Mediating Power of Place Attachment for Urban Residents’ Well-Being in Community Cohesion

Abstract

1. Introduction

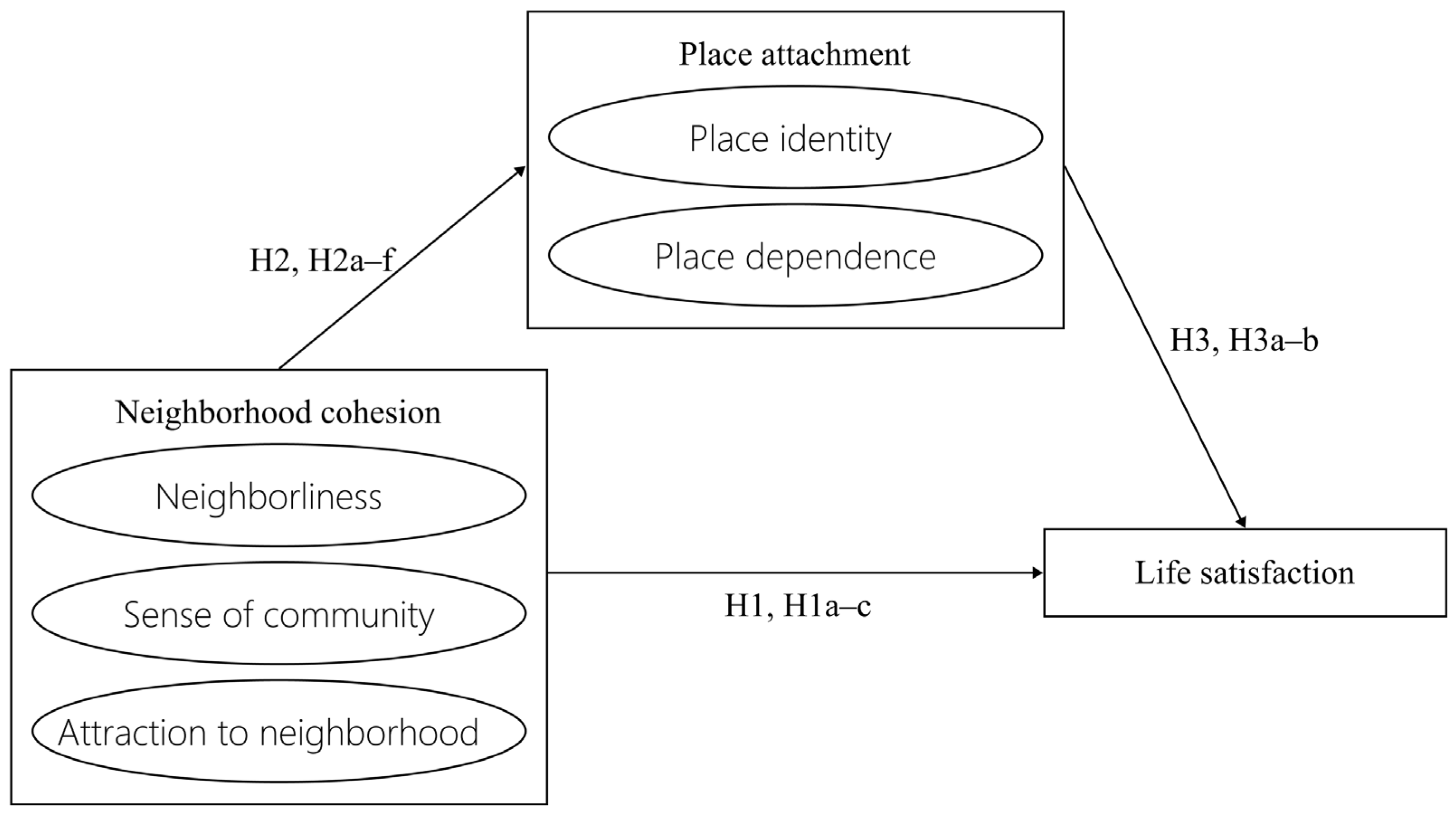

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Life Satisfaction

2.2. The Mediating Role of Place Attachment

2.3. Research Models and Hypotheses

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Measurement Model

4.2. Result of the Structural Model

4.2.1. Assessing the Model’s Explanatory Ability

4.2.2. Path Coefficient Assessment

4.2.3. Assessing the Mediating Roles of Place Identity and Place Dependence

4.2.4. Testing Overall Mediating Effect of Place Attachment

4.3. Subgroup Analysis Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of the Results

5.2. Variations Across Subgroups

5.3. Implications for Research

5.4. Implications for Practice

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item | |

|---|---|---|

| Neighbourhood cohesion, NC [17,18] | ||

| Neighbourliness | NEI1 | I visit with my neighbours in their homes. |

| NEI2 | The friendships l have with people in my neighbourhood mean a lot. | |

| NEI3 | If l need advice, l could go to someone in my neighbourhood. | |

| NEI4 | I borrow things and exchange favours with my neighbours. | |

| Sense of community | SOC1 | I believe my neighbours would help me in an emergency. |

| SOC2 | I feel loyal to people in my neighbourhood. | |

| SOC3 | I’d be willing to work with others to improve my neighbourhood. | |

| SOC4 | I think of myself as similar to people who live in this neighbourhood. | |

| SOC5 | A feeling of fellowship runs deep in this neighbourhood. | |

| SOC6 | I regularly stop to talk with people in my neighbourhood. | |

| SOC7 | Living in this neighbourhood gives me a sense of community. | |

| Attraction to neighbourhood | ATTR1 | Overall, l am very attracted to living in this neighbourhood. |

| ATTR2 | I feel like l belong to this neighbourhood. | |

| ATTR3 | I plan to remain a resident of this neighbourhood for a number of years. | |

| Place attachment, PA [34,52] | ||

| Place identity | PI1 | I feel the community where I currently is a part of me. |

| PI2 | The community where I currently is very special to me. | |

| PI3 | I identify strongly with the community where I currently. | |

| PI4 | I am very attached to the community where I currently. | |

| PI5 | Visiting the community where I currently says a lot about who l am. | |

| PI6 | The community where I currently means a lot to me. | |

| Place dependence | PD1 | The community where I currently, is the best place for what I like to do. |

| PD2 | No other place can compare to the community where I currently. | |

| PD3 | I get more satisfaction out of visiting the community where I currently than any other. | |

| PD4 | Doing what I do at the community where I currently is more important to me than doing it in any other place. | |

| PD5 | I wouldn’t substitute any other area for doing the types of things I do at the community where I currently. | |

| Life satisfaction, LS [13,54] | ||

| LS1 | In most ways my life is close to my ideal. | |

| LS2 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | |

| LS3 | I am satisfied with my life. | |

| LS4 | So far I have gotten the important things I want in life. | |

| LS5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. | |

References

- Ye, L.; Peng, X.; Aniche, L.Q.; Scholten, P.H.T.; Ensenado, E.M. Urban Renewal as Policy Innovation in China: From Growth Stimulation to Sustainable Development. Public Adm. Dev. 2021, 41, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, O.C.; Cifci, I.; Tiwari, S. Residents’ Entrepreneurship Motives, Attitude, and Behavioral Intention toward the Meal-Sharing Economy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Micro-Regeneration in Shanghai and the Public-Isation of Space. Habitat Int. 2023, 132, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Changing Neighbourhood Cohesion under the Impact of Urban Redevelopment: A Case Study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Lu, T.; Fu, T. Intra-Urban Migration and Perceptions of Neighborhood Cohesion in Urban China: The Case of Guangzhou. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2023, 32, 521–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. How to Alleviate Alienation from the Perspective of Urban Community Public Space—Evidence from Urban Young Residents in China. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opit, S.; Witten, K.; Kearns, R. Housing Pathways, Aspirations and Preferences of Young Adults within Increasing Urban Density. Hous. Stud. 2020, 35, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shen, D. Analysis on the Current Situation, Problems and Paths of Social Participation of Contemporary Chinese Youth. Chin. Youth Stud. 2018, 5, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Research on the Social Participation of China’s “Post-90s” Youths. Youth Stud. 2021, 4, 11–23+94. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G.; Wu, W. The Role of Stakeholders and Their Participation Network in Decision-Making of Urban Renewal in China: The Case of Chongqing. Cities 2019, 92, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Cadaval, S.; Wallace, C.; Anderson, E.; Egerer, M.; Dinkins, L.; Platero, R. Factors That Enhance or Hinder Social Cohesion in Urban Greenspaces: A Literature Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, S.; Bai, X. Ageing in China: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities. In Aging Across Cultures: Growing Old in the Non-Western World; Selin, H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Portero, C.; Alarcón, D.; Barrios Padura, Á. Dwelling Conditions and Life Satisfaction of Older People through Residential Satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Cheung, O.; Leung, J.; Tong, C.; Lau, K.; Cheung, J.; Woo, J. Is Neighbourhood Social Cohesion Associated with Subjective Well-Being for Older Chinese People? The Neighbourhood Social Cohesion Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahnow, R.; Tsai, A. Crime Victimization, Place Attachment, and the Moderating Role of Neighborhood Social Ties and Neighboring Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Leung, G.; Chan, J.; Yip, B.H.K.; Wong, S.; Kwok, T.; Woo, J. Neighborhood Social Cohesion Associates with Loneliness Differently among Older People According to Subjective Social Status. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humble, S.; Sharma, A.; Rangaraju, B.; Dixon, P.; Pennington, M. Associations between Neighbourhood Social Cohesion and Subjective Well-Being in Two Different Informal Settlement Types in Delhi, India: A Quantitative Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Searle, M. Conceptualization and Validation of the Neighbourhood Cohesion Index Using Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling. Community Dev. J. 2021, 56, 408–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Neighborhood Relations among Community Residents—An Empirical Analysis Based on CGSS2018. Adv. Appl. Math. 2022, 11, 8412–8416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Lu, T.; Luo, X. Urban Enclosure, Neighbourhood Commons, and Community Participation Willingness: Evidence from Shanghai, China. Geoforum 2023, 141, 103719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, J.; Li, X. Decoding Vibrant Neighborhoods: Disparities between Formal Neighborhoods and Urban Villages in Eye-Level Perceptions and Physical Environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Kawachi, I.; Glymour, M.M. Social Epidemiology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, A. Intergroup Contact Theory: Recent Developments and Future Directions. Soc. Justice Res. 2018, 31, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; To, H.-P.; Chan, E. Reconsidering Social Cohesion: Developing a Definition and Analytical Framework for Empirical Research. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 75, 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.; Haddock, G.; Campodonico, C.; Haarmans, M.; Varese, F. The Influence of Romantic Relationships on Mental Wellbeing for People Who Experience Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 86, 102022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, J.; Dragolov, G. Happier Together. Social Cohesion and Subjective Well-Being in Europe. Int. J. Psychol. 2016, 51, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinette, J.W.; Charles, S.T.; Mogle, J.A.; Almeida, D.M. Neighborhood Cohesion and Daily Well-Being: Results from a Diary Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 96, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, P.J. Natural Neighborhood Networks—Important Social Networks in the Lives of Older Adults Aging in Place. J. Aging Stud. 2011, 25, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Kawachi, I. Perceived Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Preventive Healthcare Use. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, e35–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratidis, K. Commute Satisfaction, Neighborhood Satisfaction, and Housing Satisfaction as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being and Indicators of Urban Livability. Travel Behav. Soc. 2020, 21, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Dong, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W. Does Satisfactory Neighbourhood Environment Lead to a Satisfying Life? An Investigation of the Association between Neighbourhood Environment and Life Satisfaction in Beijing. Cities 2018, 74, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. What Makes Cities Livable? Determinants of Neighborhood Satisfaction and Neighborhood Happiness in Different Contexts. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, J.; Fan, Y.; Ramaswami, A. How Do Neighborhood Attributes Relate to Life Satisfaction and Neighborhood Satisfaction Differently? Findings 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Fu, X.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D.A. The Influence of Place Attachment on Social Distance: Examining Mediating Effects of Emotional Solidarity and the Moderating Role of Interaction. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 828–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.W. Measuring Place Attachment: Some Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the NRPA Symposium on Leisure Research, San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–24 October 1989; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Lin, B.; Sun, J. Authenticity, Identity, Self-Improvement, and Responsibility at Heritage Sites: The Local Residents’ Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2024, 102, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, C.; Styvén, M.E. The Multidimensionality of Place Identity: A Systematic Concept Analysis and Framework of Place-Related Identity Elements. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; Shumaker, S.A. People in places: A Transactional View of Settings. In Cognition, Social Behavior and the Environment; Harvey, J.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 441–488. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.L.; Graefe, A.R. Attachments to Recreation Settings: The Case of Rail—Trail Users. Leis. Sci. 1994, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Pathways of Place Dependence and Place Identity Influencing Recycling in the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-J.; Tsou, C.-W.; Li, Y.-S. Urban-Greenway Factors’ Influence on Older Adults’ Psychological Well-Being: A Case Study of Taichung, Taiwan. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Van Dijk, T.; Tang, J.; van den Berg, A.E. Green Space Attachment and Health: A Comparative Study in Two Urban Neighborhoods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14342–14363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricchiolo, F.; Mosca, O.; Paolini, D.; Fornara, F. The Mediating Role of Place Attachment Dimensions in the Relationship Between Local Social Identity and Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 645648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandotiya, R.; Aggarwal, A. An Examination of Tourists’ National Identity, Place Attachment and Loyalty at a Dark Tourist Destination. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 6063–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.P.; Van Den Berg, P.E.; Kemperman, A.D.; Mohammadi, M. Social Impacts of Living in High-Rise Apartment Buildings: The Effects of Buildings and Neighborhoods. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. What Makes Neighborhood Different from Home and City? Effects of Place Scale on Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodori, G.L. Examining the Effects of Community Satisfaction and Attachment on Individual Well-Being. Rural Sociol. 2001, 66, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, B.; Dunne, M.; Armstrong, R. Sample Size Estimation and Statistical Power Analyses. Optom. Today 2010, 16, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fone, D.L.; Farewell, D.M.; Dunstan, F.D. An Ecometric Analysis of Neighbourhood Cohesion. Popul. Health Metr. 2006, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, H.; Li, Z.; Gou, F.; Zhai, W. Can Green Space Exposure Enhance the Health of Rural Migrants in Wuhan, China? An Exploration of the Multidimensional Roles of Place Attachment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 93, 128228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wu, C.; Zheng, R.; Ren, X. The Psychometric Evaluation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale Using a Nationally Representative Sample of China. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in Second Language and Education Research: Guidelines Using an Applied Example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesen, R.; Bright, L.K.; Zucker, A. Vindicating Methodological Triangulation. Synthese 2019, 196, 3067–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryon, W.W. Evaluating Statistical Difference, Equivalence, and Indeterminacy Using Inferential Confidence Intervals: An Integrated Alternative Method of Conducting Null Hypothesis Statistical Tests. Psychol. Methods 2001, 6, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K. PLS’ Janus Face—Response to Professor Rigdon’s ‘Rethinking Partial Least Squares Modeling: In Praise of Simple Methods’. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.N. Multimethod Factor Analysis in the Evaluation of Convergent and Discriminant Validity. Psychol. Bull. 1969, 72, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Shen, X.; Li, L. Is AI Food a Gimmick or the Future Direction of Food Production?—Predicting Consumers’ Willingness to Buy AI Food Based on Cognitive Trust and Affective Trust. Foods 2024, 13, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, N.d.; de Carvalho-Ferreira, J.P.; Beghini, J.; da Cunha, D.T. The Psychological Impact of the Widespread Availability of Palatable Foods Predicts Uncontrolled and Emotional Eating in Adults. Foods 2024, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmerón, R.; García, C.B.; García, J. Variance Inflation Factor and Condition Number in Multiple Linear Regression. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2018, 88, 2365–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westland, J.C. Structural Equation Models: From Paths to Networks; Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Larson, K.L.; Pfeiffer, D.; Rosales Chavez, J.-B. Planning for Urban Sustainability through Residents’ Wellbeing: The Effects of Nature Interactions, Social Capital, and Socio-Demographic Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Chi, C.G.-Q.; Chiappa, G.D. How Sense of Community and Social Environment Influence Residents’ Subjective Well-Being? Moderating Role of Trust. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2025, 26, 457–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Perceived Residential Environment of Neighborhood and Subjective Well-Being among the Elderly in China: A Mediating Role of Sense of Community. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.A.; Thomas, H.J.; Pelecanos, A.M.; Najman, J.M.; Scott, J.G. Attachment in Young Adults and Life Satisfaction at Age 30: A Birth Cohort Study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2024, 19, 1549–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.Y.; Sinha, M.; Concepcion, T.; Patton, G.; Way, T.; McCay, L.; Mensa-Kwao, A.; Herrman, H.; De Leeuw, E.; Anand, N.; et al. Making Cities Mental Health Friendly for Adolescents and Young Adults. Nature 2024, 627, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.; Prendergast, K.; Aoyagi, M.; Burningham, K.; Hasan, M.M.; Hayward, B.; Jackson, T.; Jha, V.; Mattar, H.; Schudel, I.; et al. Young People and Environmental Affordances in Urban Sustainable Development: Insights into Transport and Green and Public Space in Seven Cities. Sustain. Earth 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, X.; Lukosch, S.; Brazier, F. Social Cohesion Revisited: A New Definition and How to Characterize It. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 32, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.A.; Streeter, R.; Abrams, S.J.; Lee, B.; Popky, D. Public Places and Commercial Spaces: How Neighborhood Amenities Foster Trust and Connection in American Communities. 2021. Available online: https://www.americansurveycenter.org/research/public-places-and-commercial-spaces-how-neighborhood-amenities-foster-trust-and-connection-in-american-communities/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Hirvonen, J.; Lilius, J. Do Neighbour Relationships Still Matter? J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 1023–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortright, J. Youth Movement: A Generational Shift in Preference for Urbanism. City Observatory. Available online: https://cityobservatory.org/youth_movement_june2020 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Holden, M. Community Well-Being in Neighbourhoods: Achieving Community and Open-Minded Space through Engagement in Neighbourhoods. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2018, 1, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ye, L.; Song, W.; Tu, Z. A Study on the Pattern of Spatial and Temporal Differentiation in Housing Burden and Migration of Urban Migrants in China. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. 2023, 57, 576–588+598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, H. Urban Environmental Exposure and Migrant Health in the Age of Mobility—A Socio-Spatial Effects-Based Perspective. Shanghai Urban Plan. 2023, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Making Cities More “Youth Friendly”—Hubei Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. Available online: https://zjt.hubei.gov.cn/bmdt/dtyw/szsm/202408/t20240816_5305055.shtml (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Lu, X. The Model, Concept and Structure of Community Governance in Japan—An Analysis Centered on the Hybrid Model. Jpn. Stud. 2015, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, S. Collective Forms and Collective Spaces: A Discussion of Urban Design Thinking and Practice Based on Research in Chinese Cities. China City Plan. Rev. 2019, 4, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Liu, P. A Study of Heterogeneous Social Structure and Neighborhood/Neighborhood Relationships in Chinese Urban Communities. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Lin, Z.; Vojnovic, I.; Qi, J.; Wu, R.; Xie, D. Social Environments Still Matter: The Role of Physical and Social Environments in Place Attachment in a Transitional City, Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 232, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babintsev, V.P. Youth In Space Of Transforming Urban Culture; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; pp. 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.; Knudsen, L.B.; Arp, M.; Skov, H. Zones of Belonging-Experiences from a Danish Study on Belonging, Local Community and Mobility. Geoforum Perspekt. 2016, 15, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Krekel, C.; MacKerron, G. How Environmental Quality Affects Our Happiness. World Happiness Rep. 2020, 95, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Ma, J.; Tao, S. Exploring the Relationships among Commute, Work and Life Satisfaction: A Multiscale Analysis in Beijing. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 118, 103946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, J. Disembedding and Re-Embedding: The Online Interaction Mechanisms of Divorced Youth in China. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1413129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quackenbush, D.M.; Krasner, A. Avatar Therapy: Where Technology, Symbols, Culture, and Connection Collide. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2012, 18, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X. How Does Social Capital Affect Residents’ Subjective Well-Being?—Empirical Evidence from the China Social Comprehensive Survey. J. Party Sch. Ningbo Munic. Comm. Communist Party China 2021, 43, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Chen, J. Residential Mobility and Post-Move Community Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Land 2021, 10, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Wu, Y.; MacLachlan, I.; Zhu, J. The Role of Social Capital in the Collective-Led Development of Urbanising Villages in China: The Case of Shenzhen. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 3335–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, J. Exploring the Association between the Settlement Environment and Residents’ Positive Sentiments in Urban Villages and Formal Settlements in Shenzhen. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu, B.A. Theoretical Investigation of the Relationship Between Place Attachment and Well-Being-ProQuest; Middle East Technical University: Ankara, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, T. Attachment Orientations, Emotion Goals, and Emotion Regulation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 204, 112059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Vasconcelos, A.C. Understanding the Relationship between Urban Public Space and Social Cohesion: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2024, 7, 155–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, P.K.H.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Xie, L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Lau, J.T.F. Communication in Social Networking Sites on Offline and Online Social Support and Life Satisfaction Among University Students: Tie Strength Matters. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 74, 971–979. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, R.A.; Stuart, J.; Barber, B.L. Young Adults’ Perceptions of Their Online versus Offline Interactions with Close Friends: An Exploration of Individual Differences. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 14, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalle, M.; Di Marco, N.; Etta, G.; Sangiorgio, E.; Alipour, S.; Bonetti, A.; Alvisi, L.; Scala, A.; Baronchelli, A.; Cinelli, M.; et al. Persistent Interaction Patterns across Social Media Platforms and over Time. Nature 2024, 628, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirocchi, S. Generation Z, Values, and Media: From Influencers to BeReal, between Visibility and Authenticity. Front. Sociol. 2024, 8, 1304093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandauko, E.; Baiden, P.; Arku, G.; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Kutor, S.K.; Akyea, T. Sense of Community (SOC) in Gated Urban Neighborhoods: Empirical Insights from Accra, Ghana. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, J.; Tao, S. Examining the Nonlinear Relationship between Neighborhood Environment and Residents’ Health. Cities 2024, 152, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. From Renewal to Revitalization-Research and Practice on Stock Asset Enhancement Strategies in Urban Core Areas. New Constr. 2020, 4, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Yuanfen New Village Urban Village Organic Renewal Project Wins National Promotion. Available online: https://www.szlhq.gov.cn/gkmlpt/content/11/11132/post_11132272.html#4745 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Lin, Y.; De Meulder, B.; Wang, S. Understanding the ‘Village in the City’ in Guangzhou: Economic Integration and Development Issue and Their Implications for the Urban Migrant. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 3583–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Pan, Y.; Xu, Q. Space Diversification Process and Evolution Mechanism of Typical Village in the Suburbs of Guangzhou: A Case Study of Beicun. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1155–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhai, G.; Bilan, S. Assessment of Resident Happiness under Uncertainty of Economic Policies: Empirical Evidences from China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ruiz, V.-R.; Huete-Alcocer, N.; Alfaro-Navarro, J.; Nevado-Pea, D. The Relationship between Happiness and Quality of Life: A Model for Spanish Society. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 96 | 31.89 |

| Female | 205 | 68.10 | |

| Age | 18–25 years old | 246 | 81.73 |

| 26–35 years old | 42 | 13.95 | |

| 36–45 years old | 4 | 1.32 | |

| 46–60 years old | 9 | 2.99 | |

| Education Level | High school and vocational senior high school or below | 18 | 5.98 |

| College diploma or undergraduates | 205 | 68.11 | |

| Postgraduate research or above | 78 | 25.91 | |

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 275 | 91.36 |

| Married | 26 | 8.64 | |

| Duration of residence | 3 months or below | 30 | 9.97 |

| 3–6 months | 28 | 9.30 | |

| 6–12 months | 37 | 12.29 | |

| 12 months or above | 206 | 68.44 | |

| Status of Residence | Local residents | 124 | 41.20 |

| Remote residents | 177 | 58.80 | |

| City of Residence | Guangdong | 193 | 64.12 |

| Beijing | 10 | 3.32 | |

| Fujian | 9 | 2.99 | |

| Hunan | 8 | 2.66 | |

| Tianjin | 8 | 2.66 | |

| Hubei | 7 | 2.33 | |

| Jiangsu | 7 | 2.33 | |

| Henan | 6 | 1.99 | |

| Hebei | 6 | 1.99 | |

| Zhejiang | 6 | 1.99 | |

| Chongqing | 5 | 1.66 | |

| Heilongjiang | 4 | 1.33 | |

| Shandong | 4 | 1.33 | |

| Jiangxi | 4 | 1.33 | |

| Shanxi | 4 | 1.33 | |

| Shanghai | 4 | 1.33 | |

| Sichuan | 4 | 1.33 | |

| Guangxi | 3 | 1.00 | |

| Guizhou | 2 | 0.66 | |

| Hong Kong | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Xinjiang | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Yunnan | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Anhui | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Jilin | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Liaoning | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Neimenggu | 1 | 0.33 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | rho_A | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood cohesion (NC) | Neighborliness | NEI1 | 0.792 | 0.869 | 0.903 | 0.700 |

| NEI2 | 0.858 | |||||

| NEI3 | 0.845 | |||||

| NEI4 | 0.850 | |||||

| Sense of community | SOC1 | 0.768 | 0.913 | 0.926 | 0.644 | |

| SOC2 | 0.840 | |||||

| SOC3 | 0.731 | |||||

| SOC4 | 0.785 | |||||

| SOC5 | 0.857 | |||||

| SOC6 | 0.785 | |||||

| SOC7 | 0.841 | |||||

| Attraction to neighborhood | ATTR1 | 0.889 | 0.846 | 0.902 | 0.754 | |

| ATTR2 | 0.905 | |||||

| ATTR3 | 0.808 | |||||

| Place attachment (PA) | Place identity | PI1 | 0.848 | 0.929 | 0.944 | 0.736 |

| PI2 | 0.865 | |||||

| PI3 | 0.900 | |||||

| PI4 | 0.872 | |||||

| PI5 | 0.830 | |||||

| PI6 | 0.831 | |||||

| Place dependence | PD1 | 0.790 | 0.908 | 0.931 | 0.730 | |

| PD2 | 0.875 | |||||

| PD3 | 0.891 | |||||

| PD4 | 0.876 | |||||

| PD5 | 0.836 | |||||

| Life satisfaction | Life satisfaction | LS1 | 0.861 | 0.899 | 0.923 | 0.704 |

| LS2 | 0.811 | |||||

| LS3 | 0.860 | |||||

| LS4 | 0.835 | |||||

| LS5 | 0.828 | |||||

| Constructs | PD | PI | LS | SOC | NEI | ATTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 0.854 | |||||

| PI | 0.834 | 0.858 | ||||

| LS | 0.722 | 0.672 | 0.839 | |||

| SOC | 0.734 | 0.782 | 0.619 | 0.802 | ||

| NEI | 0.635 | 0.638 | 0.504 | 0.802 | 0.837 | |

| ATTR | 0.746 | 0.801 | 0.664 | 0.791 | 0.625 | 0.868 |

| Constructs | NC | PA | LS |

|---|---|---|---|

| NC | |||

| PA | 0.867 | ||

| LS | 0.695 | 0.783 |

| Constructs | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|

| PI | 0.701 | 0.506 |

| PD | 0.619 | 0.444 |

| LS | 0.560 | 0.384 |

| Hypothesis | Standard β | T Statistics | 95% Bias-Corrected Confidence Interval | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: NEI→LS | −0.035 | 0.462 | [−0.184, 0.108] | NO |

| H1b: SOC→LS | 0.071 | 0.792 | [−0.107, 0.249] | NO |

| H1c: ATTR→LS | 0.229 | 2.892 ** | [0.070, 0.376] | YES |

| H2a: NEI→PI | 0.043 | 0.758 | [−0.069, 0.153] | NO |

| H2b: NEI→PD | 0.140 | 2.153 * | [0.017, 0.275] | YES |

| H2c: SOC→PI | 0.361 | 5.173 *** | [0.219, 0.493] | YES |

| H2d: SOC→PD | 0.272 | 3.433 *** | [0.112, 0.422] | YES |

| H2e: ATTR→PI | 0.488 | 8.679 *** | [0.376, 0.598] | YES |

| H2f: ATTR→PD | 0.443 | 7.106 *** | [0.316, 0.563] | YES |

| H3a: PI→LS | 0.068 | 0.814 | [−0.095, 0.230] | NO |

| H3b: PD→LS | 0.465 | 5.293 *** | [0.294, 0.639] | YES |

| Relation of Path | The Point Estimate | T-Value | 95% Bias-Corrected Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEI→PI→LS | 0.003 | 0.401 | [−0.004, 0.029] |

| SOC→PI→LS | 0.024 | 0.792 | [−0.032, 0.089] |

| ATTR→PI→LS | 0.033 | 0.807 | [−0.047, 0.116] |

| NEI→PD→LS | 0.065 | 1.887 * | [0.009, 0.147] |

| SOC→PD→LS | 0.126 | 3.130 ** | [0.058, 0.220] |

| ATTR→PD→LS | 0.206 | 3.952 *** | [0.120, 0.321] |

| Place Attachment | Life Satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se | t | b | se | t | |

| constant | 0.441 | 0.110 | 4.014 *** | 0.778 | 0.136 | 5.733 *** |

| Neighborhood cohesion | 0.846 | 0.034 | 24,712 *** | 0.136 | 0.072 | 1.892 |

| Place attachment | 0.618 | 0.070 | 8.868 *** | |||

| R2 | 0.671 | 0.528 | ||||

| F | 610,691 | 166,874 | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Mediation Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.659 | 0.046 | 0.567 | 0.750 | |

| Direct effect | 0.136 | 0.072 | −0.005 | 0.278 | 20.637% |

| Indirect effect | 0.522 | 0.065 | 0.394 | 0.651 | 79.211% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Shen, X.; Xia, T. Mediating Power of Place Attachment for Urban Residents’ Well-Being in Community Cohesion. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156756

Liu T, Shen X, Xia T. Mediating Power of Place Attachment for Urban Residents’ Well-Being in Community Cohesion. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156756

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Tingting, Xiaoqi Shen, and Tiansheng Xia. 2025. "Mediating Power of Place Attachment for Urban Residents’ Well-Being in Community Cohesion" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156756

APA StyleLiu, T., Shen, X., & Xia, T. (2025). Mediating Power of Place Attachment for Urban Residents’ Well-Being in Community Cohesion. Sustainability, 17(15), 6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156756