Changes in the Touristic Attractiveness of Wild Forests Due to Forestry Activities? The Case of Romania’s Făgăraş Mountains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Touristic Attractiveness

2.2. Forest Attractiveness

2.3. Wilderness

2.4. Wilderness Tourism

2.5. Impacts of Forestry Activities on Wilderness Tourism

2.6. Critical Stances on Wilderness, Wilderness Tourism and Impacts of Forestry Activities on Wild Forests

3. Materials and Methods

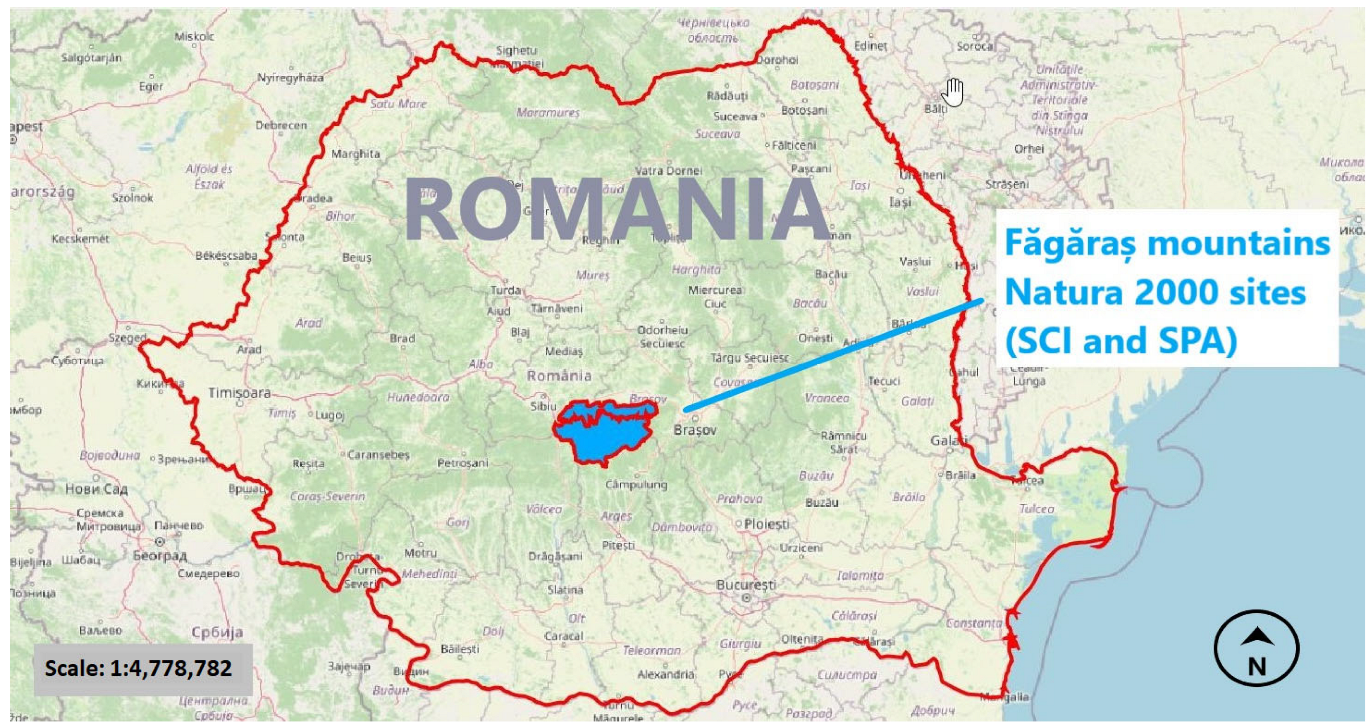

3.1. Study Site

3.2. Data Collection and Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Wilderness

4.2. Wilderness Tourism

4.3. Importance of Wilderness Tourism

4.4. Effects of Forestry Activitites on Wilderness Tourism

5. Discussion

5.1. Wilderness and Wilderness Tourism

5.2. Impacts of Forestry Activities on Touristic Attractiveness of Wild Forests

5.3. Synthesis and Evaluation of Research Question

5.4. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bachinger, M. Forest Tourism. Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Buhalis, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 332–335. [Google Scholar]

- Pröbstl, U.; Wirth, V.; Elands, B.; Bell, S. (Eds.) Introduction. In Management of Recreation and Nature Based Tourism in European Forests; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pröbstl-Haider, U.; Gugerell, K.; Maruthaveeran, S. COVID-19 and Outdoor Recreation—Lessons Learned? Introduction to the Special Issue on “Outdoor Recreation and COVID-19: Its Effects on People, Parks and Landscapes”. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 41, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šodková, M.; Purwestri, R.C.; Riedl, M.; Jarský, V.; Hájek, M. Drivers and Frequency of Forest Visits: Results of a National Survey in the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allied Market Research. Adventure Tourism Market Size, Share, Competitive Landscape and Trend Analysis Report, by Type, by Activity, by Type of Traveler, by Age Group, by Sales Channel: Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2023–2032. 2023. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/adventure-tourism-market (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Badman, T.; Bomhard, B. World Heritage and Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.; Hall, T. Wilderness Visitors, Experiences, and Management Preferences: How They Vary with Use Level and Length of Stay; Research Paper RMRS-RP-71; USDA Forest Service: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2008.

- Boivin, M.; Tanguay, G.A. Analysis of the Determinants of Urban Tourism Attractiveness: The Case of Québec City and Bordeaux. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, A.; Młynarski, W. Not Only Sale of Wood: Diversification of Sources of Revenues in Selected European Public Forest Enterprises. Folia For. Pol. 2020, 62, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeszczewik, D.; Ginter, A.; Mikusiński, G.; Pawłowska, A.; Kałuża, H.; Smithers, R.J.; Walankiewicz, W. Birdwatching, Logging and the Local Economy in the Białowieża Forest, Poland. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 2967–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupp, G.; Förster, B.; Kantelberg, V.; Markmann, T.; Naumann, J.; Honert, C.; Koch, M.; Pauleit, S. Assessing the Recreation Value of Urban Woodland Using the Ecosystem Service Approach in Two Forests in the Munich Metropolitan Region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Tourism in the Northern Wildernesses: Wilderness Discourses and the Development of Nature-Based Tourism in Northern Finland. In Nature-Based Tourism in Peripheral Areas; Hall, M., Boyd, S., Eds.; De Gruyter Brill: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.; Hall, T.; Cole, D. Naturalness, Primitiveness, Remoteness and Wilderness: Wilderness Visitors’ Understanding and Experience of Wilderness Qualities; Department of Conservation Social Sciences, University of Idaho, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute: Missoula, MT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Theoretical Approaches to Landscapes. In The Social Construction of Landscapes in Games. RaumFragen: Stadt—Region—Landschaft; Edler, D., Kühne, O., Jenal, C., Eds.; Springer VS: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ștefănică, M.; Sandu, C.B.; Butnaru, G.I.; Haller, A.-P. The Nexus between Tourism Activities and Environmental Degradation: Romanian Tourists’ Opinions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, C.; Sirén, A.; Hedblom, M.; Fredman, P. A Conceptual Framework of Indicators for the Suitability of Forests for Outdoor Recreation. Ambio 2024, 54, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, S.; Uysal, M. Destination Attractiveness Based on Supply and Demand Evaluations: An Analytical Framework. J. Travel. Res. 2006, 44, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Tverijonaite, E. Wilderness as Tourism Destination: Place Meanings and Preferences of Tourism Service Providers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. Symbolic Values: The Overlooked Values That Make Wilderness Unique. Int. J. Wilderness 2005, 11, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Novel Framework for Research and Critical Engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotašková, E. A Tour into Untouched Land: Enacting Wilderness through Relational Engagements. Ethnography 2024, 14661381241260879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. Urban Wilderness: Supply, Demand, and Access. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.; Suter, J.; McCollum, D.W. Camping in Clearcuts: The Impacts of Timber Harvesting on USFS Campground Utilization. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 44, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshaw, H.W.; Sheppard, S.R.J. Using the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum to Evaluate the Temporal Impacts of Timber Harvesting on Outdoor Recreation Settings. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2013, 1–2, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Clarke, N.; Dramstad, W.; Fjellstad, W. Effects of Bioenergy Extraction on Visual Preferences in Boreal Forests: A Review of Surveys from Finland, Sweden and Norway. Scand. J. For. Res. 2016, 31, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrică, B.; Şerban, P.-R.; Mocanu, I.; Damian, N.; Grigorescu, I.; Dumitraşcu, M.; Dumitrică, C. Developing an Indicator-Based Framework to Measure Sustainable Tourism in Romania. A territorial approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, A.-C.; Coroș, M.-M.; Pop, C. Mountain Tourism in the Perception of Romanian Tourists: A Case Study of the Rodna Mountains National Park. Information 2021, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linca, A.; Toma, E. Study regarding the evolution of mountain tourism and rural mountain tourism in Romanian Carpathians. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2021, 21, 463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Erdeli, G.; Dinca, A.I. Tourism—A Vulnerable Strength in the Protected Areas of the Romanian Carpathians. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luick, R.; Reif, A.; Schneider, E.; Grossmann, M.; Fodor, E. Virgin Forests at the Heart of Europe. The Importance, Situation and Future of Romania’s Virgin Forests; BLNN Mitteilungen des Badischen Landesvereins für Naturkunde und Naturschutz 24: Freiburg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco, M.; Ferrier, S.; Harwood, T.D.; Hoskins, A.J.; Watson, J.E.M. Wilderness Areas Halve the Extinction Risk of Terrestrial Biodiversity. Nature 2019, 573, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barredo, J.; Brailescu, C.; Teller, A.; Sabatini, F.; Mauri, A.; Janouskova, K. Mapping and Assessment of Primary and Old-Growth Forests in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/797591 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Barredo, J.I.; Rivero, I.M.; Janoušková, K. Assessing Disturbances in Surviving Primary Forests of Europe. Conserv. Biol. 2025, 39, e14404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stăncioiu, P. Biodiversity Conservation in Forest Management. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forest and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mikoláš, M.; Svoboda, M.; Pouska, V.; Morrissey, R.C.; Donato, D.C.; Keeton, W.S.; Nagel, T.A.; Popescu, V.D.; Müller, J.; Bässler, C.; et al. Comment on “Opinion Paper: Forest Management and Biodiversity”: The Role of Protected Areas Is Greater than the Sum of Its Number of Species. Web Ecol. 2014, 14, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrişor, A.-I.; Sirodoev, I.; Ianoş, I. Trends in the National and Regional Transitional Dynamics of Land Cover and Use Changes in Romania. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schickhofer, M.; Schwarz, U. Inventory of Potential Primary and Old-Growth Forest Areas in Romania (PRIMOFARO). Identifying the Largest Intact Forests in the Temperate Zone of the European Union; EuroNatur Foundation: Radolfszell, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, C.; Senf, C.; Nita, M.D.; Sabatini, F.M.; Oeser, J.; Seidl, R.; Kuemmerle, T. Using Historical Spy Satellite Photographs and Recent Remote Sensing Data to Identify High-conservation-value Forests. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 36, e13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on Nature Restoration and Amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1991/oj (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030—Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0380 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Inghams UK. The Walking Etiquette Report 2023. Available online: https://www.inghams.co.uk/walking-holidays/insider-guides/the-walking-etiquette-report-2023 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Kaltenborn, B.; Bredin, Y.; Gjershaug, J.O. Biodiversity Assessment of the Fagaras Mountains, Romania; NINA Report 1236; Norwegian Institute for Nature Research: Trondheim, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Veen, P.; Fanta, J.; Raev, I.; Biriş, I.-A.; de Smidt, J.; Maes, B. Virgin Forests in Romania and Bulgaria: Results of Two National Inventory Projects and Their Implications for Protection. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.B.; Crouch, I.C. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI Publishing: Wallingford Oxon, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, W.T.; Lee, J.M.; Ding, J.F.; Pham, C.V. Exploring Tourism Attractiveness Factors and Consumption Patterns of Southeast Asian Tourists to Taiwan. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2401147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracolici, M.F.; Nijkamp, P. The Attractiveness and Competitiveness of Tourist Destinations: A Study of Southern Italian Regions. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, E.J.; Jarvis, L.P. The Psychology of Leisure Travel. Effective Marketing and Selling of Travel Services; CBI Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Hunt, C.A.; Jia, X.; Niu, L. Evaluating Nature-Based Tourism Destination Attractiveness with a Fuzzy-AHP Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A.; Malec, M. Evaluating Local Attractiveness for Tourism and Recreation—A Case Study of the Communes in Brzeski County, Poland. Land 2021, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpak, N.; Muzychenko-Kozlovska, O.; Gvozd, M.; Sroka, W.; Havryliuk, M. Comprehensive Assessment of the Influence of Factors on the Attractiveness of a Country’s Tourism Brand—A Model Approach. J. Tour. Serv. 2022, 13, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.A. Vacationscape: Developing Tourist Areas; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fossgard, K.; Fredman, P. Dimensions in the Nature-Based Tourism Experiencescape: An Explorative Analysis. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 28, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A. Sustainability in Tourism: Impact of Attractiveness Factors in the World’s Most Visited Destinations. J. Environ. Dev. 2024, 33, 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadalipour, Z.; Imani Khoshkhoo, M.H.; Eftekhari, A.R. An Integrated Model of Destination Sustainable Competitiveness. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2019, 29, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Runnström, M. Purism Scale Approach for Wilderness Mapping in Iceland. In Mapping Wilderness: Concepts, Techniques and Applications; Carver, S., Fritz, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Botti, L.; Peypoch, N.; Solonandrasana, B. Time and Tourism Attraction. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 594–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, N. Touristic Attraction Systems. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaykh-Baygloo, R. Foreign Tourists’ Experience: The Tri-Partite Relationships among Sense of Place toward Destination City, Tourism Attractions and Tourists’ Overall Satisfaction—Evidence from Shiraz, Iran. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.F.; Huang, H.I.; Yeh, H.R. Developing an Evaluation Model for Destination Attractiveness: Sustainable Forest Recreation Tourism in Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieger, T.; Laesser, C. Attraktionspunkte: Multioptionale Erlebniswelten für wettbewerssfähige Standorte [Points of Attraction: Multi-Optional Worlds of Experience for Competitive Locations]; Verlag Paul Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tudoran, G.-M.; Cicșa, A.; Cicșa (Boroeanu), M.; Dobre, A.-C. Management of Recreational Forests in the Romanian Carpathians. Forests 2022, 13, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H.; Hallikainen, V. Effect of the Season and Forest Management on the Visual Quality of the Nature-Based Tourism Environment: A Case from Finnish Lapland. Scand. J. For. Res. 2017, 32, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, B.; Thompson, J.R.; Brunson, M.; Johnson, R. A Decade of Recreation Ratings for Six Silviculture Treatments in Western Oregon. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 75, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Stride, C.B.; Fischer, C.; Ginzler, C.; Hunziker, M. Integrating Recreation into National Forest Inventories—Results from a Forest Visitor Survey in Winter and Summer. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 39, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.E. Hikers’ Perspectives on Solitude and Wilderness. Int. J. Wilderness 2001, 7, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, R.; Lime, D. Defining and Managing the Quality of Wilderness Recreation Experiences. In Proceedings of the Wilderness Science in a Time of Change Conference: USDA Forest Service Proceedings, RMRS-P-15-Vol. 4 Wilderness Visitors, Experiences, and Visitors Management; Missoula, MT, USA, 23–27 May 1999, Cole, D., McCool, S., Borrie, W., O’Loughlin, J., Eds.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 2000; pp. 13–52. [Google Scholar]

- The Wilderness Act of 1964. US Law Pub. L. 88-577. An Act to Establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the Permanent Good of the Whole People, and for Other Purposes; 1964. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-78/pdf/STATUTE-78-Pg890.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Saarinen, J. Tourism into the Wild: The Limits of Tourism in Wilderness. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and the Environment; Holden, A., Fennel, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Arnell, A.P.; Contu, S.; De Palma, A.; Ferrier, S.; Hill, S.L.L.; Hoskins, A.J.; Lysenko, I.; Phillips, H.R.P.; et al. Has Land Use Pushed Terrestrial Biodiversity beyond the Planetary Boundary? A Global Assessment. Science 2016, 353, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, Z.; Vancura, V.; Rossberg, M.; Pflüger, G.; Schikorr, K. European Wilderness Quality Standard and Audit System Version 1.8. In Wildnis im Dialog Wege zu mehr Wildnis in Deutschland; Finck, P., Klein, M., Riecken, U., Paulsch, C., Eds.; BFN, Bundesamt für Naturschutz: Bonn, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.N.; Stankey, G.H. The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum: A Framework for Planning, Management, and Research; General Technical Report PNW-GTR-098; US Departement of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 1979. [CrossRef]

- Lesslie, R. The Wilderness Continuum Concept and Its Application in Australia: Lessons for Modern Conservation. In Mapping Wilderness; Carver, S., Fritz, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J. Wilderness Tourism. In Routledge Handbook of the Tourist Experience; Sharpley, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 521–532. [Google Scholar]

- Küchler-Krischun, J.; Walter, A. National Strategy on Biological Diversity; Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU): Berlin, Germany, 2007.

- Dunn, C. The Unappreciated Significance and Source of Meaning in Wild Landscapes: An Arctic Case. Environ. Values 2024, 33, 626–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.H.; Wolf-Watz, D. Nature to Place: Rethinking the Environmental Connectedness Perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Liang, Y.W.; Weng, S.C. Recreationist-Environment Fit and Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Wartmann, F.M.; Dubernet, I.; Fischer, C.; Hunziker, M. Urban Forest Usage and Perception of Ecosystem Services—A Comparison between Teenagers and Adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.M.; Winder, S.G.; Wood, S.A.; Miller, L.; Lia, E.H.; Cerveny, L.K.; Lange, S.; Kolstoe, S.H.; McGrady, G.; Roth, A. Where Wilderness Is Found: Evidence from 70,000 Trip Reports. People Nat. 2024, 6, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N. Wilderness Experiences What Should We Be Managing For? Int. J. Wilderness 2004, 3, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shiovitz-Ezra, S.; Rozen, R. Alone but Not Lonely: The Concept of Positive Solitude. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenhorst, S.; Jones, C. Wilderness Solitude: Beyond the Social-Spatial Perspective. In Visitor Use Density and Wilderness Experience: USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-20, Missoula, 1–3 June 2000; Freimund, W.A., Cole, D., Eds.; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 2001; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, R. Frameworks for Defining and Managing the Wilderness Experience. In Wilderness Visitor Experiences: Progress in Research and Management: USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-66, April 4–7, 2011; Missoula, MT; Cole, D., Ed.; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 2012; pp. 158–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, M.; Urry, J. The New Mobilities Paradigm. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2006, 38, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.I.C. Rethinking Embodiment in Tourism Research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2025, 110, 103892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.S.; Stone, M.T. Wilderness Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1019–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Speitz, M. Conceptualization of Wilderness. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Roggenbuck, J. Managing for Primitive Recreation in Wilderness. Int. J. Wilderness 2004, 10, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kil, N.; Stein, T.V.; Holland, S.M. Influences of Wildland–Urban Interface and Wildland Hiking Areas on Experiential Recreation Outcomes and Environmental Setting Preferences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 127, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilović, N.; Lazić, D. Forest Devastation and illegal logging—Impediment to development of tourism. In Proceedings of the Tourism International Scientific Conference—TISC, Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia, 3–5 September 2020; Volume 5, pp. 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R.J.; Duinker, P.N.; Beckley, T.M. Capturing Old-Growth Values for Use in Forest Decision-Making. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, L.M.; Boxall, P.; Englin, J.; Haider, W. Remote Tourism and Forest Management: A Spatial Hedonic Analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voda, M.; Torpan, A.; Moldovan, L. Wild Carpathia Future Development: From Illegal Deforestation to ORV Sustainable Recreation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, P.; Obrador, P.; Tucker, H. Trajectories of Embodiment in Tourist Studies. Tour. Stud. 2021, 21, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzova, D.; Sanz-Blas, S.; Cervera-Taulet, A. “Sensing” the Destination: Development of the Destination Sensescape Index. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, N.; Farrell, H. Taking a Hike: Exploring Leisure Walkers Embodied Experiences. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2018, 19, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, O. A Future for Native Forests Means Leisure, Not Logging. Nat. New South Wales 2015, 59, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, M.; Drenthen, M.; de Groot, W.T. Public Visions of the Human/Nature Relationship and Their Implications for Environmental Ethics. Environ. Ethics 2011, 33, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Pascual, U. A Typology of Elementary Forms of Human-Nature Relations: A Contribution to the Valuation Debate. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 35, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.P.; Rose, J.N. Access for Whom? White Environmentalism, Recreational Colonization, and Civic Recreation Racialization. Adm. Theory Prax. 2024, 46, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sene-Harper, A.; Mowatt, R.; Floyd, M. A People’s Future of Leisure Studies: Political Cultural Black Outdoors Experiences. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2022, 40, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Price, L.L.; Tierney, P. Communicative Staging of the Wilderness Servicescape. Serv. Ind. J. 1998, 18, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaryan, L. Nature as a Commercial Setting: The Case of Nature-Based Tourism Providers in Sweden. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1893–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management; CABI: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R.; Mas, I.M.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Blázquez-Salom, M. Tourism and Degrowth: An Emerging Agenda for Research and Praxis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1745–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiser, F.; Müller, C.; Phan, P.; Mathes, G.; Steinbauer, M.J. Europe’s Lost Landscape Sculptors: Today’s Potential Range of the Extinct Elephant Palaeoloxodon Antiquus. Front. Biogeogr. 2025, 18, e135081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, D.; Csesznek, C. The Groups of Caroling Lads from Făgăraș Land (Romania) as Niche Tourism Resource. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Tourism Highlights; UNWTO (World Tourism Organization): Madrid, Spain, 2024.

- Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2024—Romania; WTTC (World Travel & Tourism Council): London, UK, 2024.

- Puczkó, L.; Meyer, M.; Voskarova, M.; Sziva, I. Sustainable Tourism in the Carpathians. In Mountain Tourism: Experiences, Communities, Environments and Sustainable Futures; Richins, H., Hull, J., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2016; pp. 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Miu, I.V.; Rozylowicz, L.; Popescu, V.D.; Anastasiu, P. Identification of Areas of Very High Biodiversity Value to Achieve the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 Key Commitments. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicsa, A.; Comanici, R.; Cătălin, C.; Corâiu, F.; Jitaru, P.; Algasovschi, M.; Lazăr, G. Virgin Forests and Monumental Trees from Făgăras Forest District. Rev. Silvic. Cineg. 2019, 24, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Environment, Ecosystems Ltd.; Sundseth, K. The EU Birds and Habitats Directives—For Nature and People in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/49288 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Nichiforel, L.; Bouriaud, L. Changing Governance and Policies. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Vlad, R. Moving Away from a Generalized Stumpage Sales System. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D., Eds.; Transilvania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nichiforel, L. Forest Ownership and Its Challenging Role in the Forest-Based Bioeconomy. In The Plan B for Romania’s Forests and Society; Giurca, A., Dima, D., Eds.; Transilviania University Press: Brasov, Romania, 2022; pp. 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Comanescu, L.; Nedelea, A.; Dobre, R. Evaluation of Geomorphosites in Vistea Valley (Fagaras Mountains-Carpathians, Romania). Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2011, 6, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalogul Național al Pădurilor Virgine Și Cvasivirgine [National Catalogue of Virgin and Quasi-Virgin Forests Ministry of Environment, Water and Forests]; Ministerul Mediului, Apelor și Pădurilo: Bucharest, Romania, 2023; Available online: https://mmediu.ro/en/portal-gis/date-gis/paduri-virgine-si-cvasivirgine/catalogul-national-al-padurilor-virgine-si-cvasivirgine/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Knapp, H. Personal Impressions of a Forest Excursion to Romania Between Virgin Forest Wilderness, Rural Idyll and Forest Destruction. 2016. Available online: https://www.romaniacurata.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Knapp_Romania_Report_min.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Qualitative Content Analysis Methods, Practice and Software; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mayering, P. Qualitative Content Analysis; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. Generating Qualitative Data with Experts and Elites. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; pp. 652–665. [Google Scholar]

- Gizzi, M.; Rädiker, S. (Eds.) The Practice of Qualitative Data Analysis. Research Examples Using MAXQDA; MaxQDA Press: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen, V.S.; Frivold, L.H. Public Preferences for Forest Structures: A Review of Quantitative Surveys from Finland, Norway and Sweden. Urban For. Urban Green. 2008, 7, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Zollet, S. Neo-Endogenous Revitalisation: Enhancing Community Resilience through Art Tourism and Rural Entrepreneurship. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bachinger, M.; Holban, I.; Luick, R.; Schickhofer, M. Changes in the Touristic Attractiveness of Wild Forests Due to Forestry Activities? The Case of Romania’s Făgăraş Mountains. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104413

Bachinger M, Holban I, Luick R, Schickhofer M. Changes in the Touristic Attractiveness of Wild Forests Due to Forestry Activities? The Case of Romania’s Făgăraş Mountains. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104413

Chicago/Turabian StyleBachinger, Monika, Ion Holban, Rainer Luick, and Matthias Schickhofer. 2025. "Changes in the Touristic Attractiveness of Wild Forests Due to Forestry Activities? The Case of Romania’s Făgăraş Mountains" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104413

APA StyleBachinger, M., Holban, I., Luick, R., & Schickhofer, M. (2025). Changes in the Touristic Attractiveness of Wild Forests Due to Forestry Activities? The Case of Romania’s Făgăraş Mountains. Sustainability, 17(10), 4413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104413