Exploring Equity in City Planning for Children’s Nature Play

Abstract

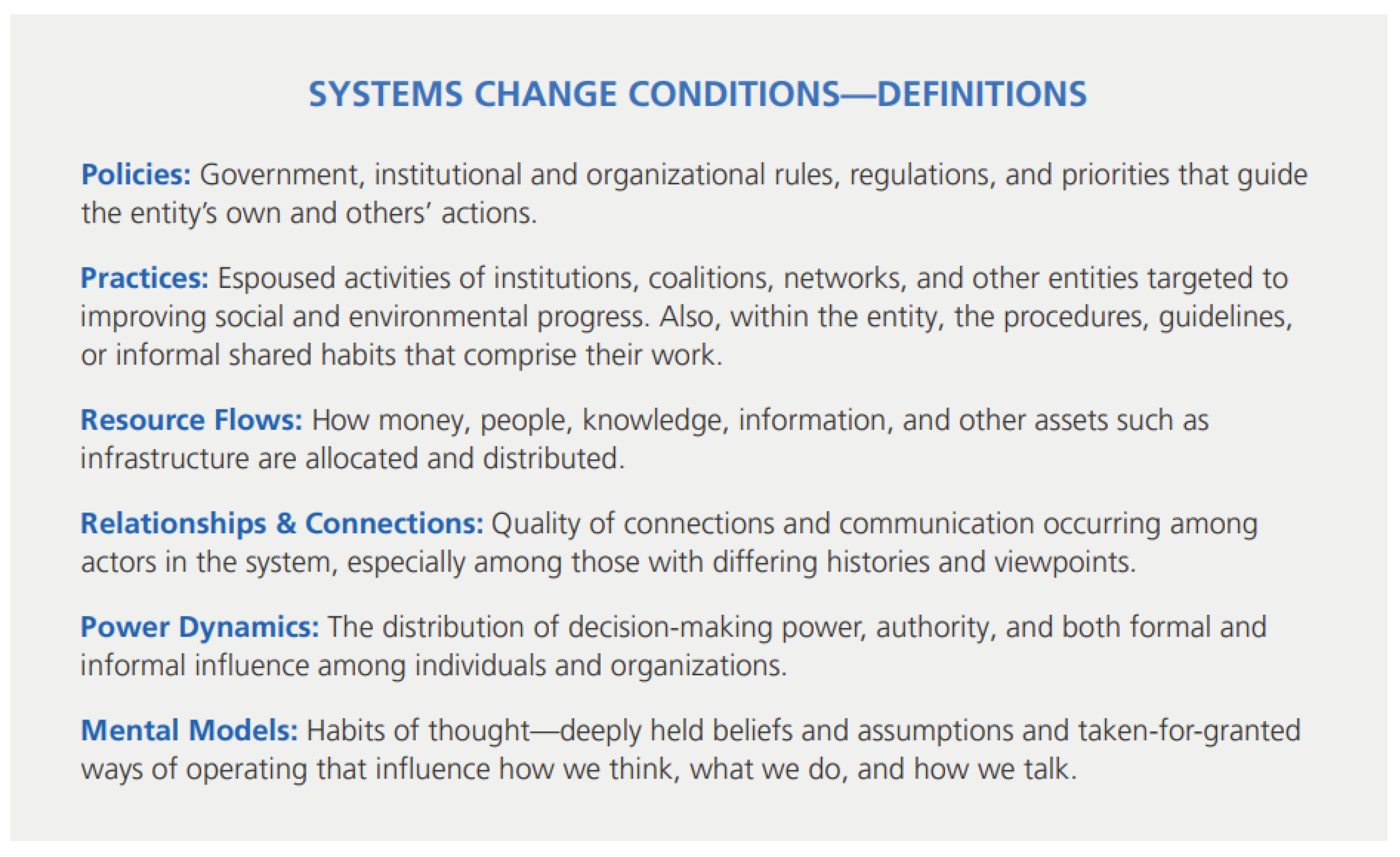

1. Introduction

2. Research Background

2.1. Exploring Concepts in Equitable Planning

2.2. Measuring Equitable Access to Nature Play Spaces

2.3. CCCN Systems Change Approach

“With a majority of children living in urban areas, city policies and programs play a critical role in connecting kids to green spaces and outdoor experiences. We help cities across the U.S. increase equitable access to nature”Children and Nature Network [53]

“Cities achieve equity when children and families stand on relatively equal footing, and race no longer predicts resources and opportunities for nature connection. Equity comes about through implementation of inclusive policies and practices and elimination of institutional racism” [54].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

- What are cities’ CCCN efforts to increase children’s nature play access in the U.S.?

- How is equity framed in these efforts?

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. What Are Cities’ CCCN Efforts to Increase Children’s Nature Play Access in the U.S.?

4.1.1. Policies

- Children’s Outdoor Bill of Rights

- Alignment with broader strategic planning goals and/or policies

- A list of outdoor experiences that every child has a right to experience.

- A public-facing symbol of the overarching goals a city or state has for its children’s outdoor experiences.

- A messaging tool that raises awareness of the importance of children’s connection to nature.

- A mayoral proclamation, city council resolution, value statement, or a framework for a program.

“…an initial policy, it’s kind of soft policy, it’s a resolution. So, it doesn’t necessarily have any teeth, but it’s helped align people into the vision”(Interviewee Response)

4.1.2. Practices

- Needs identification and equity mapping

- Community-led application processes to implement NPAs

- Collaborative and strategic planning processes

- Development of nature play design guidelines

- Installation of nature play features and/or “loose parts”

- Nature play signage

- Green schoolyards

- Education and programming

- Newsletters, workshops, and other community engagement methods

“Nature equity maps depict how natural green space appears in a city relative to key demographic, economic, and social vulnerability data. CCCN cities use these maps to prioritize park and natural spaces programming, renovation and acquisition projects, inform city plans, apply for funding, and develop public-facing messages to promote greater access to nature for young children”(Children and Nature Network, [64])

“…getting nature play to people who want it…” and “…answering, responding to the people who are interested in nature play and taking them through the steps”(Interviewee Response)

4.1.3. Resource Flows

“…a permanent full-time position…that’s when I began in 2018…that I think speaks volumes”(Interviewee Response)

“…one of the challenging pieces is that trying to find grant funding as a city agency can become a bit of a challenge. We often seek to do that through partnership because it’s a lot easier for our nonprofit partners to even go after funding. But also, to hold and manage that money”(Interviewee Response)

“… we collectively work with project partners and the school district, we’re raising USD 5 to 6 million a year to support 5 projects and that’s primarily grant funding”(Interviewee Response)

“…we work with the Low-Income Investment Fund…they’re like a banking organization that creates loans for programs but also provides grants. They’re working with the Department of Early Childhood; they’re the ones that are helping to fund and do the transformations at early childcare spaces for nature”(Interviewee Response)

4.1.4. Relationships and Connections

“…with forestry, with all of these different branches of city has been really helpful for us to come in again keep that community buy in and keep the momentum going”(Interviewee Response)

“…that’s why we go to the experts [the kids]. And so, we do. We do at least two of those sessions. We share all the quotations the kids take; we hand them our phone and the kids take a picture”(Interviewee Response)

4.1.5. Power Dynamics

“Definitely in every case we want community buy in and that’s like the commitment it takes to like getting the petition signed and like doing the surveys and kind of being an active part of the design sessions”(Interviewee Response)

“So as part of the process, we tried to be as intentional about outreaching to the community, about including youth voice in the design and the construction of the nature play space and at providing opportunities in multiple language so that many different people could participate”(Interviewee Response)

“…direction from above and below”(Interviewee Response)

“Anytime you go after grants, there is a chain of command that happens. So, there’s an official proposal request that we have to put forth and that goes up through Council, because you’re basically amending the city budget, so you have to receive Council approval in order to receive grant funding”(Interviewee Response)

“The mayor is the one that signs off on proclamations and things like that”(Interviewee Response)

“We have been incredibly lucky that the mayors that we have had over the past 10 years have been very big advocates for outdoor access”(Interviewee Response)

“We had a ton of support from the mayor. So he was very on board, very supportive, contributed funds to the infrastructure projects, was very vocal about the support of the programming and the initiative in general”(Interviewee Response)

“The head of the parks really is #1 supporter for this work, without that, I don’t think we could do what we could do, but also the cochairs, which are other heads of organizations”(Interviewee Response)

4.1.6. Mental Models

“…working on that kind of collective learning around racial equity we will bring in speakers that can talk about this, you know, much better than I ever could, and it runs the gamut. You know it’s anything. Language you know and words that we use and how do we reframe things to where we are not intentionally harming certain groups. It is looking at it from a different kind of strategy perspective”(Interviewee Response)

4.2. How Is Equity Framed in These Efforts?

“It’s not a one sentence. You know, it’s not one thing that solves this problem.”(Interviewee Response)

“I think it’s just access to green spaces is sort of how we define the equity. Do you have access to some space that you can find nature in? And that space may look very different for everyone. And we want to make sure that those spaces are created equitably throughout the city and not just in certain parts of the city.”(Interviewee Response)

“So, we approached equity more on who needs more nature rather than like who has it. But when you look at the map, you also realize that the ones that need it the most are also the ones that live in the areas with less opportunity to connect with nature.”(Interviewee Response)

“…The map doesn’t really tell us everything about the city or the community. So answering, responding to the people who are interested in nature play and taking them through the steps to kind of to get it to be a part of it together, to be a part of the process, and knowing that it’s an ongoing process that we’re evolving, that we’re learning as we go and how are different opportunities or access needs identified in regard to access to nature play”(Interviewee Response)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Question Prompt*

| *Adapted from CCCN Systems Change Outcomes Tool [54] |

| Interviewees: Program managers and/or staff working with implementing CCCN nature play initiatives |

| Interviewees are notified that they will be recorded. |

| 1. What strategies has the City of ______ used to increase access to children’s nature play? |

| 2. How do you define equitable nature play in ______? |

| 3. How are opportunities and access needs identified in regard to nature play access? |

| 4. How are children and youth who have historically been excluded identified? |

| 5. What aspects of equitable access to nature play has been the most difficult to address? |

| 6. What policies are you working on or have been implemented to support equitable access to nature play? |

| 7. What practices have been used? |

| 8. What relationships/connections have been formed? |

| 9. What resources do you have or plan to use? |

| 10. What kind of leadership engagement/support is there or has there been? |

| 11. Can you describe the decision-making processes for implementing nature play spaces in _______? |

| 12. Any additional things to discuss or questions? |

Appendix B. Summary of Interviewee Organizations and Job Titles

| Chicago, IL, USA | Nature Play Specialist | Department of Natural and Cultural Resources | Local Government |

| Outdoor and Environmental Education Manager | Chicago Park District | Local Government | |

| San Francisco, CA, USA | Director of the SF Children and Nature Collaborative | San Francisco Recreation and Park Department, City and County of San Francisco | Local Government |

| Manager of Strategic Planning | SF Recreation and Parks Department | Local Government | |

| Milwaukee, WI, USA | Green and Healthy Schools Program Manager | Reflo | 501(c)3 nonprofit based in Milwaukee, Wis. |

| Houston, TX, USA | Division Manager | Houston Parks and Recreation Department, Recreation and Wellness Division/Athletic and Aquatic Services | Local Government |

| Austin, TX, USA | Program Manager—Cities Connecting Children to Nature | City of Austin, Parks and Recreation Department | Local Government |

| Louisville-Jefferson County, KY, USA | Parks and Recreation Administrator | Natural Areas Division/Jefferson Memorial Forest, Louisville Metro Parks and Recreation | Local Government |

| Providence, RI, USA | Conservation Program Coordinator | Providence Parks Urban Wildlife Refuge Partnership | Collaboration among the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the RI National Wildlife Refuge Complex, the City of Providence Parks Department, and the Partnership for Providence |

| National League of Cities | Senior Program Specialist, Children and Nature | National League of Cities | An organization comprised of city, town, and village leaders that are focused on improving the quality of life for their current and future constituents |

References

- Chawla, L. Benefits of Nature Contact for Children. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, J.; Van Der Wilt, F.; Van Der Veen, C.; Hovinga, D. Nature Play in Early Childhood Education: A Systematic Review and Meta Ethnography of Qualitative Research. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 995164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, R. An Investigation of the Status of Outdoor Play. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2004, 5, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C.; Van Heezik, Y. Children, Nature and Cities: Rethinking the Connections; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin-de-Chavez, A.; Islam, S.; McEachan, R.R.C. Not a Level Playing Field: A Qualitative Study Exploring Structural, Community and Individual Determinants of Greenspace Use amongst Low-Income Multi-Ethnic Families. Health Place 2019, 56, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Schlosberg, D.; Craven, L.; Matthews, C. Trends and Directions in Environmental Justice: From Inequity to Everyday Life, Community, and Just Sustainabilities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Brand, A.L.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Corbera, E.; Kotsila, P.; Steil, J.; Garcia-Lamarca, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Cole, H.; Baró, F.; et al. Expanding the Boundaries of Justice in Urban Greening Scholarship: Toward an Emancipatory, Antisubordination, Intersectional, and Relational Approach. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 110, 1743–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.; Lewis, T. Green Gentrification: Urban Sustainability and the Struggle for Environmental Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, V.; Floyd, M.F.; Shanahan, D.; Coutts, C.; Sinykin, A. Emerging Issues in Urban Ecology: Implications for Research, Social Justice, Human Health, and Well-Being. Popul. Environ. 2017, 39, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, B. Equitable Urban Planning for Climate Change. J. Plan. Lit. 2023, 38, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, C. Child Friendly Cities and Land Use Planning: Implications for Children’s Health. Environments 2008, 35, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Candiracci, S.; Heinisch, L.M.; Moschonas, D.; Robinson, S.; Dixon, R.; Wu, Y.-P. (Eds.) Nature-Based Play: Fostering Connections for Children’s Wellbeing and Climate Resilience. 2022. Available online: https://www.arup.com/globalassets/downloads/insights/nature-based-play-fostering-childrens-wellbeing-and-climate-resilience.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Robert, K. Yin Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage Publication, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Manaugh, K.; Badami, M.G.; El-Geneidy, A.M. Integrating Social Equity into Urban Transportation Planning: A Critical Evaluation of Equity Objectives and Measures in Transportation Plans in North America. Transp. Policy 2015, 37, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.; Berney, R.; Kirk, B.; Yocom, K.P. Building Equity into Public Park and Recreation Service Investment: A Review of Public Agency Approaches. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 247, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advancing Equity Planning Now; Krumholz, N., Hexter, K.W., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5017-3038-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, V.; Johnson Gaither, C.; Gragg, R.S. Promoting Environmental Justice Through Urban Green Space Access: A Synopsis. Environ. Justice 2012, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J. (Eds.) The Green City and Social Injustice: 21 Tales from North America and Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, M.; Xu, D. A New Strategy for Planning Urban Park Green Spaces by Considering Their Spatial Accessibility and Distributional Equity. Forests 2024, 15, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, R.D. Environmental Justice: It’s More Than Waste Facility Siting. Soc. Sci. Q. 1996, 77, 493–499. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez del Pulgar, C.; Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J. Toward a Green and Playful City: Understanding the Social and Political Production of Children’s Relational Wellbeing in Barcelona. Cities 2020, 96, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, M.; Kronenberg, J. Classification of Institutional Barriers Affecting the Availability, Accessibility and Attractiveness of Urban Green Spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Langemeyer, J.; Borgström, S.; McPhearson, T.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J.; Barton, D.N.; Davis, M.; Naumann, S.; Röschel, L.; et al. Enabling Green and Blue Infrastructure to Improve Contributions to Human Well-Being and Equity in Urban Systems. BioScience 2019, 69, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R.A. Stepping Back from ‘The Ladder’: Refl Ections on a Model of Participatory Work with Children. In Participation and Learning; Reid, A., Jensen, B.B., Nikel, J., Simovska, V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 19–31. ISBN 978-1-4020-6415-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cele, S. Childhood in a Neoliberal Utopia: Planning Rhetoric and Parental Conceptions in Contemporary Stockholm. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2015, 97, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.L.; Brown, J.A.; Lee, K.J.; Pearsall, H. Park Equity: Why Subjective Measures Matter. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 76, 127733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, W. Soja Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, P.; Calder-Dawe, O.; Witten, K.; Asiasiga, L. A Prefigurative Politics of Play in Public Places: Children Claim Their Democratic Right to the City Through Play. Space Cult. 2019, 22, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Fernandez, M.; Harris, B.; Stewart, W. An Ecological Model of Environmental Justice for Recreation. Leis. Sci. 2019, 44, 655–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tink, L.N.; Kingsley, B.C.; Spencer-Cavaliere, N.; Halpenny, E.; Rintoul, M.A.; Pratley, A. ‘Pushing the Outdoor Play Agenda’: Exploring How Practitioners Conceptualise and Operationalise Nature Play in a Canadian Context. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2020, 12, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Lai, P.C.; Kwan, M.-P. Park and Neighbourhood Environmental Characteristics Associated with Park-Based Physical Activity among Children in a High-Density City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 68, 127479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanyile, S.; Fatti, C.C. Interrogating Park Access and Equity in Johannesburg, South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2022, 34, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, M.L.; Collins, T.W. Differential Access to Park Space Based on Country of Origin within Miami’s Hispanic/Latino Population: A Novel Analysis of Park Equity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, A.; Rutherford, G.W.; James, J.; Razani, N. Association of Neighborhood Parks with Child Health in the United States. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; He, J.; Liu, D.; Zhao, H.; Huang, J. Inequality in Urban Green Provision: A Comparative Study of Large Cities throughout the World. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, R.; Chen, B.; Wu, J. Inclusive Green Environment for All? An Investigation of Spatial Access Equity of Urban Green Space and Associated Socioeconomic Drivers in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 241, 104926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H. An Environmental Justice Study on Spatial Access to Parks for Youth by Using an Improved 2SFCA Method in Wuhan, China. Cities 2020, 96, 102405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Park, S. Investigating Spatial Heterogeneity of Park Inequity Using Three Access Measures: A Case Study in Hartford, Connecticut. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 151, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.; Jennings, V. Inequities in the Quality of Urban Park Systems: An Environmental Justice Investigation of Cities in the United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, E. Of Geography and Race: Some Reflections on the Relative Involvement of the Discipline of Geography in the Spatiality of People of Colour in the United States. Can. Rev. Am. Stud. 2016, 46, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, H.V.S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Anguelovski, I. Determining the Health Benefits of Green Space: Does Gentrification Matter? Health Place 2019, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulton, C.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Byrne, J. Factors Shaping Urban Greenspace Provision: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Towards a Better Understanding of the Relationship between Greenspace and Health: Development of a Theoretical Framework. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 118, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.T.; Ulrich, M.J.; Coleman, A. A call for applied sociology. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2010, 4, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.Y.; Ross, T.; Leo, J.; Buliung, R.N.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P. A Scoping Review of Evidence-Informed Recommendations for Designing Inclusive Playgrounds. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2021, 2, 664595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.M. Therapeutic Landscapes: From Exceptional Sites of Healing to Everyday Assemblages of Well-Being. In Routledge Handbook of Health Geography; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Emch, M.; Root, E.D.; Carrel, M. Health and Medical Geography, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hamraie, A. Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Children and Nature Network. Cities Connecting Children to Nature. Available online: https://www.childrenandnature.org/cities/cities-connecting-children-to-nature/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Children and Nature Network. Creating Systems Level Change in Cities: A Toolkit. Available online: https://www.childrenandnature.org/resources/creating-systems-level-change-in-cities-a-toolkit/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kania, J.; Kramer, M.; Senge, P. The Water of Systems Change; Policy Commons; FSG: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, A.; Wolfe, J.M. Discourse Analysis and City Plans. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1991, 10, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature Play Spaces: A Visual Tour. 2020. Available online: https://maps.communitycommons.org/entities/59ac5aa8-3bd2-40fd-9bbf-ba11b7f35805 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Cities Connecting Children to Nature—Nature Connection in Early Childhood Education. Available online: https://www.childrenandnature.org/wp-content/uploads/CCCN-Early-Childhood-Sites.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Department of Commerce. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles, Table DP05. 2023. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDP5Y2023.DP05?q=Chicago+city,+Illinois&g=160XX00US0667000,2148000,4459000,4805000,4835000,5553000&d=ACS+5-Year+Estimates+Data+Profiles (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Department of Commerce. Selected Economic Characteristics. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles, Table DP03. 2023. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDP5Y2023.DP03?q=Chicago+city,+Illinois&g=160XX00US0667000,2148000,4459000,4805000,4835000,5553000&d=ACS+5-Year+Estimates+Data+Profiles (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cities Connecting Children to Nature—Children’s Outdoor Bill of Rights (COBOR). Available online: https://www.childrenandnature.org/wp-content/uploads/CCCN_COBOR_whatis_21-1-20_final.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Children and Nature Network. Available online: https://www.childrenandnature.org/resources/equity-mapping-resource-guide-for-young-childrens-access-to-nature/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Cities Connecting Children to Nature Analysis. Available online: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/5f32d1fedcd84c03a1d558ea59861b92/ (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- San Francisco Recreation & Parks SF Children & Nature Partner Organizations. Available online: https://sfrecpark.org/1367/SF-Children-Nature-Member-Organizations (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Edward, W. Soja Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Whitzman, C.; Worthington, M.; Mizrachi, D. The Journey and the Destination Matter: Child-Friendly Cities and Children’s Right to the City. Built Environ. 2010, 36, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-315-07072-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, G.; Watson, S. City A/Gender. In The Blackwell City Reader; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tang Yan, C.; Moore De Peralta, A.; Bowers, E.; Sprague Martinez, L. Realmente Tenemos La Capacidad: Engaging Youth to Explore Health in the Dominican Republic Through Photovoice. J. Community Engagem. Scholarsh. 2019, 12, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.; Lee, K.; Shin, S. Access to Urban Green Space in Cities of the Global South: A Systematic Literature Review. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Population | % Persons Under 18 | Median HH Income |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago, IL, USA | 2,707,648 | 19.8% | USD 75,134 |

| Houston, TX, USA | 2,300,419 | 23.6% | USD 62,894 |

| Austin, TX, USA | 967,862 | 18.3% | USD 91,461 |

| San Francisco, CA, USA | 836,321 | 13.7% | USD 141,446 |

| Louisville-Jefferson County, KY, USA | 627,210 | 22.5% | USD 64,731 |

| Milwaukee, WI, USA | 569,756 | 25.6% | USD 51,888 |

| Providence, RI, USA | 190,214 | 20.2% | USD 66,772 |

| Structural | Relational | Transformative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policies | Practices | Resource Flows | Relationships and Connections | Power Dynamics | Mental Models |

| 1. Children’s Outdoor Bill of Rights 2. Alignment with broader strategic planning goals and/or policies | 1. Needs identification and equity mapping 2. Community-led application processes to implement nature play spaces 3. Collaborative and strategic planning processes 4. Development of nature play design guidelines 5. Design charrettes, workshops with community input 6. Installation of nature play features and/or “loose parts” 7. Nature play signage 8. Green schoolyards 9. Education and programming 10. Newsletters, workshops, surveys, and other community education/engagement methods | 1. Dedicated staff positions 2. Dedicated city funds 3. Non-profit partners 4. Public–private partnerships 5. Intergovernmental agreements 6. Contracting 7. Grants 8. Volunteers 9. Donors, fundraisers | 1. Citywide collaboratives 2. Community engagement, programming, education 3. Intergovernmental agreements 4. Non-profit partners 5. Public–private partnerships | 1. Stated city leadership support 2. Inter-departmental city support and coordination 3. Formal city approval processes 4. Community-led application processes 5. Neighborhood councils, associations, community group input 6. Partnerships, funding | 1. Workshops and training 2. Engagement with community or community-led processes 3. Volunteer opportunities |

| Equity as a Lens | Equity as an Outcome | Equity as a Process |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Equity/inequity as a problem to identify and solve 2. The problem is a complex set of issues 3. The problem can be seen or identified through spatial analysis 4. The problem includes historic and persisting exclusions, identified by differences in spatial access across income, race/ethnicity 5. There are metrics to identify problem but depends how data are examined, what is included in analysis 6. There is not one solution | 1. General increases in access, safety, and health for “all” 2. Achieving specific outcomes of increasing availability, safety, and quality of nature to areas identified as lacking access 3. Achieving outcomes that increase nature access for people who may need it most based on identified disadvantages 4. Identified target populations, such as low-income individuals or people of color, based on historic and current data 5. Providing access to those who want nature play | 1. Equity as something to work towards 2. A journey 3. Process of learning/unlearning 4. Incorporation of inclusive design processes 5. Engagement with families, communities 6. Collective processes with partners 7. Input in decision making 8. Processes for those who express wants |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

VanSickle, M.; McSorley, M.; Coutts, C. Exploring Equity in City Planning for Children’s Nature Play. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4538. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104538

VanSickle M, McSorley M, Coutts C. Exploring Equity in City Planning for Children’s Nature Play. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4538. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104538

Chicago/Turabian StyleVanSickle, Melissa, Meaghan McSorley, and Christopher Coutts. 2025. "Exploring Equity in City Planning for Children’s Nature Play" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4538. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104538

APA StyleVanSickle, M., McSorley, M., & Coutts, C. (2025). Exploring Equity in City Planning for Children’s Nature Play. Sustainability, 17(10), 4538. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104538