Abstract

In the context of an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) business environment, the ability of an enterprise to develop a robust and resilient business model is critical for its long-term sustainability. Although existing research has delved into the relationship between enterprise behavior and business model resilience, most of these studies, which predominantly adopt an enterprise-centric perspective, rely on qualitative methodologies. Consequently, there is a notable gap in quantitative research examining the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience. To bridge this research gap, this study, grounded in dynamic capability theory, conducts an empirical investigation using a sample of 300 questionnaires to explore the intricate internal mechanisms underlying the impact of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience. The findings reveal that enterprises engaging in more frequent interactions with users tend to exhibit stronger business model resilience. Furthermore, dynamic capability serves as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience. Additionally, knowledge-oriented leadership, as an emerging leadership style, plays a moderating role in the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and dynamic capability, as well as in the mediating effect of dynamic capability. This study contributes to the literature by deepening the understanding of the interplay between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience. Moreover, it offers practical insights for enterprises seeking to enhance their business model resilience in the VUCA era.

1. Introduction

In a business environment where the characteristics of the VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) era are increasingly prominent and sudden crisis events keep emerging [1], why can some business models continuously create value for enterprises and their stakeholders, while others fail to support enterprises in successfully weathering business crises? Based on previous research, whether an enterprise’s business model is resilient can effectively answer this question [2]. Resilience is understood as the ability of a system to continue to function and achieve its goals when facing challenges [3]. It reflects the system’s capacity to rapidly recover from adversity and utilize relevant resources for effective decision making [4]. On this basis, business model resilience can be defined as the ability of an enterprise’s business model to resist the interference of the external volatile environment, enabling the enterprise to quickly recover from a crisis and even exceed its original production capacity, continuously creating value [5]. Generally speaking, a highly resilient business model exhibits a high degree of flexibility and adaptability [6]. It can often assist an enterprise in rapidly recovering from a crisis and even achieving a comeback in an adverse situation [5]. Conversely, if a business model lacks resilience, when facing sudden crisis events, it is often difficult for the enterprise to turn the situation around, and its business model may be damaged or even destroyed. Therefore, in today’s increasingly volatile business environment with frequent adverse events, enhancing business model resilience to continuously create value urgently requires the high attention of researchers.

As a specific manifestation of resilience in the context of business models, business model resilience, to a certain extent, reflects the sustainable and hard-to-replicate competitive advantages of an enterprise. According to the dynamic capability theory, dynamic capability refers to an enterprise’s ability to efficiently integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external knowledge, resources, and skills [7]. As a dynamic and high-order ability, it has the function of optimizing the organizational mode on which the organization depends for survival. When the existing organizational mode fails to adapt to the changes in internal and external environmental goals and becomes inefficient or even ineffective [8], dynamic capability can play a crucial role in enabling the enterprise to maintain long-term performance [9], establish long-term competitive advantages, and adapt to a rapidly changing environment [7,10]. Based on this, enterprise dynamic capability may be an important antecedent for enhancing business model resilience. Furthermore, in contrast to the traditional resource-based view which mainly adopts a static perspective, the dynamic capability theory places enterprises in a dynamic development process. It holds that relying solely on the enterprise’s original resource advantages is difficult for the enterprise to establish and maintain sustainable competitive advantages. Coupled with an increasingly volatile and fierce competition in the business environment, enterprises urgently need to re-integrate their internal and external resources according to external environmental changes [11]. This means that enterprises should actively perceive changes in the external environment and can reconstruct their resource base through cooperation with other stakeholders in the business system [12], ultimately forming an ability that can bring sustainable competitive advantages to the enterprise [13]. This requires us to further explore the sources of dynamic capability that contribute to enhancing business model resilience.

Dynamic capability theory posits that an enterprise’s dynamic capability does not merely reside within the enterprise nor remain static. Instead, they gradually take shape and develop during the interaction process between the enterprise and its external environment [14]. In the current era of user economy, the development of emerging technologies such as big data and AI is gradually altering the power and status of users in the course of enterprise development [15]. As one of the enterprise’s stakeholders, users are no longer just the purchasers and beneficiaries of enterprise products and services, they have become a crucial source for enterprises to acquire heterogeneous market knowledge and significant value-based resources [16]. Based on this, an increasing number of enterprises have started to engage in interaction behaviors with users, and the aim is to excavate valuable resources from the in-depth perspective of users, thereby achieving the integration, reconstruction, and re-configuration of the enterprise’s internal and external resources. By continuously enhancing the enterprise’s dynamic capability [7], the continuous and efficient operation of the enterprise’s business model can ultimately be ensured. However, a review of existing research reveals that both domestic and foreign scholars’ research on business model resilience mostly focuses on the enterprise-centered perspective. They mainly explore the impacts of individual (such as enterprise employees, entrepreneurs) characteristics and their behaviors on business model resilience from perspectives such as knowledge empowerment and network theory [17]. Moreover, these studies are mostly qualitative, and there is a lack of quantitative research methods based on the dynamic capability theory to explore how enterprise–user interaction can enhance enterprise dynamic capability and ultimately enhance business model resilience. To some extent, this may lead to the ambiguity in the formation mechanism of business model resilience. On the other hand, regarding the research on enterprise–user interaction, previous scholars mainly focused on its impacts on aspects such as product innovation performance [18], product innovation paths, and user innovation performance [19]. They seldom explored, from the theoretical perspective of dynamic capability, whether enterprise–user interaction can accelerate the enterprise’s integration and reconstruction of its resource base. Although some scholars have pointed out that this interaction behavior is conducive to the innovation of the business model [20], they have not investigated the impact mechanism of this interaction behavior on business model resilience. To a certain extent, this weakens the theoretical explanation of enterprise–user interaction.

In fact, in today’s increasingly volatile business environment, enterprise–user interaction offers a new research perspective for enhancing business model resilience. In a rapidly changing market environment, valuable, scarce, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources constitute an important foundation for the formation of an enterprise’s dynamic capability [11,14]. Enterprise–user interaction, as an interaction behavior between an enterprise and its stakeholders, provides a favorable channel for the enterprise to acquire valuable and scarce resources. During the process of interacting with users, the enterprise can deeply excavate rich user-demand information and heterogeneous resources from the user’s perspective [18]. Moreover, in the continuous process of interaction, the enterprise can innovatively update and allocate its internal and external resources. It can continuously renew the value-creation logic of its business model, enhancing the adaptability and sustainability of the business model in the commercial environment. Furthermore, the formation of enterprise dynamic capability requires two major processes: resource identification and allocation [11]. However, in the actual business environment, due to the dual influence of environmental complexity and the enterprise’s actual goals, a large number of resources obtained through enterprise–user interaction may be difficult to efficiently allocate into valuable resources required for enhancing dynamic capability. In other words, only through efficient integration and allocation can the resources acquired from enterprise–user interaction contribute to improving enterprise dynamic capability and further strengthening business model resilience [9]. From the perspective of the planning view, enterprise dynamic capability is continuously accumulated under the strategic plans formulated by leaders [21]. The individual characteristics of leaders will, to a certain extent, affect the transformation process of enterprise resources, thus determining the evolution of the dynamic capability. Based on this, from the perspective of the leadership style, we introduce the moderating variable of knowledge-oriented leadership to explain the mechanism of enterprise integration and allocation of heterogeneous knowledge resources. Knowledge-oriented leaders attach importance to the role of knowledge in enterprise development and encourage employees to actively engage in knowledge learning and resource innovation [22,23]. Under this influence, the user resources obtained after enterprise–user interaction will be more efficiently allocated into valuable and unique resources. This promotes the renewal and reconstruction of the enterprise’s resource base, strengthens the positive impact of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability, and further enhances the indirect effect of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience through enterprise dynamic capability.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, this study explores the impact mechanism of enterprise–user interaction on enhancing business model resilience from the perspective of dynamic capability theory, and deeply analyzes the mediating role of enterprise dynamic capability and the moderating role of knowledge-oriented leadership. This study has certain research contributions in terms of theoretical extension, empirical innovation, and practical relevance. Firstly, in terms of theoretical extension, this study is distinct from traditional research on dynamic capability. Starting from the perspective of enterprise–user interaction, it explores how the user information and resources obtained after enterprise–user interaction are transformed into the enterprise’s resource base, thereby enhancing business model resilience, as well as the moderating role of knowledge-oriented leadership in this process. This new theoretical framework not only deepens the understanding of the dynamic capability theory in the context of enterprise–user interaction, expands the scope and applicable scenarios of the dynamic capability theory, but also provides a more comprehensive theoretical explanation for the formation mechanism of business model resilience in the era of knowledge economy. Secondly, in terms of empirical innovation, this study uses methods such as structural equation modeling and hierarchical regression to confirm the positive impact of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience, the mediating role of enterprise dynamic capability, and the positive moderating role of knowledge-oriented leadership. Finally, in terms of practical relevance, this study provides guidance for enterprise practices in the era of knowledge economy. Enterprises should regard enterprise–user interaction as a key strategy, formulate personalized enterprise–user interaction strategies based on their actual situations, use diversified interaction channels and methods to obtain heterogeneous user information and resources, and reshape enterprise dynamic capability on this basis to enhance business model resilience. At the same time, as the helmsmen of the enterprise development path, leaders should clearly recognize the crucial role of heterogeneous knowledge resources in the sustainable development of enterprises, and continuously strengthen the positive effects of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability and business model resilience.

2. Theoretical Basis and Hypotheses

2.1. The Application of Dynamic Capability Theory in the Research of Business Model Resilience

A business model reflects the logic or framework by which an enterprise creates, delivers, and captures value [24]. Its elements include value network, value creation, value capture, and strategic choices, among others. Value creation is the core element of a business model [25]. This research highlights the crucial role of users in delivering the enterprise’s value proposition and constructing its business model. With the deepening complexity of the business environment and the application of emerging technologies, unpredictable crisis events have occurred more frequently. These events have brought huge challenges and impacts to the business model of enterprises. In this context, the academic community has introduced the research on resilience into the field of business models and proposed the concept of business model resilience to measure the adaptability and recovery ability of an enterprise’s business model in adverse situations [5]. Based on previous studies, heterogeneous information and resources obtained by enterprises from the external environment form an important foundation for enhancing business model resilience [17]. However, most existing studies take external heterogeneous information and resources as preconditions to explore their impact on the process of business model resilience, while rarely addressing how enterprises acquire such heterogeneous information and resources and transform them into business model advantages.

With the rapid changes in the market environment, the resource-based view, which mainly adopts a static perspective, has gradually become difficult to explain how enterprises can continuously obtain competitive advantages in a dynamic environment. Based on this, Teece proposed the dynamic capability theory by placing enterprises in a dynamic development environment. They argued that dynamic capability refers to an enterprise’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources to respond to rapid environmental changes [7]. This perspective emphasizes that enterprises should update their resource base and dynamic capability in an ever-changing market environment to meet new market requirements and establish and maintain sustainable competitive advantages [14]. Consequently, this study is based on the dynamic capability theory to explore how the heterogeneous information and resources obtained after enterprise–user interaction are transformed into the enterprise’s value advantages and ultimately enhance the business model resilience. The justifications are as follows: First, the impact mechanism of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience involves the enterprise’s integration and allocation of heterogeneous information and resources, which aligns with the analytical framework of the dynamic capability theory [7]. Second, business model resilience reflects the recovery and sustainability of an enterprise’s business model in a volatile environment. A highly resilient business model often implies that the enterprise has sustainable competitive advantages. Therefore, to some extent, business model resilience can be understood as the manifestation of the sustainable competitive advantages brought about by the enterprise’s dynamic capability in the business model. Third, existing research on resilience mostly adopts an individual-psychological perspective and attributes resilience to three aspects: adaptability, stress resistance, and post-traumatic growth. However, in the research on business model resilience at the organizational level, there is relatively little exploration of the capability that serves as the source of such resilience. Thus, this paper applies the dynamic capability theory to the research on business model resilience, which, to a certain extent, expands the application scenarios and scope of the dynamic capability theory and also provides a new theoretical perspective for the research on business model resilience.

2.2. Enterprise–User Interaction and Business Model Resilience

As one of the core variables in positive psychology, resilience is regarded as positive psychological capital [26]. It reflects an individual’s resilience, stress resistance, and post-traumatic growth ability, enabling individuals to quickly recover from adversity [3]. As a specific manifestation of resilience in the context of business models, business model resilience can, to some extent, be understood as the business model of an enterprise possessing unique, sustainable competitive advantages and long-term sustainability [27]. In this study, we define business model resilience as the ability of an enterprise’s business model to resist the interference and impact of the external environment, helping the enterprise maintain long-term competitive advantages and continuously create value [5]. Previous research has indicated that the enhancement of business model resilience is inseparable from heterogeneous information and resources in the external environment [17]. Enterprise–user interaction, as one of the channels for enterprises to obtain user information and resources, plays a non-negligible role in the process of enterprises forming highly resilient business models.

Dynamic capability theory focuses on how enterprises maintain their competitive advantages in a rapidly changing environment by integrating, constructing, and reconfiguring their resources and capabilities [7]. Based on this, valuable and scarce resources in the external environment serve as an important foundation for enterprises to achieve sustainable competitive advantages [11]. Enterprises need to efficiently integrate these resources and continuously update their existing resource and capability bases to sustain their long-term survival in a volatile environment. According to this framework, business model resilience, as the manifestation of an enterprise’s sustainable competitive advantages in its business model, largely depends on the transformation of the competitive advantages of the heterogeneous resources obtained during the enterprise–user interaction process. During the enterprise–user interaction, users, as carriers, offer more possibilities for enterprises to acquire rich market information and user resources. Enterprises can start from the in-depth perspective of users, understand users’ true inner thoughts and tap into their latent needs through various means such as online and offline channels [18], and extract valuable resources that can be integrated and allocated by the enterprise from users’ feedback and expressions. Subsequently, based on a further analysis of these valuable resources, enterprises can more accurately predict the development trends of the user market and unexpected events that may impact the business model. Thereby, they can continuously update the underlying value logic of the business model and construct a business model that aligns with user needs according to the enterprise’s existing resource base [28], so as to adjust business strategies in a timely manner. Eventually, the resilience and sustainability of the business model can be continuously enhanced [17]. In summary, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1:

Enterprise–user interaction has a positive impact on business model resilience.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Enterprise Dynamic Capability

2.3.1. Enterprise–User Interaction and Enterprise Dynamic Capability

In the context of the burgeoning user economy, the role of users has transcended the traditional confines of being mere consumers [19]. The advent of personalized and dynamic consumption demands has spurred users to actively engage in the product design process. In this regard, enterprise–user interaction serves as an efficacious conduit for users to articulate their personalized requirements. By means of interacting with users, enterprises are enabled to comprehensively acquire crucial information and resources within the user market, as well as gain access to users’ authentic evaluations of the enterprise’s products and services. Consequently, enterprises can innovate their products and services in a more targeted fashion, enhance the congruence between enterprise offerings and user demands [29], and unearth new competitive opportunities. This, in turn, contributes to the augmentation of the enterprise’s dynamic capability within the business environment.

According to the dynamic capability theory, the formation of enterprise dynamic capability does not occur solely within the enterprise [30]. Relying merely on the enterprise’s original internal resources makes it difficult for the enterprise to maintain its long-term competitiveness in a dynamic environment. Hence, during the process of integrating and reconfiguring internal and external resources, enterprises need to develop a high-order capability that enables them to cope with environmental changes [7]. Enterprise–user interaction, as a novel form of interaction, offers a new approach for enhancing such high-order enterprise dynamic capability. During the interaction with users, enterprises can gather diverse users’ usage experiences and feedback regarding the enterprise’s products or services through direct means (such as interviews and product launches) or indirect methods (questionnaires, online platforms, etc.) [18]. Based on the interaction outcomes, enterprises can delve into users’ profound inner needs, while users can actively voice their personalized requirements, genuine evaluations of existing products, and future expectations. Consequently, this interaction behavior furnishes an opportunity for resource exchange between enterprises and users, and also expedites the efficiency of enterprises in integrating resources in the user market. Subsequently, drawing on these valuable resources obtained, enterprises can perceive the overall market from the users’ perspective and continuously roll out new products and services accordingly [18]. Meanwhile, in the course of meeting users’ personalized demands, enterprises can accomplish a profound renewal and reconfiguration of their resource base, continuously upgrade their capacity to respond to complex and ever-changing environments [31], and further enhance their dynamic capability. In summary, the following hypothesis is put forward:

H2a:

Enterprise–user interaction has a positive impact on enterprise dynamic capability.

2.3.2. Enterprise Dynamic Capability and Business Model Resilience

The dynamic capability theory posits that dynamic capability, as a type of high-order capability, exerts a significant influence on the formation and maintenance of an enterprise’s long-term competitive advantages [32]. Robust dynamic capability can assist an enterprise in achieving long-term adaptability in a competitive environment and promoting its sustainable growth in a volatile context [14,33]. In a rapidly changing business environment, the business model, being a crucial factor influencing an enterprise’s survival, development, and competitive success, the strength of its resilience reflects, to some extent, whether the enterprise possesses sustainable competitive advantages. Based on this, strong enterprise dynamic capability is highly likely to enhance the resilience of the enterprise’s business model and facilitate its sustainable growth. On the one hand, the dynamic capability is an important source of an enterprise’s sustained competitive advantages and a key competence essential for the enterprise to achieve business model innovation and enhance business model resilience [32,34]. When the market environment undergoes turbulent changes, a powerful dynamic capability can support the enterprise to respond flexibly, thereby reducing the impact of unexpected events on the business model and improving the adaptability and sustainability of the business model [35]. On the other hand, from the perspective of the business model, enterprise dynamic capability plays a role in promoting the optimization and renewal of the business model [36]. When problems arise in the enterprise’s development, dynamic capability can help the enterprise optimize and update the underlying logic of the business model in a timely manner based on the internal and external environment [8]. This includes resource allocation methods, new product development, the optimization of the operation mode, and technological iteration and upgrading, etc., thus ensuring that the business model can continuously create value for the enterprise and its stakeholders [37]. In summary, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2b:

Enterprise dynamic capability has a positive impact on business model resilience.

Integrating H1, H2a, and H2b, we postulate that the impact of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience might be mediated by enterprise dynamic capability. Specifically, in line with the dynamic capability theory, enterprises are required to develop a high-order capability, namely dynamic capability, which can endow the enterprise with sustainable competitive advantages during the process of integrating, constructing, and reconfiguring internal and external resources. In this process, enterprise–user interaction, as a novel interaction behavior, offers more possibilities for enterprises to acquire market resources. The heterogeneous resources obtained during the enterprise–user interaction can assist enterprises in continuously integrating and reconstructing their resource base in accordance with external environmental changes and realizing the enhancement of enterprise dynamic capability in the continuous interaction process. Powerful dynamic capability provides a prerequisite for enhancing the resilience of an enterprise’s business model. Dynamic capability enables enterprises to accurately grasp the development trends of the user market and formulate new value-creation logics based on changes in the market environment. Meanwhile, dynamic capability also contributes to improving the enterprise’s perception of unexpected events and potential crises. When a crisis looms, the enterprise can make advance arrangements and adjust its business strategies in a timely manner, thereby reducing the impact of unexpected events on the business model and further enhancing business model resilience. Based on this, the following hypothesis is further proposed:

H2:

Enterprise dynamic capability plays a mediating role in the process of the impact of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Knowledge-Oriented Leadership

As a novel leadership style, knowledge-oriented leadership exerts two major functions: communication and motivation [22]. Communication here implies that leaders are adept at listening to employees’ opinions, bestowing them with ample trust and respect. Meanwhile, they tolerate employees’ mistakes and encourage continuous innovation among them [23]. Motivation means that leaders attach great importance to both internal and external knowledge and endeavor to lead by example. They strive to foster a favorable learning and innovation atmosphere within the organization to rectify employees’ learning attitudes and enhance their knowledge utilization efficiency. Additionally, knowledge-oriented leaders reward employees for their learning and innovation behaviors [38], thereby stimulating employees’ enthusiasm for learning, utilizing heterogeneous knowledge, and sustaining innovation. Consequently, to a certain extent, knowledge-oriented leadership accelerates the process of resource integration and allocation following enterprise–user interaction, and thus strengthens the positive impact of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability.

The dynamic capability theory posits that the resources obtained from the external environment do not always contribute to the enhancement of enterprise dynamic capability. Only when internal and external resources are fully integrated and efficiently allocated can the enterprise’s resource base be continuously updated and reconfigured [11], thereby improving the enterprise’s dynamic capability. During the dynamic interaction between enterprises and users, from the in-depth perspective of users, it can bring different user demand information and heterogeneous market resources to the enterprise. These unique resources form an important foundation for the enterprise to enhance its dynamic capability [7]. Under the influence of knowledge-oriented leadership, the unique resources obtained after enterprise–user interaction can be rapidly transformed into the enterprise’s dynamic capability advantage, facilitating the improvement of the enterprise’s dynamic capability [9]. Specifically, knowledge-oriented leadership encourages enterprise employees to actively engage in knowledge learning and innovation [22,38]. Driven by the leadership’s example, employees will actively integrate new knowledge and develop new thinking [39]. As a result, the enterprise can fully absorb the valuable user information resources obtained after enterprise–user interaction and creatively integrate them with the enterprise’s original resources. This accelerates the process of the enterprise constructing and reconfiguring its resource base, and improves the enterprise’s ability to allocate and restructure internal and external resources. However, without the promoting effect of knowledge-oriented leadership, even if enterprise–user interaction brings a large number of heterogeneous resources to the enterprise, these resources are difficult to efficiently integrated and cannot contribute to the reconstruction of the enterprise’s resource base. At this time, the promoting effect of enterprise–user interaction on the enterprise’s dynamic capability will be weakened. In summary, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3:

Knowledge-oriented leadership positively moderates the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability.

Integrating H2 and H3, this paper constructs a moderated-mediation model to explore the impact process of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience and the moderating role of knowledge-oriented leadership. Specifically, the stronger the knowledge-oriented leadership, the stronger the learning and innovation atmosphere within the enterprise. Employees possess strong knowledge-learning and innovation capability, enabling them to continuously generate new ideas and develop new approaches. In this case, the enterprise can innovatively integrate the vast resources obtained from user interaction and reconfigure its resource base in accordance with external environmental changes. During this process, the enterprise can achieve the continuous upgrading of its dynamic capability, thereby strengthening the positive impact of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability. Once the enterprise’s dynamic capability is enhanced, the enterprise can better respond to external environmental emergencies, which will improve the adaptability and sustainability of the business model and ultimately enhance business model resilience. Conversely, if the knowledge-oriented leadership in the enterprise is weaker, the knowledge resources obtained after enterprise–user interaction are difficult to efficiently transform into resource advantages. As a result, the positive impact of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability and its indirect effect on business model resilience will be weakened. In summary, the following hypothesis is further proposed:

H4:

The mediating role of enterprise dynamic capability between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience is moderated by knowledge-oriented leadership.

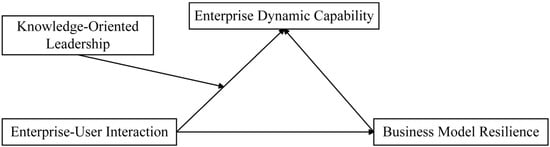

Based on the above analysis, the theoretical model of this paper is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Research Design

3.1. Samples

Before the formal survey, we distributed 67 initial paper questionnaires that had gone through the processes of translation and back-translation to MBA students, and tested the reliability and validity of each variable. After inspection, the Cronbach’s α coefficient and the KMO value of each variable were both greater than 0.7, which met the general standards. Subsequently, we officially launched the questionnaire survey, which was conducted from June to August 2024. First, for online data collection, we utilized a professional questionnaire-collecting company to gather data samples. The target sample population was set as enterprise employees. Moreover, in the questionnaire instructions, the purpose of this survey and the requirements for filling out the questionnaire were elaborated in detail to enhance the quality of questionnaire collection. In this way, a total of 354 questionnaires were distributed, and 325 were collected. Second, for offline data collection, paper-based questionnaires were distributed to researchers and their relatives and friends working in enterprises, and their questions were patiently answered. Through this method, a total of 50 questionnaires were distributed, and 47 were collected. In total, 404 questionnaires were distributed in the two-phase survey, and 372 were collected. Subsequently, questionnaires that did not meet the research conditions and those with obvious filling problems (such as choosing only one option throughout or having obvious logical errors) were excluded. As a result, a total of 300 questionnaires were valid, for an effective response rate of 74.26%. The distribution of statistical characteristics of the research sample is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistical distribution of sample characteristics (N = 300).

Due to the use of three methods to collect data for this article, it was necessary to examine the possibility of sample differences across these questionnaire collection methods. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to test data from different sample sources, and the results revealed that the samples basically belonged to the same matrix; thus, the differences caused by the use of three different data collection methods were not significant. Next, Harman’s single-factor analysis was used to test the possibility of common method variance. The main factor identified resulted in a 35.55% difference, less than 40% of the general standard, thus indicating that the common method variation was within an acceptable range.

3.2. Measurement

Mature, previously developed scales were used to measure variables in this study. Firstly, regarding the translation process. Since the initial measurement scales for BMR and KOL were in English, we invited two teachers majoring in English to independently translate the original English scales into Chinese. Then, we compared the translations of the two teachers and integrated the differences to form the initial Chinese scale. Secondly, regarding the back-translation process, we invited two teachers majoring in English who had never been exposed to these two scales before to back-translate the initial Chinese scale into English. Subsequently, we conducted a sentence-by-sentence comparison to ensure that there were no obvious deviations between the back-translated scale and the original scale. All variables were scored on a Likert scale, in which context “1” indicated complete disagreement and “7” indicated complete agreement. The specific measurement items of each variable are shown in Appendix A Table A1.

Enterprise–user interaction (EUI): The scale developed by Guo R.P. et al. [18], which featured a total of eight items and exhibited an internal consistency coefficient of 0.864, was used in this research.

Business model resilience (BMR): The scale developed by Kantur and Say [6], which featured a total of four items and exhibited an internal consistency coefficient of 0.865, was used in this research.

Enterprise dynamic capability (EDC): The scale developed by Li D.Y. et al. [8], which featured a total of 16 items and exhibited an internal consistency coefficient of 0.927, was used in this research.

Knowledge-oriented leadership (KOL): The scale developed by Donate and de Pablo [22], which featured a total of six items and exhibited an internal consistency coefficient of 0.855, was used in this research.

Control variables: Drawing on previous research, variables such as the prior experience of enterprise managers, the scale of the enterprise, the number of years since its establishment, industry type, and ownership attributes can influence its business model [5,40]. Therefore, in this study, educational (ED), enterprise size (ES), enterprise life (EL), enterprise region (ER), and enterprise industry (EI) were included as control variables.

3.3. Reliability and Validity

In terms of assessing the reliability of the measurement model, the SPSS 27.0 software was employed. Table 2 presents the results of the reliability and validity tests for each variable. As shown in Table 2, the Cronbach’s α coefficient values and composite reliability (CR) values of all variables exceeded 0.7, exceeding the international general standard, indicating that the questionnaire has good reliability.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity.

In terms of assessing the validity of the measurement model, the AMOS 28.0 software was employed. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to fit-test the measurement model composed of four variables. As presented in Table 3, the results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicate that the goodness-of-fit indices of the four-factor model () reached a favorable fitting effect and were superior to those of other models. In addition, in order to better test the issue of common method bias, we added a common method factor to construct a five-factor model based on the four-factor model consisting of EUI, EDC, BMR, and KOL. The results showed that the improvement in the indicators such as CFI and RMSEA of the five-factor model was limited, and neither of them exceeded 0.02. This indicates that the common method bias does not pose a threat. Furthermore, as shown in Table 2, the standardized factor loading coefficients of all variables exceeded 0.6, and the average variance extraction (AVE) value for each variable was above 0.4. When combined with the results presented in Table 4, it was evident that the square roots of the AVE values were significantly larger than the correlation coefficients among the variables. These findings collectively indicate the presence of good discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

The mean, standard deviation (SD), and correlation coefficient of each variable are shown in Table 4. A significant positive correlation between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience (), a significant negative correlation between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability (), and a significant negative correlation between enterprise dynamic capability and business model resilience () were observed. These results thus preliminarily met our theoretical expectations.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

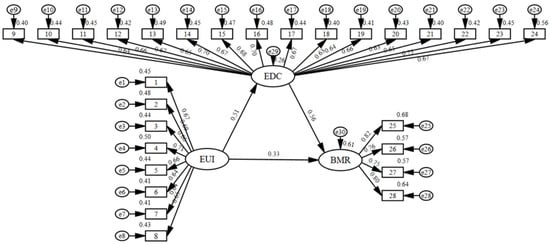

4.2.1. Test of the Main Effect and Intermediate Effect

A common sophisticated method was used to examine the direct impact of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience as well as the mediating effect of enterprise dynamic capability on the relationship between these two factors, thereby testing H1, H2, H2a, and H2b, and a structural equation model of the relationships among the three variables was constructed, as shown in Figure 2. The goodness-of-fit index of the structural equation model was , which meets international standards and proved that the model exhibited a good fit. Figure 2 indicates that the path coefficient pertaining to the impact of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience was 0.33 (), thus indicating that enterprise–user interaction has a positive impact on business model resilience; H1 was therefore supported. The path coefficient pertaining to the impact of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability was 0.51 (), thus indicating that enterprise–user interaction has a positive impact on enterprise dynamic capability; H2a was therefore supported. The path coefficient pertaining to the impact of enterprise dynamic capability on business model resilience was 0.56 (), thus indicating that enterprise dynamic capability has a positive impact on business model resilience; H2b was therefore supported. In light of these results, enterprise dynamic capability plays a mediating role in the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience, H2 was therefore supported.

Figure 2.

Best fit model.

To enhance the rigor of this research, we further tested the hypothesis discussed above using the methods developed by Hayes et al. Taking educational (ED), enterprise size (ES), enterprise life (EL), enterprise region (ER), and enterprise industry (EI) as control variables, with Bootstraps set to 5000 and a 95% confidence interval, the mediating role of enterprise dynamic capability was further examined. The results are presented in Table 5, and the results indicate that the mediating effect of enterprise dynamic capability is significant, with an effect size of 0.226, accounting for 39.09% of the total effect.

Table 5.

The mediating effect of EDC.

In addition, out of considerations for rigor, we adopted the mediating effect testing method proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) to further clarify the mediating role of EDC [41]. The regression results are shown in Table 6. It can be seen that EUI has a significantly positive impact on BMR (β = 0.539, t = 11.040, p < 0.001), and EUI also has a significantly positive impact on EDC (β = 0.465, t = 9.059, p < 0.001). After controlling for EUI, EDC still has a significantly positive impact on BMR (β = 0.511, t = 10.979, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, the direct effect of EUI on BMR decreases but remains significant (β = 0.301, t = 6.469, p < 0.001). This result indicates that EDC plays a partial mediating role between EUI and BMR, with the mediating effect size being 0.238 (0.465 × 0.511), accounting for approximately 44.2% of the total effect. The results of the two mediating effect tests further support Hypothesis 2.

Table 6.

Mediating effect result.

4.2.2. Test of the Moderating Effect

This study adopted a hierarchical regression approach to test the moderating effect of knowledge-oriented leadership on the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability. Firstly, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values of each model were examined to rule out the impact of multicollinearity. The results showed that the VIF values of all models were below 1.650, which is lower than the international general standard of 10. This indicates that there is no serious multicollinearity problem in this study. Secondly, enterprise–user interaction and knowledge-oriented leadership were centered, and an interaction term was constructed. Finally, regression analysis was carried out step by step. The regression results are presented in Table 7. M1 tested the impact of control variables on enterprise dynamic capability. After controlling for the control variables, M2, based on M1, tested the direct impacts of enterprise–user interaction and knowledge-oriented leadership on enterprise dynamic capability. The results showed that the explanatory effect of M2 was significant (, ). M3, on the basis of M2, added the impact of the interaction term between enterprise–user interaction and knowledge-oriented leadership on enterprise dynamic capability. The results indicated that knowledge-oriented leadership strengthened the positive impact of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability (, , ), and Hypothesis H3 was supported.

Table 7.

The hierarchical regression results of the moderating effect of knowledge-oriented leadership.

In addition, to ensure research rigor, we used Process Model 1 to estimate the moderating effect of knowledge-oriented leadership on the relationship between EUI and EDC at different values within the 95% confidence interval, with the number of Bootstraps set to 5000. The results are shown in Table 8. As presented in Table 8, at a low level of knowledge-oriented leadership (mean minus one standard deviation), the effect value of the EUI→EDC path was 0.209 (95% CI: [0.101, 0.317]); at a high level (mean plus one standard deviation), the effect value increased to 0.478 (95% CI: [0.341, 0.615]). Neither confidence interval included zero. These results demonstrate a significant difference in the strength of the EUI–EDC relationship across different levels of knowledge-oriented leadership. This shows that KOL positively moderates the relationship between EUI and EDC, and Hypothesis H3 is supported.

Table 8.

Regression results of the moderating effect of knowledge-oriented leadership.

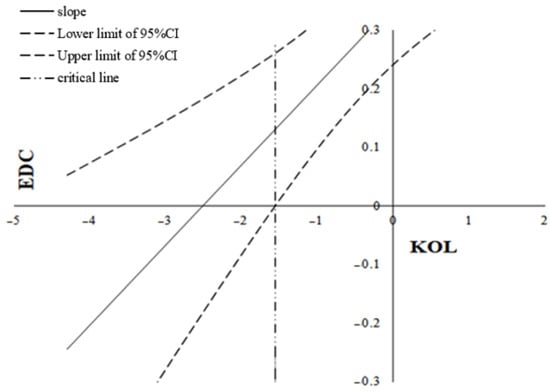

To present the moderating effect of knowledge-oriented leadership on the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability more intuitively and rigorously, this study plotted a Johnson–Neyman plot for the moderating effect of knowledge-oriented leadership between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability, as shown in Figure 3. When knowledge-oriented leadership is to the right of the critical value of −1.56, both the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval exclude 0, and the simple slope line is consistently above the X axis. This indicates that knowledge-oriented leadership positively moderates the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability. This result further supports Hypothesis H3.

Figure 3.

The moderating role of knowledge-oriented leadership.

4.2.3. Test of the Moderated Mediation Effect

Finally, this study utilized the Monte Carlo method to test the moderated mediation effect [42], namely Hypothesis H4. The Process macro in SPSS 27.0 was employed to calculate whether the mediation effect of knowledge-oriented leadership at different values was significant within the 95% confidence interval, with Bootstraps set to 5000. The results are presented in Table 9. As shown in Table 9, at a low level of knowledge-oriented leadership (mean minus one standard deviation), the indirect effect of the path “enterprise–user interaction → enterprise dynamic capability → business model resilience” was 0.102, with a 95% confidence interval of [−0.006, 0.228], which contained zero. Conversely, at a high level of knowledge-oriented leadership (mean plus one standard deviation), this indirect effect increased to 0.261, and the 95% confidence interval was [0.114, 0.405], excluding zero. This indicates that the indirect effect of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience through enterprise dynamic capability changes from being non-significant to significant. In essence, knowledge-oriented leadership moderates the mediating role of enterprise dynamic capability in the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience, thereby supporting Hypothesis H4.

Table 9.

Analysis results of the moderated mediating effects.

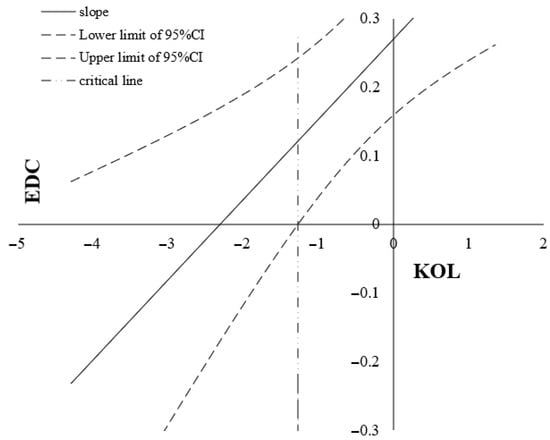

To further explain the moderated mediation effect, this study utilized the Johnson–Neyman plot to display the effects of knowledge-oriented leadership under different conditions and their significance levels. Figure 4 depicts that, when the value of knowledge-oriented leadership is to the right of the critical value of −1.281, both the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval exclude 0, and the simple slope line remains consistently above the X axis. This indicates that knowledge-oriented leadership has a positive moderating effect. It moderates the indirect effect of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience through enterprise dynamic capability. This finding further validates Hypothesis H4.

Figure 4.

The result of the moderated mediating effect.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Findings

Based on the dynamic capability theory and from the perspective of enterprise–user interaction, this study aims to explore the internal logic and mechanism through which enterprise–user interaction influences the business model resilience. It mainly probes into the three following research questions: Firstly, how does enterprise–user interaction affect business model resilience? Secondly, can enterprise dynamic capability play a mediating role between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience? Thirdly, what role does knowledge-oriented leadership play in the above-mentioned influence mechanism? Starting from the three research questions of this study, we conduct questionnaire surveys through both online and offline methods, and comprehensively apply a variety of empirical methods. Using data from 300 enterprise questionnaires as a sample, we empirically test the relationships among enterprise–user interaction, enterprise dynamic capability, business model resilience, and knowledge-oriented leadership. The empirical results show that enterprise–user interaction has a positive impact on business model resilience; enterprise dynamic capability plays a partial mediating role in the process of influencing enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience; knowledge-oriented leadership plays a moderating role, positively moderating the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability, as well as the indirect effect of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience through enterprise dynamic capability. Specifically, enterprise–user interaction enables enterprises to acquire a large amount of rich user information and resources, thereby enhancing their ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources, namely enterprise dynamic capability. The improvement in enterprise dynamic capability, in turn, promotes the enhancement of business model resilience. In other words, enterprise dynamic capability serves as a mediating mechanism between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience. Knowledge-oriented leadership, as a new-style leadership, acts as a moderating mechanism in the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability and its mediating role. Under the influence of a high-level knowledge-oriented leadership, both the relationship between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability and the indirect effect of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience through enterprise dynamic capability are strengthened. This empirical result not only answers the research questions of this study, but also, from an academic perspective, offers practical guidance to enterprises on how to effectively enhance business model resilience through enterprise–user interaction.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

Firstly, this study, from the perspective of multi-agent interaction between enterprises and users, explored the influence mechanism of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience and conducted empirical tests, which is conducive to promoting research on the antecedents of business model resilience. Existing research suggests that the influencing factors of business model resilience can be classified into three aspects: individual, organizational, and external environment [17]. For instance, Niemimaa et al. posited that unexpected external environmental events can impact and disrupt the business model resilience of enterprises [5]. Regrettably, few studies have probed into the influence of the relationship between individuals and organizations on business model resilience. Even if there are such studies, they mostly adopt qualitative research methods. This blurs the theoretical explanation and testing of enterprise–user interaction, weakening the internal mechanism of enterprise–user interaction and reducing its universality. In view of this, this study took the perspective of multi-agent interaction between enterprises and users to explore the influence mechanism of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience and carried out empirical verification. The study found that enterprise–user interaction can bring diverse user knowledge and resources to enterprises, thereby helping enterprises continuously optimize the underlying logic of the business model and ultimately enhance business model resilience. This research result expands the findings of Li H.L. and Wang B.C. et al. from the empirical perspective of the interaction relationship between individuals and organizations rather than the construction perspective [2,20], further enriching the research on the antecedents of business model resilience.

Secondly, based on the dynamic capability theory, this study examined the mediating role of enterprise dynamic capability in the process of how enterprise–user interaction affects business model resilience. This not only deepens the explanatory power of the dynamic capability theory in the research of business model resilience, but also empirically explores the source of enterprise dynamic capability. Scholars such as Teece and Pisano believe that exploring the source of enterprise dynamic capability and how to improve them are important issues in management research [7,32]. Reviewing existing research, organizational resources are regarded as an important source of enterprise dynamic capability [43]. Dentoni et al., from the perspective of enterprise stakeholders, pointed out that, if an enterprise can interact effectively with its stakeholders, it can obtain more heterogeneous resources from the perspective of stakeholders and accurately perceive their needs, and then adjust the enterprise’s resource base and business processes, thereby improving enterprise dynamic capability [44]. However, regrettably, as one of the most important stakeholders of an enterprise, few studies have started from the user perspective and used quantitative methods to explore how enterprises can obtain heterogeneous resources from the interaction with users and transform them into dynamic capability advantages. Based on this, this study, from the perspective of enterprise–user interaction, theoretically and empirically tested that the heterogeneous resources obtained through enterprise–user interaction help enterprises continuously update their resource base in the dynamic process and thus improve the enterprise’s dynamic capability. This conclusion actually expands the view of Dentoni et al. that the interaction process between enterprises and stakeholders helps enhance enterprise dynamic capability [44], and enriches the impact of enterprise dynamic capability from the perspective of business model resilience. At the same time, the resource interaction mechanism between enterprises and users proposed in this study also plays a certain role in promoting the further development of relevant research on the dynamic capability theory.

5.3. Practical Implications

Firstly, enterprise–user interaction serves as a crucial mechanism for enhancing an enterprise’s business model resilience in the knowledge economy. In the context of management practice, enterprises are advised to recognize enterprise–user interaction as a pivotal strategy for enhancing business model resilience, given its significance in the contemporary business landscape. Enterprises should leverage diverse online and offline channels to deepen user engagement and ensure interaction quality and efficiency. Furthermore, enterprises should efficiently utilize the heterogeneous resources obtained from enterprise–user interaction according to their actual development status. By integrating these resources into the business model’s core logic, enterprises can construct a more flexible and resilient business model, thereby enhancing their adaptability to market changes. These resources should be treated as crucial elements for updating the underlying logic of the business model. In addition, enterprises should continuously adjust their business models and operating strategies in response to external environmental changes. This proactive approach helps reduce the interference and impact of sudden crisis events on the business model, thus maximizing the contribution of enterprise–user interaction to business model resilience.

Secondly, enterprise dynamic capability plays a mediating role in the impact of enterprise–user interaction on business model resilience. In a rapidly changing business environment, dynamic capability is the key capability that help enterprises form sustainable competitive advantages and ensure the efficient and continuous operation of their business models. Enterprise managers should attach great importance to the cultivation and enhancement of enterprise dynamic capability. In management practice, enterprises should maintain a high degree of sensitivity to external environmental changes and quickly acquire heterogeneous resources during the interaction with users. Subsequently, they should rapidly integrate and efficiently allocate internal and external resources based on their actual development status, thereby continuously updating and reconstructing the enterprise’s resource base. In the continuous interaction with users, the enterprise should also continuously upgrade its dynamic capability.

Thirdly, as a new-style leadership, knowledge-oriented leadership plays an important promoting role in the impact of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability and business model resilience. Enterprise leaders should deeply understand the core driving role of the integration and allocation of heterogeneous knowledge resources in improving enterprise dynamic capability and establishing and maintaining sustainable competitive advantages. In management practice, enterprise leaders should clearly express their recognition and emphasis on knowledge resources, regard heterogeneous knowledge resources as the core driving force for enterprise development, and create a favorable atmosphere within the organization to encourage employees to actively engage in the integration and allocation of heterogeneous knowledge resources. This can accelerate the rapid integration and efficient allocation of knowledge resources by the enterprise, so as to better exert the promoting effect of enterprise–user interaction on enterprise dynamic capability and business model resilience.

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Firstly, the exploration of enterprise dynamic capability is rather general, lacking depth and refinement. The dimensions of enterprise dynamic capability have not been differentiated. Follow-up research, building upon our study, can further distinguish the different dimensions of enterprise dynamic capability and explore in more detail the mediating role of each dimension between enterprise–user interaction and business model resilience. Secondly, this study focused on the moderating role of knowledge-oriented leadership, a contemporary leadership paradigm, between enterprise–user interaction and enterprise dynamic capability, arguing that knowledge-oriented leadership can effectively accelerate the integration and allocation process of enterprise knowledge resources. However, beyond the moderating role of knowledge-oriented leadership, other mechanisms may significantly influence the integration and allocation of enterprise knowledge resources. In the future, from the perspective of enterprise organizational structure characteristics and other aspects, it is possible to explore the moderating effect of the integration and allocation of enterprise knowledge resources on external resource acquisition channels and enterprise dynamic capability. For example, a distributed organizational structure can better share knowledge resources, thus enriching and expanding the boundary conditions of the dynamic capability theory. Thirdly, constrained by research conditions, this study solely relied on questionnaires for data collection. Moreover, it failed to conduct a detailed classification of interviewees’ positions, functional roles, decision-making authority, and organizational departments. In the future, experimental methods can be adopted, or longitudinal tracking data can be obtained from multiple time points and multiple sources. Moreover, the specific positions of the interviewees should be further subdivided to reduce the impact of the subjective cognitive biases of the interviewees and further verify the relationships among various variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; software, W.T.; validation, H.Z., and W.T.; formal analysis, H.Z. and W.T.; investigation, W.T.; resources, H.Z. and X.S.; data curation, W.T.; writing—original draft preparation, W.T.; writing—review and editing, H.Z.; visualization, H.Z.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, H.Z. and X.S.; funding acquisition, H.Z. and X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 72102062, 72332001) and National Social Science Fund of China (Grant number: 24&ZD080).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval for the present study was granted by Business School, Henan Normal University. All research was performed in accordance with regulations specified in the ethics approval and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement items.

Table A1.

Measurement items.

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| EUI | 1. Distribute questionnaires (via email) to users to understand the opinions and feelings of different types of users regarding the product usage and functions. | 0.672 |

| 2. Utilize various social platforms (such as Weibo, Douyin, Tieba, Zhihu, app stores, etc.) to conduct extensive interactions with users, discuss product usage, and collect suggestions. | 0.695 | |

| 3. Set up interactive feedback designs (such as comments and replies) within the functions of this product to collect user feedback. | 0.660 | |

| 4. Extensively understand the needs of different types of users through third-party data platforms (such as Baidu Index, TalkingData, etc.). | 0.711 | |

| 5. Recruit a certain number of interviewed users and conduct in-depth interviews at the users’ homes, laboratories, or other relevant scenarios to advance the demand collection work. | 0.667 | |

| 6. Invite senior users to participate in an in-depth product experience and put forward suggestions regarding the product. | 0.641 | |

| 7. By analyzing different user data, establish user data dashboards and user tags, and push personalized information to different types of users. | 0.636 | |

| 8. Establish data tracking points in the product function design to collect and analyze users’ behavioral data, and confirm the product version that is more popular among users through A/B testing. | 0.652 | |

| EDC | 1. The company can detect environmental changes ahead of most competitors. | 0.634 |

| 2. The company often holds inter-departmental meetings to discuss the market demand situation. | 0.662 | |

| 3. The company can correctly understand the impact of internal and external environmental changes on the enterprise. | 0.668 | |

| 4. The company can identify potential opportunities and threats from environmental information. | 0.645 | |

| 5. The company has a relatively complete information management system. | 0.701 | |

| 6. The company has strong judgment and insight into the market. | 0.668 | |

| 7. The company can quickly handle various conflicts in the strategic decision-making process. | 0.683 | |

| 8. In many cases, the company can make decisions to deal with strategic issues immediately. | 0.696 | |

| 9. The company can accurately reposition the market according to environmental changes. | 0.665 | |

| 10. When we find that customers are dissatisfied, we will immediately take corrective measures. | 0.632 | |

| 11. The company can quickly recombine resources to adapt to environmental changes. | 0.639 | |

| 12. The company’s strategy can be effectively decomposed and implemented. | 0.659 | |

| 13. There is good cooperation among different execution departments. | 0.631 | |

| 14. When implementing the departmental strategy, assistance can be obtained from other relevant departments. | 0.651 | |

| 15. The degree of achievement of strategic objectives is combined with individual rewards and punishments. | 0.672 | |

| 16. The enterprise can effectively track the implementation effect. | 0.748 | |

| BMR | 1. The business model of the enterprise is robust: It can directly confront crises and ensure that the enterprise’s production is not damaged. | 0.822 |

| 2. The business model of the enterprise is resilient: It can react quickly and respond flexibly after being damaged. | 0.754 | |

| 3. The business model of the enterprise is redundant: It reflects the degree of surplus of capabilities and resources after responding to crises. | 0.755 | |

| 4. The business model of the enterprise is characterized by rapidity: After encountering a crisis, the business model can recover quickly and achieve continuous growth. | 0.808 | |

| KOL | 1. Leadership has been creating an environment for responsible employee behavior and teamwork. | 0.759 |

| 2. Managers are used to assuming the role of knowledge leaders, which is mainly characterized by openness, tolerance of mistakes and mediation for the achievement of the firm’s objectives. | 0.710 | |

| 3. Managers promote learning from experience, tolerating mistakes up to a certain point. | 0.632 | |

| 4. Managers behave as advisers, and controls are just an assessment of the accomplishment of objective. | 0.660 | |

| 5. Managers promote the acquisition of external knowledge. | 0.765 | |

| 6. Managers reward employees who share and apply their knowledge. | 0.711 |

References

- Xiao, J.H.; Hu, Y.S.; Wu, Y. Evolving Product: A Case Study of Data-Driven Enterprise and User-Interactive Innovation. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 183–205. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L. Business Model Resilience in Major Emergencies: A Pair-case Study of Business Continuity Evaluation Based on Network Theory. Bus. Manag. J. 2023, 45, 91–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Barasa, E.; Mbau, R.; Gilson, L. What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. Int. J. Health Policy 2018, 7, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemimaa, M.; Järveläinen, J.; Heikkilä, M.; Heikkilä, J. Business continuity of business models: Evaluating the resilience of business models for contingencies. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2019, 49, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantur, D.; Say, A.I. Measuring organizational resilience: A scale development. J. Bus. Econ. Financ. 2015, 4, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Xiang, B.H.; Chen, Y.L. Dynamic Capabilities and Their Functions: The Impact of Perceived Environmental Uncertainty. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2009, 12, 60–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augier, M.; Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and multinational enterprise: Penrosean insights and omissions. Manag. Int. Rev. 2007, 47, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.B.; Ge, B.S.; Wang, K. Resource Integration Process, Dynamic Capability and Competitive Advantage: Mechanism and Path. J. Manag. World 2011, 03, 92–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Giudici, A.; Reinmoeller, P.; Ravasi, D. Open-system orchestration as a relational source of sensing capabilities: Evidence from a venture association. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1369–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Applicability of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views under environmental volatility. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ouyang, T.H.; Huang, J.M. Research on How Smart Connected Products Reshape Enterprise Boundaries: The Case of Xiaomi. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 125–142. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cui, A.S.; Wu, F. Utilizing customer knowledge in innovation: Antecedents and impact of customer involvement on new product performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 516–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.C.; Hao, X.l.; Jiang, A.P. Multiple Realization Paths of Business Model Resilience from the Perspective of Knowledge. J. Stat. Inf. 2021, 36, 106–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.P.; Feng, Z.Q.; Gong, R.; Wang, Y. Enterprise-User Interaction, Agile Development, and Digital Product Innovation Performance. RD Manag. 2024, 36, 108–120. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, G.; Wei, K.; Chen, J. Spillover effects of interactions on user innovation: Evidence from a firm-hosted open innovation platform. Inform. Manag.-Amster 2024, 61, 103947. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.C.; Zhang, Y.X.; Cui, M.J. Research on the Impact of Digital Interaction on Business Model Innovation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 45, 136–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, X.G.; Li, X.C.; Fang, H.Y. Measurement and Efficacy of Dynamic Capability: An Empirical Study Based on Chinese Experience. J. Manag. World 2006, 03, 94–103+113+171. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Donate, M.J.; de Pablo, J.D.S. The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Knowledge-oriented leadership and open innovation: Role of knowledge management capability in France-based multinationals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business Models and Lean Startup. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 3183–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value creation in e-business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Zhao, W.H.; Kong, L.F.; Xiong, Z.; Gu, M. Cognitive Style, Entrepreneurial Resilience and Business Model Innovation in New Venture. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 135–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.; Krammer, S.M.S.; Pérez-Aradros, B.; Salazar, I. Resilience to the pandemic: The role of female management, multi-unit structure, and business model innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.C.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, X.L. Configuration Research on Business Model Innovation of Internet Service Companies: Based on a Strategy and Resource Perspective. J. Manag. 2022, 35, 119–135. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xe, K.; Hu, Y.S.; Xiao, J.H. Big Data-Driven Firm-User Interactive Innovation: Theoretical Framework and Cutting-Edge Topics. RD Manag. 2024, 36, 147–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkala, A.; Salminen, R.T. Practices and functions of customer reference marketing—Leveraging customer references as marketing assets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G. The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms: An Introduction. Ind. Corp. Chang. Corp. Change 1994, 3, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Wenger, L.; Pezeshkan, A.; Mallon, M.R. When do dynamic capabilities lead to competitive advantage? The importance of strategic fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 758–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Chang, Q.; Cui, L. Across the Organizational Hierarchy: A Study of the Dynamic Construction Mechanism of Enterprise Innovation Capability. Manag. Rev. 2019, 31, 287–300. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Ichikohji, T. How dynamic capabilities enable Chinese SMEs to survive and thrive during COVID-19: Exploring the mediating role of business model innovation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.T.; Lv, Z.Q.; Hu, X.H.; Xie, Z.Y. Big Data Analysis Capability, Dynamic Capability and Business Model Innovation for Manufacturing Enterprises:The Perspective of Resource Orchestration. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2024, 41, 107–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Buyukbalci, P.; Sanguineti, F.; Sacco, F. Rejuvenating business models via startup collaborations: Evidence from the Turkish context. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 174, 114521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Manu, D.; Edwards, D.J.; Pärn, E.A.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Aigbavboa, C. The knowledge enablers of knowledge transfer: A study in the construction industries in Ghana. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2018, 16, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Rad, F. The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management and innovation. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grego, M.; Magnani, G.; Denicolai, S. Transform to adapt or resilient by design? How organizations can foster resilience through business model transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 171, 114359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selig, J.P.; Preacher, K.J. Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation: An Interactive Tool for Creating Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects. Available online: http://quantpsy.org/medmc/medmc.htm (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Jiao, H.; Yang, J.F.; Ying, Y. Dynamic Capabilities: A Systematic Literature Review and An Agenda for the Chinese Future Research. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 191–210. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dentoni, D.; Bitzer, V.; Pascucci, S. Cross-sector partnerships and the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).