1. Introduction

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are pivotal for shaping societal norms and addressing global challenges, thereby extending their influence beyond the traditional realms of education and research [

1]. These institutions are increasingly being acknowledged for the significant role they play in societal development and emphasizing the concept of university social responsibility (USR). This expanded role necessitates that HEIs not only impart education and conduct related research, but also actively engage in addressing societal issues by incorporating ethical, social, and environmental considerations into their core operations. These evolving societal expectations demand that HEIs not only respond to but also proactively address and also play a leading role when tackling both global and local challenges, thereby embodying the essence of USR. Moreover, as the key component of USR is the commitment to sustainability—encompassing environmental, social, and economic dimensions—this study emphasizes how HEIs can use social media in promoting and educating others about sustainability practices among their communities, even beyond crises situations.

The importance of USR is both recognized and supported by a range of stakeholders, including accreditation and ranking agencies, national and international accreditation institutions, and students. All are increasingly aware of and demand engagement in these activities [

1,

2,

3]. Further still, changes in society, the economy, and the very structure of universities themselves have spurred these institutions to adopt a more proactive role in promoting equality, educational adequacy, and engagement in societal discourse, thereby fulfilling what is often referred to as their ‘third mission’ [

4,

5]. This mission goes beyond traditional teaching and research to include impactful societal engagement and emphasizes the need for universities to not only integrate these activities into their academic agendas, but also to actively influence and participate in societal development. Social responsibility in higher education encompasses a broad spectrum of activities that include educational outreach, community support, research for societal benefit, and active policy advocacy, thereby reflecting a clear and comprehensive approach to fulfilling their societal roles.

In this context, the COVID-19 pandemic emerges as a critical and important case study that illustrates how HEIs navigate their responsibilities during crises [

6,

7,

8]. The COVID-19 pandemic thus offers a valuable case study for examining HEIs’ social media strategies and USR due to its unique dynamics, including the sudden shift to online learning, the necessity of having real-time public health updates, and the necessary role of social media in sustaining community engagement during lockdowns. This study not only investigates the immediate responses of HEIs to the COVID-19 pandemic but also explores how these strategic communications can be extended to inform broader theoretical and practical applications in crisis communication, emphasizing the pivotal role of social media in shaping public discourse and stakeholder engagement during global crises. This particular global health emergency clearly impacted numerous facets of university life, influencing how institutions ensure student welfare, continue their educational offerings, support community initiatives, and uphold ethical standards amidst unprecedented circumstances. The pandemic indeed serves as a stark example of the HEIs’ capacity to fulfill their social responsibilities during challenging times, clearly highlighting their commitment to the well-being of society as well as their own resilience.

Within this broad spectrum of responsibilities, effective communication plays a critical role in crisis management by facilitating rapid information dissemination, stakeholder engagement, and real-time support. Thus, utilization of social media by HEIs became increasingly important for this scenario [

9,

10]. As social media platforms become ever more integral to daily communication, they can provide HEIs with essential tools to convey their USR initiatives, engage with diverse stakeholders, and build a strong sense of community and shared purpose. Through this use of social media, universities can transcend traditional communication barriers and foster dialogue, participatory engagement, and a reinforced overall commitment to societal and environmental well-being. Social media thus enhances crisis management efforts by enabling HEIs not only to disseminate crucial information swiftly but also better manage community anxiety and perceptions during turbulent times.

Building on the theory of crisis communication [

11,

12], this study investigated the extent to which HEIs use social media to communicate during a crisis and scrutinized how their communications aligned with broader USR principles. The COVID-19 pandemic thus offered a unique opportunity to investigate these communication strategies. The goal of this study, therefore, was to contribute to the body of knowledge on how HEIs can navigate and lead in times of societal upheaval.

By analyzing the communication strategies implemented during an unprecedented global health crisis, this study provides useful insights that can guide HEIs in effectively leveraging social media for all crisis management and stakeholder engagement, thereby contributing to more resilient educational communities overall.

To this end, this study posed an important question.

That central research question sought to uncover the strategic use of social media as a critical tool in the broader social responsibility initiatives of HEIs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This question is supported by a sub-question for the quantitative part of the study, which is as follows:

And also, a sub-question for the qualitative part of the study, which is as follows:

This study used a Thick Big Data approach [

13] to analyze the posts being shared on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram using HEIs’ official profiles. It specifically utilizes various social media (SM) platforms, because, as argued by Liu et al., (2015) [

14], there is no single social media platform preferred for disseminating information during times of crisis; thus, each offers different opportunities for effective communication. This proposed method provides useful and clear insights into the rhetorical strategies HEIs use to communicate with their stakeholders [

15,

16,

17] using both quantitative and qualitative perspectives.

This study thus makes both theoretical and empirical contributions. First, it provides new insights on the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in the higher education sector by building on studies concerning the use of SM in the higher education sector [

18,

19,

20,

21]. However, only a few publications have specifically focused on the usage of SM by HEIs as a tool to communicate with stakeholders during a crisis [

18,

22,

23], Moreover, none of these studies adopted a mix of qualitative and quantitative approaches. For example, Coelho and Figueira (2021) [

22] explored how the pandemic influenced the content strategies of HEIs by analyzing Twitter posts and employing machine learning and topic modeling techniques to trace shifts in content themes during the pandemic. They revealed how HEIs adjusted their communications. Sörensen et al. (2023) [

23] conducted a comparative analysis of Swiss universities on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook and found that during COVID-19, HEI communication was mostly self-referential. Conversely, O’Shea et al.’s (2022) [

8] research was based on the qualitative approach of document analysis. Their research provided a comprehensive analysis of how HEIs across three countries managed their communication during the initial six months of the pandemic. These studies collectively underscore the adaptive strategies of HEIs during the pandemic, emphasizing the role of social media in reshaping communication approaches to address the unprecedented challenges posed by COVID-19. Considering the strategic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, this study provides a template for HEIs and other organizations to leverage social media in promoting not only immediate crisis management but also long-term community resilience and engagement. By integrating these different insights, the current study was able to build a more nuanced understanding of the strategic communication responses of HEIs during crises, particularly for leveraging social media to engage with and support their communities more effectively.

Secondly, the empirical evidence is based on using a novel method called Thick Big Data [

13], which offers benefits from using both a quantitative approach and a qualitative contextual analysis. Previous researchers who studied the use of SM in HEIs often based their research on quantitative approaches [

22,

23], frequently relying on questionnaires about social media rather than the social media data themselves [

20,

24]. The current paper, however, takes the next step and not only analyzes the social media data, but also introduces an additional netnographic approach that allows for deeper insight into how HEIs communicate with stakeholders using social media.

Finally, the empirical basis of this study provides unique insights into the development of crisis communication using SM, a focus that has rarely been investigated in Central and Eastern European (CEE) regions. The studies thus far have only focused on Anglo-Saxon countries [

8,

25,

26]; thus, there is a dearth of research on this concept and its use in other countries, including the CEE region.

Further still, this study extends the discourse on sustainability in higher education by emphasizing how HEIs can leverage social media to communicate their sustainability initiatives during crises. This study thus answers the call for further research on the marketing of higher education, especially during crises, as voiced by Manzoor et al. (2021) [

27]. It considers COVID-19 as a possible critical juncture for the development of better communication with HEIs stakeholders for enhanced participation and dialogue. In particular, this study explores how HEIs can utilize social media not only to navigate crises, but also to promote sustainable practices and foster a culture of sustainability among their stakeholders. The information presented in this article can thus contribute to the entire body of marketing knowledge and research in the context of higher education. This study also investigates the changes in HEI marketing during a crisis and especially COVID-19. The findings can therefore assist marketing specialists in understanding the different communication strategies available on social media for HEIs to use.

Additionally, this study’s insights into the social media communication strategies used during crises can guide HEIs in the future to promote sustainability and engage stakeholders in their sustainability missions more effectively.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 offers a literature review and discusses the overall theoretical framework.

Section 3 explains the methodology.

Section 4 presents the sample and its descriptive statistics, and discusses the results obtained.

Section 5 further discusses these results and concludes the study with final comments.

3. Methodology

The analytical framework of this research extends to examining how HEIs communicate their commitment to sustainability and social responsibility during crises. This process involves identifying posts that not only address the immediate crisis, but also incorporate messages that are related to environmental stewardship, community engagement, and ethical governance. This study thus analyzed the data published by Polish HEIs on their official social media accounts, from March 2020 to March 2021.

The study also examined six of the largest and most prestigious universities in Poland, each selected based on their comprehensive presence across major social media platforms: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube. These HEIs were chosen because they are located in the largest Polish cities, thereby ensuring a geographical spread that reflects the different and diverse communication strategies influenced by regional dynamics. Each institution is a full university with the formal rights to teach and confer doctorates, thus representing a clear benchmark for academic excellence and influence in Polish higher education.

The study analyzed Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube as, at the time of the study, they were the most widely used social media platforms globally and offer diverse modes of communication essential for effective crisis management. These platforms were selected so as to comprehensively assess how HEIs used real-time updates, visual engagement, and detailed video content to interact with various stakeholder groups during the COVID-19 crisis. A total of 5547 social media posts published by HEIs were collected. Each post also offers additional information on the interactions of the users, that is, the sum of the number of likes, reactions, shares, and comments. Although text is the dominant form of interaction, this study encompassed a diverse range of online content, including photography, infographics, and videos [

13,

16], for a full presentation of all the data published on these platforms.

Thick Big Data, a mixed-method approach [

13], was employed to perform an initial large dataset quantitative analysis. It was followed by a more thorough qualitative study. This dual approach allowed the study to maintain a positive breadth of analysis provided by a large sample of data based on the quantitative metrics of the posts that considered the pandemic, while also achieving a qualitative depth of narrative analysis of their content.

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

The data for the quantitative analysis was collected via media monitoring and capturing such details as the exact date of each post, its content, reach, and engagement metrics (number of likes, reactions, comments, and shares, with the total sum of interactions also noted). Posts were also initially coded to distinguish between COVID-19- related and non-related content based on keywords such as “COVID”, “coronavirus”, “pandemic”, “virus”, “illness”, “vaccination”, and “mask”. Posts containing these keywords were labeled as “COVID-19 related”, while all others were categorized as “non-COVID-19 related”.

Overall, 711 posts concerning the pandemic were noted and further coded and analyzed in a quantitative and qualitative manner.

Further analysis classified the COVID-19-related posts using Mergel’s (2013) [

17] framework for interpreting social media interactions, as enriched by the Górska et al. (2022) [

15] insights into how local governments use social media during crises, thus identifying the three types of communication exerted by HEIs in their official social media profiles for the posts that related to COVID-19.

Mergel (2013) [

17] introduced three SM tactics or styles of public-sector communication: (1) push (representing formal government information), (2) pull (focusing on stakeholders), and (3) a networking strategy that engages the public through the use of both tactics. The collected empirical data allowed for the distinguishing of the types of communication based on their content, language, and the tone of posts shared by HEIs, which enabled the distinguishing of the level of transparency within the communication, the internal (university) and external (stakeholders) focus, educational versus instructive communication, and the supportive (engaging) versus unsupportive tones of the messages. Building on a previous study by Górska and colleagues (2022) [

15] on how local governments utilize social media during crises, three communication types that HEIs exert in their official SM profiles for posts related to COVID-19 were then able to be distinguished. They were as follows:

Business as usual (Usual),

We are great! Just observe (Great), and

We are in this together (Together).

Applying Mergel’s typography, the “Usual” strategy is similar to Mergel’s pull, the “Great“ strategy is closer to push, and the “Together” is similar to networking. Thus, by following the focus, each social media post concerning COVID-19 could be manually coded into one of these three categories. In each of these communication strategies, other elements also existed; however, this analysis does identify the predominantly existent tone and type of content being shared on the HEIs’ social media profiles.

Qualitative Analysis

The qualitative coding scheme was based on an inductive approach, drawing on observations and analyses of the posts. All posts in the previous part that were coded as COVID-19 related were further manually coded according to the coding scheme. The qualitative component followed Saldaña’s (2013) [

43] narrative approach. A coding scheme based on a deductive approach was used, wherein observations and analysis of posts led to the initial categorization of their content, such as ‘events’, ‘education on vaccine’, and ‘functioning of HEI’. A second coding cycle identified the relationships between the initial codes and created broader categories like ‘COVID-19 education’, ‘HEI promotion’, and ‘Community support’. These broader categories were also analyzed to discern the HEIs’ rhetorical strategies. A deeper qualitative analysis then examined the language and communicative strategies employed in the posts to determine how HEIs were informing their stakeholders about the pandemic. This particular analysis utilized Excel to analyze both the content and the rhetoric, focusing on how the universities communicated their USR and crisis response initiatives.

Additional qualitative analysis then allowed for a closer analysis of the words, content, and initiatives performed by the HEIs [

44]. Emphasis was placed on the use of language and then communicative strategies to establish whether and how HEIs informed stakeholders about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Taken all together, these approaches allowed for a useful dual-layered analysis. The quantitative data provided a broad overview of communication patterns and engagement levels, while the qualitative data offered depth by revealing the content’s narrative quality and the strategic intent behind the communications.

4. Quantitative Results

The various types of SM did differ in their frequency of use by universities when communicating with stakeholders. Facebook was the most frequently used platform, totaling 45% of all posts published, followed by Twitter (31%), Instagram (15%), and YouTube (9%). Of all the communication during the first year of the pandemic, 13% were related to COVID-19, with Facebook and Twitter becoming the dominant media used to communicate about that crisis. Similar to the general SM communication pattern, COVID-19-related posts were published mainly on Facebook (53% of COVID-19-related posts) and on Twitter (31%).

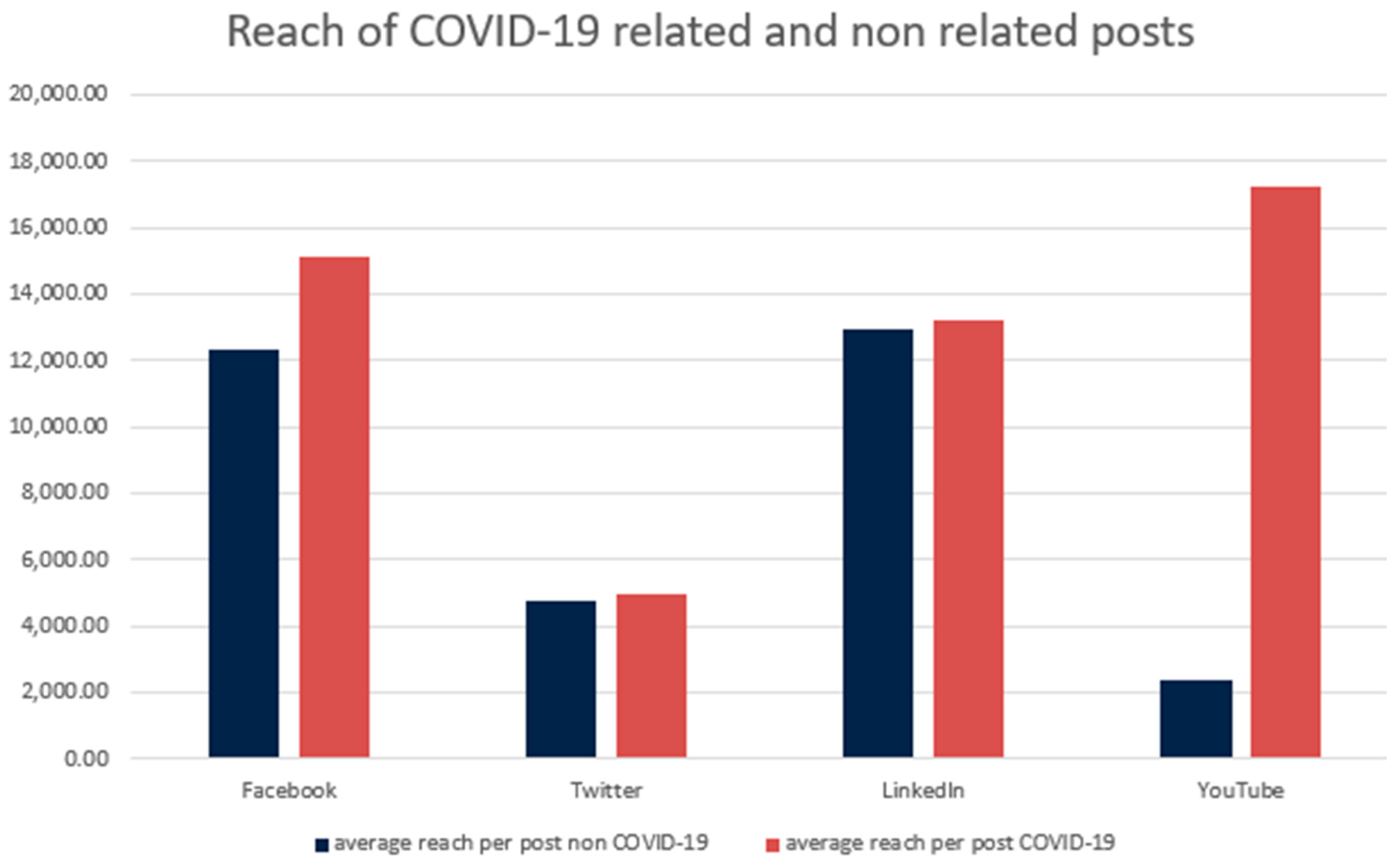

From the perspective of actual engagement, on average, the posts concerning COVID-19 had higher reach and interaction (the sum of all user activities, including likes, reactions, shares, and comments) than the non-COVID-19-related posts. COVID-19-related posts had 35% more interactions and a 23% higher reach compared to the posts not related to COVID-19.

Even when analyzing the social media platforms individually, the COVID-19-related posts had higher levels of interactions (by 34%) and reach (by 23%) in each platform (refer to

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 below).

This result suggests that during crises, users are more likely to interact with posts that specifically concern the crisis, thus leading to an increase in the reach of those posts. Further analysis here specifically considered the communication related to the crisis, and it is based on the analysis of 711 posts on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube, which included actual words connected with the crisis.

5. Qualitative Results: The Rhetorical Strategies

Based on Mergel’s (2013) [

17] and Górska et al.’s (2022) [

15] typography, the analysis below shows how the HEIs applied the three types of communication. In each of these strategies, other elements also existed; however, the analysis showcases the predominantly existent tone and type of content shared on each institution’s social media profiles. The provided examples of these posts were also anonymized.

5.1. Business as Usual

The ‘business as usual’ pandemic-related communication toward stakeholders remained formal, unengaging, and focused on the transmission of information. Their content was limited to formal statistics, official governmental policies, and changes in the functioning of universities. This type of communication did not offer engaging content, but rather focused on the transmission of information, as in, for example:

We don’t go back to university after the holidays! Remote classes extended until April 30 inclusive. #students #students # #university #covid19 #studies

Moreover, the tones of these messages were either neutral or negative. Most importantly, communication was set up only for one-way information, from the HEIs to stakeholders, without attempting to engage its observers. This type of communication included typical ‘fillers’, day-to-day content that did not hold much value for the observers and was not engaging, such as those communications referring to holidays, as in, for example:

On May 1, we celebrate Labor Day, remembering the demonstration of Chicago workers in 1886, whose aim was to fight for an eight-hour working day. 134 years after these events, the whole world is struggling with the coronavirus pandemic, and the streets are empty.

HEIs offering this type of communication informed stakeholders about daily activities, while the crisis was mentioned only for context and as background for already ongoing tasks. It seems that the HEIs continued their way and style of communication as it occurred prior to the pandemic; they were still informing stakeholders about events, with a brief annotation that, owing to restrictions, they were canceled or moved online, as in for example:

High school graduates! Every six months we saw you at the educational fair, where we told you about recruitment at our stand:The pandemic ruined the organizers’ plans, but nothing is lost! We’ll be online. #recruitment #fairs #perspectives.

Social media was also used to inform stakeholders about the initiatives being undertaken by the HEIs in response to the virus; however, these were only formal statements, without referring to the stakeholders or informing them of how they would be affected by them. This type of communication was limited to formal information that had little community-building value.

5.2. We Are Great!

Another strategy that was based on communication focused on the HEI itself and how well the HEI was managing the pandemic. The dominant tone of communication here was less formal with some visible attempts to engage the audience; however, these were focused on the institutions rather than the recipients of the message. For example:

Read about the University of X engagement in the battle against #coronavirus, one can find in the X newsletter??. Impressive work of Xuniversity to combat the pandemic. #StayAtHomeSaveLives #StrongerTogether #UniversityX.

Many of the posts concerned the formal functioning of the HEIs, but rather than informing stakeholders about the changes taking place, the tone was more to showcase how well the institutions managed the crisis to demonstrate how effectively the institutions could respond during times of crisis. This communication is formal and unengaging, informing stakeholders about the decisions, but without explaining the underlying reasons for them. In terms of community support, the communication seemed to revolve around what the HEI has already done for its stakeholders; however, there was little information included for how to obtain the necessary help. The vast amount of COVID-19 communication revolved around the HEI itself, including its events, infrastructure, and employees’ successes. Most of the communication connected with COVID-19 showed how (well) the HEI was dealing with the pandemic and how it was supporting others in doing so, as demonstrated in the following example:

Thanks to the University, the Department X and Y of (?) the Provincial Hospital in (city) received nitrile gloves, protective glasses, face shields, masks with a HEPA filter and disinfectants. We support as much as we can!

Below is another example:

Another equipment was donated by the University of X to the Naval Hospital thanks to the Faculty of Y of the University of X and the Intercollegiate Faculty of Z of the University of X.

The donated equipment will enable the launch of a complete, specialized hospital molecular diagnostics laboratory for COVID-19. Thanks to this, it will be possible to multiply the number of tests performed and diagnose patients from the Voivodeship significantly faster.

5.3. We Are Together!

The last strategy of the HEIs’ communication via SM was “Together”. This communication was directed toward stakeholders; the posts are engaging and focused on community building. The majority of the information about COVID-19 is thus intended as educational and helps the community to adjust to the new situation. Formal information about the development of the pandemic and its consequences was provided in all the strategies; however, within this type of communication, that information was provided still in the most engaging and educational manner. Instead of simply transmitting information about the restrictions, HEIs explained why the restrictions were implemented and suggested how to deal with them. An example is the following message:

Youth has its own rules, including the natural need to have a beer with your colleagues, a round of bowling or a board game match with all your flatmates. But youth is also a lesson of responsibility that your parents instilled in you in your childhood and that your university wants to reinforce at the present moment. Be aware of that we all have fallen in quite an unusual situation. According to the Ministry of Health, the risk of coronavirus is real and increasingly greater. Let’s raise to the challenge then, stay home or in dormitories, and minimize group activities Be aware! If you think there is nothing to worry about and you don’t fear the virus, remember that being infected, even without symptoms, you can pass the virus on to other people who you love, respect or like: your grandparents, parents, siblings, the lady in the dean’s office or in a copy shop…We write our theses, read books, check e-mails from our lecturers, follow posts on Facebook, clean our wardrobes… And we stay responsible for ourselves and for others!

These posts did not reveal the number of people infected by or deceased as a result of the virus; its communication was based on the principle of educating and not raising fear. The educational content was prevalent, explaining to observers how to keep their distance, wear a mask, and how to dispose of it. There was information about how to spend the day during the lockdown, along with creative ideas that could be used by stakeholders. Thus, universities were not only informing their readers about the new restrictions, but also providing alternative ways of spending their time. Similarly, as in the second group of analyzed universities, however, there was a significant amount of content connected with the university itself; thus, the focus and message had a different tone, focusing more on community building and education, as can be seen in the following example:

To keep your spirits up, the Center for Physical Education and Sports of X University has a recipe for you for some endorphins during quarantine. In the first part of our series, we invite you to:

1. Fitness training to do at home

2. Running training to be carried out outdoors (forest, park, dirt road)

Check out our training sessions here (link)

It seems that this communication was built around the stakeholders, students, and faculty members, not the university itself, as in the previously analyzed group. SM was intended to inform stakeholders about their initiatives, their history, and their problems during the pandemic. Universities used this strategy to initiate community support among the stakeholders, encouraging them to help those in need.

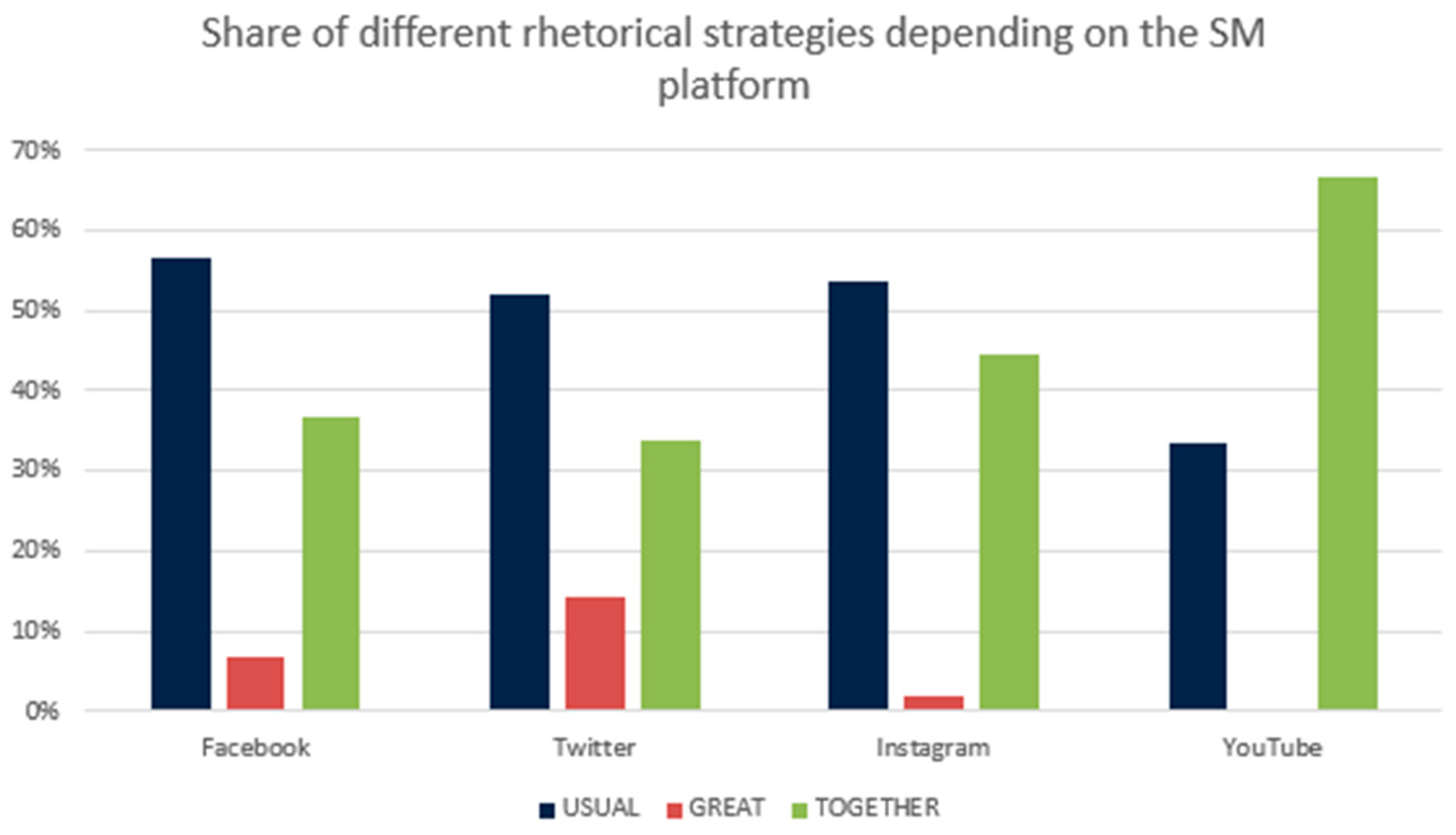

An additional quantitative analysis revealed that the “Usual” strategy predominated, accounting for 70% of all social media posts that were published, with “We are great!” being the next most frequently employed strategy for 38% of all the COVID-19- related posts.

Still, visible differences were observed among the social media platforms (see

Figure 3). For example, the strategy “

Together” was the predominant one on YouTube (67% of all COVID-19-related posts) and Instagram (54%), while “

Great” was the most popularly used on Twitter (21% of all posts), and on Facebook, the strategy of “

Usual” emerged prominently and represented 57% of that COVID-19-related content.

This analysis clearly underscores the variability in strategic communication that appeared across different social media platforms and highlights the nuanced ways that HEIs engaged with their audiences during the COVID-19 crisis.

Variations in communication strategies were also observed for the universities analyzed in this study. Notably, these differences did not correlate straightforwardly with the size of the different institutions or other readily quantifiable metrics; rather, they may indicate the specific marketing strategies used by each university.

For instance, the “Usual” strategy varied widely in its application, from 34% at one institution to 64% at another. The “Great” strategy showed even more variation, with one university employing it in 60% of their posts, while another used it in only 4% of theirs. The “Together” strategy, which emphasized community engagement, was most frequently used by one university at 59%, while another only used it at a low of 32%.

This disparity in focus suggests that while all the institutions engaged with each of the defined communication strategies to some extent, the choice and emphasis of each strategy likely reflected individual institutional priorities and marketing approaches rather than being dictated by size or other institutional metrics of each HEI. Thus, the findings highlight the importance of considering the unique cultural and strategic contexts that each university uses to operate whenever analyzing their separate social media usage.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study’s analysis of HEIs’ social media communication during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland identified key patterns and strategies that reflect the broader trends observed in crisis communication literature, particularly within the domain of higher education. The findings resonate with and extend existing crisis communication literature by demonstrating how HEIs can effectively engage diverse stakeholder groups through strategic social media use, thus contributing to a stronger theoretical understanding of crisis communication dynamics. The integration of Mergel’s (2013) [

17] classification of pull, push, and networking strategies also revealed a nuanced approach to crisis communication, which aligns with the findings from similar studies on crisis management in other sectors of society. This alignment demonstrates the scalability of HEIs’ social media strategies to other sectors, providing a foundational framework that can guide organizations in diverse fields to develop their own crisis communication strategies tailored to their unique stakeholder needs and operational contexts. The findings reveal that HEIs leverage social media platforms not just for crisis communication, but also for broader community engagement and educational outreach that resonates well with the roles outlined in the USR framework. The effectiveness of these strategies in engaging communities during the pandemic underscores their potential to be applied in other crisis situations, where maintaining stakeholder engagement and trust is crucial.

The observed prevalence of the “

Business as usual” strategy is consistent with the findings of Sörensen et al. (2023) [

23], who noted that HEIs often will default to standard communication practices and self-referential ones even during crises.

However, the significant utilization of the “

Together” strategy in these findings indicates a departure from being merely informative to delivering more supportive and community-centric communication as noted in Coelho and Figueira (2021) [

22] and O’Shea et al. (2022) [

8]. These studies emphasized the adaptive strategies that HEIs adopt in response to crisis conditions, shifting from standard operational updates to more engaging and supportive content. Although this strategy was not dominant for the current studied sample, for two universities, it was visibly a leading one. This communication was indeed aimed at bolstering community resilience and the support of some universities, further underscoring the unique role of HEIs in fostering community cohesion during global challenges. This finding also underscores a unique aspect of HEI communication that emphasizes community support and educational content consistent with the idea of USR. This finding is particularly relevant when paired with corporate crisis communication, where such community-focused strategies are less prevalent, as noted in the studies undertaken by Frandsen and Johansen (2011) [

45] and Ozanne (2020) [

46].

Coelho and Figuiera (2021) [

22] also observed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the HEIs adapted social media content strategies to these new needs. Still, within this current study, it is not possible to state clearly whether the studied HEIs’ patterns changed; however, the “

Together” rhetorical strategy was still dominating on the comparatively “new” social media platforms used by HEIs, such as YouTube and Instagram.

The differential use of social media platforms that was found in this study aligns with the findings from the broader social media strategy literature. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter were predominantly used for disseminating information quickly, while Instagram and YouTube played crucial roles in building community engagement through more visual and narrative-driven content. This platform-specific use of social media underscores the strategic deployment of digital tools to achieve varied communication objectives to enhance both reach and engagement during the pandemic.

Building on the theoretical foundations set by Mergel (2013) [

17] and further explored by Górska et al. (2022) [

15], this study extends the understanding of the role of social media in crisis communication in the higher education sector. The application of Mergel’s framework allowed for a nuanced analysis of how HEIs align their social media strategies with broader USR principles, particularly when under the pressures of a global health crisis. Moreover, it extends the principles of Mergel’s (2013) [

17] crisis communication framework within the higher education sector, providing a nuanced understanding of how traditional models are adapted to the unique dynamics and societal responsibilities of HEIs.

This analysis indicates that HEIs are not only disseminating information, but also actively working to build and maintain a sense of community and shared purpose among all their stakeholders.

The empirical insights from this study clearly contribute to the scant literature on HEIs’ use of social media during crises in Central and Eastern European regions. Unlike the existing studies that often have focused on the use of social media by individual academics or students, this study provides a comprehensive overview of institutional strategies and their effectiveness when managing communications during a crisis. The findings also suggest that HEIs are capable of leveraging social media to not only manage crisis communication effectively but also to enhance their role in delivering positive societal support and development.

This study not only highlights how HEIs use social media to manage crises but also how they can effectively incorporate sustainability into their communication strategies. By doing so, they not only address immediate challenges but also contribute to the broader goals of sustainable development, aligning with the global trends towards a more sustainable future.

6.1. Practical Implications

The practical implications of this study extend to HEIs and other organizations that leverage social media for stakeholder communication during crises. First, the findings advocate for the strategic use of social media, not only to disseminate information but also to engage stakeholders more actively during crises. By providing educational and supportive content, HEIs can foster a sense of community and solidarity, enhancing resilience during challenging times, beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, HEIs can utilize social media to enhance their USR and educate stakeholders about the use of sustainability practices during crises. This communication includes sharing information about how the crisis impacts social systems and what steps the institution and its stakeholders can take to respond well and sustainably to crises.

Second, this study highlights the importance of using a variety of social media platforms to reach different audience segments. HEIs should consider the characteristics of each platform they use, such as the type of content that is popular, the age range of the users, and the level of engagement that is most useful, when designing their communication strategy. HEIs can use these insights to tailor their messages to each platform and thereby increase the likelihood of reaching their intended audience. Part of this tailored approach should also involve disseminating content that highlights the HEIs’ commitment to sustainability, thereby showing how they are incorporating sustainable practices into their crisis responses and recovery plans.

Third, this study emphasizes the need for transparency and two-way communication between HEIs and their stakeholders. HEIs should not only provide information about their own initiatives, but also listen to the feedback and concerns of their stakeholders. Doing so can help them identify areas where they can improve their response to crises and better meet the needs of their stakeholders. Such engagement should also include discussions related to sustainability, inviting their stakeholders to contribute ideas on how the institution can enhance its sustainable practices and policies both during the crisis and after it has lapsed.

Finally, this study highlights the importance of the tone and language used in social media communication during crises. HEIs should strive to use language that is empathetic, supportive, and informative rather than language that is only negative or fear-inducing. By doing so, they can help build trust and credibility with their stakeholders, which can provide long-term increased benefits for the institution and its members.

Incorporating sustainability into the HEI communication strategy means using language that underscores the interconnectivity of social, economic, and environmental well-being, thereby reinforcing the HEIs’ role in fostering a sustainable future.

In conclusion, the practical implications of this study suggest that HEIs should view social media as an important tool for engaging with their stakeholders during crises and that they should also carefully consider the type of content, platform, and tone used in their communication strategy during difficult times. By doing so, they can build stronger relationships with their stakeholders, increase transparency, and better meet the needs of their community overall during times of crisis.

By also integrating sustainability into their social media communication strategies during crisis communication, HEIs can not only address the immediate challenges that are presented, but also contribute to the long-term resilience and sustainability of their communities and society at large.

6.2. Limitations

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study focused only on the social media communication of HEIs in Poland, and thus it may not be generalizable to other countries or types of institutions. Second, the study was limited to data collected during the first year of the pandemic and may not fully capture the evolving communication strategies and dynamics that can occur over time. Third, the study relied solely on publicly available data, which may not fully capture all aspects of the communication between HEIs and their stakeholders. Fourth, this study did not explore the impact of social media communication on stakeholders’ attitudes or behaviors. Future studies could address these limitations by including a more diverse sample of HEIs, analyzing a longer timeframe, incorporating qualitative data from stakeholders, exploring the impact of their communications on stakeholders, and investigating the differences in communication strategies across different types of HEIs.

By aligning immediate crisis communication strategies with broader societal goals, HEIs can not only respond effectively to crises but also enhance their societal leadership, preparing them to meet future challenges with resilience and strategic foresight. In conclusion, this study highlights the strategic use of social media that was used by HEIs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Its findings reflect the integration of crisis communication strategies with the broader goals of USR. The findings also underscore the importance of adaptive communication strategies that go beyond traditional informational roles to actively support and engage with communities during times of crisis. Future research could build on these insights by exploring the long-term impacts of such strategies on stakeholder relationships and institutional reputation, particularly in post-pandemic times.