1. Introduction

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) is a strategic approach that integrates technologies, processes, and people to manage and optimize interactions with current and potential customers [

1]. The main goal is to enhance customer satisfaction, loyalty, and lifetime value by delivering personalized and consistent experiences across all touchpoints [

2]. Effective implementation of CRM systems enables small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to derive meaningful insights into customer behavior and preferences. This data-driven approach enhances organizational responsiveness and strengthens competitiveness in rapidly changing market environments [

3].

The drastic changes in the competitive world in which companies operate have led to significant investments in CRM as one of the most successful strategies to improve organizational performance [

4,

5]. Organizations can benefit from digital technology to boost customer relationship performance because customer relationship performance is affected by the associated personalization [

6].

Companies have been investing in value creation strategies that focus on managing the relationship with their customers and integrating business networks and organizational processes [

7,

8] implementing CRM systems in order to properly manage the relationship with customers, integrating it into the company’s functions [

9,

10,

11].

CRM technologies have increasingly been recognized as a strategic priority for organizations aiming to enhance competitiveness [

2], constituting a fundamental element for the quality of customer service that constitutes one of the key points for many companies aiming to improve the experience offered to their customers [

12,

13,

14]. The aim is to improve customer satisfaction, loyalty and profitability [

15,

16] and, consequently, performance, innovation capacity and business success in a changing world, in the face of emerging challenges posed by growing digital complexity [

17].

The current approach to CRM systems as a business management tool seeks to establish channels and methods to manage customer-centric information [

18] to improve organizational performance [

19], discussing the presence of several moderators as conditioning factors for the greater or lesser impact of these systems on business performance [

12,

14,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

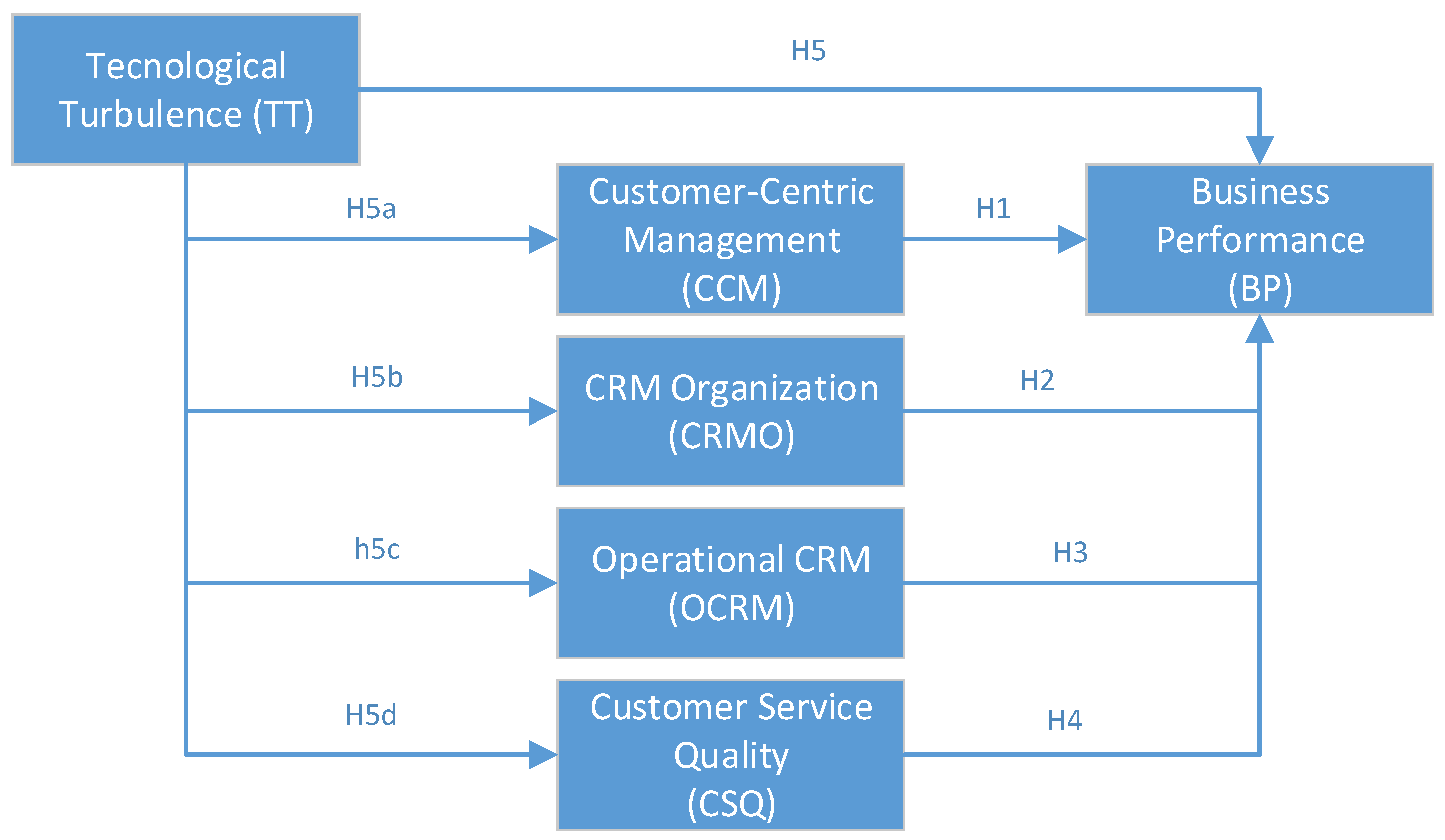

In Portugal, where micro, small and medium enterprises (SME) [

26] represent about 99.9% of the total companies [

27], studies on CRM adoption and its effects on business performance in Portuguese SMEs remain limited [

23], particularly when addressing dynamic external moderators such as technological turbulence. The aim of this study is to identify and test the factors that influence the impact of CRM technology on the business performance of Portuguese SMEs. This research adds to existing knowledge by proposing a model in which TT does not directly influence business performance, instead acting as a moderating factor, contradicting earlier suppositions [

24].

The article is structured as follows: first, we review previous works on the use of CRM technologies and their impact on business performance and present the conceptual framework and hypotheses. Next, in the research methodology, we describe the sample that served as the basis for the study, and how the data were collected and analyzed (including the validation of the questionnaire) and the SPSS v.30. and SmartPLS 4.0 software were used for the analysis. In the next, we present the data analyses and results of the study and discuss them considering previous academic research. Finally, we conclude the article by presenting the managerial, theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and future research directions.

5. Discussion

The results confirm that adoption of CRM systems has a positive impact on business performance. Among the hypotheses tested, technological turbulence (TT) showed no significant effect on business performance (BP), as indicated by the negative structural coefficient (−0.006).

CRM organization (CRMO) demonstrated a strong and significant influence on business performance (0.457), reinforcing the importance of internal alignment and structural support. This finding aligns with previous studies by Guerola-Navarro et al. [

20], Khlif [

34], Pozza et al. [

35], Silva [

23], Ullah et al. [

24], and Wang [

25], all of whom emphasized the role of CRM organizational structure. In contrast, this approach differs from Ullah et al. [

21], who posited that TT serves as a moderating factor. Research suggests that the significant impact of CRMO is associated with companies prioritizing leadership involvement, organizational unity, and interdepartmental teamwork, which in turn increases their chances of achieving tangible performance enhancements.

Customer-centric management (CCM), operational CRM (OCRM), and customer service quality (CSQ) demonstrated moderate yet significant effects on business performance. The findings confirm that several CRM elements make a significant contribution to performance results, in line with the assertions of Silva [

23], Wang [

25], and the research by Guerola-Navarro et al. [

20]. The success of a CRM system is contingent upon the proper execution of its constituent parts.

Rapp et al. [

36] further confirmed the positive though moderate, effect of CCM on performance, highlighting the importance of customer orientation in a strategic context. Similarly, Soltani et al. [

37] underlined the significance of internal factors, such as organizational capabilities and customer orientation, while also identifying customer knowledge management and IT usage as key contributors to CRM success.

The moderate influence of customer service quality (CSQ) is consistent with Elshaer et al. [

12], who identified service quality as a critical factor for business success. This conclusion is supported by Sharif and Sidi Lemine [

13] and Subagja et al. [

14], who found that high-quality customer service directly contributes to enhanced performance.

Despite initial expectations, technological turbulence (TT) showed no direct effect on business performance. This finding contrasts with previous research by Chatterjee et al. [

33], Silva [

23] and Ullah et al. [

24], who proposed technological turbulence (TT) as a moderator in the CRM–performance relationship. Chatterjee et al. [

33] suggested that technological turbulence (TT) could have a detrimental impact on operational sustainability, ultimately affecting the outcomes.

This study found that technological turbulence (TT) has a moderate influence on variables like customer-centric management (CCM) and CRM organization (CRMO) and a more pronounced effect on operational CRM (OCRM) and customer service quality (CSQ). The results of this study are consistent with previous research, specifically that of Guerola-Navarro et al. [

20], Pozza et al. [

35], and Wang [

25], which highlighted the connection between technological advancements and CRM capabilities.

These findings lead to the assumption that relational capabilities and other organizational factors can mitigate or act as intermediaries, thus allowing companies to maintain performance despite technological uncertainty [

32].

Although hypothesis H5 proposed a direct positive relationship between technological turbulence (TT) and business performance (BP), the statistical analysis did not find such an effect (−0.006). This suggests that technological turbulence (TT) does not directly enhance performance but rather affects it indirectly through the CRM components or under certain contextual circumstances. Research suggests that technological turbulence (TT) plays a significant role in enhancing CRM effectiveness, but it is not the primary cause of SME performance, contradicting the opinions expressed by Ullah et al. [

24] and Chatterjee et al. [

33].

The unsupported H5 is consistent with the evolving perspective that TT does not exert a uniform impact across all performance dimensions. Its role as an enabler may depend on mediating factors such as digital maturity or environmental context.

5.1. Managerial Implications

The findings of this research offer significant outcomes that can be utilized by company managers in their respective organizations. Managers can strategically use the impact of customer-centric management to implement customer management models, thereby increasing customer satisfaction and loyalty. Improving CRM (operational and organizational) is crucial in enhancing business performance, justifying investment in streamlining workflow, employee development and leveraging data analysis to foster better customer engagement and boost company expansion.

A well-rounded strategy that focuses on investing in innovative CRM technologies, particularly those leveraging AI, and effectively integrating them into employees’ workflows can enhance a company’s standing with its customers, boost brand reputation, foster customer loyalty, and ultimately drive business success. Research by Khneyzer et al. [

42] found that the use of AI-driven CRM systems has a substantial impact on streamlining customer interactions and aids in aligning business functions strategically within the digital transformation process.

Given that the conceptual model’s application was suitable for the Portuguese business environment, the adoption of CRM technology is anticipated to yield positive results, prompting other organizations to integrate CRM into their strategic development plans.

Companies benefit from implementing CRM systems as they enhance decision-making and streamline processes, ultimately contributing to the development of more sustainable practices. The use of CRM systems allows managers to implement strategies that optimize production, reduce excess and waste, and consequently enhance operational efficiency, leading to improved organizational performance and sustainability [

70,

71].

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study expands the field of CRM by combining dynamic capability theory with existing CRM performance models, demonstrating how technology transfer affects various CRM aspects to achieve agility and long-term market superiority for small to medium-sized enterprises.

This research offers fresh empirical findings through the examination of a conceptual framework within the sector of Portuguese small to medium-sized enterprises, an area where research on CRM adoption is relatively limited. Our research integrates organizational, operational, customer-focused, and service quality factors with the influence of technological upheaval, providing a more comprehensive and contextually relevant analysis that has not been presented in this specific combination previously.

The theoretical implications to be considered when studying the contribution of CRM to business performance allow us to consolidate the main factors that can affect this performance, namely, customer-centered management, operational CRM, and CRM organization, as proposed by other studies [

20,

23,

24,

25,

34,

35].

The results obtained also show that it is pertinent to consider the importance of moderating the effect of technological turbulence on business performance [

20,

25,

35]. Another important finding is the impact of customer service quality on business performance, which confirms the conclusions of other studies on CRM adoption [

12,

13,

14].

Recent studies also reinforce the role of CRM in supporting sustainable competitive advantages, particularly through social CRM practices that foster adaptability in SMEs, and highlight the strategic relevance of CRM tools in driving digital transformation and organizational alignment [

3].

The main success factors identified in the adoption of CRM by Portuguese companies demonstrate the validity of the model and provide a solid quantitative basis for future research in the context of a Portuguese SMEs.

5.3. Practical Implications

This research aims to offer businesses, regardless of whether they have a CRM system, a tool that enables them to access pertinent data for strategic decision-making within the context of their established policies by developing a conceptual framework and assessing the impact of the identified variables on business outcomes.

The outcome of the findings presented in this research, which in their context confirm many of the findings of previous research [

12,

13,

14,

20,

23,

24,

25,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] provide companies with relevant data that allows them to guide their future strategies, providing a basis for decision-making that allows them to monetize investments in CRM technologies and systems and thus increase business performance.

In addition to the direct gains in company performance, CRM systems, by centralizing and automating customer contact, make it possible to develop more effective digital marketing campaigns, reducing the need for paper, printing, and physical travel, thus making a significant contribution to sustainability [

72].

The managerial recommendations are summarized, by priority level, for each CRM dimension (

Table 8).

6. Conclusions

The results of this study emphasize the importance of implementing CRM systems and their significant positive effect on business performance. The organizational structure of CRM has a strong and positive impact on business performance. Operational CRM and customer service quality exert a moderate influence on business performance, whereas customer-centric management has a great relevance to business success, which corroborates research that highlights its relevance to business success.

While some studies, such as the one by Chatterjee et al. [

33], Silva [

23] and Ullah et al. [

24], have suggested that technological turbulence may moderate the relationship between CRM and performance, the current study found no evidence of this moderating effect. Although technological turbulence does not directly affect business performance, it moderately influences customer-centric management and the organizational structure of CRM and has a strong influence on operational CRM and the quality of customer service. This finding suggests that other moderating factors may mitigate the impact of technological turbulence on business performance. The presence of these moderating factors can reduce the negative effects of technological turbulence, allowing businesses to adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing environment.

These findings are consistent with recent contributions that associate social CRM practices with strategic adaptability in SMEs [

2] and recognize CRM systems as key enablers of digital transformation and integration across business functions [

3].

By identifying and understanding these moderating factors, businesses can develop strategies to leverage them and improve their overall performance.

Limitations and Future Directions of the Research

It is important to highlight that the population of this study is not known, that is, it is not possible to determine whether the sample is representative. With regard to the characterization of the sample, it is important to note that it is balanced between genders; however, it is important to note that most respondents are between 30 and 49 years old, have higher education qualifications, and occupy middle management positions. The size of the company where most respondents work is included in the group of small and medium-sized enterprises. This information is based on the number of employees, which is the indicator recommended in the context of the European Union [

26].

Given the sample’s concentration in central Portugal, regional dynamics may limit the generalizability of the findings. Differences between urban and rural SME environments—especially in digital maturity—should be considered, and broader geographical replication is encouraged for future studies. Future research could adopt longitudinal or mixed-method approaches to examine CRM system evolution and long-term performance impact.

It may also be interesting to investigate companies with different levels of experience and/or those who are at different stages of using the system, thus verifying the need for future studies that investigate these aspects. Different activities across different departments and positions offer different perspectives that can change the outcomes.

Finally, a possibility of continuing the research work would be to apply the model proposed in this research to several companies of different sizes (small, medium and large) which use CRM systems to evaluate whether the improvements in business performance are identical, or different, according to the characteristics of the company.