Responsibility Driving Innovation: How Environmentally Responsible Leadership Shapes Employee Green Creativity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

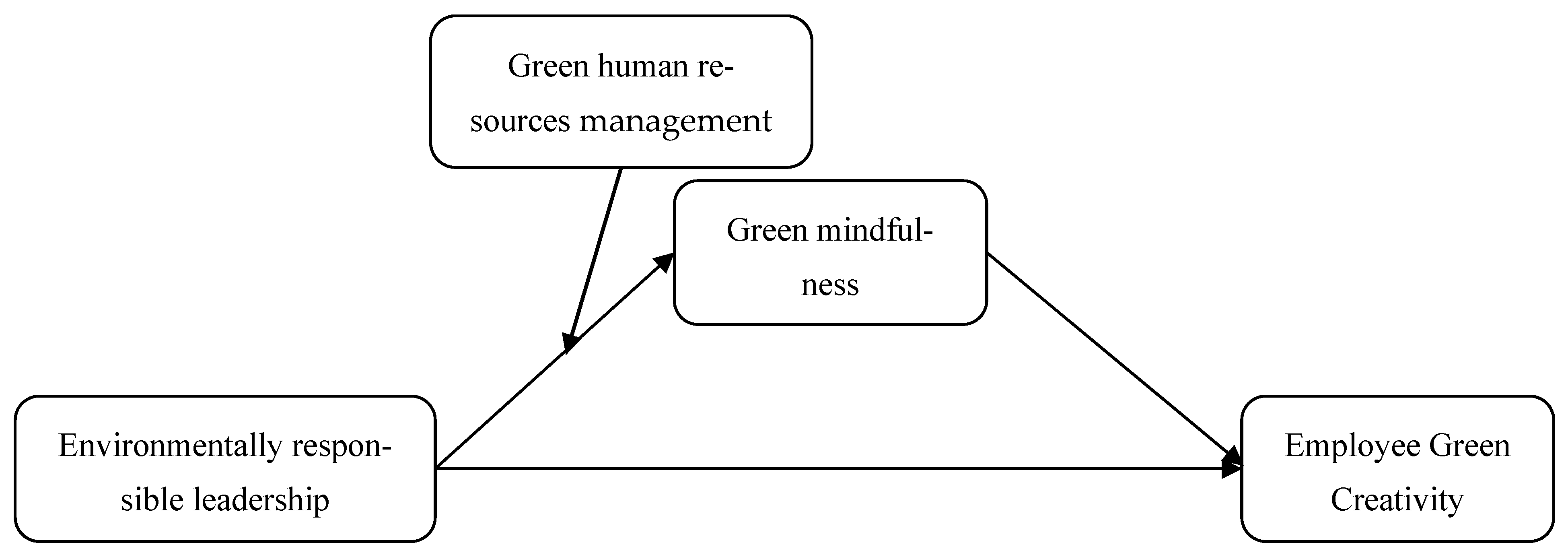

2. Theoretical Foundations and Hypothesis Development

2.1. ERL and EGC

2.2. The Mediating Role of GM

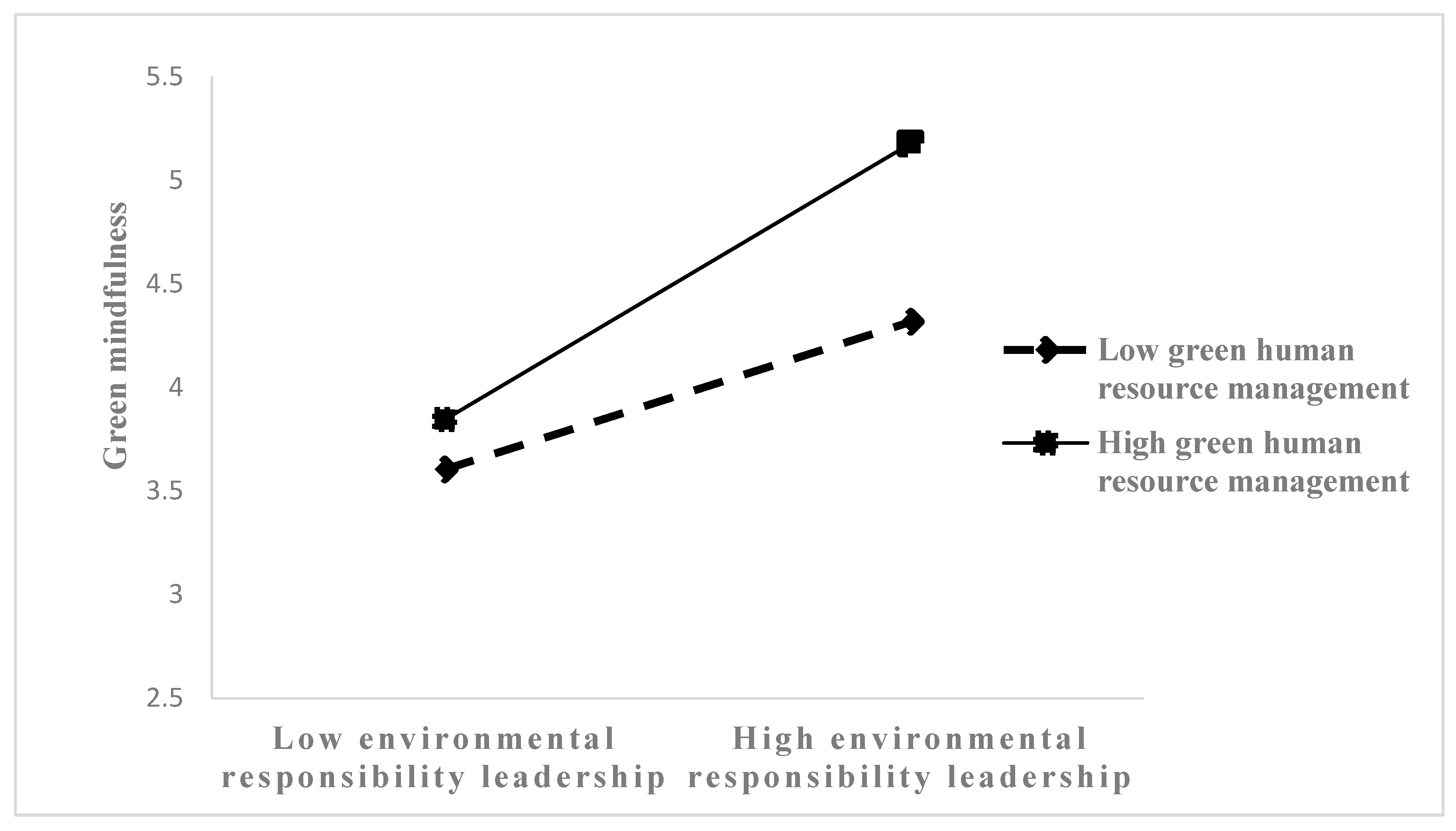

2.3. The Moderating Role of GHRM Practices

2.4. Moderated Mediation Effects

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

4. Results

4.1. Validation Factor Analysis

4.2. Common Method Bias Test

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

4.5. Summary of Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Overview of Key Findings

5.2. Theoretical Explanation for the Findings

5.3. Alignment with Previous Research

5.4. Implications of Key Patterns

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.1.1. Theoretical Implication

6.1.2. Managerial Implication

6.2. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, K.; Zhai, C.; Li, Y. Environmental protection tax and enterprises’ green technology innovation: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2024, 96, 103617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Su, W.; Hahn, J. How Green Transformational Leadership Affects Employee Individual Green Performance—A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Potočnik, K.; Zhou, J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Su, Q.; Hashmi, H.B.A.; Ho, T.H.; Julius, M.M. The role of green HRM in driving hotels′ green creativity. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1331–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Ali, F.; Shafique, I. Green mindfulness and green creativity nexus in hospitality industry: Examining the effects of green process engagement and CSR. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2653–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J. The greater the incentives, the better the effect? Interactive moderating effects on the relationship between green motivation and green creativity. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking Empowering Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creative Process Engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, M.T.; Wang, N.; Nazir, M.; Ferasso, M.; Saeed, A. Continuous Effects of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Employee Creativity: A Moderating and Mediating Prospective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 840019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Environmentally-specific servant leadership and green creativity among tourism employees: Dual mediation paths. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 28, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, K.; Kundi, Y.M.; Siddiquei, A.N.; Abualigah, A. Linking environmentally-specific empowering leadership to hotel employees′ green creativity: Understanding mechanisms and boundary conditions. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2023, 33, 412–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Tsai, K.-H. A sequential process from external stakeholder pressures to performance in services. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2022, 32, 589–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Fostering green service innovation perceptions through green entrepreneurial orientation: The roles of employee green creativity and customer involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2640–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M. Responsible Leadership in a Stakeholder Society—A Relational Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T. Responsible Leadership: Pathways to the Future. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Xiong, Z. How firms leverage corporate environmental strategy to nurture green behavior: Role of multi-level environmentally responsible leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, T.; Chen, Y.; Carmeli, A. CEO environmentally responsible leadership and firm environmental innovation: A socio-psychological perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Ni, M.; Huang, M.; Bao, Z. Environmentally-special responsible leadership and employee green creativity: The role of green job autonomy and green job resource adequacy. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 494, 144938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Kasser, T. Are Psychological and Ecological Well-being Compatible? The Role of Values, Mindfulness, and Lifestyle. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 74, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-H. Green Transformational Leadership and Green Performance: The Mediation Effects of Green Mindfulness and Green Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6604–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Zafar, A.; Shoukat, M.; Ikram, M. Green transformational leadership and green performance: The mediating role of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Int. J. Manag. Excell. 2017, 9, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Yeh, S.-L.; Cheng, H.-I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2014, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmesti, M.; Merrilees, B.; Winata, L. “I’m mindfully green”: Examining the determinants of guest pro-environmental behaviors (PEB) in hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 36, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Ramayah, T.; Fawehinmi, O. Nexus between green intellectual capital and green human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green human resource practices and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of collective green crafting and environmentally specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Patzer, M.; Scherer, A.G. Responsible Leadership in Global Business: A New Approach to Leadership and Its Multi-Level Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-H.; Wang, C.-K.; Lin, C.-Y. Antecedents and Consequences of Green Mindfulness: A Conceptual Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, T. Understanding Firm Performance on Green Sustainable Practices through Managers’ Ascribed Responsibility and Waste Management: Green Self-Efficacy as Moderator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, N.; Pickett, S.M. Mindfully green: Examining the effect of connectedness to nature on the relationship between mindfulness and engagement in pro-environmental behavior. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Toward a new measure of organizational environmental citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lülfs, R.; Hahn, R. Corporate greening beyond formal programs, initiatives, and systems: A conceptual model for voluntary pro-environmental behavior of employees. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee proenvironmental behaviors in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, H.; Tian, F.; Ho, J.A.; Zhang, G. Environmentally specific servant leadership and voluntary pro-environmental behavior in the context of green operations: A serial mediation path. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1059523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zibarras, L.D.; Coan, P. HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: A UK survey. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 2121–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee Green Behavior: A Theoretical Framework, Multilevel Review, and Future Research Agenda; The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, C.M.; O′Connor, E.J. Waking up! Mindfulness in the face of bandwagons. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Jabbour, C.J.; Muller-Camen, M.; Redman, T.; Wilkinson, A. Contemporary developments in Green (environmental) HRM scholarship. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Yusoff, Y.M. Green human resource management practices: A two-research investigation of ante-cedents and outcomes. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Green human resource management and green supply chain management: Linking two emerging agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How green human resource management practices can promote green employee behavior in China: A technology acceptance model perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 2, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Voegtlin, C. Development of a Scale Measuring Discursive Responsible Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.M.; Hatch, A.; Johnson, A. Cross-national gender variation in environmental behaviors. Soc. Sci. Q. 2004, 85, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K.; Freeman, E.C. Generational differences in young adults’ life goals, concern for others, and civic orientation, 1966–2009. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J. The role of employees′ leadership perceptions, values, and motivation in employees′ proven-vironmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L. The Nature, Measurement and Nomological Network of Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 151, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Naeem, R.M. Do green HRM practices influence employees′ environ-mental performance? Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Saeed, B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee′s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Carleton, E. Uncovering How and When Environmental Leadership Affects Employees’ Voluntary Pro-environmental Behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2017, 25, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, U.I.; Nisar, Q.A.; Nasir, N.; Naz, S.; Haider, S.; Khan, W. Green HRM, green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green corporate social responsibility. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 45353–45368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H.; Xu, H. Effects of green human resource management and managerial environmental concern on green innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlström, M.; Saru, E.; Vanhala, S. Sustainable Human Resource Management with Salience of Stakeholders: A Top Management Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Mohamad, Z.; Noor Faezah, J.; Muhammad, Z. Assessing the green behaviour of academics: The role of green human resource management practices and environmental knowledge. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Van Reenen, J. Why do management practices differ across firms and countries? J. Econ. Perspect. 2010, 24, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. gender | 1.649 | 0.478 | ||||||||

| 2. age | 2.061 | 0.692 | −0.062 | |||||||

| 3. edu | 3.099 | 0.508 | 0.018 | 0.081 | ||||||

| 4. time | 1.970 | 0.966 | −0.131 * | 0.810 ** | 0.061 | |||||

| 5. sec | 3.214 | 2.073 | 0.188 ** | −0.103 | −0.064 | −0.043 | ||||

| 6. ERL | 4.295 | 0.389 | −0.103 | 0.004 | 0.157 * | 0.032 | −0.146 * | |||

| 7. GM | 4.286 | 0.342 | −0.066 | 0.093 | 0.152 * | 0.052 | −0.138 * | 0.660 ** | ||

| 8. GHRM practices | 4.202 | 0.569 | −0.097 | 0.157 * | 0.136 * | 0.139 * | −0.245 ** | 0.659 ** | 0.692 ** | |

| 9. EGC | 4.231 | 0.469 | −0.135 * | 0.025 | 0.147 * | 0.004 | −0.119 | 0.554 ** | 0.652 ** | 0.577 ** |

| Variables | GM | EGC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Gender | −0.049 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.128 * | −0.086 | −0.087 |

| Age | 0.121 | 0.185 | 0.066 | 0.050 | 0.100 | 0.008 |

| Edu | 0.140 * | 0.040 | 0.017 | 0.144 * | 0.062 | 0.042 |

| Time | −0.066 | −0.121 | −0.091 | −0.065 | −0.110 | −0.049 |

| Sec | −0.110 | −0.027 | 0.044 | −0.084 | −0.015 | −0.002 |

| ERL | 0.653 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.206 * | ||

| GM | 0.505 ** | |||||

| GHRM practices | 0.516 ** | |||||

| ERL×GHRM practices | 0.206 * | |||||

| R2 | 0.047 | 0.451 | 0.577 | 0.049 | 0.321 | 0.447 |

| F | 2.552 * | 34.925 ** | 43.135 ** | 2.662 * | 20.135 ** | 31.100 ** |

| Grouping Statistics | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low GHRM practices (−1SD) | 0.243 | 0.078 | 0.097 | 0.405 |

| High GHRM practices (+1SD) | 0.340 | 0.119 | 0.156 | 0.618 |

| Intergroup differences | 0.097 | 0.041 | 0.059 | 0.213 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, B. Responsibility Driving Innovation: How Environmentally Responsible Leadership Shapes Employee Green Creativity. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104606

Han Z, Li Q, Li B. Responsibility Driving Innovation: How Environmentally Responsible Leadership Shapes Employee Green Creativity. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104606

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Zhiyong, Qi Li, and Bo Li. 2025. "Responsibility Driving Innovation: How Environmentally Responsible Leadership Shapes Employee Green Creativity" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104606

APA StyleHan, Z., Li, Q., & Li, B. (2025). Responsibility Driving Innovation: How Environmentally Responsible Leadership Shapes Employee Green Creativity. Sustainability, 17(10), 4606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104606