1. Introduction

As a leading energy nation, China’s low-carbon transformation of energy is not only crucial for achieving its dual-carbon objectives but also an essential pathway to sustainable development. Its transformation experience will provide a new paradigm for developing countries [

1,

2]. At present, China’s energy transition features two primary approaches: increasing renewable energy utilization and improving the clean and efficient use of fossil fuels [

3,

4,

5]. These approaches have crystallized into three policy archetypes: direct government regulation (setting emission standard or imposing target constraints), Pigouvian measures (primarily taxation and subsidies), and Coasean mechanisms (centered on emissions trading), constituting an integrated policy matrix for energy transition [

6,

7]. Given the availability of diverse energy policy tools, the determination of policy priorities and the selection of preferred policy tools by local governments in low-carbon energy transition practices constitutes a critical factor influencing transition performance.

As the primary entities governing local public affairs, local governments exhibit differentiated priority preferences in the process of policy implementation [

8,

9]. In response to policies issued by higher-level governments, local governments base their decisions on various considerations and assign different rankings to existing policies [

10]. Under the objective constraints of limited organizational resources, policies with different rankings receive varying levels of financial and personnel allocation. Policies that rank highly typically secure many resources and are prioritized for execution, whereas those with a low rank may be implemented perfunctorily or not at all [

11,

12]. Therefore, as one of the common selective governance behaviors of local governments, their prioritization of different policies significantly impacts the effectiveness of local governance [

13]. Clarifying the primary logic behind local governments’ prioritization of energy policies is of great significance for optimizing the behaviors of local governments and promoting the process of low-carbon energy transformation.

Government attention allocation serves as a critical lens for understanding local governments’ policy prioritization behaviors. Policy prioritization essentially refers to the determination of a sequence of actions and is a process wherein local governments and their functional departments allocate competitive attention to the various policy tools provided by higher-level governments [

14]. As attention reflects decision-makers’ constrained judgments about “what matters more”, it constitutes a fundamentally scarce resource. Consequently, local governments’ attention distribution across different policies typically exhibits a zero-sum characteristic [

15,

16]. When a policy tool captures governmental attention, it becomes a priority—garnering substantial political resources and expedited implementation. Conversely, policies failing to secure attention risk deferred, perfunctory, or null execution [

17,

18].

How can we understand the logic of government attention allocation? Existing research primarily adopts three perspectives: organizational structure, actor characteristics, and policy attributes. The organizational structure perspective emphasizes the influence of the government organizational structure and institutional frameworks on attention allocation. It suggests that under a pressure-driven system, higher-level governments employ quantitative assessments, promotion incentives, and reward–punishment mechanisms to influence local governments’ attention allocation [

19,

20,

21,

22]. As a result, local governments’ attention and prioritization of governance issues tend to align closely with those of higher-level governments, exhibiting a degree of path dependency and self-reinforcement [

23,

24]. Additionally, in the context of interregional competition, local governments often imitate the policy actions of neighboring regions, which reflects a pattern of “vertical adaptation and horizontal absorption” in attention allocation [

25]. The actor characteristics perspective highlights the agency of decision-making participants. It posits that officials’ risk preferences or decision-making styles, the government’s organizational interests, and external pressures from direct or indirect stakeholders are the primary factors influencing local government attention allocation [

26,

27]. When policy actions yield greater benefits or when external pressure from interest groups intensifies, local governments are more likely to concentrate their attention [

28]. According to the policy attributes perspective, policies that are easily measurable, low in conflict, and high in risk are more likely to capture government attention [

29,

30,

31]. Conversely, policies lacking quantifiable indicators or with high input costs, relatively low advantages, or high positive spillover effects often receive insufficient attention [

32,

33]. Furthermore, local economic, financial, and institutional resources play a moderating role in the relationship between policy attributes and government attention [

34].

Existing studies have provided insights into local governments’ energy policy prioritization behavior from organizational, individual, and policy dimensions, yet gaps remain for further exploration. The literature has the following gaps. (1) It fails to explain why policy prioritization differs among local governments with similar organizational structures. Currently, China’s low-carbon energy transition exhibits weak incentives and constraints—it neither directly contributes to officials’ political advancement nor has clear accountability cases emerged. China’s current energy transition practices, particularly in low-carbon cities and carbon peaking pilot programs, reveal a lack of clear policy targets or corresponding support—financial or otherwise—from higher levels of government. As a result, local governments operate in an environment of weak incentives and weak constraints for low-carbon initiatives [

35]. Moreover, local governments at the same administrative level within a jurisdiction share identical institutional environments for energy transition, making structural perspectives inadequate for explaining its policy logic. (2) It overlooks inter-actor interactions. Policy choices for low-carbon energy transition affect the distribution of interests across various entities, including governments at different levels and enterprises. In other words, local governments’ policy prioritization is not shaped solely by pressure from a single type of stakeholder but is embedded within complex internal and external governmental relations. As interactions among different stakeholders vary, so too does the government’s prioritization of “whose interests to protect first”, leading to corresponding shifts in policy sequencing. (3) It cannot clarify why policy sequencing differs despite identical policy tools and attributes. While policy attribute research reveals general attention allocation patterns, it seldom addresses variations in local attention distribution. An overview of government attention allocation theories reveals that the three levels—organizational, individual, and policy—are not entirely isolated. The allocation of government attention is a subjective choice shaped by objective contexts, and no single level alone provides a complete explanation. Adopting a systemic perspective to examine the interactions among these levels thus emerges as a viable approach to understanding government attention allocation [

36]. This study therefore integrates individual and policy dimensions to construct an explanatory framework addressing government internal–external relations and policy tool attributes. Taking the energy policy choices of CGs in Hangzhou’s carbon peaking pilot program as a case study, we employ comparative case analysis and a DCE to address the question: How do government internal–external relations and policy attributes influence local governments’ policy prioritization? The findings aim to provide insights for replicating grassroots governments’ low-carbon energy transition practices in China. It should be noted here that the phenomenon of policy prioritization is particularly prevalent among CGs, the lowest level of government with a complete organizational structure. On the one hand, CGs occupy a critical position in China’s administrative hierarchy, serving as intermediaries that connect higher and lower levels of government, facilitate communication across vertical and horizontal lines, and coordinate various sectors [

37]. However, this comprehensive role assignment is misaligned with the actual administrative authority, fiscal resources, and public resources available to these governments. CGs face inherent contradictions, such as limited fiscal authority, extensive administrative responsibilities, and a heavy workload, a situation that necessitates the allocation of varying levels of attention to different policies. On the other hand, positioned at the bottom of the administrative hierarchy, CGs operate within a relatively limited scope of supervision from higher levels of government. Coupled with information asymmetry, this grants them significant autonomy in their policy implementation and decision-making processes. Regarding the choice of Hangzhou’s carbon peaking pilot program as a case study, in alignment with the Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030, and to explore diverse pathways for achieving carbon peaking in different cities and industrial parks, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) selected 100 representative cities and parks nationwide in October 2023 to initiate pilot programs for carbon peaking. The National Carbon Peaking Pilot Construction Plan was subsequently issued to guide these initiatives. This plan identifies the promotion of green and low-carbon energy transition as the primary task for pilot cities and emphasizes the need to “determine a reasonable pathway for energy transition based on local energy endowments while ensuring energy supply security”. Additionally, the plan provides reference indicators for the green and low-carbon energy transition in pilot cities, including the proportion of nonfossil energy consumption and the share of electricity in final energy use.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

The attributes of policy tools refer to the inherent characteristics and features of the tools themselves [

38]. The attributes of policy tools, as crucial means for achieving policy objectives, reveal the differences among them, determine their modes of action and expected outcomes, and significantly influence government behavioral choices and the policy development process [

30,

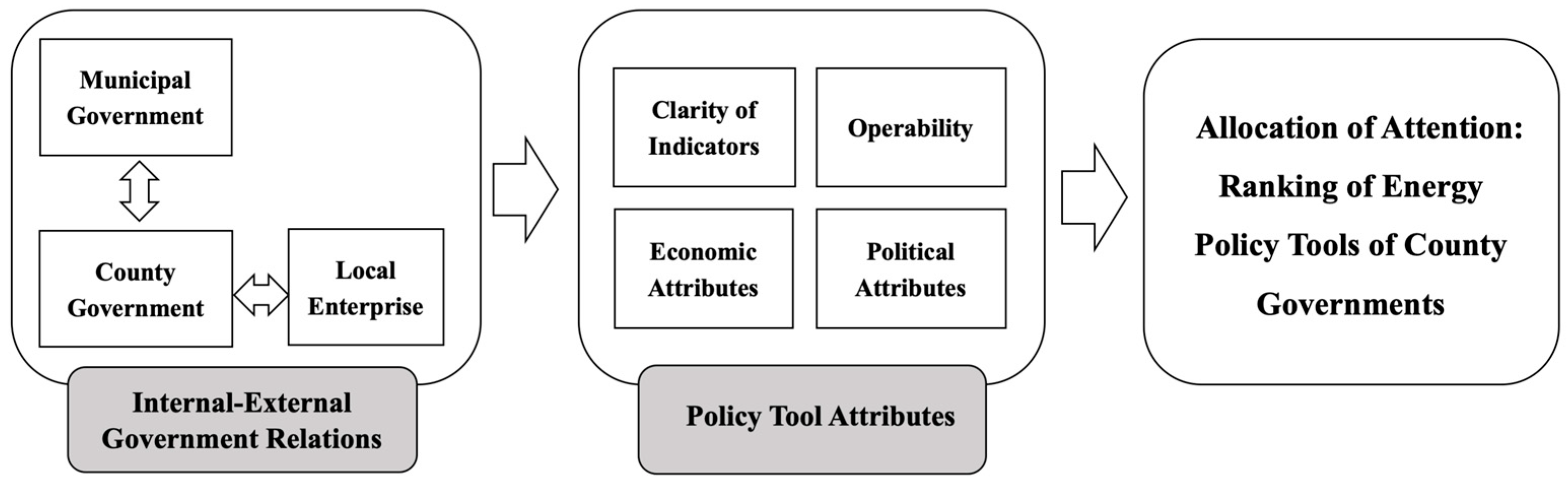

39]. Generally, the same policy tools possess consistent attributes, and the priority rankings of these tools by CGs should logically converge on the basis of these attributes. However, the local differentiation of the prioritization of policy tools stems from the fact that CGs develop varying attribute preferences under different internal–external governmental relations. Therefore, we establish an analytical framework from the perspectives of internal–external government relations and the attributes of policy tools. Among these, the attributes of policy tools serve as the primary criterion for the selection of energy policy tools by CGs. Governments form different preferences for policy tool attributes on the basis of variations in internal–external relations, which ultimately leads to different priorities for energy policies (

Figure 1).

2.1. Attributes and Priorities of Policy Tools

Public policy tools possess diverse attributes, such as synergy, operability, goal orientation, and cost effectiveness. Drawing on existing research [

32,

40,

41] and the practical selection of policy tools by CGs, we focus on the indicator clarity, operability, economic characteristics, and political characteristics of policy tools.

Policy formulation is premised on the achievement of economic, political, or social benefits. Clear policy objectives help local governments concentrate on policy issues and enhance the actual performance of policy tools. Conversely, ambiguous policies often require additional implementation costs and provide leeway for subordinate governments to adapt or passively implement policies [

30,

42]. Therefore, local governments in China tend to prefer policies with a high degree of clarity. Local governments also allocate more attention to policies that include quantifiable indicators [

32].

The operability of policy tools pertains to the ability of local governments to effectively implement policies, which directly influences the ease of policy execution. Policy tools with high operability incur low transaction costs during implementation and are likely to yield high policy performance [

40]. Additionally, highly operable policy tools are typically aligned with real policy contexts, possess clear operational boundaries, and help mitigate potential issues during implementation, thereby reducing policy risk. Thus, given similar attributes, policy tools with strong operability are likely to be prioritized by local governments.

Low-carbon energy transformation embodies both economic and political characteristics, and energy policy tools inherently include economic and political attributes. The economic attributes focus on whether the implementation of policy tools impacts local enterprises. Local governments that prioritize economic considerations often aim to protect the interests of local enterprises and maintain GDP growth and thus prefer policy tools with strong economic attributes (those with minimal impact on enterprise production). The political attribute aspect emphasizes whether the implementation of policy tools supports political achievements or attracts attention from higher-level governments. Local governments that prioritize political considerations often seek to “create highlights” and favor policy tools with strong political attributes (those likely to attract attention from higher-level governments). Generally, to gain recognition or other policy support from higher-level governments, local governments pay close attention to political attributes. However, to mitigate the impact of energy transformation on local economic development, their attention allocation tends to favor economic attributes, and they prioritize policy tools with strong economic attributes [

41].

2.2. Preferences in Internal–External Government Relations and Policy Tools

Public policy represents a reallocation of social values, and the selection and implementation process of public policies is essentially a process of interest selection and game-playing among government entities [

43,

44]. Within the context of principal–agent theory, CGs exhibit multiple interest orientations, encompassing political and economic interests. Their choice of policy tools must reflect various factors, including the demands of higher-level governments, the realization of their own interests, and the development of local enterprises [

45]. Owing to the unique nature of low-carbon transformation, conflicts have arisen among CGs in pursuit of different interests. Determining which interests to prioritize and whose interests to protect first has become a central debate in the ranking of policy tools. From the perspective of the selection process of energy policy tools, the prioritization of these tools is the result of games among relevant stakeholders. Intergovernmental relations and government–enterprise relations have emerged as crucial factors influencing the prioritization of policy tools.

From the perspective of intergovernmental relations, higher-level governments can influence the selection of policy tools by subordinate governments through their authority. Under the unique hierarchical governance structure in China, decision-making power is concentrated upwards, with higher-level governments holding the dominant role in policy formulation, whereas subordinate governments often act as “subordinate executors” who follow orders and make policy adaptations or choices within limited policy spaces [

46,

47]. Higher-level governments not only transmit policy objectives and interest demands downwards through their authoritative pressure but also provide support for the policy implementation of subordinate governments, thereby influencing their policy selection behaviors to a certain extent. When higher-level governments are relatively strong, they can guide subordinate governments to allocate attention to certain areas and to prioritize certain policies emphasized by the higher-level governments through mechanisms such as accountability and promotion [

25,

48]. Conversely, when higher-level governments are weak, subordinate governments are inclined to focus on enterprise interests or make policy tool selections on the basis of their own interests and needs.

From the perspective of government–enterprise relations, local enterprises, as direct stakeholders in the low-carbon transformation process at the local level, have opportunities to influence the prioritization of policy tools by CGs by exerting external pressure [

28]. The extent of an enterprise’s influence is closely related to its scale. The demands of leading local enterprises, as major contributors to local GDP and important sources of fiscal revenue for local governments, become a critical consideration for local governments. Under the promotion tournament system centered on GDP, local governments and enterprises share convergent interests, which creates incentives for local governments to prioritize certain policies to safeguard enterprise interests. In contrast, small enterprises often lose their voice in the game with the government, and local governments are prone to overlooking the demands of these enterprises and instead prioritizing their own interests or the interests of other stakeholders.

In this paper, we collectively refer to the relationships between vertical levels of government and those between local governments and enterprises as internal–external government relations. In the initial phase of low-carbon energy transformation, conflicts of interest exist between higher-level governments and local enterprises. Therefore, in the internal–external relations of CGs, one relationship often dominates while the other remains secondary, and the dominant relationship typically becomes the priority interest protected in the selection of policy tools. The influence of internal–external government relations on policy tool selection manifests primarily through the altered preferences of CGs regarding the attributes of policy tools, which ultimately affects their prioritization. In the context of the low-carbon energy transition, when local energy-intensive enterprises are small scale and exert weak external pressure, vertical intergovernmental relations dominate. In such cases, the selection of policy tools by CGs is guided by the low-carbon governance demands of municipal governments (MGs), and CGs focus on attributes that facilitate task completion, such as the clarity of indicators and political significance, with the aim to gain recognition from MGs by efficiently completing the transformation tasks and thereby securing additional policy or financial support. Conversely, when local energy-intensive enterprises are large in scale and exert significant external pressure on the government, government–enterprise relations dominate. In such scenarios, the selection of policy tools is driven by enterprise interests, with emphasis on the operability and economic attributes related to governance costs and with the goal of minimizing the impact of energy policies on enterprise production and operations while sustaining local economic development. On this basis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Under different internal–external government relations, CGs focus on different attributes of policy tools and thereby prioritize different energy policy tools.

Hypothesis 1.1: CGs dominated by intergovernmental relations prioritize policy tools on the basis of higher-level task orientation and political demonstration effects and emphasize the clarity of indicators and political attributes in the selection of energy policy tools.

Hypothesis 1.2: CGs dominated by government–enterprise relations prioritize policy tools on the basis of enterprise interests and economic growth effects and focus on the operability and economic attributes in the selection of energy policy tools.

Given that county-level governments rarely issue formal energy policy texts, which makes it difficult to directly determine the prioritization of different policy tools, in this study, we first employ a case comparison analysis to verify the above research hypotheses. We begin by describing the background of the low-carbon energy transition in two typical counties and presenting the fundamental process of energy policy tool prioritization. We then deconstruct the policy tool prioritization logic in these two cases on the basis of the theoretical framework to preliminarily test the research hypotheses. A DCE is subsequently adopted to validate the preferences of CGs for different attributes of energy policy tools under varying internal–external government relations.

3. Case Comparison: County A and County B in Hangzhou

As one of the pilot cities for achieving carbon peaking, Hangzhou has made remarkable achievements in the low-carbon transformation of energy. In May 2024, Hangzhou formulated the National Carbon Peaking Pilot (Hangzhou) Implementation Plan (hereinafter referred to as the Plan). The Plan identifies low-carbon energy transition as one of the ten major tasks of Hangzhou’s carbon peaking pilot initiative. It outlines specific actions for the transition from five perspectives: accelerating renewable energy development, promoting efficient fossil energy use in enterprises, expediting the deployment and application of hydrogen energy, expanding the scale of external green electricity, and accelerating the construction of a new power system. These actions primarily involve the use of policy tools such as photovoltaic subsidies, the phasing out of outdated production capacity, planning (hydrogen energy), green certificate/electricity trading, and infrastructure development (energy storage) (

Appendix A).

Given the large number of counties under Hangzhou’s jurisdiction, we adhere to the principle of theoretical sampling in case selection [

49] and ultimately identify County A and County B as the research subjects. Both counties are under the jurisdiction of Hangzhou (and not in the main urban area), and they share similar institutional environments and policy toolkits in the context of the carbon peaking pilot. However, the two counties present notable differences in the prioritization of low-carbon energy transition policy tools, which provides an opportunity for comparative case analysis. Additionally, we carefully consider the representativeness of the cases. Both Counties A and B were previously classified as high-energy-consuming regions in Hangzhou and needed a low-carbon energy transition. The key difference lies in the fact that County A underwent significant industrial restructuring earlier than County B, which resulted in reduced pressure for a low-carbon energy transition at the current stage, whereas County B is still in a critical phase of its low-carbon energy transition and faces considerable pressure. Their respective policy prioritizations reflect the general logic of policy tool selection by county-level governments under varying transition pressures.

The data in this study were collected from semi-structured interviews, secondary sources, and other channels. The primary data collection consisted of three main stages. In the first stage, we conducted field research on the energy industry development in Districts A and B to gain a preliminary understanding of the low-carbon energy transition context in these two counties. The second stage involved three rounds of semi-structured interviews: after the release of the Plan, we conducted an in-depth interview with Mr. Z, the official in charge of low-carbon energy transition policies at the Hangzhou Development and Reform Commission, to explore the background of municipal-level policy formulation, the core content of the policy, and the practical challenges faced by the two districts. Following the formal implementation of the Plan, we visited the development and reform bureaus of Districts A and B and conducted semi-structured interviews with the heads of their energy departments, Mr. H and Mr. L, respectively. These interviews focused on the districts’ assessments of the importance of different low-carbon policy tools and their evaluation criteria. In the third stage, follow-up interviews were conducted via WeChat and phone calls with the three aforementioned respondents to supplement and refine the previous discussions. Additional materials, including policy documents, county-level emissions reduction data, and corporate revenue data related to low-carbon energy transition, were also obtained. To increase the reliability of the data, we extensively collected secondary data to corroborate the findings. These data sources include annual statistical bulletins, monthly statistical reports, statistical yearbooks, and final fiscal account reports obtained from the official websites of county statistics bureaus and finance bureaus, as well as relevant commentary and reports from authoritative media outlets, such as Sohu, The Paper, and China News Service.

3.1. County A: Task-Oriented Policy Tool Prioritization Under Low Pressure

Located upstream of the Qiantang River, County A was historically dominated by high-pollution and high-energy-consuming industries, such as papermaking, smelting, and chemical manufacturing. Owing to severe downstream water pollution (affecting central Hangzhou) and limited success from six prior rounds of rectification, County A adopted the “Squat Down, Jump Up” strategy in late 2016. This strategy focused on relocating enterprises, shutting down thermal power plants, and attracting new industries to facilitate regional energy structure transformation. During this process, County A invested heavily in the closing of more than 1000 papermaking enterprises, nearly all copper smelting plants, and more than 50 chemical factories. The entire remediation work was based on high standard compensation, and the withdrawal cost of the paper industry alone was nearly CNY 58 billion. Following these efforts, the regional energy demand significantly decreased, leading to the shutdown of four thermal power plants. Coal consumption decreased sharply from 5.99 million tons to 670,000 tons, and the energy intensity per unit of GDP decreased from 2.5 tons of standard coal per CNY 10,000 to 0.5 tons, exceeding the national 13th Five-Year Plan target of a 21% reduction and contributing substantially to Hangzhou’s energy efficiency goals. After eliminating its “black GDP” based on high-pollution and energy-intensive industries, County A actively introduced emerging industries, such as high-tech manufacturing, and maintained a low number and a small scale of energy-intensive enterprises. Overall, following this extensive industrial restructuring, County A faces minimal external pressure from enterprises and higher-level governments during the transformation. However, due to significant economic investments and incomplete industrial restructuring, its GDP growth and fiscal performance remain relatively weak.

In selecting energy transition policy tools, County A prioritizes photovoltaic subsidies, infrastructure development (energy storage), and green electricity/certificate trading, and it relegates policies on phasing out outdated production capacity and planning (hydrogen energy) to a secondary position (

Table 1). Photovoltaic subsidies are emphasized due to municipal government-mandated annual installation targets and the reduced costs and short payback periods for these enterprises, which enhance policy feasibility. Additionally, the closure of thermal power plants necessitates alternative energy sources for industrial and residential needs, and County A’s mountainous terrain is well suited to photovoltaic development. Infrastructure development (energy storage) is prioritized to address the instability of the renewable energy supply and align with higher-level policy requirements, although its strategic importance outweighs its practical utility. Most current energy storage projects are implemented through public–private partnerships, leveraging the county’s efforts to attract new enterprises. Green electricity/certificate trading is prioritized because Hangzhou allocates trading quotas on the basis of fossil energy consumption and total energy use. County A faces minimal pressure to meet these quotas because of its low energy consumption after the relocation of high-energy-consuming industries. Furthermore, the CG can negotiate with enterprises to encourage certificate purchases. Phasing out outdated production capacity is deprioritized, as boiler elimination targets have been largely achieved, which leaves limited room for further progress. Planning (hydrogen energy) is deferred because of the lack of clear performance indicators, immature technology, and high initial government investment costs. However, recognizing hydrogen’s potential as a “highlight” in low-carbon governance, County A actively supports hydrogen-related enterprises and constructs hydrogen refueling stations.

3.2. County B: Corporate Interest-Oriented Policy Tool Prioritization Under High Pressure

County B, located in the eastern part of Hangzhou, is dominated by manufacturing industries, such as automobile production, mechanical equipment, and textiles and apparel. The regional GDP consistently ranks among the highest in Hangzhou’s counties. Given its manufacturing-heavy industrial structure, County B also ranks highly in energy consumption per unit of GDP and is characterized by energy-intensive and high-consumption industries. In 2023, the total annual energy consumption in County B still reached 10.8 million tons of standard coal. The key energy-intensive sectors include textiles and chemical fiber manufacturing, which account for approximately 67% of the total energy consumption of the region’s large-scale industries. The energy consumption per unit of value added in these sectors ranges from 1.7 to 2.2 tons of standard coal per CNY 10,000, more than double the average for large-scale industries. Moreover, these industries feature a large number of enterprises, widespread distribution, and significant scale, with two companies generating annual revenues exceeding CNY 400 billion and consistently ranking among the Fortune Global 500. These companies are vital contributors to County B’s fiscal revenue. Overall, owing to its industrial structure, County B faces the dual challenges of significant external pressure from high-energy-consuming enterprises and the burden of meeting stringent energy-saving and emissions reduction targets set by higher authorities under the carbon peaking pilot.

In selecting policy tools for the energy transition, County B prioritizes photovoltaic subsidies, the phasing out of outdated production capacity and green electricity/certificate trading, while it rarely addresses infrastructure development (energy storage) and planning (hydrogen energy) (

Table 2). The focus on photovoltaic subsidies is due to the policy’s maturity, high acceptability among enterprises, and strong feasibility. Additionally, given the substantial difficulties associated with industrial restructuring, the promotion of photovoltaic construction helps increase the regional electricity supply, control total energy consumption, and reduce energy-saving costs for enterprises and thereby achieves the dual control of energy consumption. The elimination of outdated production capacity is prioritized as the most direct approach to reducing energy consumption in the context of high energy use and emissions. Coupled with mandates from higher authorities and central inspections, County B must emphasize tasks such as phasing out small boilers as part of its energy transition. However, this policy tool ranks slightly lower than that of photovoltaic subsidies because some high-energy-consuming enterprises are currently relocating, which reduces the demand for heat supply, diminishes the willingness to upgrade thermal power plant equipment, and thereby increases policy resistance. Green electricity/certificate trading is prioritized because of the annual quota of 600,000 green certificates set by the MG. While the policy lacks sufficient political and legal support, which makes quota fulfilment a challenge for County B, green certificates can offset a certain amount of energy consumption. Compared with mandatory energy-saving measures, the promotion of enterprises’ purchase of green certificates reduces the impact on production in the current economic downturn. County B adopts a neutral stance on infrastructure development (energy storage), neither supporting nor opposing it, due to the policy’s unclear objectives, potential energy losses, and safety concerns. Most importantly, energy storage infrastructure does not directly contribute to emissions reduction and thus offers little relief to low-carbon governance pressure. County B is even more conservative in its approach to planning (hydrogen energy), primarily because the local industrial chain lacks related enterprises and the technology remains immature. The support of enterprises with such investments could adversely impact their long-term development.

3.3. Comparative Case Analysis: Internal–External Government Relations and Policy Tool Attributes

Through case analysis, it is evident that both Counties A and B prioritize policy tool attributes such as the presence of clear targets, operational feasibility, impact on enterprise production, and the ability to attract higher-level government attention in their selection of energy transition policy tools. However, the emphasis on these attributes varies between the two regions. Overall, County A focuses more on the fulfilment of tasks assigned by higher authorities, whereas County B places greater emphasis on the impact of policy tools on enterprise interests. This divergence in priorities is directly linked to the internal–external government relations faced by each region.

From the perspective of County A, following the large-scale relocation of the papermaking, smelting, and chemical industries, only seven or eight small-scale papermaking enterprises and a limited number of chemical enterprises remain in the region. Consequently, energy demand has significantly decreased, and high-energy-consuming enterprises are characterized by their small number and scale and thus exert minimal external pressure on government low-carbon decision-making. As shown by the declining growth rate of total industrial profits and taxes (

Table 3), County A’s reliance on large-scale manufacturing industries has been decreasing. Additionally, due to industrial restructuring, the government has faced increasing fiscal imbalances and a declining fiscal self-sufficiency rate. To address fiscal deficits and promote local industrial restructuring, County A has multiple aims, including seeking higher-level government attention, securing financial support, and obtaining other policy incentives. In summary, the vertical relations between the MG and the CG dominate County A’s governmental relations, which leads the CG to prioritize policy tool attributes such as whether MGs set targets, the difficulty of target completion, and whether the execution of policy tools can create “highlight achievements”. This is corroborated by the interviews conducted in County A. For instance, although infrastructure development (energy storage) is highly operational, its objectives are relatively vague, and it currently generates limited economic benefits while posing safety risks, such as fire hazards. Unlike County B, which adopts an indifferent stance, County A prioritizes this policy tool, not only for its critical role in ensuring energy supply but also because infrastructure development is a key means for CGs to demonstrate policy achievements. Projects such as virtual power plants send signals to MGs about active engagement in energy transformation.

In contrast, County B has a high fiscal self-sufficiency rate, with limited reliance on municipal fiscal transfers and a low inclination to seek higher-level government attention. Moreover, influenced by its industrial structure, County B hosts many high-energy-consuming enterprises, which are major contributors to regional fiscal revenue. The development needs and opinions of these enterprises significantly influence the government’s policy tool selection. Furthermore, within the existing industrial framework, County B serves as a primary source of tax revenue for Hangzhou and plays a leading role in overall economic development. To mitigate the economic impact of the energy transition on County B, Hangzhou’s assessment criteria for the region are relatively lenient, with the MG retaining centralized control over quota allocation. Consequently, County B’s government places less emphasis on responding to higher-level low-carbon mandates and instead prioritizes the production needs and development requirements of high-energy-consuming enterprises. Overall, compared with the vertical relationship between the MG and the CG, the relationship between the CG and high-energy-consuming enterprises is pivotal in County B’s governmental relations. As a result, County B focuses more on the economic attributes of policy tools and prioritizes those that minimally impact enterprise production or enhance enterprise benefits. The interviews in County B reveal that photovoltaic subsidies and green electricity/certificate trading policies are prioritized not only because of their clear targets and operational feasibility but also because they can reduce or offset energy consumption quotas and alleviate the direct pressure on local enterprises to conserve energy and reduce emissions. Additionally, the inclusion of outdated capacity elimination as a priority is partly motivated by its long-term benefits for energy enterprises through the removal of low-efficiency boiler equipment.

5. Discussion

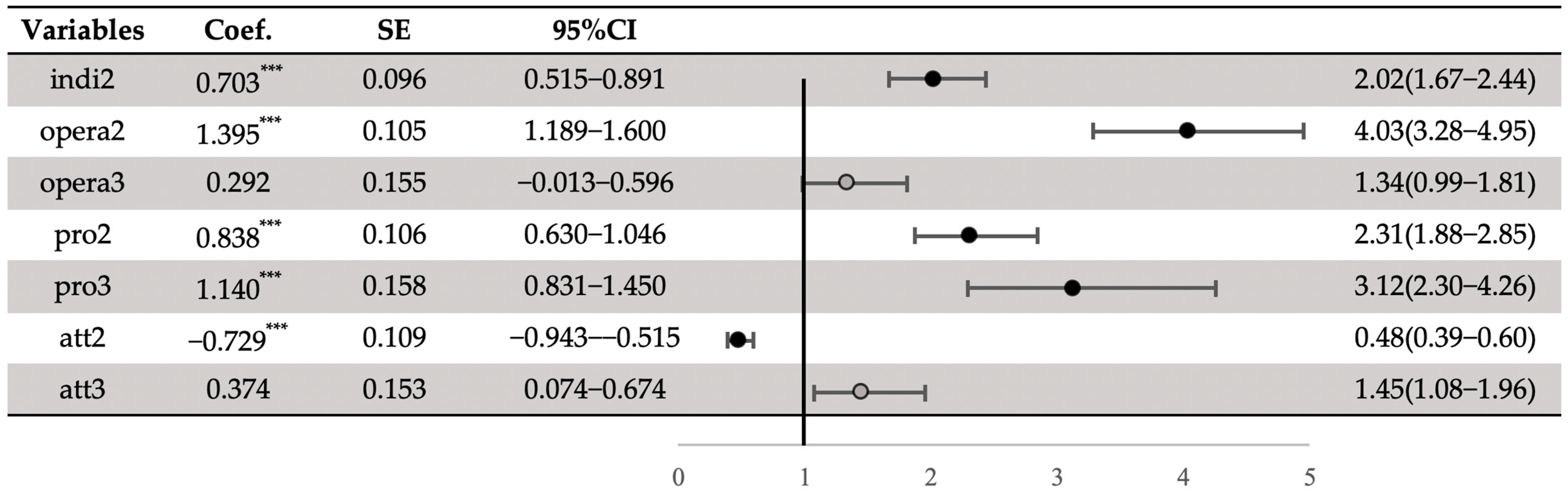

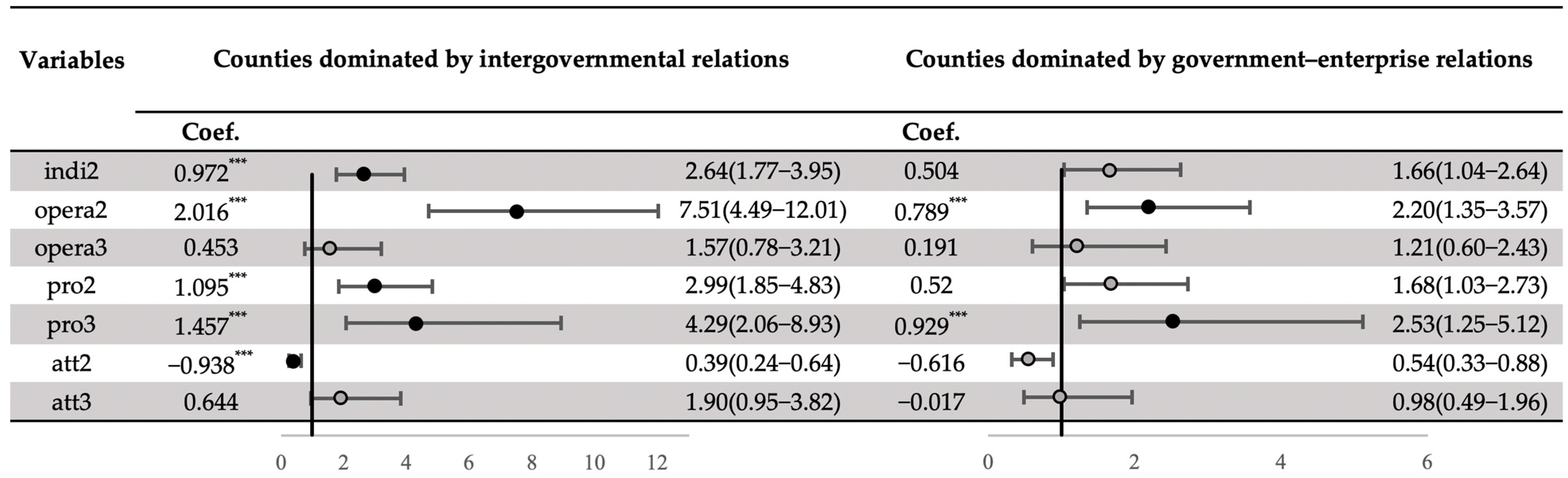

Contrary to the prevailing literature’s assumption of homogeneous policy attribute preferences among local governments [

40,

59], this study, through examining low-carbon energy policy selections across CGs in Hangzhou, reveals that variations in government internal–external relations can reshape their inherent preferences for policy tool attributes. The findings demonstrate significant differences in local governments’ preference for policy tool attributes under distinct internal–external relational contexts. On the one hand, counties dominated by intergovernmental relations consider not only the clarity of indicators and political attributes but also the operability and economic attributes of policy tools. This is because these counties aim to meet regional transformation targets and gain higher-level government recognition, which requires the achievement of assigned tasks, especially in the context of a carbon peak pilot. Therefore, in addition to considering whether higher-level governments set specific indicators, these governments assess the difficulty of achieving the targets and favor policies with clear and attainable indicators. Additionally, the consideration of economic attributes is tied to China’s fiscal decentralization system. Low-carbon energy transformation is just one aspect of local governance; in a promotion system centered on GDP growth, local economic development is also a critical factor. Thus, during the transformation process, CGs cannot focus solely on targets and ignore local enterprise development and economic growth; this reflects a logic consistent with that of existing studies that advocate balancing political and economic incentives [

60]. On the other hand, counties dominated by government–enterprise relations prioritize the economic attributes and operability of policy tools, as the development demands of enterprises under economic pressure take precedence, and these counties aim to minimize the impact of energy policies on businesses. These counties typically face high energy consumption and significant enterprise emission reduction pressures, such that mandatory measures are detrimental to both short-term enterprise interests and local GDP growth. Fortunately, the higher-level government has provided a comprehensive set of policy tools for low-carbon energy transition, which creates operational flexibility for CGs in policy selection. By prioritizing policies that minimally affect enterprise production or demonstrate certain operational feasibility, CGs can achieve the objective of a “rescue curve” approach. The higher-level government, seeking to maintain steady GDP growth, often tacitly permits such practices and adjusts allocation targets within jurisdictions to ultimately fulfill objectives set by even higher authorities. Moreover, CGs emphasize tool feasibility because highly operable policies are more effective in motivating participation from energy-intensive enterprises and other stakeholders. The combination of these two attributes helps reduce political costs while amplifying policy economic benefits. The conditional logit model results further indicate that CGs tend to favor moderately operable tools because highly operable tools, while easy to implement, may not sufficiently demonstrate efforts to higher authorities, whereas low-operability tools involve high costs. Thus, moderately operable tools that balance performance and cost become the preferred choice.

It should be emphasized that the selection logic of CGs in choosing energy policy tools—based on government internal–external relations and policy tool attributes—is closely tied to China’s institutional context of low-carbon energy transition, and to some extent differs from the selection approaches in other countries and other public policy domains. On the one hand, local governments’ policy behaviors are embedded within the national political–economic system, leading to distinct priorities regarding policy tool attributes. For instance, in the U.S., where local governments enjoy greater autonomy and independent legislative power, energy transition policies diverge across federal, state, and local levels, with local governments rarely factoring in political considerations but prioritizing economic efficiency [

61]. Under a multi-party competitive system, Germany’s low-carbon energy policies place greater emphasis on responding to voters’ environmental demands [

62]. Meanwhile, in Australia, where energy resources are abundant, low-carbon policy choices are often captured by the interests of “elite groups” [

63]. On the other hand, China’s low-carbon task currently presents weak incentives and constraints, and the lack of mechanisms reduces its importance in local governance, which leads to its neglect in policy tool selection. Compared with the emphasis on quantifiable indicators in general government actions [

48], “clear indicators” or “higher-level government attention” are not highly prioritized in the energy policy tool selection of CGs, with counties dominated by government–enterprise relations often disregarding these factors. Conversely, the experimental data show that, during the overall economic downturn, CGs highly prioritize economic attributes and operability, with even counties dominated by intergovernmental relations showing significant concern for economic attributes in energy policy tool selection. This reflects both concerns over the impact of energy transformation on local economic development and the lack of incentives and constraints in low-carbon task itself, which may hinder the transition to a low-carbon economy.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Low-carbon energy transition serves as both the core pathway and critical enabler for achieving sustainable development. To elucidate the logic behind local governments’ policy prioritization in low-carbon energy transitions, this study draws on government attention theory and constructs an analytical framework integrating “internal–external government relations, policy tool attributes, and policy prioritization”. Through comparative case analysis and a DCE, it empirically examines the underlying mechanisms driving differentiated energy policy prioritization among CGs. The findings reveal that, influenced by local energy-intensive industries and fiscal conditions, CGs exhibit two distinct relational models in energy transitions: vertical intergovernmental relations-dominant and government–business relations-dominant. Under the two models, the preferences for policy tool attributes diverge significantly: CGs dominated by vertical intergovernmental relations adopt an “upward-looking” approach, considering policy tools’ operability, economic attributes, clarity of indicators, and political attributes to varying degrees. CGs dominated by government–enterprise relations exhibit a “downward-looking” tendency, focusing primarily on economic attributes and operability. The study uncovers the causal mechanism through which internal–external government relations shape policy prioritization: structural heterogeneity in these relations mediates local governments’ preference weighting for policy tool attributes, ultimately leading to divergent prioritization.

The main contributions of this study lie in the following areas. (1) Proposing an attention-based analytical framework that bridges “actor characteristics” and “policy attributes”, offering new insights into why peer governments adopt heterogeneous policy sequencing. (2) Combining qualitative and quantitative methods to abstract policy sequencing logic while quantitatively measuring preference variations across policy tool attributes. (3) By analyzing energy transition policies, this study advances the understanding of local governance logic in “low-incentive, low-constraint” public affairs.

The low-carbon transformation of energy depends on local governments’ appropriate selection of policy tools. Context-specific policy prioritization strategies enable local governments to focus on key issues while setting aside minor ones, thereby effectively facilitating local low-carbon transitions. To standardize local governments’ energy policy selection behaviors, the following policy recommendations are proposed based on the aforementioned conclusions. (1) Higher-level governments should further refine the portfolio of energy policy tools to provide subordinate governments with adequate policy flexibility. Given variations in industrial structures and energy mixes, different local governments face varying degrees of pressure in energy transformation and demonstrate differing levels of initiative in emission reduction. To advance low-carbon energy transitions, higher-level governments should thoroughly consider regional governance contexts when formulating energy policy frameworks, ensuring sufficient policy options for subordinate governments to select context-appropriate tools. Concurrently, higher-level governments should leverage their centralized resource allocation capabilities to establish differentiated targets within policy tools, avoiding a “one-size-fits-all” approach. (2) Achieving the transformation of energy requires both the implementation of mandatory tools (e.g., phasing out outdated production capacity) and the regulation of hybrid policy tools (e.g., fiscal subsidies, green certificate/electricity trading). Particularly under current economic downturns, overreliance on emission standards may compromise the anticipated returns of energy-intensive enterprises, thereby diminishing their motivation for energy conservation. Local governments should therefore place greater emphasis on market-based policy tools, providing dedicated funding support and policy incentives to stimulate emission reduction initiatives among energy-intensive enterprises, ultimately fostering synergistic government–enterprise collaboration in emission reduction. (3) Establish and improve incentive–constraint mechanisms for low-carbon energy transformation. Given the current institutional environment featuring weak incentives and constraints, local governments and enterprises generally lack sufficient motivation for energy transformation and carbon reduction. At this critical juncture of economic transformation, to facilitate the achievement of China’s dual carbon goals, both central and local governments should prioritize developing effective incentive mechanisms for energy transformation. This includes systematically increasing the weight of low-carbon energy indicators in performance evaluations and flexibly guiding local energy policy implementation through measures such as direct incentives for low-carbon energy transitions.