Does Green Finance Facilitate the Upgrading of Green Export Quality? Evidence from China’s Green Loan Interest Subsidies Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

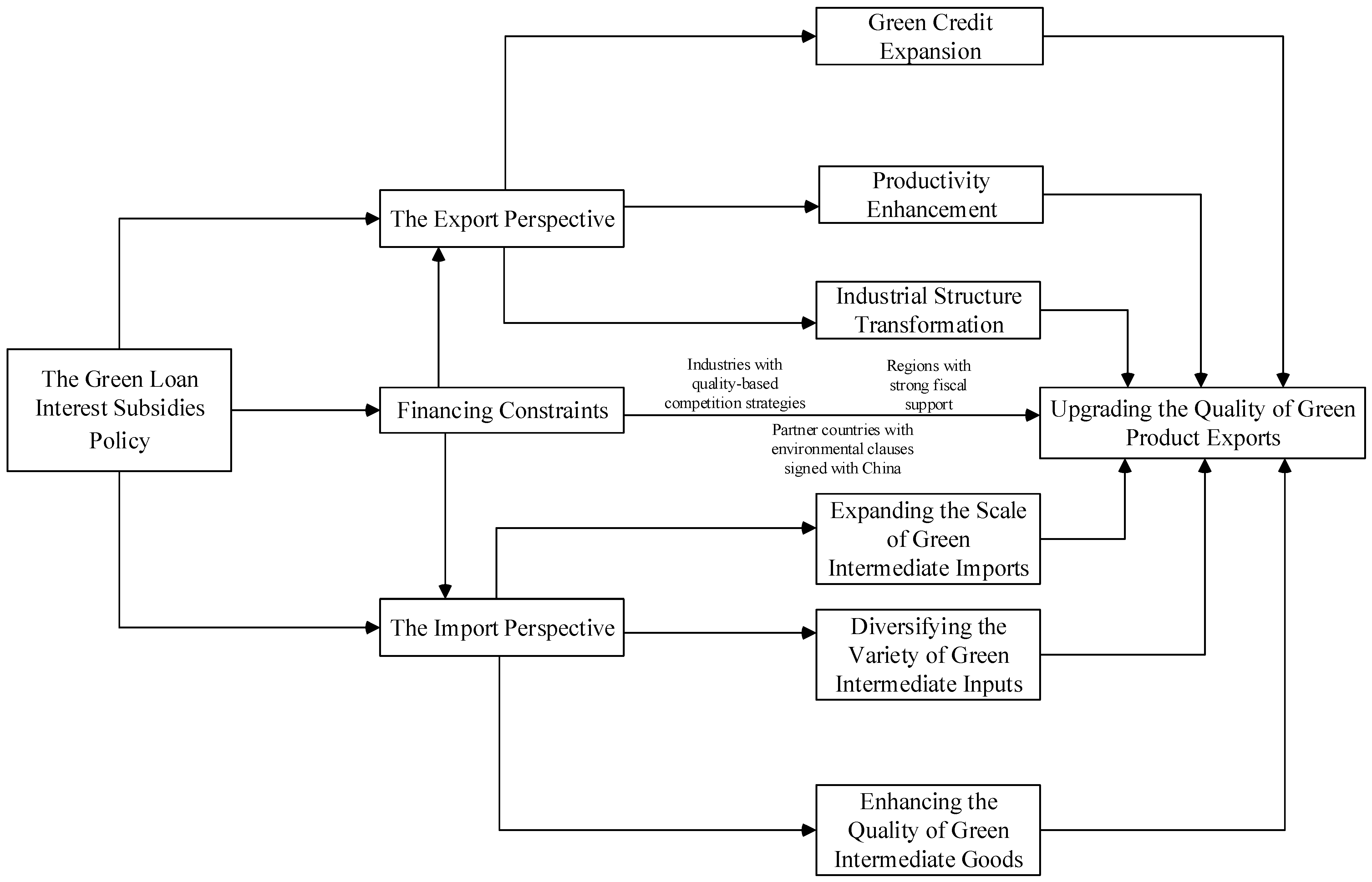

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Basic Relationship Between the Green Credit Subsidies Policy and the Export Quality of Green Products

2.2. The Green Credit Subsidies Policy and Green Product Export Quality Upgrading: Export Level

2.3. The Green Credit Subsidies Policy and Upgrading Green Product Export Quality: Import Level

2.4. Heterogeneity Analysis of Green Credit Interest Subsidy Policies

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Setting and Descriptions of the Variables

3.1.1. Explained Variables

3.1.2. Explanatory Variable

3.1.3. Control Variables

3.2. Data Description

4. Empirical Analysis

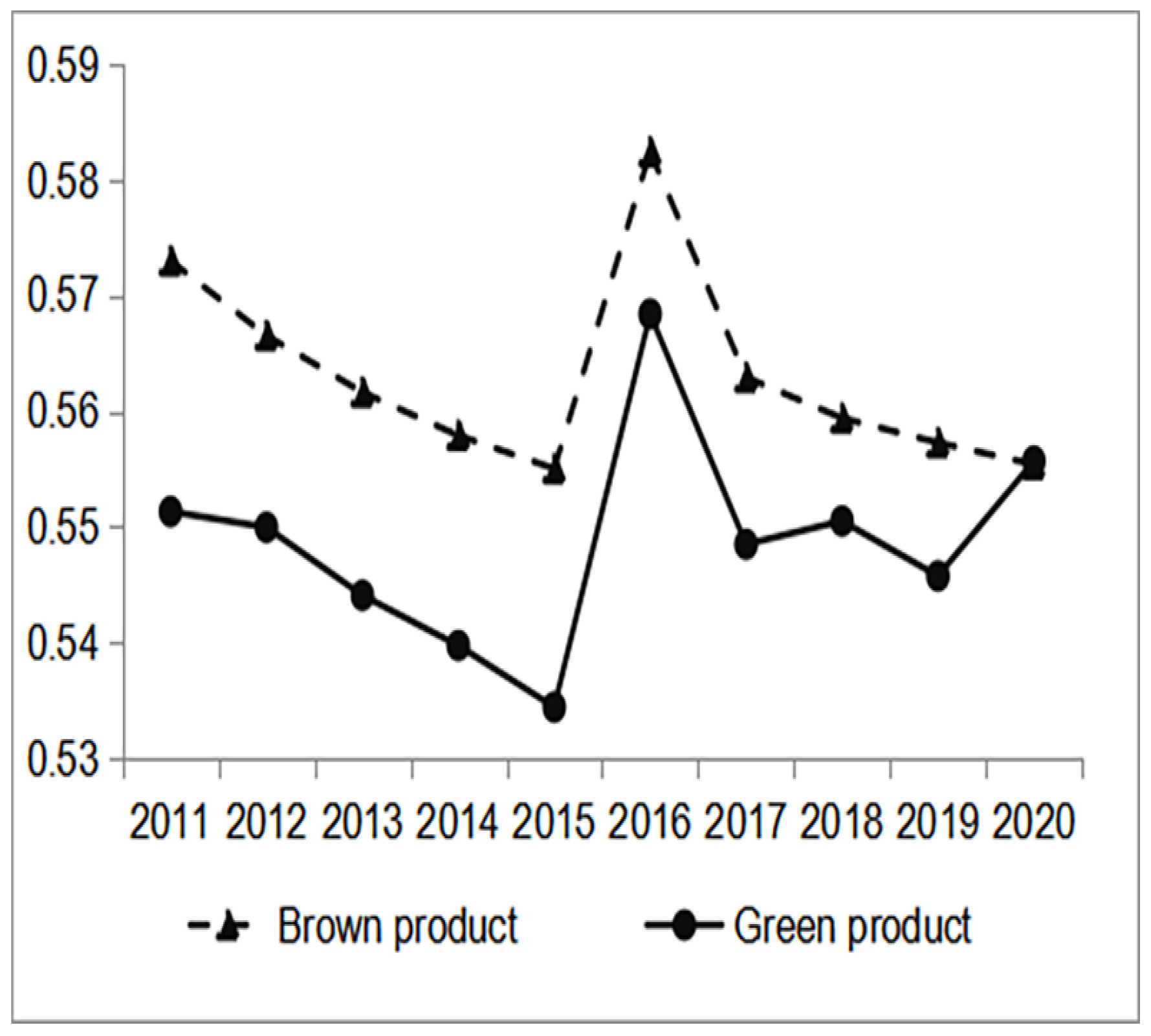

4.1. Characterization Facts Analysis

4.2. Regression to Baseline

4.3. Robustness Analyses

4.3.1. Expected Effects Test

4.3.2. Parallel Trend Testing

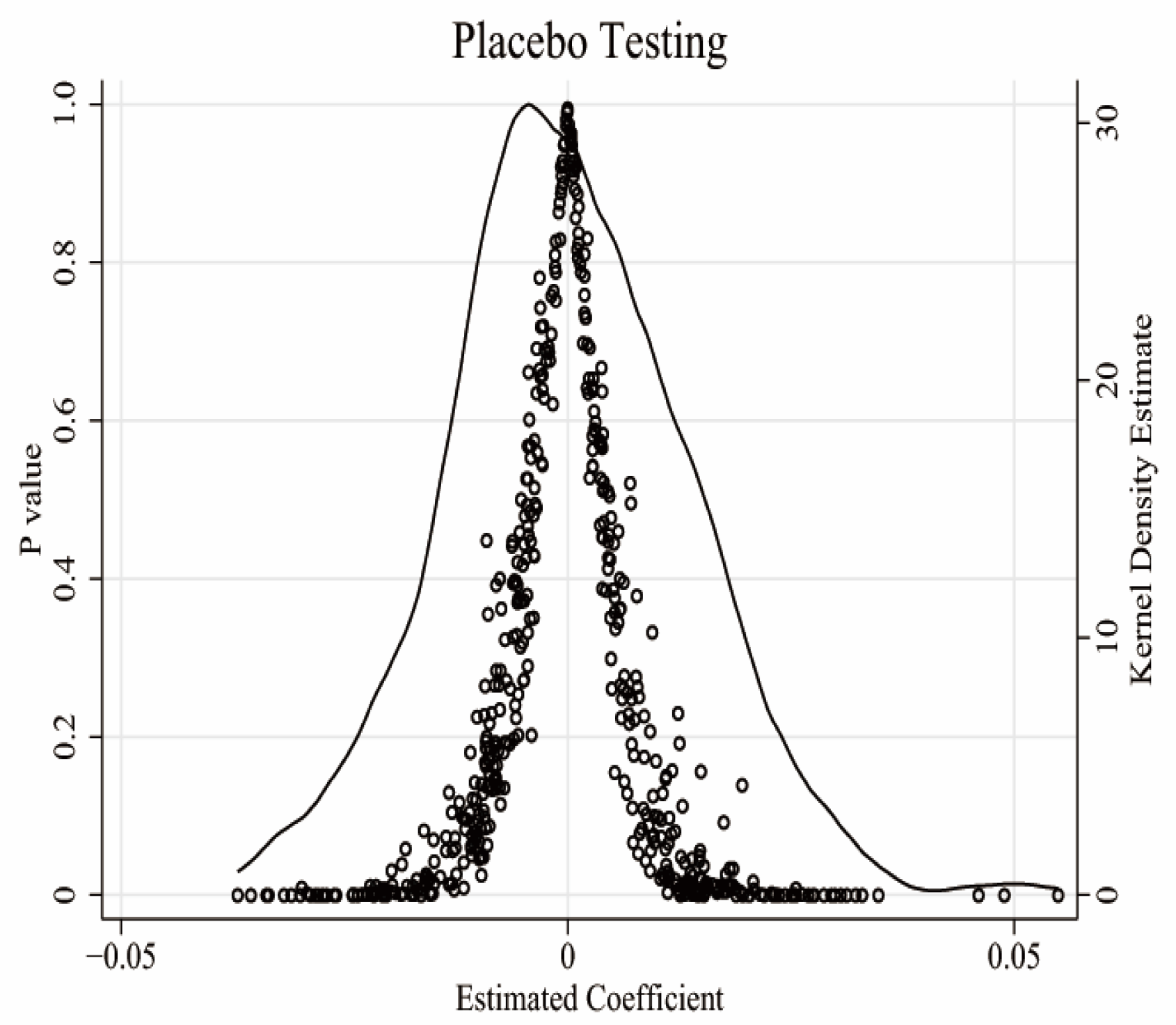

4.3.3. Placebo Testing

4.3.4. Other Robustness Tests

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

4.6. Overview of the Empirical Findings

5. Discussion

6. Research Findings and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Area | Policy Implementation Time | Name of Policy Document | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qinghai | 31 August 2016 | “General Program for the Construction of the Information Sharing System on Financial Support for Green Economic Development in Qinghai” | https://dfjrj.qinghai.gov.cn/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=33&id=2352 (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Hebei | 7 March 2017 | “The 13th Five-Year Plan for Ecological Environmental Protection in Hebei Province” | https://hbepb.hebei.gov.cn/hbhjt/zwgk/fdzdgknr/guihuazongjie/guihua/101633000446767.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Xinjiang | 1 July 2017 | “Implementing Opinions on Building a Green Financial System in the Autonomous Region” | https://www.xinjiang.gov.cn/xinjiang/gfxwj/201707/b2fc3507faa14247888e619a56b342ab.shtml (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Anhui | 23 August 2017 | “Opinions of the People’s Government of Anhui Province on Promoting Stable and Healthy Economic Development” | https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-04/17/content_5186347.htm#1 (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Beijing | 11 September 2017 | “Implementation Program on Building the Capital’s Green Financial System” | https://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcefagui/201905/t20190522_60487.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Chongqing | 7 November 2017 | “Chongqing Green Finance Development Plan (2017–2020) “ | https://www.docin.com/p-2052724305.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Hunan | 29 December 2017 | “Implementation Opinions on Promoting Green Financial Development in Hunan Province” | https://lyj.hunan.gov.cn/ztzl/lshn_77586/201712/t20171229_4913612.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Gansu | 3 January 2018 | “Opinions of the General Office of Gansu Provincial People’s Government on Building a Green Financial System” | https://www.gansu.gov.cn/gsszf/c100055/201801/100337/files/530a837943534be2b972d5a84da88ddb.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Sichuan | 18 January 2018 | “Sichuan Green All-Inclusive Development Plan” | https://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/c103046/2018/1/23/3bb4ad88ea4e47e8abc70f7afde2122e.shtml (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Hainan | 29 March 2018 | “Hainan Province Green Full Integration Reform and Development Implementation Program” | https://www.hainan.gov.cn/hainan/szfbgtwj/201804/29b3cc223a7143d888fb155f89b2385c.shtml (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Guizhou | 24 July 2018 | “Guidance on Green Finance to Facilitate Forestry Reform and Development” | https://www.sino-gf.com.cn/3007/ (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Guangxi | 25 July 2018 | “Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Finance Office and Other Departments on Building Green Financial System Implementation Opinions” | http://www.gxzf.gov.cn/zfgb/2018nzfgb_35273/d15q_35326/zzqrmzfbgtwj_35327/t1512643.shtml (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Fujian | 29 September 2018 | “Implementation Opinions on Strengthening the Linkage of Green Finance and Environmental Credit Evaluation to Boost High-Quality Development” | https://sthjj.quanzhou.gov.cn/xxgk/zfxxgkzl/zfxxgkml/fgwj/201809/t20180929_2148882.htm (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Jiangsu | 10 October 2018 | “Implementing Opinions on Further Promoting Green Financial Services and Ecological Environment for High Quality Development” | https://czt.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2018/10/10/art_51172_7836535.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Tibet | 14 November 2018 | “Tibet Autonomous Region “13th Five-Year” Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction Plan and Implementation Program” | https://www.xizang.gov.cn/zwgk/xxfb/ghjh_431/201902/t20190223_61946.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Jilin | 4 November 2019 | “Several Opinions of the General Office of the Jilin Provincial People’s Government on Promoting the Development of Green Finance” | https://xxgk.jl.gov.cn/szf/gkml/201911/t20191107_6134293.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Shanxi | 11 June 2020 | “Management Measures for the Use of Subsidized Funds for Clean Development Commissioned Loans in the Financial Sector” | https://www.shanxi.gov.cn/zfxxgk/zfxxgkzl/zc/xzgfxwj/bmgfxwj1/szfzcbm_76475/sczt_76483/202211/t20221117_7445923.shtml (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Zhejiang | 27 July 2020 | “Zhejiang Provincial Department of Economy and Information Technology on accelerating the green development of manufacturing industry guidance” | https://jxt.zj.gov.cn/art/2020/7/27/art_1582899_22232.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Shandong | 16 December 2020 | “Several measures on deepening the scientific and technological reform and attack” | http://kjt.shandong.gov.cn/art/2020/12/18/art_13361_10164730.htl (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Guangdong | 24 June 2022 | “Circular of the General Office of the People’s Government of Guangdong Province on the Issuance of the Implementation Plan for the Development of Green Finance in Guangdong Province to Support Carbon Peak Action” | https://www.gd.gov.cn/gdywdt/zwzt/kdyxtz/zcsd/content/post_4001599.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Ningxia | 1 February 2023 | “Notice of the General Office of the People’s Government of the Autonomous Region on the Issuance of the Implementation Program for the Year of Improving the Quality and Efficiency of Financial Services for the Real Economy” | https://www.nx.gov.cn/zwgk/gfxwj/202302/t20230207_3946515.html (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Liaoning | 9 June 2024 | “Liaoning Provincial Implementation Program to Promote Large-Scale Equipment Replacement and Consumer Goods Trade-In” | https://sthj.ln.gov.cn/sthj/zwdt/snyw/2024061211373772732/index.shtml (accessed on 12 March 2025) |

| Product Classification | HS2002 |

|---|---|

| Green product | 2402, 2403, 2716, 3902, 40, 41, 42, 43, 4820, 49, 62, 64, 65, 6601, 67, 73, 7411-7419, 7507, 7508, 7608–7616, 7805, 7806, 7906, 7907, 8006, 8007, 82, 83, 8401–8420, 8450, 8452, 8456–8468, 8480–8485, 8417, 8421, 8422, 8423, 8424–8449, 8451, 8453–8455, 8469, 8470, 8472, 8471, 8474–8479, 8501–8529, 8540–8543, 8573, 8530–8539, 8544–8548, 86–89, 9001–9033, 91, 92, 9401, 9402, 9403, 9404, 9405, 9406, 9506 |

| Brown product | 1006, 15, 1518, 1520, 16, 17, 18, 19, 02, 20, 21, 23, 2209, 22, 2618, 2619, 2704, 2706–2715, 28, 29, 30, 31–38, 3901, 4002, 04, 44, 4503, 4504, 46, 47, 48, 50, 51, 52, 54, 55, 53, 56, 57, 58, 59, 68, 69, 70, 710, 711, 712, 72, 7401–7410, 7501–7506, 7601–7607, 7801–7804, 7901–7905, 8001–8005, 811, 812, 814, 902, 910, 9003, 9004 |

| Variable Names | Variable Symbols | Variable Definitions | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression to baseline | Product quality of manufacturing exports | Logarithmic value of product quality plus 0.0001 for standardized manufacturing exports | 18,520,289 | −0.6984 | 0.6510 | −9.2103 | 0.0001 | |

| Policy implementation variable | Interaction term between the green loan interest subsidies policy implementation variables and product grouping variables | 18,520,849 | 0.1146 | 0.3185 | 0 | 1 | ||

| GDP at the regional level | Logarithmic value of GDP by region | 18,520,849 | 10.3928 | 0.7206 | 6.4159 | 11.6187 | ||

| Regional openness to the outside world | Logarithmic value of the ratio of total exports and imports to regional GDP by region | 18,520,849 | −1.1130 | 0.8483 | −2.8739 | 0.4042 | ||

| Level of regional FDI | Logarithmic value of total FDI by region | 18,520,849 | 9.5739 | 1.2729 | 5.9793 | 11.9153 | ||

| Regional level of e-commerce | Logarithmic value of e-commerce level in each region constructed by entropy weight method | 18,489,373 | −1.3194 | 0.7700 | −3.4567 | −0.2044 | ||

| Regional level of green innovation | Green Innovation Efficiency across Regions as Measured by the Undesired Output Super-Efficiency SBM Model | 18,520,849 | 0.6601 | 0.4514 | 0.0490 | 1.8238 | ||

| GDP at the national level | Logarithmic value of GDP per destination country | 17,971,217 | 9.4826 | 1.9593 | 0.8519 | 14.2414 | ||

| Level of openness to the outside world at the national level | Logarithm of the ratio of total exports and imports of each destination country to the gross domestic product of each destination country | 17,970,979 | −0.5771 | 0.5963 | −1.7100 | 1.0164 | ||

| Country distance | Logarithm of geographical distance from region to destination country weighted by regional export value | 18,476,683 | 3.5074 | 1.5629 | −0.9737 | 7.1593 | ||

| Free trade agreement | Free Trade Agreement with China dummy variable | 18,499,196 | 0.2511 | 0.4336 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Exchange rate fluctuations | Exchange rates expressed in RMB, indirect method of valuation | 17,955,372 | 1.1585 | 2.9754 | −2.9109 | 8.2752 | ||

| Robustness analyses | Product quality of manufacturing exports (geographic distance instrumental variable) | Logarithmic value of standardized manufacturing export product quality plus 0.0001 (geographic distance instrumental variable) | 18,520,287 | −0.7620 | 0.8596 | −6.9078 | 0.0010 | |

| Products’ green barriers to trade | Logarithmic value of the number of foreign notifications of product-level technical barriers to trade plus one. | 18,520,849 | 0.2684 | 0.4705 | 0 | 3.5323 | ||

| Export tariffs on products | Logarithmic value of export tariffs on products | 18,520,849 | 2.1426 | 0.7432 | 0 | 4.1897 | ||

| Product export tax rebate rate | Product export tax rebate rate | 18,520,849 | 0.0094 | 0.0344 | 0 | 0.1976 | ||

| Government environmental governance | The frequency of occurrence of environment-related words in regional government work reports in China and multiplied by 100. | 18,520,849 | 0.9574 | 0.2568 | 0.3670 | 1.6761 | ||

| Mechanism analysis | Scale of green credit | The inverse of the ratio of interest payments in energy-intensive industries to total interest payments in industrial industries in each region. | 18,520,849 | 0.1966 | 0.3346 | 0.0002 | 1.8757 | |

| Total factor productivity | Logarithmic value of the DEA-Malmquist productivity index | 18,489,373 | 0.0535 | 0.0235 | −0.2735 | 0.1155 | ||

| Upgrading of industrial structure | Ratio of tertiary sector to GDP by region | 18,520,849 | 0.0461 | 0.0837 | 0 | 0.4882 | ||

| Scale of imports of green intermediates | Logarithmic value of import value of green intermediates by region | 16,707,235 | 20.6418 | 2.8888 | 2.9957 | 25.3426 | ||

| Types of green intermediates imported | Logarithmic value of import types of green intermediates by region | 16,707,235 | 4.2552 | 1.3442 | 0 | 6.6425 | ||

| Green intermediate import quality | Logarithmic value of import quality of green intermediates plus 0.0001 for each region | 16,707,070 | −7.8733 | 1.0864 | −9.2103 | −4.5897 |

References

- Wang, S.; Tang, Y.; Du, Z.; Song, M. Export trade, embodied carbon emissions, and environmental pollution: An empirical analysis of China’s high-and new-technology industries. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiglio, E. Beyond carbon pricing: The role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikau, S.; Volz, U. Central Banking, Climate Change and Green Finance; Working Paper 867; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Riaz, H.; Ahmed, M.; Saeed, A. Does green finance really deliver what is expected? An empirical perspective. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordo, M.D.; Rousseau, P.L. Historical evidence on the finance-trade-growth nexus. J. Bank. Financ. 2012, 36, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y. How green finance affects export production quality: Fresh evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2024, 131, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Chen, F.; Zhang, K. The policy effect of green finance in promoting industrial transformation and upgrading efficiency in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 47474–47491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Yoshino, N. Sustainable solutions for green financing and investment in renewable energy projects. Energies 2020, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Li, X.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, B. Exploring the impact of green credit policy on green transformation of heavy polluting industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Abbassi, W.; Hunjra, A.I.; Zhang, H. How do government R&D subsidies affect corporate green innovation choices? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 93, 1378–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.; Lai, E.L.C.; Li, Y.A. Credit constraints, quality, and export prices: Theory and evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2015, 43, 390–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Cincera, M. Determinants of financing constraints. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konte, M.; Ndubuisi, G. Financial constraint, trust, and export performances: Firm-level evidence from Africa. J. Inst. Econ. 2021, 17, 583–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D.C. Do credit constraints favor dirty production? Theory and plant-level evidence. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 84, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhgaliyeva, D.; Kapsaplyamova, Z.; Low, L. Implications of Fiscal and Financial Policies for Unlocking Green Finance and Green Investment; Working Paper 865; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Manova, K.; Yu, Z. Multi-product firms and product quality. J. Int. Econ. 2017, 109, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, H. An evolutionary analysis of green finance sustainability based on multi-agent game. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 121799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, X.; Mo, L. The impact of green finance on export technology complexity: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qi, S.; Li, Y. Can the green finance improve export green-sophistication? New insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 82927–82937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tian, T. Blockchain-enabled enterprise bleaching green regulation banking evolution game analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 27457–27483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liao, G.; Li, Z. Loaning scale and government subsidy for promoting green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Loayza, N. Finance and the sources of growth. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 261–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Research on the impact of green finance on the upgrading of China’s regional industrial structure. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, M.; Strauss-Kahn, V. Input-trade liberalization, export prices and quality upgrading. J. Int. Econ. 2015, 95, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, M.; Berthou, A. The decision to import capital goods in India: Firms’ financial factors matter. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2012, 26, 486–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-H.; Dang, T.-T.; Nguyen, K.-A.; Pham, H.-A. Spherical fuzzy WASPAS-based entropy objective weighting for international payment method selection. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 2055–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Mao, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wan, X. The impact of intermediate product imports on industrial pollution emissions. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, E.; Fusacchia, I. Navigating the complexity: The sustainability challenges in global value chains. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2024, 16, 349–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous technological change. J. Polit. Econ. 1990, 98 Pt 2, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Siddik, A.B.; Zheng, G.-W.; Masukujjaman, M.; Bekhzod, S. The effect of green banking practices on banks’ environmental performance and green financing. Energies 2022, 15, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C.; Iacovone, L.; Javorcik, B.; Neary, J.P. Multi-product firms at home and away: Cost-versus quality-based competence. J. Int. Econ. 2015, 95, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhong, T.; Xie, Q.; Liu, H. Foreign demand, competition strategy, and export markups: Evidence from Chinese multi-product exporters. China World Econ. 2022, 30, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Tu, Y.; Zhou, P. Technical barriers to trade and export performance: Comparing exiting and staying firms. Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, H. The adoption of international standards and export behavior of multi-product firms: A perspective based on differentiated competitive strategies. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 86, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.M. Public goods in theory and practice: A note on the Minasian-Samuelson discussion. J. Law Econ. 1967, 10, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.E.; Lai, P.W.; Han, Z.Q.; Tang, Z.P. Do government policies drive institutional preferences on green investment? Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 8297–8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; He, J.; Qiao, L. Does environmental regulation affect the export competitiveness of Chinese firms? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasehinde-Williams, G.; Folorunsho, A. Environmental policy, green trade and sustainable development in Europe: New perspective on the Porter hypothesis. Energy Environ. 2023, 0958305X231193870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Oates, W.E.; Portney, P.R. Tightening environmental standards: The benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, D.; Krueger, A.B. Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 84, 772–793. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, A. The long and short (of) quality ladders. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2010, 77, 1450–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Whiting, S.H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T. Changing property-rights regimes: A study of rural land tenure in China. China Q. 2017, 232, 1026–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.E. A theoretical foundation for the gravity equation. Am. Econ. Rev. 1979, 69, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, S.; Sun, S. Foreign direct investment and export quality upgrading in China’s manufacturing sector. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2018, 54, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.W. The impact of green innovation on export quality. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 30, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, J.; Cao, R.; Wu, J.; Liu, J. How e-commerce can boost China’s high-quality agricultural exports. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1372129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Y. The impact of regional trade agreements on the quality of export products in China’s manufacturing industry. J. Asian Econ. 2022, 80, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Sun, C. Exchange rate fluctuations and the quality of products imported by Chinese manufacturing firms. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 2751–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Bacon, A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chaisemartin, C.; d’Haultfoeuille, X. Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2964–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kahn, M.E.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. The consequences of spatially differentiated water pollution regulation in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 88, 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Huang, C.; Liao, L. Trade liberalization and energy efficiency: Quasi-natural experiment evidence from the pilot free trade zones in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cheng, S.; Gao, Q.; Li, B. How dual value chain embedding affects energy efficiency in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 967470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Robust Standard Error | Region and Industry Bidirectional Clustering Robust Criterion Error | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality |

| did | 0.1024 *** | 0.0958 *** | 0.0964 *** | 0.1024 *** | 0.0958 *** | 0.0964 *** |

| (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0069) | (0.0064) | (0.0064) | |

| lngdp_proid | 0.1280 *** | 0.1200 *** | 0.1280 *** | 0.1200 *** | ||

| (0.0040) | (0.0041) | (0.0432) | (0.0433) | |||

| lnopen_proid | 0.0403 *** | 0.0391 *** | 0.0403 *** | 0.0391 *** | ||

| (0.0013) | (0.0014) | (0.0100) | (0.0100) | |||

| lnfdi | 0.0218 *** | 0.0217 *** | 0.0218 *** | 0.0217 *** | ||

| (0.0007) | (0.0007) | (0.0057) | (0.0057) | |||

| lnEC | 0.0364 *** | 0.0358 *** | 0.0364 *** | 0.0358 *** | ||

| (0.0014) | (0.0014) | (0.0085) | (0.0086) | |||

| green_innovation | 0.0070 *** | 0.0069 *** | 0.0070 | 0.0069 | ||

| (0.0008) | (0.0008) | (0.0061) | (0.0062) | |||

| lngdp_country | 0.0355 *** | 0.0355 *** | ||||

| (0.0011) | (0.0038) | |||||

| lnopen_country | 0.0218 *** | 0.0218 *** | ||||

| (0.0009) | (0.0022) | |||||

| lndis | −0.0077 *** | −0.0077 * | ||||

| (0.0007) | (0.0039) | |||||

| RTA | 0.0091 *** | 0.0091 *** | ||||

| (0.0015) | (0.0020) | |||||

| lnrate | −0.0115 *** | −0.0115 *** | ||||

| (0.0005) | (0.0011) | |||||

| year/product/industry/province/country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year-product fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| province-product-country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −0.7101 *** | −2.1609 *** | −2.3665 *** | −0.7101 *** | −2.1609 *** | −2.3665 *** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0420) | (0.0437) | (0.0008) | (0.4390) | (0.4346) | |

| Observations | 18,520,289 | 18,488,823 | 17,767,879 | 18,520,289 | 18,488,823 | 17,767,879 |

| R-squared | 0.648 | 0.648 | 0.648 | 0.648 | 0.648 | 0.648 |

| Expected Effects | Quality Recalculation | Re-Identification Processing Group | Balance Panel | Omitted Variables | Psm_did | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Variables | lnquality | lnquality_d | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality |

| did_pre | 0.0207 | ||||||

| (0.0140) | |||||||

| did | 0.0815 *** | 0.0186 ** | 0.0663 *** | 0.0971 *** | 0.1014 *** | 0.1186 *** | |

| (0.0111) | (0.0092) | (0.0013) | (0.0063) | (0.0059) | (0.0153) | ||

| dids | 0.0578 *** | ||||||

| (0.0086) | |||||||

| lnbarriers | 0.0225 *** | ||||||

| (0.0046) | |||||||

| lnduty | −0.0118 *** | ||||||

| (0.0021) | |||||||

| Tax | −0.0420 | ||||||

| (0.0280) | |||||||

| gov | −0.0326 *** | ||||||

| (0.0049) | |||||||

| control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year/product/industry/province/country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year-product fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| province-product-country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −2.3227 | −0.7641 *** | −2.8867 *** | −1.8192 *** | −2.3326 *** | −2.5013 *** | −1.5942 *** |

| (1.3725) | (0.0011) | (0.4568) | (0.0948) | (0.4333) | (0.4362) | (0.3385) | |

| Observations | 17,767,879 | 18,520,287 | 17,767,879 | 5,211,339 | 17,767,879 | 17,767,879 | 3,161,643 |

| R-squared | 0.648 | 0.653 | 0.647 | 0.582 | 0.648 | 0.648 | 0.804 |

| Year | lnquality_Green_Product | lnquality_Brown_Product | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moran’s I | Z | Moran’s I | Z | |

| 2011 | 0.094 | 3.667 | 0.106 | 4.041 |

| 2012 | 0.086 | 3.434 | 0.113 | 4.200 |

| 2013 | 0.070 | 3.008 | 0.101 | 3.852 |

| 2014 | 0.054 | 2.575 | 0.074 | 3.300 |

| 2015 | 0.047 | 2.339 | 0.058 | 2.778 |

| 2016 | 0.072 | 3.121 | 0.083 | 3.576 |

| 2017 | 0.103 | 3.997 | 0.110 | 4.312 |

| 2018 | 0.119 | 4.566 | 0.120 | 4.584 |

| 2019 | 0.109 | 4.283 | 0.118 | 4.553 |

| 2020 | 0.148 | 5.306 | 0.124 | 4.839 |

| Variables | lnquality_Green_Product | lnquality_Brown_Product |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| ρ | 0.4108 *** | 0.4699 *** |

| (0.1436) | (0.1317) | |

| policy | 0.1207 ** | 0.0842 *** |

| (0.0504) | (0.0317) | |

| W × policy | 0.7960 ** | 0.5831 ** |

| (0.3582) | (0.2294) | |

| control variables | Y | Y |

| year/province | Y | Y |

| fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Direct Effect | 0.1534 ** | 0.1135 ** |

| (0.0627) | (0.0442) | |

| Indirect Effect | 1.5745 * | 1.2942 * |

| (0.9014) | (0.7712) | |

| Total Effect | 1.7279 * | 1.4076 * |

| (0.0859) | (0.8049) | |

| N | 310 | 310 |

| R-squared | 0.4497 | 0.2155 |

| Cost Competition Strategy | Quality Competition Strategy | Weak Policy Coordination Group | Strong Policy Coherence Group | Countries That Do Not Have Environmental Protection Clauses with China | Countries with Which China Has Signed Environmental Protection Clauses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality |

| did | 0.0970 *** | 0.2204 ** | 0.0808 *** | 0.0987 *** | 0.0899 *** | 0.1230 *** |

| (0.0064) | (0.0834) | (0.0196) | (0.0062) | (0.0059) | (0.0092) | |

| control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year/product/industry/province/country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year-product fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| province-product-country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| χ2 | 28.53 | 136.14 | 163.17 | |||

| p-value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||

| Constant | −2.3969 *** | −1.5622 *** | −2.9735 *** | −0.7436 | −2.3206 *** | −2.4808 *** |

| (0.4489) | (0.4969) | (0.4970) | (0.4875) | (0.4003) | (0.5880) | |

| Observations | 16,983,616 | 784,263 | 4,139,488 | 13,628,391 | 14,305,659 | 3,462,220 |

| R-squared | 0.647 | 0.682 | 0.694 | 0.649 | 0.655 | 0.639 |

| Scale of Green Credit | Total Factor Productivity | Upgrading of Industrial Structure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Variables | Green_credit | lnquality | lnquality | lntfp | lnquality | lnquality | ISUP | lnquality | lnquality |

| did | 0.0176 *** | 0.0938 *** | 0.0024 * | 0.0960 *** | 0.0046 ** | 0.0939 *** | |||

| (0.0064) | (0.0064) | (0.0013) | (0.0063) | (0.0023) | (0.0065) | ||||

| Green_credit | 0.1510 *** | 0.1453 *** | |||||||

| (0.0057) | (0.0063) | ||||||||

| lntfp | 0.1989 *** | 0.1627 *** | |||||||

| (0.0559) | (0.0563) | ||||||||

| ISUP | 0.5587 *** | 0.5369 *** | |||||||

| (0.0230) | (0.0273) | ||||||||

| control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year/product/industry/province/country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year-product fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| province-product-country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −0.2898 | −3.3150 *** | −2.3244 *** | −0.0313 | −3.3757 *** | −2.3614 *** | 0.0732 | −3.4006 *** | −2.4058 *** |

| (0.3052) | (0.4690) | (0.4249) | (0.0433) | (0.4723) | (0.4297) | (0.0830) | (0.4633) | (0.4224) | |

| Observations | 17,768,383 | 17,767,879 | 17,767,879 | 17,768,383 | 17,767,879 | 17,767,879 | 17,768,383 | 17,767,879 | 17,767,879 |

| R-squared | 0.922 | 0.647 | 0.648 | 0.665 | 0.647 | 0.648 | 0.915 | 0.647 | 0.648 |

| Sobel |Z| | 2.735 | 2.185 | 2.025 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.0062 | 0.0289 | 0.0429 | ||||||

| Bootstrap (50 times) confidence intervals | [0.0025, 0.0026] | [0.0004, 0.0005] | [0.0021, 0.0022] | ||||||

| Scale of Imports of Green Intermediates | Types of Green Intermediates Imported | Green Intermediate Import Quality | |||||||

| (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | |

| Variables | lnvalue_bec | lnquality | lnquality | lnsize_bec | lnquality | lnquality | lnquality_bec | lnquality | lnquality |

| did | 0.0147 *** | 0.0966 *** | 0.1230 *** | 0.0982 *** | 0.0234 *** | 0.0967 *** | |||

| (0.0037) | (0.0067) | (0.0275) | (0.0069) | (0.0027) | (0.0068) | ||||

| lnvalue_bec | 0.2451 *** | 0.2048 *** | |||||||

| (0.0292) | (0.0262) | ||||||||

| lnsize_bec | 0.0280 *** | 0.0114 * | |||||||

| (0.0072) | (0.0061) | ||||||||

| lnquality_bec | 0.2734 *** | 0.1264 *** | |||||||

| (0.0459) | (0.0341) | ||||||||

| control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year/product/industry/province/country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| year-product fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| province-product-country fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | 5.4969 *** | −4.8684 *** | −3.5204 *** | 25.1027 *** | −4.2261 *** | −2.6797 *** | 1.4218 *** | −3.8768 *** | −2.5744 *** |

| (0.2489) | (0.4975) | (0.4599) | (1.1211) | (0.5339) | (0.4948) | (0.1713) | (0.4972) | (0.4716) | |

| Observations | 16,189,964 | 16,189,515 | 16,189,515 | 16,189,964 | 16,189,515 | 16,189,515 | 16,189,964 | 16,189,515 | 16,189,515 |

| R-squared | 0.981 | 0.644 | 0.645 | 0.992 | 0.644 | 0.645 | 0.918 | 0.644 | 0.645 |

| Sobel |Z| | 3.554 | 1.710 | 3.416 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.0004 | 0.0873 | 0.0006 | ||||||

| Bootstrap (50 times) confidence intervals | [0.0009, 0.0012] | [0.0007, 0.0008] | [0.0045, 0.0048] | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X. Does Green Finance Facilitate the Upgrading of Green Export Quality? Evidence from China’s Green Loan Interest Subsidies Policy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104375

Shi J, Li J, Jiang S, Liu Y, Yin X. Does Green Finance Facilitate the Upgrading of Green Export Quality? Evidence from China’s Green Loan Interest Subsidies Policy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104375

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Jinming, Jia Li, Shuai Jiang, Yingqian Liu, and Xiaoyu Yin. 2025. "Does Green Finance Facilitate the Upgrading of Green Export Quality? Evidence from China’s Green Loan Interest Subsidies Policy" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104375

APA StyleShi, J., Li, J., Jiang, S., Liu, Y., & Yin, X. (2025). Does Green Finance Facilitate the Upgrading of Green Export Quality? Evidence from China’s Green Loan Interest Subsidies Policy. Sustainability, 17(10), 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104375