572 | |

| 36–50 | −1.2246 | 0.3825 | 0.2938752 | 0.00137 ** | |

| 51–65 | 0.1574 | 0.3564 | 1.170464 | 0.65879 | |

| >65 | −15.3770 | 621.6501 | 2.098233 × 10−7 | 0.98027 | |

| Q13e | 18–25 | −0.4336 | 0.2170 | 0.045684 * | |

| 26–35 | 0.9405 | 0.2813 | 2.561262 | 0.000829 *** | |

| 36–50 | 2.8760 | 0.4778 | 17.74316 | 1.75 × 10−9 *** | |

| 51–65 | 1.6123 | 0.3950 | 5.014331 | 4.48 × 10−5 *** | |

| >65 | 16.2443 | 621.6501 | 11,345,140 | 0.979153 | |

| Q14 | 18–25 | 0.24846 | 0.21364 | 0.245 | |

| 26–35 | 0.29054 | 0.27920 | 1.337149 | 0.298 | |

| 36–50 | 1.62334 | 0.40128 | 5.069996 | 5.22 × 10−5 *** | |

| 51–65 | −0.20924 | 0.35228 | 0.8112005 | 0.553 | |

| >65 | 0.03922 | 0.79308 | 1.039999 | 0.961 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lux, M.S. Including Citizens’ Perspective in Advancing Urban Green Infrastructure: A Design-Toolkit for Private Open Spaces. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156781

Lux MS. Including Citizens’ Perspective in Advancing Urban Green Infrastructure: A Design-Toolkit for Private Open Spaces. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156781

Chicago/Turabian StyleLux, Maria Stella. 2025. "Including Citizens’ Perspective in Advancing Urban Green Infrastructure: A Design-Toolkit for Private Open Spaces" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156781

APA StyleLux, M. S. (2025). Including Citizens’ Perspective in Advancing Urban Green Infrastructure: A Design-Toolkit for Private Open Spaces. Sustainability, 17(15), 6781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156781