Legal Loopholes and Investment Pressure in the Development of Individual Recreational Buildings in Protected Landscapes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Loss of pastures [7] e.g., disappearance of grazing animals; increase in meadows;

- Habitat rehabilitation sites, e.g., increase in semi-natural vegetation and wetlands;

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

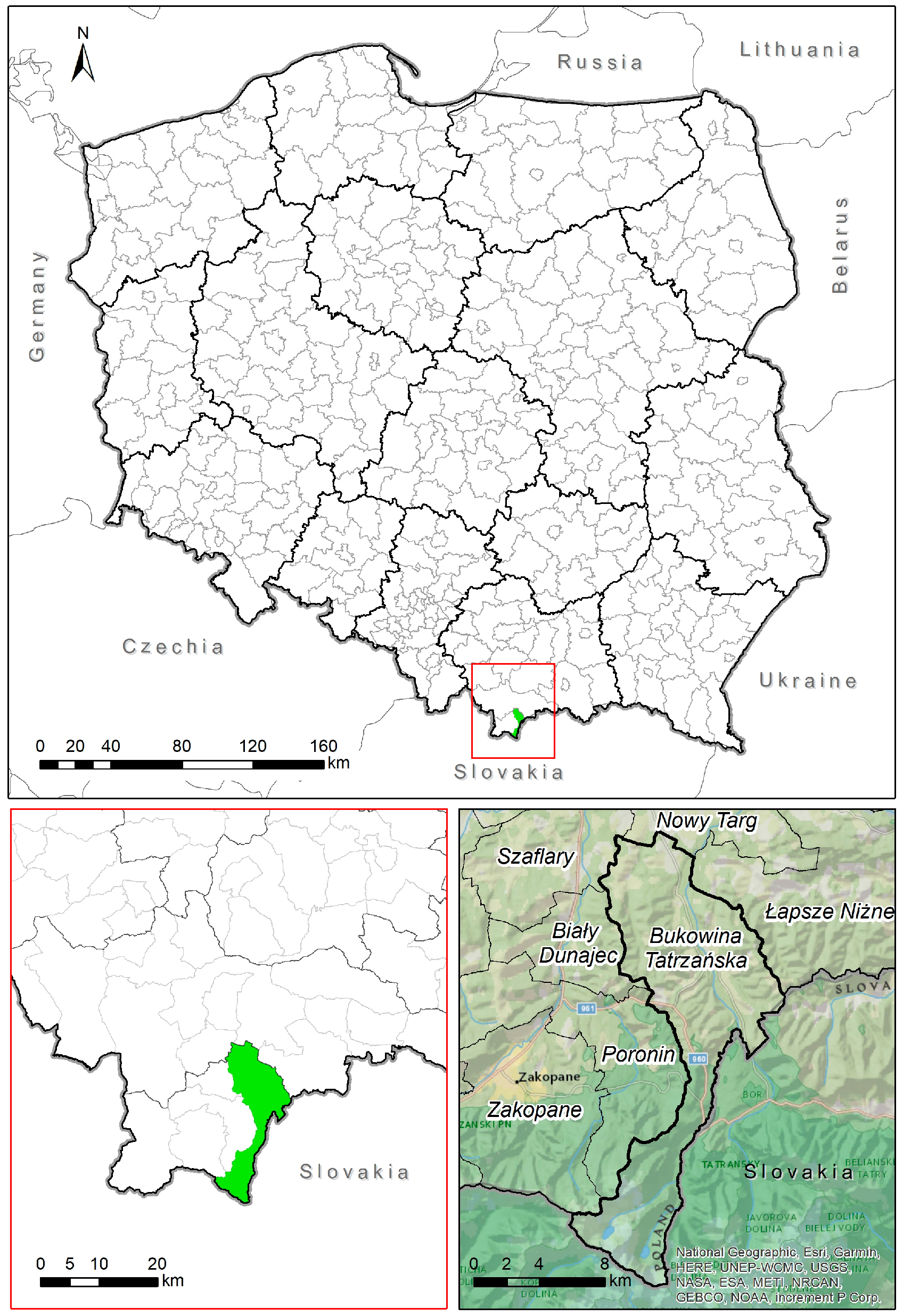

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methedology of the Study and Data Collection

- 1.

- What is the scale of individual recreational buildings constructed without municipal approval, despite the refusal to issue zoning decisions?

- 2.

- What impact do individual recreational buildings constructed in areas subject to development bans have on the natural environment and landscape?

- 3.

- Are individual recreational investments still being implemented without the consent of local authorities?

- A review of the relevant literature and formulation of the research objective;

- Identification of the scale of decisions refusing to issue zoning conditions for individual recreational investments (based on data from the Bukowina Tatrzańska Municipal Office);

- Determination of the development status of properties for which zoning decisions for individual recreational buildings were refused (field inspection within the municipality of Bukowina Tatrzańska);

- Analysis of local spatial policy provisions for developments implemented without municipal approval;

- Assessment of the consequences resulting from the construction of individual recreational buildings in conflict with local spatial planning policies;

- Formulation of answers to the research questions;

- Development of conclusions and recommendations.

3.3. Legal Basis for the Realization of Individual Recreation Buildings

4. Results

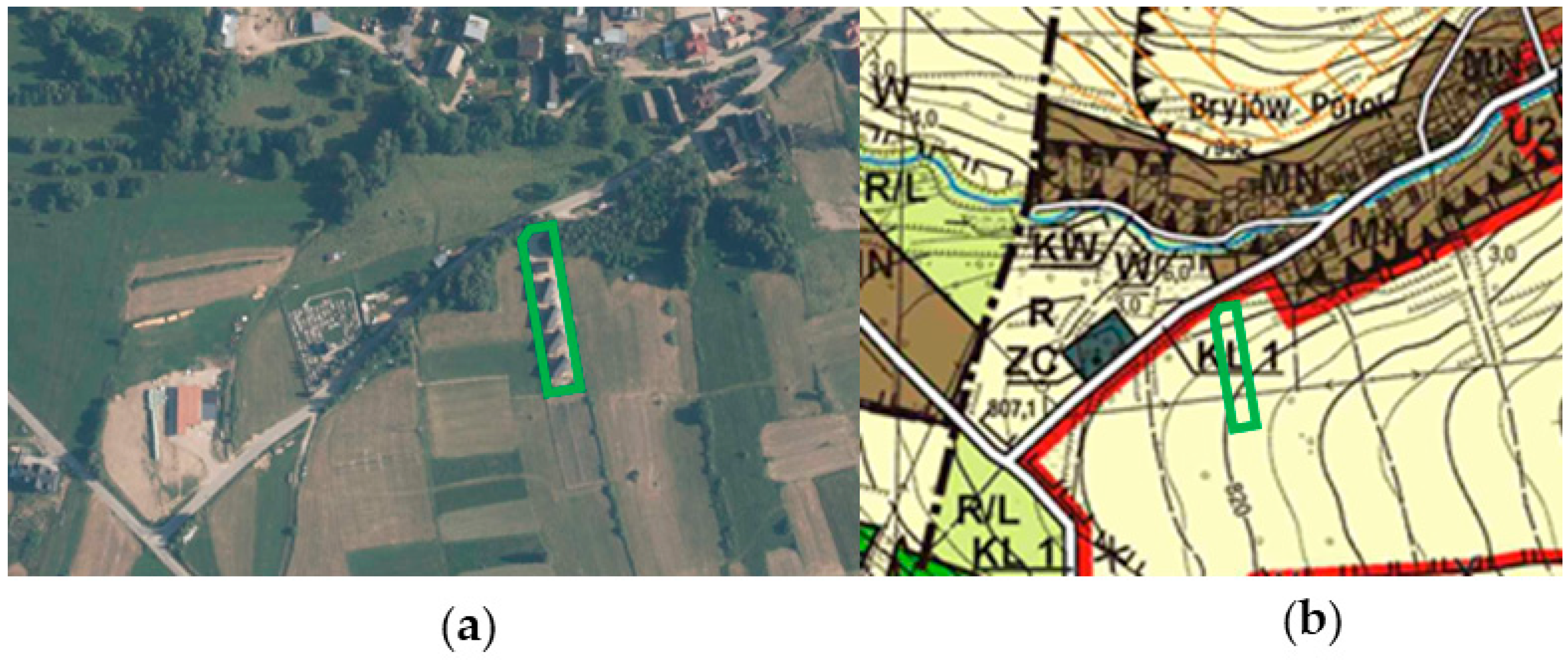

4.1. Realization of an Investment After a Decision Refusing to Determine the Zoning Conditions Was Issued

- Prohibit the location of cubature constructions (except for the upper stations of ski lifts and funicular railways);

- Prohibit the location of new overhead technical infrastructure lines and equipment;

- Prohibit the location of advertising;

- Prohibit the introduction of high greenery;

- Prohibit to change the landform [33].

4.2. The Realization of Modular Buildings

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Regarding the scale of individual recreational buildings constructed without municipal approval, this study confirmed numerous cases of such developments carried out despite formal refusals to issue zoning decisions. Field inspections in villages such as Leśnica and Rzepiska revealed that investors proceeded with construction under the notification procedure, effectively bypassing the municipality’s authority. This demonstrates a systemic loophole in the current legal framework (Question 1).

- The environmental and landscape impacts of these developments are considerable. The buildings are often located in ecologically sensitive areas, such as protected landscape zones and scenic exposures, where construction is normally restricted. Their presence contributes to spatial disorder, landscape fragmentation, and the erosion of cultural identity, especially due to architectural inconsistency with regional traditions. The cumulative effect of such developments threatens biodiversity and the visual integrity of the natural environment (Question 2).

- This study finds that such unauthorized recreational developments are ongoing, indicating an urgent need for reform. The phenomenon persists because the notification-based system lacks adequate oversight and enforcement mechanisms. Investors continue to exploit legal ambiguities, especially in areas not covered by local development plans, which currently make up a significant portion of the municipality (Question 3).

- 1.

- Strengthening the role of local development plans in the municipality by covering larger areas of the municipality with the local plans in force to eliminate the possibility of erecting individual recreation buildings in the areas subject to a ban on development and implementing detailed regulations and rules for development and land use.

- 2.

- Revision of the Construction Law—imposing stricter requirements for construction notifications and tightening regulations on the realization of investments without a local development plan.

- 3.

- Increasing control over the realization of investments—implementing more effective mechanisms to supervise compliance with the Construction Law and local development plans.

- 4.

- Considering the introduction of diversified measures and principles for shaping spatial order that take into account the protection of landscapes presenting natural and cultural value.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szlachetko, K.; Szlachetko, J.H. Planowanie i Zagospodarowanie Przestrzenne. Komentarz; Wolters Kluwer: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Act of 27 March 2003 on Spatial Planning and Development (Consolidated Text: Journal of Laws of 2024, Item 1130). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20030800717/U/D20030717Lj.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Woźniak, M. Ład Przestrzenny Jako Paradygmat Zrównoważonego Gospodarowania Przestrzenią [Spatial Order as a Paradigm of Sustainable Space]. Białostockie Stud. Prawnicze 2015, 18, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszeja, E.; Szczepańska, M.; Gałecka-Drozda, A.; de Mezer, E.; Wilkaniec, A. Ochrona i kształtowanie krajobrazu kulturowego w zintegrowanym planowaniu rozwoju [Protection and Shaping of the Cultural Landscape in Integrated Development Planning]. Seria Zintegrowane Planowanie Rozwoju. Wydział Geografii Społeczno-Ekonomicznej i Gospodarki Przestrzennej Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznań, 2022. Available online: https://wgseigp.amu.edu.pl/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/394103/ochrona-i-ksztaltowanie-krajobrazu-kulturowego-w-zintegrowanym-planowaniu-rozwoju.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Bőhm, A. Proponowane działania. [Proposed Actions]. Czas. Tech. 2008, z. 1-A, 137–146. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/34386/file/suwFiles/BohmA_ProponowaneDzialania.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Sallay, A.; Jombach, S.; Filepne Kovács, K. Landschanges and function lost landscape values. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2012, 10, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feranec, J.; Jaffrain, G.; Soukup, T.; Hazeu, G. Determining changes and flows inEuropean landscapes 1990–2000 using CORINE land cover data. Appl. Geogr. 2010, 30, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Schulp, C.J.E.; Witte, N.; Veldkamp, A. Downscaling of land usechange scenarios to assess the dynamics of European landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 114, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, M. The spontaneous reafforestation in abandoned agricultural lands:perception and aesthetic assessment by locals and tourists. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 31, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasanta, T.; Laguna, M.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M. Do tourism-based ski resortscontribute to the homogeneous development of the Mediterranean mountains? A casestudy in the Central Spanish Pyrenees. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caletrío, J. Tourism, landscape change and critical thresholds. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 38, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.; Prieler, S.; van Velthuizen, H.; Berndes, G.; Faaij, A.; Londo, M.; de Wit, M. Biofuel production potentials in Europe: Sustainable use of cultivated land andpastures, Part II: Land use scenarios. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Landscape Change and the Urbanization Process in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 67, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keken, Z.; Kušta, T.; Langer, P.; Skaloš, J. Landscape structural changes between 1950 and 2012 and their role in wildlife–vehicle collisions in the Czech Republic. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grădinaru, S.R.; Iojă, C.I.; Pătru-Stupariu, I.; Hersperger, A.M. Are Spatial Planning Objectives Reflected in the Evolution of Urban Landscape Patterns? A Framework for the Evaluation of Spatial Planning Outcomes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarnia, N.; Schwick, C.; Jaeger, J.A. Accelerated urban sprawl in Montreal, Quebec City, and Zurich: Investigating the differences using time series 1951–2011. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 1229–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, B.; Zullo, F.; Fiorini, L.; Marucci, A. Illegal building in Italy: Too complex a problem for national land policy? Cities 2021, 112, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, B.; de Biase, C. A typical Italian phenomenon. The unauthorized building. Int. J. Civ. Struct. Eng.–IJCSE 2015, 2, 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zanfi, F. The Città Abusiva in Contemporary Southern Italy: Illegal Building and Prospects for Change. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 3428–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šostak, O.R.; Kutut, V. Investigation into expansion of illegal construction in the National Park of Curonian Spit. Bus. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkšiene, V.; Dvorak, J. Performance Management In Protected Areas: Localizing Governance of the Curonian Spit National Park, Lithuania. Public Adm. Issues 2020, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskresenskaya, E.; Zhilskiy, N. Theoretical and practical aspects of unauthorized construction: The matter of legalization and demolition. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 371, 02052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 7 July 2023 Amending the Act on Spatial Planning and Development and Certain Other Acts (Journal of Laws of 2023, Item 1688). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20230001688/O/D20231688.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Różycka-Czas, R.; Czesak, B.; Cegielska, K. Towards Evaluation of Environmental Spatial Order of Natural Valuable Landscapes in Suburban Areas: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, E. Planowanie przestrzenne na poziomie lokalnym—Powiązanie teorii z praktyką [Spatial Planning at Local Level—Linking Theory and Practice]; Polska Akademia Nauk, Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju, TOM 15/207: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, L. Kształtowanie ładu przestrzennego jako zadanie badawcze geografii historycznej. Acta Univ. Lodziensis. Folia Geogr. Socio-Oeconomica 2016, 25, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mierzejewska, L. Zrównoważony rozwój miasta, wybrane sposoby pojmowania, koncepcje i modele [Sustainable development of a city: Selected theoretical frameworks, concepts and models], Problemy Rozwoju Miast. Kwart. Nauk. Inst. Rozw. Miast 2015, 3, 5–11. Available online: https://bazekon.uek.krakow.pl/171413931 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Mikołajczyk, M.; Raszka, B. Multidimensional Comparative Analysis as a Tool of Spatial Order Evaluation: A Case Study from Southwestern Poland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 3287–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Act of 7 July 1994—Construction Law (Consolidated Text: Journal of Laws of 2024, Item 725, as Amended). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19940890414/U/D19940414Lj.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Act of July 7, 1994 Construction Law (Consolidated Text: Journal of Laws of 2020, Item 1333). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200001333/U/D20201333Lj.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Formularz Danych Dla Obszaru Chronionego Krajobrazu [Data form for the Protected Landscape Area]. Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska. Available online: https://crfop.gdos.gov.pl/CRFOP/download/pdf/PL.ZIPOP.1393.OCHK.279.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Uchwała Nr XX/274/20 Sejmiku Województwa Małopolskiego z dnia 27 kwietnia 2020 r. w sprawie Południowomałopolskiego Obszaru Chronionego Krajobrazu (Dziennik Urzędowy Woj. Małopolskiego z dn. 22 maja 2020 r., poz. 3482) [The Protected Landscape Area Covers Attractive Landscapes; Resolution No. XX/274/20 of the Małopolskie Voivodship Parliament, 27 April 2020 (Journal of Laws of the Małopolskie Voivodship of 22 May 2020, no. 3482). Available online: https://edziennik.malopolska.uw.gov.pl/legalact/2020/3482/ (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Studium Uwarunkowań i Kierunków Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Gminy Bukowina Tatrzańska [The Study of Land Use Conditions and Directions in the Spatial Planning System of the Bukowina Tatrzańska Municipality], Uchwała Rady Gminy Bukowina Tatrzańska Nr XLII/352/2022 z dnia 25 Maja 2022 r. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://ugbukowinatatrzanska.pl/file/get/GMINA/Rada_Gminy/Uchwaly/2022/Za%25C5%2582%25C4%2585cznik%2520Nr%25205%2520do%2520zmiany%2520Studium.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwirlYCd6LCNAxXqxAIHHZNpAggQFnoECDMQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3GXDHSpmvmFVPrbsv8UPfV (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Myczkowski, Z. Program ochrony krajobrazu kulturowego Polski. Krajobrazy niezwykłe–krajobrazy ginące. In Krajobrazy Europy; Drapella-Hermansdorfer, A., Mycak, O., Surma, M., Eds.; Krajobraz Jako Wyraz Idei i Wartości; The program of protection of the cultural landscape of Poland. Extraordinary landscapes—Disappearing Landscapes; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2019; pp. 27–41. Available online: https://dbc.wroc.pl/Content/75728/Krajobrazy_Europy_Krajobraz_jako_wyraz_idei_i_wartosci_.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Dobkowska, B. Decyzja o warunkach zabudowy dla całej działki ewidencyjnej czy jej części? [Decision on development conditions for the entire cadastral plot or part of it?]. UWM Stud. Prawnoustr. 2022, 58, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; Markowski, T.; Bąkowski, P.; Lorens, P.; Blaszke, M.; Zachariasz, I.; Szlachetko, J.; Giedych, R.; Tomczak, A.A.; Brudnicki, J.; et al. Perspektywa Prawna i Urbanistyczna w Planowaniu Przestrzennym. Wybrane Zagadnienia [Legal and Urban Perspective in Spatial Planning. Selected Issues]; Polska Akademia Nauk, Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; Volume 13, p. 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P.; Nowak, M.; Sudra, P.; Załęczna, M.; Blaszke, M. Economic Consequences of Adopting Local Spatial Development Plans for the Spatial Management System: The Case of Poland. Land 2021, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barełkowski, R. Prawo—czynnik instrumentalizacji przestrzeni [w]. In Krajobrazy Europy; Drapella-Hermansdorfer, A., Mycak, O., Surma, M., Eds.; Krajobraz Jako Wyraz Idei i, Wartości; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2019; Available online: https://dbc.wroc.pl/Content/75728/Krajobrazy_Europy_Krajobraz_jako_wyraz_idei_i_wartosci_.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Hersperger, A.; Mueller, G.; Knöpfel, M.; Siegfried, A.; Kienast, F. Evaluating outcomes in planning: Indicators and reference values for Swiss landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 77, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M. Law enforcement on the issuance of construction permits violating spatial planning in Medan City. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 452, 012073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianto, R.; Cahyaningtyas, I. Administrative Law Enforcement against Urban Spatial Planning Based on the Spatial Planning Law. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res. 2021, 4, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, M.; Getimis, P.; Blotevogel, H.H. (Eds.) Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.J.; Mitrea, A.; Filepne Kovács, K.; Jürgenson, E.; Legutko-Kobus, P.; Petrișor, A.-I.; Simeonova, V.; Blaszke, M. Uncovering Spatial Planning Values through Law: Insights from Central East European Planning Systems, Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Polska Akademia Nauk. EUROPA XXI 2024, 47, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Storozheva, A.; Dadayan, E.; Letyagina, E. Unauthorized Building as an Object of Improper Civil Construction. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1079, 032075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prepared Draft Decisions Refusing to Issue a Zoning Decision, Including for a Construction Project Consisting of | Year and Number of Draft Decisions Refusing to Issue a Zoning Decision: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| construction of a single-family residential building | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||

| construction of two single-family residential buildings with accompanying infrastructure | 4 | ||||||

| construction of three single-family residential buildings with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | 1 | |||||

| construction of four single-family residential buildings with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | 1 | |||||

| construction of five single-family residential buildings with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| construction of six single-family residential buildings with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| construction of a single-family detached residential building, not more than two-story high, with a floor area of up to 70 m2 and with technical infrastructure | 1 | 2 | |||||

| construction of eight single-family residential buildings and a service building, a barbecue gazebo, a playground for children with the accompanying infrastructure and the necessary construction equipment | 1 | ||||||

| construction of an individual recreation building up to 35 m2 with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | ||||||

| construction of two individual recreation buildings with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | ||||||

| construction of ten individual recreation buildings with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | ||||||

| construction of a free-standing shed, a free-standing platform for technical maintenance of the fence in recreational development | 2 | ||||||

| construction of three service buildings (tourist accommodation) with accompanying infrastructure, including the construction of technical infrastructure installations and connections, and the construction of other necessary building facilities | 2 | ||||||

| construction of six service buildings for the purposes of tourism and leisure with accompanying infrastructure | 1 | ||||||

| change in the use of five individual recreation buildings to single-family residential buildings | 1 | 1 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hełdak, M.; Ogórka, K.; Raszka, B. Legal Loopholes and Investment Pressure in the Development of Individual Recreational Buildings in Protected Landscapes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104659

Hełdak M, Ogórka K, Raszka B. Legal Loopholes and Investment Pressure in the Development of Individual Recreational Buildings in Protected Landscapes. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104659

Chicago/Turabian StyleHełdak, Maria, Klaudia Ogórka, and Beata Raszka. 2025. "Legal Loopholes and Investment Pressure in the Development of Individual Recreational Buildings in Protected Landscapes" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104659

APA StyleHełdak, M., Ogórka, K., & Raszka, B. (2025). Legal Loopholes and Investment Pressure in the Development of Individual Recreational Buildings in Protected Landscapes. Sustainability, 17(10), 4659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104659