Cultural Heritage as a Catalyst for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: The Case of Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

Global Relevance of Tarout Island’s Case Study

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Regeneration

2.2. Heritage-Based Urban Regeneration

2.3. Case Studies on Heritage-Based Urban Regeneration

2.3.1. Global Case Study: Preserving the Historic Center of Malaga, Spain

2.3.2. Regional Case Study: The Historic Old Saida, Lebanon

2.3.3. Local Case Study: Historic Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2.3.4. A Comparative Analysis of Heritage-Based Urban Regeneration Case Studies

2.3.5. Lessons Learned and Global Applicability

3. Materials and Methods

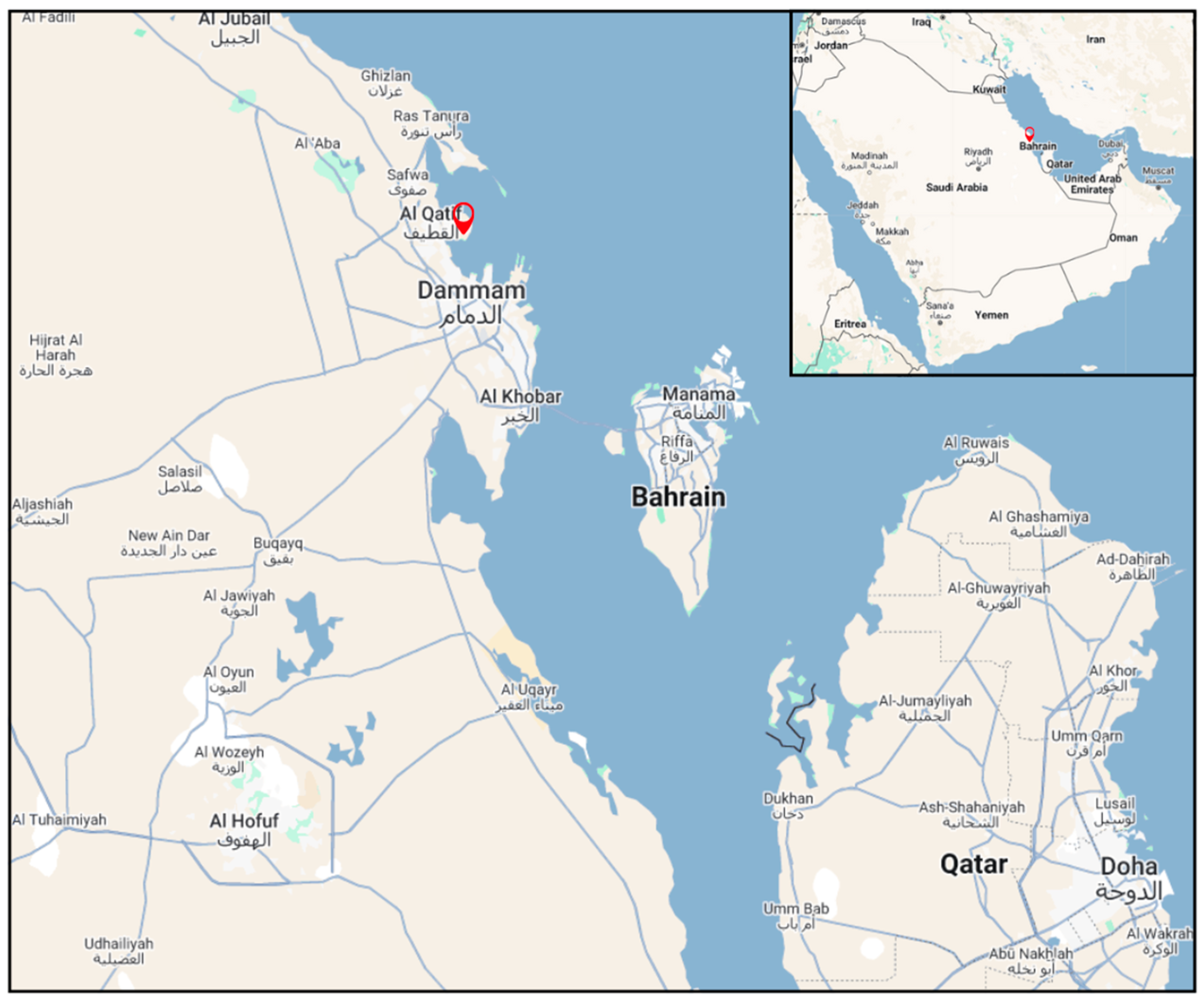

4. Tarout Island: A Legacy of History, Culture, and Challenges

4.1. Ancient History and Trade Significance

4.2. Islamic Era and Cultural Evolution

4.3. Historical Landmarks and Architecture

4.4. Socio-Economic Landscape

4.5. Urbanization and Infrastructure Challenges

4.6. Environmental Concerns and Climate Impact

4.7. Heritage Conservation Challenges

5. Discussion

5.1. The Role of Heritage-Based Urban Regeneration in Tarout Island

5.2. Sustainable Tourism as a Tool for Economic Development

5.3. Community Involvement in Regeneration Planning

- Community Co-Design Workshops: Regular workshops using HCD methods like brainstorming, persona development, and prototyping to involve residents in designing heritage trails, public spaces, and adaptive reuse projects. For example, workshops could focus on co-creating heritage trails that highlight local stories, ensuring cultural authenticity.

- Digital Feedback Platforms: Online portals or mobile apps for residents to provide continuous feedback on regeneration projects, with iterative updates based on community input. These platforms can use HCD’s journey mapping to track resident experiences and identify pain points in the regeneration process.

- Citizen Advisory Panels: Permanent resident-led panels to monitor and guide regeneration efforts, ensuring sustained input. HCD’s stakeholder mapping can ensure the representation of diverse groups, such as youth, artisans, and elders, to address varied needs.

- Empathy Mapping Exercises: Conduct sessions to understand residents’ emotional and cultural attachments to Tarout’s heritage, informing sensitive planning decisions. For instance, empathy maps could reveal preferences for preserving traditional markets, guiding adaptive reuse plans.

5.4. Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Structures for Economic and Cultural Revitalization

5.5. Integrating Environmental Sustainability into Regeneration Efforts

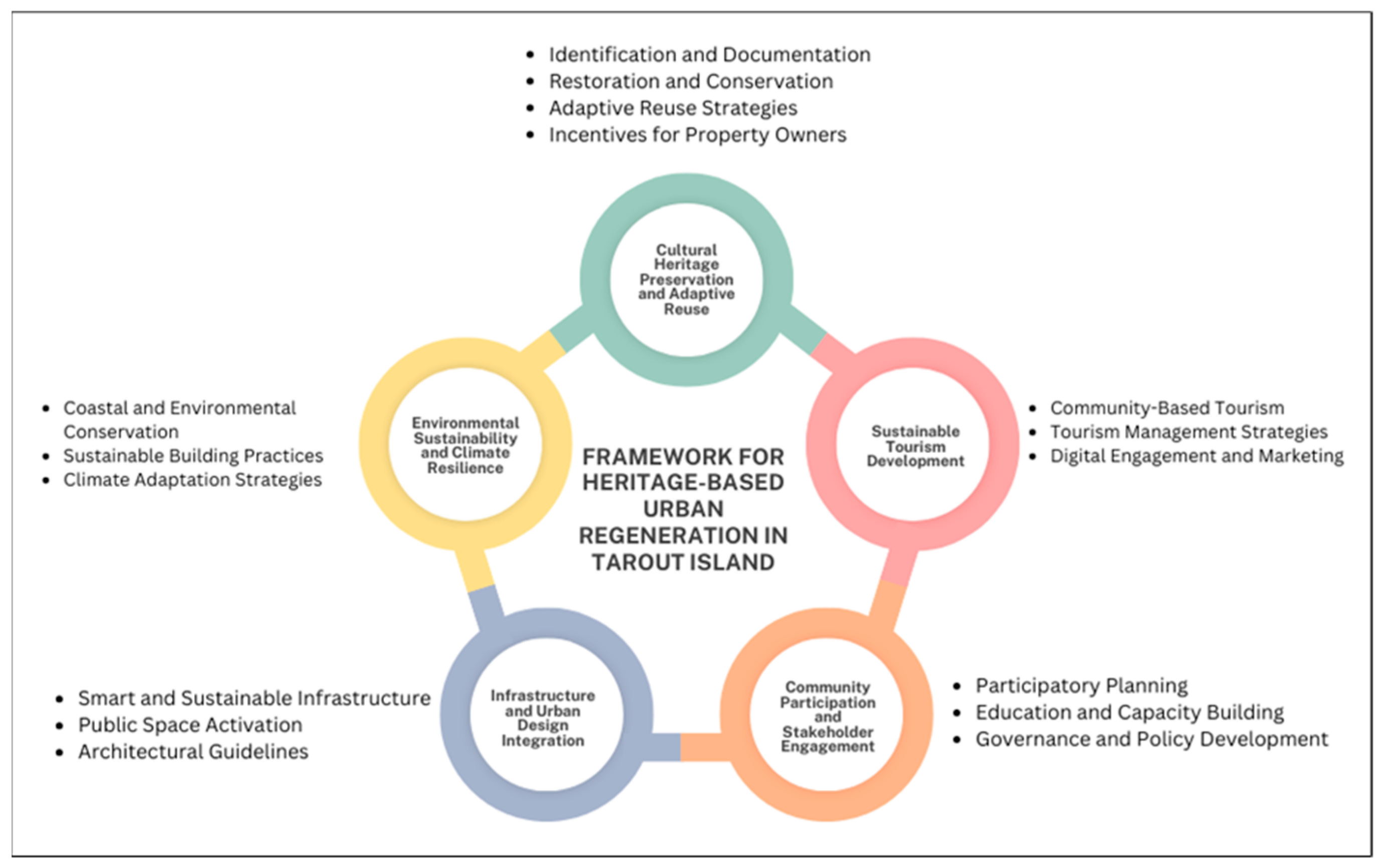

6. Proposed Framework for Heritage-Based Urban Regeneration in Tarout Island

6.1. Key Components of the Proposed Framework

6.1.1. Cultural Heritage Preservation and Adaptive Reuse

6.1.2. Sustainable Tourism Development

6.1.3. Community Participation and Stakeholder Engagement

6.1.4. Infrastructure and Urban Design Integration

6.1.5. Environmental Sustainability and Climate Resilience

6.2. Implementation Strategy

6.2.1. Short-Term Initiatives (1–3 Years)

6.2.2. Medium-Term Goals (3–7 Years)

6.2.3. Long-Term Vision (7+ Years)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN-Habitat. Qatif City Profile; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Vision 2030; Saudi Arabia Government: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2016.

- Abou-Korin, A. Impacts of Rapid Urbanisation in the Arab World: The Case of Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia; University Sains Malaysia: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 2011; Volume 11800, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, C.; Balaban, O. Sustainability of Urban Regeneration in Turkey: Assessing the Performance of the North Ankara Urban Regeneration Project. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, T. Regeneration towards Suitability: A Decision-Making Framework for Determining Urban Regeneration Mode and Strategies. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeri, A.; Bortoli, G.; Longo, D. Cultural heritage as a driver for urban regeneration: Comparing two processes. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 217, 587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, B. A Blended Finance Framework for Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration. Land 2022, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Li, P.; Yan, J.; Wang, H. Systematic Review of Socially Sustainable and Community Regeneration: Research Traits, Focal Points, and Future Trajectories. Buildings 2024, 14, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, A. Urban Regeneration and Its Impact for Sustainable City Development. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference GEOBALCANICA 2020, Ohrid, North Macedonia, 12–14 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa, D. Urban Regeneration and the Search for Identity in Historic Cities. Sustainability 2017, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Dennemann, A. Urban Regeneration and Sustainable Development in Britain. Cities 2000, 17, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, B.; Giulia, D. Addressing Social Sustainability in Urban Regeneration Processes. An Application of the Social Multi-Criteria Evaluation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, J.; Jung, C. Extracting the Planning Elements for Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Dubai with AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.H. Finding Urban Identity through Culture-Led Urban Regeneration. J. Urban Manag. 2014, 3, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M. Urban History and Cultural Resources in Urban Regeneration: A Case of Creative Waterfront Renewal. Plan. Perspect. 2013, 28, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, P. Urban Regeneration: Is There a Future? People Place Policy Online 2010, 4, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Ou, Y. Urban Community Regeneration and Community Vitality Revitalization through Participatory Planning in China. Cities 2021, 110, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrıkul, A. The Role of Community Participation and Social Inclusion in Successful Historic City Center Regeneration in the Mediterranean Region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Li, L.; Ma, J.; Liu, D.; Li, J. A Study of Residents’ Intentions to Participate in the Renovation of Older Communities under the Perspective of Urban Renewal: Evidence from Zhangjiakou, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 1094–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulles, K.; Conti, I.A.M.; Kleijn, M.B.D.; Kusters, B.; Rous, T.; Havinga, L.C.; Ikiz Kaya, D. Emerging Strategies for Regeneration of Historic Urban Sites: A Systematic Literature Review. City Cult. Soc. 2023, 35, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardowli, M.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Aram, F.; Mosavi, A. Survey of Sustainable Regeneration of Historic and Cultural Cores of Cities. Energies 2020, 13, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, H. Sustainable Regeneration through the Cultural Conversion of Urban Heritage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Gheitasi, M.; Timothy, D.J. Urban Regeneration through Heritage Tourism: Cultural Policies and Strategic Management. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnokaly, A.; Elseragy, A. Sustainable Heritage Development: Learning from Urban Conservation of Heritage Projects in Non Western Contexts. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 2, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dogruyol, K.; Aziz, Z.; Arayici, Y. Eye of Sustainable Planning: A Conceptual Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration Planning Framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividade-Jesus, E.; Almeida, A.; Sousa, N.; Coutinho-Rodrigues, J. A Case Study Driven Integrated Methodology to Support Sustainable Urban Regeneration Planning and Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttormsen, T.S.; Skrede, J.; Guzman, P.; Fouseki, K.; Bonacchi, C.; Pastor Pérez, A. Assemblage Urbanism: The Role of Heritage in Urban Placemaking. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, M.; Rodrigues, E. A Heritage-Based Method to Urban Regeneration in Developing Countries: The Case Study of Luanda. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, R.; Nunes, M.C. Tackling Urban Disparities through Participatory Culture-Led Urban Regeneration. Insights from Lisbon. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippschild, R.; Zöllter, C. Urban Regeneration between Cultural Heritage Preservation and Revitalization: Experiences with a Decision Support Tool in Eastern Germany. Land 2021, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canesi, R.; D’Alpaos, C.; Marella, G. A Case of Local Community Engagement for Urban Regeneration: The South Boston Area. In Urban Regeneration Through Valuation Systems for Innovation; Abastante, F., Bottero, M., D’Alpaos, C., Ingaramo, L., Oppio, A., Rosato, P., Salvo, F., Eds.; Green Energy and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 217–228. ISBN 978-3-031-12813-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrar, S.; Wang, R. Towards an Inclusive Urban Regeneration: Community Engagement in India and China. AMPS Proc. Ser. 2024, 34, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Newman, G.; Jiang, B. Urban Regeneration: Community Engagement Process for Vacant Land in Declining Cities. Cities 2020, 102, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W. Collaborative Workshop and Community Participation: A New Approach to Urban Regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LUMA Institute (Ed.) Innovating for People: Handbook of Human-Centered Design Methods, 1st ed.; LUMA Institute, LLC: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-9857509-0-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.C.; Stiefel, B. (Eds.) Human-Centered Built Environment Heritage Preservation: Theory and Evidence-Based Practice; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-138-58394-8. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, G. Circular Economxy Strategies for Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage Buildings to Reduce Environmental Impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. Multiple Approaches to Heritage in Urban Regeneration: The Case of City Gate, Valletta. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-hagla, K.S. Sustainable Urban Development in Historical Areas Using the Tourist Trail Approach: A Case Study of the Cultural Heritage and Urban Development (CHUD) Project in Saida, Lebanon. Cities 2010, 27, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Forbici, S. Power to the People: When Culture Works as a Social Catalyst in Urban Regeneration Processes (and When It Does Not). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S.; Rahimzad, R.; Parsa, A. ‘Smart’ Sustainable Urban Regeneration: Institutions, Quality and Financial Innovation. Cities 2015, 48, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouseki, K.; Nicolau, M. Urban Heritage Dynamics in ‘Heritage-Led Regeneration’: Towards a Sustainable Lifestyles Approach. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2018, 9, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, S. Urban Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula, the Experiences of Jeddah and Dubai. Built Herit. 2018, 2, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Escampa, M.; Barrera-Fernández, D. The Impact of European Programmes on Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration Initiatives in the Historic Centre of Malaga. In Urban Regeneration in Europe; Altrock, U., Kurth, D., Eds.; Jahrbuch Stadterneuerung; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 235–266. ISBN 978-3-031-64772-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sahahiri, R.; Arrowsmith, C.; Alitany, A.A. Mapping the Historical Places: A Case Study of Promoting Tourism in Jeddah, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2019, 6, 1691315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, C.N.; Eze Val, H.U. Qualitative Research. IDOSR J. Comput. Appl. Sci. 2023, 8, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Makateng, D.S.; Mokala, N.T. Understanding Qualitative Research Methodology: A Systematic Review. E-J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. 2025, 6, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaissi, A. Exploring Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research: In Advances in Data Mining and Database Management; Bentalha, B., Alla, L., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 253–294. ISBN 979-8-3693-8689-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jabr, M.; Al-Salmi, A. Usus al-hifaz “ala al-taabi” al-mahali lil-bi’ah al-kharijiyah fi al-madina al-arabiya al-taqlidiyah: Qaryat Darin, Jazirat Tarout, al-Mamlakah al-Arabiyah al-Saudiyah [Principles of Preserving the Local Character of the External Environment in the Traditional Arab City: Darin village, Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia]. Conference on the Role of Engineering Towards a Better Environment: Continuous Development. 1999, pp. 803–821. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327702163 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Alaqeel, M. Features of Life in the Neolithic Sites in Saudi Arabi’s Eastren Region. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. PJLSS 2024, 22, 19137–19154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, N. Empowering Economic Development by Promoting Saudi Arabia’s Cultural Heritage. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.A. Sea of Pearls: Seven Thousand Years of the Industry That Shaped the Gulf; Arabian: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-9571060-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- Avanzini, A. Eastern Arabia in the First Millenium BC; Avanzini, A., Ed.; Arabia antica; “L’Erma” di Bretschneider: Roma, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-88-8265-568-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sampieri, S.; Bagader, M. Sustainable Tourism Development in Jeddah: Protecting Cultural Heritage While Promoting Travel Destination. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tatar, S. Yaeud Tarikhuha 'Iilaa 'Akthar Min 5 Aalif Eam Qabl Almilad: Jazirat Tarut Wa Qaleatuha Alshahiratu.. Manarat Jadhb Lilsuyaah Min Aldaakhila. Walkharij. [Dating back more than 5,000 years BC: Tarout Island and its famous castle... a beacon that attracts tourists from both inside and outside the country]. Al Yamamah 2023, 2762, 8–11. Available online: https://alyamamahonline.com/storage/issues/pdf/pdf/2762/2762.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Salam, Y. Jazirat Tarut Eabr Altaarikh [Tarout Island throughout history]. Qafilah 1972, 20, 11–19. Available online: https://qafilah.com/ar/issue/221/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Babsail, M.O.; Al-Qawasmi, J. (Eds.) Vernacular Architecture in Saudi Arabia: Revival of Displaced Traditions. In Vernacular Architecture: Towards a Sustainable Future; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 119–124. ISBN 978-0-429-22679-3. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaim, M.M. Understanding the Traditional Saudi Built Environment: The Phenomenon of Dynamic Core Concept and Forms. World J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 292–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. The Saudi ‘Social Contract’ Under Strain: Employment and Housing. POMEPS Stud. 2018, 31, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs, G.; Reguero, B.G. Coastal Adaptation to Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise. Water 2021, 13, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehaby, F. Assessing the Legal Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Saudi Arabia: A Critical Analysis in the Context of the 2003 UNESCO Convention. Laws 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.G.M.; Elsheikha, A.A.A.; Elbanna, E.M.; Peinado, F.J.M. An Approach to Conservation and Management of Farasan Islands’ Heritage Sites, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2018, 9, 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sorogy, A.S.; Youssef, M.; Al-Kahtany, K. Integrated Assessment of the Tarut Island Coast, Arabian Gulf, Saudi Arabia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Mariano, C.; Perrone, F. Cultural Heritage Recognition through Protection of Historical Value and Urban Regeneration: CSOA Forte Prenestino. Land 2024, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, Z. Contested Memory amidst Rapid Urban Transition: The Cultural Politics of Urban Regeneration in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2020, 102, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhou, Y. Conducting Heritage Tourism-Led Urban Renewal in Chinese Historical and Cultural Urban Spaces: A Case Study of Datong. Land 2022, 11, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkin, C. Beyond the Rhetoric: Negotiating the Politics and Realising the Potential of Community-driven Heritage Engagement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D.; Petetskaya, K. Heritage-Led Urban Rehabilitation: Evaluation Methods and an Application in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 26, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lu, Y.; Martin, J. A Review of the Role of Social Media for the Cultural Heritage Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Hoeven, A. Historic Urban Landscapes on Social Media: The Contributions of Online Narrative Practices to Urban Heritage Conservation. City Cult. Soc. 2019, 17, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfa, F.H.; Zijlstra, H.; Lubelli, B.; Quist, W. Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings: From a Literature Review to a Model of Practice. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2022, 13, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive Reuse Strategies for Heritage Buildings: A Holistic Approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-belkasy, M.I.; Wahieb, S.A. Sustainable Conservation and Reuse of Historical City Center Applied Study on Jeddah—Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnokaly, A.; Elseragy, A. Sustainable Urban Regeneration of Historic City Centres–Lessons Learnt. In Proceedings of the World Sustainable Building Conference; Finnish Association of Civil Engineers RIL: Helsinki, Finland, 2011; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.M.; Yun, B.Y.; Yang, S.; Wi, S.; Chang, S.J.; Kim, S. Optimal Energy Retrofit Plan for Conservation and Sustainable Use of Historic Campus Building: Case of Cultural Property Building. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J. Mangrove Management for Climate Change Adaptation and Sustainable Development in Coastal Zones. J. Sustain. For. 2018, 37, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Study | Objectives | Methods | Challenges | Sustainability Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaga, Spain | Revitalize historic center, boost tourism | Adaptive reuse, pedestrianization, cultural investments | Gentrification, resident displacement | Economic growth, cultural hub, but social inequities |

| Old Saida, Lebanon | Preserve historic core, promote tourism | Heritage trail, artisan integration, site restoration | Limited infrastructure, uneven community benefits | Cultural preservation, tourism growth, but local exclusion |

| Historic Jeddah, Saudi Arabia | Restore UNESCO site, align with Vision 2030 | Adaptive reuse, pedestrian zones, cultural tourism | Funding constraints, resident resistance | Heritage preservation, tourism boost, national alignment |

| Luanda, Angola | Integrate heritage into urban planning | Heritage Set mapping, mixed-use development | Weak legal enforcement, low public awareness | Economic growth, community cohesion, ongoing conservation |

| Famagusta, Northern Cyprus | Preserve coastal heritage, enhance community identity | Community workshops, eco-friendly restoration, heritage trails | Funding shortages, land use conflicts | Cultural identity, environmental resilience, tourism appeal |

| Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia | Preserve cultural heritage, promote sustainable development | Adaptive reuse, community co-design, eco-tourism, mangrove conservation | Weak legal enforcement, funding constraints, over-commercialization risks | (Proposed) cultural preservation, community empowerment, environmental resilience |

| Document Type | Title | Source | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Document | Saudi Vision 2030 | Saudi Arabia (2016) [2] | Provides the national framework for heritage conservation and tourism development relevant to Tarout Island. |

| Academic Article | Urban Regeneration and the Search for Identity in Historic Cities | Boussaa (2017), Sustainability [10] | Discusses heritage-based urban regeneration in the Gulf, applicable to Tarout’s context. |

| Institutional Report | Qatif City Profile | UN-Habitat (2019) [1] | Offers detailed insights into Tarout Island’s urban and heritage challenges. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aldossary, M.J.; Alqahtany, A.M.; Alshammari, M.S. Cultural Heritage as a Catalyst for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: The Case of Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104431

Aldossary MJ, Alqahtany AM, Alshammari MS. Cultural Heritage as a Catalyst for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: The Case of Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104431

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldossary, Maryam J., Ali M. Alqahtany, and Maher S. Alshammari. 2025. "Cultural Heritage as a Catalyst for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: The Case of Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104431

APA StyleAldossary, M. J., Alqahtany, A. M., & Alshammari, M. S. (2025). Cultural Heritage as a Catalyst for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: The Case of Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 17(10), 4431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104431