The Health Cost of Rural Banquet Culture: The Mediating Role of Labor Time and Health Decision-Making—Evidence from Jiangsu, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Institutional Background and Theoretical Hypothesis

3.1. Banquet Culture and Its Governance in China

3.2. Theoretical Hypothesis

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Data Collection and Sample Representativeness

4.2. Defining Variables

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

4.2.2. Independent Variables

4.2.3. Mechanism Variables

4.2.4. Control Variables

4.3. Identification Strategies

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Baseline Results

5.2. Mechanism Analysis

5.3. Robustness Testing

5.3.1. Addressing Endogeneity

5.3.2. Variable Tests Replacement

5.3.3. Exclusion of Other Factors

5.3.4. Measurement Models Replacement

6. Extended Analysis

6.1. Heterogeneity Analysis

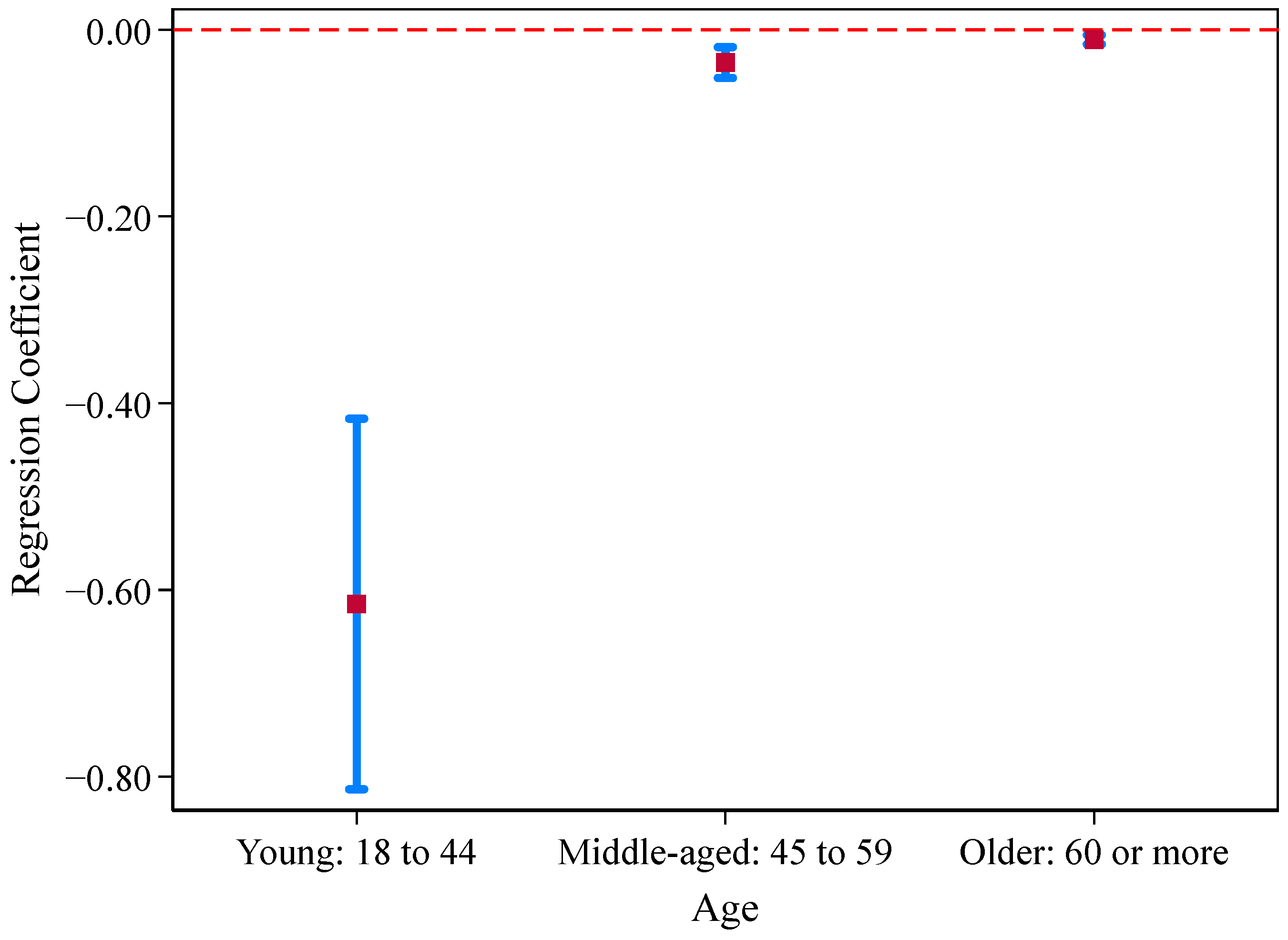

6.1.1. Different Age Groups

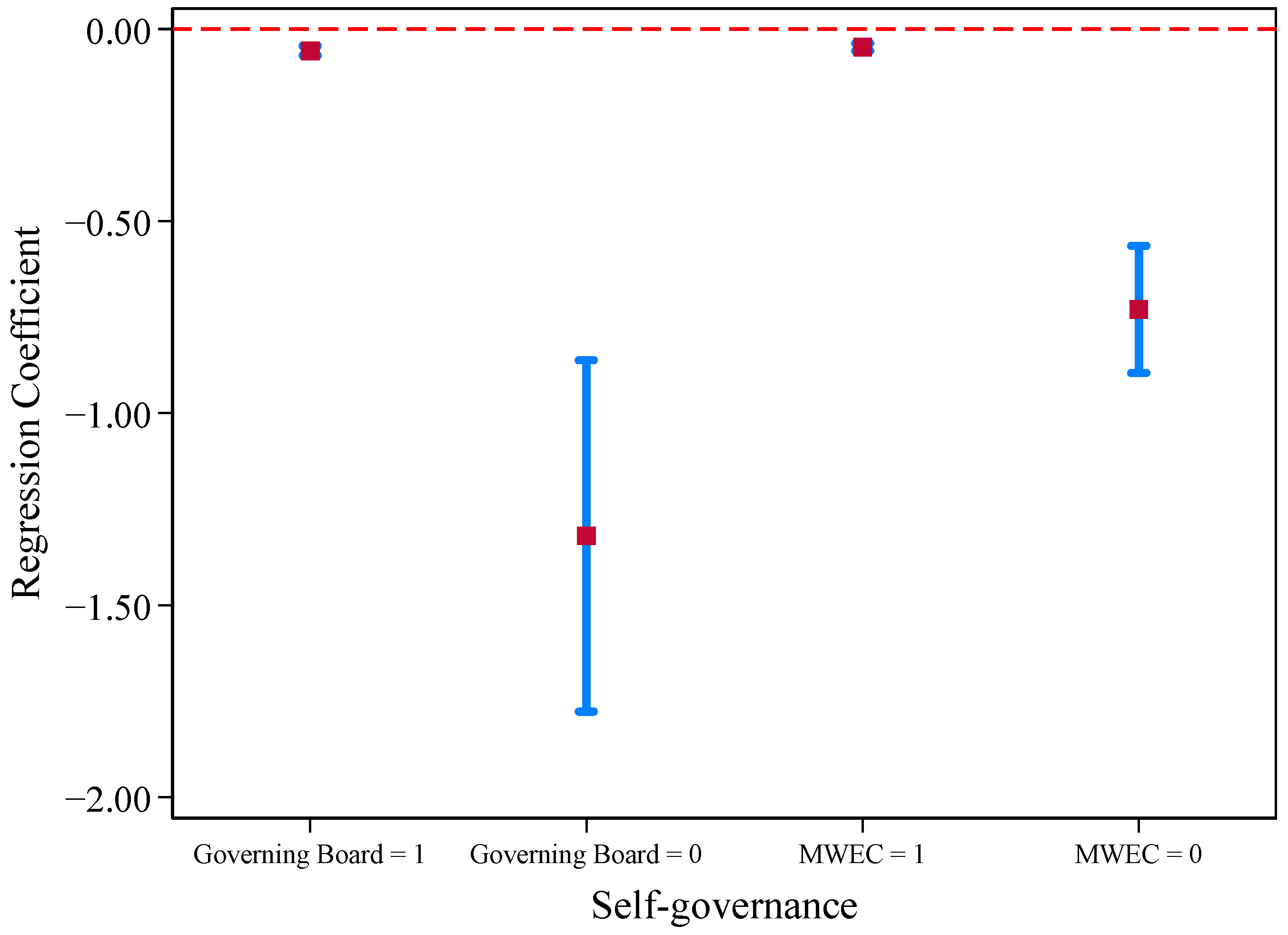

6.1.2. Impact of Self-Governance

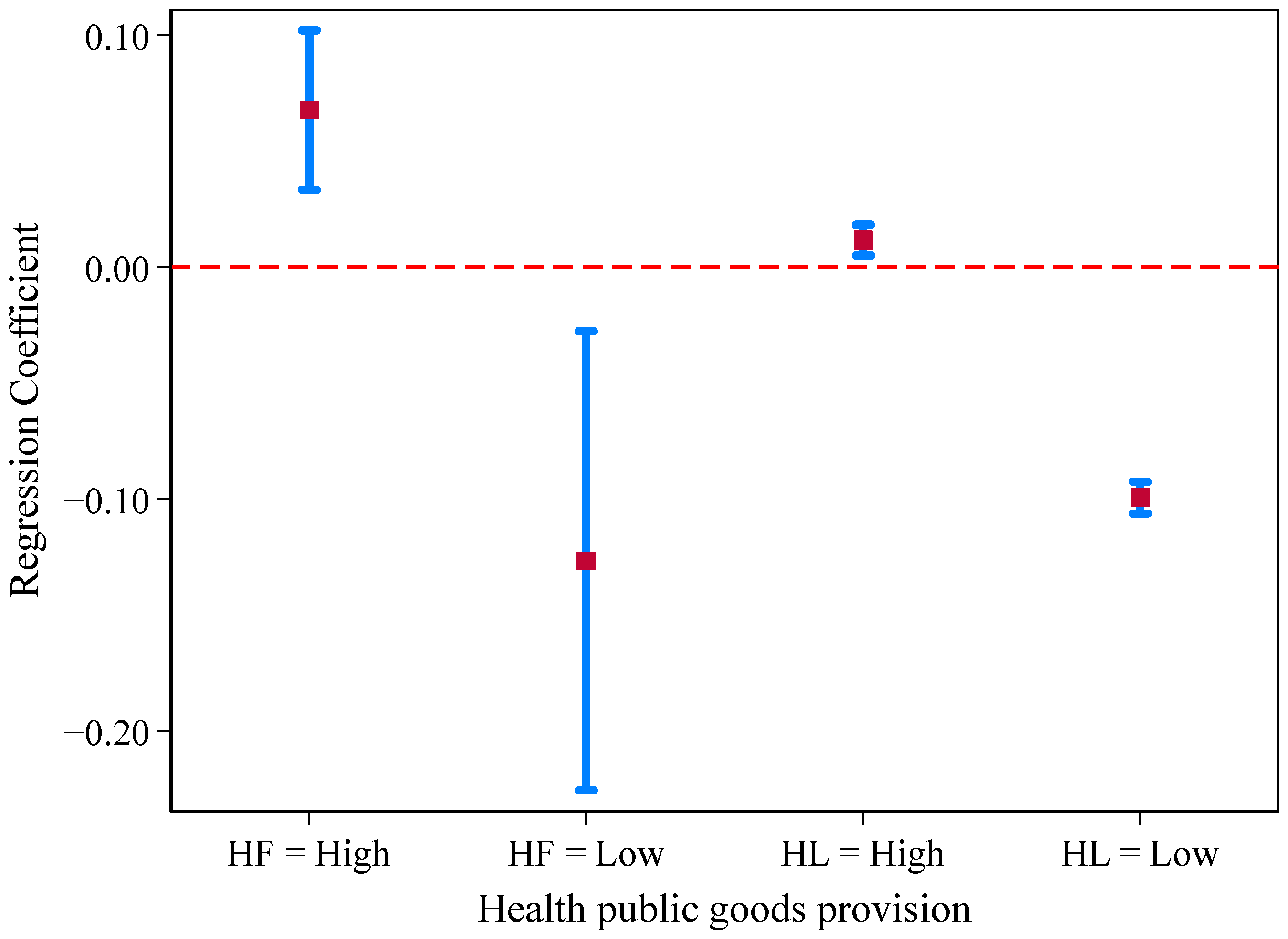

6.1.3. Health Public Facilities Supply

6.2. Further Tests of Health

7. Conclusions and Discussion

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Discussion

7.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NFWHs | Non-Farm Working Hours |

| TP | Time Preference |

| HI | Health Investment |

| Banqcul | Banquet culture |

Appendix A

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |

| Health | Self-identified Health Conditions: 1 = Incapacity to work; 2 = Poor; 3 = Medium; 4 = Good; 5 = Excellent. |

| Independent Variable | |

| Banquet Culture | Are the traditional wedding and funeral customs in your village complicated? 1 = Complicated; 2 = Moderate; 3 = Not Complicated; 4 = Indifferent. |

| Mechanism Variables | |

| Non-Farm Working Hours | Total volume of non-farm work within a year (days). |

| Household Income from Non-Farm Work | Total income from non-farm work of a year (CNY). |

| Time Preference | What are your time preferences? 1 = I only focus on the current income, regardless of the future; 2 = I value both current and future benefits; 3 = I only value future earnings, not the present. |

| Health Investment | Air purifier (piece); Water purifier (set). |

| Control Variables | |

| Individual Level | |

| Gender | Gender (1 = male; 0 = female). |

| Age | Age (In full years). |

| Years of Education | Educational level (Number of years in schooling). |

| Emotional Conditions | In the past week, I have been in low moods. 1 = Almost Not (less than one day); 2 = Sometimes (1–2 days); 3 = Frequent (3–4 days); 4 = Most of the time (5–7 days). |

| Social Relations | The number of people who you can borrow CNY 50,000 from when you are in trouble. |

| Recent Medical Visit Situation | Have you gone to the hospital for your last illness or injury? 1 = Yes; 0 = No. |

| Household Level | |

| Family Size | How many people are there in your permanent population (Living for 6 months or more throughout a year)? |

| Family Income | Total household income (yuan); Natural logarithm processing. |

| Type of Housing | What is your current housing type? 1 = Reinforced concrete structure; 2 = Masonry-concrete structure; 3 = Brick, stone and wood houses; 4 = Other, please specify. |

| Living Space | What is the living space of your house (m2)? |

| Medical Insurance | Do all members of your family have medical insurance? 1 = Yes; 0 = No. |

| Drinking Water Conditions | How do you get your drinking water? 1 = Indoor tap water; 2 = Tap water in the yard; 3 = Well water in the yard; 4 = Mineral water; 5 = Other, please specify. |

| Living Conditions | Water Heaters (Number); Air conditioning (Number); Washing Machines (Number). |

| Village Level | |

| Village Elevation | Altitude of the village committee location. |

| Population Density | Population density (person/acre). |

| Economic Level | Per capita net income of the whole village. |

| Drinking Water Safety | Is there a drinking water safety project in this village? 1 = Yes; 0 = No. |

| Sanitation Facilities | Number of trash cans in the village. |

| Medical Quality | Number of practicing (assistant) physicians. |

| Tool Variables | |

| Number of Traditional Villages in the County | The number of traditional villages in the county to which the village belongs. |

| Others | |

| Village Level | Annual number of civil disputes. Annual number of public security violations. |

References

- Chapman, A.R. The social determinants of health, health equity, and human rights. Health Hum. Rights 2010, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M. Fair society, healthy lives. In Inequalities in Health: Concepts, Measures, and Ethics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Friel, S.; Marmot, M.G. Action on the social determinants of health and health inequities goes global. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health 2011, 32, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.-X. The Flow of Gifts: Reciprocity and Social Networks in a Chinese Village; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, S. Social norms and their influence on eating behaviours. Appetite 2015, 86, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, C.P.; Roth, D.A.; Polivy, J. Effects of the presence of others on food intake: A normative interpretation. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvy, S.-J.; Jarrin, D.; Paluch, R.; Irfan, N.; Pliner, P. Effects of social influence on eating in couples, friends and strangers. Appetite 2007, 49, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Cheng, S. Food waste and influencing factors in event-related consumptions: Taking wedding banquet as an example. Prog. Geogr. 2020, 39, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheil-Adlung, X. Global Evidence on Inequities in Rural Health Protection: New Data on Rural Deficits in Health Coverage for 174 Countries; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Henning-Smith, C. Improving Health Among Rural Residents in the US. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021, 325, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.; Williamson, P.; Kulu, H. Unravelling urban-rural health disparities in England. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Brems, C.; Warner, T.D.; Roberts, L.W. Rural-urban health care provider disparities in Alaska and New Mexico. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2006, 33, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosby, A.G.; Neaves, T.T.; Cossman, R.E.; Cossman, J.S.; James, W.L.; Feierabend, N.; Mirvis, D.M.; Jones, C.A.; Farrigan, T. Preliminary evidence for an emerging nonmetropolitan mortality penalty in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1470–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.K.; Siahpush, M. Widening rural–urban disparities in all-cause mortality and mortality from major causes of death in the USA, 1969–2009. J. Urban Health 2014, 91, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulle, A. Rural health care and rural poverty-inextricably linked-policy in progress. HST Up-Date 1997, 28, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.K.; Daus, G.P.; Allender, M.; Ramey, C.T.; Martin, E.K.; Perry, C.; Andrew, A.; Vedamuthu, I.P. Social determinants of health in the United States: Addressing major health inequality trends for the nation, 1935–2016. Int. J. MCH AIDS 2017, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemble, S.K.; Westbrook, A.; Lynfield, R.; Bogard, A.; Koktavy, N.; Gall, K.; Lappi, V.; DeVries, A.S.; Kaplan, E.; Smith, K.E. Foodborne Outbreak of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Associated with a High School Dance Team Banquet-Minnesota, 2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein-Zamir, C.; Tallen-Gozani, E.; Abramson, N.; Shoob, H.; Yishai, R.; Agmon, V.; Reisfeld, A.; Valinsky, L.; Marva, E. Salmonella enterica Outbreak in a Banqueting Hall in Jerusalem: The Unseen Hand of the Epidemiological Ttriangle? Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2009, 11, 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.E.; Osterholm, M.T.; Mariotti, J.A.; Korlath, J.A.; Lawrence, D.H.; Ristinen, T.L.; Greenberg, H.B. A foodborne outbreak of Norwalk virus gastroenteritis. Evidence for post-recovery transmission. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1986, 124, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Health capital provision and human capital accumulation. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2020, 72, 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. The elementary forms of religious life. In Social Theory Re-Wired; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies; Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, J.P.; Bloch, M. Money and the Morality of Exchange; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.B.; Humphreys, J.S.; Wilson, M.G. Addressing the health disadvantage of rural populations: How does epidemiological evidence inform rural health policies and research? Aust. J. Rural. Health 2008, 16, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Kawachi, I.; Glymour, M.M. Social Epidemiology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R.G. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D.; Karas Montez, J. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S54–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, S.; Ruddock, H. Social influences on eating. In Handbook of Eating and Drinking: Interdisciplinary Perspectives; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Dietler, M.; Hayden, B. Theorizing the feast: Rituals of consumption, commensal politics, and power in African contexts. In Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2001; pp. 65–114. [Google Scholar]

- Confins. The 1900 mayors’ banquet. Confins-Revue Franco-Bresilienne De Geographie-Revista Franco-Brasileira De Geografia. Confins 2023, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupke, J. Communal interaction and societal structure: The pleasures of dining and dinner companions in ancient Rome. Saeculum 1998, 49, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, H. Domestic Goddesses: Maternity, Globalization and Middle-Class Identity in Contemporary India; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, L.S. Improvised songs of praise and group sociality in contemporary Chinese banquet culture. Int. Commun. Chin. Cult. 2020, 7, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmüller, H. Communities of Complicity: Everyday Ethics in Rural China; Berghahn Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfeld, E. Bitter and Sweet: Food, Meaning, and Modernity in Rural China; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 63. [Google Scholar]

- Kipnis, A.B. Producing Guanxi: Sentiment, Self, and Subculture in a North China Village; Duke University Press: Durham, NA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.; Zhang, Y.W.; Ruan, S.Z. Ritualized Relational Work: Secret Banquets and Rural Cadres in China. Crit. Asian Stud. 2024, 56, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.C. Gao Village Revisited: The Life of Rural People in Contemporary China; The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press: Hong Kong, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nee, V.; Ingram, P. Embeddedness and Beyond: Institutions, Exchange and Social Structure; Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies, Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- George, B.; Baekgaard, M.; Decramer, A.; Audenaert, M.; Goeminne, S. Institutional isomorphism, negativity bias and performance information use by politicians: A survey experiment. Public Adm. 2020, 98, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.L. Chinese kinship reconsidered: Anthropological perspectives on historical research. China Q. 1982, 92, 589–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Aljoudi, A.S.; Al-Mazam, A.; Choudhry, A.J. Outbreak of food borne Salmonella among guests of a wedding ceremony: The role of cultural factors. J. Fam. Community Med. 2010, 17, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandy, S.; Leakhann, S.; Phalmony, H.; Denny, J.; Roces, M.C. Vibrio parahaemolyticus enteritis outbreak following a wedding banquet in a rural village–Kampong Speu, Cambodia, April 2012. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. WPSAR 2012, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houldcroft, L.; Haycraft, E.; Farrow, C. Peer and friend influences on children’s eating. Soc. Dev. 2014, 23, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakusheva, O.; Kapinos, K.A.; Eisenberg, D. Estimating heterogeneous and hierarchical peer effects on body weight using roommate assignments as a natural experiment. J. Hum. Resour. 2014, 49, 234–261. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, J.M.; Brewer, E.M. The amount eaten in meals by humans is a power function of the number of people present. Physiol. Behav. 1992, 51, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Mao, Y. Hospitality and ritual: A discursive study of toasting in Chinese dining contexts. Discourse Stud. 2024, 27, 14614456241277415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokdad, A.H.; Marks, J.S.; Stroup, D.F.; Gerberding, J.L. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004, 291, 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Yin, N.; Zhao, Y. Socioeconomic status and chronic diseases: The case of hypertension in China. China Econ. Rev. 2012, 23, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakidou, E.; Afshin, A.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abera, S.F.; Aboyans, V. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1345–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheper-Hughes, N.; Lock, M.M. The mindful body: A prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Med. Anthropol. Q. 1987, 1, 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.C.; Sheldon, O.J. Relaxing Moral Reasoning to Win: How Organizational Identification Relates to Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carsten, J. The substance of kinship and the heat of the hearth: Feeding, personhood, and relatedness among Malays in Pulau Langkawi. Am. Ethnol. 1995, 22, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. The influence of income on health: Views of an epidemiologist. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzeval, M.; Judge, K. Income and health: The time dimension. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 1371–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Ma, G. Does gift expenditure reduce normal consumption: Evidence from CFPS 2010. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2015, 3, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mushkin, S.J. Health as an Investment. J. Political Econ. 1962, 70, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luce, B.R.; Mauskopf, J.; Sloan, F.A.; Ostermann, J.; Paramore, L.C. The return on investment in health care: From 1980 to 2000. Value Health 2006, 9, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-K.; Cheng, K.-C.; Tetteh, A.O.; Hildemann, L.M.; Nadeau, K.C. Effectiveness of air purifier on health outcomes and indoor particles in homes of children with allergic diseases in Fresno, California: A pilot study. J. Asthma 2017, 54, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Sobsey, M.D.; Loomis, D. Local drinking water filters reduce diarrheal disease in Cambodia: A randomized, controlled trial of the ceramic water purifier. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 79, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Where in China Is the Most “Sumptuous” Banquet? These 4 Provinces are on the List, See If There Is Your Hometown? Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/812454472_120892525 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Su, W.W.; Liu, J.K.; Wen, J.; Liang, J.J.; Liang, J.H.; Dai, Y.; Fu, P.; Ma, J.; Guo, Y.C.; Liu, Z.T. Analysis of rural banquet foodborne disease outbreaks in China from 2010 to 2020. Zhongguo Shipin Weisheng Zazhi 2023, 35, 915–921. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Gastro-Politics in Hindu South Asia. Am. Ethnol. 1981, 8, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, F.; Rao, V.; Desai, S. Wedding celebrations as conspicuous consumption: Signaling social status in rural India. J. Hum. Resour. 2004, 39, 675–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.K.; Duan, X.J.; Wang, L. Spatial-Temporal Patterns and Driving Factors of Rapid Urban Land Development in Provincial China: A Case Study of Jiangsu. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ye, Q. The impact of digital governance on the health of rural residents: The mediating role of governance efficiency and access to information. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1419629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfeld, E. The moral registers of banqueting in contemporary China. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2019, 48, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, S.; Gunasekara, S.; Baddock, K.; Clarke, L. Time for healthy investment. New Zealand Med. J. 2017, 130, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fishburn, P.C.; Rubinstein, A. Time Preference. Int. Econ. Rev. 1982, 23, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.; Harrison, G.W.; Lau, M.I.; Rutström, E.E. Eliciting risk and time preferences. Econometrica 2008, 76, 583–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevy, Y. Time consistency: Stationarity and time invariance. Econometrica 2015, 83, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haushofer, J.; Fehr, E. On the psychology of poverty. Science 2014, 344, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, J. Before dinner: The health value of gaseous fuels. Energy Policy 2024, 185, 113935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapie, M.; Galdos-Balzategui, A.; Freitas, B.L.S.; Reygadas, F.; Sabogal-Paz, L.P.; Pichel, N.; Botero, L.; Montoya, L.J.; Galeano, L.; Carvajal, G.; et al. Automated household-based water disinfection system for rural communities: Field trials and community appropriation. Water Res. 2025, 284, 123888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Zhu, T.; Liang, S.; Ezzati, M.; Remais, J.V. Environmental health in China: Progress towards clean air and safe water. Lancet 2010, 375, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liao, H. Energy poverty and solid fuels use in rural China: Analysis based on national population census. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2014, 23, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. The impact of water quality on health: Evidence from the drinking water infrastructure program in rural China. J. Health Econ. 2012, 31, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehfuess, E.; Mehta, S.; Prüss-Üstün, A. Assessing household solid fuel use: Multiple implications for the Millennium Development Goals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anenberg, S. Clean stoves benefit climate and health. Nature 2012, 490, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.J.; Glass, R.I.; Balbus, J.M.; Collins, F.S. A major environmental cause of death. Science 2011, 334, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangyo, E. The effect of water accessibility on child health in China. J. Health Econ. 2008, 27, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, M.; Leino, J.; Miguel, E.; Zwane, A.P. Spring cleaning: Rural water impacts, valuation, and property rights institutions. Q. J. Econ. 2011, 126, 145–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiani, S.; Gertler, P.; Schargrodsky, E. Water for life: The impact of the privatization of water services on child mortality. J. Political Econ. 2005, 113, 83–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, X. The long-term economic impact of water quality: Evidence from rural drinking water program in China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 94, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, H.; Behrman, J.R.; Lavy, V.; Menon, R. Child health and school enrollment: A longitudinal analysis. J. Hum. Resour. 2001, 36, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhar, B.; Skini, M.; Shamohammadi, M.; Ghaffaripour, J.; Nilchian, F. The effectiveness of home water purification systems on the amount of fluoride in drinking water. J. Dent. 2015, 16, 278. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Cao, M.; Tong, D.; Finkelstein, Z.; Hoek, E.M. A critical review of point-of-use drinking water treatment in the United States. NPJ Clean Water 2021, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Lee, S.C.; Moon, S.; Choe, E.; Shin, H.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, H.H.; Huh, D.; Park, J.-W. Effects of air purifiers on patients with allergic rhinitis: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, C.L.; Borçoi, A.R.; Almança, C.C.J.; Barbosa, W.M.; Archanjo, A.B.; de Assis Pinheiro, J.; Freitas, F.V.; de Oliveira, D.R.; Cardoso, L.D.; De Paula, H. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among rural residents from remote areas. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, Z.; Hu, G. Impact of the new rural social pension insurance on the health of the rural older adult population: Based on the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1310180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriola, K.J.; Merken, T.M.; Bigger, L.; Haardörfer, R.; Hermstad, A.; Owolabi, S.; Daniel, J.; Kegler, M. Understanding the relationship between social capital, health, and well-being in a southern rural population. J. Rural Health 2024, 40, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. JPSP 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athey, S.; Tibshirani, J.; Wager, S. Generalized random forests. Ann. Stat. 2019, 47, 1148–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbmacher, H.; Huber, M.; Lafférs, L.; Langen, H.; Spindler, M. Causal mediation analysis with double machine learning. Econom. J. 2022, 25, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Demirer, M.; Duflo, E.; Hansen, C.; Newey, W.; Robins, J. Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters. Econom. J. 2018, 21, C1–C68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.K.; Dahiya, K.; Sharma, A. Problem formulations and solvers in linear SVM: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Were, K.; Bui, D.T.; Dick, O.B.; Singh, B.R. A comparative assessment of support vector regression, artificial neural networks, and random forests for predicting and mapping soil organic carbon stocks across an Afromontane landscape. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Hamilton, G.G.; Zheng, W. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.H.; Wright, N.; Xiao, D.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Du, H.D.; Yang, L.; Millwood, I.Y.; Pei, P.; Wang, J.Z.; et al. Tobacco smoking and risks of more than 470 diseases in China: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, E1014–E1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumgay, H.; Shield, K.; Charvat, H.; Ferrari, P.; Sornpaisarn, B.; Obot, I.; Islami, F.; Lemmens, V.; Rehm, J.; Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.N.; Chen, H.Y.; Hao, Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Song, X.J.; Mok, T.M. The dynamic relationship between environmental pollution, economic development and public health: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinchaisri, W.P.; Jensen, S.T. Community vibrancy and its relationship with safety in Philadelphia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.B. Human Territorial Functioning: An Empirical, Evolutionary Perspective on Individual and Small Group Territorial Cognitions, Behaviors, and Consequences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Windows, B. The Police and Neighborhood Safety. Atl. Mon. 1982, 249, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Nanetti, R.Y.; Leonardi, R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, L.T.; Hillier, A.; Chau-Glendinning, H.; Subramanian, S.; Williams, D.R.; Kawachi, I. Can you party your way to better health? A propensity score analysis of block parties and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 138, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. Soc. Epidemiol. 2000, 174, 290–319. [Google Scholar]

- Szreter, S.; Woolcock, M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 33, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable | N | Mean | p50 | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Health | 2420 | 4.049 | 4.000 | 1.055 | 1.000 | 5.000 |

| Independent variable | Banquet culture | 2420 | 2.881 | 2.857 | 0.192 | 2.417 | 3.313 |

| Mechanism variables | Non-farm working hours | 2352 | 73.580 | 0.000 | 118.600 | 0.000 | 365.000 |

| Household income from non-farm work | 2420 | 7.954 | 10.400 | 4.629 | 0.000 | 14.670 | |

| Time preference | 2340 | 1.701 | 2.000 | 0.685 | 1.000 | 3.000 | |

| Health investments | 2413 | 0.370 | 0.000 | 0.765 | 0.000 | 13.000 | |

| Individual level control variable | Genders | 2417 | 0.727 | 1.000 | 0.446 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 2420 | 62.160 | 64.000 | 11.430 | 18.000 | 92.000 | |

| Years of schooling | 2420 | 7.184 | 8.000 | 3.971 | 0.000 | 19.000 | |

| Emotional state | 2419 | 1.210 | 1.000 | 0.521 | 1.000 | 4.000 | |

| Social relation | 2357 | 5.604 | 2.000 | 18.570 | 0.000 | 500.000 | |

| Recent medical treatment | 2404 | 0.775 | 1.000 | 0.417 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Family level control variable | Household size | 2420 | 3.044 | 2.000 | 1.601 | 0.000 | 11.000 |

| Log of household income | 2420 | 7.537 | 8.896 | 3.707 | 0.000 | 14.930 | |

| Housing type | 2418 | 1.798 | 2.000 | 0.765 | 1.000 | 12.000 | |

| Housing area | 2392 | 205.200 | 200.000 | 118.800 | 15.000 | 1500.000 | |

| Medical insurance | 2387 | 0.941 | 1.000 | 0.235 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Drinking water conditions | 2417 | 1.877 | 1.000 | 25.340 | 1.000 | 1234.000 | |

| Living conditions | 2415 | 1.114 | 1.000 | 0.770 | 0.000 | 22.000 | |

| 2416 | 2.342 | 2.000 | 1.824 | 0.000 | 30.000 | ||

| 2413 | 1.184 | 1.000 | 0.821 | 0.000 | 30.000 | ||

| Village level control variable | Village elevation | 2038 | 11.420 | 10.000 | 11.050 | 0.000 | 50.000 |

| Population density | 2420 | 0.524 | 0.497 | 0.406 | 0.000 | 2.918 | |

| Level of village economy | 2384 | 9.958 | 10.080 | 0.582 | 7.765 | 10.820 | |

| Drinking water security | 2343 | 0.696 | 1.000 | 0.460 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Sanitation facilities | 2343 | 509.800 | 146.000 | 870.200 | 2.650 | 4636.000 | |

| Medical level | 2420 | 1.042 | 0.000 | 1.435 | 0.000 | 7.000 |

| Variables | Health | Health | Health | Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Banqcul | −5.1186 *** (0.0638) | −4.9387 *** (0.1593) | −5.6797 *** (0.2314) | −0.3556 *** (0.0534) |

| Individual Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Household Controls | Yes | Yes | ||

| Village Controls | Yes | |||

| Village FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Log-likelihood | −3017.1907 | −2771.8203 | −2647.5977 | −2259.4591 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0385 | 0.0925 | 0.1053 | 0.1015 |

| Obs | 2420 | 2354 | 2277 | 1913 |

| Variables | Health | NFWH | Health | INFW | Health | TP | Health | HI | Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

| Banqcul | −0.4179 *** (0.0436) | −89.8524 *** (5.1054) | −0.3432 *** (0.0548) | −3.1743 *** (0.2450) | −0.3651 *** (0.0515) | −0.6100 *** (0.0334) | −0.3808 *** (0.0529) | −0.1191 *** (0.0310) | −0.3871 *** (0.0427) |

| NFWH | 0.0008 *** (0.0002) | ||||||||

| INFW | 0.0166 *** (0.0067) | ||||||||

| TP | 0.0876 *** (0.312) | ||||||||

| HI | 0.0643 *** (0.0225) | ||||||||

| All Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Village FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2254 | 0.2586 | 0.2313 | 0.1925 | 0.2294 | 0.1146 | 0.2279 | 0.2056 | 0.2280 |

| Obs | 1913 | 1860 | 1860 | 1913 | 1913 | 1855 | 1855 | 1911 | 1911 |

| Variables | DML | DML-IV | DML-IV (Changing Algorithms) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Parametric | First Stage | Second Stage | First Stage | Second Stage | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Banqcul | −0.4093 *** (0.0109) | −6.0045 *** (1.4025) | −6.2962 ** (2.7583) | ||

| IV_Tradvill | 0.0089 *** (0.0010) | 0.0565 *** (0.0192) | |||

| All Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Village FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kleibergen–Paap Wald rk F statistic | 72.6100 | ||||

| Anderson–Rubin Wald test | 51.0600 *** | 72.2100 | |||

| Obs | 1913 | 1913 | 1913 | 1913 | 1913 |

| Variables | Healthfam | Health | Health | Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Banqcul | −0.4056 *** (0.4328) | −0.2905 *** (0.0758) | −0.4930 *** (0.0923) | |

| Banqcul_binary | −0.1621 *** (0.0243) | |||

| Tobacco | Yes | |||

| Alcohol | Yes | |||

| Environmental Pollution | Yes | |||

| All Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Village FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2293 | 0.1015 | 0.1037 | 0.1044 |

| Obs | 1913 | 1913 | 1892 | 1913 |

| Variables | Annual Civil Disputes | Public Security Violations (Annual) |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Banqcul | 6.3960 (38.2419) | 0.4017 (2.4222) |

| All Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0735 | 0.0581 |

| Obs | 1874 | 1823 |

| Variables | Popmor | Infantmor | Longevity | Mhealth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Banqcul | 3.2215 *** (0.5807) | 1.3162 *** (0.2168) | −1.8989 ** (0.7976) | 0.0239 (0.0309) |

| All Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1888 | 0.1792 | 0.1441 | 0.3647 |

| Obs | 1864 | 1735 | 1816 | 1913 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R. The Health Cost of Rural Banquet Culture: The Mediating Role of Labor Time and Health Decision-Making—Evidence from Jiangsu, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125318

Zhang Y, Chen Y, Xu R. The Health Cost of Rural Banquet Culture: The Mediating Role of Labor Time and Health Decision-Making—Evidence from Jiangsu, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125318

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuanyuan, Yongzhou Chen, and Rong Xu. 2025. "The Health Cost of Rural Banquet Culture: The Mediating Role of Labor Time and Health Decision-Making—Evidence from Jiangsu, China" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125318

APA StyleZhang, Y., Chen, Y., & Xu, R. (2025). The Health Cost of Rural Banquet Culture: The Mediating Role of Labor Time and Health Decision-Making—Evidence from Jiangsu, China. Sustainability, 17(12), 5318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125318