1. Introduction

Community-led rural tourism is a powerful catalyst for both economic sustainability and cultural preservation, primarily by engaging local communities in active participation and management of tourism activities [

1]. Community involvement is paramount in the successful development of rural tourism, as it ensures that local needs and values are prioritized, fostering a sense of ownership among residents [

2]. Engaging community members in the tourism planning process can take several forms, including workshops, surveys, and collaborative projects that allow individuals to voice their opinions and contribute to decision-making [

3].

While the benefits of community-led rural tourism are widely recognized, the existing literature often overlooks or insufficiently addresses critical social and psychological dimensions that shape the success and sustainability of these initiatives. In particular, residents’ motivation to engage in tourism development, their sense of local empowerment, and their feeling of sustainable belonging are key factors that influence participation and commitment but remain underexplored. Residents’ motivation is linked to their perception of how tourism development affects their lives and livelihoods [

4,

5,

6], while empowerment refers to the extent to which they feel capable of influencing tourism policies and outcomes [

7,

8]. Sustainable belonging captures a deeper connection to place, community identity, and stewardship of cultural and natural heritage [

9]. These elements form the conceptual foundation for understanding community engagement in rural tourism, yet they are often missing or only superficially incorporated in studies and models. When residents are motivated and empowered, they tend to actively support and co-manage tourism activities, ensuring that these initiatives respect local cultural values and contribute to long-term community well-being. Sustainable belonging strengthens social cohesion and promotes eco-friendly practices, thereby enhancing both environmental preservation and the social fabric of rural communities. These interrelated elements form the conceptual foundation for this study.

Sustainable practices in rural tourism are essential to mitigate the environmental impact of increased visitor numbers while enhancing the overall travel experience [

10,

11,

12,

13]. At its core, sustainability in tourism encompasses the principles that advocate for responsible resource management, cultural preservation, and economic equity [

14]. Rural tourism operators can adopt various eco-friendly practices, such as utilizing renewable energy sources, implementing waste reduction strategies, and promoting local food sourcing [

15]. According to Bojović et al., [

16], several rural bed-and-breakfasts have adopted solar energy systems to power their facilities, significantly reducing their carbon footprint. According to Shenyoputro et al., [

17], sustainability in tourism, through initiatives like the “Leave No Trace” program, encourages visitors to minimize their environmental impact by following guidelines that respect local ecosystems. The benefits of sustainable tourism extend beyond environmental protection; they also contribute to local economies by attracting eco-conscious travelers who are willing to pay a premium for sustainable experiences [

18,

19,

20,

21]. This alignment between tourism and sustainability not only preserves the natural beauty that draws visitors to rural areas but also enhances the quality of life for residents, creating a win–win scenario for both communities and tourists [

22,

23,

24].

The economic impacts of revitalizing rural tourism are profound, particularly in terms of job creation and income generation for local communities [

25,

26,

27]. As tourism expands, new opportunities emerge in sectors such as hospitality, agriculture, and local arts, which can lead to a significant reduction in unemployment rates [

28]. According to Mehra et al., [

29], the revitalization of tourism in the Appalachian region of the United States has led to the creation of numerous jobs in guided outdoor adventures, handmade crafts, and local dining establishments. According to Boley et al., [

30], the revenue generated from tourism can enhance local infrastructure and services, enabling communities to invest in roads, healthcare, and education. As tourism-related income flows into these areas, the multiplier effect can lead to improved living standards and access to essential services [

31]. Moreover, the diversification of rural economies through tourism can bolster long-term economic resilience [

32]. By reducing reliance on traditional industries, such as agriculture or mining, communities can better withstand economic fluctuations and shifts in market demand. In this way, revitalizing rural tourism not only sustains local economies but also enhances their adaptive capacity in an ever-changing global landscape [

33].

A key reference point in this study is the Bregenzerwald model of rural tourism development in Austria, which exemplifies a high-functioning community-based approach rooted in cultural heritage preservation, environmental stewardship, and collective decision-making. The Bregenzerwald model from Austria offers a compelling conceptual framework that explicitly incorporates these three pillars—community participation, local empowerment, and sustainable belonging—as essential for sustainable rural tourism development. Originating from decades of community-driven initiatives in the Bregenzerwald region, this model is grounded in three core assumptions: (1) active and inclusive participation of community members in all stages of tourism planning and management; (2) empowerment that enables residents to shape tourism development and equitably share its benefits; and (3) fostering sustainable belonging, which integrates economic development with preservation of cultural identity and environmental stewardship. This triadic framework has led to strong social cohesion, cultural valorization, and economic prosperity, making it a benchmark for inclusive and sustainable rural tourism practices. The Bregenzerwald region has successfully implemented a locally embedded tourism system that emphasizes regional identity, architectural integrity, and social cohesion, supported by a strong policy framework and stakeholder cooperation. It assumes that rural tourism development achieves long-term success only when residents actively engage in decision-making processes, share a sense of ownership, and balance economic growth with cultural preservation and environmental sustainability. The Bregenzerwald model has demonstrated the effectiveness of fostering social cohesion, environmental stewardship, and economic resilience through inclusive governance and local collaboration. Given its success, the model provides a valuable benchmark and transferable framework for rural regions aiming to develop sustainable tourism, which this study seeks to test and adapt in the context of Fruška Gora, Serbia.

The study was initiated based on the foundational hypothesis (H) that the willingness of local residents to participate in tourism initiatives serves as a crucial catalyst for the sustainable development of rural tourism. This premise recognizes that the active involvement of local communities is not merely a supportive element, but a driving force behind the success and sustainability of tourism in rural areas. Residents’ engagement ensures that tourism development aligns with the local needs, values, and long-term interests, fostering a model of growth that is economically viable, socially inclusive, and environmentally responsible. Without the support and participation of the local population, tourism initiatives risk being unsustainable, culturally insensitive, or economically disconnected from the community they aim to benefit. Understanding the factors that motivate or inhibit resident participation is essential for designing tourism strategies that are genuinely sustainable and capable of enhancing rural vitality. The initial factor analysis revealed two factors, tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging, which together accounted for 84.655% of the variance. The findings suggest that tourism is recognized as a catalyst for regional prosperity, job creation, and local economic empowerment, with a strong community awareness of the need to balance modernization with cultural preservation. The first factor, tourism empowerment, reflects residents’ perceptions of tourism as a driver of local prosperity and cultural valorization, confirming that higher perceived tourism empowerment positively influences community engagement in sustainable tourism development. The second factor, sustainable belonging, emphasizes the community’s preference for eco-friendly tourism practices that enhance environmental consciousness and social cohesion.

The research aims to bridge the gap between best practices in rural tourism development from an established region (Bregenzerwald, Austria) and the potential for similar development in the villages of Fruška Gora, Serbia. By examining stakeholder perceptions in Fruška Gora through a structured framework based on tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging, this study will provide valuable insights into the following: Local Readiness for Sustainable Tourism (whether Fruška Gora stakeholders are aware of the opportunities rural tourism offers, and whether they are prepared to support and implement sustainable tourism practices), Applicability of Best Practices (the transferability of lessons learned from Bregenzerwald to the context of Fruška Gora, with particular attention to cultural, economic, and environmental differences), and Strategic Planning for Future Development (providing evidence-based recommendations for tourism policy, community engagement, and sustainable development strategies tailored to Fruška Gora). The results highlight the importance of sustainable practices and community connectivity in rural tourism development, positioning the Bregenzerwald community as a model for inclusive and sustainable growth. Overall, the research contributes to the understanding of rural tourism development and proposes a framework that can be adapted in other rural settings across Europe.

2. Literature Review

The extent to which residents will actively engage in community-led tourism development depends on several interrelated factors. According to Huang et al. [

34,

35], perceived personal and collective benefits play a crucial role; when residents recognize that tourism initiatives contribute to economic opportunities, improved quality of life, and cultural preservation, they are more likely to become proactive participants [

36]. The perceived benefits of tourism, both personal and collective, play a significant role in determining resident participation in tourism initiatives [

37]. Economic opportunities are often at the forefront of these perceptions, as residents who recognize the potential for financial gain from tourism tend to exhibit stronger support for development projects, whether they be mass or alternative forms of tourism [

38].

Quality of life improvements, identified as a primary outcome in the tourism literature, also heavily influence residents’ attitudes toward supporting tourism development [

39]. When residents perceive that tourism contributes positively to their overall well-being, they are more likely to engage in tourism activities and initiatives [

40]. According to Gautam and Bhalla [

41], the integration of various life domains and quality of life metrics indicates that residents’ satisfaction across these domains directly affects their outlook on tourism, suggesting that contentment in one area can enhance support in another [

42]. Cultural preservation emerges as another critical factor; residents often weigh the potential cultural benefits of tourism against the risks of cultural dilution [

43]. A positive perception of tourism’s impact on cultural preservation can lead to increased support for alternative tourism development, as it aligns with community values and identity [

44].

According to Petrovszki et al., [

45], residents who perceive negative socioeconomic impacts, such as increased costs of living or loss of community integrity, may strongly oppose mass tourism initiatives while remaining ambivalent towards alternative options. Thus, understanding the multifaceted perceptions of residents regarding economic opportunities, quality of life improvements, and cultural preservation is essential for fostering meaningful participation in sustainable tourism initiatives [

46]. According to Gutierrez [

47], a sense of ownership and empowerment is fundamental. Residents who feel they have a meaningful voice in decision-making processes, and who perceive tourism projects as aligned with local values and needs, are more motivated to take the lead [

48].

The interplay between perceived community engagement and the alignment of tourism projects with local values significantly impacts resident leadership motivation in decision-making processes [

49]. When local residents perceive that their values and interests are reflected in tourism initiatives, they are more likely to feel a sense of obligation to contribute positively to the development of their community’s tourism destination [

50]. This perceived alignment fosters a deeper commitment among residents, encouraging them to advocate for their interests and influence tourism development effectively [

51]. According to Islam et al. [

52], as residents engage in advocacy efforts, they often provide positive recommendations that not only enhance their control over the tourism site but also strengthen their leadership roles within the community. Such participation in decision-making processes empowers residents, allowing them to voice their concerns and ideas, which in turn creates a more inclusive environment for tourism development [

53].

The role of place attachment in fostering sustainable tourism is profoundly rooted in the emotional and cultural connections that residents develop with their communities [

54]. This attachment not only shapes individual identities but also translates into actionable behaviors aimed at preserving and reconstructing cultural heritage. According to Prayag and Manci [

55], the emotional bonds that residents form can lead to the creation of shared cultural narratives, which enhance collective memory and foster a sense of community pride, further motivating them to participate in sustainable practices. Understanding these emotional connections is essential for heritage planners, as they can leverage place attachment to encourage responsible behavior among residents, ultimately promoting environmental preservation and cultural sustainability [

1]. In this context, the integration of emotional solidarity into the planning process can facilitate deeper community involvement in tourism, as residents feel empowered to act as stewards of their cultural heritage while also enhancing their own quality of life [

47]. Thus, recognizing the significance of place attachment in the relationship between residents and their communities is vital for the successful implementation of sustainable tourism initiatives that respect and preserve cultural heritage.

According to Torabi et al. [

56], the availability of resources and skills, such as education, financial support, and capacity-building programs, determines the extent to which community members feel capable of successfully leading tourism initiatives. Capacity building is fundamental in this respect, as it enables local communities to participate actively in sustainable tourism development, thereby fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility among community members [

57]. By investing in capacity building, communities can cultivate the necessary expertise to manage tourism effectively, ensuring that their initiatives are not only sustainable but also economically viable and culturally relevant. Mirčetić and Mihić [

58] also emphasized utilizing technological advancements in tourism as a sustainable method. In line with that, the importance of cyber security as one of the contemporary topics in tourism should be underlined [

59]. According to Stangl et al. [

60], active participation in tourism activities allows community members to reap the benefits of tourism development, creating a direct link between their involvement and the economic advantages that tourism can provide. To maximize these benefits, it is crucial to offer training and educational opportunities that enhance the skills, knowledge, and capabilities of community members, empowering them to take on leadership roles within their tourism initiatives [

61].

Recent developments in community-led rural tourism underscore a range of challenges and opportunities that are reshaping the field. Technologically, the growing accessibility of digital tools—such as geolocation-based services, smart applications, and digital storytelling platforms—offers rural communities novel means to engage tourists and promote local experiences. However, limited digital infrastructure and a lack of digital literacy in many rural areas remain key challenges to effective implementation [

62]. Cybersecurity concerns have become increasingly relevant, particularly as communities adopt online booking systems and data-driven management platforms [

63]. Economically, while rural tourism presents opportunities for income diversification and micro-entrepreneurship, communities often face obstacles related to insufficient funding, lack of investment incentives, and overreliance on seasonal demand [

64]. In this regard, public–private partnerships and community cooperatives have emerged as promising models to ensure more resilient and inclusive rural tourism economies [

65]. Socially, demographic shifts such as youth outmigration and an aging population hinder local participation in tourism initiatives. Recent efforts to involve youth in heritage-based tourism and agrotourism ventures have shown potential to reinvigorate local engagement and foster intergenerational knowledge exchange [

66]. Overall, while rural communities continue to grapple with systemic limitations, the convergence of technological innovation, targeted economic support, and inclusive social strategies offers a viable path forward for enhancing community-led tourism development. Integrating these contemporary dimensions into sustainable tourism planning is crucial to ensuring long-term benefits and local empowerment [

48].

3. Materials and Methods

The research was divided into two parts. The first part of the research concerned the local population of the Bregenzerwald region (Austria), while the second part of the research was conducted among leading stakeholders in the territory of Fruška Gora (Serbia). The idea was to present the development of sustainable rural tourism in the Bregenzerwald region as a model that should be followed in an effort to develop rural tourism in a sustainable way, the only desirable one. The region’s approach to sustainable rural tourism has been recognized for its harmonious blend of traditional architecture and modern design, as well as its commitment to environmental stewardship. This makes Bregenzerwald a compelling case study for exploring the role of rural tourism in advancing sustainable rural destination development.

The Bregenzerwald region comprises 23 villages with a combined population of around 30,000 people. As noted by Ahmed [

67], an optimal sample size for a population of 30,000 local residents, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, would consist of 381 respondents. Therefore, the sample from Bregenzerwald that took part in the study is both valid and credible. The study sample consisted of 386 respondents from the Bregenzerwald region. In terms of gender distribution, the sample was relatively balanced, with 52.6% male respondents (

n = 203) and 47.4% female respondents (

n = 183). Regarding age structure, the largest proportion of respondents belonged to the 45–54 years age group, accounting for 25.9% of the sample (

n = 100). This was followed by participants aged 35–44 years (22.5%,

n = 87) and 25–34 years (16.3%,

n = 63). Respondents aged 55–64 years represented 15.8% (

n = 61), while the youngest group, aged 18–24 years, comprised 10.4% (

n = 40). The oldest group, those over 65 years, accounted for 9.1% of the total (

n = 35). In terms of educational attainment, the majority of the respondents had completed secondary education (54.9%,

n = 212). A substantial proportion held a higher education degree (college or university), comprising 37.8% of the sample (

n = 146). Only 5.2% (

n = 20) had completed master’s or doctoral studies, while a small minority (2.1%,

n = 8) had only an elementary education. The sample reflects a mature and moderately well-educated population, providing a strong basis for exploring the local residents’ motivations and attitudes toward sustainable rural tourism development in the Bregenzerwald region. To ensure the representativeness and reliability of the sample, a stratified random sampling method was employed, capturing diverse demographic groups across the 23 villages. The face-to-face survey method allowed for high response rates and minimized non-response bias. Data collection was carried out during multiple visits between April 2024 and April 2025, ensuring seasonal variation was accounted for. Prior to full implementation, the questionnaire underwent a pilot test with 25 participants to verify the clarity and relevance of the items and necessary adjustments were made based on the feedback received. The internal consistency of the instrument was confirmed using Cronbach’s alpha, with all the key constructs exceeding the threshold of 0.70, indicating acceptable reliability.

The paper started from the initial hypothesis H: The motivation of local residents to engage in tourism initiatives is a key driver of sustainable rural tourism development. Residents’ motivation to engage in tourism initiatives—and ultimately the success of community-led rural tourism—depends on the interaction of perceived benefits, empowerment, trust, place attachment, and access to necessary resources. In order to verify the initial hypothesis H, it was necessary to single out a region that would serve as a model by which rural tourism could be developed in any rural destination. There, the Bregenzerwald region stood out as an example of best practice, and the authors chose Fruška Gora National Park in Serbia as a “pilot” project for applying the model. Accordingly, three sub-hypotheses of the paper were distinguished:

H1a: Higher levels of perceived tourism empowerment among residents positively influence their willingness to engage in community-led sustainable tourism development.

H1b: A stronger sense of sustainable belonging among residents positively influences their support for eco-friendly and socially cohesive tourism initiatives.

H1c: The conceptual framework of rural tourism development based on the dimensions of tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging, as identified in Bregenzerwald, is recognized and positively received by stakeholders in Fruška Gora, indicating its potential applicability as a model of best practice.

Having singled out Fruška Gora as an area for the application of the model, it was necessary to define the stakeholders who would be adequate for the research. In that context, the most important decision-makers stood out. Key stakeholders were selected based on their direct roles in rural tourism development. Business owners, farmers, chefs, and hotel managers represent economic and service sectors; cultural experts and architects address heritage preservation; local guides and tourism operators offer visitor engagement insights; and local government officials ensure a policy perspective. This diverse group enables a comprehensive evaluation of sustainable, community-led tourism practices. For the purposes of the second part of the research, 31 representative stakeholders from the Fruška Gora area were selected, with whom the research took the form of interviews with pre-set questions that were compiled based on the results obtained from the previous research in Bregenzerwald. While the semi-structured interviews provided valuable insights into local stakeholder perspectives on tourism development, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the phrasing of some interview questions may have implicitly emphasized the positive aspects of tourism, potentially leading the respondents to align their answers with perceived researcher expectations. This limitation was not intentional but is important to consider when interpreting the findings. Secondly, the number of stakeholders included in the qualitative analysis was limited due to time and logistical constraints. Although efforts were made to ensure diversity among the participants (e.g., farmers, local officials, business owners, and tourism professionals), the sample size does not allow for generalization. Future studies should aim to engage a larger and more diverse group of stakeholders and use more critically framed, open-ended questions to capture a fuller range of attitudes—including possible skepticism or resistance toward tourism initiatives.

The paper adopted an epistemological orientation grounded in constructivism, wherein sustainable rural tourism development is understood as a socially constructed process, emerging from the dynamic interplay of local knowledge, community values, and contextual practices. Within this framework, sustainable rural tourism is not viewed merely as a set of externally imposed strategies, but as a phenomenon that is co-produced by residents and stakeholders through their active engagement with the cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions of their locality. By situating the Bregenzerwald model as a reference point and examining its applicability to Fruška Gora, the research underscores the critical importance of endogenous development processes that prioritize local agency, community empowerment, and the long-term stewardship of rural landscapes. This epistemological stance ensures that the inquiry remains practically anchored in the lived realities of rural communities while advancing theoretical insights into sustainable rural tourism as a participatory and place-based endeavor.

The initial step undertaken was factor analysis, which identified two distinct factors: tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging. Specifically, a group of 34 questions was presented to the local residents of the Bregenzerwald region, requiring responses to be rated on a five-point Likert scale. Between April 2024 and April 2025, the authors of the study visited the destination multiple times to conduct their research. The respondents were engaged in traditional “face-to-face” interviews, primarily conducted in local markets, restaurants, streets, and other communal areas frequented by the local populace.

In this formulation, Χᵢ represents the observed variable, corresponding to individual survey items that reflect residents’ attitudes and motivations toward rural tourism initiatives. The model assumes that each observed variable is influenced by two latent factors: F1 (tourism empowerment) and F2 (sustainable belonging). Tourism empowerment (F1) captures residents’ motivations related to economic benefits, job creation, cultural valorization, income diversification, improved quality of life, and the balance between modernization and heritage preservation. Sustainable belonging (F2) reflects residents’ motivations related to environmental stewardship, social cohesion, the promotion of eco-friendly tourism practices, and the strengthening of community identity and connectivity. The coefficients λ1 and λ2 are the factor loadings, representing the strength and direction of the relationship between each observed variable and the corresponding latent factor. Higher factor loadings indicate a stronger association between an observed variable and the respective underlying dimension. The term εᵢ represents the measurement error specific to each observed variable, capturing the variance not explained by the latent factors. By structuring the relationship between observed variables and latent constructs in this way, the study provides a robust analytical basis for validating the proposed conceptual framework of sustainable rural tourism development. This measurement model enables a deeper understanding of how the local residents’ motivations are organized around the dimensions of empowerment and sustainable belonging, supporting the overarching hypothesis that community engagement is crucial for sustainable rural tourism initiatives.

To determine the appropriate number of factors in the exploratory factor analysis, the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1) was used. This criterion supported the retention of two factors, as their eigenvalues exceeded 1 and together accounted for 84.655% of the total variance. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) extraction method was applied, and a Varimax (orthogonal) rotation was used to enhance the interpretability of the factor structure by minimizing the number of variables with high loadings on each factor. This approach facilitated a clearer understanding of the underlying constructs while maintaining orthogonality between the identified dimensions.

After extracting the underlying factors through exploratory factor analysis—identifying tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging as the principal dimensions—the study advanced to structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM was employed to test the hypothesized relationships between the latent constructs and to validate the proposed conceptual framework of sustainable rural tourism development. By modeling the causal paths and the strength of associations between the residents’ motivations and their willingness to engage in community-led tourism initiatives, SEM enabled a comprehensive evaluation of the theoretical model. This methodological approach ensured not only the identification of key motivational dimensions but also the empirical testing of their predictive power in shaping sustainable rural tourism development practices. The use of SEM thus provided a robust and systematic means of confirming the relevance of the Bregenzerwald model for potential application in the Fruška Gora region. In the context of this study, the basic structural equation can be represented as follows:

where Y denotes the endogenous (dependent) variable, X represents the exogenous (independent) variable, β is the regression coefficient reflecting the strength and direction of the relationship between X and Y, and ζ captures the error term or the portion of Y not explained by X. Applied to the present research, this model structure was used to examine how the latent constructs—tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging—(as X) predict the local residents’ or stakeholders’ willingness to engage in community-led sustainable rural tourism development (as Y). The use of this equation within the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework allowed for the assessment of both the direct effects of the identified factors and the model’s overall explanatory power, thereby strengthening the empirical foundation of the proposed conceptual framework.

Research Design and Methods Applied at Each Stage:

- ➩

Identify the motivational factors influencing local support for sustainable rural tourism.

- ➩

Define the latent constructs (tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging) based on the rural tourism, community empowerment, and place attachment literature.

- ➩

Method: Theoretical Modeling, Literature Review, and Contextual Framework Development.

- ➩

Quantitative Phase: Survey-Based Study in Bregenzerwald.

- ➩

Develop a structured questionnaire with 34 items using a five-point Likert scale.

- ➩

Collect data from 386 local residents through face-to-face interviews.

- ➩

Method: Survey Design, Sampling Strategy, and data collection.

- ➩

Quantitative Analysis: exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

- ➩

Reduce data dimensionality and extract latent motivational factors.

- ➩

Identify two dominant constructs: tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging.

- ➩

Method: EFA with Varimax rotation and Factor Extraction.

- ➩

Model Specification and structural equation modeling (SEM).

- ➩

Formalize the measurement model: Χᵢ = λ1F1 + λ2F2 + εᵢ.

- ➩

Test structural relationships: Y = βX + ζ.

- ➩

Assess the impact of latent factors on willingness to engage in tourism initiatives.

- ➩

Method: SEM (measurement and Structural Model Validation).

- ➩

Qualitative Phase: Stakeholder Validation in Fruška Gora.

- ➩

Conduct semi-structured interviews with 31 rural tourism stakeholders.

- ➩

Explore the perceptions of tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging in the Fruška Gora context.

- ➩

Identify potential adaptations for the model’s local applicability.

- ➩

Method: semi-structured interviews and Thematic Analysis.

- ➩

Epistemological Foundations.

- ➩

Adopt a constructivist epistemology emphasizing the co-production of knowledge, community agency, and place-based development values.

- ➩

Method: Reflexive Methodology and Participatory Research Principles.

Bregenzerwald, Austria: A Benchmark for Sustainable Rural Tourism Development

The Bregenzerwald region in Austria offers a compelling model for sustainable rural tourism development, particularly emphasizing the importance of community-led rural tourism development. Situated in a mountainous Alpine setting, Bregenzerwald encompasses 23 small villages characterized by their strong connection to the landscape and a deep-rooted cultural heritage [

68]. Nature-based tourism serves as a cornerstone of the local economy, with a well-developed focus on hiking, biking, skiing, and wellness activities that are deeply integrated into the surrounding environment [

69]. Cultural heritage in Bregenzerwald plays an equally significant role. The region is renowned for its mastery of woodcraft, traditional Alpine architecture, and artisanal cheese production, all of which have been meticulously preserved and innovatively adapted to contemporary needs. Crucially, the approach to sustainable tourism in Bregenzerwald is community-led, with local stakeholders actively shaping eco-tourism initiatives, promoting sustainable architecture, and preserving cultural landscapes [

70]. This model of community-led rural tourism development has been instrumental in ensuring that tourism enhances, rather than erodes, the region’s unique identity and social fabric. Local products, particularly cheese, wood products, and natural cosmetics, serve as key elements of Bregenzerwald’s tourism offering, reinforcing the connection between visitors and the region’s natural and cultural assets. Importantly, the overarching tourism goal in Bregenzerwald is to attract quality tourism rather than mass tourism, prioritizing the preservation of the landscape and local traditions over short-term economic gain.

Comparatively, regions such as Fruška Gora, Serbia, which are characterized by villages and small towns surrounding a low mountain range, show promising parallels. Like Bregenzerwald, Fruška Gora boasts a strong foundation in nature-based tourism through hiking, monasteries, and wine routes, as well as a rich cultural heritage rooted in Orthodox monastic networks, traditional crafts, and winemaking [

10]. While sustainable tourism efforts are still emerging in Fruška Gora—particularly in the domains of eco-tourism, agritourism, and rural revitalization—the potential for development aligned with community-led rural tourism development is significant. The developed tourism sector also contributes to the development and competitiveness of the region [

71]. Smolović [

72] underlines that it is necessary to include rural tourism in regional initiatives. Fruška Gora’s local products, including wine, honey, fruit preserves, and herbs, offer similar opportunities for promoting regional distinctiveness [

73]. To achieve a tourism model akin to Bregenzerwald’s, strategic efforts must focus on empowering local stakeholders and preserving cultural and natural values while promoting high-quality, sustainable tourism. In this sense, Bregenzerwald stands as an exemplary benchmark for other rural destinations aiming to balance tourism growth with the conservation of their environmental and cultural heritage through community-led rural tourism development.

4. Results

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.920, indicating an excellent level of common variance among the variables (

Table 1). Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (χ

2 = 7583.072, df = 66,

p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix and that the variables were suitable for factor analysis.

The initial factor analysis (see

Table 2) yielded a model that categorizes the variables into two factors, collectively accounting for 84.655% of the variance. Upon examining

Table 2, it is evident that the eigenvalue exceeds 1 for two factors, thereby demonstrating that the extracted factors are both adequate and sufficient. The number of factors was determined using the Kaiser criterion (retaining components with eigenvalues greater than 1), which is a widely accepted method for factor retention. To enhance interpretability, a Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization was applied, which aims to maximize the variance of factor loadings across variables and clarify the factor structure. The isolated factors are: F1. tourism empowerment and F2. sustainable belonging.

The first factor (

Table 3), tourism empowerment, encompasses a set of motivations primarily related to the economic and socio-cultural benefits derived from tourism activities. The residents recognize tourism as a catalyst for regional prosperity, job creation, and local economic empowerment. They highlight the importance of tourism in cultural valorization by promoting local crafts and culinary traditions, income diversification, enhancing overall life quality, and serving as a benchmark for sustainable rural growth. The recognition of heritage balance further emphasizes a strong community awareness of the need to harmonize modernization with cultural preservation. This confirms the sub-hypothesis H1a that higher levels of perceived tourism empowerment among residents positively influence their willingness to engage in community-led sustainable tourism development.

The second factor (

Table 3), sustainable belonging, captures the community’s preference for tourism which strengthens environmental consciousness and social cohesion. The residents express clear support for eco-friendly tourism practices, highlighting activities such as hiking and cycling that minimize environmental impact. Moreover, tourism is perceived as a medium for fostering community connectivity, enhancing interpersonal relationships among residents and visitors alike, and promoting a sense of global connectivity, allowing the residents to engage with broader cultural contexts while maintaining local identity. This confirms the sub-hypothesis H1b that a stronger sense of sustainable belonging among residents positively influences their support for eco-friendly and socially cohesive tourism initiatives. These findings suggest that the Bregenzerwald community views tourism not merely as an economic tool, but as a holistic development mechanism that strengthens economic resilience, promotes environmental stewardship, and deepens social cohesion. The model reflects a mature and sustainable approach to rural tourism, positioning the local community as an active agent in shaping tourism development according to their values and long-term interests.

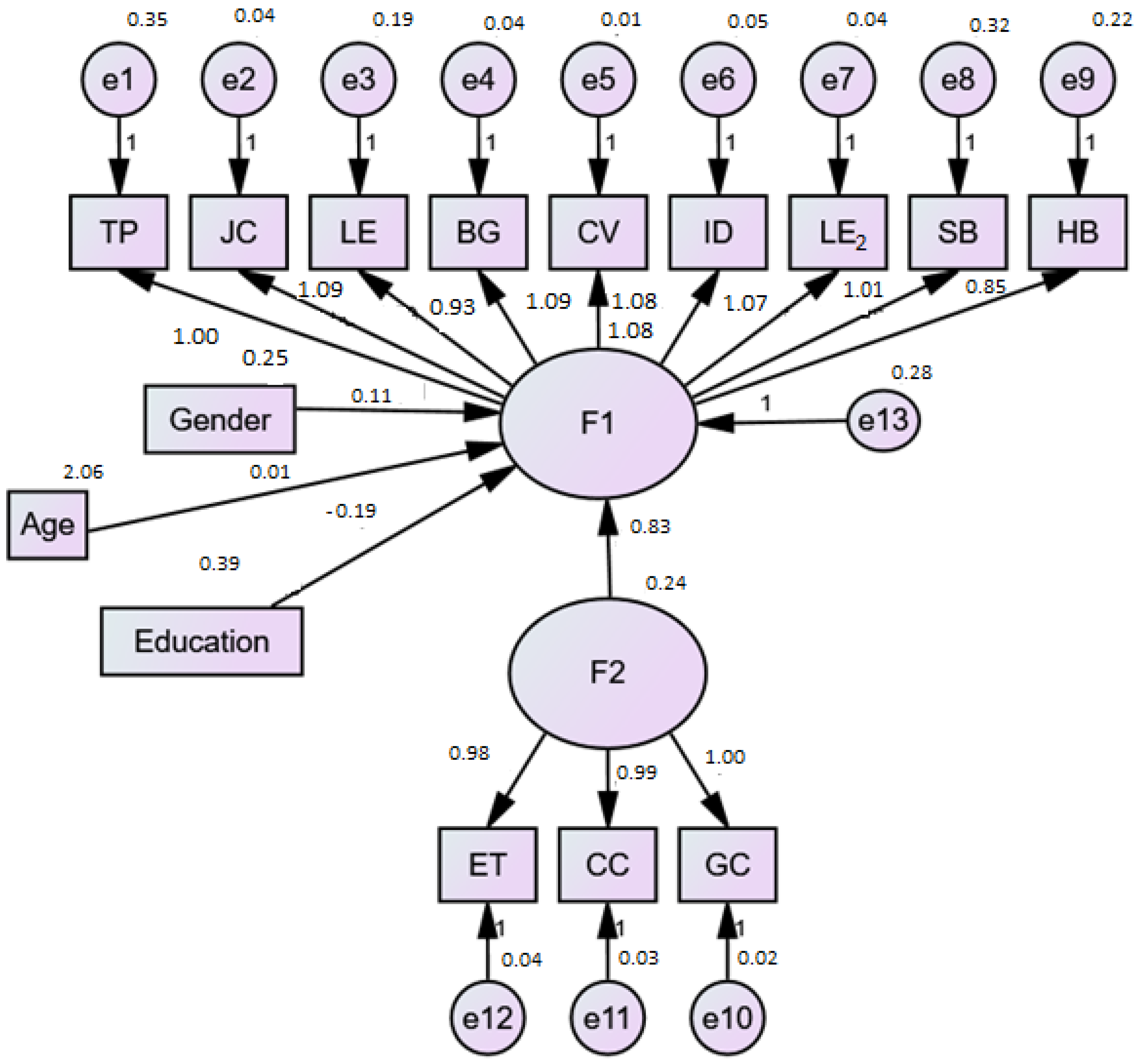

The structural equation modeling (

Figure 1) results indicate that the latent construct tourism empowerment (F1)—operationalized through indicators such as tourism prosperity, job creation, life enhancement, business growth, cultural valorization, income diversification, sustainable benchmark, and heritage balance—has a strong positive effect on the second latent construct, sustainable belonging (F2) (standardized path coefficient β = 0.83,

p < 0.001). This suggests that individuals who perceive tourism as a driver of local prosperity, economic growth, and cultural valorization are more likely to associate rural tourism with broader community and global sustainability goals. Regarding the influence of demographic variables on tourism empowerment (F1), gender exhibits a small positive effect (β = 0.11), implying that gender differences slightly influence how individuals perceive the benefits of tourism empowerment, with one gender (depending on coding) marginally more favorable. Age shows a negligible influence (β = 0.01), suggesting that perceptions of tourism empowerment are relatively stable across different age groups within the sample. Interestingly, education exerts a negative effect on perceptions of tourism empowerment (β = −0.19), meaning that individuals with higher levels of formal education tend to perceive the empowering effects of tourism development slightly less positively. This could imply that more educated individuals adopt a more critical or cautious perspective toward tourism-led development, possibly due to the greater awareness of its potential risks (e.g., cultural commodification, environmental degradation, and economic dependency) alongside its benefits. All the model fit indices indicate an acceptable fit of the model to the data. The RMSEA value of 0.073, within the recommended range of 0.050 to 0.080, suggests a good fit. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.968), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.944), and Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI = 0.907) all exceed the commonly accepted threshold of 0.90, further supporting the model’s adequacy. Additionally, the SRMR value of 0.04 falls below the recommended cutoff of 0.04, indicating a satisfactory residual-based fit.

All the observed indicators load strongly onto their respective latent variables, with standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.85 to 1.09 for F1 and from 0.98 to 1.00 for F2, supporting the convergent validity of the constructs. The relatively low measurement error variances further indicate good model fit and internal consistency across the measured items. The findings support a conceptualization of rural tourism development as a process that, when perceived positively in terms of empowerment outcomes, fosters a broader sense of belonging both locally and globally. However, these perceptions are modestly conditioned by individual socio-demographic characteristics, particularly education level.

The standardized regression weights (

Table 4) show the strength of the relationships between the latent constructs (F1 and F2), socio-demographic predictors (gender, age, and education), and observed indicators. The analysis demonstrates that the socio-economic and cultural impacts of tourism (F1) exert a strong positive influence on tourism connectivity outcomes (F2), with a standardized coefficient of 0.596 (

Table 3). This finding suggests that enhancements in factors such as tourism prosperity, local empowerment, business growth, cultural valorization, income diversification, and life enhancement substantially contribute to strengthening eco-friendly tourism practices, fostering stronger community ties, and promoting greater global connectivity. In other words, as the positive impacts of tourism on local economies and cultures grow, so too does the capacity of destinations to integrate sustainable and globally connected tourism practices.

The relationship between F1 and gender was found to be very weak and positive (β = 0.079), indicating that gender has minimal influence on individuals’ perceptions of the socio-economic and cultural impacts of tourism. This suggests that both male and female respondents perceive the benefits of tourism similarly, and gender differences do not significantly alter the evaluation of tourism’s broader impacts. Similarly, the relationship between F1 and age was almost negligible (β = 0.018), implying that perceptions of tourism’s socio-economic and cultural contributions are consistent across different age groups. Age does not appear to be a determining factor in shaping attitudes toward the benefits derived from tourism development. In contrast, education showed a small to moderate positive relationship with F1 (β = 0.172). This result indicates that individuals with higher levels of education are somewhat more likely to recognize and value the socio-economic and cultural benefits of tourism. Education may play a role in enhancing awareness and understanding of tourism’s multifaceted contributions to local development, cultural preservation, and economic diversification.

The analysis of indicator loadings provides deeper insight into the composition and explanatory power of the latent constructs F1 (socio-economic and cultural tourism impacts) and F2 (connectivity outcomes). For construct F1, the following observed variables exhibited the highest loadings: cultural valorization (0.995), job creation (0.964), life enhancement (0.967), income diversification (0.958), and local empowerment (0.822). These results indicate that the central dimensions underlying socio-economic and cultural tourism impacts are strongly associated with tourism’s ability to preserve and promote local culture, generate employment opportunities, enhance the overall quality of life, diversify income sources within communities, and empower local populations. The extremely high standardized loadings suggest that these dimensions are particularly salient and critical in defining the latent factor F1. In addition to the highest loadings, several indicators displayed moderately high contributions: sustainable benchmark (0.773), heritage balance (0.776), and tourism prosperity (0.755). While slightly lower than the top indicators, these loadings remain very strong and emphasize the importance of sustainability, the balance between development and heritage conservation, and the overall economic prosperity generated by tourism. These aspects, though secondary to the primary indicators, are, nevertheless, significant components of the broader socio-economic and cultural impacts construct.

Regarding the construct F2 (connectivity outcomes), all the observed indicators demonstrated very high loadings: eco-friendly tourism (0.953), community connectivity (0.947), and global connectivity (0.922). The exceptionally strong loadings suggest that the latent factor F2 is robustly explained by these three dimensions. Eco-friendly tourism practices, the strengthening of local community ties, and the facilitation of global networks are thus integral to conceptualizing tourism connectivity outcomes. These results highlight the centrality of sustainable environmental practices and both local and international linkages in the formation of a connected and resilient tourism sector.

After identifying representative factors, the results of the previous research were used to form research in the Fruška Gora area. By answering these questions, the research contributes to the field of rural tourism development, offering a comparative approach and proposing a model for sustainable growth that can be replicated or adapted in other rural settings across Europe.

Factor 1—Tourism Empowerment (

Table 5): This factor represents stakeholders’ belief in tourism as a means of economic development, livelihood diversification, and local capacity building. The interviewees consistently emphasized that tourism facilitates economic prosperity by attracting new customer bases and increasing demand for local products and services. The business owners, farmers, and artisans identified tourism as a crucial enabler of income generation and business expansion, with tourism-related consumption patterns fostering new economic niches such as crafts, organic produce, and experiential gastronomy. In terms of job creation, government officials expect tourism to contribute across multiple sectors, including hospitality, transport, retail, and cultural services. This aligns with broader rural development narratives that see tourism as a tool for reducing unemployment and demographic decline in peripheral areas. The respondents also associated tourism with local empowerment, particularly for marginalized groups such as small-scale farmers and traditional artisans. Tourism offers these actors an avenue to assert their cultural identity and achieve economic self-sufficiency, aligning with participatory development models. Tourism was viewed as a mechanism for cultural valorization, enhancing the visibility and appreciation of local traditions, crafts, and cuisine. The stakeholders stressed that tourism supports both the preservation and evolution of cultural practices, provided that engagement remains authentic and community-led. The perceived improvements to quality of life—including better infrastructure, healthcare access, and local services—further reinforce the empowering potential of tourism. There is also an aspirational element: many stakeholders envision their village becoming a benchmark for sustainable rural tourism, one that balances economic vitality with heritage preservation. Finally, concerns about heritage balance reflect a nuanced understanding of the need for culturally sensitive development. Stakeholders advocated for building design and planning that respects traditional aesthetics and uses local materials, underscoring their commitment to sustainable placemaking.

Factor 2—Sustainable Belonging (

Table 6): This second factor focuses on the social and ecological functions of tourism. The stakeholders highlighted the importance of eco-friendly tourism practices, including hiking, cycling, and nature walks, as environmentally low-impact alternatives that showcase the region’s natural assets. These preferences reflect a growing alignment with climate-conscious tourism and reinforce the need for green infrastructure and soft mobility solutions in rural destinations. Tourism also plays a significant role in fostering community connectivity. Shared events, educational programs, and local initiatives were seen as opportunities to strengthen social ties and stimulate intergenerational engagement, especially involving youth in heritage and environmental education. These forms of social participation contribute to increased cohesion and a sense of collective ownership over tourism development. The theme of global connectivity emerged as the stakeholders acknowledged tourism’s potential to link the village with international networks. This outward orientation not only opens new markets but also introduces opportunities for cultural exchange and cooperative promotion, helping to position the village globally without compromising local identity. Taken together, the two factors indicate a sophisticated, multidimensional understanding of tourism among the local stakeholders. Tourism is perceived not only as a means of economic empowerment but also as a strategy for social resilience, ecological stewardship, and cultural sustainability. This positions Bregenzerwald as a model for rural tourism, where local values and global trends converge to foster inclusive and sustainable community development. This confirms the sub-hypothesis H1c that the conceptual framework of rural tourism development based on the dimensions of

tourism empowerment and

sustainable belonging, as identified in Bregenzerwald, is recognized and positively received by the stakeholders in Fruška Gora, indicating its potential applicability as a model of best practice.

The research confirms that the conceptual framework of rural tourism development, based on the dimensions of tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging originally identified in the Bregenzerwald model, is positively recognized and applicable to the context of Fruška Gora. The stakeholders in Fruška Gora emphasized tourism’s role as a catalyst for economic prosperity, livelihood diversification, job creation, and cultural valorization, aligning with the principles of tourism empowerment. At the same time, they demonstrated a strong awareness of tourism’s social and ecological functions, advocating for eco-friendly practices, community connectivity, and global engagement, which reflects the dimension of sustainable belonging. Together, these findings highlight a sophisticated and multidimensional understanding of tourism among local stakeholders, where tourism is not only seen as an economic driver but also as a means to strengthen social resilience, preserve cultural identity, and promote environmental stewardship. By adopting the Bregenzerwald model, Fruška Gora can position itself as a leading example of sustainable rural tourism development, balancing local values with global sustainability trends to foster inclusive, resilient, and culturally sensitive growth.

5. Discussion

The findings from the Bregenzerwald case study and their subsequent validation in the Fruška Gora context offer compelling evidence for the importance of integrating both tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging into rural tourism development strategies. These two constructs not only reveal how residents perceive the impacts of tourism, but also directly shape their willingness to actively participate in and support rural tourism initiatives. Tourism empowerment reflects residents’ recognition of the tangible benefits derived from tourism, including economic growth, job creation, business development, and cultural preservation. When residents perceive tourism as a catalyst for improving livelihoods and community resilience, they are more likely to support, advocate for, and invest time and resources in tourism-related projects. This empowerment is particularly salient in rural regions where alternative economic opportunities are limited, making tourism a strategic tool for inclusive development and poverty alleviation. Moreover, the significance placed on heritage balance reveals that residents value development that respects and preserves local traditions—this encourages community-led tourism, where locals take ownership and play active roles in shaping the tourism offer. On the other hand, sustainable belonging emphasizes residents’ desire for tourism that aligns with environmental ethics and social cohesion. The high loadings of eco-friendly tourism and community connectivity suggest that tourism is not just an economic endeavor but also a social and ecological one. When tourism fosters stronger community ties and respects natural resources, residents are more inclined to engage in tourism activities that reflect their values. This engagement is driven by a sense of collective identity, whereby tourism becomes a means of intergenerational learning, cultural exchange, and global-local integration. Together, these constructs indicate that local willingness to participate in rural tourism is multidimensional—motivated by both practical outcomes and deeper cultural and ecological values. Residents do not passively accept tourism; rather, they critically assess its contributions to their economic well-being, social fabric, and environmental integrity.

These findings have broader implications for rural areas beyond Bregenzerwald and Fruška Gora. First, they underscore the importance of tailoring tourism policies to local perceptions and values. Rural communities are not homogeneous, and their motivations for supporting tourism differ based on socio-cultural, economic, and environmental contexts. Policymakers and tourism planners should engage residents early in the development process and foster participatory governance models that empower local voices. Second, the replicability of the tourism empowerment–sustainable belonging framework suggests its utility as a diagnostic and planning tool. It can help identify areas where community support may be strong (e.g., cultural valorization or eco-tourism) and where it may require capacity building (e.g., business training or sustainable infrastructure investment). Applying this model across different European rural contexts may also support benchmarking efforts, enabling cross-regional learning and the exchange of best practices. Finally, the nuanced relationship between education and tourism perceptions offers insights into awareness-raising and communication strategies. More educated individuals may view tourism with caution, highlighting the need for transparent impact assessments and balanced narratives that acknowledge both benefits and risks. This is crucial for maintaining trust and ensuring that tourism development does not alienate key segments of the community. In sum, by understanding and leveraging the dual dynamics of empowerment and belonging, rural destinations can foster a more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable tourism sector—one that not only brings economic benefits but also strengthens the social and environmental fabric of rural life.

The insights derived from the Bregenzerwald case align with global best practices in rural tourism development that emphasize community empowerment, sustainability, and participatory governance. Comparative examples from regions with similar socio-economic and cultural characteristics further validate the applicability of the tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging framework. A notable parallel can be drawn with South Tyrol, Italy, where the integration of agriculture, hospitality, and local identity has led to a highly successful farm-based tourism model. According to Grillini et al., [

74], South Tyrol’s approach—grounded in family-run accommodations, short food supply chains, and a strong emphasis on cultural landscape preservation—demonstrates how tourism can thrive when locals are the owners and storytellers of the experience [

75]. Much like Bregenzerwald, the region leverages traditional knowledge and alpine heritage, fostering both economic resilience and cultural continuity. Similarly, the Engadine Valley in Switzerland offers another example where tourism is deeply rooted in community cooperation and sustainability principles. There, locals actively participate in shaping the tourism offer, and the region has implemented robust policies to maintain ecological balance, encourage multi-generational entrepreneurship, and promote regional branding based on authenticity [

76]. In Austria’s Wachau Valley, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the successful blend of wine tourism, landscape conservation, and local empowerment illustrates how small-scale tourism operations can be scaled without compromising cultural and environmental values [

77]. Wachau’s commitment to preserving architectural heritage and traditional winemaking reflects similar values found in Bregenzerwald—namely, the belief that tourism should complement rather than compete with local ways of life. These international cases affirm that rural tourism success hinges on resident agency, context-specific development, and a balance between innovation and tradition. They also reveal the scalability of the tourism empowerment and sustainable belonging framework to other rural regions in Europe and beyond. For rural areas in transition—such as those in the Western Balkans or Central and Eastern Europe—these models provide actionable pathways for fostering inclusive rural tourism that respects both people and place.

Challenges and Considerations for Cross-Regional Transferability of the Bregenzerwald Model

While the Bregenzerwald model demonstrates a compelling example of community-driven, sustainable rural tourism development, its transferability to other regions must be approached with caution. Several critical challenges can arise when attempting to implement such a model across different regional contexts, including policy disparities, resource accessibility, market visibility, and socio-cultural readiness. One of the foremost challenges in transferring rural tourism models lies in differences in governance structures and policy frameworks. The Bregenzerwald region benefits from Austria’s strong tradition of local governance and clear inter-municipal cooperation, which enables the efficient planning and implementation of rural development initiatives. However, in regions such as rural Romania or Bulgaria, the institutional landscape is often fragmented, with overlapping jurisdictions and limited coordination between local and regional authorities. As highlighted by Navarro et al., [

78], the uneven implementation of EU rural development instruments like LEADER in these areas has resulted in reduced efficiency and weaker community participation, thereby hindering similar bottom-up initiatives. Another significant barrier lies in the ability to effectively promote rural destinations in competitive tourism markets. According to Turčinović et al., [

10] Tuscany has successfully leveraged coordinated regional branding, notably through the “Vivi Toscana” campaign, to unify its diverse rural offerings under a recognizable identity. This contrasts with lesser-known rural destinations in the Western Balkans, such as parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina or North Macedonia, where fragmented marketing strategies and limited digital presence have kept these regions off the radar of international tourists [

79]. In such cases, replicating the visibility and branding success of the Bregenzerwald model would require substantial investment in promotional infrastructure and stakeholder coordination.

Resource inequality, particularly in terms of financial support and technical infrastructure, is another critical concern. In South Tyrol, Italy, public–private partnerships and EU funding streams have facilitated the integration of digital tools, green infrastructure, and farm-based hospitality upgrades [

75]. By contrast, many rural hosts in Serbia, including those in Fruška Gora, report difficulties in accessing sustainable financing and technical support. Challenges include bureaucratic obstacles in grant applications, limited banking services tailored for smallholders, and a lack of technical training in digital and sustainable practices [

10]. Such disparities must be addressed before the Bregenzerwald model can be effectively adapted to these regions. A model like Bregenzerwald’s relies heavily on active community participation and trust among local stakeholders. In regions with a history of strong civic engagement, such as rural Wales—where projects in Snowdonia National Park have thrived due to deep-rooted community pride—residents are more likely to support collective tourism strategies [

80]. Conversely, in many parts of the Western Balkans, including rural Serbia, long-standing mistrust in public institutions and weak participatory culture can impede the establishment of collaborative governance structures [

81]. Overcoming such socio-cultural barriers may require sustained community-building initiatives, transparency mechanisms, and trust-building programs.

Finally, the success of rural tourism models often depends on the quality of environmental management and supporting infrastructure. Bregenzerwald’s emphasis on ecological harmony and sustainable land use is facilitated by strict environmental policies and well-developed infrastructure. In contrast, many rural areas in Southeast Europe, including Fruška Gora, face infrastructural deficits such as poor waste management systems, inadequate public transportation, and underdeveloped eco-friendly lodging [

16]. According to REC Serbia [

82], such limitations can significantly hinder efforts to promote environmentally responsible tourism, a cornerstone of the Bregenzerwald approach. These examples demonstrate that while the Bregenzerwald model offers valuable insights into sustainable and community-centered rural tourism, its replication must be context-sensitive. Policymakers and local stakeholders should prioritize capacity-building, resource mobilization, and inclusive governance to adapt the model effectively. Rather than pursuing a direct transplant of practices, emphasis should be placed on the co-creation, local adaptation, and incremental integration of the model’s core principles, ensuring that they align with the unique socio-political and economic realities of each region.

6. Conclusions

The Bregenzerwald Model illustrates how rural regions can achieve sustainable development by integrating community participation, cultural preservation, and environmental responsibility. Rooted in the Austrian region of Bregenzerwald, this model demonstrates the potential of empowering local communities, supporting traditional crafts, and fostering eco-friendly tourism practices. This study confirms that residents’ motivation—especially through perceived tourism empowerment and a sense of sustainable belonging—is a key driver of community-led rural tourism development. Residents who feel empowered and connected to sustainability values are more likely to engage in and support eco-friendly, socially cohesive tourism initiatives. The successful application of this conceptual framework in Fruška Gora underscores its broader relevance for similar rural destinations. However, the study has several limitations. It is based on a single case application, which may limit generalizability. The sample size and geographic focus might not fully capture the diversity of rural tourism contexts. Moreover, while the conceptual dimensions were validated, the long-term impacts of their application remain to be studied. Future research should explore the longitudinal effects of empowerment and belonging on tourism outcomes in diverse rural regions. Comparative studies between Fruška Gora and other destinations applying similar models could offer deeper insights. In addition, exploring digital innovations in promoting sustainable rural tourism and assessing their role in community engagement could enhance the framework’s applicability. Ultimately, this study affirms that inclusive, culturally rooted, and environmentally responsible tourism—as embodied by the Bregenzerwald Model—provides a viable pathway for sustainable rural development.