Do Social Media Platforms Control the Sustainable Purchase Intentions of Younger People?

Abstract

1. Introduction

Summary of Previous Related Literature

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

2.2. Gratification Theory (UGT)

2.3. Social Media Marketing, Sustainable Purchase Intentions, Behavioural Engagement and Content Quality

2.4. Content Quality and Sustainable Purchase Intentions

2.5. Behavioural Engagement and Sustainable Purchase Intentions

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Data Collection and Procedure

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.1.1. Convergent Validity

4.1.2. Discriminant Validity

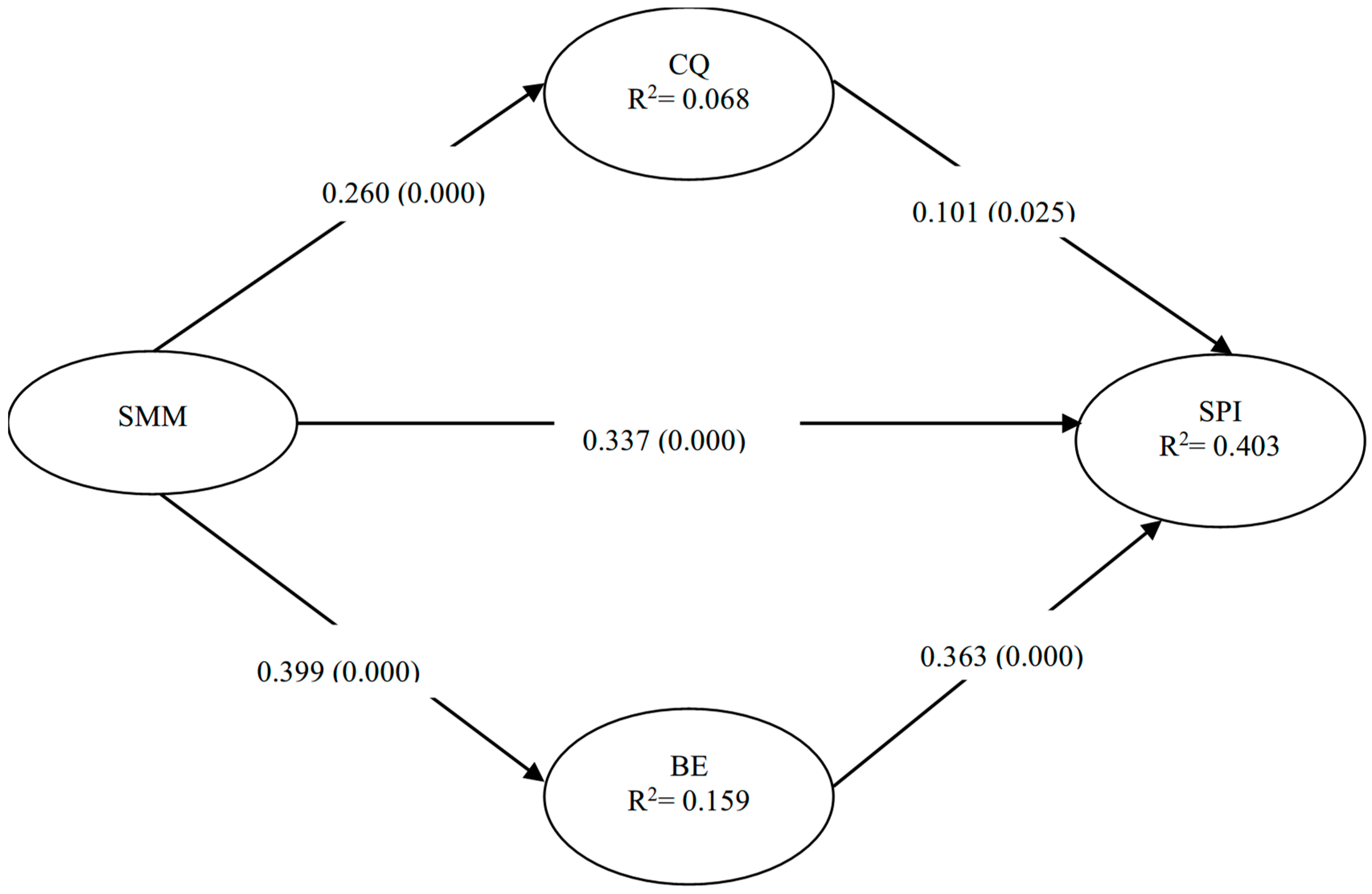

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

4.2.1. Assessing R2, Q2 and f2

4.2.2. Hypotheses Test

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Policy Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

| SN | Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Social media marketing | ||||||

| 1 | Social media marketing provides a wide range of feedback and information on sustainable products and helps to search for the best product. | |||||

| 2 | Social media platforms offer good quality information about sustainable brand/firm. | |||||

| 3 | Social media channels also provide detailed methods on sustainability while using online media and marketing tool. | |||||

| Behavioural Engagement | ||||||

| 4 | After reading the post on sustainability shared by people on my social media network, I will press the ‘like’ button. | |||||

| 5 | After reading the post on sustainability, I will comment on it. | |||||

| 6 | After reading the post on sustainability, I will share it with my friends. | |||||

| Content Quality | ||||||

| 7 | The content I can obtain on social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.) is useful in making sustainable evaluations. | |||||

| 8 | The sustainable content I can obtain on social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.) is timely (up-to-date) | |||||

| 9 | The sustainable content I can obtain on social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.) is relevant to my need. | |||||

| 10 | The sustainable content I can obtain on social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.) provides enough detail to satisfy my informational needs. | |||||

| Purchase Intention | ||||||

| 11 | In the future, I would intend to become an online sustainable shopper. | |||||

| 12 | My intention to become an online sustainable shopper is positive and enthusiastic. | |||||

| 13 | I am capable of being an online sustainable shopper over many purchase activities. | |||||

| 14 | I have a significant intention to replace the traditional sustainable shopping pattern with sustainable E-shopping. | |||||

| 15 | While browsing a product, I plan to conduct the sustainable purchase process online. |

References

- Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Ali, H.; Ali Raza, M.; Ali, G.; Aman, J.; Bano, S.; Nurunnabi, M. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices and Environmental Factors through a Moderating Role of Social Media Marketing on Sustainable Performance of Business Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Tran, M.D. Responsible Entrepreneurship and Social Legitimacy in Turbulent and Demanding Market Environments. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management [Internet]. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/csr.3131 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Udeh, E.; Dugba, A. An analysis of the potential integration’s of sustainability into marketing strategies by companies. Eur. J. Manag. Mark. Stud. 2025, 9. Available online: https://oapub.org/soc/index.php/EJMMS/article/view/1887 (accessed on 16 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nabivi, E. The Role of Social Media in Green Marketing: How Eco-Friendly Content Influences Brand Attitude and Consumer Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakiv, V.; Koval, O.; Kdyrova, I.; Voitenko, I. The Role of Cultural and Ethnic Identity in Contemporary Media Dynamics: Market Potential and Influence. Salud Cienc. Y Tecnol. Ser. De Conf. 2025, 4, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Guan, J.; Zou, T.; Shi, T.; Liu, K. How to Use Social Media and Artificial Intelligence to Promote Mental Health Among Chinese and Chinese American College Students in the U.S. Curr Psychol [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-025-07790-3 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Aldamen, Y. Social Media, Digital Resilience, and Knowledge Sustainability: Syrian Refugees’ Perspectives. J. Intercult. Commun. 2025, 25, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.T. How user-generated content on social media platform can shape consumers’ purchase behavior? An empirical study from the theory of consumption values perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2471528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Larimo, J.; Leonidou, L.C. Social media marketing strategy: Definition, conceptualization, taxonomy, validation, and future agenda. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andzulis, J.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A. A Review of Social Media and Implications for the Sales Process. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2012, 32, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.; Stephen, A.T. A Thematic Exploration of Digital, Social Media, and Mobile Marketing: Research Evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an Agenda for Future Inquiry. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichner, T.; Grünfelder, M.; Maurer, O.; Jegeni, D. Twenty-Five Years of Social Media: A Review of Social Media Applications and Definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Deng, T.; Cheng, H. The role of social media advertising in hospitality, tourism and travel: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3419–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Chen, S.C.; Wiangin, U.; Ma, Y.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Customer Behavior as an Outcome of Social Media Marketing: The Role of Social Media Marketing Activity and Customer Experience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Dialogic communication on social media: How organizations use Twitter to build dialogic relationships with their publics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, E.; Topçu, B. An Examination of the Factors Influencing Consumers’ Attitudes Toward Social Media Marketing. J. Internet Commer. 2011, 10, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus, J.A.L.; Carranza MTDla, G.; Revilla, M.S.; López-Lemus, J.G. The Role of Social Media and Innovation in Mexican Industrial Entrepreneurship. Innovar 2024, 34, e98533. [Google Scholar]

- Rosário, A.; Raimundo, R. Consumer Marketing Strategy and E-Commerce in the Last Decade: A Literature Review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3003–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.K.P.D.; Dahnil, M.I.; Yi, W.J. The Impact of Social Media Marketing Medium toward Purchase Intention and Brand Loyalty among Generation Y. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.S.; et al. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, G.; Grewal, L.; Hadi, R.; Stephen, A.T. The future of social media in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, S. Social Media Users 2024 (Global Data & Statistics) [Internet]. Priori Data . 2024. Available online: https://prioridata.com/data/social-media-usage/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Obermayer, N.; Kővári, E.; Leinonen, J.; Bak, G.; Valeri, M. How social media practices shape family business performance: The wine industry case study. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 40, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palalic, R.; Ramadani, V.; Mariam Gilani, S.; Gërguri-Rashiti, S.; Dana, L. Social media and consumer buying behavior decision: What entrepreneurs should know? Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 1249–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, K.; Dunnan, L.; Gul, R.F.; Shehzad, M.U.; Gillani, S.H.M.; Awan, F.H. Role of Social Media Marketing Activities in Influencing Customer Intentions: A Perspective of a New Emerging Era. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.808525/full (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Khorsheed, R.; Sadq, Z.; Othman, B. The Impacts of Using Social Media Websites for Efficient Marketing. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020, 12, 2221–2235. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, L. How Social-Network Attention and Sentiment of Investors Affect Commodity Futures Market Returns: New Evidence from China. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231152131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S. Understanding consumers’ intentions to purchase green products in the social media marketing context. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud Md Naz, F.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Transforming consumers’ intention to purchase green products: Role of social media. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohaimmeed, B. The Effects of Social Media Marketing Antecedents on Social Media Marketing, Brand Loyalty and Purchase Intention: A Customer Perspective. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, S.; Pusriadi, T.; Hakim, Y.P.; Darma, D.C. The Effect of Social Media Marketing, Word of Mouth, And Effectiveness of Advertising on Brand Awareness and Intention to Buy. J. Manaj. Indones. 2019, 19, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, P.; Nadhila, V.; Sanny, L. Effect of social media marketing on Instagram towards purchase intention: Evidence from Indonesia’s ready-to-drink tea industry. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2020, 4, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.H.; Ferreira, J.B.; Freitas ASde Ramos, F.L. The effects of social media opinion leaders’ recommendations on followers’ intention to buy. Rev. Bras. Gest. Neg. 2018, 20, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, M.; Owusu-Ansah, M.; Ashmond, A.A. The influence of social media on purchase intention: The mediating role of brand equity. Corona CG, editor. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1944008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S. Message Factors that Favourably Drive Consumer’s Attitudes and Behavioural Intentions Towards Social Network and Media Platforms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK, 2019. Available online: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1123&context=pbs-theses (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Hagger, M.S.; Cheung, M.W.L.; Ajzen, I.; Hamilton, K. Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClure, C.; Seock, Y.K. The role of involvement: Investigating the effect of brand’s social media pages on consumer purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ho, S.S. Applying the theory of planned behavior: Examining how communication, attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control relate to healthy lifestyle intention in Singapore. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2020, 13 (Suppl. S1), 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, F.; Men, J. Understanding consumers’ continuance intention toward recommendation vlogs: An exploration based on the dual-congruity theory and expectation-confirmation theory. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 59, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, K.H. How social capital impacts the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas Naqvi, M.H.; Jiang, Y.; Miao, M.; Naqvi, M.H. The effect of social influence, trust, and entertainment value on social media use: Evidence from Pakistan. Wu YCJ, editor. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1723825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kuang, W. Exploring Influence Factors of WeChat Users’ Health Information Sharing Behavior: Based on an Integrated Model of TPB, UGT and SCT. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athwal, N.; Istanbulluoglu, D.; McCormack, S.E. The allure of luxury brands’ social media activities: A uses and gratifications perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 32, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media engagement behaviour: A uses and gratifications perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2016, 24, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ahiabor, D.K.; Kosiba, J.P.B.; Gli, D.D.; Tweneboah-Koduah, E.Y.; Hinson, R.E. Satellite fans engagement with social networking sites influence on sport team brand equity: A UGT perspective. Digit. Bus. 2023, 3, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccastoro, S.; Gabrielsson, M.; Pullins, E.B. The integrated use of social media, digital, and traditional communication tools in the B2B sales process of international SMEs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febriyantoro, M.T. Exploring YouTube Marketing Communication: Brand awareness, brand image and purchase intention in the millennial generation. Wright LT, editor. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1787733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bïlgïn, Y. The Effect of Social Media Marketing Activities on Brand Awareness, Brand Image and Brand Loyalty. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2018, 6, 128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.T.; Cam, T.L.T.; Thi, N.N.; Phuong, V.L.N. Do corporate social responsibility drive sustainable purchase intention? An empirical study in emerging economy. Benchmarking Int. J. 2024, 32, 1141–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Goh, M.L.; Mohd Noor, M.N.B. Understanding purchase intention of university students towards skin care products. PSU Res. Rev. 2019, 3, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, D.; Herlina, M.; Boetar, A. The effect of social media marketing on purchase intention in fashion industry. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitri, C.; Hurriyati, R.; Wibowo, L.; Hendrayati, H. The role of social media marketing and brand image on smartphone purchase intention. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K. Social media marketing and customers’ passion for brands. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 38, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Correia, R.F.; Martins, J. Digital Marketing Impact on Rural Destinations Promotion: A conceptual model proposal. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Chaves, Portugal, 23–26 June 2021; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9476533?casa_token=0FoexkhGlswAAAAA:uwoGEDeeAnczpsRNNbGGqxtY6eKgAQT2myR2hmlbC9FKtj3zrIwTX_W8ONajtKUDic6ccqMC (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Naseri, Z.; Noroozi Chakoli, A.; Malekolkalami, M. Evaluating and ranking the digital content generation components for marketing the libraries and information centres’ goods and services using fuzzy TOPSIS technique. J. Inf. Sci. 2023, 49, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami Pour, M.; Karimi, Z. An integrated framework of digital content marketing implementation: An exploration of antecedents, processes, and consequences. Kybernetes 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvanović, B.; Zutshi, A.; Grilo, A.; Nodehi, T. Linking the potentials of extended digital marketing impact and start-up growth: Developing a macro-dynamic framework of start-up growth drivers supported by digital marketing. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 186, 122128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.A.; Marques, S.; Dias, Á. The impact of digital influencers’ characteristics on purchase intention of fashion products. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, D.; Zakieva, R.R.; Kuznetsova, M.; Ismael, A.M.; Ahmed, A.A.A. Generating destination brand awareness and image through the firm’s social media. Kybernetes 2022, 52, 3292–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, O. The effect of brands’ social network content quality and interactivity on purchase intention: Evidence from Jordan. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3135–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, T.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Thomas, A.; Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C. Digital ecosystem and consumer engagement: A socio-technical perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaoui, C.; Webster, C.M. Brand and consumer engagement behaviors on Facebook brand pages: Let’s have a (positive) conversation. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Santini, F.; Ladeira, W.J.; Pinto, D.C.; Herter, M.M.; Sampaio, C.H.; Babin, B.J. Customer engagement in social media: A framework and meta-analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Wasim, S.; Irfan, S.; Gogoi, S.; Srivastava, A.; Farheen, Z. Qualitative v/s. Quantitative Research—A Summarized Review. Population 2019, 6, 2828–2832. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. The development and validation of the scholar–practitioner research development scale for students enrolled in professional doctoral programs. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2018, 10, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koran, N.; Berkmen, B.; Adalıer, A. Mobile technology usage in early childhood: Pre-COVID-19 and the national lockdown period in North Cyprus. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sürücü, L.; Yıkılmaz, İ.; Maşlakçı, A. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) in Quantitative Researches and Practical Considerations. Gümüşhane Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2024, 13, 947–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A. Chapter 5—Google Form. In Open Electronic Data Capture Tools for Medical and Biomedical Research and Medical Allied Professionals [Internet]; Pundhir, A., Mehto, A.K., Jaiswal, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 331–378. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780443156656000087 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Zeng, N. Reform: Refactorized Electronic Web Forms—Large Scale Survey Data Capture and Workflow Control Framework [Internet]; Case Western Reserve University: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2017; Available online: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/etd/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=case1496839127238529 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Obeng, H.A.; Arhinful, R.; Tessema, D.H.; Nuhu, J.A. The mediating role of organisational stress in the relationship between gender diversity and employee performance in Ghanaian public hospitals. Future Bus. J. 2025, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuwel, D.; Ahmed, J.; Nwosu, L.; Aigbiremhon, J. The effect of patient relationship management on patient loyalty in Buea, Cameroon: Mediating role of patient satisfaction. Quant. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2023, 4, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, D.H.; Nuhu, J.A.; Obeng, H.A.; Assefa, H.K. The Relationship Between Total Quality Management, Patient Satisfaction, Service Quality, and Trust in the Healthcare Sector: The Case Of Ethiopian Public Hospitals. Uasbd 2024, 8, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, H.; Tessema, D.H.; Nuhu, J.A.; Atan, T.; Tucker, J.J. Enhancing Job Performance: Exploring the Impact of Employee Loyalty and Training on Quality Human Resources Practices. Uluslararası Anadolu Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2024, 8, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Non-Normality Propagation among Latent Variables and Indicators in PLS-SEM Simulations. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2016, 15, 16. Available online: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jmasm/vol15/iss1/16 (accessed on 17 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bayonne, E.; Marin-Garcia, J.A.; Alfalla-Luque, R. Partial least squares (PLS) in Operations Management research: Insights from a systematic literature review. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2020, 13, 565–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, M.; Alshurideh, M. The effect of digital marketing on purchase intention: Moderating effect of brand equity. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrei, G.; Filieri, R.; Kennedy, L. Social media interactions, purchase intention, and behavioural engagement: The mediating role of source and content factors. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Banerjee, R.; Dagar, V. Analysis of Impulse Buying Behaviour of Consumer During COVID-19: An Empirical Study. Millenn. Asia 2023, 14, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Gahfoor, R.Z. Satisfaction and revisit intentions at fast food restaurants. Future Bus. J. 2020, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, L.; Yesilada, F.; Aghaei, I.; Nuhu, J.A. The impact of perceived physician communication skills on revisit intention: A moderated mediation model. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2025, 27, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyabi, M.; Özgit, H.; Ahmed, J.N. Sustaining Digital Marketing Strategies to Enhance Customer Engagement and Brand Promotion: Position as a Moderator. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crudu, V. Exploring the Significance of R-Squared for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Your Regression Model [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://moldstud.com/articles/p-exploring-the-significance-of-r-squared-for-evaluating-the-effectiveness-of-your-regression-model (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Tessema, D.H.; Yesilada, F.; Aghaei, I.; Ahmed, J.N. Influence of Perceived Service Quality on Word-of-Mouth: The Mediating Role of Brand Trust and Student Satisfaction. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2024. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jarhe-06-2024-0299/full/html (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Uno, S.S.; Supratikno, H.; Ugut, G.S.S.; Bernarto, I.; Antonio, F.; Hasbullah, Y. The effects of entrepreneurial values and entrepreneurial orientation, with environmental dynamism and resource availability as moderating variables, on the financial performance and its impacts on firms’ future intention: Empirical evidences from Indonesian state-owned enterprises. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3693–3700. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, T.V.T.; Nguyen, H.V.; Phan, M.C.T. Influences of Job Demands, Job Resources, Personal Resources, and Coworkers Support on Work Engagement and Creativity. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Fey, C.F.; Hu, T.; Delios, A. The Measurement and Communication of Effect Sizes in Management Research. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2023, 19, 176–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, J.A.; Yesilada, F.; Aghaei, I. A Critical Assessment of Male HIV/AIDS Patients’ Satisfaction with Antiretroviral Therapy and Its Implications for Sustainable Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2025. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jhom-01-2024-0009/full/html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Omar, A.M. The Effect of Human Capital Development on Strategic Renewal in the Egyptian Hospitality Industry: The Moderating Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Int. Bus. Res. 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Neto, G.C.; Pinto, L.F.R.; de Silva, D.; Rodrigues, F.L.; Flausino, F.R.; de Oliveira, D.E.P. Industry 4.0 Technologies Promote Micro-Level Circular Economy but Neglect Strong Sustainability in Textile Industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilada, F.; Tshala, A.; Ahmed, J.; Nwosu, L. The role of perceived telemedicine quality in enhancing patient satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediation of telemedicine satisfaction. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2025, 7, 2025127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.R.A.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.H.M. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. In Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets; Leeflang, P.S.H., Wieringa, J.E., Bijmolt, T.H.A., Pauwels, K.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 361–381, (International Series in Quantitative Marketing). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirgiatmo, Y. Testing the Discriminant Validity and Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio of Correlation (HTMT): A Case in Indonesian SMEs. In Macroeconomic Risk and Growth in the Southeast Asian Countries: Insight from Indonesia; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 157–170. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/s1571-03862023000033a011/full/html (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Qasim, D.; Bataineh, A.Q.; Abu-Dawwas, W. The impact of information management strategies on decision-making effectiveness in Jordanian private hospitals. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2025, 23, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B.; Wen, J.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Al-Emran, M.; Al-Sharafi, M.A. Determinants of Generative AI in Promoting Green Purchasing Behavior: A Hybrid Partial Least Squares–Artificial Neural Network Approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 4072–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintimehin, O.O.; Eniola, A.A.; Alabi, O.J.; Eluyela, D.F.; Okere, W.; Ozordi, E. Social capital and its effect on business performance in the Nigeria informal sector. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Cheah, J.H.; Gholamzade, R.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 35, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Meadows, M.; Wong, D.; Xia, S. Understanding consumers’ social media engagement behaviour: An examination of the moderation effect of social media context. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.; Moghavvemmi, S.; Suberamanaian, K.; Zanuddin, H.; Bin Md Nasir, H.N. Mediating impact of fan-page engagement on social media connectedness and followers purchase intention. Online Inf. Rev. 2018, 42, 1082–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic Dialogic Communication Through Digital Media During COVID-19 Crisis. In Strategic Corporate Communication in the Digital Age; Camilleri, M.A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbous, A.; Barakat, K.A. Bridging the online offline gap: Assessing the impact of brands’ social network content quality on brand awareness and purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağtaş, S. The effect of social media marketing on brand equity and consumer purchasing intention. J. Life Econ. 2022, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J. Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common Method Bias: It’s Bad, It’s Complex, It’s Widespread, and It’s Not Easy to Fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yuan, G.; Xue, R.; Han, Y.; Taylor, J.E. Mitigating Common Method Bias in Construction Engineering and Management Research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qangule, L. Addressing Common Method Bias in Survey Datasets: A Literature Review and Future Research Directions; University of the Witwatersrand: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2024; Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/3196613217/abstract/A2FFA61F967C4B97PQ/1 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Akter, S.; Fosso, W.; Samuel Dewan, S. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle; Christian, M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. PLS-SEM: Looking Back and Moving Forward. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, F.; Inrawan Wiratmadja, I. Driving Sustainable Performance in SMEs Through Frugal Innovation: The Nexus of Sustainable Leadership, Knowledge Management, and Dynamic Capabilities. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 103329–103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supotthamjaree, W.; Srinaruewan, P. The impact of social media advertising on purchase intention: The mediation role of consumer brand engagement. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2021, 15, 498–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B. Are information quality and source credibility really important for shared content on social media? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursaris, C.K.; Van Osch, W.; Balogh, B.A. Do Facebook Likes Lead to Shares or Sales? Exploring the Empirical Links between Social Media Content, Brand Equity, Purchase Intention, and Engagement. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 3546–3555. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7427628?casa_token=J6qcZPGpeUUAAAAA:WYfBPxckU7rhpVU_PpyX3P-rMA9eWs0v2wLba8vdg9ALeyyQGlbmwNdYRBRhTjMotBhzBJ8x (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Putri, W.M.; Sutiono, H.T.; Kusmantini, T. Mediation of Brand Equity in The Influence of Integrated Marketing Communication on Purchase Intention of Mie Gacoan Restaurant in Yogyakarta. Manaj. Dan Kewirausahaan 2024, 5, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Syed, A.A. Impact of online social media activities on marketing of green products. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022, 30, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 244 | 54.2 |

| Male | 206 | 45.8 | |

| Level of education | Undergraduate | 353 | 78.4 |

| Masters | 69 | 15.3 | |

| PhD | 28 | 6.2 | |

| Age | 18–20 | 121 | 26.9 |

| 21–25 | 175 | 38.9 | |

| 26–30 | 81 | 18.0 | |

| 31–35 | 40 | 8.9 | |

| 36–40 | 23 | 5.1 | |

| 41 and above | 10 | 2.2 | |

| Social Media Platform used | 167 | 37.1 | |

| 171 | 38.0 | ||

| 92 | 20.4 | ||

| Vkontakte | 20 | 4.4 |

| Loading | α | CR | AVE | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE1 | 0.884 | 2.122 | |||

| BE2 | 0.875 | 0.848 | 0.908 | 0.767 | 2.011 |

| BE3 | 0.867 | 2.028 | |||

| CQ1 | 0.911 | 3.540 | |||

| CQ2 | 0.828 | 2.229 | |||

| CQ3 | 0.849 | 0.898 | 0.928 | 0.765 | 1.958 |

| CQ4 | 0.907 | 3.597 | |||

| SPI1 | 0.854 | 2.531 | |||

| SPI2 | 0.901 | 4.933 | |||

| SPI3 | 0.884 | 0.910 | 0.933 | 0.735 | 2.952 |

| SPI4 | 0.806 | 1.969 | |||

| SPI5 | 0.838 | 3.678 | |||

| SMM1 | 0.839 | 1.856 | |||

| SMM2 | 0.869 | 1.884 | |||

| SMM3 | 0.891 | 0.835 | 0.900 | 0.751 | 2.170 |

| BE | CQ | SPI | SMM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE | 0.876 | |||

| CQ | 0.435 | 0.874 | ||

| SPI | 0.541 | 0.346 | 0.857 | |

| SMM | 0.399 | 0.260 | 0.508 | 0.867 |

| BE | CQ | SPI | SMM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE | ||||

| CQ | 0.497 | |||

| SPI | 0.614 | 0.376 | ||

| SMM | 0.471 | 0.290 | 0.578 |

| Q2 Predict | R-Square | f-Square | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BE | 0.152 | 0.159 | |

| CQ | 0.058 | 0.068 | |

| SPI | 0.253 | 0.403 | |

| BE → SPI | 0.160 | ||

| CQ → SPI | 0.014 | ||

| SMM → BE | 0.189 | ||

| SMM → CQ | 0.073 | ||

| SMM → SPI | 0.158 |

| Hypothesis | β | Mean | SD | T Statistics | P Values | Bias Corrected Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | 2.5% | 97.5% | Decision | |||||||

| H1 | SMM → SPI | 0.337 | 0.337 | 0.050 | 6.710 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.235 | 0.432 | Supported |

| H2 | SMM → BE | 0.399 | 0.400 | 0.048 | 8.316 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.296 | 0.486 | Supported |

| H3 | SMM → CQ | 0.260 | 0.261 | 0.056 | 4.647 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.145 | 0.366 | Supported |

| H4 | BE → SPI | 0.363 | 0.362 | 0.057 | 6.362 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.246 | 0.471 | Supported |

| H5 | CQ → SPI | 0.101 | 0.102 | 0.045 | 2.247 | 0.025 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.187 | Supported |

| Control | ||||||||||

| Social Media Platforms ← SPI | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.036 | 1.950 | 0.051 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.141 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, J.N.; Adalıer, A.; Özgit, H.; Kamyabi, M. Do Social Media Platforms Control the Sustainable Purchase Intentions of Younger People? Sustainability 2025, 17, 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125488

Ahmed JN, Adalıer A, Özgit H, Kamyabi M. Do Social Media Platforms Control the Sustainable Purchase Intentions of Younger People? Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125488

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Japheth Nuhu, Ahmet Adalıer, Hale Özgit, and Marjan Kamyabi. 2025. "Do Social Media Platforms Control the Sustainable Purchase Intentions of Younger People?" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125488

APA StyleAhmed, J. N., Adalıer, A., Özgit, H., & Kamyabi, M. (2025). Do Social Media Platforms Control the Sustainable Purchase Intentions of Younger People? Sustainability, 17(12), 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125488

_Li.png)